A 7-month randomized crossover study of children with hypoparathyroidism demonstrates that synthetic human PTH 1–34 given twice daily by subcutaneous injection produces improved metabolic control compared to once-daily administration.

Abstract

Context: Hypoparathyroidism is among the few hormonal insufficiency states not treated with replacement of the missing hormone. Long-term conventional therapy with vitamin D and analogs may lead to nephrocalcinosis and renal insufficiency.

Objective: Our objective was to compare the response of once-daily vs. twice-daily PTH 1–34 treatment in children with hypoparathyroidism.

Setting: The study was conducted at a clinical research center.

Subjects: Fourteen children ages 4–17 yr with chronic hypoparathyroidism were studied.

Study Design: This was a randomized cross-over trial, lasting 28 wk, which compared two dose regimens, once-daily vs. twice-daily PTH1–34. Each 14-wk study arm was divided into a 2-wk inpatient dose-adjustment phase and a 12-wk outpatient phase.

Results: Mean predose serum calcium was maintained at levels just below the normal range. Repeated serum measures over a 24-h period showed that twice-daily PTH 1–34 increased serum calcium and magnesium levels more effectively than a once-daily dose. This was especially evident during the second half of the day (12–24 h). PTH 1–34 normalized mean 24-h urine calcium excretion on both treatment schedules. This was achieved with half the PTH 1–34 dose during the twice-daily regimen compared with the once-daily regimen (twice-daily, 25 ±15 μg/d vs. once-daily, 58 ± 28 μg/d; P < 0.001).

Conclusions: We conclude that a twice-daily PTH 1–34 regimen provides a more effective treatment of hypoparathyroidism compared with once-daily treatment because it reduces the variation in serum calcium levels and accomplishes this at a lower total daily PTH 1–34 dose. The results showed, as in the previous study of adult patients with hypoparathyroidism, that a twice-daily regimen produced significantly improved metabolic control compared with once-daily PTH 1–34.

Experimental synthetic human PTH 1–34 replacement therapy in adults with hypoparathyroidism maintains serum calcium in the normal range and reduces urine calcium excretion (1,2,3). This therapy, however, is not yet approved for the treatment of primary hypoparathyroidism. Unlike most hormone insufficiency states, primary hypoparathyroidism is not treated by replacing the missing hormone. Conventional therapy with 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol (calcitriol), or other vitamin D analogs, normalizes serum calcium but does not have the renal calcium-retaining effect needed to normalize urine calcium. Thus, patients with hypoparathyroidism, who are treated with vitamin D analogs, have a tendency toward hypercalciuria. Eventually, this may lead to nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis, or renal insufficiency (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14).

PTH 1–34 was first administered for the diagnosis of pseudohypoparathyroidism, which is marked by decreased urinary cAMP response to PTH administration. PTH 1–34 was then used as an experimental treatment for osteoporosis (15,16,17,18) and has recently been approved for therapeutic use in adults with this disorder. Most of the data regarding the safety and efficacy of PTH 1–34 administration in adults are from osteoporosis treatment studies. Animal toxicity studies have raised concerns regarding dose-dependent PTH effects on the bone. Long-term, supraphysiological doses of recombinant human PTH 1–34 (rhPTH), given to rats with normal functioning parathyroid glands, led to osteosarcomas in some experimental animals (19,20). This resulted in a warning against the use of PTH 1–34 in children. This heightened risk associated with rhPTH administration however, is generally viewed as particular to the rat and not relevant to PTH-deficient patients receiving physiological replacement doses.

There are few published studies on the effects of PTH 1–34 in hypoparathyroidism. In 1990, Strogmann et al. (21) described the short-term sc PTH 1–38 treatment of two children with hypoparathyroidism. In a randomized controlled trial of 10 adults lasting 20 wk, we compared conventional therapy, calcitriol and calcium, with once-daily replacement PTH 1–34 (1). We found once-daily PTH 1–34 to be superior to calcitriol in the treatment of hypoparathyroidism because it produced a significantly reduced level of urine calcium excretion and maintained mean serum calcium levels in the normal range throughout most of the day. We subsequently performed a randomized cross-over trial in 17 adults (2) comparing once-daily and twice-daily PTH 1–34 regimens, and found that twice-daily PTH 1–34 allowed a marked reduction in the total daily PTH 1–34 dose, with less fluctuation in serum calcium, normalization of urine calcium, and significantly improved metabolic control. In a subsequent long-term treatment study, 27 adults with hypoparathyroidism were randomized to either calcitriol or PTH 1–34 therapy (3). Our findings demonstrate that twice-daily PTH 1–34 administration maintains serum calcium in the low-normal or just below the normal range over a 3-yr period with concurrent normalization of urinary calcium excretion. The present study represents the first randomized controlled trial of PTH 1–34 replacement therapy in children with hypoparathyroidism. The results showed, as in the previous study of adult patients with hypoparathyroidism, that a twice-daily regimen produced significantly improved metabolic control compared with once-daily PTH 1–34 (2).

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Fourteen children ages 4–17 yr that participated in the study. All subjects (Table 1) were diagnosed with hypoparathyroidism before study entry by low levels of intact PTH during hypocalcemia (data not shown). Patients were excluded if they had severe renal insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate < 25 ml/min) or evidence of liver disease. Creatinine clearance values were corrected for body surface area (Table 1). With the exception of one patient (A) who received 1-α-hydroxycholecalciferol (1-α calcidiol), all patients were receiving calcitriol and calcium supplementation at study entry. The duration of hypoparathyroidism at study entry ranged from 1–11 yr (Table 1). The last calcitriol dose was given approximately 12 h before the initiation of PTH 1–34. At study entry, only two subjects (A and K) were receiving magnesium replacement for treatment of chronic hypomagnesemia (normal range: 0.75–1.00 mmol/liter). Three other patients had magnesium levels below the normal range during the baseline evaluation and were started on magnesium shortly after study entry. Five subjects developed low-serum magnesium levels further into the protocol while on PTH 1–34. By the end of the initial 14-wk period, seven patients were supplemented with magnesium to maintain fasting serum magnesium levels in the normal range. By the end of the study, a total of 10 subjects required magnesium supplementation (120–580 mg/d). Four patients had evidence of nephrocalcinosis by renal computed tomography scan, and three patients had renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 80 ml/min, corrected for body surface area). Patient A had a sporadic activating mutation in the calcium-sensing receptor, causing severe hypocalcemia and seizures during infancy (22). Patients B, C, and G were three brothers in a family containing seven members (five sons, father, and uncle) with hypoparathyroidism. Subjects H, I, and J were three siblings from a family with no affected parent or grandparent. Two families (subjects D and E are brothers, and K and L are brothers), with no prior history of hypoparathyroidism, each had two affected boys with autoimmune polyglandular failure syndrome type 1 (APS-1). Patient M’s father and grandmother also had hypoparathyroidism. All patients with idiopathic familial hypoparathyroidism were tested for the presence of a calcium receptor mutation. A defect was found in only one patient (A).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory features of 14 children with hypoparathyroidism at study entry

| Patientsa | Age (yr) | Sex | Diagnosis | Duration of hypoparathyroidism (yr) | Calcium mmol/liter (2.05–2.5)b | Phosphorus mmol/liter (0.8–1.6) | Magnesium mmol/liter (0.65–1.05) | Urine calcium mmol/24 h (1.25–6.25) | Creatinine clearance ml/min (90–125)c | Nephrocalcinosis CT results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | F | CaR | 5 | 2 | 2.16 | 0.55 | 3.9 | 66 | − |

| B | 11 | M | Idiopathic | 1 | 1.92 | 3.21 | 0.71 | 1.08 | 86 | − |

| C | 17 | M | Idiopathic | 3 | 2.02 | 2.26 | 0.79 | 4.01 | 112 | − |

| D | 7 | M | APS-1 | 2 | 2.22 | 1.95 | 0.77 | 7.08 | 108 | − |

| E | 13 | M | APS-1 | 1 | 2.3 | 1.78 | 0.75 | 7.00 | 98 | + |

| F | 8 | M | Postsurgical | 1 | 2.14 | 1.97 | 0.75 | 3.58 | 124 | − |

| G | 11 | M | Idiopathic | 1 | 2.12 | 2.55 | 0.88 | 3.3 | 138 | − |

| H | 4 | F | Idiopathic | 4 | 2.5 | 1.95 | 0.84 | 2.71 | 70 | + |

| I | 11 | F | Idiopathic | 11 | 1.7 | 2.91 | 0.69 | 3.91 | 66 | + |

| J | 9 | M | Idiopathic | 9 | 1.8 | 2.69 | 0.81 | 4.21 | 87 | + |

| K | 9 | M | APS-1 | 4 | 2.25 | 1.87 | 0.80 | 9.91 | 89 | − |

| L | 5 | M | APS-1 | 1 | 2.02 | 1.95 | 0.77 | 3.95 | 119 | − |

| M | 6 | M | Idiopathic | 2 | 2.0 | 2.06 | 0.89 | 3.3 | 94 | − |

| N | 11 | F | APS-1 | 8 | 2.2 | 1.88 | 0.81 | 8.54 | 110 | − |

−, Negative; +, positive; APS-1, Autoimmunepolyglandular failure type 1; CaR, calcium receptor mutation; CT, computed tomography; F, female; M, male.

Patients were receiving calcitriol and supplemental calcium at the time of these studies.

Normal range in parenthesis.

Corrected for height and weight.

Protocol

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and all subjects and their parents gave written informed consent. This was a randomized, cross-over study comparing once-daily with twice-daily PTH 1–34 therapy. Randomization to the dose schedules, once-daily or twice-daily PTH, occurred at the initial baseline study visit. The two arms, each lasting 14 wk, were divided into a 2-wk inpatient dose-adjustment phase and a 12-wk outpatient phase during which continued dose adjustment was permitted as indicated. Crossover to the opposite dose schedule arm occurred at the 14-wk time point.

After completion of baseline testing, study participants were assigned randomly to receive initially either once-daily PTH 1–34 at 0900 h or twice-daily PTH 1–34 at 0900 and 2100 h. The PTH 1–34 was administered sc in the extremities with an insulin syringe, and the initial dose was 0.7 μg/kg·d for both treatment arms. Synthetic human PTH 1–34 (purchased from Bachem Inc., Torrance, CA) was prepared at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center for human administration as previously described (1).

The dose of PTH 1–34 was adjusted in increments or decrements of approximately 15% to maintain urine calcium within the normal range. Serum calcium was maintained in the low-normal or just below the normal range to avoid an increase in urine calcium. Both serum calcium and 24-h urine calcium were measured daily during the initial 2 wk, and weekly thereafter.

Dietary intake of calcium ranged from 800 to 1500 mg elemental calcium during both the inpatient phase (based upon daily dietary calcium intake counts) and outpatient phase (based upon dietary history and results of a food frequency questionnaire). No study participant received phosphate binders, diuretics, or other study medications that affected serum calcium, magnesium, or phosphorus levels.

Study end points

The primary outcome measures were the levels of calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium in the serum and urine. These were assessed in two ways: fasting 0800-h serum calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and vitamin D levels (before the morning dose of PTH 1–34), along with the corresponding 24-h urine calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium levels, were measured six times between wk 12 and 14. The mean (±sem) of these six measurements is referred to as the 14-wk level. Second, at 14 wk, near the conclusion of each treatment arm, patients underwent blood sampling over a 24-h period to assess the time course of PTH 1–34 effects on mineral metabolism. Serum was collected at 0900 h (before the dose of PTH 1–34) representing time zero (Fig. 1) and then every 2 h until 0900 h the next morning. On the same day, urine was collected at 4-h intervals from 0900 h (before PTH 1–34) to 0900 h the next morning. Subjects consumed a diet containing at least 800 mg elemental calcium during the 24-h test.

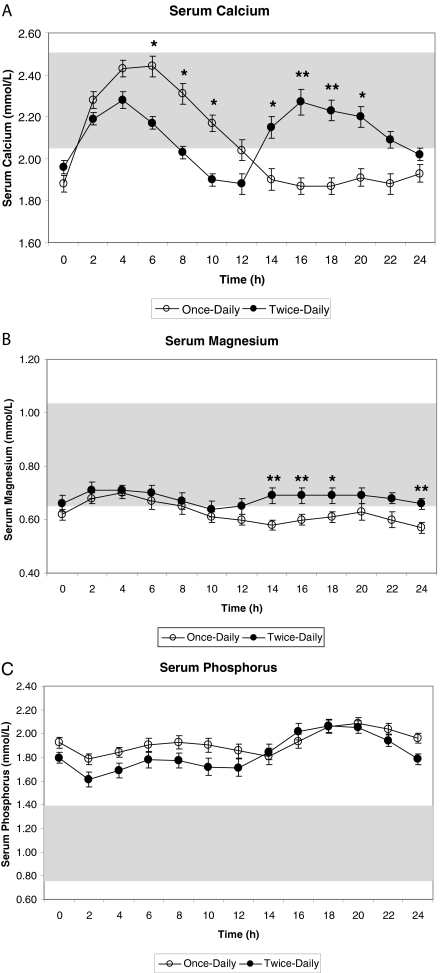

Figure 1.

Twenty-four hour profile of serum calcium (A), magnesium (B) and phosphorus (C), values (mean ± sd) obtained at 14 wk comparing once vs. twice-daily sc PTH injections given at times zero or 0 and 12 h, respectively.P < 0.05 once vs. twice-daily PTH administration.

The secondary outcome measures were the dose of PTH 1–34 administered, the serum alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin, which reflect bone formation, measured before the morning dose of PTH 1–34, and corresponding 24-h urine pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline, which reflect bone resorption. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D3 were measured at the beginning of each study arm along with the other serum measures before the morning PTH 1–34 dose.

Assays

Biochemical assays have been previously described (2). All blood and urine samples for calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, creatinine, and alkaline phosphatase were measured at the Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health. Blood samples were measured using the Hitachi 917 analyzer (Indianapolis, IN). Urine samples were measured using the Cobas-Mira analyzer (Montclair, NJ). RIAs for intact PTH 1–34, cAMP, were measured at Corning Hazleton (Vienna, Va). Vitamin D, total urine pyridinoline, and deoxypyridinoline and serum osteocalcin, were measured at Quest Diagnostics-Nichols Institute (San Juan Capistrano, CA). Total urine pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline were measured by fluorometry after reversed-phase HPLC of hydrolyzed urine.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± sd, unless otherwise stated, and were analyzed using SAS system software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant, unless the Bonferroni correction applied. For the analysis of the 24-h serum and urinary profiles, general linear models for unbalanced designs in repeated measures ANOVA were used due to the additional between- and within-factor of time points during the 24-h period of testing. Multiple post hoc comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. Logarithmic transformation was performed, where appropriate, to achieve uniformity of variance. The counts of occurrences of hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia during the 24-h period were compared using paired t tests. Sequence of treatment had an effect only on urine phosphorus measures and was adjusted for in the repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

In this study of children with hypoparathyroidism, we found that treatment with twice-daily PTH maintained mean serum calcium values in the normal range throughout the 14-wk treatment period.

Response to treatment at 14 wk

At the conclusion of the 14-wk treatment arm, the mean total daily dose on twice-daily PTH 1–34 was significantly lower compared with the once-daily regimen (total twice-daily 25 ± 15 μg/d vs. once daily 58 ± 28 μg/d; P < 0.001).

Serum calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, alkaline phosphatase, and osteocalcin mean levels obtained before the morning dose of PTH 1–34 were repeatedly measured during the final 2 wk of each treatment arm (Table 2). Twice-daily PTH 1–34 produced significantly higher mean 0800-h (predose) serum calcium levels compared with calcium levels on once-daily PTH 1–34 (2.04 ± 0.03 vs. 1.87 ± 0.03 mmol/liter; P < 0.001). Magnesium levels during twice-daily PTH 1–34 were significantly higher compared with once-daily PTH 1–34 (0.71 ± 0.02 vs. 0.66 ± 0.02 mmol/liter; P < 0.01). By contrast, the 0800-h serum phosphorus values remained elevated during both dose schedules of PTH 1–34. Markers of bone formation, alkaline phosphatase, and osteocalcin increased during PTH 1–34 therapy compared with baseline, but there was no significant difference between the two treatment arms. The serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D values were similar during both dose schedules of PTH 1–34.

Table 2.

Effect of PTH 1–34 regimen on blood and urine mineral levels, markers of bone turnover, and vitamin D levels measured at 14 wk

| Baseline calcitriol | Once-daily PTH | Twice-daily PTH | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | ||||

| Calcium (mmol/liter) | 2.09 ± 0.06 | 1.87 ± 0.03a | 2.04 ± 0.03 | 2.05–2.50 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/liter) | 2.23 ± 0.12 | 2.11 ± 0.05 | 2.08 ± 0.07 | 0.8–1.6 |

| Magnesium (mmol/liter) | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.66 ± 0.02a | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.65–1.05 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/liter) | 207 ± 20.2 | 330 ± 29.4 | 298 ± 26.4 | 100–320 |

| 25-Hydroxyvitamin D (ng/ml) | 32 ± 3.3 | 22 ± 2.5 | 27 ± 2.2 | 20–80 |

| 1,25 OH vitamin D (pg/ml) | 31 ± 2.8 | 35 ± 3.2 | 37 ± 2.6 | 15–60 |

| Osteocalcin (ng/dl) | 14 ± 2.5 | 89 ± 14.7 | 68 ± 9.3 | 1.6–9.2 |

| Urine | ||||

| Calcium (mmol/d) | 4.7 ± 0.66 | 5.0 ± 0.51 | 4.6 ± 0.60 | 1.25–6.25 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/d) | 19.3 ± 2.84 | 21.66 ± 2.38 | 22.6 ± 2.24 | 13–42 |

| Magnesium (mmol/d) | 3.9 ± 0.56 | 4.7 ± 0.44 | 4.4 ± 0.44 | 3.0–4.3 |

| Pyridinoline (nmol/mmol creatinine) | 187 ± 15.7 | 361 ± 26.2 | 346 ± 23.5 | 42–440 |

| Deoxypyridinoline (nmol/mmol creatinine) | 50 ± 4.0 | 123 ± 10.6 | 114 ± 8.7 | 17–110 |

Values are given as means ± sem. Levels associated with PTH therapy are predose values obtained at the end of a 14-wk treatment arm. Calcitriol treatment was not optimized in this study or compared with PTH therapy.

P < 0.01 vs. twice-daily PTH.

The PTH 1–34 dose schedule did not significantly affect mean 24-h urinary mineral excretion levels. Urine calcium levels were normal during both treatment arms (5.0 ± 1.9 for once-daily vs. 4.6 ± 2.2 mmol/d for twice-daily PTH 1–34). For both study arms, the mean urine phosphorus levels were within normal limits. Mean urine magnesium excretion was similar during once and twice-daily PTH 1–34. Urine pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline, markers of bone turnover, increased in response to PTH 1–34 therapy and were similar during both PTH 1–34 dose schedules.

Twenty-four hour profile of serum calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium

The 24-h profiles of serum calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium were measured at the conclusion of each 14-wk treatment phase (Fig. 1). During the initial part of the day (2–10 h time points), once-daily PTH 1–34 produced higher calcium levels but produced lower levels during the second part of the day (14–24 h time points). Specifically, mean serum calcium levels were significantly higher at the 6- to 10-h time points in the once-daily arm (2.44 ± 0.19 mmol/liter for 6 h, 2.31 ± 0.19 mmol/liter for 8 h, and 2.17 ± 0.16 mmol/liter for 10 h, P = 0.02, P = 0.03, P = 0.02, respectively; Fig. 2), whereas they were significantly lower at the 14- to 20-h time points during the second part of the day (1.90 ± 0.19 mmol/liter for 14 h,1.87 ± 0.16 mmol/liter for 16 h, 1.87 ± 0.15 mmol/liter for 18 h, and 1.91 ± 0.16 mmol/liter for 20 h, P = 0.04, P < 0.01, P < 0.01, P = 0.04, respectively; Fig. 1). The 24-h mean serum calcium levels were not significantly different overall comparing once- and twice-daily PTH 1–34 (2.07 ± 0.27 mmol/liter for once-daily vs. 2.11 ± 0.20 mmol/liter for twice-daily; P = 0.6).

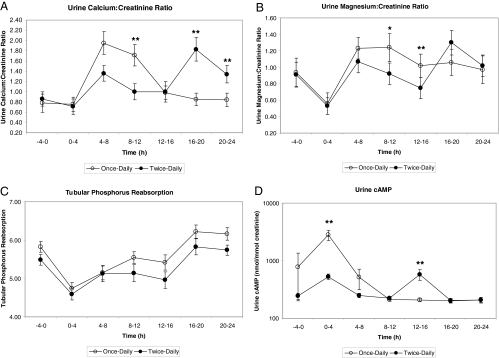

Figure 2.

Twenty-four hour profile of urine excretion of mean calcium (A), magesium (B) and phosphorus (C), and cAMP (D) values (mean ± sd) obtained at the conclusion of each study arm comparing once-daily and twice-daily PTH sc injections at times zero or 0 and 12 h, respectively.P < 0.05 once vs. twice-daily PTH administration.

Particularly during the second half of the day (12–24 h), twice-daily PTH 1–34 normalized serum calcium levels more effectively than once-daily PTH 1–34. For these children the frequency of hypocalcemia during the 24-h test was significantly less during twice-daily PTH 1–34 than during once-daily PTH 1–34 (mean count 2.1 ± 1.3 vs. 4.0 ± 2.4; P < 0.001). Twice-daily PTH 1–34 produced mean levels of hypocalcemia only during three time points (0, 10, and 12 h), whereas once-daily PTH 1–34 produced mean hypocalcemic levels at seven different time points (0, and 12–24 h) during the 24-h test.

Over the 24-h period, ANOVA demonstrated a statistically significantly higher level of serum magnesium response to twice-daily PTH 1–34 than once-daily (0.68 ± 0.10 vs. 0.62 ± 0.09; P < 0.01). For patients on once-daily therapy, magnesium levels remained subnormal during the 10- to 24-h time points. Twice-daily PTH 1–34 produced normal mean serum magnesium levels throughout the day, which were significantly higher for the 14- to 18-h and 24-h time points (0.69 ± 0.11 mmol/liter for 14, 16, and 18 h, and 0.66 ± 0.07 mmol/liter at 24 h, P = 0.003, P = 0.003, P = 0.01, P = 0.008, respectively; Fig. 1).

There were no significant differences in the serum phosphorus response to PTH 1–34 related to the number of doses of PTH 1–34 administered. In contrast to serum calcium, for which the greatest difference between the two regimens was observed during the latter portion of the day, there were no differences in nighttime phosphorus levels between the two regimens (Fig. 1). Mean 24-h serum phosphorus levels remained similar and above normal during both the twice-daily and once-daily regimens (1.92 ± 0.21 mmol/liter vs. 1.83 ± 0.26 mmol/liter; P = 0.1).

Twenty-four hour profile of urine calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and cAMP

The 24-h profiles of urine calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and cAMP were measured at the conclusion of each 14-wk treatment phase (Fig. 2). Except for tubular phosphorus reabsorption (P = 0.03), none of the mean urine profiles was statistically different by treatment over the 24-h period; however, there were differences at specific time points for some of these measures.

The mean urine calcium to creatinine ratio was significantly higher at the 8- to 12-h time point during the once-daily arm (1.71 ± 0.80 mmol/liter; P = 0.001), and significantly lower during the once-daily arm at the 16- to 20-h and 20- to 24-h time points (0.85 ± 0.47 and 0.84 ± 0.42 mmol/liter; P = 0.0007, P = 0.009, respectively). During the 8–12 and 12- to 16-h time points, once-daily PTH 1–34 produced significantly higher mean urine magnesium levels than twice-daily PTH 1–34 (1.24 ± 0.63 and 1.02 ± 0.53 mmol/liter; P = 0.03 and P = 0.001, respectively). Mean urine phosphorus levels were similar, demonstrating no significant differences in the urine phosphorus response to PTH 1–34 related to the number of doses administered. The mean urine cAMP excretion was significantly higher at the 0- to 4-h time point during the once-daily arm (2801.40 ± 2005.12 mmol/liter; P = 0.001) but lower at the 12–16 h (206.93 ± 50.83 mmol/liter; P = 0.001).

Adverse events

Adverse events were similar for both dose regimens. Subjects continued to experience occasional symptoms of neuromuscular irritability associated with serum calcium fluctuations. None of the patients experienced severe hypocalcemia or hypercalcemia requiring emergency therapy at any time during the study. There were no episodes of seizures in any of the study patients while receiving PTH 1–34 therapy. Several study patients continued to have occasional cramping, numbness, and tingling associated with transient hypocalcemia. Although conventional therapy was not compared with PTH 1–34 in this study, several patients reported an improved quality of life during PTH therapy due to fewer episodes of severe hypocalcemia. This was most apparent in the children with APS-1 who experience recurrent hypocalcemia associated with chronic intermittent malabsorption.

Discussion

We have shown, in a randomized-controlled study, the efficacy of PTH 1–34 in the treatment of hypoparathyroidism in children. These findings are consistent with our previously reported study in adults in which we demonstrated that twice-daily PTH 1–34, at a significantly lower daily dose, provides improved metabolic control compared with once-daily PTH 1–34 therapy. PTH 1–34 was well tolerated by all subjects during both treatment regimens.

The benefits of twice-daily PTH 1–34, assessed by the ability of this dose schedule to maintain normal serum calcium concentrations with simultaneous normalization of urine calcium levels, have been demonstrated here. Some fluctuation of serum calcium below the normal range still exists toward the end of the 12-h interdose interval. Hypocalcemia, however, was less frequent with twice-daily compared with once-daily PTH 1–34, and the improved maintenance of normal calcium concentrations, especially toward the end of the day, underscores the advantage of twice-daily dosing.

Further refinement of PTH administration may be provided by three times daily or perhaps by continuous delivery via patch or pump. This may also improve serum phosphorus and magnesium levels that have been suboptimal on the PTH dose regimens studied here. As in the prior study in adults, serum phosphorus levels remain elevated on PTH 1–34, and the need for magnesium supplementation appears to increase with PTH 1–34 therapy.

The increase in markers of bone turnover observed in children was similar to that observed during prior PTH 1–34 treatment studies in adults (1,2,3). Chronic elevation of bone turnover markers and the associated increase in skeletal remodeling activity may cause microscopical bone changes similar to chronic hyperparathyroidism, a disorder associated with decreased bone mineral density. Long-term studies are needed to determine if markers of bone turnover remain elevated and if anabolic effects on bone mineral density, similar to those observed with PTH treatment of osteoporotic adults (17,18,23), also apply to children with hypoparathyroidism. This is especially important in light of the warning against the use in children of rhPTH (Forteo; Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN) because of a potentially heightened risk of osteosarcoma.

PTH 1–34 is not compared with calcitriol in this study. Accordingly, it remains unknown whether PTH 1–34 is a superior treatment for hypoparathyroidism in children. Further studies to compare conventional therapy to parathyroid replacement in children are needed. Comparing two dose schedules of PTH1–34 administration, our data demonstrate that replacement therapy with twice-daily dosing is more physiological. Once-daily PTH 1–34 appeared to have diminishing effects toward the end of the day, thus producing subnormal calcium and magnesium levels. During the twice-daily arm, mean serum calcium and magnesium levels were higher during the final 10 h of the day. We conclude that a twice-daily PTH 1–34 regimen provides a more effective treatment of hypoparathyroidism compared with once-daily treatment in children because it reduces the variation in serum calcium levels at a lower total daily PTH 1–34 dose. Further studies are needed to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of twice-daily PTH 1–34 replacement in children with hypoparathyroidism.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center fellows and nursing staff for their contributions and support. We also thank nutritionist Nancy Sebring for her contributions.

Footnotes

Present address for G.B.C.: Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Indiana 46285-0520. Present address for B.S.: University of Illinois, Chicago, IL 60612-7323.

Disclosure Statement: K.K.W., N.S., D.P., and B.S. have nothing to disclose. G.B.C. is currently employed by Eli Lilly & Co.

First Published Online May 20, 2008

For editorial see page 3307

Abbreviations: APS-1, Autoimmune polyglandular failure syndrome type 1; rhPTH, recombinant human PTH 1–34.

References

- Winer KK, Yanovski JA, Cutler GB 1996 Synthetic human parathyroid hormone 1–34 vs calcitriol and calcium in the treatment of hypoparathyroidism. JAMA 276:631–636 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer KK, Yanovski JA, Sarani B, Cutler GB 1998 A randomized, cross-over trial of once-daily versus twice-daily parathyroid hormone 1–34 in treatment of hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 3480–3486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer KK, Ko CW, Reynolds J, Dowdy K, Keil M, Peterson D Gerber L, McGarvey C, Cutler GB 2003 Long-term treatment of hypoparathyroidism: a randomized controlled study comparing parathyroid hormone-(1–34) versus calcitriol and calcium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:4214–4220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JC, Young RB, Alon U, Mamunes P 1983 Hypercalcemia in children with disorders of calcium and phosphate metabolism during long-term treatment with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3. Pediatrics 72:225–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JC, Young RB, Hartenberg MA, Chinchilli VM 1985 Calcium and phosphate metabolism in children with idiopathic hypoparathyroidism or pseudohypoparathyroidism: effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Pediatr 106:421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen C, Rodbro P, Christensen MS, Hartnack B 1978 Deterioration of renal function during the treatment of chronic renal failure with 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol. Lancet 2:700–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M 1989 High-dose vitamin D therapy: indications, benefits and hazards. Int J Vitam Nutr Res Suppl 30:81–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K 1987 Calcium-regulating hormones and the kidney. Kidney Int 32:760–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz ME, Rosen JF, Smith C, DeLuca HF 1982 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-treated hypoparathyroidism: 35 patients years in 10 children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 55:727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F, Smith MJ, Chan JC 1986 Hypercalciuria associated with long-term administration of calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3). Action of hydrochlorothiazide. Am J Dis Child 140:139–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber G, Cazzuffi MA, Frisone F, de Angelis M, Pasolini D, Tomaselli V, Chiumello G 1988 Nephrocalcinosis in children and adolescents: sonographic evaluation during long-term treatment with 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. Child Nephrol Urol 9:273–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SH, Shah JH 1992 Calcinosis and metastatic calcification due to vitamin D intoxication. Horm Res 37:68–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvak J, Moldawer MP, Forbes AP, Henneman PH 1958 Hypocalcemic hypercalciuria during vitamin D and dihydrotachysterol therapy of hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 18:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer KK, Ko CW, Kopp JB 2004 Iatrogenic nephrocalcinosis and renal failure in two family members with treated hypoparathyroidism due to a calcium-sensing receptor mutation. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism 1:129–132 [Google Scholar]

- Slovik DM, Neer RM, Potts JT 1981 Short-term effects of synthetic human parathyroid hormone 1–34 administration on bone mineral metabolism in osteoporotic patients. J Clin Invest 68:1261–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovik DM, Rosenthal DI, Doppelt SH, Potts Jr JT, Daly MA, Campbell JA, Neer RM 1986 Restoration of spinal bone in osteoporotic men by treatment with parathyroid hormone 1–34 and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D. J Bone Miner Res 1:377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein JS, Kibanski A, Schaefer EH, Hornstein MD, Schiff I, Neer RM 1994 Parathyroid hormone for the prevention of bone loss induced by estrogen deficiency. N Engl J Med 331:1618–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer RM, Arnaud JR, Zanchetta R, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlk BH 2001 Effect of parathyroid hormone 1–34 on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahle JL, Long GG, Sandusky G, Westmore M, Ma YL, Sato M 2004 Bone neoplasms in F344 rats given teriparatide [rhPTH(1–34)] are dependent on duration of treatment and dose. Toxicol Pathol 32:426–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Ma YL, Hock JM, Westmore MS, Vahle J, Villanueva A, Turner CH 2002 Skeletal efficacy with parathyroid hormone in rats was not entirely beneficial with long-term treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302:304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strogmann W, Bohrn E, Woloszezuk W 1990 [Initial experiences with substitution treatment of hypoparathyroidism with synthetic human parathyroid hormone]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 138:141–146 (German) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron J, Winer KK, Yanovski J, Cunningham A, Laue L, Zimmerman D, Cutler GB 1996 Mutations in the Ca-sensing receptor gene cause autosomal dominant and sporadic hypoparathyroidism. Hum Mol Genet 5:601–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misof BM, Roschger P, Cosman F, Kurland ES, Tesch W, Messmer P, Dempster DW, Nieves J, Shane E, Fratzl P, Klaushofer K, Bilezikian J, Lindsay R 2003 Effects of intermittent parathyroid hormone administration on bone mineralization density in iliac crest biopsies from patients with osteoporosis: a paired study before and after treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:1150–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]