Abstract

Context: Despite established insulin-sensitizing and antiatherogenic preclinical effects, epidemiological investigations of adiponectin have yielded conflicting findings, and its relationship with coronary heart disease (CHD) remains uncertain.

Objective: Our objective was to investigate the relationship between adiponectin and CHD in older adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants: This was a case-control study (n = 1386) nested within the population-based Cardiovascular Health Study from 1992–2001. Controls were frequency-matched to cases by age, sex, race, subclinical cardiovascular disease, and center.

Main Outcome Measures: Incident CHD was defined as angina pectoris, percutaneous or surgical revascularization, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or CHD death. A more restrictive CHD endpoint was limited to nonfatal MI and CHD death.

Results: Adiponectin exhibited significant negative correlations with baseline adiposity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, inflammatory markers, and leptin. After controlling for matching factors, adjustment for waist to hip ratio, hypertension, smoking, alcohol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, creatinine, and leptin revealed a modestly increased risk of incident CHD with adiponectin concentrations at the upper end [odds ratio = 1.37 (quintile 5 vs. 1–4), 95% confidence interval 1.02–1.84]. This association was stronger when the outcome was limited to nonfatal MI and fatal CHD (odds ratio = 1.69, 95% confidence interval 1.23–2.32). The findings were not influenced by additional adjustment for weight change, health status, or cystatin C, nor were they abolished by adjustment for potential mediators.

Conclusions: This study shows an association between adiponectin and increased risk of first-ever CHD in older adults. Further research is needed to elucidate the basis for the concurrent beneficial and detrimental aspects of this relationship, and under what circumstances one or the other may predominate.

Higher serum adiponectin is associated with increased first coronary heart disease event risk, as shown in this nested case-control study of community-based older adults.

Since the identification of adiponectin as the most abundant factor secreted by adipocytes, the physiological role of this peptide has attracted intense scrutiny (1). Adiponectin correlates negatively with adiposity, and bears an inverse relationship with insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and inflammatory markers (2). Laboratory studies of adiponectin have demonstrated direct insulin-sensitizing actions, which accords with epidemiological evidence of a strong link between low circulating adiponectin and incident diabetes (3). These insulin-sensitizing properties suggest that reduced adiponectin concentration may underlie the heightened vascular risk associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome.

Beyond its metabolic actions, there is considerable preclinical evidence that adiponectin exerts direct antiatherosclerotic and cardioprotective effects (4). Nevertheless, epidemiological studies evaluating the role of adiponectin in cardiovascular disease have been contradictory. Among middle-aged adults, one population-based study found a significant inverse relationship with incident coronary heart disease (CHD) (5), but this has not been reproduced in subsequent investigations (6,7,8). By contrast, prospective studies of patients with heart failure (9), renal insufficiency (10), or CHD (11,12) have reported greater adverse outcomes with higher circulating adiponectin. Such increased risks have been attributed to the higher adiponectin levels associated with heart failure-related wasting (9) or impaired renal function (10), which would confound the adipokine’s proposed beneficial effects.

In older adults, population-based studies assessing CHD have been no more consistent, with findings of a race-based interaction in one (13), a significantly protective relationship in another (14), and no significant overall association in a third (15). These results contrast with those for mortality outcomes, for which an increased adiponectin-associated risk of cardiovascular and all-cause death has been independently documented (15,16), even among predominantly middle-aged cohorts (17).

It is possible that different age, sex, and race-ethnic distributions, or differences in extent of subclinical cardiovascular disease, could account for the lack of consistency in reported findings. In the present report, we investigated the association between adiponectin and CHD in a case-control study nested within a well-characterized cohort of older adults, in which we undertook matching for the aforementioned risk factors, including the preeminent predictor of incident CHD, subclinical disease (18), to minimize their potential influence on the relationship under study.

Subjects and Methods

Study population and procedures

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a population-based longitudinal survey of older adults, methods for which have been reported in detail elsewhere (19). In brief, participants consisted of noninstitutionalized, community dwelling adults aged 65–100 yr sampled from Medicare eligibility lists, and recruited from four field centers in the United States. An original cohort of 5201 individuals was recruited in 1989–1990, with a second cohort of 687 African-Americans recruited in 1992–1993, yielding a total of 5888 participants. All subjects provided written informed consent before participation.

Participants underwent extensive evaluation in 1989–1990 and again in 1992–1993. Evaluation comprised detailed history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Participants reported to CHS field centers after an 8- to 12-h fast. Blood collection, processing, and storage were conducted following quality assurance protocols (20). Laboratory measurements included serum creatinine, fasting serum glucose and insulin, lipid subfractions, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen (20,21). Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was calculated by the Friedewald equation. Cystatin C was measured in stored serum (22). Subjects were also evaluated for subclinical disease with electrocardiography, carotid ultrasound (23), measurement of ankle-brachial index (24), and Rose questionnaire for angina and claudication.

Because of limited availability of blood samples from 1989–1990, the present case-control study was nested within the 3857 participants free of prevalent cardiovascular disease who completed the 1992–1993 examination. Cases consisted of 282 men and 322 women with analyzable samples who experienced a CHD event through June 2001. Of these events, 133 and 122 were nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), 51 and 64 were fatal CHD, and the remainder nonfatal CHD, in men and women, respectively. Controls were participants free of incident CHD who were frequency matched to cases in a 1.3:1 ratio by the variables age, sex, race-ethnicity, subclinical disease status, and center.

Definitions

Diabetes was defined by a fasting glucose of more than or equal to 126 mg/dl, or by treatment with oral hypoglycemics or insulin. The homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index was also calculated (25). Meaningful weight change was defined as more than a 10-lb increase or decrease in the measured value between the 1989–1990 and 1992–1993 examinations, or based on self-report for the past year in a questionnaire that also ascertained whether such change was attributable to illness, surgery, or medication. In the latter case, weight loss was classified as “involuntary.” Subclinical disease was defined as having one or more of the following in the absence of clinical cardiovascular disease: internal carotid wall thickness more than the 80th percentile, common carotid wall thickness more than the 80th percentile, carotid stenosis more than 25%, major electrocardiogram changes (24), positive Rose questionnaire, or ankle-brachial index less than 0.9.

Cardiovascular events

Prevalent clinical cardiovascular disease was defined as MI, angina pectoris, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack. At the 1992–1993 examination, clinical cardiovascular disease was ascertained by combining the CHS questionnaire, physical examination, electrocardiography, medical record review, and physician confirmation (26).

The outcome of interest, any CHD event, is a composite of nonfatal events (MI, angina pectoris, coronary bypass surgery, or percutaneous revascularization) and fatal events (MI, sudden cardiac death, and procedure related death), as previously defined (19,26,27). A more restrictive CHD outcome was defined as nonfatal MI and fatal CHD. As detailed elsewhere (27), follow-up surveillance and ascertainment entailed interviews of participants biannually and examinations annually at each center. Potential incident events, hospitalized and outpatient, and all deaths were investigated by review of medical records and discharge summaries. These were initially classified by local physicians at the field centers, with final classification determined by a CHS committee using standardized criteria (19,27).

Measurement of adipokines

Adipokine testing was performed at the CHS Core Laboratory in 2005. Measurements made on serum stored at −70 C after venipuncture in 1992–1993 were blinded to case-control status. Adiponectin was measured using an ELISA (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation are 2.5–4.7% and 5.8–6.9%, respectively. Comparison of this assay to a RIA (LINCO Research, Inc., St. Charles, MO) revealed excellent correlation (R2 = 0.95), but higher values for the ELISA (slope = 2.19). Leptin was also measured using an ELISA. Intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation are 3.0–3.3% and 3.5–5.4%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of categorical and continuous variables between cases and controls used the χ2 and Student’s t test, respectively, whereas those of continuous variables across more than two strata applied ANOVA with linear contrasts. Age-adjusted partial correlation coefficients were computed for adiponectin and various covariates. Positively skewed variables were log transformed in all analyses.

We first investigated the relationship between adiponectin and CHD by generating sex-specific quintiles based on the distribution of adiponectin in the control group. Unconditional logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs). Adjusted models were constructed with addition of covariates capable of confounding the association between adiponectin and CHD. Covariates included the matching factors age, sex, race (Black/other), subclinical disease (yes/no), and center; the atherosclerosis risk factors waist to hip ratio, systolic blood pressure, the antihypertensive medication (yes/no), LDL-cholesterol, smoking (current vs. ever/never), alcohol consumption (none, one to six, seven to 13, ≥14 drinks per week), log creatinine, log leptin (29), and, in women, estrogen replacement (yes/no); and the potential mediators diabetes (yes/no), log high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, log triglycerides, log C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and, in individuals not receiving hypoglycemic therapy, log HOMA-IR. Additional models examined the impact of measured or self-reported weight change in the past 3- or 1-yr period, respectively, using indicator variables for weight gain and weight loss vs. stable weight, self-reported health status (poor or fair vs. good, very good, or excellent), and log-cystatin C instead of log creatinine. Tests for trend across adiponectin quintiles relied on an ordinal variable with levels corresponding to the median for each quintile. First-order tests for interaction included cross-product terms between this ordinal variable and covariates. All analyses were performed with SPSS Inc., version 12.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the study cohort. Among both men and women, cases and controls exhibited similar values for matching factors, but cases had higher body mass index, waist to hip ratio, systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, cystatin C, C-reactive protein, and leptin, as well as lower HDL-cholesterol. Male cases were more frequently on antihypertensive therapy than controls, whereas female cases had more diabetes, higher HOMA-IR, and were more often on oral hypoglycemic therapy than corresponding controls.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Men

|

Women

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 282) | Controls (n = 366) | P value | Cases (n = 322) | Controls (n = 416) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 75.5 ± 5.4 | 75.4 ± 5.4 | 0.792 | 75.3 ± 5.0 | 75.4 ± 5.1 | 0.861 |

| No. of Blacks (%) | 41 (14.5) | 58 (15.8) | 0.646 | 56 (17.4) | 78 (18.8) | 0.635 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.8 ± 3.8 | 26.2 ± 3.6 | 0.036 | 27.7 ± 5.8 | 26.7 ± 5.2 | 0.015 |

| Weight change (>10 lb) in past 3 yr | ||||||

| No. with gain (%) | 20 (8.1) | 22 (7.0) | 0.634 | 23 (8.5) | 23 (6.5) | 0.342 |

| No. with loss (%) | 28 (11.3) | 40 (12.8) | 0.604 | 32 (11.8) | 37 (10.4) | 0.586 |

| Involuntary weight loss in past year | 3 (1.1) | 10 (2.7) | 0.133 | 10 (3.1) | 6 (1.4) | 0.124 |

| Waist to hip ratio | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 140.2 ± 21.0 | 135.4 ± 22.2 | 0.006 | 140.9 ± 22.6 | 137.2 ± 21.6 | 0.024 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 75.1 ± 10.9 | 73.2 ± 11.0 | 0.031 | 71.0 ± 12.3 | 70.7 ± 11.0 | 0.801 |

| No. with hypertension treatment (%) | 130 (46.1) | 133 (36.3) | 0.012 | 165 (51.2) | 187 (45.1) | 0.096 |

| No. with diabetes mellitus (%) | 52 (18.4) | 60 (16.4) | 0.495 | 61 (18.9) | 37 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IRa,b | 2.6 (2.4–2.8) | 2.4 (2.3–2.6) | 0.117 | 2.7 (2.5–2.9) | 2.4 (2.2–2.5) | 0.004 |

| No. with oral hypoglycemic treatment (%) | 23 (8.2) | 22 (6.0) | 0.287 | 28 (8.7) | 15 (3.6) | 0.004 |

| No. with insulin treatment (%) | 8 (2.8) | 9 (2.5) | 0.765 | 10 (3.1) | 5 (1.2) | 0.070 |

| Smoking | 0.790 | 0.693 | ||||

| No. of current (%) | 30 (10.7) | 34 (9.4) | 30 (9.6) | 41 (10.0) | ||

| No. of former (%) | 168 (60.0) | 216 (59.5) | 103 (32.8) | 122 (29.8) | ||

| No. of never (%) | 82 (29.3) | 113 (31.1) | 181 (57.6) | 246 (60.1) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.506 | 0.304 | ||||

| No. with none | 133 (47.3) | 155 (42.5) | 204 (63.4) | 238 (57.2) | ||

| No. with 1–6 drinks/wk | 94 (33.5) | 128 (35.1) | 87 (27.0) | 129 (31.0) | ||

| No. with 7–13 drinks/wk | 28 (10.0) | 37 (10.1) | 14 (4.3) | 27 (6.5) | ||

| No. with ≥14 drinks/wk | 26 (9.3) | 45 (12.3) | 17 (5.3) | 22 (5.3) | ||

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 123 ± 32 | 120 ± 31 | 0.199 | 131 ± 35 | 132 ± 35 | 0.678 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl)a | 46 (45–47) | 48 (47–49) | 0.017 | 55 (54–57) | 57 (56–59) | 0.019 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl)a | 124 (117–131) | 111 (106–116) | 0.003 | 139 (132–147) | 123 (118–129) | 0.001 |

| No. with lipid-lowering treatment (%) | 13 (4.6) | 11 (3.0) | 0.284 | 20 (6.3) | 33 (8.0) | 0.377 |

| No. with estrogen replacement therapy (%) | 0 | 0 | 49 (15.2) | 57 (13.7) | 0.569 | |

| No. taking aspirin (%) | 93 (33.0) | 110 (30.1) | 0.426 | 126 (39.5) | 163 (39.5) | 0.993 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl)a | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | 1.09 (1.07–1.12) | 0.121 | 0.90 (0.88–0.93) | 0.87 (0.86–0.89) | 0.077 |

| Serum cystatin C (mg/liter)a | 1.10 (1.08–1.13) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 0.016 | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.002 |

| C-reactive protein (g/liter)a | 2.7 (2.3–3.1) | 2.0 (1.8–2.3) | 0.002 | 3.3 (2.9–3.7) | 2.5 (2.3–2.8) | 0.003 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 324 ± 65 | 318 ± 68 | 0.204 | 335 ± 70 | 327 ± 62 | 0.101 |

| Leptin (μg/liter)a | 7.4 (6.7–8.2) | 6.1 (5.6–6.6) | 0.004 | 23.5 (21.3–25.9) | 19.9 (18.3–21.7) | 0.012 |

| No. with fair or poor health status (%) | 51 (18.1) | 60 (16.4) | 0.571 | 64 (19.9) | 80 (19.3) | 0.823 |

| No. from each center (%) | 0.998 | 0.999 | ||||

| Bowman Gray | 57 (20.2) | 76 (20.8) | 80 (24.8) | 104 (25.0) | ||

| Davis | 86 (30.5) | 110 (30.1) | 89 (27.6) | 113 (27.2) | ||

| Hagerstown | 60 (21.3) | 77 (21.0) | 76 (23.6) | 98 (23.6) | ||

| Pittsburgh | 79 (28.0) | 103 (28.1) | 77 (23.9) | 101 (24.3) | ||

| No. with subclinical disease (%) | 233 (82.6) | 298 (81.4) | 0.693 | 234 (72.7) | 304 (73.1) | 0.902 |

| Adiponectin (mg/liter)a | 12.6 (11.5–13.8) | 12.4 (11.4–13.5) | 0.833 | 18.5 (17.0–20.1) | 20.3 (18.9–21.7) | 0.100 |

Geometric mean (95% CI).

Among participants not receiving insulin or oral hypoglycemic therapy.

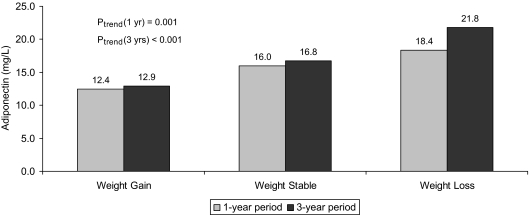

Serum adiponectin concentration did not differ significantly among participants with and without baseline subclinical cardiovascular disease [geometric mean (95% confidence interval (CI)), 15.5 (14.8–16.3) vs. 16.9 mg/liter (15.5–18.5); P = 0.623]. Levels of adiponectin showed significant age-adjusted negative correlations in both sexes with body mass index, waist to hip ratio, triglycerides, HOMA-IR, C-reactive protein, and leptin, though relations with adiposity, insulin resistance, inflammatory markers, and leptin were stronger in women than men (Table 2). Significant positive correlations were observed with HDL-cholesterol and alcohol in both men and women, whereas negative correlations with kidney function were significant only for serum creatinine in men and cystatin C in women. In turn, self-reported weight status in comparison to the prior year, and change in measured weight compared with the baseline examination 3 yr previously, manifested the expected relations with serum adiponectin. As shown in Fig. 1, the concentration of adiponectin increased progressively from individuals who experienced weight gain to those whose weight remained unchanged to those losing weight during these periods. Self-reported involuntary weight loss was not associated with significantly higher adiponectin than voluntary weight loss [21.2 (14.9–30.1) vs. 17.3 mg/liter (14.4–20.8); P = 0.278], regardless of adjustment for body mass index.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted correlations of adiponectin

| Risk factor | Men

|

Women

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | r | P value | |

| Body mass index | −0.285 | <0.001 | −0.416 | <0.001 |

| Waist to hip ratio | −0.235 | <0.001 | −0.348 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | −0.030 | 0.443 | −0.060 | 0.104 |

| Total cholesterola | −0.065 | 0.107 | −0.022 | 0.559 |

| LDL-cholesterola | −0.072 | 0.075 | −0.069 | 0.075 |

| HDL-cholesterola | 0.356 | <0.001 | 0.382 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceridesa | −0.363 | <0.001 | −0.326 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IRb | −0.359 | <0.001 | −0.465 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.131 | 0.001 | 0.145 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine | −0.115 | 0.003 | −0.039 | 0.294 |

| Cystatin C | −0.027 | 0.489 | −0.080 | 0.029 |

| C-reactive protein | −0.144 | <0.001 | −0.266 | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen | −0.021 | 0.603 | −0.207 | <0.001 |

| Leptin | −0.219 | <0.001 | −0.348 | <0.001 |

| Health status | −0.001 | 0.985 | −0.053 | 0.149 |

Individuals receiving lipid-lowering therapy excluded.

Individuals receiving glucose-lowering therapy excluded.

Figure 1.

Relationship between weight stability or change (>10 lb) and adiponectin concentration, based on measured weights 3 yr apart or self-reported weight change in the past year.

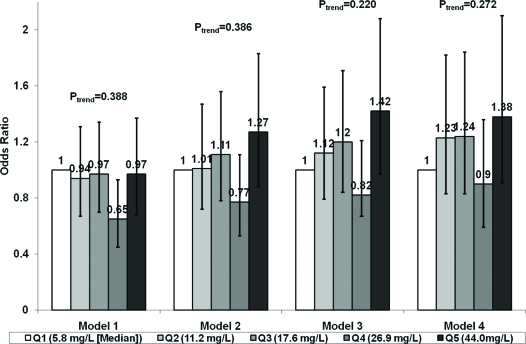

The relation between sex-specific quintiles of adiponectin and incident CHD during a mean follow-up of 7.4 yr is shown in Fig. 2. There was no significant relationship across increasing quintiles of adiponectin concentration adjusted for matching factors, though the fourth quintile was associated with a lower risk of CHD than the referent quintile. Adjustment for potential clinical and laboratory confounders, including leptin, led the relationship for the fourth quintile to disappear and point estimates for the remaining quintiles to change direction but yielded no significant overall relationship. Although the effect estimate for adiponectin levels in the upper vs. referent quintile showed a modest risk increase, this did not meet significance (model 3: OR = 1.42, 95% CI 0.97–2.08; P = 0.076). However, there was a significantly increased risk of CHD when participants in the upper quintile were compared with those in the bottom four quintiles (model 3: OR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.02–1.84; P = 0.034). Additional adjustment for weight loss, health status, or use of serum cystatin C instead of creatinine had no meaningful influence on these effect estimates.

Figure 2.

Sex-specific quintiles (Qs) of adiponectin and risk of CHD events. Model 1 contains age, sex, race, subclinical disease, and clinic. Model 2 includes covariates in model 1 plus waist to hip ratio. Model 3 shows covariates in model 2 plus systolic blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, current smoking, alcohol consumption, serum creatinine, and leptin. Model 4 contains covariates in model 3 plus health status and measured weight loss or gain more than 10 lb in past 3 yr.

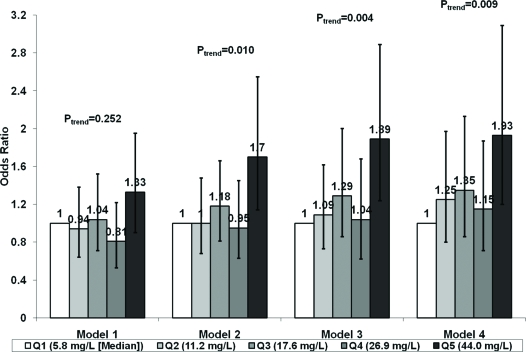

The relation of sex-specific adiponectin quintiles was then restricted to incident nonfatal MI and fatal CHD (Fig. 3). There was again no significant relationship of adiponectin quintiles adjusted for matching factors. However, adjustment for potential confounders revealed a significant association for the highest compared with the referent quintile, which was principally driven by waist to hip ratio (model 2). This relationship was not affected by adjustment for weight change, health status, or cystatin C. Although a significant linear trend was detected in these instances (Fig. 3), with a significant association for continuous adiponectin (model 3, OR per sd log increase = 1.19, 95% CI 1.02–1.38), the relationship was more consistent with a concentration of risk in the highest quintile. Comparison of the upper quintile to the bottom four quintiles after adjustment for potential confounders, including leptin, showed a significant association with nonfatal MI and fatal CHD (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.23–2.32; P = 0.001). Similar associations were observed when nonfatal MI (OR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.00–2.65) and fatal CHD (OR = 1.81, 95% CI 0.94–3.48) were considered separately.

Figure 3.

Sex-specific quintiles (Qs) of adiponectin and risk of nonfatal MI and fatal CHD. Models are as in Fig. 2.

Replacing waist to hip ratio by body mass index in these analyses did not meaningfully alter the results, nor did use of self-reported weight status or involuntary weight loss. Nor were the findings influenced by additional adjustment for antihypertensive or aspirin therapy, estrogen replacement, or substitution of cystatin C for creatinine. Restricting the analyses to individuals with normal or increased body mass index did not affect the findings. Assessment for effect modification of adiponectin by sex, race, adiposity, diabetes, subclinical disease, and other covariates failed to reveal statistically significant multiplicative interactions (P > 0.20).

Of note, adjustment for proposed mediators such as diabetes, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, C-reactive protein, and fibrinogen led to a significant relation for the highest vs. the lowest quintile of adiponectin and CHD events (OR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.1.6–2.68). In the case of nonfatal MI and fatal CHD, the relationship became stronger [OR (quintile 5 vs. 1) = 2.19, 1.37–3.48]. Similar results were obtained for either endpoint upon adjustment for HOMA-IR. However, because adjustment for potential mediators can lead to biased estimates of effect (28), these findings are not considered for hypothesis-testing purposes.

Discussion

In this case-control study nested within a community based cohort of older adults, increased adiponectin levels did not exhibit a significant protective relationship with future risk of CHD. Instead, there was an increased adjusted risk of CHD associated with the highest quintile of adiponectin, an association that became stronger when the focus was on the more stringent outcome of nonfatal MI and fatal CHD.

The present findings come in the setting of disparate epidemiological observations, which in older adults have been characterized by conflicting results with regard to CHD events and all-cause mortality. In a study evaluating the relationship of adiponectin with CHD among older Americans of both sexes, there was a significant interaction by race (13). After adjustment for confounders and mediators, an initially significant inverse relationship in whites became nonsignificant, whereas in Blacks the association was found to be direct and statistically significant. Another U.S. study found a significant protective relationship between adiponectin and nonfatal incident CHD only in men, but no significant overall relationship with incident CHD. However, there was an increased adjusted risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality with higher adiponectin concentration (15). By contrast, a study of older Swedish men did find adiponectin to be associated with a significant reduction in overall CHD risk (14). Most recently, an investigation in older British men confirmed an increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality with higher adiponectin (16), regardless of heart failure status, self-reported weight loss, and renal function (16).

Our findings, which are based on the largest number of first-incident CHD events in an elderly cohort to date, are at odds with prior reports of a protective association with CHD, whether overall (14) or limited to nonfatal events (15). They also contrast with previous null results regarding fatal and nonfatal CHD (13,15), while failing to confirm a previously noted interaction by race (13).

That the association emerged only after adjustment for covariates, principally waist to hip ratio (or body mass index), points to confounding by measures of adiposity in our sample. Because such measures were negatively correlated with adiponectin but positively correlated with an adverse metabolic profile, the greater adiposity in cases than controls effectively masked the association between adiponectin and higher CHD risk. Notably, this relationship persisted after adjustment for other factors that can influence the adiponectin-CHD relationship, especially in the elderly, including measured weight change, self-reported health status, and different measures of renal function. Thus, the findings provide compelling evidence that previously reported (15,16) direct associations of increasing adiponectin with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the elderly extend to coronary events in particular.

How does one reconcile the metabolic and vascular benefits of adiponectin documented in laboratory studies, and the protection mainly in middle-aged populations against incident diabetes and, potentially, CHD events, with the heightened risk of CHD or mortality in older adults observed here or reported elsewhere? One potential explanation is provided by the loss of fat-free mass that characterizes aging (30). Such wasting of skeletal muscle or “sarcopenia” is a recognized determinant of mortality in older adults (31). Therefore, the usual inverse relationship between adiponectin and body weight, which in younger adults is predominantly determined by changes in diet and lifestyle, can in older adults reflect frailty and physical decline, thereby confounding the adiponectin association with outcome. Nevertheless, the increased risk of CHD observed for adiponectin in this study was not modified by antecedent weight change, nor was there an appreciable influence of self-reported health status, suggesting that physical decline does not account, at least in a major measurable way, for the results.

Another consideration would be the phenomenon of “adiponectin resistance,” which has been advanced to explain paradoxical increases in adiponectin-associated adverse outcomes (32). Yet the magnitude of baseline correlations with insulin sensitivity and inflammatory markers observed here argues against this possibility. An alternative proposition is that adiponectin is produced in response to vascular inflammation to counter the atherosclerotic process (33). According to this premise, the adipokine would serve as a marker of disease severity in patients with clinical CHD or older adults with subclinical cardiovascular disease, but not to the same degree in younger populations free of prevalent CHD. However, we did not find adiponectin concentration to be higher in participants with than without subclinical disease at baseline or evidence of a significant interaction by subclinical disease status. This leaves the possibility that, in addition to its salutary actions, adiponectin has direct harmful effects, which could be more operative in the elderly. Indeed, adiponectin has increased energy expenditure through direct actions in the central nervous system in mice (34), an effect that, if present in humans, could be particularly deleterious in older adults by potentially accelerating sarcopenia.

It bears noting that adiponectin circulates in human plasma as covalently bound multimers of various molecular weights (3). Molecular signaling properties differ among adiponectin multimers, and it is the high-molecular weight (HMW) isoform that appears to be the most potent activator of insulin-sensitizing (3) and antiatherogenic (35) pathways. This raises the possibility that the heterogeneous epidemiological findings reported thus far for total adiponectin could relate to different proportions of HMW adiponectin. In keeping with this premise, some (36,37), but not all (38), clinical studies have reported stronger inverse associations for HMW than total adiponectin with insulin resistance and CHD. Interestingly, the reverse was documented in patients with heart failure, in whom total adiponectin was the stronger predictor of adverse outcome (39).

Several limitations deserve mention. Only individuals surviving until the 1992–1993 examination free of cardiovascular disease were included in the study sample. Yet because survivorship would apply equally to cases and controls, this would influence the external validity of the findings, but not their internal validity. Second, the present study did not have concurrent measures of body composition and was unable to assess directly the fraction of fat-free mass (sarcopenia) present at baseline. Future studies of older adults will need to examine the extent to which body composition influences adiponectin-related outcomes. Finally, we did not measure the HMW adiponectin isoform (37), further assessment of which will be necessary to elucidate the clinical effects of this peptide.

In conclusion, this study shows that, despite documented preclinical cardiometabolic benefits and favorable cross-sectional clinical associations, elevated concentrations of circulating adiponectin are associated with a significantly increased risk of incident CHD in older adults. These findings suggest that adiponectin harbors both salutary and harmful properties, the understanding of which could be advanced by additional attention to the adipokine’s complex multimer distribution and, in the elderly, the potential role of altered body composition.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Clinically Applied Research Grant from the American Heart Association’s Heritage Affiliate and by Grant K23 HL070854 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (to J.R.K.), and by contracts N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, and U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

A full list of participating Cardiovascular Health Study investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

First Published Online July 1, 2008

For editorial see page 3299

Abbreviations: CHD, Coronary heart disease; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CI, confidence interval; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HMW, high-molecular weight; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio.

References

- Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I 2004 Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24:29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley AJ, Bowden D, Wagenknecht LE, Balasubramanyam A, Langfeld C, Saad MF, Rotter JI, Guo X, Chen YD, Bryer-Ash M, Norris JM, Haffner SM 2007 Associations of adiponectin with body fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic Hispanics and African-Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2665–2671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K 2006 Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest 116:1784–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins TA, Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K 2007 Adiponectin actions in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Res 74:11–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pischon T, Girman CJ, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Hu FB, Rimm EB 2004 Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA 291:1730–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RS, Resnick HE, Zhu J, Tun ML, Howard BV, Zhang Y, Yeh J, Best LG 2005 Adiponectin and coronary heart disease: the Strong Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:e15–e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S, Thompson C, Sattar N 2005 Plasma adiponectin levels are associated with insulin resistance, but do not predict future risk of coronary heart disease in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5677–5683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattar N, Wannamethee G, Sarwar N, Tchernova J, Cherry L, Wallace AM, Danesh J, Whincup PH 2006 Adiponectin and coronary heart disease. A prospective study and meta-analysis. Circulation 114:623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistorp C, Faber J, Galatius S, Gustafsson F, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Hildebrandt P 2005 Plasma adiponectin, body mass index, and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 112:1756–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, Li L, Wang X, Greene T, Balakrishnan V, Madero M, Pereira AA, Beck GJ, Kusek JW, Collins AJ, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ 2006 Adiponectin and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:2599–2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilz S, Mangge H, Wellnitz B, Seelhorst U, Winkelmann BR, Tiran B, Boehm BO, Marz W 2006 Adiponectin and mortality in patients undergoing coronary angiography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4277–4286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavusoglu E, Ruwende C, Chopra V, Yanamadala S, Eng C, Clark LT, Pinsky DJ, Marmur JD 2006 Adiponectin is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, and myocardial infarction in patients presenting with chest pain. Eur Heart J 27:2300–2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya AM, Wassel Fyr C, Vittinghoff E, Havel PJ, Cesari M, Nicklas B, Harris T, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Cummings SR 2006 Serum adiponectin and coronary heart disease risk in older Black and white Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:5044–5050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frystyk J, Berne C, Berglund L, Jensevik K, Flyvbjerg A, Zethelius B 2007 Serum adiponectin is a predictor of coronary heart disease: a population-based 10-year follow-up study in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E, May S, Langenberg C 2007 Association of adiponectin with coronary heart disease and mortality: the Rancho Bernardo study. Am J Epidemiol 165:164–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH, Lennon L, Sattar N 2007 Circulating adiponectin levels and mortality in elderly men with and without cardiovascular disease and heart failure. Arch Intern Med 167:1510–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker JM, Funahashi T, Nijpels G, Pilz S, Stehouwer CD, Snijder MB, Bouter LM, Matsuzawa Y, Shimomura I, Heine RJ 2008 Prognostic value of adiponectin for cardiovascular disease and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1489–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuller LH, Shemanski L, Psaty BM, Borhani NO, Gardin J, Haan MN, O'Leary DH, Savage PJ, Tell GS, Tracy R 1995 Subclinical disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Circulation 92:720–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, O'Leary DH, Psaty B, Rautaharju P, Tracy RP, Weiler PG 1991 The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol 1:263–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman M, Cornell ES, Howard PR, Bovill EG, Tracy RP 1995 Laboratory methods and quality assurance in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Clin Chem 41:264–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP 1997 Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clin Chem 43:52–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Fried LF, Seliger SL, Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen C 2005 Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med 352:2049–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Wolfson Jr SK, Bond MG, Bommer W, Sheth S, Psaty BM, Sharrett AR, Manolio TA 1991 Use of sonography to evaluate carotid atherosclerosis in the elderly. The Cardiovascular Health Study. CHS Collaborative Research Group. Stroke 22:1155–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furberg CD, Manolio TA, Psaty BM, Bild DE, Borhani NO, Newman A, Tabatznik B, Rautaharju PM 1992 Major electrocardiographic abnormalities in persons aged 65 years and older (the Cardiovascular Health Study). Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Am J Cardiol 69:1329–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC 1985 Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, Burke GL, Kittner SJ, Mittelmark M, Price TR, Rautaharju PM, Robbins J 1995 Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 5:270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Crowley PM, Cruise RG, Theroux S 1995 Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 5:278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YK, West R, Ellison GT, Gilthorpe MS 2005 Why evidence for the fetal origins of adult disease might be a statistical artifact: the “reversal paradox” for the relation between birth weight and blood pressure in later life. Am J Epidemiol 161:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AM, McMahon AD, Packard CJ, Kelly A, Shepherd J, Gaw A, Sattar N 2001 Plasma leptin and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS). Circulation 104:3052–3056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner RN, Stauber PM, McHugh D, Koehler KM, Garry PJ 1995 Cross-sectional age differences in body composition in persons 60+ years of age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 50:M307–M316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubenoff R, Parise H, Payette HA, Abad LW, D'Agostino R, Jacques PF, Wilson PW, Dinarello CA, Harris TB 2003 Cytokines, insulin-like growth factor 1, sarcopenia, and mortality in very old community-dwelling men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Med 115:429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teoh H, Strauss MH, Szmitko PE, Verma S 2006 Adiponectin and myocardial infarction: a paradox or a paradigm? Eur Heart J 27:2266–2268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann W, Herder C 2007 Adiponectin and cardiovascular mortality: evidence for “reverse epidemiology.” Horm Metab Res 39:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Takahashi N, Hileman SM, Patel HR, Berg AH, Pajvani UB, Scherer PE, Ahima RS 2004 Adiponectin acts in the brain to decrease body weight. Nat Med 10:524–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao TS, Murrey HE, Hug C, Lee DH, Lodish HF 2002 Oligomerization state-dependent activation of NF-κ B signaling pathway by adipocyte complement-related protein of 30 kDa (Acrp30). J Biol Chem 277:29359–29362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Castro C, Luo N, Wallace P, Klein RL, Garvey WT 2006 Adiponectin multimeric complexes and the metabolic syndrome trait cluster. Diabetes 55:249–259 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y, Yamamoto R, Wakabayashi S, Uchida T, Takayanagi K, Takebayashi K, Okuno T, Inoue T, Node K, Tobe T, Inukai T, Nakano Y 2006 Comparison of serum high-molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin with total adiponectin concentrations in type 2 diabetic patients with coronary artery disease using a novel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect HMW adiponectin. Diabetes 55:1954–1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattar N, Watt P, Cherry L, Ebrahim S, Smith GD, Lawlor DA 2008 High molecular weight adiponectin is not associated with incident coronary heart disease in older women: a nested prospective case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1846–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutamoto T, Tanaka T, Sakai H, Ishikawa C, Fujii M, Yamamoto T, Horie M 2007 Total and high molecular weight adiponectin, haemodynamics, and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 28:1723–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]