Abstract

Background and purpose:

Recent studies have shown that resveratrol increased endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) numbers and functional activity. However, the mechanisms remain to be determined. Previous studies have demonstrated that increased EPC numbers and activity were associated with the inhibition of EPC senescence, which involves activation of telomerase. Therefore, we investigated whether resveratrol inhibits the onset of EPC senescence through telomerase activation, leading to potentiation of cellular activity.

Experimental approach:

After prolonged in vitro cultivation, EPCs were incubated with or without resveratrol. The senescence of EPCs were determined by acidic β-galactosidase staining. The bromo-deoxyuridine incorporation assay or a modified Boyden chamber assay were employed to assess proliferative or migratory capacity, respectively. To further examine the underlying mechanisms of these effects, we measured telomerase activity and the phosphorylation of Akt by western blotting.

Key results:

Resveratrol dose dependently prevented the onset of EPCs senescence and increased the proliferation and migration of EPCs. The effect of resveratrol on senescence could not be abolished by eNOS inhibitor or by an oestrogenic receptor antagonist. Resveratrol significantly increased telomerase activity and Akt phosphorylation. Pre-treatment with the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, significantly attenuated resveratrol-induced telomerase activity.

Conclusions and implications:

Resveratrol delayed the onset of EPC senescence and this effect was accompanied by activation of telomerase through the PI3K-Akt signalling pathway. The inhibition of EPCs senescence by resveratrol might protect EPCs against dysfunction induced by pathological factors in vivo and improve EPC functional activities in a way that may be important for cell therapy.

Keywords: resveratrol, endothelial progenitor cells, senescence, telomerase, Akt

Introduction

Despite accumulating evidence demonstrating that endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are important in the maintenance of the endothelium, being implicated in both re-endothelialization and neovascularization (Asahara et al., 1997; Takahashi et al., 1999; Kawamoto et al., 2001; Kocher et al., 2001; Walter et al., 2002; Hill et al., 2003), EPCs appear to be very susceptible to the impairment caused by cardiovascular pathogenic factors, such as oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) (Imanishi et al., 2004), homocystine (Chen et al., 2004) and angiotensin-II (Imanishi et al., 2005a). Moreover, the decrease and dysfunction of EPCs has been observed in patients with coronary arterial disease (CAD), hypertension and diabetes (Vasa et al., 2001). On the other hand, ex vivo culture of primary cells leads to cellular aging (senescence), thereby severely limiting the proliferative and migratory capacity that is useful for cell therapy of ischaemic disease. So the positive modulation of EPC levels is of particular clinical interest.

Resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene), a polyphenol phytoalexin, possesses diverse biochemical and physiological actions, including cardioprotective (Ray et al., 1999; Orallo et al., 2002), oestrogenic (Gehm et al., 1997; Klinge et al., 2003), antiplatelet (Pace-Asciak et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2002) and anti-inflammatory properties (Pendurthi et al., 1999; Shigematsu et al., 2003). The richest source of resveratrol is the root of Polygonum cuspidatum, mainly cultivated in China and Japan. The skins of grapes contain about 50–100 mg g−1 resveratrol, and this is believed to be responsible for the cardioprotective properties of red wine (Orallo et al., 2002), which contains 0.2–7 mg L−1 of wine. Recently, a few studies have documented that resveratrol dose and time dependently increased EPC numbers and enhanced cell proliferation, migration, adhesion, and their in vitro vasculogenic capacity (Gu et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007a; Balestrieri et al., 2008). However, the precise mechanisms by which resveratrol increased EPC numbers and activity remain to be determined.

Studies have demonstrated that EPC senescence was associated with EPC numbers and activity (Assmus et al., 2003; Imanishi et al., 2004). Cellular aging or senescence is characterized by cell-cycle arrest and can be triggered by different pathways (Greider, 1990). Loss of telomerase activity has been suggested to constitute the molecular clock that triggers cellular senescence (Xu et al., 2000). Murasawa et al. (2002) have demonstrated that overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery could result in a delay of senescence and a recovery or enhancement of the regenerative properties of EPCs. Furthermore, oxLDL has been shown to accelerate the senescence of EPCs by the inactivation of telomerase (Imanishi et al., 2004).

On the basis of these considerations, we investigated whether resveratrol would prevent the onset of EPC senescence through telomerase activation, leading to potentiation of cellular activity. In the present study, we have demonstrated that resveratrol prevented the onset of EPC senescence, leading to potentiation of cellular activity. Moreover, resveratrol significantly increased telomerase activity and the phosphorylation of the serine-threonine kinase, Akt.

Materials and methods

Isolation, cultivation and characterization of circulating EPCs

Informed consent was obtained from all volunteers and all the procedures were performed in accordance with national and international laws and policies. EPCs were isolated, cultured and characterized according to previously described techniques (Vasa et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2004; Seeger et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007b). Briefly, mononuclear cells (MNCs) were obtained from healthy human volunteers; all six volunteers (three male and three female; ages from 24 to 33 years with a median of 28 years) had no risk factors for CAD, including hypertension, diabetes, smoking, a positive family history of premature CAD and hypercholesterolemia and were free of wounds, ulcers, retinopathy, recent surgery, inflammation, malignant diseases or medications that might influence EPCs kinetics. MNCs were isolated from peripheral blood by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and cultured on fibronectin-coated dishes in Medium 199 supplemented with 20% foetal-calf serum and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, 50 ng mL−1). After 4 days of culture, non-adherent cells were removed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), new medium was applied and the culture was maintained through 7 days. EPCs were characterized as adherent cells double positive for dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine (DiI)-labelled acetylated low-density lipoprotein (acLDL) uptake and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled Ulex europaeus agglutinin (UEA-1) binding under a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM). They were further documented by demonstrating the expression of VE-cadherin, VEGF receptor-2 (KDR/Flt-1), CD34, AC133 (also named CD133) and CD45 by flow cytometry.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity assay

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity was measured with a β-galactosidase staining kit (BioVision, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The protocol was conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, EPCs at day 7 were treated with different concentration of resveratrol (10, 25 or 50 μM) separately for 3 more days. Then EPCs were washed in PBS, fixed for 10–15 min at room temperature with 0.5 mL of fixative solution, washed and incubated overnight at 37°C with the staining solution mix. Cells were observed under a microscope for development of blue colour (total magnification × 200) (Assmus et al., 2003; Imanishi et al., 2004).

EPC proliferation assay

EPC proliferation was assessed from the incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU). Briefly, isolated EPCs at day 10 were incubated in 96-well plastic plates (1 × 104 cells per well) with BrdU (10 μM) for another 18 h. Subsequently, the cells were fixed and BrdU incorporation was determined with a Cell Proliferation ELISA Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

EPC migration assay

Migration of EPCs was evaluated using a modified Boyden chamber assay as previously described (Vasa et al., 2001). Briefly, 5 × 104 EPCs were placed in the upper chamber of a modified Boyden chamber (Qiling Medical Equipment Factory, Jiangsu, China). VEGF (50 ng mL−1) in serum-free M199 was placed in the lower compartment of the chamber. After 24 h incubation at 37°, the lower side of the filter was washed with PBS and fixed with 2% paraformaldeyde. For quantification, cells were stained with Giemsa solution. Cells migrating into the lower chamber were counted manually in three random microscopic ( × 200) fields.

Telomeric repeat-amplification protocol assay

To investigate the effect of resveratrol on telomerase activity, EPCs at day 7 were treated with different concentration of resveratrol (10, 25 or 50 μM) for 24 h, with or without pre-treatment with LY294002 (10 μM). For quantitative analyses of telomerase activity, the telomeric repeat-amplification protocol assay, in which the telomerase reaction product is amplified by PCR (Kim and Wu, 1997) was performed using the TeloTAGGG PCR ELISAPLUS kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

The EPCs were treated with various concentrations of resveratrol for 24 h. They were then washed twice with PBS and lysed in ice-cold HNTG buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% glycerol). The lysates were centrifuged at 12 000 g (4 °C) for 20 min, and the protein concentrations of the supernatants were determined using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) protein assay. Equal amounts of proteins (50 mg) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels, as described previously (Benndorf et al., 2003). After the separation, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). Membranes were blocked by incubation in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.5) containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and 5% (v/v) nonfat dry milk for 2 h, followed by 2 h of incubation at room temperature with rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Akt-Ser473 or anti-Akt antibodies. The filters were washed extensively in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 before incubation for 1 h with a secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Membranes were then washed and developed using the EZ-ECL Detection Kit (Biological Industries, Ashrat, Haifa, Israel).

Annexin-V-propidium iodide-binding assay

To determine whether or not resveratrol, over the range of concentrations studied, affected the apoptosis of EPCs, the apoptotic rate of EPCs was detected by the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (BioVision) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, after incubation with resveratrol of different concentrations separately for 3 days, 5 × 106 isolated EPCs were resuspended in 500-μL-binding buffer. FITC-annexin V (5 μL) and propidium iodide (PI, 5 μL) working solution were added and then cells were incubated at room temperature for 5 min in the dark. After the incubation period, cells were analysed by flow cytometry, the annexin V-FITC binding was analysed by FITC signal detector (FL1) and PI staining by phycoerythrin emission signal detector (FL3). Apoptotic cells were identified as annexin V (+) and PI (−).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±s.d. from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by the two-tailed t-test or ANOVA for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered as showing a statistically significant difference between means.

Drugs and chemicals

Resveratrol, NG-mono-methyl-L-arginine (L-NAME), LY294002, BrdU and Medium 199 were all obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). ICI182780 (faslodex) was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA). Fibronectin and VEGF were obtained form Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA). DiI-acLDL was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). FITC-UEA-1 was obtained form Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-Akt-Ser473 and anti-Akt antibodies were obtained from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). All other reagents were of the highest purity commercially available.

Nomenclature

The nomenclature of drug and molecular targets in this article follows the recommendations of the BJP's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2008).

Results

Characterization of human EPCs

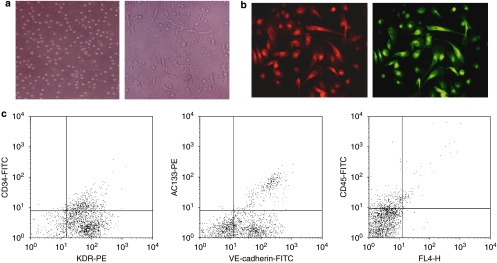

Total MNCs isolated and cultured for 7 days resulted in a spindle-shaped, endothelial cell-like morphology (Figure 1a). EPCs were characterized as adherent cells positive for acLDL uptake and UEA-1 binding using LSCM (Figure 1b). Cells were further identified by demonstrating the expression of KDR (82.1±6.4%), CD34 (29.0±5.7%), AC133 (19.1±4.8%), VE-cadherin (69.6±6.4%) and CD45 (17.8±4.0%; (Figure 1c) by flow cytometry.

Figure 1.

Characterization of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). (a, left panel) Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were plated on culture dishes just after isolation from peripheral blood ( × 200); (right panel) after 7 days in culture, attached cells exhibited a spindle-shaped, endothelial cells-like morphology ( × 200). (b) Adherent cells stained for uptake of acetylated low-density lipoprotein (acLDL; left panel, red, exciting wavelength 543 nm) or Ulex europaeus agglutinin (UEA-1) binding (right panel, green, exciting wavelength 477 nm) were assessed under a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM, × 400). (c) Flow cytometry analyses of adherent cells at day 7 of culture (n=6). Adherent cells were positive for KDR (82.1±6.4%), CD34 (29.0±5.7%), AC133 (19.1±4.8%), VE-cadherin (69.6±6.4%) and CD45 (17.8±4.0%). Data are percentage of positive cells.

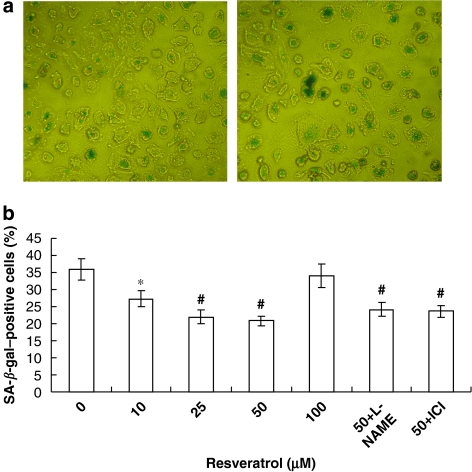

Resveratrol prevented EPC senescence

To assess the onset of senescence, acidic β-galactosidase was detected as a biochemical marker for acidification typical for the onset of cellular senescence (Greider, 1990; Dimri et al., 1995). Cultivation of EPCs resulted in an increase in SA-β-gal-positive cells after prolonged cultivation. As shown in Figure 2, resveratrol influenced EPCs senescence dose dependently, with a maximal inhibitory effect achieved at 50 μM. However, an increase in senescence was observed at 100 μM, suggesting the cytotoxic effect of resveratrol at an extremely high concentration. To examine whether NO synthase was involved in the resveratrol-associated anti-senescence effect, EPCs were pre-incubated with the selective NO sythase inhibitor-L-NAME (1 mM) 30 min before incubation with resveratrol at 50 μM. However, L-NAME failed to reverse the inhibitory effect of resveratrol. In addition, the oestrogen receptor (ER) antagonist ICI182780 (faslodex, 1 μM), which has no agonist properties, also did not alter the effect of resveratrol.

Figure 2.

Resveratrol prevents endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) senescence. Freshly isolated mononuclear cells were cultivated in Medium 199 supplemented with 20% foetal-calf serum and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). At day 4, cells were seeded onto methylcellulose plates and cultured with resveratrol in the indicated concentrations for 7 days. In some experiments cells treated with resveratrol were also exposed to NG-mono-methyl-L-arginine (L-NAME, 1 mM) or ICI182780 (1 μM). (a) Representative micrographs of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal)-positive cells (senescent cells) in EPCs treated with 50 μM resveratrol (left) or without resveratrol (right) are shown. (b) The number of blue cells was counted manually from a total of 200 cells. Data are means±s.d., n=6; *P<0.05, #P<0.01 vs control.

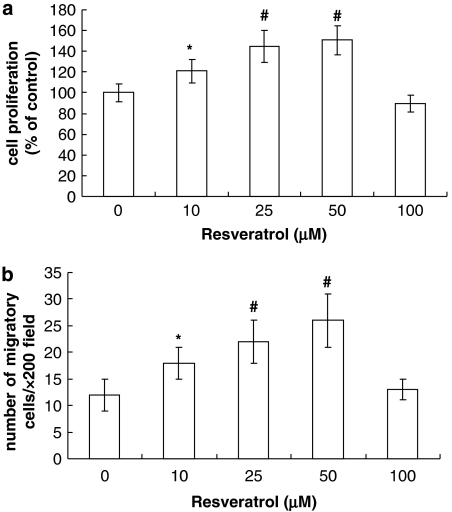

Effects of resveratrol on proliferation and migration of EPCs

Having demonstrated that resveratrol prevented the onset of senescence, we examined whether that would translate into an increase of proliferation and migration. The BrdU incorporation assay demonstrated that the mitogenic potential of EPCs treated with resveratrol exceeded that in untreated (control) EPCs—an effect that was dose dependent (Figure 3a). The modified Boyden chamber assay demonstrated that the migratory capacity of EPCs was also dose dependently increased by resveratrol (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Effects of resveratrol on proliferation and migration of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). Cultures of EPCs were treated with the indicated concentrations of resveratrol for 7 days before cells were harvested. (a) Cell proliferation was estimated from the incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) and calculated as a percentage of the control value. (b) Cell migration was assessed by a modified Boyden chamber assay. The data shown are mean±s.d., n=6; *P<0.05, #P<0.01 vs control.

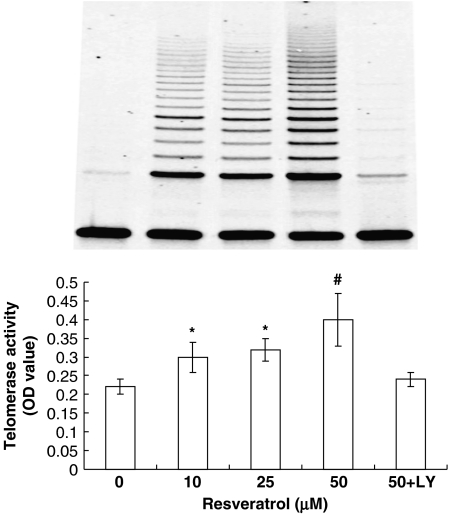

Effects of resveratrol on telomerase activity in EPCs

Cellular senescence is critically influenced by telomerase, which elongates telomeres, thereby counteracting the reduction in telomere length induced by each cell division. Therefore, we measured telomerase activity in EPCs using the TeloTAGGG PCR ELISAPLUS kit. As demonstrated in Figure 4, resveratrol dose dependently increased telomerase activity, with a maximal increase at 50 μM.

Figure 4.

Resveratrol induces the telomerase activity in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) through the PI3K-Akt pathway. Freshly isolated mononuclear cells (MNCs) were cultivated in Medium 199 supplemented with 20% foetal-calf serum and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). After 4 days of cultivation, cells were treated with indicated doses of resveratrol for 24 h with or without pre-treatment with LY294002 (10 μM). Telomerase activity was measured by the telomeric repeat-amplification protocol (TRAP) assay. A representative polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel (PAGE) figure of TRAP-PCR is shown on the top panel. Data are means±s.d., n=6. *P<0.05, #P<0.01 vs control.

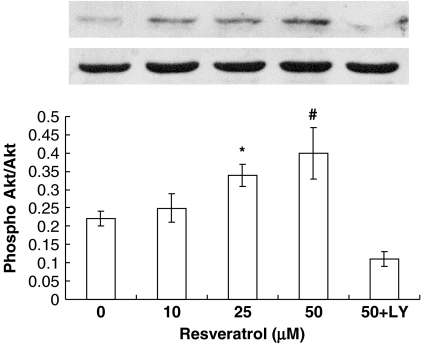

Resveratrol induced telomerase activity by the PI3K-Akt cascade

Recent studies have demonstrated that Akt is important in regulating cell senescence and telomerase activity (Kang et al., 1999; Breitschopf et al., 2001). Moreover, Akt has been shown to be important in atorvastatin-mediated prevention of EPC senescence (Assmus et al., 2003). To examine whether the PI3K-Akt cascade is involved in the resveratrol-induced telomerase activation, EPCs were pre-treated with the selective PI3K inhibitor-LY294002 (10 μM) 30 min before incubation with resveratrol. Interestingly, LY294002 clearly attenuated the increase in telomerase activity by resveratrol (Figure 4). We next investigated whether resveratrol would induce the phosphorylation of Akt, a downstream effector of PI3K. EPCs were stimulated with resveratrol at several concentrations for 24 h, and immunoblots were performed with anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) or anti-Akt antibody. As shown in Figure 5, stimulation with resveratrol led to dose-dependent phosphorylation of Akt, although it did not affect the total amount of Akt.

Figure 5.

Effect of resveratrol on Akt phosphorylation at Ser473. Mononuclear cells at day 4 were stimulated for 24 h with indicated concentrations of resveratrol, and phosphorylation of Akt was determined with a phospho-specific Akt antibody. A representative blot from six independent experiments is shown on the top panel. Data are expressed as a ratio of phospho-Akt over total Akt. Bars represent means±s.d. (n=6). *P<0.05, #P<0.01 vs control.

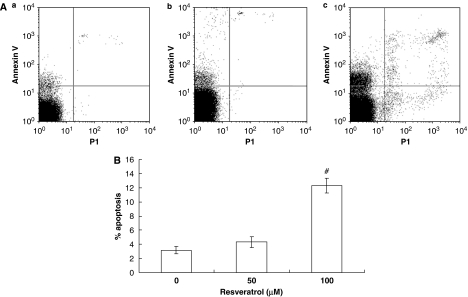

Effects of Resveratrol on apoptosis of EPCs

After the incubation period, apoptotic cells were evaluated by flow cytometry. Resveratrol at 50 μM had no obvious effect on EPC apoptosis. However, resveratrol at 100 μM significantly raised the apoptotic rate of cells, which is probably due to the cellular toxicity of resveratrol at high concentration (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of resveratrol on endothelial progenitor cell (EPC) apoptosis. (A) Representative dot plots of apoptotic cells from group of 0 (a), 50 (b) and 100 (c) μM resveratrol. (B) The levels of apoptotic rate of EPCs in different groups. Resveratrol (50 μM ) had no effect on apoptosis in EPCs. Values represent mean±s.d. (n=6). # P<0.05 vs control (0 μM resveratrol).

Discussion

Recent studies have provided increasing evidence that the functional regeneration of ischaemic tissue by improved neovascularization and tissue repair are critically dependent on the mobilization and integration of EPCs. Moreover, infusions of EPC populations that have been expanded ex vivo can limit the extension of scar tissue in ischaemic myocardium (Kawamoto et al., 2001) and improve the recovery of contractility, increase the arteriolar perfusion and decrease the pulmonary arterial pressure in pulmonary hypertension (Zhao et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007b), and thereby, may be useful as a novel therapeutic approach (Assmus et al., 2006). However, several studies have indicated that aging or senescence may limit the ability of EPCs to sustain neovascularization and repair of ischaemic tissue (Vasa et al., 2001; Edelberg et al., 2002; Hill et al., 2003; Scheubel et al., 2003), highlighting a potentially relevant feature of the endogenous repair process. This also posed an interesting question as to the value of therapies based on endogenous EPCs in either elderly patients or patients with atherosclerotic risk factors. Here, we have shown for the first time that resveratrol prevented the onset of EPC senescence, which was associated with a high proliferative and migrative capacity. However, resveratrol did not decrease the apoptosis of EPCs (Figure 6).

A recent study (Assmus et al., 2003) has shown that EPC senescence was associated with a reduction of numbers and impairment of activity in the EPCs. In addition, the proatherosclerotic risk factor, oxLDL, accelerated the onset of EPC senescence, leading to cellular dysfunction (Imanishi et al., 2004). Moreover, oestrogen has been shown to reduce EPC senescence, leading to the potentiation of proliferative activity and network formation (Imanishi et al., 2005b). Keeping these findings in mind, we speculated that changes in EPC senescence, but not apoptosis of EPCs, might partly account for the mechanisms by which resveratrol increases EPC numbers and activity.

The mechanisms by which resveratrol prevents the onset of cellular senescence and increases the capacity of EPCs seem to involve telomerase activity. Telomerase, an RNA-directed DNA polymerase, extends telomeres of eukaryotic chromosomes and delays the development of senescence. Recently, Murasawa et al. (2002) have revealed that overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery could result in a delay in senescence and recovery or enhancement of the regenerative properties of EPCs. In addition, oestrogen has been shown to significantly increase telomerase activity, which was considered to be associated with EPC senescence (Imanishi et al., 2005b). Our data demonstrated that resveratrol dose dependently increased telomerase activity, suggesting that resveratrol at appropriate concentrations might prevent EPC senescence through activation of telomerase.

However, the molecular mechanisms by which resveratrol increased telomerase activity remains to be determined. In this study, we have shown that resveratrol significantly increased Akt phosphorylation. Previous studies have demonstrated that the serine-threonine kinase, Akt, enhanced telomerase activity through phosphorylation of TERT in human umbilical cord endothelial cells and melanoma cells (Kang et al., 1999; Breitschopf et al., 2001). Besides the direct phosphorylation of TERT, Akt might also act against senescence by increasing the activity of the eNOS, as NO has been demonstrated to activate telomerase and delay endothelial-cell senescence (Vasa et al., 2000). However, inhibition of the NO synthase by L-NAME did not reverse the inhibitory effect of resveratrol (Figure 1), suggesting that the regulation of EPC senescence is independent of NO, which is in line with a previous report (Assmus et al., 2003). Taken together, our data indicated that resveratrol increased Akt phosphorylation in EPCs, which might lead to increased phosphorylation of TERT and enhance telomerase activity, thereby preventing the onset of senescence in EPCs.

However, inducing Akt phosphorylation would also mean that resveratrol could be influencing many other signal transduction mechanisms. Thus, the number of EPCs, in ex vivo cultures, could be reduced by the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and this reduction was not caused by apoptosis (Seeger et al., 2005). Moreover, inhibition of p38 significantly increased the proliferation of EPCs and reduced the numbers of cells expressing monocytic markers. Given the close links and complicated interaction between PI3K-Akt and ras-MAPK cascades in signal transduction networks, it is not possible to exclude the involvement of the p38 MAPK pathway in the effect of resveratrol on EPCs at present. In addition, the roles of relevant transcription factors that regulate cell-cycle control genes, such as cAMP-responsive element-binding protein and signal transducers and activators of transcription 3, which could be activated by MAPK or mammalian target of rapamycin remain to be further studied in future.

Resveratrol has been recognized as a phytoestrogen based on its structural similarities to diethylstilbestrol. It can bind to ERs to modulate the expression of oestrogen-regulated genes (Gehm et al., 1997; Klinge et al., 2003). Recent studies have documented that oestrogen reduces EPC senescence by activating telomerase (Imanishi et al., 2005b), so one might speculate that the inhibitory effect on EPC senescence was mediated by some oestrogenic property of resveratrol. However, in our study, the ER antagonist ICI182780 did not block the inhibitory effect of resveratrol, suggesting that the ERs were not involved in this effect of resveratrol. However, controversy about the oestrogenic behaviour of resveratrol is continuing. Ashby et al. (1999) showed that resveratrol possessed anti-oestrogen activity as it suppressed progesterone receptor expression induced by oestradiol. Moreover, most of the in vivo studies have failed to confirm the oestrogenic potential of resveratrol at physiological or even higher concentrations (Ashby et al., 1999; Freyberger et al., 2001). Taking all these findings together, we consider that the anti-senescence effect of resveratrol is more likely to be unrelated to its oestrogenic properties.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate that resveratrol delays the onset of senescence in EPCs, which appears to be related to activation of telomerase and Akt phosphorylation. The inhibition of EPC senescence by resveratrol in vitro may improve the functional activity of EPCs in a way that is important for potential cell therapy.

Abbreviations

- acLDL

acetylated low-density lipoprotein

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- DiI

dioctadecyl-3,3,3′3′-tetrametylindocarbocyanine

- EPCs

endothelial progenitor cells

- ER

oestrogen receptor

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- LSCM

laser scanning confocal microscope

- MNCs

mononuclear cells

- oxLDL

oxided low-density lipoprotein

- PI

propidium iodide

- SA-β-gal

senescence-associated β-galactosidase

- UEA-1

Ulex europaeus agglutinin

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 3rd edition (2008 revision) Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153 Suppl. 2:S1–S209. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, et al. Isolation of putative endothelial progenitor cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby J, Tinwell H, Pennie W, Brooks AN, Lefevre PA, Beresford N, et al. Partial and weak oestrogenicity of the red wine constituent resveratrol: consideration of its superagonist activity in MCF-7 cells and its suggested cardiovascular protective effects. J Appl Toxicol. 1999;19:39–45. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199901/02)19:1<39::aid-jat534>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmus B, Honold J, Schächinger V, Britten MB, Fischer-Rasokat U, Lehmann R, et al. Transcoronary transplantation of progenitor cells after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1222–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmus B, Urbich C, Aicher A, Hofmann WK, Haendeler J, Rössig L, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors reduce senescence and increase proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells via regulation of cell cycle regulatory genes. Circ Res. 2003;92:1049–1055. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070067.64040.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestrieri ML, Schiano C, Felice F, Casamassimi A, Balestrieri A, Milone L, et al. Effect of low doses of red wine and pure resveratrol on circulating endothelial progenitor cells. J Biochem. 2008;143:179–186. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benndorf R, Böger RH, Ergün S, Steenpass A, Wieland T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced migration and in vitro tube formation of human endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2003;93:438–447. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000088358.99466.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschopf K, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Pro-atherogenic factors induce telomerase inactivation in endothelial cells through an Akt-dependent mechanism. FEBS Lett. 2001;493:21–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JZ, Zhu JH, Wang XX, Zhu JH, Xie XD, Sun J, et al. Effects of homocysteine on number and activity of endothelial progenitor cells from peripheral blood. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelberg JM, Tang L, Hattori K, Lyden D, Rafii S. Young adult bone marrow-derived endothelial precursor cells restore aging-impaired cardiac angiogenic function. Circ Res. 2002;90:E89–E93. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020861.20064.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyberger A, Hartmann E, Hildebrand H, Krotlinger F. Differential response of immature rat uterine tissue to ethinylestradiol and the red wine constituent resveratrol. Arch Toxicol. 2001;11:709–715. doi: 10.1007/s002040000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehm BD, McAndrews JM, Chien PY, Jameson JL. Resveratrol,a polyphenolic compound found in grapes and wine, is an agonist for the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14138–14143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW. Telomeres, telomerase and senescence. Bioessays. 1990;12:363–369. doi: 10.1002/bies.950120803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Wang CQ, Fan HH, Ding HY, Xie XL, Xu YM, et al. Effects of resveratrol on endothelial progenitor cells and their contributions to reendothelialization in intima-injured rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47:711–721. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000211764.52012.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Zalos G, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, Finkel T. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Nishio I. Angiotensin II accelerates endothelial progenitor cell senescence through induction of oxidative stress. J Hypertens. 2005a;23:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200501000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Nishio I. Estrogen reduces endothelial progenitor cell senescence through augmentation of telomerase activity. J Hypertens. 2005b;23:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000176788.12376.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi T, Hano T, Sawamura T, Nishio I. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces endothelial progenitor cell senescence, leading to cellular dysfunction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:407–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SS, Kwon T, Kwon DY, Do SI. Akt protein kinase enhances human telomerase activity through phosphorylation of telomerase reverse transcriptase subunit. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13085–13090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto A, Gwon HC, Iwaguro H, Yamaguchi JI, Uchida S, Masuda H, et al. Therapeutic potential of ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cells for myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2001;103:634–637. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Wu F. Advances in quantification and characterization of telomerase activity by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol [TRAP] Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2595–2597. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge CM, Risinger KE, Watts MB, Beck V, Eder R, Jungbauer A. Estrogenic activity in white and red wine extracts. J Agri Food Chem. 2003;51:1850–1857. doi: 10.1021/jf0259821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, Takuma S, Burkhoff D, Wang J, et al. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med. 2001;7:430–436. doi: 10.1038/86498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murasawa S, Llevadot J, Silver M, Isner JM, Losordo DW, Asahara T. Constitutive human telomerase reverse transcriptase expression enhances regenerative properties of endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;106:1133–1139. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027584.85865.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orallo F, Alvarez E, Camina M, Leiro JM, Gomez E, Fernandez P. The possible implication of trans-resveratrol in the cardioprotective effects of long-term moderate wine consumption. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:294–302. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace-Asciak CR, Hahn S, Diamandis EP, Soleas G, Goldberg DM. The red wine phenolics trans-resveratrol and quercetin block human platelet aggregation and eicosanoid synthesis: implications for protection against coronary heart disease. Clin Chim Acta. 1995;235:207–219. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(95)06045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendurthi UR, Williams JT, Rao LV. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound found in wine, inhibits tissue factor expression in vascular cells: a possible mechanism for the cardiovascular benefits associated with moderate consumption of wine. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:419–426. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray PS, Maulik G, Cordis GA, Bertelli AA, Bertelli A, Das DK. The red wine antioxidant resveratrol protects isolated rat hearts from ischemia reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:160–169. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger FH, Haendeler J, Walter DH, Rochwalsky U, Reinhold J, Urbich C, et al. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase downregulates endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2005;111:1184–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157156.85397.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheubel RJ, Zorn H, Silber RE, Kuss O, Morawietz H, Holtz J, et al. Age-dependent depression in circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:2073–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu S, Ishida S, Hara M, Takahashi N, Yoshimatsu H, Sakata T, et al. Resveratrol, a red wine constituent polyphenol, prevents superoxide-dependent inflammatory responses induced by ischemia-reperfusion, platelet-activating factor, or oxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:810–817. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Kalka C, Masuda H, Chen D, Silver M, Kearney M, et al. Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nat Med. 1999;5:434–438. doi: 10.1038/7434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa M, Breitschopf K, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Nitric oxide activates telomerase and delays endothelial cell senescence. Circ Res. 2000;87:540–542. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, Adler K, Urbich C, Martin H, et al. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001;89:E1–E7. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter DH, Rittig K, Bahlmann FH, Kirchmair R, Silver M, Murayama T, et al. Statin therapy accelerates reendothelialization: a novel effect involving mobilization and incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;105:3017–3024. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018166.84319.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XB, Huang J, Zou JG, Su EB, Shan QJ, Yang ZJ, et al. Effects of resveratrol on number and activity of endothelial progenitor cells from human peripheral blood. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007a;34:1109–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XX, Zhang FR, Shang YP, Zhu JH, Xie XD, Tao QM, et al. Transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells may be beneficial in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007b;49:1566–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Huang Y, Zou J, Cao K, Xu Y, Wu JM. Effects of red wine and wine polyphenol resveratrol on platelet aggregation in vivo and in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 2002;9:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Neville R, Finkel T. Homocysteine accelerates endothelial cell senescence. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:20–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YD, Courtman DW, Deng Y, Kugathasan L, Zhang Q, Stewart DJ. Rescue of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension using bone marrow-derived endothelial-like progenitor cells: efficacy of combined cell and enos gene therapy in established disease. Circ Res. 2005;96:442–450. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000157672.70560.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]