Abstract

The potential energy profile for many complex reactions of proteins, such as folding or allosteric conformational change, involves many different scales of molecular motion along the reaction coordinate. Although it is natural to model the dynamics of motion along such rugged energy landscapes as diffusional (the Smoluchowski equation; SE), problems arise because the frictional forces generated by the molecular surround are typically not strong enough to justify the use of the SE. Here, we discuss the fundamental theory behind the SE and note that it may be justified through a master equation when reduced to its continuum limit. However, the SE cannot be used for rough energy landscapes, where the continuum limit is ill defined. Instead, we suggest that one should use a mean first passage time expression derived from a master equation, and show how this approach can be used to glean information about the underlying dynamics of barrier crossing. We note that the potential profile in the SE is that of the microbarriers between conformational substates, and that there is a temperature-dependent, effective friction associated with the long residence time in the microwells that populate the rough landscape. The number of recrossings of the overall barrier is temperature-dependent, governed by the microbarriers and not by the effective friction. We derive an explicit expression for the mean number of recrossings and its temperature dependence. Finally, we note that the mean first passage time can be used as a departure point for measuring the roughness of the landscape.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins are dynamic macromolecules that exhibit many scales of molecular motion (1–5). In the simplest reduction, just two can be considered (6,7). One is an overall profile of a free energy surface, which typically has minima at both ends of the process and has a maximum somewhere in between. There is, however, a shorter length scale: as the system proceeds from one side to another, it goes through local minima of the free energy surface. These minima, known as conformational substates or microstates, range from a few to hundreds. How then does one provide a formalism, which takes these two reaction scales into account?

This question has been dealt with in some detail previously. The standard picture is that of diffusion of the system, as described by a Smoluchowski equation (SE). The SE is, however, already a coarse-grained description of the process. What are the microscopic dynamics that lead to the SE description? The motivation for this article comes from the fact that one cannot uniquely identify from the SE the underlying microscopic dynamics without additional information. More specifically, in the limit of strong friction, one can derive the SE from the Klein-Kramers equation in phase space by adiabatic elimination (8). The Klein-Kramers equation is in turn derived from a Hamiltonian in which the system is bilinearly coupled to a harmonic bath with Ohmic friction (9). It is this friction that then reduces the reaction rate, as shown by Kramers in his famous article (10).

However, one can also derive the SE directly from a master equation description of the hopping between microstates (11,12). Such a description is valid as long as the barriers separating microstates are larger than the thermal energy kBT. In this description, there is no obvious friction coefficient that couples the system to some underlying bath. In fact, in Klein-Kramers dynamics, the friction must be strong to achieve the SE, but simulations have shown that the typical frictional force as derived from force autocorrelation functions is not very large when compared to typical molecular vibrations (13–17). Although these simulations have not been carried out for macromolecules, they do suggest that the Klein-Kramers equation is not the correct route to the SE applicable to protein isomerization reactions.

The differences between the two underlying mechanisms are not only philosophical in nature. For example, Zwanzig considered the effect of the roughness of the potential (18). His theory starts with the SE. He describes the roughness in terms of a free energy profile that has a random component. The roughness of the potential leads to a non-Arrhenius increase in the mean first passage time and thus a decrease in the reaction rate, beyond that expected from a simplified Kramers analysis. These ideas were further developed by Bryngelson and Wolynes (19), who start their analysis with a generalized master equation formalism, then use the continuous-time random walk description to estimate mean first passage times for protein folding. Hyeon and Thirumalai (20) suggested how the roughness can be measured by applying an external force on the biosystem. This was then actually achieved by Nevo et al. (21). If, however, the underlying dynamics of the SE is a master equation and the barriers of the potential energy profile are uncorrelated, then the derivative of the potential is ill defined in the continuum limit and the SE seems to become meaningless. What then is the effect of the roughness? Can it really be measured?

The two different mechanisms lead also to interpretational problems. Hyeon and Thirumulai (20) use the Klein-Kramers dynamics to argue that one can extend a proposed method for measurement of the roughness, also for moderate friction, by employing the Kramers moderate friction expression for the rate. What, however, is the source of this friction? Sagnella et al. (17) have noted that the velocity autocorrelation function relaxes with two timescales. A short timescale is associated with the molecular friction, and a longer timescale is associated with the residence time in the microstates. In the master equation approach, the friction is associated with the time the system is trapped in each of the microstates. Since this time is very long, as compared to molecular timescales, the friction is indeed strong, the process of transformation from reactant to product is indeed diffusive, and the use of the SE is justified, with some caveats.

The derivation from a kinetic equation raises another interesting question (6). Kramers showed that strong friction reduces the reaction rate. He derived a prefactor in the rate expression that is inversely proportional to the friction. It is also well understood that this prefactor comes as a correction, which accounts for the multiple recrossings of the transition state (22,23). How do the recrossings as estimated by using master equation dynamics (7) relate to recrossing as estimated using the Kramers formalism?

The purpose of this article is to clarify the usage of the SE in the context of protein reaction dynamics. We argue that the SE equation is valid for such processes only when derived from the master equation. The molecular friction may not be sufficiently strong to justify the usage of the SE as derived from the Klein-Kramers equation. This leads to a number of conclusions:

The free energy profile in the Smoluchowski equation is that of the barriers (separating microstates) only.

The strong friction, which justifies usage of the Smoluchowski equation, is a result of the long trapping times in the microstates, which separate reactants from products.

The effective friction coefficient is temperature-dependent, but it does not have any affect on the recrossing probability.

Recrossing exists in the discrete limit also (we present an explicit expression for the mean number of recrossings of the topmost barrier); it is temperature-dependent and depends on the number of barriers between microstates whose energy is kBT or less of the topmost barrier energy.

In the presence of spatially dependent friction, the equilibrium distribution of the SE depends on the friction.

Finally, we conclude that one should use the mean first passage time expression, which is valid for the master equation (24) for estimating rate constants rather than an approach whose starting point is the SE. The mean first passage time expression derived from the master equation remains valid in the presence of a rough energy landscape.

In the next section, The Master Equation, we review results that are known for the discretized master equation description of the process. In The Smoluchowski Equation, we consider the continuum limit. We end with a summary in the Discussion section.

THE MASTER EQUATION

Our model for biological reactions is that of a reactant and product. The route leading from the reactant (protein in conformation A) to the product (protein in conformation B) passes through a rugged landscape, composed of many shallow potential wells and barriers separating them. The overall rough structure of the potential along the reaction coordinate is that of a double well potential in which the two wells are separated by a barrier. However, along the way there are many (N) local minima, whose local well-depth is assumed to be larger than kBT . We can safely assume that the system gets trapped in such a microwell = microstate, before continuing on its journey. Consider then the jth microstate. It has a well separated by barriers from the rest of the chain. The rate of escape to the left will be denoted as

|

(1) |

while the rate of escape to the right is denoted as

|

(2) |

where the values Vj±1/2 are the barrier heights to either direction, Vj is the well-depth of the jth microstate, and β = 1/kBT. The prefactor νj is a frequency that may include in it the effect of the local microscopic friction, which typically appears in the Klein-Kramers equation (25). That is, here we do not consider the microstates themselves to have rugged surfaces.

Anticipating the continuum limits, we may rewrite these rates also as

|

(3) |

and

|

(4) |

where we used the notation

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

Initially, the population of reactants (j = 0) is unity; the population of all other local minima (j = 1, … , N) is zero. We then put a sink at the products (j = N + 1), so that ultimately, all the population disappears in the sink, precisely the boundary conditions which validate a mean first passage time estimate for the rate of reaction. Allowing for nearest neighbor transitions only, the time-dependent population of the jth microstate is described in terms of the master equation

|

(8) |

The detailed balance condition

|

(9) |

assures that, at equilibrium, there is no change, which is that  We then find that the equilibrium distribution is

We then find that the equilibrium distribution is

|

(10) |

The expression for the mean first passage time for the discrete dynamics is well known (24,26), and in our notation it becomes

|

(11) |

As shown in Appendix A, the rate expression derived by Zhou et al. (see their Eq. 7 in (7)) is (apart from a steepest-descent-like approximation) identical to the inverse of the mean first passage time expression of Eq. 11.

The standard transition state theory (TST) expression for the rate in the absence of recrossings of the transition state is obtained by using the usual steepest descent arguments. We assume that the frequency factors νk do not vary much as one moves from one microstate to the next one. We also assume that the reactant well-depth (V0) is much lower than the well-depth of any of the microstates so that the second sum is  If we further assume that only the topmost barrier (with barrier height V‡, located at j = j‡) contributes to the remaining sum, then we find that the mean first passage time is

If we further assume that only the topmost barrier (with barrier height V‡, located at j = j‡) contributes to the remaining sum, then we find that the mean first passage time is

|

(12) |

and this is the standard TST limit.

In light of this, are recrossings of the topmost barrier at all important in this discrete model? Yes. When the landscape is rough, the top barrier height V‡ is not unique, in the sense that there are, say, M ≫ 1 microstates whose barrier heights are within kBT or less of the maximal barrier. This number of states M will depend on the temperature. For a static landscape, the larger the temperature, the larger the magnitude of M. One can then no longer ignore these additional microstates that are in the barrier region (27). They add to the mean first passage time since motion between them is diffusive.

As discussed in Pollak and Talkner (23), in the diffusive limit, the mean first passage time will be increased relative to the TST estimate. This increase is related to recrossings of the topmost barrier. The probability flux leaving reactants (products) may be divided into subsets that cross the topmost barrier k times. The mean number of crossings of the topmost barrier is denoted as 〈NR〉, (〈NP〉). Similarly, the probability flux leaving the topmost barrier may be divided into subsets that recross it l times. The average number of recrossings of the topmost barrier is denoted as 〈Nc〉. The two are not identical, but related to each other:

|

(13) |

If one assumes that the probability of reaching either reactants or products from the topmost barrier without further recrossing is the same for both, and that subsequent recrossings are independent of each other, then the mean first passage time will be enhanced by the factor (2 〈Nc〉 + 1). In the TST limit, there are no recrossings since 〈Nc〉 = 0, and one regains the TST limit. The factor of 2 reflects the fact that having reached the top barrier, one has equal probability to go back toward either direction.

Consider now, the mean first passage time expression. Using the steepest descent estimate as above, one has that

|

(14) |

so that the mean number of recrossings is given by the expression

|

(15) |

To estimate the enhancement, let us assume that the microstate barriers roughly follow the shape of a parabolic barrier, that is

|

(16) |

where we assumed that the distance between microstates is l. The summation over states can now be roughly estimated as an integral and we find that

|

(17) |

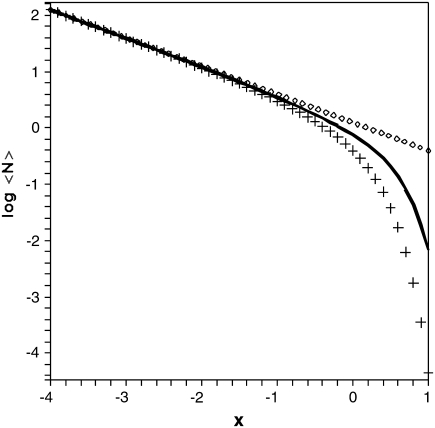

In this limit, in which the temperature is not too low (see Fig. 1), recrossings enhance the mean first passage time by the temperature-dependent factor  A quantitative comparison with the exact mean number of recrossings is provided in Appendix B.

A quantitative comparison with the exact mean number of recrossings is provided in Appendix B.

FIGURE 1.

The decadic logarithm of the mean number 〈Nc〉 of barrier recrossings for a parabolic barrier as a function of the logarithmic dimensionless barrier parameter x = log10mβω‡2l2 was numerically determined by means of Eq. 52 (crosses) and the approximate formula (Eq. 15) (solid line). The dotted line displays the asymptotic relation (Eq. 53).

THE SMOLUCHOWSKI EQUATION

The Langevin equation route

The Smoluchowski equation for a system with mass m and coordinate q moving on a force field with potential V(q) is

|

(18) |

Here, γ is the friction coefficient and ρ(q,t) is the distribution function for finding the particle at position q at the time t. We assume that the potential function has a minimum at q = −a, a barrier located at q = 0, and a sink located at some value of the coordinate (q+), which is well beyond the location of the barrier. The mean first passage time from the well to the product is given by the expression

|

(19) |

The principal contribution to the integration over q comes from the barrier top, while the major contribution for the integration over q′ comes from the minimum at  Approximating the barrier around its top as parabolic,

Approximating the barrier around its top as parabolic,  for

for  —and around the well as harmonic,

—and around the well as harmonic,  for

for  —we have that the mean first passage time is

—we have that the mean first passage time is  The prefactor

The prefactor  is twice the average number of crossings of the barrier induced by the friction (23).

is twice the average number of crossings of the barrier induced by the friction (23).

The Smoluchowski equation is often derived as the large friction limit of the Klein-Kramers equation in phase space, which in turn is equivalent to the Langevin equation

|

(20) |

where F(t) is a Gaussian random force with zero mean and correlation function  The Langevin equation in turn may be derived from the Hamiltonian of the system bilinearly coupled to a harmonic bath. Furthermore, if the friction is spatially dependent, in the large friction limit the SE then takes the form (28)

The Langevin equation in turn may be derived from the Hamiltonian of the system bilinearly coupled to a harmonic bath. Furthermore, if the friction is spatially dependent, in the large friction limit the SE then takes the form (28)

|

(21) |

from which it is evident that the spatial dependence of the friction does not affect the equilibrium distribution. This is to be expected when one thinks of the friction in terms of an interaction with a bath, and the potential as the free energy along the reaction coordinate. The free energy is an averaged quantity that already includes any bath effects and therefore the friction does not affect the equilibrium distribution.

The master equation route

The starting point is the master equation as given in Eq. 8. The jth well is located at the coordinate value xj. We denote the distance between two consecutive wells as lj, such that the barrier denoted by j – 1/2 is located at xj−1 +  = xj –

= xj –  and lj =

and lj =  +

+  To derive the continuum limit of the master equation one lets the distances lj tend to 0, while the rates Γj tend to infinity, keeping the diffusion coefficient

To derive the continuum limit of the master equation one lets the distances lj tend to 0, while the rates Γj tend to infinity, keeping the diffusion coefficient  constant. The physical picture one has in mind is that of a diffusing particle, with a well-defined diffusion coefficient.

constant. The physical picture one has in mind is that of a diffusing particle, with a well-defined diffusion coefficient.

The master equation is rewritten in terms of the probability p(xj,t) = nj(t) of finding the system at the point xj at the time t,

|

(22) |

Expanding all variables around their value at xj up to quadratic terms in lj, we have that

|

(23) |

|

(24) |

|

(25) |

We then note that

|

(26) |

where we stress that this derivative comes from the difference in consecutive barrier heights separating microstates. The potential energy function that will appear in the corresponding SE is the profile of the barriers. It does not include in it information about the wells. Expanding the master equation to second order in lj, one then finds that the corresponding SE for the probability density ρ(x, t) = p(x, t)/l(x) is

|

(27) |

where D(x) is the continuum analog of Dj. One may then define an effective space-dependent friction coefficient as

|

(28) |

to write down the final form of the SE as

|

(29) |

We thus see explicitly that the friction is proportional to the inverse of the escape rate from a microstate. This inverse is proportional to the residence time in the microstate, which is long compared to the characteristic microstate prefactor νj.

Equation 29 differs from the SE derived from the Klein-Kramers equation as given in Eq. 21 and used for example in Best et al. (29). The equilibrium distribution here is

|

(30) |

This is not an error. It coincides with the continuum limit of the equilibrium solution (Eq. 10) of the master equation (for similar considerations that assure the correct equilibrium limit see Hänggi et al. (12)). That Eq. 30 expresses the correct equilibrium limit distribution is a direct consequence of the fact that the friction γ*(x) in this derivation comes from the residence time in the microstates. More specifically, the prefactor, by definition is

|

(31) |

where the notation ΔU(x) comes for the difference between the average barrier height of the microstate and its well-depth. In other words, the equilibrium population is proportional to the Boltzmann factor for the well-depth and this is what it should be.

We also note that the friction coefficient γ*(x) is strongly temperature-dependent. This, too, is very different from the temperature-independent coefficient that appears in the Klein-Kramers equation and used in the literature (25,29).

Recrossings

In the presence of space-dependent friction, the mean first passage time expression as derived from the SE given in Eq. 29 is

|

(32) |

The steepest descent approximation here is a bit tricky, since as already stressed above, the potential V(q) appearing in this expression is the profile of the barrier energies and does not include in it any wells. Using the definition of the friction coefficient as given in Eq. 28 (and assuming that the length scale l(x) is independent of x), we may rewrite the mean first passage time as

|

(33) |

The second expression in brackets reduces within a steepest descent estimate to the standard TST expression while the first one expresses the enhancement of the mean first passage time due to recrossings of the highest barrier. The continuum limit for the mean number of recrossings as given in Eqs. 14 and 15 then becomes

|

(34) |

It is important to note that the number of recrossings is not proportional to the friction coefficient γ*(q), as would be the case for the Klein-Kramers equation. The friction coefficient does not even appear in the expression for the recrossings.

We have thus shown that

The discrete jump model and the continuum model lead in the continuum limit to the same equilibrium distribution and to the same mean first passage time.

The mean first passage time is increased due to recrossing of the highest barrier between reactants and products.

The number of recrossings is temperature-dependent; in the discrete limit, it decreases to zero as the temperature is lowered to zero. Lowering of the temperature diminishes the probability of recrossing the central barrier due to the Arrhenius factor of neighboring barriers.

Rough energy landscape

The derivation of the SE as given above assumes that the potential barrier heights vary smoothly from one microstate to the other. If this is not true, and more specifically, for a model of random, spatially uncorrelated potentials, then one cannot go to the continuum limit and the SE equation is not valid. This might seem to imply that Zwanzig's major result (18), which is that the rough energy landscape leads to a non-Arrhenius temperature reduction of the rate, is incorrect. In fact, his point of departure—the SE—is not valid; however, the expression for the mean first passage time is more general than the SE. To understand the mean first passage time in the presence of the rough energy landscape, one should take as the starting point the mean first passage time expression for the master equation, as given in Eq. 11. One may then average this mean first passage time, over the roughness of the potential.

Following Zwanzig, we assume that the barrier energy Vj+1/2 has a mean value  and Gaussian fluctuations δV distributed as

and Gaussian fluctuations δV distributed as  where

where  is the root mean-squared roughness. We will further simplify and assume that the potential minima of the microstates are not rough. One then has that the mean first passage time, when averaged over the roughness of the barriers, is

is the root mean-squared roughness. We will further simplify and assume that the potential minima of the microstates are not rough. One then has that the mean first passage time, when averaged over the roughness of the barriers, is

|

(35) |

and this is identical to the result derived by Zwanzig.

DISCUSSION

Diffusion is central to the study of dynamics in biological systems. Rather than just assuming that one can use a diffusion equation, we tried to provide an answer for its validity. We noted that the source is not the interaction of the system with a surrounding bath. Instead, the friction comes from the long residence times of the system as it traverses from one microstate to the next. This time is very long when compared to the timescales νj, which characterize the microstates and therefore leads to the diffusive character of the dynamics as described by the SE.

This does not mean that the “standard friction”, which results from the interaction of the system with the bath does not exist or is uninteresting. The standard friction guarantees that the microstates equilibrate locally on a timescale that is rapid compared with the escape time from the microstate. This in turn justifies the usage of a master equation. However, the diffusional property is a result of the long residence times, which are mainly governed by the barrier heights separating the microstates rather than by the standard friction.

This observation is not new in the context of the physics of fluids. It underlies Zwanzig's theory (30), which relates the self-diffusion to the longitudinal and shear viscosities in liquids (31). We believe that it is not generally appreciated in the context of biological reactions, which occur on a rough energy landscape. This lack of appreciation manifests itself through a number of observations considered in this article. We showed that the effective friction is temperature-dependent. This temperature dependence has to do with the residence time in the microstates, which increases exponentially as the temperature is lowered. We also showed that in contrast to the results obtained from the Klein-Kramers equation in the strong friction limit, here the average number of recrossings of the highest barrier is temperature-dependent. The source for this temperature dependence is the effective number of microstates whose barrier energies are within kBT of the dominant barrier height. This number increases with increasing temperature and underlies diffusive recrossing of the topmost barrier.

Our analysis points out that one should not always assume that the Smoluchowski equation is valid for biological systems. In fact, when the landscape is sufficiently rough so that barrier heights can be considered to be independent random variables, the SE is no longer valid because the spatial derivative of the barrier heights is not well defined. However, the idea that the roughness can be measured via reaction rates is correct. The more general concept validating this is the mean first passage time expression, which holds also for rough energy landscapes. It does not assume any continuity in the potential. Zwanzig's result (18) that the roughness increases the mean first passage time in a non-Arrhenius fashion is correct, since it can be derived directly from the mean first passage time expression.

In this article we considered only a one-dimensional model. Can one really describe the complexity of change in a biological system with one-dimensional models? The one-dimensional picture is an oversimplification but remains instructive because it reveals the essential physics responsible for the diffusional properties of motion on rough energy landscapes. There is nothing though that limits application of the same ideas to more realistic multidimensional descriptions. Specifically, the same ideas are readily derived also in two dimensions by following the formalism of Schumaker and Watkins (32), which would then lead to diffusion in two dimensions.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant of the Israel Science Foundation (to E.P.) and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant No. NS-23513 to A.A).

APPENDIX A: THE MEAN FIRST PASSAGE TIME

For the same model as considered in The Master Equation, Zhou et al. (7) derived an expression for the reaction rate, valid in the limit that the rate of escape from the initial well (reactant) Γ1←0 is much smaller than the rates of jumping between microstates. Denoting

|

(36) |

(where, for the second equality in the right-hand side, we used Eqs. 1 and 2), they find that the rate is given by the expression

|

(37) |

where

|

(38) |

We then see that

|

(39) |

Noting that

|

(40) |

and as discussed following Eq. 11 that the reactants' well is much lower in energy then the wells of the microstates, we have that

|

(41) |

so that finally

|

(42) |

which is just the mean first passage time expression as given in Eq. 11.

APPENDIX B: THE AVERAGE NUMBER OF BARRIER RECROSSINGS

By definition, a recrossing of a barrier implies that one must have visited this state before. We therefore consider processes which start at the barrier and then count the number of returns to the barrier before eventually reaching either the reactant or the product states, j = 0 or j = N + 1, respectively. Once one of these states has been reached, the process, as described by the master equation (Eq. 8), would become trapped there for a long time, on the order of half the inverse rate until reescaping and revisiting the barrier. To characterize just the first episode of recrossings we stop the process at its first arrival at reactants or products. The probability p(j, t|j‡) to find such a process at time t in a particular state between reactants and products is governed by the master equation

|

(43) |

with the initial condition

|

(44) |

The master matrix M = (Mj,j′) allows for absorption at the reactant and product states, i.e., for the cancellation of the process once it reaches either of these states. Otherwise it is determined by Eqs. 3 and 4. Consequently, it has the form

|

(45) |

The frequency of reaching the barrier at a time t > 0, say, from its left side, is given by the probability p(j‡ – 1, t|j‡) to be occupied, multiplied by the transition probability  to move from there to the right (33). The analogous expression holds for the frequency with which the barrier is reached from the right side. Therefore the frequency of recrossing the barrier at time t is given by

to move from there to the right (33). The analogous expression holds for the frequency with which the barrier is reached from the right side. Therefore the frequency of recrossing the barrier at time t is given by

|

(46) |

The integral of W(j‡, t) over all positive times yields the average number of barrier recrossings 〈Nc〉, which is thus given by

|

(47) |

Using the master equation (Eq. 43) one can express the frequency of recrossings by  Integration of the first term by parts gives for the average number of recrossings

Integration of the first term by parts gives for the average number of recrossings

|

(48) |

where

|

(49) |

denotes the mean total sojourn time in the state j of a process starting in the state k, with initial condition p(j, 0|k) = δj, k. Note that this time is finite for all states j because it is bounded by the total mean lifetime of the process which itself is finite due to the presence of the absorbing states at reactants and products. Multiplying Eq. 49 by the master matrix M, one obtains, by means of the master equation (Eq. 43) and a partial integration, the following algebraic equation for the matrix of sojourn times:

|

(50) |

having the formal solution

|

(51) |

where M−1 denotes the inverse master matrix. The latter exists because of the presence of the absorbing states. Combining Eqs. 48 and 51, we obtain

|

(52) |

for the average number of recrossings.

We determined the average number of recrossings by means of a numerical inversion of the master matrix M for a parabolic barrier of the shape specified by Eq. 16 for different values of the dimensionless barrier parameter βmω‡2l2. The prefactors of the transition rates, which, for the sake of simplicity, were assumed to be constant, i.e., Γj = Γ, determine the timescale of the sojourn times 𝒯j,k. They exactly cancel, however, from the result for the mean number of recrossings. In Fig. 1, the results are compared to the predictions of Eq. 15 and its high temperature asymptotic value

|

(53) |

which results by means of the approximation (Eq. 17).

For sufficiently large temperatures, i.e., for small enough values of the dimensionless barrier parameter βmω‡2l2, the discrete formula Eq. 15 as well as its asymptotic approximation were found to be in excellent agreement with the numerically exact mean number of recrossings. For lower temperatures, the discrete expression (Eq. 15) provides a useful approximation, which always gives an upper bound to the actual number of recrossings.

Editor: Steven D. Schwartz.

References

- 1.Frauenfelder, H., F. Parak, and R.-D. Young. 1988. Conformational substates in proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 17:451–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frauenfelder, H., S.-G. Sligar, and P.-G. Wolynes. 1991. The energy landscapes and motions of proteins. Science. 254:1598–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenimore, P.-W., H. Frauenfelder, B.-H. McMahon, and R.-D. Young. 2005. Proteins are paradigms of stochastic complexity. Physica A. 351:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dioumaev, A.-K., and J.-K. Lanyi. 2007. Bacteriorhodopsin photocycle at cryogenic temperatures reveals distributed barriers of conformational substates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:9621–9626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baba, A., and T. Komatsuzaki. 2007. Construction of effective free energy landscape from single-molecule time series. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:19297–19302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerbach, A. 2005. Gating of acetylcholine receptor channels: Brownian motion across a broad transition state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:1408–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou, Y., J. E. Pearson, and A. Auerbach. 2005. Φ-Value analysis of a linear, sequential reaction mechanism: theory and application to ion channel gating. Biophys. J. 89:3680–3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Risken, H. 1984. The Fokker-Planck Equation. Springer Series in Synergetics, Vol. 18. Springer, Berlin.

- 9.Zwanzig, R. 1973. Nonlinear generalized Langevin equations. J. Stat. Phys. 9:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramers, H. A. 1940. Brownian motion in a field of force and the diffusion model of chemical reactions. Physica. 7:284–304. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Kampen, N.-G. 1981. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry. North-Holland, Amsterdam, New York.

- 12.Hänggi, P., H. Grabert, P. Talkner, and H. Thomas. 1984. Bistable systems: master equation and Fokker-Planck modeling. Phys. Rev. A. 29:371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straub, J. E., M. Borkovec, and B.-J. Berne. 1988. Molecular dynamics study of an isomerizing diatomic in a Lennard-Jones Fluid. J. Chem. Phys. 89:4833–4847. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berne, B.-J., M.-E. Tuckerman, J.-E. Straub, and A.-L.-R. Bug. 1990. Dynamics friction on rigid and flexible bonds. J. Chem. Phys. 93:5084–5095. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gershinsky, G., and E. Pollak. 1997. Unimolecular reactions in the gas and liquid phases: a possible resolution to the puzzles of the trans-stilbene isomerization. J. Chem. Phys. 107:812. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koneshan, S., R. Lynden Bell, and J.-C. Rasaiah. 1998. Friction coefficients of ions in aqueous solution at 25°C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:12041–12050. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagnella, D.-E., J.-E. Straub, and D. Thirumulai. 2000. Time scales and pathways for kinetic energy relaxation in solvated proteins: application to carbonmonoxy myoglobin. J. Chem. Phys. 113:7702–7711. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwanzig, R. 1988. Diffusion in a rough potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85:2029–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryngelson, J.-D., and P.-G. Wolynes. 1989. Intermediates and barrier crossing in a random energy model (with applications to protein folding). J. Phys. Chem. 93:6902–6915. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyeon, C., and D. Thirumalai. 2003. Can energy landscape roughness of proteins and RNA be measured by using mechanical unfolding experiments? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:10249–10253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nevo, R., V. Brumfeld, R. Kapon, P. Hinterdorfer, and Z. Reich. 2005. Direct measurement of protein energy landscape roughness. EMBO Rep. 6:482–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gertner, B.-J., K.-R. Wilson, and T.-J. Hynes. 1989. Non-equilibrium solvation effects on reaction rates for model SN2 reactions in water. J. Chem. Phys. 90:3537–3558. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollak, E., and P. Talkner. 1995. Transition state recrossing dynamics in activated rate processes. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 51:1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hänggi, P., P. Talkner, and M. Borkovec. 1990. Reaction rate theory: fifty years after Kramers. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62:251–342. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klimov, D. K., and D. Thirumulai. 1997. Viscosity dependence of the folding rates of proteins. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79:317–320. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson F. H., H. Eyring, M. J. Polissar. 1954. The Kinetic Basis of Molecular Biology. John Wiley and Sons, New York. 754–755.

- 27.Hershkovitz, E., and E. Pollak. 2000. Kramers turnover theory for bridges. Ann. Phys. 9:764–779. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sancho, J.-M., M. San Miguel, and D. Dürr. 1982. Adiabatic elimination of Brownian particles with nonconstant damping coefficients. J. Stat. Phys. 28:291–305. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Best, R.-B., and G. Hummer. 2006. Diffusive model of protein folding dynamics with Kramers turnover in rate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96:228104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zwanzig, R. 1983. On the relation between self-diffusion and viscosity of liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 79:4507–4508. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabani, E., J.-D. Gezelter, and B.-J. Berne. 1997. Calculating the hopping rate for self-diffusion on rough potential surfaces: cage correlations. J. Chem. Phys. 107:6867–6876. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schumaker, M.-F., and D.-S. Watkins. 2004. A Framework model based on the Smoluchowski equation in two reaction coordinates. J. Chem. Phys. 121:6134–6144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talkner, P. 2003. Statistics of entrance times. Physica A. 325:124–135. [Google Scholar]