Abstract

Infectious bronchitis (IB) is one of the important viral diseases of chickens, and in spite of regular vaccination, IB is a continuous problem in Canadian poultry operations. In an earlier study using sentinel chickens we determined the incidence of infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) in Ontario commercial layer flocks. The objective of this study was to determine the pathogenicity of 5 nonvaccine-related IBV isolates recovered from the sentinel birds. The clinical signs, gross, and histological lesions in specific pathogen-free chickens indicated that all 5 isolates caused mild lesions in the respiratory tract. An important finding of this study was the significantly lower average daily weight gain among virus-inoculated groups of chickens during the acute phase of infection. Based on sequences of part of the S1 gene IBV-ON2, IBV-ON3, and IBV-ON5 formed a cluster and they were closely related to strain CU-82792. IBV-ON4 had 98.7% identity with the strain PA/1220/9, a nephropathogenic variant.

Résumé

La bronchite infectieuse (IB) est une des maladies virales importantes en production avicole et malgré une vaccination régulière elle continue de poser problème dans les opérations avicoles canadiennes. Lors d’une étude antérieure utilisant des poulets sentinelles, nous avons déterminé l’incidence du virus de la bronchite infectieuse (IBV) dans les troupeaux de pondeuses commerciales en Ontario. L’objectif de la présente étude était de déterminer la pathogénicité de cinq isolats d’IBV, non-apparentés aux vaccins, provenant des oiseaux sentinelles. Les signes cliniques, ainsi que les lésions macroscopiques et microscopiques observés chez des poulets exempts d’agents pathogènes spécifiques, indiquaient que les cinq isolats produisaient de légères lésions dans le tractus respiratoire. Une observation importante de la présente étude était le gain de poids moyen quotidien plus faible chez les groupes de poulets durant la phase aiguë de l’infection. Sur la base de la séquence d’une partie du gène S1, IBV-ON2, IBV-ON3 et IBV-ON5 formait un regroupement et ils étaient étroitement reliés à la souche CU-82792. IBV-ON4 était identique à 98,7 % avec la souche PA/1220/9, un variant néphropathogène.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

The enveloped infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is classified in the order Nidovirales, family Coronaviridae, and it is the type species of the genus Coronavirus (1). The size of the positive sense, single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) genome of coronaviruses ranges from 27 to 31 kb (2). The 27.6 kb complete nucleotide sequence of the Beaudette strain of IBV was reported by Boursnell et al (3). The nucleocapsid (N) protein is one of the major structural proteins of the virion, and since the N gene is highly conserved even among IBV isolates of different serotypes, it is often the target for nucleic acid based virus identification in diagnostic laboratories. The spike (S) glycoprotein is another major structural protein of the virion, and it is post-translationally cleaved into S1 globular and S2 stalk polypeptides (4). While the S2 subunit is conserved, the S1 subunit generally varies by up to 23% at the amino acid (aa) level among viruses of the same serotype (5,6). Moreover, some isolates such as a Dutch strain (D1466) and certain Delaware variant viruses showed only 51% to 56% aa identity with IBV strains of other serotypes (7,8). Sequence analysis of the S1 portion of the genome of hundreds of isolates belonging to the many different serotypes of IBV worldwide has been carried out to study and determine phylogeny, evolution, antigenic, and genetic relatedness and virulence of this important poultry pathogen (9–11).

Infectious bronchitis (IB), an important respiratory disease of chickens, is characterized by increased oculo-nasal secretion and excess mucus in the trachea accompanied by decreases in both weight gain and feed efficiency (12,13). The virus also replicates in the oviduct and testes of infected birds resulting in reduced egg production and fertility (12,14). Moreover, some IBV strains can infect the kidney causing significant mortality (15). The establishment of persistent infections in chickens has also been reported (16).

Live attenuated and inactivated vaccines have been available to control IB for many decades. The most commonly used vaccine strains are representatives of the Massachusetts and Connecticut antigenic groups, and they are reasonably effective in controlling clinical disease and production losses associated with IBV infection (17–19). However, the continuous emergence of new IBV variants as a consequence of mutation and recombination of the virus genome remains a problem for both the poultry industry and vaccine manufacturers (20).

Infectious bronchitis outbreaks are often reported in North America, and the molecular characterization of some isolates from Quebec showed that they were caused by new IBV strains (21,22). In 2002 Stachowiak et al (23,24) used sentinel chickens to recover field virus and investigate the diversity of IBV strains in 13 Ontario commercial layer flocks with a history of egg production losses or respiratory disease, or both. Infectious bronchitis viruses were identified by N-gene specific reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and the restriction enzyme digestion patterns of the amplified S1 gene products indicated that the 11 isolated viruses were different from the reference strains and none of the isolates were vaccine strains. The objective of this study was to determine the pathogenicity of 5 of these 11 Ontario field isolates in specific pathogen-free (SPF) layer chickens. The measurable outcomes included clinical signs, pathological lesions, and the effects of viral infection on weight gain over the period of the experiment.

Materials and methods

Viruses

Five Ontario field isolates of IBV obtained through a sentinel bird surveillance study were selected from the archived collection of the Department of Pathobiology, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Canada (24). The viruses were designated as IBV-ON1, IBV-ON2, IBV-ON3, IBV-ON4, and IBV-ON5.

Virus propagation and titration in embryonated eggs

Each virus isolate was propagated in 10-day-old embryonated SPF chicken eggs (Hy-Vac, Adel, IA, USA) according to standard methods (25) and the virus titres were determined by the Reed and Muench method (26) in embryonated eggs and expressed as embryo infectious dose 50 per mL (EID50/mL).

RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from allantoic fluid or lung tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, New York, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Amplification of the N gene by a two-step RT-PCR was carried out with oligonucleotide primers published by Handberg et al (27) and following the method described by Stachowiak (23). The hypervariable region (HVR) of the S1 gene was amplified by the pair, CK4 and CK2, designed by Keeler et al (28).

DNA sequence analysis

The PCR products were purified with the QIAEX II gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Ontario). Direct automated cycle sequencing was performed using an ABI 377 DNA sequencing system at the University of Guelph Molecular Supercentre. The deduced sequences were analyzed by Vector NTI (Invitrogen). Sequence data alignment was performed using the GenBank Blast server (National Centre for Biotechnology Information: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Pathogenicity study

Chickens (SPF white leghorn) of mixed gender were hatched at the Arkell Poultry Station from eggs obtained from Hy-Vac (Adel, Iowa, USA). The birds were housed at the University Isolation Unit in cages according to The Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals of the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC), and received feed (21% unmedicated starter ration) and water ad libitum. Chickens were tagged with wing bands (Ketchum Manufacturing, Brockville, Ontario) for identification and randomly divided into 5 treatment groups of 30 birds per group and 2 negative control groups, which each consisted of 20 birds. Within each treatment group 15 birds were assigned for determination of pathogenicity, while another 15 birds were assigned for assessment of weight gain over time. In the control groups, 10 birds were assigned for the pathogenicity study and 10 others were assigned for assessment of weight gain.

The pathogenicity study was conducted in 2 parts at different times: part A consisted of the assessment of 3 isolates, IBV-ON1, IBV-ON2, and IBV-ON4; part B consisted of the assessment of 2 isolates, IBV-ON3 and IBV-ON5.

At 24 days of age, the chickens were inoculated intraocularly and intranasally with 0.2 mL/per bird of undiluted virus divided equally between the routes. Birds in control groups were inoculated with 0.2 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The virus titers were as follows: IBV-ON1 isolate 105.5 EID50/mL, IBV-ON2 isolate 104.5 EID50/mL, IBV-ON3 isolate 105.7 EID50/mL, IBV-ON4 isolate 104.5 EID50/mL, and IBV-ON5 10 isolate 6.2 EID50/mL.

The birds were observed for clinical signs that included gasping, coughing, sneezing, depression, and ruffled feathers. The clinical signs were scored twice daily for 10 d according to the following formula: 0 = no signs; 1 = mild signs; and 2 = severe signs. Mild gasping, coughing, or depression were considered mild signs. Severe gasping, coughing, or depression, or both, accompanied by ruffled feathers were scored as severe signs.

Three chickens from each infected group and 2 from the negative control group were randomly selected (MINITAB 14) at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days post inoculation, euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and necropsied. Gross lesions were scored according to the criteria of McMartin (29). Selected tissues, cranial part of each trachea, left lung and kidney, were collected. Part of these tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 48 h and then embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (30). The caudal part of each trachea was collected and kept frozen at −70°C until RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

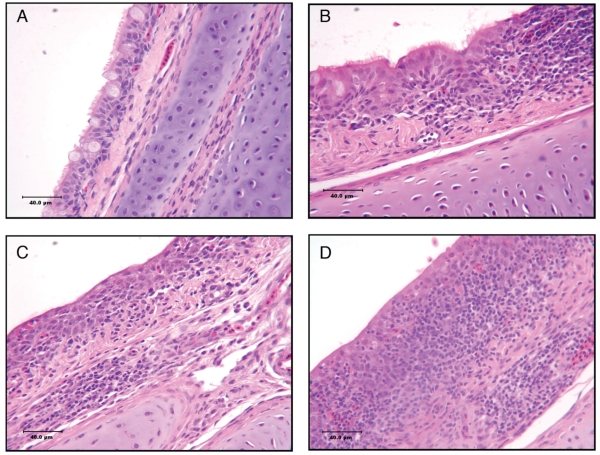

All slides were evaluated in a “blind” fashion such that the pathologist had no knowledge of the treatment groups. The histological lesions in trachea were scored based on the modified protocol of Alvarado et al (31). A score of 1 indicated no lesions. A score of 2 was mild epithelial hyperplasia and mild subepithelial lymphoid infiltration with occasional germinal centers, and mucous glands were distorted and elongated. For a score of 3, moderate epithelial hyperplasia with loss of cilia and moderate subepithelial lymphoid infiltration was seen, mucous glands were decreased in size, and there was edema of the lamina propria. A score of 4 represented extensive epithelial hyperplasia and subepithelial lymphoid infiltration, the superficial epithelial layer was flattened and had a squamous appearance, mucous glands were not detectable. The microscopic changes of the trachea illustrating the scoring system are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Microscopic changes in trachea taken from chickens infected with IBV.

A — Score 1 — no lesions;

B — Score 2 — mild epithelial hyperplasia and subepithelial lymphoid infiltrate where ciliated cells were rounded and become detached from the surface, the lamina propria infiltrated with lymphocytes and occasional germinal centre was present, mucous glands distorted and elongated;

C — Score 3 — moderate epithelial hyperplasia and subepithelial lymphoid infiltrate where complete loss of cilia was consistent with desquamation of mucous membrane, decreased number of alveolar mucous glands, and pronounced edema of the lamina propria;

D — Score 4 — severe epithelial hyperplasia and subepithelial lymphoid infiltrate with increased thickness of mucosa, superficial layer of epithelial cells become squamous and mucous glands are not detectable in this area. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Bar = 40 μm.

Fifteen birds per treatment group and 10/group for each negative control were assigned for assessment of weight gain. Each chicken was weighed weekly on the same day of the week over a period of 6 wk post inoculation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for clinical signs was as follows. The proportion of birds exhibiting any clinical sign on a daily basis was calculated for each cage. Descriptive statistical analysis of proportions was performed by examining means and standard deviations for each treatment group and graphically by plotting mean proportion for each treatment group over the study period.

Differences among the proportion of birds within groups exposed to different treatments (isolates and negative control) that showed any clinical sign throughout the study period was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Following a statistically significant result on the Kruskal-Wallis test, the Wilcoxon test was used for pair-wise comparison between treatment groups. A P-value < 0.05 was interpreted as a statistically significant result. Histological scores were analyzed with the same tests as described for the clinical lesions. Analysis of histological scores and proportion of clinical signs was performed simultaneously with part A and B because data from negative controls were identical. Descriptive statistical analysis of weight was performed by examining means and standard deviations (s) for each treatment group and graphically by plotting mean weight and standardized mean weight for each treatment group over the study period. Standardization was done by subtracting the overall mean from the mean of pullets and roosters in that group, and dividing it by the standard deviation at that weighing occasion.

Differences in weight gain of birds exposed to treatment groups (isolates and negative control) throughout the study period were tested using linear mixed effect model. Data from pathogenicity study part A and B were analyzed separately because the initial weight of birds in the negative control groups was different between parts A and B. In addition, the differences in average daily weight gain in the first 11 d post inoculation among the treatment groups was evaluated by analysis of covariance using the F-test. Following the significant F-test, expected means of birds exposed to viruses were compared with the negative controls. Analyses were adjusted for the effect of initial weight and sex.

Results

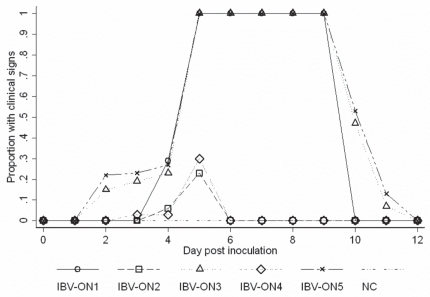

Clinical signs, gross and histological lesions, and weight gain were considered as indicators to determine the pathogenicity of 5 IB virus isolates from Ontario. Results of clinical observations are presented in Table I and Figure 2 and are briefly summarized in the following text. Sneezing and tracheal rales were observed at 2 d post inoculation in all birds infected with IBV-ON3 and IBV-ON5. Generally, tracheal rales were short in duration, while sneezing continued until day 12 post inoculation. Of the chickens infected with the IBV-ON4, 30% developed mild sneezing at 3 days post inoculation, which lasted 3 d. Chickens infected with IBV-ON1 and IBV-ON2 developed sneezing at 4 d post inoculation, and respiratory signs stopped by day 10, while, in the case of IBV-ON2 only sneezing that lasted for 2 d was noted in < 20% of the birds. Table I shows the results of a descriptive statistical analysis of the proportion of birds within each group inoculated with different isolates throughout the study period. Figure 2 depicts the mean proportion of birds that exhibited any clinical sign for each group over the study period. Differences among the proportion of birds exhibiting any clinical signs among groups of birds inoculated with different isolates and negative control birds were statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis: P < 0.01). The P-values (Wilcoxon) obtained from comparison of proportions between each treatment pairs were also determined.

Table I.

Proportion of birds that showed any clinical signs during the first 12 days after inoculation with different IBV isolates and in negative controls

| Isolate | na | Meanb | Medianb | Minimum | Maximum | s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBV-ON1 | 23 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.49 |

| IBV-ON2 | 23 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.08 |

| IBV-ON3 | 23 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.45 |

| IBV-ON4 | 23 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.09 |

| IBV-ON5 | 23 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.44 |

| NC | 23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| NC | 23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

NC — negative control; s — standard deviation.

n — the number of cages evaluated throughout study period in each treatment group. The chickens for each virus infection were in 2 cages and were observed twice each day for 12 d post inoculation. On day 12 there was only 1 observation made, and birds were then euthanized.

Mean and Median clinical scores are two measures of average clinical score in each treatment group over the entire study period. For example, 46% (or more appropriately 13%) of birds inoculated with IBV-ON1, on average, showed any clinical signs over the 12-day study period.

Figure 2.

Mean proportion of birds exhibiting any clinical signs throughout the 12-day study period after exposure to different IBV field isolates.

No gross lesions were observed in the trachea, lung, and kidney of birds in any of the groups.

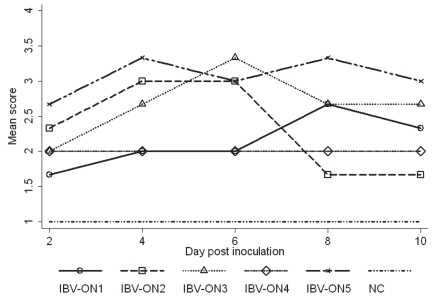

The summary of histological lesions and scores is shown in Table II and Figure 3. All 5 viruses induced typical IB lesions in the trachea, but no lesions were found in any of the lungs and kidneys examined. Characteristic IB lesions were seen in 68 out of 75 examined tracheas. Some typical lesions of the trachea are shown in Figure 1. Tracheal lesions were particularly prominent in chickens infected with isolate IBV-ON5 followed by infection with isolate IBV-ON3. Isolates IBV-ON1, IBV-ON2, and IBV-ON4 induced less prominent and generally milder tracheal lesions. Table II contains descriptive statistics of histological scores for each group. Figure 3 depicts the mean scores for histological lesions for each group over the study period. Difference in mean histological lesions among groups inoculated with different isolates was statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis: P < 0.01). The P-values (Wilcoxon) obtained from comparison of scores between treatment pairs were also determined.

Table II.

Summary of scores for histological lesions in birds exposed to different field isolates and a negative control during the first 10 days post inoculation

| Isolate | na | Meanb | Medianb | Minimum | Maximum | s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBV-ON1 | 15 | 2.13 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.52 |

| IBV-ON2 | 15 | 2.33 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.90 |

| IBV-ON3 | 15 | 2.67 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.72 |

| IBV-ON4 | 15 | 2.00 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.38 |

| IBV-ON5 | 15 | 3.07 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.80 |

| NC | 20 | 1.00 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 |

NC — negative control; s — standard deviation.

n — number of birds per group (virus isolate).

Mean and median scores are 2 measures of average histological score in each treatment group.

Figure 3.

Mean scores of histological lesions for each treatment group of birds infected with IBV throughout the first ten days of the study.

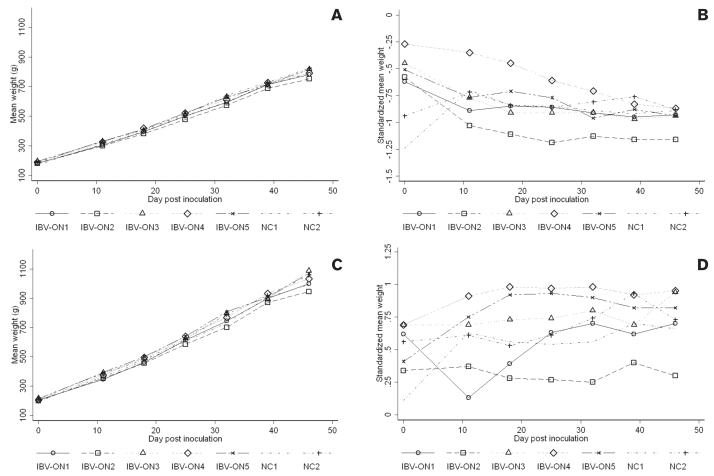

To demonstrate the effects of different virus isolates on weight gain, individual chickens were weighed weekly. Mean weights and standardized mean weight over time for pullets are depicted in Figure 4, panels A and B, respectively. Mean weights and standardized mean weights over time for roosters are depicted in Figure 4, panels C and D, respectively. The effect of virus infection on the growth of birds over the entire study period was marginally significant in part A (F-test: P < 0.09). Birds inoculated with IBV-ON2 tended to have 1.74 g/d lower weight gain than birds in the negative control group (P < 0.10). The effect of virus on the growth of birds was not statistically significant in part B (F-test: P = 0.80). The difference in average daily gain during the first 11 d post inoculation in birds inoculated with different isolates was significant in part A (P < 0.01), but not in part B (P > 0.1). Birds exposed to IBV-ON1 had 2.6 g lower average daily weight gain than birds in the control group (P < 0.01). Similarly, birds exposed to IBV-ON2 had 2.2 g lower daily weight gain than birds in the control group (P < 0.01). Birds exposed to other isolates had a lower average daily weight gain than birds in the negative control in the first 11 d post inoculation, which did not reach statistical significance at the P < 0.05 level. In part B, birds inoculated with IBV-ON3 tended to have 0.82 g lower average daily weight gain than birds in the negative control group (P = 0.08). By the end of the experiment the differences in average daily weight gain among birds inoculated with different isolates were compensated.

Figure 4.

Mean weights (A and C) and mean standardized weights (B and D) of pullets (A and B) and roosters (C and D) inoculated with Ontario IBV field isolates and in 2 negative control groups of parts A and B over the entire 46 days period of the study.

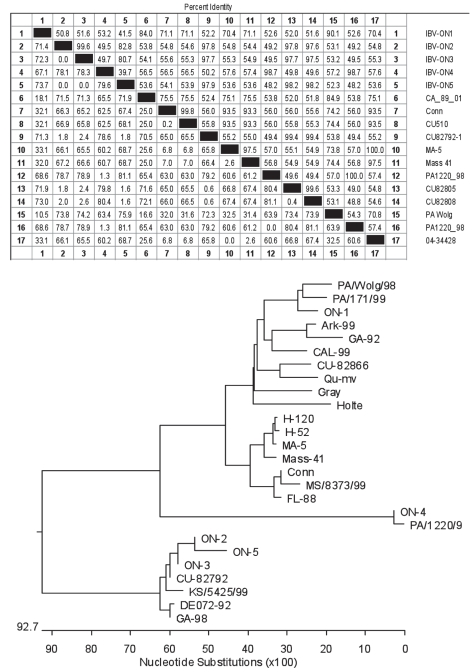

The S1 gene specific primers amplified approximately 600 bp products, which were sequenced and compared to reference and other well-characterized IBV RNAs (Figure 5). For the Ontario isolates, IBV-ON1 had the highest derived amino acid similarity (70% to 71%) to the Mass 41 reference and MILDVAC-Ma5 (Intervet) vaccine strains, while IBV-ON2 had the lowest similarity (55%) to these two. Phylogenetic analysis, shown in Figure 5B, revealed a cluster of IBV-ON2 -ON3 and -ON5 and these 3 grouped with the CU-82792 isolate; IBV-ON4 seemed to be very close to PA/1220/9. The S1 nucleotide sequences of all 5 viruses were determined before and after the animal experiment. There were no changes in the nucleotide sequences for any of the viruses despite the fact that each isolate was passaged 4 times in SPF embryonated eggs, and once in chickens during the in vivo study.

Figure 5.

Amino acid sequence percent identity and similarities (A), and phylogenetic analysis of the S1-gene specific PCR products of five Ontario IBV isolates (B).

Discussion

The results of this pathogenicity study conducted in SPF layer chickens demonstrated that the 5 Ontario field IBV isolates were mild respiratory viruses and infection with certain isolates could cause subclinical disease. Signs of reported respiratory distress (13) such as cough, nasal discharge, watery eyes, and difficulty in breathing manifested by open beak, were not noted in our trials. The observations herein agreed partially with the clinical findings of Purcell and McFerran (32) who reported moist rales within 48 h after exposure, the birds had their beaks open, and developed a cough that persisted up to 10 d. During infection, the chickens had slightly depressed food consumption. In addition, there was a slight effect on the voice of the exposed birds and during the period of reduced feed intake the birds appeared abnormally quiet. The generalized weakness accompanied by depression, as reported by Cavanagh and Naqi (12) was not seen in the birds in our experiment.

Despite the clinical signs seen, although they were mild to moderate, none of the 5 isolates induced gross lesions, and these negative postmortem findings were not consistent with the results of Purcell and McFerran (32), who found thickened and oedematous mucosa of the trachea and extrapulmonary bronchi. Furthermore, 24 h after exposure, the same authors (32) noted cloudy and edematous abdominal and posterior thoracic air sacs, which 3 d later thickened and filled with clear bubbly exudates. We did not observe any gross changes in the air sacs, which were thin, clear, and transparent. The lungs also appeared normal in all birds except for patchy congestion in a few, similar to the observations of Purcell and McFerran (32). From the 5 isolates studied, IBV-ON3 and IBV-ON5 induced the strongest respiratory distress manifested by sneezing and tracheal rales in all exposed chickens over a 12-day period post inoculation; these viruses also induced the most prominent histological lesions in the trachea. Although the histological lesions were very prominent in the trachea during the first 6–7 d after exposure to IBV-ON2, the clinical signs were mild and seen for a limited time only (Figures 2 and 3).

Based on sequence comparison, Stachowiak (23) grouped IBV-ON1, IBV-ON2, IBV-ON3, and IBV-ON5 as isolates associated with respiratory and reproductive signs, while IBV-ON4 was more closely related to nephropathogenic strains of IBV. In this study, IBV-ON4 did not induce any clinical signs, or lesions in kidneys. It induced mild lesions in trachea, which did not differ from the lesions induced by isolates classified as respiratory viruses. These findings are in accordance with some reported observations for non-SPF chickens (33,34).

One of the important findings of this study was the significantly lower average daily weight gain among chickens inoculated with the virus (for example, IBV-ON1 and IBV-ON2) suggesting the effect of virus during the acute phase of infection. A number of authors have reported the lower weight gain associated with IBV infection (12,13,35), but no studies have reported the effect of IBV infection on weight gain of birds under controlled experimental conditions and in SPF chickens. Prince et al (35) looked at the performance of healthy chickens and chickens inoculated with IBV at different temperatures and ventilation rates. Moreover, the birds in their experiment were all male White Plymouth Rock chickens, and not layers. These authors found that noninfected chicks gained approximately 69 g more per bird than those that were infected. The differences in feed consumption due to disease were significant, and the differences in weight gain, feed consumption, and feed efficiency due to disease were consistent through all experiments and at each temperature. However, the feed efficiency was not significantly affected by IBV infection or by ventilation rate. For field conditions, it would be difficult to predict if the effect of virus infection on weight gain of growing layer chickens would be temporary, as it was in our controlled study, or long-lasting.

Our data on lower average daily weight gain in birds inoculated with viruses should be interpreted with caution for the following reasons. These numbers were obtained for SPF birds that were free of other infection and were kept under optimal husbandry conditions. These conditions are unlikely in the field, where birds may be exposed to multiple pathogens simultaneously. All birds were inoculated with the virus at the same time. Although infection with IBV in a barn spreads quickly (13), it is unlikely that all birds are exposed to the virus simultaneously. Finally, although the differences were statistically significant in the first 11 d, and tended to be significant for 1 virus throughout the study period, it is still not clear whether the difference in average daily weight gain is clinically relevant or not. Birds exposed to all viral isolates had numerically lower expected average daily weight gain than birds in the control group in the first 11 d of the trial. However, this difference was statistically significant in birds exposed to IBV-ON1 and IBV-ON2 only.

Sequence analysis of part of the S1 gene indicated that none of the isolated viruses was of vaccine origin of the 2 vaccine strain type viruses (Mass and Conn) that are available and used in Ontario (Figure 5). IBV-ON2, IBV-ON3, and IBV-ON5 formed a cluster and they were closely related to strain CU-82792, which was first described in the United States and is postulated to be similar to DE/072/92 (36). IBV-ON4 had 98.7% identity with strain PA/1220/9, a nephropathogenic variant of IBV (37). These data support the suggestion that these viruses were introduced to Ontario from the USA; however, the surveillance conducted at the time of the sentinel bird placement did not reveal any information that could help in tracing the origin and spread of these field viruses (24).

The sequences of the viruses before and after their passage in embryonated eggs and chickens were also compared, and surprisingly, they all were 100% identical. Although, a similar observation was also reported by Naqi et al (38), who suggested that genetic changes might not be a constant feature of all IBV strains as it is among mammalian coronaviruses, the S-gene sequences usually show some variability upon in vitro and in vivo passages (6,10).

Future work should aim to determine if the available and used IB vaccines provide sufficient protection against these Canadian IBV isolates.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Egg Farmers of Ontario and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. This study was part of the MSc thesis of Dr. Helena Grgiæ. We thank Mr. Tony Cengija and his staff for their skilled animal care.

References

- 1.Spaan WJM, Cavanagh BD, de Groot RJ, et al. Family Coronaviridae. In: Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editors. Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. 8th Report of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego: Academic Pr; 2005. pp. 947–964. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai MM, Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boursnell ME, Brown TD, Foulds IJ, Green PF, Tomley FM, Binns MM. Completion of the sequence of the genome of the coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:57–77. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavanagh D, Davis PJ, Cook JKA, Li D, Kant A, Koch G. Location of the amino acid differences in the S1 spike glycoprotein subunit of closely related serotypes of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Pathol. 1992;21:33–43. doi: 10.1080/03079459208418816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sapats SI, Ashton F, Wright PJ, Ignjatovic J. Sequence analysis of the S1 glycoprotein of infectious bronchitis viruses: Identification of a novel genotypic group in Australia. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:413–418. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-3-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavanagh D, Picault JP, Gough R, Hess M, Mawditt K, Britton P. Variation in the spike protein of the 793/B type of infectious bronchitis virus, in the field and during alternate passage in chickens and embryonated eggs. Avian Pathol. 2005;34:20–25. doi: 10.1080/03079450400025414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusters JG, Niesters HG, Lenstra JA, Horzinek MC, van der Zeijst BA. Phylogeny of antigenic variants of avian coronavirus IBV. Virology. 1989;169:217–221. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90058-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelb J, Jr, Keeler CL, Nix WA, Rosenberger JK, Cloud SS. Antigenic and S-1 genomic characterization of the Delaware variant sero type of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Dis. 1997;41:661–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackwood MW, Hilt DA, Williams SM, Woolcock P, Cardona C, O’Connor R. Molecular and serologic characterization, pathogenicity, and protection studies with infectious bronchitis virus field isolates from California. Avian Dis. 2007;51:527–533. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086(2007)51[527:MASCPA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bochkov YA, Tosi G, Massi P, Drygin VV. Phylogenetic analysis of partial S1 and N gene sequences of infectious bronchitis virus isolates from Italy revealed genetic diversity and recombination. Virus Genes. 2007;35:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s11262-006-0037-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavanagh D. Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. Vet Res. 2007;38:281–297. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavanagh D, Naqi SA. Infectious bronchitis. In: Saif YM, editor. Disease of Poultry. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Univ Pr; 2003. pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ignjatovic J, Sapats S. Avian infectious bronchitis virus. Rev Sci Tech. 2000;19:493–503. doi: 10.20506/rst.19.2.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boltz DA, Nakai M, Bahra JM. Avian infectious bronchitis virus: A possible cause of reduced fertility in the rooster. Avian Dis. 2004;48:909–915. doi: 10.1637/7192-040808R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook JK, Chester J, Baxendale W, Greenwood N, Huggins MB, Orbell SJ. Protection of chickens against renal damage caused by a nephropathogenic infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Pathol. 2001;30:423–426. doi: 10.1080/03079450120066421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RC, Ambali AG. Re-excretion of an enterotropic infectious bronchitis virus by hens at point of lay after experimental infection at day old. Vet Rec. 1987;120:617–620. doi: 10.1136/vr.120.26.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winterfield RW, Fadly AM, Hoerr FJ. Immunity to infectious bronchitis virus from spray vaccination with derivatives of a Holland strain. Avian Dis. 1976;20:42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ignjatovic J, Galli L. The S1 glycoprotein but not the N or M proteins of avian infectious bronchitis virus induces protection in vaccinated chickens. Arch Virol. 1994;138:117–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01310043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavanagh D. Severe acute respiratory syndrome vaccine development: Experiences of vaccination against avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus. Avian Pathol. 2003;32:567–582. doi: 10.1080/03079450310001621198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nix WA, Troeber DS, Kingham BF, Keeler CL, Jr, Gelb J., Jr Emergence of subtype strains of the Arkansas serotype of infectious bronchitis virus in Delmarva broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 2000;44:568–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelb J, Jr, Wolff JB, Moran CA. Variant serotypes of infectious bronchitis virus isolated from commercial layer and broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 1991;35:82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smati R, Silim A, Guertin C, et al. Molecular characterization of three new avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) strains isolated in Quebec. Virus Genes. 2002;1:85–93. doi: 10.1023/A:1020178326531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stachowiak B. Guelph, Ontario: Univ. of Guelph; 2003. Infectious bronchitis virus surveillance in Ontario layers [MSc thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stachowiak B, Key DW, Hunton P, Gillingham S, Nagy É. Infectious bronchitis virus surveillance in Ontario commercial layer flocks. J App Poult Res. 2005;14:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelb J, Jr, Jackwood M. Infectious bronchitis. In: Swayne DE, Glisson JR, Jackwood MW, Pearson JE, Reed WM, editors. A Laboratory Manual for the Isolation and Identification of Avian Pathogens. 4. New Bolton Center, Pennsylvania: American Association of Avian Pathologists, University of Pennsylvania; 1998. pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method for estimation fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handberg KJ, Nielsen OL, Pedersen MW, Jorgensen PH. Detection and strain differentiation of infectious bronchitis virus in tracheal tissues from experimentally infected chickens by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Comparison with an immunohistochemical technique. Avian Path. 1999;28:327–335. doi: 10.1080/03079459994579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keeler CL, Jr, Reed KL, Nix WA, Gelb J., Jr Serotype identification of avian infectious bronchitis virus by RT-PCR of the peplomer (S-1) gene. Avian Dis. 1998;42:275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMartin DA. Coronaviridae. In: McFerran JB, McNulty MS, editors. Virus Infections of Birds. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers BV; 1993. pp. 249–275. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prophet EB, Mills B, Arrington JB, Sobin LH. Laboratory methods in histotechnology. Published by the American registry of pathology; Washington, DC: 199. pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarado IR, Villegas P, El-Attrache J, Brown TP. Evaluation of the protection conferred by commercial vaccines against the California 99 isolate of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Dis. 2002;47:1298–1304. doi: 10.1637/6040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purcell DA, McFerran JB. The histopathology of infectious bronchitis in the domestic fowl. Res Vet Sci. 1972;13:116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ignjatovic J, Ashton DF, Reece R, Scott P, Hooper P. Pathogenicity of Australian strains of avian infectious bronchitis virus. J Comp Pathol. 2002;126:115–123. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2001.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albassam MA, Winterfield RW, Thacker HL. Comparison of the nephropathogenicity of four strains of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Dis. 1986;30:468–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prince RP, Potter LM, Luginbuhl RE, Chomiak T. Effect of ventilation rate on the performance of chicks inoculated with infectious bronchitis virus. Poultry Sci. 1968;41:268–272. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mondal SP, Lucio-Martinez B, Naqi SA. Isolation of a novel antigenic subtype of infectious bronchitis virus serotype DE072. Avian Dis. 2001;45:1054–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kingham BF, Keeler CL, Jr, Nix WA, Ladman BS, Gelb J., Jr Identification of avian infectious bronchitis virus by direct automated cycle sequencing of the S-1 gene. Avian Dis. 2000;44:325–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naqi S, Gay K, Patalla P, Mondal S, Liu R. Establishment of persistent avian infectious bronchitis virus infection in antibody-free and antibody-positive chickens. Avian Dis. 2003;47:594–601. doi: 10.1637/6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]