Abstract

Objectives:

To develop a knowledgebase of stories illustrating the variety of roles that librarians can assume in emergency and disaster planning, preparedness, response, and recovery, the National Library of Medicine conducted an oral history project during the summer of 2007. The history aimed to describe clearly and compellingly the activities—both expected and unusual—that librarians performed during and in the aftermath of the disasters. While various types of libraries were included in interviews, the overall focus of the project was on elucidating roles for medical libraries.

Methods:

Using four broad questions as the basis for telephone and email interviews, the investigators recorded the stories of twenty-three North American librarians who responded to bombings and other acts of terrorism, earthquakes, epidemics, fires, floods, hurricanes, and tornados.

Results:

Through the process of conducting the oral history, an understanding of multiple roles for libraries in disaster response emerged. The roles fit into eight categories: institutional supporters, collection managers, information disseminators, internal planners, community supporters, government partners, educators and trainers, and information community builders.

Conclusions:

Librarians—particularly health sciences librarians—made significant contributions to preparedness and recovery activities surrounding recent disasters. Lessons learned from the oral history project increased understanding of and underscored the value of collaborative relationships between libraries and local, state, and federal disaster management agencies and organizations.

Highlights

Librarians have been largely overlooked as contributors to disaster planning, response, and recovery. Librarians have been instrumental in creating and evaluating technical tools, training emergency responders, providing information at the point of need, and rebuilding collections, institutions, and communities.

Respondents to the oral history project shared their experiences with a wide range of disaster and emergency situations, such as Hurricane Katrina, the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and the SARS outbreaks in 2003.

Implications

Findings from the oral history broadened understanding of the roles of librarians in disaster management and supported the involvement of librarians in local, state, and federal emergency management initiatives.

Future plans to publish the stories will give librarians a forum to share their disaster response experiences and provide them with the opportunity to learn from their colleagues.

Introduction

The US National Library of Medicine's (NLM's) Library Roles in Disasters Project (LRDP) evolved out of a recognition of the many roles that librarians have played in emergency and disaster planning, response, and recovery. It is difficult to ascertain, however, if librarians have recently adopted roles in community-wide disaster response or if their efforts have been longstanding. Literature addressing library disaster planning has primarily focused on collection restoration and protection efforts [1]. Prior to Hurricane Katrina, a notable exception occurred when the library community credited the efforts of public libraries acting as community crisis centers following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks [2]. Recognition in the United States grew again after the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, when researchers and reporters gradually recognized the essential functions that libraries performed in disaster response. Public libraries gained attention for helping people who needed Internet access to fill out Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) forms and other online applications or declarations [2–7]. Other reports discussed librarians' work in evacuation shelters, bringing books and needed reference materials [8,9]. Health sciences libraries and librarians also received credit for providing reference service in the aftermath of a disaster [8]. Anecdotal evidence and word of mouth, however, suggested that librarians did much more than provide reference service and help fill out forms.

By providing relief awards, NLM and the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NN/LM) supported the organized efforts of librarians and other information professionals to provide needed outreach [10–12]. Other libraries, working with emergency agencies and community groups, offered assistance services through library-run call centers and hotlines [2,9,13]. Librarians with knowledge of preservation methods rushed to the aid of other institutions to salvage damaged collections [14]. Informal discussions with NLM and NN/LM focused on stories of librarians volunteering at evacuation shelters, where they distributed books, provided reference services, and even set up entire stand-alone libraries. Other stories told of librarians quickly reestablishing services to their hospitals, universities, and communities, even after losing staff members, collections, buildings, electricity, Internet and telephone service, or plumbing. A particularly interesting story told of a public health librarian organizing information at a call center to be distributed after an epidemic outbreak. All stories had a common theme, however, of librarians acting as consummate professionals in emotionally charged situations. This combination of word-of-mouth evidence and published reports of libraries' disaster-related work prompted NLM investigators to focus their attention on publicizing librarian contributions to community disaster response through the LRDP.

Professional librarians, connected through library associations and NN/LM, had many stories to tell, and the LRDP aimed to capture these experiences. In keeping with the tradition of medical library oral histories—as established in the late 1970s by the NLM-funded Oral History Project of the Medical Library Association (MLA) [15]—the project leaders for the LRDP determined that library disaster response stories would be faithfully recorded in the words of librarians. The scope of the project was broad: interviews were conducted with academic, hospital, public, and special librarians. Professionals from other fields (nonlibrarians) were also sought for their testimonials about the contributions of libraries to disaster response. Disaster situations included bombings and other acts of terrorism, earthquakes, epidemics, fires, floods, hurricanes, and tornados.

The LRDP's purpose in gathering stories was to develop a knowledgebase of the kinds of roles librarians can assume in disaster and emergency planning, preparedness, response, and recovery. By providing eye-witness accounts of the range of traditional and nontraditional roles that librarians have played, the LRDP aimed to demonstrate the value of library and librarian involvement in local, state, and federal disaster and emergency planning and response initiatives.

Methodology

The initial phase of the LRDP involved a literature review to provide insight into the range of potential roles, the extent of investigatory work in the area of library response, and the level of sensitivity required to approach participants. Investigators ran a multi-database search of terms related to emergency management, disaster response, and libraries in MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, Library Literature & Information Science, and Library Information Science & Technology Abstracts. Web-based searches and searches of Factiva were also conducted to investigate specific disaster incidents, such as Hurricane Katrina and the SARS outbreak.

In keeping with the recommendations for selecting interviewers who have knowledge of the same area of librarianship as the interviewees, as set out in the MLA Oral History Project Manual [15], NLM investigators sought an interviewer in the form of an NLM associate fellow and encouraged her to gain background knowledge of the disaster situations before establishing contact with the interview candidates. The choice also aligned with the manual's assertion that MLA fellows make quality interviewers because of their institutional knowledge [15], and NLM associate fellows have comparable knowledge about NN/LM to the knowledge MLA fellows have about MLA. Building trust with the respondents in a short period of time became one of the biggest challenges of the LRDP; knowledge about their experiences greatly aided the interview process.

Identifying Participants

Names of potential interview candidates were collected from the literature review materials and from an initial round of interviews with key NN/LM resource people. These internally designated “NN/LM resource people,” typically medical library directors from the NN/LM South Central and Southeastern/Atlantic regions, formed a convenient group of qualified professionals with connections across the network and broad knowledge of the activities of libraries in the area. Project leaders determined that only North American stories would be recorded in the LRDP, given time constraints that made it too difficult to interview librarians across an international spectrum.

From these collection methods, more than 100 names of interview candidates were compiled in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet file. It quickly became evident, however, that the majority of potential participants were from Southern or Gulf Coast states and had stories about Hurricane Katrina. While not intending to downplay the massive impact of this devastating storm, investigators decided to select stories that would represent a wide range of disaster scenarios. Subsequently, many stories about Hurricane Katrina were not represented in the LRDP.

During the same selection period, the possibility of interviewing people who had been aided by a library or librarian was discussed. Concerns were voiced that librarians testifying to their own importance would bias the results (not present a balanced account). To counteract this possibility, contact information was also sought for “nonlibrarians.”

A group of 27 potential participants was selected from the list of over 100 potential interview candidates; however, the initial participant population expanded to 37 as a result of recommendations from the contacted individuals.

Conducting the Interviews

Investigators decided that participants would be given the choice to respond via email or telephone. Initial contact was made through an email, followed by a telephone call within one week. From the pool of thirty-seven invitees, ten participants chose to be interviewed over the telephone, nine participants selected to participate via email, and four stories were recorded using a combination of methods. The selected interviewer conducted the hour-long telephone interviews between May 31 and August 3, 2007. The majority of interviewees were asked the same four questions:

What happened in your community (i.e., what was the disaster/emergency)?

How did the library respond? How did the librarians respond? Were there nontraditional (unusual) roles that the librarians performed?

How has the library, or the services provided, changed as a result of these events?

What, in your opinion, are the roles for librarians and libraries in disaster planning, response, and recovery efforts?

The interviewer asked selected participants to reflect on their relationship with emergency agencies, organizations, or groups but only in cases where the situation suggested that such a relationship existed. Nonlibrarian respondents were asked the standard questions and typically tailored their answers to cover both their experiences working with libraries and their recommendations for future roles that librarians could fill. Aside from asking the questions and occasionally clarifying responses, the interviewer used very little prompting.

Transcribing and Compiling the Results

Email responses were edited by the interviewer for spelling and grammatical mistakes only. Every effort was made to present the stories “in the words” of their authors. The interviewer took notes of the discussion during telephone interviews and later converted the notes into a narrative. Edited transcripts were sent to participants for their approval and, in some cases, additional edits. The interviewer sent a copy of the final transcript from both email and telephone interviews to participants as well.

Once stories were recorded and edited, they were all formatted into the same document template. Key resource people and respondents were asked to provide comments about format of the final product. The majority preferred that the template showed the question before each response. No determination was reached about the style of each story, so the final set included stories written in both third and first person. Some additional files—including photographs, form documents, reports, posters, and diaries—were also received from participants. When space permitted, such files were added to the template.

Once all of the stories were finalized, the interviewer reviewed and compiled the helpful actions that were discussed in the stories, developing broad themes that encompassed the actions reported.

Providing Access to the Transcripts

While email and telephone interviews were being conducted, a website prototype was developed. Key resource people and participants recommended that the stories be made available to the public via the web. It was decided that the NN/LM website would provide a suitable home for the stories. At the time of writing, the oral history website is not yet available.

Results

In total, 37 individuals received an invitation to participate in the oral history and 23 stories were recorded, representing a high participation rate of 62%. The high number of academic health sciences librarians and hospital librarians can be attributed to the use of NN/LM contacts and the recommendations of the key resource people.

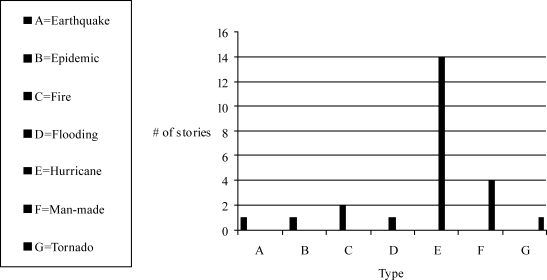

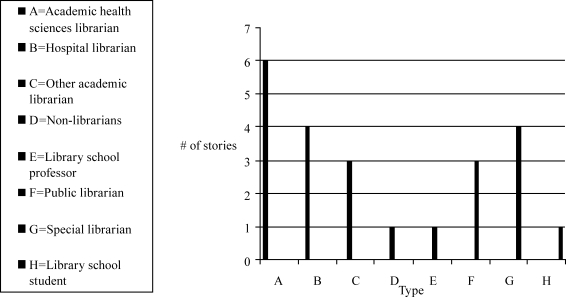

In general, the LRDP achieved its goal of representing a wide range of disaster types and library institutions. However, 14 of the 23 (61%) recorded stories were about hurricanes and 12 out of the 14 hurricane stories were about Katrina. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the breakdown of recorded stories.

Figure 1.

Stories by disaster

Figure 2.

Stories by respondent type

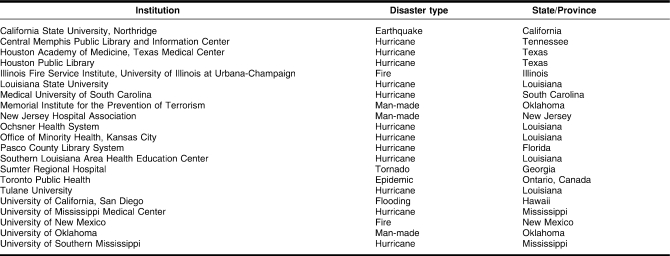

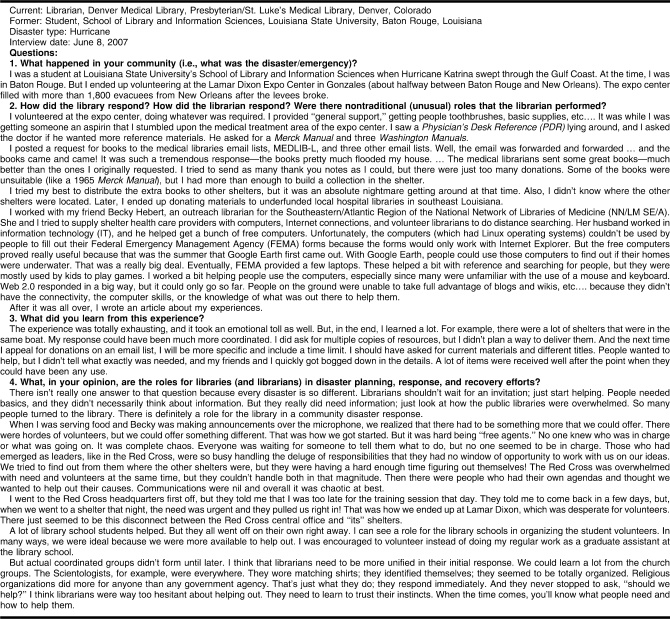

Even though the responses can be categorized, each one is unique (Table 1). Some covered emergency response strategies for saving collections. Others told of providing technical support in an evacuation shelter. And one related the terrible loss of a staff member who drowned in the rising floodwaters of New Orleans after Katrina. Some stressed the technical requirements of managing an emergency call center, while others discussed the dreadful feelings of survivor's guilt and post-traumatic stress. Figure 3 provides a sample interview.

Table 1.

Participants, disasters, and location

Figure 3.

Interview with Adelaide Fletcher

Identified Roles

All participants described numerous actions they performed in the aftermath of a disaster. These individual activities—from designing information tools for emergency responders to helping people shelter their displaced pets—yielded eight broad categories describing the librarians' roles:

Institutional supporters: This role was most frequently seen in academic libraries. Libraries acted as a command center for activities; posted institution-specific information on the web; helped displaced students and professionals (such as doctors, nurses, faculty members, and professional researchers); or acted as part of the institution-wide disaster plan.

Collection managers: The primary responsibilities of all libraries acting in this role were to protect, restore, and provide access to collections.

Information disseminators: Public, academic, special, and hospital libraries were all involved in efforts to disseminate current, reliable information to patrons, institutions, or the general public. In some cases, the library acted as the primary source of information for the entire community.

Internal planners: Librarians developed planning documents for their organizations, worked to keep track of displaced staff members, documented activities for FEMA, and generally improvised to keep their libraries running.

Community supporters: The community supporter role encompassed a number of distinct activities. Libraries acted as community gathering places; provided Internet access for evacuees; sent mobile units to shelters; volunteered wherever help was needed; gave needed emotional support; managed and dispersed donations; organized volunteers; worked in shelters; and helped people find their family members, find jobs and apartments, fill out FEMA forms, arrange for new prescription medications, locate shelters for their animals, and many other activities.

Government partners: In this role, libraries prepared reports and seminars; participated in and organized federally mandated emergency exercises; referred citizens to social service agencies; applied for grants and contracts to provide information; and worked with state health departments, local police and fire departments, and federal institutes, departments, and agencies (NLM, Environmental Protection Agency, US Department of Energy, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Commerce, and public health agencies).

Educators and trainers: Librarians trained emergency responders in the use of information tools, evaluated software, taught classes in disaster management skills, developed technology tools for emergency responders, and trained other information professionals to provide emergency reference services.

Information community builders: Libraries acting in this capacity were involved in mass book donation projects, provided restoration support to damaged sister libraries, shared information and resources via interlibrary loan and other means of electronic transfer, promoted preparedness activities, housed displaced information professionals, and established buddy systems for libraries to ensure continued services for communities.

Additional Insights

Conducting the telephone interviews proved to be an emotional experience for both the respondents and the interviewer. Participants recounted some of their most devastating experiences: death, destruction, loss, and suffering were common themes of the interviews. Some respondents told of the changes these events brought about in their lives and the strain of holding their professional lives together when their personal lives were unraveling. It became clear to the interviewer that exposure to disaster events results in long-term emotional repercussions for the responders and emergency management personnel involved.

Outcomes

An expected outcome of the project is that the stories will help NLM and other institutions support future disaster and emergency planning, response, and rebuilding efforts. Many contributors identified roles for NLM, such as providing consumer health pamphlets with information on likely infectious diseases and other health hazards that can emerge as a result of a disaster. Another suggestion was that NLM loan laptop computers to libraries struggling to serve an expanded patron population resulting from a mass evacuation in a neighboring city or state. A third request was for NLM to aid smaller libraries in their negotiations with vendors for increased access rights to electronic publications following a disaster.

Each story is interesting in its own right, but the stories also provide useful information as a set. The categories mentioned above illustrate not only the roles that libraries can play, but also some of the information needs that were not addressed before and after a disaster. Knowing what was needed can help emergency planners address those gaps in organized response efforts.

Further, the oral history format of the interview worked effectively to uncover new and surprising themes, such as the emotional strain of providing help. An understanding of the emotional toll that disaster response exerted on information professionals was absent from the published literature. The LRDP illustrated the roles of librarians, but it also exceeded expectations by providing insight into both unaddressed needs and unacknowledged stresses.

Discussion and Future Plans

Limitations

While the LRDP was not intended to be a comprehensive survey, but rather a record of a range of representative stories to help identify roles, particularly for medical libraries, it was nonetheless subject to several limitations. The process of recording the stories, using note taking versus recording and transcribing, likely decreased the degree of accuracy in the finalized transcripts. Even though respondents had an opportunity to edit transcripts, some data might not have been captured. Respondents were also remembering events that might have happened years earlier, opening the possibility for recall bias. Despite these limitations, the project yielded a useful snapshot describing library roles in various disaster situations.

Future Work

Immediate plans for the story transcripts include publishing a website based on the prototype developed during the initial project phases. The website will provide access to the stories based on geographic region, institution, and disaster type. Limited time and resources resulted in a small sample for the LRDP. The twenty-three stories illustrated common roles played by librarians, but they failed to represent the entire field of library disaster response. Future plans for the LRDP include expansion efforts to add more stories, including international stories. Web 2.0 technologies—such as blogs and wikis—have been discussed by investigators as possible tools to allow librarians to upload their own stories to the website once it is fully developed. Other plans include exploring long-term preservation of the digital transcripts.

Conclusion

Analysis of the story transcripts indicated that librarians' abilities to evaluate, organize, and disseminate accurate information made them ideal partners for emergency planners and disaster response agencies. The eight major outlined roles illustrate the versatile application of library skills in both traditional and nontraditional contexts. The stories also suggested, however, that library involvement with emergency response operations was rarely formalized. Librarians' skills were often recognized in the midst of the action—as in the case after September 11, when a librarian was called on to create a database to identify the victims, or during the SARS epidemic, when a librarian from Toronto Public Health was recruited to organize the information binders being distributed to public health nurses at the emergency call center.

Firsthand narratives from the LRDP revealed that individuals with library education and training were identified as the ideal professionals to deal with information overload. Libraries were described as being centrally located, public gathering places with well-established communication networks that regularly share information. The testimonials also indicated that librarians were willing and eager collaborators who possessed community connections, technology skills, and the right combination of sensitivity and detachment to function effectively in stressful situations. Further, the physical network of public, academic, and special libraries served as a model for local and regional command centers.

Preliminary gathering of oral histories for the LRDP built on recent growth in the field of research surrounding community-wide library disaster response. The story transcripts further provided narrative evidence of the contributions librarians have made to the field of emergency management. Recognizing the work of librarians through research is only the first step in forging fruitful partnerships. The LRDP aims to stimulate discussion and continue the work of formalizing and strengthening the collaboration between the library and emergency management communities.

Acknowledgments

The phrase, “team effort,” cannot begin to describe the level of collaboration achieved on this project. A collection of key resource people provided insight into disaster situations and guidance for approaching participants. The key resource people for this project were: Renée Bougard, Janice Kelly, Ethel Madden, AHIP, Ada Seltzer, AHIP, FMLA, and Clinton Marty Thompson Jr., AHIP. Some of the respondents who generously offered to share their stories with NLM were: Thomas Basler, FMLA, Michelle Brewer, Helen Caruso, AHIP, Susan Curzon, Kay Due, Elizabeth Eaton, Sandy Farmer, Adelaide Fletcher, AHIP, Bruce Gardham, Adam Groves, Deborah Halsted, Claudia LeSueur, Ethel Madden, AHIP, Julie Page, W. D. Postell Jr., Diane Richardson, Brad Robison, Terri Romberger, Lian Ruan, Ada Seltzer, Joyce Shaw, Clinton Marty Thompson Jr., and Fran Wilkinson. All respondents deserve credit for the success of the project, as well as the terrific support network of professionals at NLM.

Specifically, Martha Szczur and Stacey Arnesen offered suggestions, background materials, and useful contact information. Jennifer R. Heiland provided expert advice that greatly improved the website prototype. And, as always, Barbara Rapp skillfully guided the project's progress.

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by an appointment to the NLM Associate Fellowship Program, sponsored by the National Library of Medicine and administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education.

Based on a presentation at MLA ′08, the 108th Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association; Chicago, IL; May 18, 2008.

Contributor Information

Robin M. Featherstone, Associate Fellow, National Library of Medicine, Yale University, 333 Cedar Street P.O. Box 208014, New Haven, CT 06520-8014 robin.featherstone@yale.edu.

Becky J. Lyon, Deputy Associate Director Library Operations blyon@nlm.nih.gov.

Angela B. Ruffin, Head, National Network of the Libraries of Medicine; National Library of Medicine, 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20894 angela_ruffin@nlm.nih.gov.

References

- 1.McKnight M., Zach L. Choices in chaos: designing research into librarians' information services improvised during a variety of community-wide disasters in order to produce evidence-based training materials for librarians. Edmonton, AB, Canada: EBLIP. 2007;2(3):50–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Will B.H. The public library as community crisis center. Harlan, IA: Library Journal.com [Internet]; 2001. [rev. 24 May 2007; cited 28 May 2007]. < http://www.libraryjournal.com/article/CA185136.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertot J.C., Jaeger P.T., Langa L.A., McClure C.R. Public access computing and Internet access in public libraries: the role of public libraries in e-government and emergency situations [Internet] Chicago, IL: First Monday; 2006. [rev. 5 Apr 2007; cited 14 May 2007]. < http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue11_9/bertot/>. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertot J.C., Jaeger P.T., Langa L.A., McClure C.R. Drafted: I want you to deliver e-government. Harlan, IA: Library Journal.com [Internet]; 2006. [rev. 7 Apr 2007; cited 3 May 2007]. < http://www.libraryjournal.com/article/CA6359866.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block M., Kim A. All (librarian) hands on deck. Harlan, IA: Library Journal.com [Internet]; 2006. [rev. 7 Apr 2007; cited 15 May 2007]. < http://www.libraryjournal.com/article/CA6312522.html>. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Hurricane Assessment Project: final report. Atlanta, GA: Solinet; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Information Use Management and Policy Institute, College of Information, Florida State University. The 2004 and 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes: evolving roles and lessons learned for public libraries in disaster preparedness and community services, report. Tallahassee, FL: The University; c 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKnight M. Health sciences librarians' reference services during a disaster: more than collection protection. Med Ref Serv Q. 2006;25(3):1–12. doi: 10.1300/J115v25n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perlman E. Critical connectors [Internet] Washington, DC: Governing.com; 2006. [rev. 10 May 2007; cited 16 May 2007]. < http://www.governing.com/archive/2006/dec/techtalk.txt>. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Network of the Libraries of Medicine. Emergency preparedness, slideshow presentation handout. Regional Medical Library Directors' Mid-Year Meeting. 2006.

- 11.National Network of the Libraries of Medicine. Lessons learned by the NN/LM South Central Region, slideshow presentation handout. Regional Medical Library Directors' Mid-Year Meeting. 2006.

- 12.Library Operations, National Library of Medicine. Emergency/disaster preparedness, management & response: library operations and the NN/LM, slideshow presentation handout. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toronto Public Health. Hotline information liaison & co-ordination officer report. Toronto, ON: City of Toronto; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ploth D.W. Hurricanes: a learning experience. Am J Med Sci. 2006 Nov;332(5):243–4. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200611000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oral History Committee, Medical Library Association. The Medical Library Association Oral History Project manual [Internet] Chicago, IL: The Association [rev. 5 May 2007; cited 2008 Apr 17]; < http://www.mlanet.org/about/history/oral_history.html>. [Google Scholar]