Abstract

Tumor cell migration is considered as a major event in the metastatic cascade. Here we examined the effect of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on migration capacity and molecular mechanism using 4T1 murine mammary cancer cells as a model. Using an in vitro migration assay, we found that treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG resulted in concentration-dependent inhibition of migration of these cells. The migration capacity of cells was reduced in presence of NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase. EGCG suppressed the elevated levels of endogenous NO/NOS in 4T1 cells and blocked the migration promoting capacity of L-arginine. Treatment with guanylate cyclase inhibitor 1-H-[1,2,4]oxadiaxolo[4,3-a]quinolalin-1-one (ODQ) reduced the migration of 4T1 cells. EGCG reduced the elevated levels of cGMP in cancer cells and blocked the migration restoring activity of 8-Br cGMP (cGMP analogue). These results indicate for the first time that EGCG inhibits mammary cancer cell migration through the inhibition of NO/NOS and guanylate cyclase.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, guanylate cyclase, cancer cell migration, nitric oxide synthase

Introduction

Breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women in the United States and world-wide [1,2]. Metastatic spread of cancer continues to be the greatest barrier to cancer cure. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of metastasis is crucial for the design and effective clinical use of novel therapeutic strategies to combat metastasis. Tumor cell migration is considered as a major event in the metastatic cascade. Breast cancer is one of the few cancers that have several active modalities available for its treatment such as surgery, hormone therapy, cytotoxic therapy, and radiation therapy [3]. However, all these modalities are in vain in advanced stages, where metastasis has already been set and the median survival time in most conditions is not more than 2–3 years [3].

Nitric oxide (NO), an inorganic free radical gas, is synthesized from the amino acid L-arginine by a group of enzymes, the nitric oxide synthases (NOS) [4]. The production of NO at low levels is an important mediator of physiological functions such as vasodilation, inhibition of platelet aggrevation, smooth muscle relaxation and regulation of neurotransmission [4–6]. Higher levels of NO can mediate antibacterial and antitumor functions; however, chronic and sustained production of NO contributes to many pathological conditions, including inflammation-associated tissue injury and development of cancers [6–8]. The role of NO in tumor biology has been extensively studied; studies have suggested a positive association between NO and tumor progression [9,10]. It has been shown that NO promotes tumor cell migration, and tumor cell migration requires activation of nitric oxide synthase and a positive association between eNOS (endothelial-specific NOS) expression in tumor cells and growth and metastasis of tumors [9].

Phytochemicals offer promising new options for the development of more effective chemotherapeutic strategies for cancer risk and its metastasis. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is an active and major constituent of green tea and has been shown to possess anticarcinogenic properties [11]. Epidemiological studies have indicated that consumption of green tea reduces risk of many cancers, including stomach, lung, colon, rectum, liver, breast and pancreas etc. [11, 12]. In this study, we assessed the chemotherapeutic effects of EGCG on the migration of murine mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells, as the migration of cancer cells is a major event in metastatic cascade of cancers. Mouse mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells have been employed to examine the therapeutic efficacy and molecular mechanism of chemotherapeutic agents which are relevant to humans [13, 14]. The 4T1 cells are poorly immunogenic and exhibit characteristics that resemble those of stage IV breast cancer in humans [15, 16]. Here, we characterize the role of NO on the migration of mammary cancer cells and ascertained whether EGCG has any suppressive effects on NO-mediated migration of tumor cells. Thus, we present the evidence that EGCG inhibits mammary cancer cell migration and that they do so through a reduction in the production of endogenous NO by tumor cells, and that this involves the down-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) in the cell culture model used in these experiments.

Materials and methods

Chemicals, reagents and antibodies

EGCG (>98% purified) was obtained from Mitsui Norin Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), D-NAME (inactive enantiomer of L-NAME), L-arginine and 1H-[1,2,4] oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1one (ODQ), an inhibitor of guanylate cyclase, and cyclic GMP EIA Kit were obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). The 8-bromoguanosine 3’5’-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br cGMP), cGMP analogue, was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Boyden Chambers and polycarbonate membranes (8 µm pore size) for migration assays were obtained from Neuroprobe, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD).

Cells and cell culture conditions

The 4T1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Maryland) and cultured in monolayers in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 100 µg/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and maintained in humidified incubator at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

MTT assay for cell proliferation/survival

The effect of EGCG on the proliferative capacity of 4T1 cells was determined using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as described previously [17].

Migration assay

The migratory capacity of 4T1 cells was determined in vitro using Boyden Chambers (Gaithersburg, MD) in which two chambers were separated with Millipore membranes (6.5 mm filters, 8 µM pore size). Briefly, tumor cells (1.5 × 104 cells/100 µl serum-reduced medium) were placed in the upper chamber of Boyden chambers, test agents were added alone or in combination, to the upper (100 µl), and the lower chamber contained the medium alone (800 µl). Chambers were kept in an incubator for 24 or 48 h. After incubation, cells from the upper surface of Millipore membranes were completely removed with gentle swabbing; the migrant cells on the lower surface of membranes were fixed and stained using hematoxylin. Membranes were then washed with distilled water and mounted onto glass slides, examined microscopically and cellular migration was determined by counting the number of stained cells on membranes in at least 5 randomly selected fields. Migration experiment was repeated at least three times.

Immunofluorescent detection of eNOS

4T1 cells were treated with EGCG (0, 20, 40 and 60 µg/ml) for 24 h. The cells were then harvested and processed for cytospin preparation (1×105 cells/slide). Cells were fixed with methanol at −20°C for 10 min. The cells were then incubated for 30 min with 2% goat serum and 1% BSA in PBS. The slides were incubated with Alexa fluor-conjugated eNOS-specific antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were washed with PBS and eNOS-specific staining was observed under fluorescence microscope.

Assay for nitric oxide

Cell culture media were collected from cells treated identically to those used in the migration assays and stored at −20°C until assayed. The levels of NO in cell culture supernatants were measured by determining the levels of their stable degradation products, nitrate and nitrite, using a colorimetric Nitric Oxide Assay Kit (Oxford Biomedical Research, Inc., Oxford, MI) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In this method, nitrate is enzymatically converted into nitrite by the enzyme nitrate reductase and the nitrite quantified using Griess reagent.

Preparation of cell lysates and western blot analysis

Following treatment of 4T1 cells with or without EGCG, the cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS and lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. The lysate samples were subjected to western blot analysis to evaluate the levels of NOS protein, as detailed previously [17]. To ensure equal protein loading, the membrane was then stripped and reprobed with anti-β actin antibody.

Statistical analysis

For migration assays, control and EGCG or other agents-treatment groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). All quantitative data are shown as mean ± SD. In each case p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

EGCG inhibits the migration of highly metastatic murine mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells through the inhibition of nitric oxide production

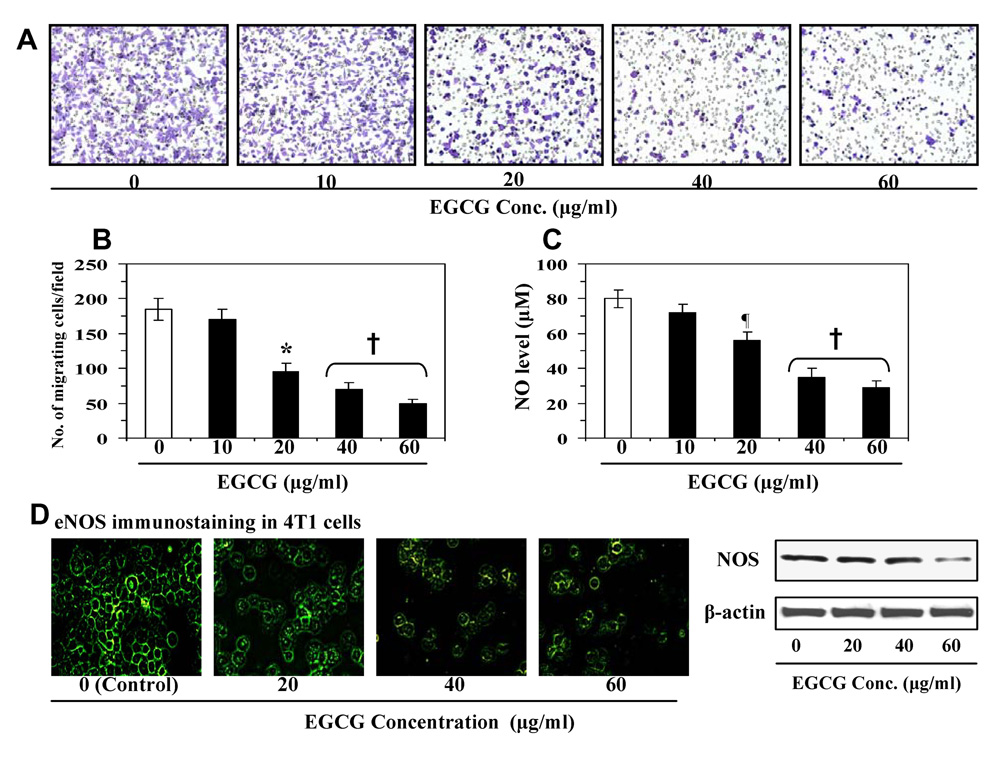

We determined whether treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG inhibits the migration of these cancer cells. For instance, we performed preliminary screening experiments to determine the effect of lower concentrations of EGCG (µg/ml) on mammary cancer cells. The selection of lower concentrations of EGCG was based on the consideration of their relevance and achievability in an in vivo system. Figure 1 showed the migration of these cells treated with various concentrations of EGCG. Relative to untreated control cells, treatment with EGCG (10, 20, 40 and 60 µg/ml) reduced the migration of 4T1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A). The numbers of migrating cells/microscopic field are summarized in Figure 1B. The results from this experiment indicated that the migration of 4T1 cells was inhibited by 8±2 to 73 ±7% (p<0.01-0.001) in a concentration-dependent manner after treatment with EGCG for 24 h. Higher inhibitory effect of EGCG was observed at the 48 h time point compared to 24 h time point. To determine whether this inhibitory effect on the migration of 4T1 cells was due to inhibition of nitric oxide production by EGCG, we determined the levels of NO in cell supernatants of the various treatment groups. We found that the treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG (10–60 µg/ml) resulted in reduction of the levels of NO production in a concentration-dependent manner compared to non-EGCG-treated control cells (Fig. 1C). As the levels of NO were decreased after EGCG treatment, we determined whether the levels of NOS were reduced in the EGCG-treated cells. The endogenous levels of eNOS were detected using immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1D), which showed that the treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG decreases the expression of eNOS in these cells. These results were further verified using western blot analysis which revealed that treatment of EGCG resulted in inhibition of NOS expression in 4T1 cells (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Treatment of murine mammary cancer 4T1 cells with EGCG for 24 h inhibits migration of cells in a concentration-dependent manner. (B) The number of migrating cells was counted and the results are expressed as a mean number of migratory cells ± SD/microscopic field. (C) Effect of EGCG on the endogenous basal level of NOS. The levels of nitric oxide were determined in cell supernatants. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of eNOS after the treatment of 4T1 cells with and without EGCG. Representative pictures are shown from two independent experiments. The levels of NOS expression were determined in cell lysates using western blotting. Significant inhibition by EGCG vs non-EGCG-treated controls, ¶p<0.05; *p<0.01; †p<0.001

To determine whether the inhibition of cancer cell migration by EGCG is due to effects of the EGCG on cell survival rather than a direct effect on migration, MTT cell proliferation/survival assays were performed using identical conditions as were used in migration assays. Treatment of 4T1 cells with various concentrations of EGCG (10–60 µg/ml) for 24 h had no effect on 4T1 cell proliferation/survival. An inhibitory effect of EGCG on cell proliferation was observed at 48 h after treatment. Based on this observation, all experiments were performed using a 24 h time point.

L-NAME inhibits 4T1 cell migration

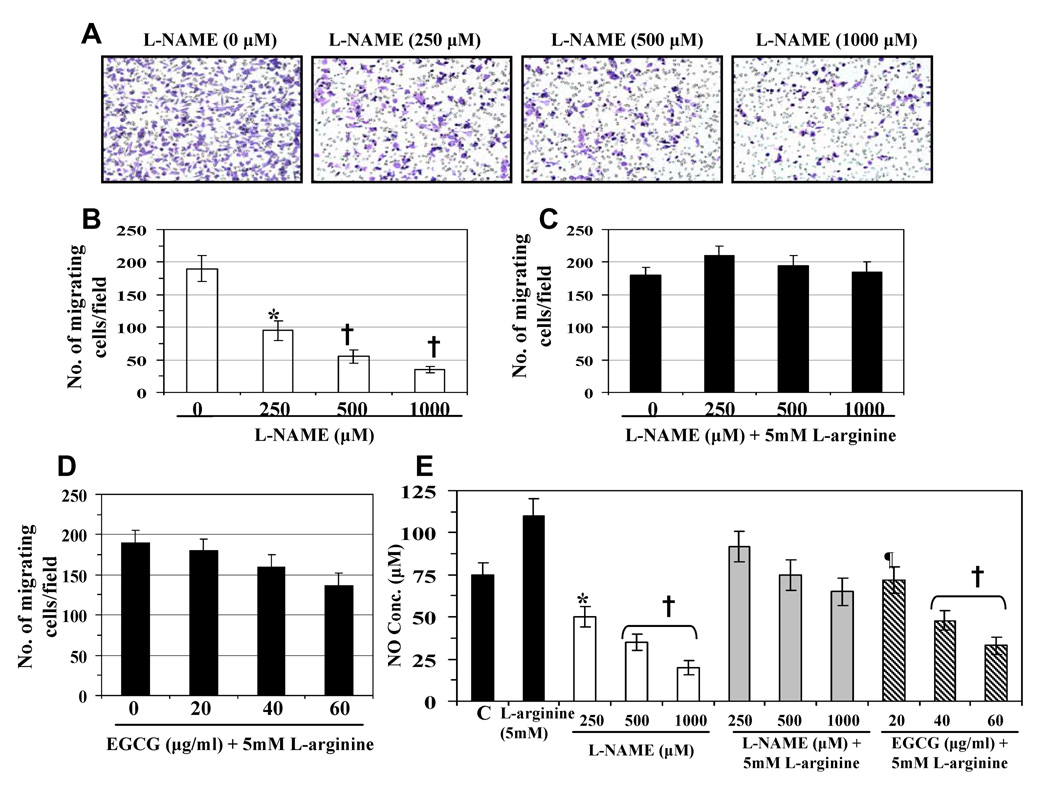

As L-NAME is a well known inhibitor of NOS, and thus, of NO production, we first determined whether L-NAME inhibited the migratory capacity of 4T1 cells. Using migration assay, we found that the treatment of 4T1 cells with L-NAME (250, 500 and 1000 µM) for 24 h resulted in a significant inhibition of cell migration in a concentration-dependent manner (50±5-82±7%, p<0.01-0.001), as compared to non-L-NAME-treated control cells (Fig. 2A). Resultant data on number of migrating cells/microscopic field from three independent experiments are summarized as means ±SD (Fig. 2B). In another experiment, the cells were treated with L-NAME with excess amount of L-arginine (a NOS substrate) for 24 h. It was observed that the inhibition of cell migration caused by L-NAME was not only blocked in the presence of additional excess of L-arginine but that the migration of 4T1 cells was slightly increased as compared with untreated control cells (Fig. 2C). Treatment of the cells with D-NAME (an inactive enantiomer of L-NAME) did not reduce the nitric oxide production in 4T1 cells and did not inhibit the migration of 4T1 cells (data not shown). These data suggest that endogenous production of NO in cancer cells plays a role in promoting the migration of 4T1 cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of L-NAME or their combinations with other agents on cell migration and NO production. (A) Treatment of 4T1 cells with L-NAME (250–1000 µM) for 24 h inhibits migration of 4T1 cells. (B) The numbers of cell migration/microscopic field are summarized as means ± SD from three independent experiments. (C) Treatment of excess L-arginine (5mM), a NOS substrate, restored the migration of L-NAME-treated cells. (D) Inhibitory effect of EGCG (20–60 µg/ml) on cell migratory capacity is blocked after 24 h treatment in presence of L-arginine. (E) L-NAME inhibits the production of NO by 4T1 cells in a dose-dependent manner, but lost the inhibitory effect on NO production in the presence of excess L-arginine. EGCG inhibits the production of NO in 4T1 cells in the presence of excess L-arginine. C= Untreated control. Significant inhibition versus control cells, ¶p<0.05; *p<0.01; †p<0.001.

Next, we analyzed the effect of L-arginine on the EGCG-induced inhibition of cell migration. Treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG (20, 40 and 60 µg/ml) with an excess amount of L-arginine (5 mM) for 24 h resulted in blockade of EGCG-induced inhibition of migration of cells in the presence of L-arginine-stimulated NO production (Fig. 2D). This additional information suggests that the inhibition of 4T1 cell migration by EGCG is mediated through the inhibition of NO production. The levels of NO release in cell supernatants from the treatment groups of these experiments (Fig. 2A, 2C and 2D) were determined and summarized in Fig. 2E.

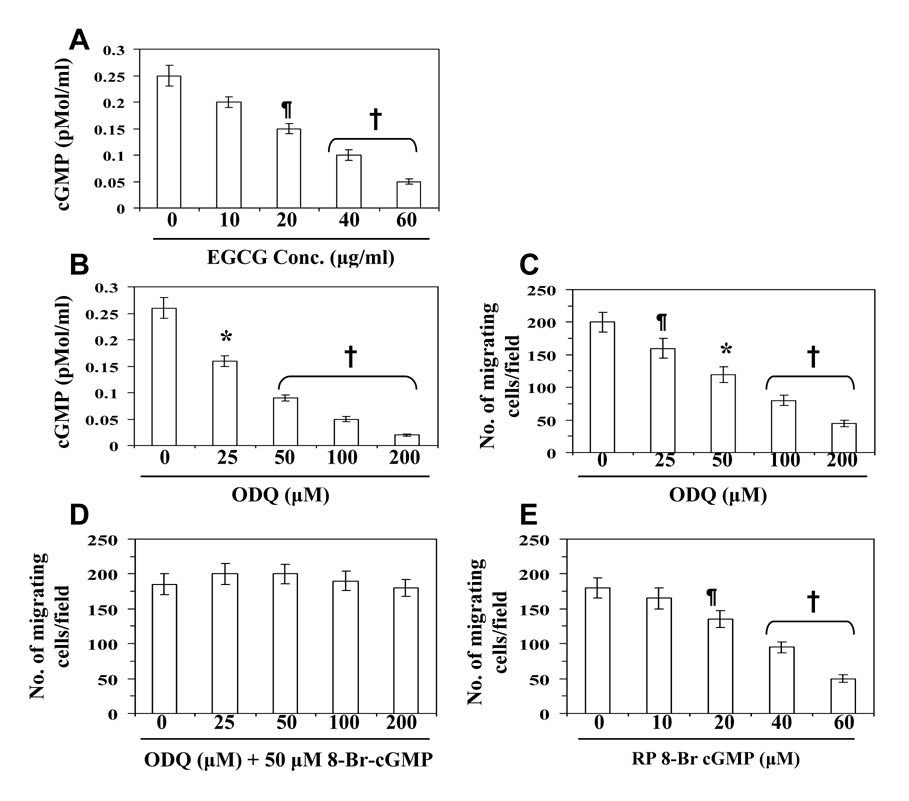

EGCG reduces the levels of cGMP in 4T1 cells: Role of cGMP modulators on cell migration

Nitric oxide has been shown to stimulate guanylate cyclase/cGMP pathway in a variety of cells [18]. Therefore, we examined whether EGCG modulates the levels of cGMP in highly metastatic 4T1 cells. The treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG (10, 20, 40 and 60 µg/ml) resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in the levels of cGMP (20±3-80±6%, Fig. 3A). To examine whether cGMP also play a role in inhibition of cell migration by EGCG, we used agents which are known to block cGMP formation (e.g., ODQ, a guanylate cyclase inhibitor), mimic cGMP action (8-Br cGMP, a cells permeable cGMP analogue), or antagonize cGMP action by inhibition of protein kinase G (RP-8-Br cGMP, a cGMP antagonist). As shown in Figure 3B, treatment of cells with ODQ resulted in a reduction in the levels of cGMP in the cell supernatants similar to that observed on treatment of the cells with EGCG (Fig. 3A). Treatment of 4T1 cells with ODQ (25–200 µM) also resulted in a significant dose-dependent inhibition of the migration of cells (20–77%, p<0.05-0.001) (Fig. 3C). Moreover, treatment with 8-Br cGMP not only blocked ODQ-induced inhibition of cell migration but also increased (insignificantly) the numbers of migrating cells (Fig. 3D) under identical conditions, suggesting a role for cGMP in mammary cancer cell migration. The migration of ODQ-treated cells that were additionally exposed to 8-Br cGMP (Fig. 3D), reached control levels, suggesting ODQ selectivity for guanylate cyclase. Treatment with RP 8-Br cGMP reduced the 4T1 cell’s migration relative to untreated control cells (Fig. 3E), further attesting to a cGMP requirement for 4T1 cell migration and the role of cGMP in EGCG-mediated inhibition of cancer cell migration.

Figure 3.

Effect of EGCG and ODQ on the basal levels of cGMP in 4T1 cells. (A) Treatment of cells with EGCG (10–60 µg/ml) for 24 h decreases the levels of cGMP in a concentration-dependent manner. (B) Treatment of cells with ODQ, an inhibitor of guanylate cyclase, decreases the level of cGMP. (C) Treatment of cells with ODQ (25–200 µM) inhibits migration of 4T1 cells in a dose-dependent manner. (D) Treatment of 8-Br cGMP, an analogue of cGMP, restored the migration of ODQ-treated cells. (E) Treatment of cells with RP 8-Br cGMP, an antagonist of cGMP, inhibits the migratory capacity of cells. Significant difference versus untreated controls, ¶p<0.05; *p<0.01; †p<0.001

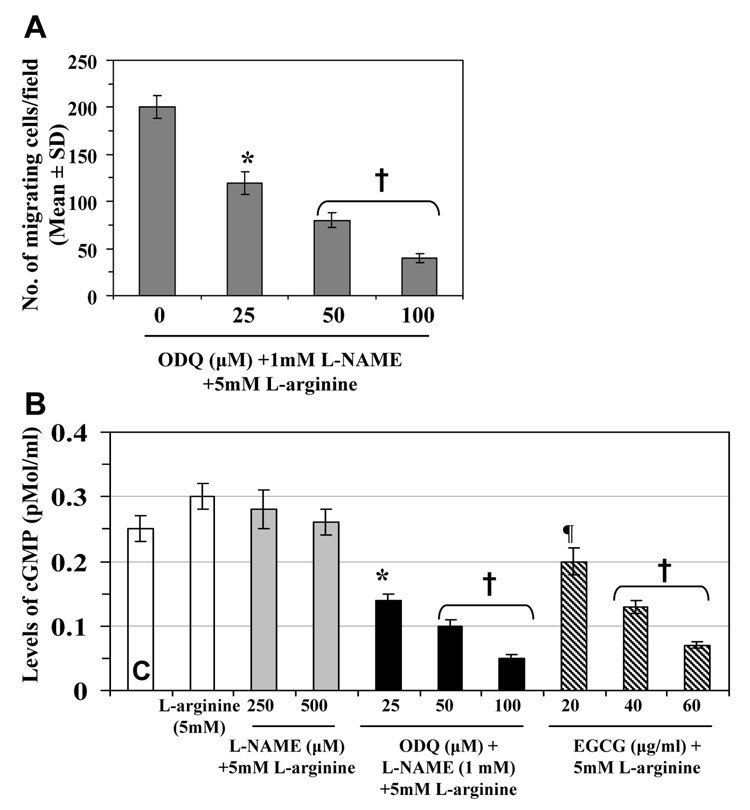

Effects of cGMP modulators on 4T1 cell migration are NO-dependent

We further examined whether endogenous NO-mediated migration of 4T1 cells requires cGMP. L-NAME was used to block NO production, L-NAME plus a molar excess of L-arginine was used to restore NO production by countering NOS inhibition. The 4T1 cells were treated with ODQ to block guanylate cyclase. The presence of ODQ blocked the migration-restoring effects of L-arginine on L-NAME-treated cells (Fig. 4A), suggesting that endogenous NO-mediated migration of 4T1 cells require cGMP. Measurement of the levels of cGMP in the different treatment groups indicated that L-arginine enhances the levels of cGMP, while excess amounts of L-arginine restore the levels of cGMP in L-NAME treated cells, as shown in Fig. 4B. Treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG inhibited the levels of cGMP in L-arginine-treated 4T1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). Together, these data suggest that EGCG-induced inhibition of mammary cancer cell migration is mediated, at least in part, through the inhibition of cGMP levels.

Figure 4.

The effect of cGMP modulators on 4T1 cells. (A) ODQ inhibits the migration restoring capacity of L-arginine in 4T1 cells. (B) Effects of cGMP modulators in combination with other agents on the levels of cGMP. The levels of cGMP in the culture media of 4T1 cells were measured using Cyclic GMP EIA Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cell culture media were used to determine the levels of cGMP. Treatment with 5mM L-arginine elevated the levels of cGMP in both untreated and L-NAME-treated 4T1 cells. Treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG (20–60 µg/ml) and ODQ blocked L-arginine-induced elevation of cGMP level in a dose-dependent manner. C= untreated control.

Significant inhibition versus untreated controls, ¶p<0.05; *p<0.01; †p<0.001

Discussion

Endogenous NO promotes tumor progression and metastasis through multiple mechanisms: such as, stimulation of tumor cell migration [18], invasiveness and tumor angiogenesis [19]. Here we have determined: (i) the role of NO in highly metastatic-specific 4T1 mouse mammary cancer cell migration and (ii) the effects of EGCG, a most active constituent of green tea, on the migration ability of these cancer cells. Our present report is the first to document the chemotherapeutic potential of EGCG on 4T1 cancer cell migration, and sequential inhibitory effect on nitric oxide synthase and guanylate cyclase pathways.

Our study reveals that the inhibition of cancer cell migration by EGCG is mediated through the reduction in the levels of endogenous NO level in 4T1 cells. The reduction in NO levels by EGCG is caused by the inhibition of NOS expression in cells. NO-mediated migration was blocked by the use of L-NAME, and this function was restored with the presence of excess L-arginine, validating the NO-mediated stimulation of tumor cell migration and demonstrating that the migration-inhibitory effects of L-NAME are NO-specific. It has been shown that NO activates soluble guanylate cyclase and elevates cGMP, which may mediate the biologic responses of NO via activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase or by modulating the phosphodiesterase activity [20, 21]. In our study, three independent criteria provided evidence that NO-mediated stimulation of mammary cancer cell migration is cGMP-dependent. First, the cGMP analogue, 8-Br cGMP, mimicked the migration-promoting role of NO, and RP-8-Br cGMP, a cGMP antagonist, had migration inhibitory effects. Second, a selective inhibitor of soluble guanylate cyclase, ODQ, inhibited 4T1 cell migration; however, this inhibition was restored with additional treatment with 8-Br cGMP, attesting to guanylate cyclase selectivity of ODQ in the migration-inhibitory response. Third, the treatment of cells with ODQ blocked the migration-restoring effect of L-arginine on L-NAME-treated cells, suggesting a requirement for cGMP in endogenous NO-mediated 4T1 cell migration. Similar to above mentioned evidences, the treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG inhibits L-arginine stimulated migration of cancer cells, and it is mediated through a reduction in NO production. Under identical experimental conditions, treatment of 4T1 cells with EGCG reduces the endogenous basal levels of cGMP similar to the effect of ODQ in this cell culture system. These observations support the evidence that inhibition of cancer cell migration by EGCG requires the inhibition of cGMP.

Overexpression of NOS enzyme by tumor cells was positively associated with the degree of malignancy of mammary tumors [22, 23]. The results obtained in our study show the chemotherapeutic potential of EGCG against mammary cancer cells which is supported by the evidences that EGCG inhibits the migration of cancer cells, an important event of tumor invasion and metastasis, through the inhibition of NO production, NOS expression and cGMP levels.

In conclusion, our study has identified for the first time that EGCG inhibits the migration of mammary cancer cells through the inhibitory effect on NO production, and successively down-regulate the migration-promoting signals induced by NO in 4T1 cells. The current new information may have relevance for developing EGCG as a novel chemotherapeutic agent alone or in combination with other anti-metastatic drugs for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer risk.

Acknowledgments

Partial financial support from NIH (R01 CA129415).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali SM, Harvey HA, Lipton A. Metastatic breast cancer: overview of treatment. Clin. Orthop. 2003;415S:S132–S137. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000092981.12414.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncada S, Higgs EA. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem. J. 1994;298:249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lala PK, Chakraborty C. Role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis and tumour progression. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:149–156. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkins DC, Charles IG, Thomsen LL, Moss DW, Holmes LS, Baylis SA, Rhodes P, Westmore K, Emson PC, Moncada S. Roles of nitric oxide in tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1995;92:4392–4396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo O, Masini E, Morbidelli L, Franchi A, Fini-Storchi I, Vergari WA, Ziche M. Role of nitric oxide in angiogenesis and tumor progression in head and neck cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998;90:587–596. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lala PK, Orucevic A. Role of nitric oxide in tumor progression: lessons from experimental tumors. Cancer Metast. Rev. 1998;17:91–106. doi: 10.1023/a:1005960822365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomsen LL, Miles DW. Role of nitric oxide in tumor progression: lessons from human tumors. Cancer Metast. Rev. 1998;17:107–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005912906436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katiyar SK, Mukhtar H. Tea consumption and cancer. In: Simopoulos AP, editor. World Rev. Nutr. And Diet. vol. 79. Basel: Karger; 1996. pp. 154–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katiyar SK, Mukhtar H. Tea in chemoprevention of cancer: Epidemiologic and experimental studies. Int. J. Oncol. 1996;8:221–238. doi: 10.3892/ijo.8.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Mohammad RM, Werdell J, Shekhar PV. p53 and protein kinase C independent induction of growth arrest and apoptosis by bryostatin 1 in a highly metastatic mammary epithelial cell line: In vitro versus in vivo activity. Int. J. Mol. Med. 1998;1:915–923. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.6.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bove K, Lincoln DW, Tsan MF. Effect of resveratrol on growth of 4T1 breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:1001–1005. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiraga T, Ueda A, Tamura D, Hata K, Ikeda F, Williams PJ, Yoneda T. Effects of oral UFT combined with or without zoledronic acid on bone metastasis in the 4T1/luc mouse breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;106:973–979. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michigami T, Hiraga T, Williams PJ, Niewolna M, Nishimura R, Mundy GR, Yoneda T. The effect of the bisphosphonate ibandronate on breast cancer metastasis to visceral organs. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;75:249–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1019905111666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantena SK, Sharma SD, Katiyar SK. Berberine, a natural product, induces G1-phase cell cycle arrest and caspase-3-dependent apoptosis in human prostate carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;5:296–308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jadeski LC, Hum KO, Chakraborty C, Lala PK. Nitric oxide promotes murine mammary tumour growth and metastasis by stimulating tumour cell migration, invasiveness and angiogenesis. Int. J. Cancer. 2000;86:30–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000401)86:1<30::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orucevic A, Bechberger J, Green AM, Shapiro RA, Billiar TR, Lala PK. Nitric-oxide production by murine mammary adenocarcinoma cells promotes tumor-cell invasiveness. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;81:889–896. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990611)81:6<889::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Méry PF, Pavoine C, Belhassen L, Pecker F, Fischmeister R. Nitric oxide regulates cardiac Ca2+ current. Involvement of cGMP-inhibited and cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterases through guanylyl cyclase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:26286–26295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomsen LL, Miles DW, Happerfield L, Bobrow LG, Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthase activity in human breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;72:41–44. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dueñas-Gonzalez A, Isales CM, del Mar Abad-Hernandez M, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R, Sangueza O, Rodriguez-Commes J. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in breast cancer correlates with metastatic disease. Mol. Pathol. 1997;10:645–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]