Abstract

Background

Normal tissue radiation injury is associated with loss of vascular thromboresistance, notably because of deficient levels of endothelial thrombomodulin (TM). TM is located on the luminal surface of most endothelial cells and serves critical anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory functions. Chemical oxidation of a specific methionine residue (Met388) at the thrombin-binding site in TM reduces its main functional activity, i.e., the ability to activate protein C. We examined whether exposure to ionizing radiation affects TM in a similar manner.

Methods

Full length recombinant human TM, a construct of epidermal growth factor-like domains 4–6 that are involved in protein C activation, and a synthetic peptide containing the methionine of interest, were exposed to gamma radiation in a cell-free system, ie, a system not confounded by TM turnover or ectodomain shedding. The influence of radiation on functional activity was assessed with the protein C activation assay; formation of TM-thrombin complex was assessed with surface plasmon resonance (Biacore), and oxidation of Met388 was assessed by HPLC and confirmed by mass spectroscopy.

Results

Exposure to radiation caused a dose dependent reduction in protein C activation, impaired TM-thrombin complex formation, and oxidation of Met388, all in a radiation dose dependent manner.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate that ionizing radiation adversely affects the TM molecule. Our findings may have relevance to normal tissue toxicity in clinical radiation therapy, as well as to the development of radiation syndromes in the non-therapeutic radiation exposure setting.

INTRODUCTION

Thrombomodulin (TM) is a transmembrane glycoprotein with potent anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory functions, located on the luminal surface of most normal endothelial cells. Endothelial TM forms a complex with thrombin and essentially converts thrombin from a procoagulant to an anticoagulant by changing its substrate specificity. Thrombin, when bound to TM, loses its ability to cleave fibrinogen to form fibrin and to activate proteinase-activated receptors and instead acquires the ability to activate protein C, a potent anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory protein (1). Clinical studies and experiments in animal models demonstrate that exposure of normal tissues to ionizing radiation is associated with rapid and sustained loss of endothelial TM (2,3). These and other corroborating data suggest that loss of TM may be a critical factor in radiation-induced endothelial dysfunction and contribute substantially to development of early and delayed radiation toxicities in normal tissues (reviewed in 4,5).

The mechanisms responsible for post-radiation loss of TM expression and/or activity are multifactorial. First, many cytokines that are upregulated during the radiation response, such as interleukin 1 (IL1), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) reduce TM expression at the transcriptional level (6–9). The transcription factor nuclear factorκB (NFκB), which is activated by radiation as well as in response to cytokines that are released in increased amounts during inflammation, may also be involved in the regulation of TM (10). Second, TM may be cleaved from the endothelial cell membrane and released into the circulation (ectodomain shedding) by a variety of proteinases that are present at increased level during inflammation (11,12). While increased circulating TM levels are observed particularly in situations with systemic endothelial involvement, ectodomain shedding may also be important in conditions with localized endothelial dysfunction, such as, after localized radiation exposure (13,14). The third and most specific mechanism by which radiation may affect endothelial TM is by oxidation of a specific methionine (Met388) that is highly susceptible to oxidation and critical for TM’s ability to form a complex with thrombin and subsequently activate protein C (15). The critical role of Met388 has been shown in studies using chemical oxidants (15). We surmised that an initial reduction in TM function by oxidation of Met388 could help explain the particularly profound loss of TM in irradiated tissues.

The objective of this study was to investigate whether ionizing radiation adversely affects TM’s ability to activate protein C and, if so, if this is associated with reduced TM-thrombin complex formation and oxidation of Met388. We demonstrate here that TM functional activity and TM-thrombin complex formation are impaired by exposure to ionizing radiation and that this parallels oxidation of Met388. These findings may have implications for development of normal tissue toxicity after clinical radiation therapy, as well as to the development of radiation syndromes in the context of radiation or nuclear accidents and/or terrorism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experiments were performed in a cell-free system, ie, in a system not confounded by transcriptional regulation or ectodomain shedding of TM. The functional activity of TM was assessed with the protein C activation assay, interaction between TM and thrombin was monitored using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and oxidation of Met388 was assessed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with mass spectroscopy (MS) confirmation.

Irradiation

All samples were dissolved in buffer (see below) and irradiated in 1 ml polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes (Cat # 02-681-374, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in a total volume of 500 μL. The TM samples were stored at 4°C as recommended by the supplier for optimal long term stability. Before irradiation, the samples were placed at room temperature for 1 hour to ensure stable and equal sample temperature. After irradiation, the samples were returned to 4°C within 20 minutes, but no sooner than 15 minutes after irradiation. This protocol minimized intra- and inter-experimental variability and ensured that the exposure to radiation (or sham-irradiation) was the only variable across all experiments.

Irradiation was performed in a Gammacell 1000, model B (with 2 cesium capsules) Cs-137 irradiator (Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd., Kanata, Ontario, Canada) with dose-rate 5.90 Gy/minute. Constant placement of the samples within the 95% isodose area in the irradiator was ensured by placing the samples in a circular configuration on a round plastic rack with a capacity of 8 tubes, elevated by 25 mm, and centered on a turntable rotating at 4 rpm.

Samples were exposed to graded single or fractionated radiation doses, with the lowest radiation dose (1.77 Gy) being close to the fraction size of 1.8–2 Gy commonly used in clinical radiation therapy. At least 3 independent TM samples were irradiated at each dose level for all experiments, not including optimization and validation studies, and separate sets of samples were irradiated for each of the 3 endpoints (protein C activation assay, SPR, HPLC/MS).

TM Activity

The effect of single dose irradiation on TM functional activity was assessed with the protein C activation assay after exposure to 0, 1.77 (0.3 min radiation exposure), 10 (1.7 min), 20 (3.4 min), 40 (6.8 min), and 80 Gy (13.6 min). The dose 1.77 Gy was used for practical reasons because the timer on the irradiator operated in 0.1 minute increments.

The studies were performed using a recombinant human TM molecule (Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, IN) comprised of the extracellular portion of TM (the N-terminal lectin-binding domain, the 6 epidermal growth factor [EGF]-like repeats, and the serine/threonine-rich domain) without the transmembrane and intracellular domains and, importantly, without the chondroitin sulfate moiety. TM was dissolved to a final concentration of 50 nM in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.1% polyethylene glycol, pH 8.0 (15).

The response to fractionated irradiation was investigated by comparing the activity of recombinant TM exposed to 6 or 12 fractions of 1.77 Gy with the activity of TM exposed to the same total radiation doses administered as single exposures (10.62 Gy [6 × 0.3 min] or 21.24 [12 × 0.3 min] Gy, respectively). Fractionated irradiation was performed with twice-daily fractions separated by 6 hours, and the experiment was designed to maintain the time between the last fraction and performance of the protein C assay constant for all samples. All samples were subjected to the same number of radiation/sham-irradiation procedures (i.e., each was irradiated or sham-irradiated 12 times). All samples for each experiment (fractionated as well as single dose irradiated) were transported to the irradiator together as one batch each time and irradiation was commenced after a uniform period of 1 hour. Samples to be sham-irradiated were treated in identical manner, placed in the irradiator’s chamber for the same time as samples that were irradiated, but without activation of the source.

The radiation response of TM in the presence of myeloperoxidase (MPO) was also investigated. MPO is present in neutrophils and monocytes and is involved in the oxidative burst associated with inflammation, for example in the setting of post-radiation inflammation. MPO catalyzes the formation of hypochlorous acid, a potent oxidative agent, from H2O2 and Cl−. TM samples, to which 1.0 μM MPO (Fischer Scientific, Suwanee, GA) had been added immediately before irradiation, were exposed to 0 Gy, 1.77 Gy, 20 Gy, or 80 Gy and subsequently analyzed by protein C assay to address the possibility of an additive or synergistic effect of MPO on radiation-induced Met388 oxidation, similar to what has been reported for chemical oxidation (15). The MPO concentration used in the present study was the same as that used by Glaser et al. (15).

The protein C activation assay was performed as follows. Irradiated and sham-irradiated samples were diluted to a final concentration of 2.5 nmol/L TM and incubated with 200 nM protein C and 1.4 nM thrombin (60 minutes at 37°C, 1.2 ml total volume) in a 96-well plate to generate activated protein C. The amount of activated protein C generated was measured by monitoring hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate, S-337, at 405 nm in a microplate reader (Bio-TEK Instruments, Winooski, VT) at 5-minute intervals for 60 minutes. The results were expressed as mean OD at 60 minutes. All assays were performed in triplicate and the average was considered a single value for statistical purposes.

Thrombin-TM Complex Formation

The interaction between thrombin and thrombomodulin (TM) was monitored by SPR using a BIAcore 3000 instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Recombinant full length human TM was dissolved to a final concentration of 50 nM or 100 nM in HBS buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 0.005% P20 (a surfactant) at pH 7.4. They were irradiated with 0 Gy, 1.77 Gy, 20 Gy, or 80 Gy as described above and subsequently analyzed using SPR.

In SPR, a light source is polarized and directed at a chip of gold film, the beam being reflected into an optical detection unit. The amount of mass bound to the chip surface changes the angle of reflection and, in turn, changes the refractive index close to the surface of the sensor chip. The detection unit detects the change in angle, referred to as the resonance angle. The change in resonance angle, in Biacore terms, is expressed in Resonance Units (RU), with 1000 RU corresponding to approximately 1 ng of bound protein per mm2 chip surface. A sensogram is a continuous display of RU versus time in seconds, i.e., a real-time representation of mass associating and/or dissociating on the surface of the chip (16).

Thrombin was dissolved at 60 ng/μL in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) and immobilized on one channel of a CM-5 sensor chip (research grade, Biacore AB). Thrombin amine groups were covalently bound to activated carboxyl groups on the sensor chip using the Biacore Amine coupling kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions and in accordance with the methods described by Kishida et al. (16). Thrombin immobilization resulted in approximately 4000 resonance units (RU) bound to the chip surface. Another channel was activated and blocked with 1.0 M ethanolamine at pH 8.5 for six minutes at 5 μL/minute for use as a blank, without bound thrombin. Although the availability of free amine groups on lysines is important for thrombin-TM complex formation, the random nature of amine coupling, the many lysines in thrombin, and the high number of thrombin molecules bound to the chip ensured that a sufficient number of thrombin molecules would be available to bind TM.

Fifteen μL of 50 nM TM in HBS buffer was passed over the immobilized thrombin at a rate of 5 μL/minute. Sensograms were collected in real time as the difference between binding of the thrombin-containing channel and non-specific binding of the blank reference channel, i.e., RU values for the blank channel were subtracted from those of the thrombin-containing channel to account for non-specific binding of TM to the matrix. The association phase of the binding reaction consisted of a 3 minute injection of TM at a rate of 5 μL/minute, followed by a wash with HBS buffer for 4 minutes at 5 μL per minute to monitor the dissociation of TM. The chip surface was regenerated by washing with 1.5 M NaCl for 1 minute. The baseline was allowed to stabilize for 5 minutes before injection of the next sample. The change in response from baseline was measured for each sample and compared. After optimization of the SPR procedure, SPR was performed 3 times (on separate days) at each radiation dose level.

Oxidation of Met388

To avoid confounding by methionines elsewhere in the TM molecule, a synthetic 13-amino acid peptide containing Met388 (APIPHEPHRCQMF), and a TM fragment consisting of TM EGF-like domains four, five and six (TMEGF456), the region containing Met388 and responsible for protein C activation, were used to determine oxidation of Met388 by HPLC/MS.

Three separate samples were analyzed per radiation dose level. At each run, each sample was used for 3–4 injections, again with the average being considered a single value.

Peptide preparation

5 mg of the peptide APIPHEPHRCQMF (synthesized by SIGMA Genosys) was dissolved in 500 μL of 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 (1.46 mM KH2PO4, 9.9 mM Na2HPO4, 2.68 mM KCl, 0.137 M NaCl) then brought to a final concentration of 50mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP) (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) by adding 25 μL of a 1 M stock of TCEP buffered with 750 mM potassium phosphate tribasic, to pH 7.0. Further purification was performed with HPLC under reducing conditions, while separating oxidized and un-oxidized peptide. The samples were placed in 1 mL borosilicate glass tubes (VWR International, West Chester, PA) until irradiated.

Purification of TMEGF456

A recombinant form of thrombomodulin epidermal growth factor-like domains four, five, and six (TMEGF456), ranging residues 365 to 481 and an additional N-terminal His-Met sequence, was expressed in P. pastoris as described by Wood et al. (17). The expression system was the gracious gift of Dr. Elizabeth Komives at the University of California, San Diego. Upon completion of growth, cells were separated from the growth media by centrifugation and supernatants were decanted from the cell pellets and combined. After adding 1.8 g/L disodium EDTA (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ), the supernatant was pumped using a FMI Q model rotary piston pump (Fluid Metering, Inc., Syosset, NY) at 5 mL/minute over a 10mL bed volume of Q Sepharose FF (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) packed into a 10×100mm column, previously equilibrated with 4 bed volumes of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1. Three elution buffers were prepared for a step gradient: Eluent A consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1, 0.625 M NaCl, eluent B consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1, 1.25M NaCl, and eluent C consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.1, 2M NaCl. The three buffers were pumped over the column in series, each for 10 minutes at 5 mL/minute, and collected separately. Eluent B, usually containing the TMEGF456, was concentrated to 4 ml in Amicon Centricon Plus-20 Filter Unit with Biomax-5 membrane by centrifugation at 3000 rpm (1868 RCF) in a SH-3000 rotor for 30 minutes at 4 °C. The retentate was purified by reverse phase chromatography using a Grace Vydac C18 4.6×250mm 3 μm column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA) held at 60°C. The column was equilibrated for at least 12 minutes (4 column volumes) at the starting condition of 90% H2O/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 10% acetonitrile (MeCN)/0.1% TFA at a 1 mL/minute flow rate. Four mL samples were injected using a Waters 717+ Auto-sampler. After the last injection, the solvent was changed from 10% to 26% MeCN/0.1% TFA over 9 minutes. The gradient was then slowed, changing from 26 to 40% of MeCN/0.1% TFA over 21 minutes. TMEGF456 elutes in a broad range between 18–21 minutes as monitored by absorbance at 214 nm. Fractions were collected in 1 mL aliquots using a Gilson FC-204 Fraction Collector and the pH of each fraction was adjusted to 7.0 using 100 μL of 200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The samples were then lyophilized in 1100 μL aliquots on a high vacuum line and stored at −80°C. The dry powder was dissolved in a small volume of 1X PBS. Concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm and the molar absorption coefficient of 6720 M−1cm−1 as calculated by the method of Pace et al. (18). Samples were diluted to 10 μg/mL (75 nM) and 500 μL aliquots were frozen until irradiated.

HPLC Separation of Oxidized and Unoxidized Methionine Containing Peptides

Samples were diluted in distilled water to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml before single-dose irradiation (0, 1.77, 10, 20, 40, or 80 Gy). Samples were reduced with an additional 50mM of fresh TCEP, pH 7.0 from a 1 M stock solution and allowed to mix at room temperature for 5 minutes, and then injected to analyze for oxidation. The HPLC method was optimized to observe 20 pmol of peptide using a Waters Atlantis 4.6×250 mm dC18 5 μm reverse phase column heated to 65°C. The gradient, at a constant 1 mL/minute flow rate, starts at 10% MeCN/0.1% TFA and ramps over eight minutes to 20% MeCN/0.1% TFA then, over an additional 20 minutes, changes to 30% MeCN/0.1% TFA.

Digestion and analysis of rTMEGF456 samples

Each 5μg TMEGF456 sample was transferred to 1.5 mL micro-centrifuge tube and lyophilized. Samples were then brought up in 40 μL reduction buffer containing 1X PBS, pH 7.4, 50 mM TCEP pH 7.0, and 200U PNGase F (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Samples were simultaneously reduced and deglycosolated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Chymotrypsin (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ) was prepared to manufacturer’s specifications at 1 μg/μL in 25 μL of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM CaCl2, 2.5 μg chymotrypsin was added to each tube, and the samples were placed in a shaker for 4 hours at 30°C. After incubation, the samples were boiled for 45 seconds to deactivate chymotrypsin and stored at −80°C until analysis by HPLC. Each digest was subjected in triplicate to the HPLC analysis described above.

Mass spectroscopy confirmation

Peak locations and identities in the more complex peptide digest mixture were confirmed using HPLC co-injections of synthetic peptide and by mass spectroscopy. Fractions were taken of peaks thought to correspond to the oxidized and reduced forms. These solutions were mixed with dihydroxybenzoic acid, spotted onto target plates, and allowed to dry before insertion into a Bruker MALDI-TOF Reflex III mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) for confirmation.

Statistical Analysis

For each of the parameters (protein C activation, SPR RUs, and Met388 oxidation), the Jonckheere-Terprstra test was used to determine whether there was a radiation dose-dependent increase/decrease, using the CytelStudio/StatXact 8 software package for exact non-parametic inference (Cytel Software, Cambridge, MA). The Jonckheere-Terprstra test is similar to the Kruskall-Wallis test (non-parametric one-way analysis of variance), but makes the additional assumption that the populations are not random, but rather exhibit a trend (in this case a radiation dose-dependent trend). Selected univariate comparisons of individual differences were performed with Student’s t-test. An alpha level of 0.05 was established as level of significance for all tests.

RESULTS

TM Activity

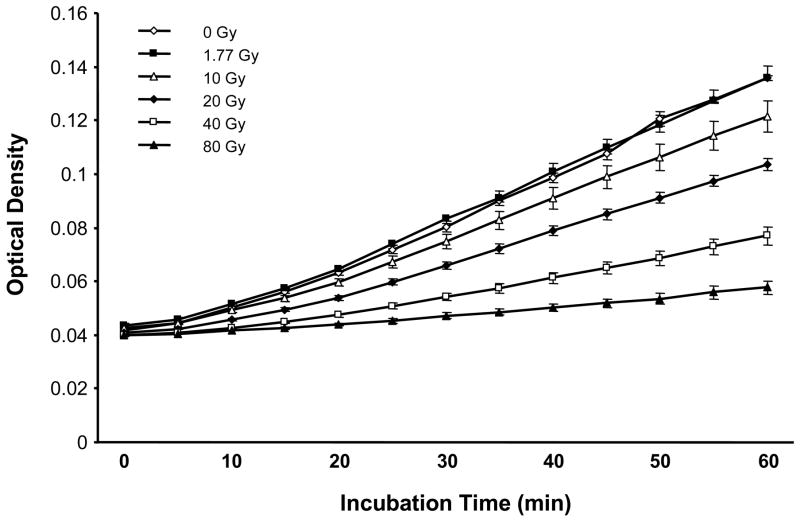

Radiation exposure of recombinant human TM caused a strong, highly statistically significant dose-dependent decrease in TM functional activity as assessed by the protein C activation assay (p=6 × 10−8, Figure 1). There was no decrease in TM activity at 1.77 Gy, whereas, at 10 Gy, the decrease was already significant (p=0.03).

Figure 1. Functional activity of TM exposed to single dose irradiation.

There is a highly statistically significant radiation dose-dependent inhibition of TM’s cofactor function as measured by the protein C activation assay (p=6×10−8). Data points represent mean and standard error of 3 independent samples.

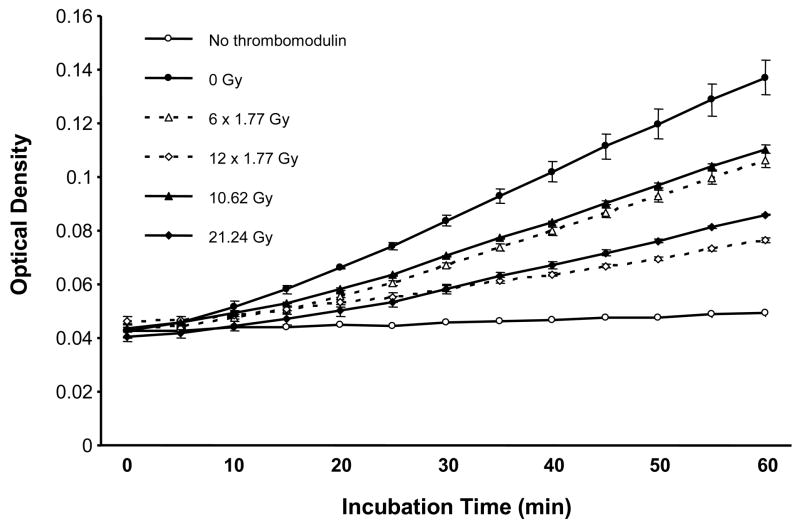

Exposure to fractionated radiation revealed a highly statistically significant reduction in TM’s ability to activate protein C, both after 6 fractions (p=0.001) and after 12 fractions (p=0.0001) of 1.77 Gy (Figure 2). There was no difference in TM activity whether a dose of 10.62 Gy was delivered as a single fraction or as 6 fractions (p=0.11). Interestingly, 21.24 Gy delivered as 12 fractions was associated with significantly greater reduction in protein C activation than when the radiation dose was administered as a single exposure (p=0.003).

Figure 2. Functional activity of TM exposed to fractionated irradiation.

TM’s ability to activate protein C is highly significantly reduced, both after 6 fractions of 1.77 Gy (p=0.001), as well as after 12 fractions of 1.77 Gy (p=0.0001). There is no difference in TM activity whether the dose of 10.62 Gy was delivered as a single fraction or as 6 fractions (p=0.11), whereas, 21.24 Gy delivered as 12 fractions was associated with significantly greater reduction in protein C activation than when administered as a single dose (p=0.003). Data points represent mean and standard error of 3 independent samples.

MPO enhanced the radiation dose-dependent reduction in protein C activation at every dose level examined (p<0.05 at every dose level, Table 1). For example, while exposure to 1.77 Gy without MPO caused a mean reduction in protein C activation of 12% in this experiment, the same radiation dose reduced protein C activation by 40% in the presence of MPO.

Thrombin-TM Complex Formation

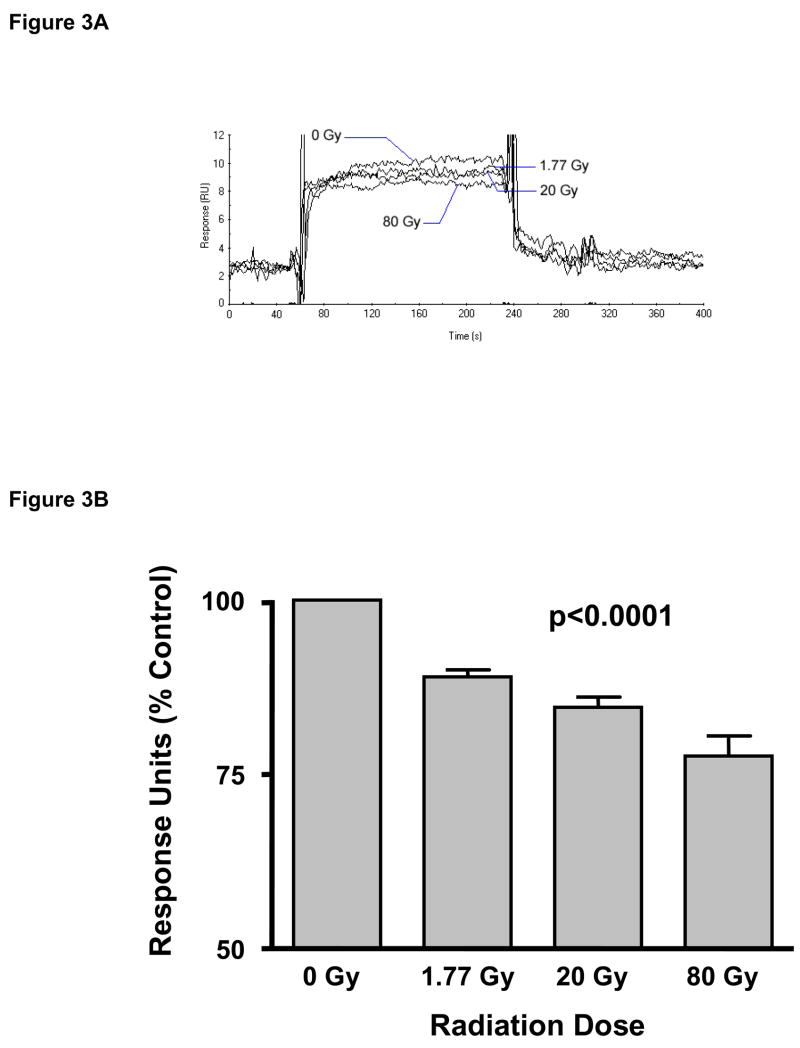

Sensograms (an example is shown in Figure 3A) were recorded for each experiment. The bar graph depicted in Figure 3B shows the average RU values after radiation exposure (relative to the 0 Gy sample) from 3 independent experiments. Exposure to ionizing radiation caused a highly statistically significant dose-dependent decrease in the interaction between thrombin and thrombomodulin (p=0.00006). Relative to baseline (0 Gy), the average RU value decreased by 13.2±1.0% after exposure to 1.77 Gy, by 18.9±1.7% after 20 Gy, and by 21.6±1.8% after 80 Gy.

Figure 3. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) analysis.

Panel A: Overlay of 4 different sensograms to demonstrate how the SPR response of TM exposed to different doses of radiation can be compared. Panel B: Average TM-thrombin complex formation as a function of radiation dose (mean and standard error for response units [RU] obtained from sensograms, as percent of sham-irradiated control). There is a highly statistically significant radiation dose-dependent decrease in the association between TM and thrombin (p=0.00006). Average and standard error of 3 separate experiments.

Oxidation of Met388

Following chymotrypsin digestion of TMEGF456, the resultant peptide was structurally identical to the synthetic peptide. The oxidized peak in both the synthetic peptide and the digested TMEGF456 eluted at 14.7 minutes and the unoxidized peak eluted at approximately 18.3–18.4 minutes. These peaks were baseline separated from the other peaks of the digest.

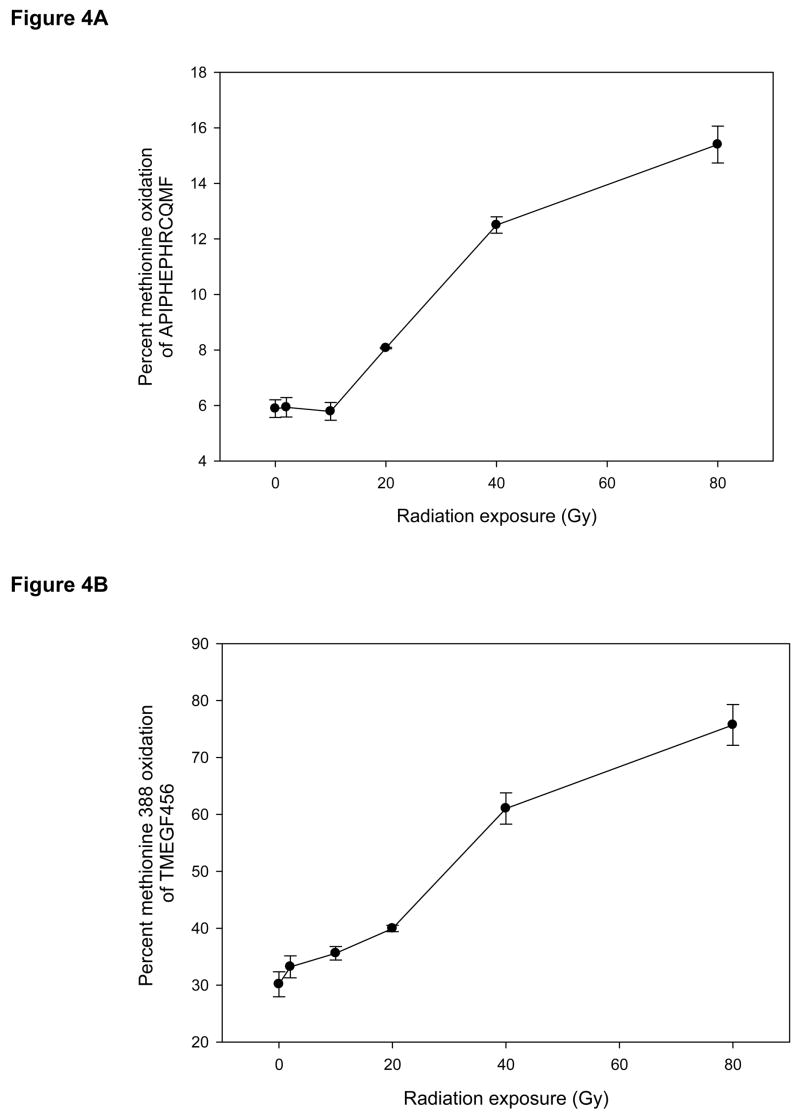

There was a highly statistically significant radiation dose-dependent increase in Met388 oxidation of the synthetic peptide (p=0.0001, Figure 4A), although there was little change in oxidation at lower levels of radiation exposure.

Figure 4. Oxidation of methionine 388 (Met388) as a function of radiation dose.

Panel A: Met388 oxidation in synthetic peptide as a function of radiation dose. Panel B: Met388 oxidation in the recombinant TME456 fragment as a function of radiation dose. Data points are mean and standard deviation from at least 3 separate samples. There are highly statistically significant radiation dose-dependent increases in Met388 oxidation both of the synthetic peptide and of TME456 (p=0.0001 and p=4×10−9, respectively).

Samples of the recombinant protein fragment TMEGF456 started out with about 30% of Met388 already in the sulfoxide form. In contrast to the synthetic peptide, TMEGF456 showed increased oxidation even after the lower radiation doses, and exhibited a highly statistically significant increase in Met388 oxidation with increasing radiation exposure (p=4 × 10−9, Figure 4B).

Mass spectroscopy confirmed that the molecular ions were of the expected mass in each case.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that ionizing radiation impairs the ability of TM to activate protein C, reduces formation of the TM-thrombin complex, and that it causes oxidation of the critical amino acid residue Met388. It also shows that functional impairment of TM is greatly enhanced by exposure to radiation in the presence of MPO and that, in a cell-free system without TM turnover, there is no sparing from fractionated irradiation.

These findings have relevance to the change in TM seen in normal tissues after irradiation. In the post-radiation situation, TM expression is downregulated by inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL1, or IL6, NFkB (6,8–10), or by exposure to lipopolysaccharide or endotoxin (19). TM may also be shed into the blood stream by being cleaved from the endothelial plasma membrane by ectodomain shedding (12,20). While these processes do occur in inflamed normal tissues after irradiation, they do not alone explain the profoundly deficient TM activity/expression seen after irradiation compared to other insults or in other inflammatory conditions. The findings from the present study are consistent with the notion that radiation-induced oxidative inactivation of TM might contribute to initiating the process that leads to deficient endothelial thromboresistance after exposure of normal tissues to ionizing radiation.

Glaser et al. showed that oxidation of TM by H2O2 in the presence of hypochlorous acid generated from H2O2 by MPO, can decrease TM cofactor activity up to 75–90% (15). Using leucine substitution in place of the two methionine residues in the EGF-like domains (Met291 and Met388), they also showed that substitution of Met388 (in contrast to substitution of Met291) produced TM analogues that were resistant to oxidative inactivation, thus demonstrating the critical role of Met388 for TM co-factor function and protein C activation (15). TMEGF456 is the smallest fragment of TM that retains functional activity and Met388 is one of three linker residues between the fourth and fifth EGF-like domains (21,22). NMR studies have shown that Met388 oxidation causes conformational changes in TMEGF5, in which several of the thrombin-binding residues are packed into the hydrophobic core, resulting in impaired interaction with thrombin and a 5-fold decrease in the kcat for protein C activation (23). Therefore, Met388 oxidation very likely accounts for the decrease in thrombin binding observed by SPR in the present study.

Because this study used 3 different analytical techniques to assess the effect of radiation on different aspects of TM (protein C activation assay to measure functional activity, SPR to measure TM-thrombin complex formation, and HPLC/MS to assess Met388 oxidation), the data from the present study do not lend themselves to direct comparison across methods, but rather demonstrates a radiation dose-dependent change. Hence, a given change in methionine oxidation does not necessarily translate into a change in cofactor function of similar magnitude. In all experiments, however, using tightly controlled conditions with radiation dose as the only variable, there was a highly statistically significant radiation dose-dependent change with p-values <0.0001 or smaller for all analyses.

Our finding of significantly reduced TM cofactor activity after clinically relevant fractionated radiation doses has significant translational implications. First, methionine sulfoxide reductases A and B, the known enzymes that could potentially reduce oxidized Met388, are located intracellularly (24). Because the major part of TM (including Met388) is located extracellularly, it is thus unlikely that the effect of radiation on TM during a course of fractionated radiation in vivo will be “repaired” between individual fractions. Rather, the effect will most likely be cumulative as shown in the acellular system used in the present study. Second, during a course of fractionated irradiation, normal tissues will generally exhibit progressive inflammation with increasing infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages from the beginning to the end of the radiation course (25,26). Similar to the findings in the present study, studies with chemical oxidation of TM have shown a significant effect of MPO (15). During radiation-induced inflammation, it is likely that infiltration of MPO-producing cells would further exacerbate the impairment of TM function. Because the concentration of MPO used in the present study is higher than one would normally encounter the blood stream in vivo, it is difficult to estimate the magnitude of this latter effect in vivo. Moreover, it appears that the effect of MPO with exposure to ionizing radiation, in contrast to chemical oxidation (15), is additive rather than synergistic. However, even without the addition of MPO, there was substantial inhibition of TM function after exposure to 10.6 or 21.2 Gy given as 6 or 12 fractions of 1.77 Gy, i.e., a fraction size that is clearly in the clinically relevant range. The differences in dose between 10 and 10.62 Gy and between 20 and 21.24 Gy are not sufficient to explain the difference in protein C activation between the single dose and fractionated experiments. Also, all samples received identical treatments with the radiation dose being the only variable. It is conceivable that the difference may have to do with repeated cycling between 4°C and room temperature (12 times for the fractionated experiments, once for the single dose experiment). On the other hand, because of the fast kinetics of the oxidation process (27,28) and absence of agents the could reduce the sulfoxide after radiation exposure, this is considered a remote possibility.

While the results from the present study are consistent with the notion that oxidation may contribute to the reduction in vascular thromboresistance seen after clinically relevant courses of fractionated radiation, it is not appropriate to “model” the exact impact of Met388 oxidation and extrapolate to the in vivo situation. On one hand, the half-life of TM on the endothelial cell membrane is indeed sufficiently long to suggest that cumulative oxidation may be important (8,29). On the other hand, other factors, such as, alterations in TM transcription, TM mRNA stability, and ectodomain shedding, all of which might change during a course of fractionated radiation therapy, represent major confounders. Therefore, while our data certainly suggests that TM oxidation by ionizing radiation may contribute to post-radiation loss of vascular thromboresistance, the complexity of the in vivo situation precludes estimation or measurement of its precise impact.

It is important to recognize that the main physiological function of TM is to regulate the function of thrombin, a central enzyme in the cascade of proteinase clotting factors generally referred to as the “coagulation cascade”. Deficiencies in certain “proximal” coagulation factors, e.g., factor VIII and factor IX, does not cause severe clinically symptoms unless the levels are reduced by 70% or more. On the other hand, there is significant human data suggesting that a dysfunction of the TM-thrombin-protein C system is considerably more sensitive to perturbation. For example, studies of mutations in the TM-thrombin-protein C system show that heterozygous carriers of mutations in TM (30), heterozygous carriers of mutations in protein C (31), and individuals heterozygous for factor V Leiden (32), where activated factor V is resistant to inhibition by activated protein C, all exhibit increased thrombophilia. Therefore, a decrease in TM cofactor function of the magnitude reported here may well be biologically significant, particularly in a situation with fractionated radiation where accumulation of damage may occur. Moreover, as recently pointed out by Camerer (33), although some loss of function of TM-protein C system may be relatively well tolerated under normal conditions, reduced protein C activation capacity becomes critical under conditions that require increased protein C activation to counteract loss of endothelial thromboresistance, as occurs, for example, after exposure of normal tissues to ionizing radiation.

There is no established consensus as to how the binding of TM to thrombin should be studied by SPR when thrombin is bound to the chip. In the present study, we used the amine coupling reaction described by Kishida et al. (16). While the importance of the free amine groups of lysines in the binding interaction between thrombin and TM is recognized, the conditions used here would result in anchoring of only a few random amine groups per thrombin, thus leaving other lysines free to participate in complex formation with TM. Given the number and location of lysines in thrombin and the number of thrombin molecules bound to the chip, only a small percentage of molecules will likely be bound in an orientation that would hinder TM binding. While it is possible that another method of anchoring thrombin to the chip could have further enhanced thrombin-TM complex formation, it is difficult to imagine an alternative explanation (i.e., other than a radiation effect) for the highly statistically significant radiation dose-dependent reduction in complex formation under otherwise identical conditions.

The sensograms obtained in the present study are consistent with the rapid rates of association and dissociation between thrombin and TM described by Kishida et al. (16) with thrombin bound to the SPR chip, as well as with reports by Baerga-Ortiz et al. (34) with TM bound to the chip surface thrombin in the mobile phase. The latter group reported specific, extremely fast, rates of association (6.7×106 m−1s−1) and dissociation (0.033 s−1).

In addition to the TMEGF456 region, the chondroitin sulfate (CS) moiety of TM is also able to form a complex with thrombin, although with much lower affinity (35). This binding supports thrombin-induced inactivation of single-chain urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and accelerates the inactivation of thrombin by antithrombin III and protein C inhibitor. The recombinant TM used in the present study lacked the CS moiety and thus competing binding and/or inactivation of TM was not a confounding factor.

Met388 is one of 3 linker residues between EGF-like domains 4 and 5 in TM, the region that has been shown to be critical for TM function (21). Studies using chemical oxidation have shown that, in contrast to oxidation of other methionines in TM, oxidation of Met388 is sufficient and required for inhibition of TM cofactor activity (15,23). Hence, in the present study, HPLC/MS analysis was performed with a synthetic 13-amino acid peptide containing “Met388” and a TM fragment that comprised EGF-like domains 4–6 (and thus included Met388). While it is likely that exposure of TM to ionizing radiation also causes oxidation of other residues, oxidation at sites other than Met388 is extremely unlikely to cause any major change in TM function, based on chemical oxidation studies. The lower radiation doses (1.77 Gy and 10 Gy) did not cause appreciable methionine oxidation in the peptide, but did cause oxidation of TMEGF456. This may be attributable to differences in cysteines. Hence, while the peptide is identical in sequence to the corresponding region of the intact protein and to TMEGF456, there is one key difference. The peptide is purified in the reduced form and the free thiol of the cysteine can be oxidized to the disulfide. The cysteines in the protein, on the other hand, are disulfide bonded and thus are not potential sinks for oxidants.

Methionine oxidation in proteins and its biological consequences has become an area of intense interest and investigation in a variety of disciplines, including cell signaling, cardiovascular diseases, and aging (reviewed in 36). Again, because methionine sulfoxide reductase is localized intracellularly, intracellular methionine oxidation may be reversible, while extracellular methionine oxidation is generally considered irreversible.

An example of methionine oxidation that relates to normal tissue radiation toxicity is the activation of transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1), a factor that plays a major role in radiation fibrogenesis in many normal tissues. The activity of TGFβ1, is modulated by oxidation (37), and it has been shown that oxidation of a methionine in position 253 in the latency-associated peptide leads to isoform-specific activation of TGFβ1 (38), the predominant fibrogenic isoform.

Another example of methionine oxidation with biological consequences and possible relevance to radiation therapy, but where the direct relationship to radiation remains to be shown, relates to α1-antitrypsin. Oxidation of either methionine 351 or 358 in the binding site of α1-antitrypsin destroys the its ability to bind to and inhibit elastase (39). This mechanism appear to play a significant role in linking tobacco smoking to lung emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (40). Analogously, smoking also increases Met388 oxidation in TM (41). It is interesting to speculate that the reason why smoking is an important independent predictor of side effects after radiation therapy (42) may be related to oxidative changes in the function of α1-antitrypsin, TGF- β1, and/or TM.

In conclusion, ionizing radiation may decrease endothelial TM in normal tissues not only by ectodomain shedding and downregulation at the transcriptional level during inflammation, but may initially also impair TM activity by a mechanism that involves reduced TM cofactor function because of radiation-induced oxidation of Met388. These findings have relevance to early and delayed radiation responses in normal tissues after radiotherapy for cancer, as well as to development of radiation syndromes after non-therapeutic radiation exposure scenarios.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (CA83719), Veterans Administration (Deployment-Related Health Initiative) and DTRA (HDTRA1-07-C-0028) to Dr. Martin Hauer-Jensen and by the Arkansas Biosciences Institute and NIH (HL078994) to Dr. Wesley E. Stites.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: epidermal growth factor, EGF; high performance liquid chromatography, HPLC; mass spectroscopy, MS; myeloperoxidase, MPO; nuclear magnetic resonance, NMR; surface plasmon resonance, SPR; thrombomodulin, TM; the fragment of TM containing the fourth, fifth, and sixth EGF-like domains, TMEGF456; transforming growth factor β, TGFβ; tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine, TCEP.

References

- 1.Esmon CT. New machanisms for vascular control of inflammation mediated by natural anticoagulant proteins. J Exp Med. 2002;196:561–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter KK, Fink LM, Hughes BM, Sung CC, Hauer-Jensen M. Is the loss of endothelial thrombomodulin involved in the mechanism of chronicity in late radiation enteropathy? Radiother Oncol. 1997;44:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Zheng H, Ou X, Fink LM, Hauer-Jensen M. Deficiency of microvascular thrombomodulin and upregulation of protease-activated receptor 1 in irradiated rat intestine: possible link between endothelial dysfunction and chronic radiation fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2063–2072. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61156-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauer-Jensen M, Fink LM, Wang J. Radiation injury and the protein C pathway. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:S325–S330. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000126358.15697.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Boerma M, Fu Q, Hauer-Jensen M. Significance of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of early and delayed radiation enteropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3047–3055. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nawroth PP, Handley DA, Esmon CT, Stern DM. Interleukin 1 induces endothelial cell procoagulant while suppressing cell-surface anticoagulant activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3460–3464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway EM, Rosenberg RD. Tumor necrosis factor suppresses transcription of the thrombomodulin gene in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5588–5592. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lentz SR, Tsiang M, Sadler JE. Regulation of thrombomodulin by tumor necrosis factor-α: comparison of transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. Blood. 1991;77:542–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohji T, Urano H, Shirahata A, Yamagishi M, Higashi K, Gotoh S, Karasaki Y. Transforming growth factor beta1 and beta2 induce down-modulation of thrombomodulin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:812–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sohn RH, Deming CB, Johns DC, Champion HC, Bian C, Gardner K, Rade JJ. Regulation of endothelial thrombomodulin expression by inflammatory cytokines is mediated by activation of nuclear factor-kappa B. Blood. 2005;105:3910–3917. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii H, Uchiyama H, Kazama M. Soluble thrombomodulin antigen in conditioned medium is increased by damage of endothelial cells. Thromb Haemost. 1991;65:618–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehme MWJ, Deng Y, Raeth U, Bierhaus A, Ziegler R, Stremmel W, Nawroth PP. Release of thrombomodulin from endothelial cells by concerted action of TNF-α and neutrophils: in vivo and in vitro studies. Immunology. 1996;87:134–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Q, Zhao Y, Xu C, Yu Z, Yao D, Gao Y, Ruan C. Increase in plasma thrombomodulin and decrease in plasma von Willebrand factor after regular radiotherapy of patients with cancer. Thromb Res. 1992;68:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauer-Jensen M, Kong F-M, Fink LM, Anscher MS. Circulating thrombomodulin during radiation therapy of lung cancer. Radiat Oncol Invest. 1999;7:238–242. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6823(1999)7:4<238::AID-ROI5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser CB, Morser J, Clarke JH, Blasko E, McLean K, Kuhn I, Chang RJ, Lin JH, Vilander L, et al. Oxidation of a specific methionine in thrombomodulin by activated neutrophil products blocks cofactor activity. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:2565–2573. doi: 10.1172/JCI116151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kishida A, Nakashima M, Sakamoto N, Serizawa T, Maruyama I, Akashi M. Study on the complex formation between recombinant human thrombomodulin fragment and thrombin using surface plasmon resonance. Am J Hematol. 2000;63:136–140. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(200003)63:3<136::aid-ajh5>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood MJ, Komives EA. Production of large quantities of isotopically labeled protein in Pichia pastoris by fermentation. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:149–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1008398313350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore KL, Andreoli SP, Esmon NL, Esmon CT, Bang NU. Endotoxin enhances tissue factor and suppresses thrombomodulin expression of human vascular endothelium in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:124–130. doi: 10.1172/JCI112772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacGregor IR, Perrie AM, Donnelly SC, Haslett C. Modulation of human endothelial thrombomodulin by neutrophils and their release products. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:47–52. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clarke JH, Light DR, Blasko E, Parkinson JF, Nagashima M, McLean K, Vilander L, Andrews WH, Morser J, Glaser CB. The short loop between epidermal growth factor-like domains 4 and 5 is critical for human thrombomodulin function. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6309–6315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Light DR, Glaser CB, Betts M, Blasko E, Campbell E, Clarke JH, McCaman M, McLean K, Nagashima M, et al. The interaction of thrombomodulin with Ca2+ Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:522–533. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood MJ, Becvar A, Prieto JH, Melacini G, Komives EA. NMR structures reveal how oxidation inactivates thrombomodulin. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11932–11942. doi: 10.1021/bi034646q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vougier S, Mary J, Friguet B. Subcellular localization of methionine sulphoxide reductase A (MsrA): evidence for mitochondrial and cytosolic isoforms in rat liver cells. Biochem J. 2003;373:531–537. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Zheng H, Sung CC, Hauer-Jensen M. The synthetic somatostatin analogue, octreotide, ameliorates acute and delayed intestinal radiation injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:1289–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hovdenak N, Fajardo LF, Hauer-Jensen M. Acute radiation proctitis: a sequential clinicopathologic study during pelvic radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:1111–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albu M, Barnes I, Mocanu R. Kinetic study of the temperature dependence of the OH initiated oxidation of dimethyl sulphide. In: Barnes I, Rudzinsky KJ, editors. Environmental Simulation Chambers: Application to Atmospheric Chemical Processes. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2006. pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams MB, Campuzano-Jost P, Pounds AJ, Hynes AJ. Experimental and theoretical studies of the reaction of the OH radical with alkyl sulfides: 2. Kinetics and mechanism of the OH initiated oxidation of methylethyl and diethyl sulfides; observations of a two channel oxidation mechanism. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:4370–4382. doi: 10.1039/b703957n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dittman WA, Kumada T, Sadler JE, Majerus PW. The structure and function of mouse thrombomodulin. Phorbol myristate acetate stimulates degradation and synthesis of thrombomodulin without affecting mRNA levels in hemangioma cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15815–15822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohlin AK, Marlar RA. The first mutation identified in the thrombomodulin gene in a 45-year-old man presenting with thromboembolic disease. Blood. 1995;85:330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakabayashi T, Mizukami K, Naitoh S, Takeda M, Shikamoto Y, Nakagawa T, Kaneko H, Tarumi T, Mizoguchi I, et al. Protein C Sapporo (protein C Glu 25 --> Lys): a heterozygous missense mutation in the Gla domain provides new insight into the interaction between protein C and endothelial protein C receptor. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:942–950. doi: 10.1160/TH05-05-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchiori A, Mosena L, Prins MH, Prandoni P. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism among heterozygous carriers of factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A mutation. A systematic review of prospective studies. Haematologica. 2007;92:1107–1114. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camerer E. Unchecked thrombin is bad news for troubled arteries. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1486–1489. doi: 10.1172/JCI32473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baerga-Ortiz A, Rezaie AR, Komives EA. Electrostatic dependence of the thrombin-thrombomodulin interaction. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2000;296:651–658. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye J, Esmon CT, Johnson AE. The chondroitin sulfate moiety of thrombomodulin binds a second molecule of thrombin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2373–2379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stadtman ER, Moskovitz J, Levine RL. Oxidation of methionine residues of proteins: biological consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:577–582. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-β. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1077–1083. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.9.8885242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jobling MF, Mott JD, Finnegan MT, Jurukovski V, Erickson AC, Walian PJ, Taylor SE, Ledbetter S, Lawrence CM, et al. Isoform-specific activation of latent transforming growth factor beta (LTGF-beta) by reactive oxygen species. Radiat Res. 2006;166:839–848. doi: 10.1667/RR0695.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taggart C, Cervantes-Laurean D, Kim G, McElvaney NG, Wehr N, Moss J, Levine RL. Oxidation of either methionine 351 or methionine 358 in alpha-1-antitrypsin causes loss of anti-neutrophil elastase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27258–27265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carp H, Miller F, Hoidal JR, Janoff A. Potential mechanism of emphysema: alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor recovered from lungs of cigarette smokers contains oxidized methionine and has decreased elastase inhibitory capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2041–2045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Froude JW, Hauer-Jensen M, Stites WE. Thrombomodulin is significantly more oxidized in smokers (Abstr.) Conference of the International Society for the Prevention of Tobacco Induced Diseases (ISPTID) 2007;6:28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eifel PJ, Jhingran A, Badurka DC, Levenback C, Thames HD. Correlation of smoking history and other patient characteristics with major complications of pelvic radiation therapy for cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3651–3657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]