Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor-binding protein 1 (FGF-BP1 is BP1) is involved in the regulation of embryonic development, tumor growth, and angiogenesis by mobilizing endogenous FGFs from their extracellular matrix storage. Here we describe a new member of the FGF-BP family, human BP3. We show that the hBP3 protein is secreted from cells, binds to FGF2 in vitro and in intact cells, and inhibits FGF2 binding to heparin. To determine the function of hBP3 in vivo, hBP3 was transiently expressed in chicken embryos and resulted in >50% lethality within 24 h because of vascular leakage. The onset of vascular permeability was monitored by recording the extravasation kinetics of FITC-labeled 40-kDa dextran microperfused into the vitelline vein of 3-day-old embryos. Vascular permeability increased as early as 8 h after expression of hBP3. The increased vascular permeability caused by hBP3 was prevented by treatment of embryos with PD173074, a selective FGFR kinase inhibitor. Interestingly, a C-terminal 66-amino acid fragment (C66) of hBP3, which contains the predicted FGF binding domain, still inhibited binding of FGF2 to heparin similar to full-length hBP3. However, expression of the C66 fragment did not increase vascular permeability on its own, but required the administration of exogenous FGF2 protein. We conclude that the FGF binding domain and the heparin binding domain are necessary for the hBP3 interaction with endogenous FGF and the activation of FGFR signaling in vivo.

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs)2 represent a large family of polypeptide growth factors. Over 22 FGFs have been described, and they play significant roles during embryonic development and adult tissue repair as well as in cancer, cardiovascular, and other diseases (reviewed in Refs. 1–6). Most recently, an analysis of somatic mutations in a large series of human cancer samples found that the FGF pathway had the highest enrichment for mutated kinases and concluded that this pathway is one of the “driver” pathways of cancer progression (7), further supporting the significance of FGFs.

FGF1 and FGF2 (aka acidic and basic FGF) are the best-studied members of this family. Both are tightly bound to extracellular matrix (ECM) heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). For example, FGF2 is a quite abundant protein in numerous adult tissues, from which it can be extracted as a biologically active growth factor (8). Two distinct endogenous mechanisms have been described by which locally stored FGFs can be delivered from their HSPG storage to their receptors: one mechanism involves digestion of the sugar backbone of HSPGs by heparinases or other glycosaminoglycan-degrading enzymes (9, 10). Another mechanism involves the binding of the extracellularly immobilized FGFs to secreted FGF-binding proteins (FGF-BP or BP) that serve as chaperones for FGFs. Wu et al. (11) isolated the first human FGF-binding protein (HBp17 is BP1) from the supernatants of A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells and found that this BP1 can bind to FGF1 and FGF2 in a reversible manner, protect FGFs from degradation and present FGF1 and 2 to high affinity cell surface receptors in an active form.

Work from different laboratories has shown that BP1 interacts with FGF1, -2, -7, -10, and –22 (12–14). Heparan sulfate and other heparinoids compete with BP1 binding to FGF2 (12, 15), and more recently it was shown that BP1 directly interacts with perlecan, a HSPG present in the basement membrane (13, 16). FGF/FGFR binding requires HSPGs to trigger receptor oligomerization as well as signaling, and the interaction sites have been described at the level of individual amino acids (17–23), although the variable and complex composition of HSPGs have made this a challenging task (reviewed in Refs. 24, 25). Interestingly, BP1 can supplement some of the functions of HSPGs in that it can restore FGF signaling in cells that have been depleted of their HSPGs (26).

At a functional level, addition of recombinant human BP1 protein induced angiogenesis in a chorioallantoic membrane assay (12) and expression of BP1 in SW-13 cells induced the growth of highly vascularized tumors in athymic nude mice (27). Also, expression of human BP1 in chicken embryos resulted in dose-dependent vascular leakage, hemorrhage, and embryonic lethality (28), which matches with increased vascular permeability found as an initial response to a multitude of angiogenic stimuli (29). In support of the role of BP1 as an angiogenic modulator, depletion of endogenous BP1 from human squamous cell carcinoma and colon carcinoma cell lines inhibited the growth and angiogenesis of xenograft tumors in mice (30, 31). Commensurate with a potential role in tumor growth and angiogenesis, BP1 was found up-regulated dramatically during early stages of malignant transformation of skin, colorectal, and pancreatic epithelia and up-regulation was maintained through development into invasive carcinoma of the skin, colon, and pancreas (32–35). These findings support the notion of BP1 as an “angiogenic switch” molecule that controls endogenous FGF activity (30, 31).

Several mammalian homologues with similar functions as the human BP1 were described (32, 36, 37) as well as another member of the human BP gene family, termed BP2 (NP_114156) that is located in close proximity to BP1 on chromosome 4p15.3.3

In the present study, we describe a third human FGF-binding protein, hBP3, with structural homology to BP1 and a distinct genomic location on chromosome 10. We show that the human BP3 is secreted from cells, binds to FGF2, and inhibits heparin binding of FGF2. To evaluate the in vivo activity of hBP3, we monitored vascular permeability by recording the extravascular appearance of FITC-labeled dextran microperfused into chicken embryo vessels. We found a significant increase in vascular permeability within 8 h of expressing hBP3 in chicken embryos. This vascular leakiness is prevented by pretreatment of embryos with a specific inhibitor of FGFR, PD173074 (38–40), supporting a crucial role of endogenous FGFs in the activity of hBP3. Interestingly, expression of a C-terminal fragment of hBP3, which only contains the predicted FGF binding domain (41) but lacks the heparin binding domain, was still able to inhibit FGF2 binding to heparin. In contrast to full-length hBP3, this fragment was only able to increase vascular permeability in vivo with exogenous FGF2 protein. This suggests to us that both domains in hBP3 contribute to its mechanism of action and the in vivo function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Transient Transfections—HEK293T from ATCC were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum. The transfections were carried out using FuGENE6 Transfection Reagent (Roche Applied Science). Briefly, ∼5 × 105 cells/well were seeded in a 6-well plate and incubated overnight in growth medium. The next day, cells were transfected with FuGENE6-DNA complexes (3:1) for 24–48 h.

Ex Ovo Cultivation of Chicken Embryos—Three-day-old fertilized chicken (Gallus gallus) eggs (CBT Farms, Chestertown, MD) were opened, and intact embryos with yolk were placed in 10-cm polystyrene culture dishes (Corning, New York). Embryos were maintained in a humidified water-jacketed incubator at 37 °C.

Plasmid Constructs—The human BP3 encoding cDNA was isolated from human neuroblastoma (ATCC). PCR products (forward primer: 5′-ATGACTCCTCCGAAGCTGCG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GCCGTTCCAGAAATTGACAA-3′) were cloned into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and the in-frame insertion of hBP3 encoding cDNAs was verified by DNA sequencing. To generate the C-terminal 66-amino acid fragment of hBP3, the respective coding sequence was amplified by PCR from the full-length hBP3. (forward primer: 5′-AGTAAGCTTGCACCGCCCAAAGAAAACCCC-3′, reverse primer 5′-GCCGCCTCTAGATCAGCCGTTCCAGAAATTG-3′), and then subcloned into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pFLAG-CMV™-3 vector (Sigma).

Detection of Proteins by Immunoblot—Immunoblot analyses were performed as previously described (12) using mouse anti-V5 (Invitrogen), mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma), mouse anti-FGF2 (Upstate), and mouse anti-actin (Chemicon) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitations—Conditioned media were passed through a 0.22-μm filter and centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 5 min in the presence of protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). Cells were washed 2× in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin). Samples were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Total cell lysate or media immunoprecipitations were run overnight at 4 °C with the indicated antibodies or antibody-conjugated beads.

Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC)—1-ml HiTrap heparin affinity columns (GE Healthcare) were equilibrated with 10 ml of binding buffer (10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) and then loaded with cell supernatants from transfected HEK293T. Columns were then washed with 10 ml of binding buffer and eluted with 20 ml of a gradient of 0–2 m NaCl elution buffer in 10 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) on an FPLC system (Pharmacia LKB). 1-ml fractions were collected for further analysis.

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry—Proteins present in FPLC fractions containing hBP3 by immunoblot were resolved on a 4–12% NUPAGE gel (Invitrogen), visualized by a brief Coomassie Blue stain, and the protein bands migrating with the immunoreactive hBP3 were manually excised from the gel. The gel slices were washed with 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate and incubated with 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate and 10 μl of 10 mm dithiothreitol at 60 °C for 30 min. The tubes were cooled to room temperature, and 10 μl of 55 mm iodoacetamide were added and incubated further for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The solvent was discarded, and the gel slices were washed in 50% acetonitrile/100 mm ammonium bicarbonate, destained with 50% acetonitrile in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate, dehydrated with acetonitrile for 5 min, and vacuum-dried. Gel pieces were then rehydrated with 15 μl of ammonium bicarbonate/acetonitrile (25 mm:10%) supplemented with trypsin (5 ng/μl; Promega) at 37 °C for 16 h. Afterward, tryptic peptides were extracted in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/50% acetonitrile and mixed with equal volume of 5 mg/ml CHCA (Acros Organics). Mass spectra were recorded with a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight, time of flight (MALDI-TOF-TOF) spectrometer (4800 Proteomics Analyzer, Framingham, MA) set in reflector positive mode after spotting the samples onto a MALDI plate. Peptide masses were compared with the theoretical masses derived from the sequences contained in SWISS-PROT/NCBI databases using MASCOT.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)—Protein-protein interaction of hBP3 and FGF2 was determined by solidphase immunoassays using microtiter polyvinyl chloride plates (Maxisorb, Nunc). A sandwich ELISA was carried out by coating the plates with purified hBP3 (100 μl; see Fig. 1B) per well. After blocking with 5% dry milk in PBS/0.05% Tween, FGF2 (100 ng) was added to each well and then detected using a monoclonal FGF2 antibody and goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody.

FIGURE 1.

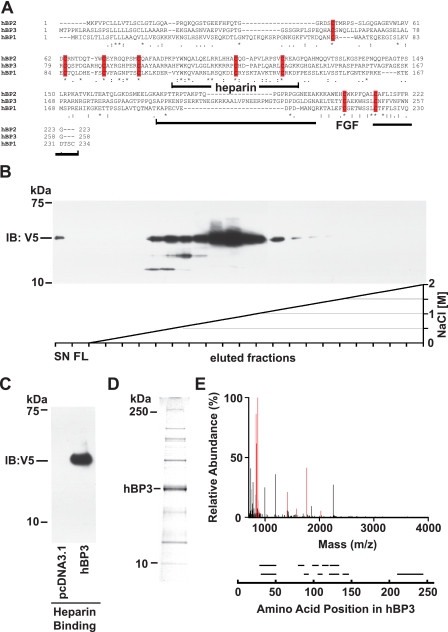

Human BP3 sequence comparison, protein purification, and protein identification. A, amino acid sequence alignment of human BP1, -2, and -3 proteins (GenBank™: NP_005121, NP_114156, and NP_689642, respectively). The BP protein family conserved domain is PFAM_06473. Identical (*) and conserved (: or.) amino acids as well as conserved cysteine residues (red bars) are indicated. The heparin binding and the C-terminal FGF binding domains in BP1 (41) as well as the corresponding portions of BP3 are indicated. B and C, heparin binding of hBP3 harvested from conditioned media of transfected HEK293T cells. Heparin affinity chromatography on HiTrap FPLC colums using an NaCl gradient as indicated (C) and batch elution from heparin-Sepharose with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (D) are shown. Supernatants from cells transfected with a hBP3-V5/His expression vector (for 72 h) were loaded onto column that contains immobilized heparin as an affinity matrix. Eluted hBP3 was detected by immunoblotting (IB) for V5. SN, supernatant; FL, flow. D, Coomassie Blue staining of proteins in the peak elution fractions of hBP3 in panel B. The indicated band matched with the migration of immunoreactive hBP3 and was excised for mass spectrometry analysis. E, mass spectrometry analysis identified eleven peptides matching with hBP3 by peptide mass fingerprinting (in red). Peptide fragments identified by sequencing are shown aligned with their positions in the hBP3 protein.

Immunocytochemistry—For visualization of proteins in in vivo studies, blood vessels were microinjected with 4% formaldehyde. Fixed tissues were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.18% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Fixed cells were stained with primary antibodies for 1 h and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG for 30 min. Images were taken with a Nikon SMZ-1500 epifluorescence digital stereomicroscope.

Microinjection of Embryos—The allantoic sac injection was described previously (28). For injection into vitelline veins and measurement of vascular permeability, 100 μl of the Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)/DNA mixture or 1 mg/ml dextran-FITC in PBS or 0.1 μg of PD173074 (Calbiochem) in PBS were microinjected into anterior or posterior vitelline vein of 3-day-old chicken embryos, using a microperfusion system with glass capillaries (Vestavia Scientific, Birmingham, AL).

Data Analysis—Prism 5 (Graph-Pad Inc) software was used for graphing and for statistical comparisons across different data sets by Kaplan-Meier, analysis of variance or Student's t test as appropriate. p values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

In Silico Analysis of hBP3—A BLAST search with human fibroblast growth factor-binding protein 1 (hBP1, accession number NP_005121) showed 23% identity to hBP2 (NP_114156) over 186 amino acids (aa 42–227 of hBP1), and 24% identity to hBP3 (NP_689642) over 173 amino acids (aa 55–227 of hBP1). The alignment of hBP1, 2 and 3 by ClustalW shows that the spacing of 8 cysteine residues is conserved among the three BPs (Fig. 1A), which suggests that they may form similarly patterned disulfide bridges first described in a structural analysis of bovine BP1 protein isolated from prepartum mammary glands (36). Also, the BP protein family has been assigned a conserved domain (CD) structure (PFAM06473, FGF-BP1), and hBP3 matched with the requirements of this CD.

hBP3 Is Secreted and Binds to Heparin—Hydropathy plot analysis revealed one strongly hydrophobic region at the N terminus of hBP3, and a secretory signal sequence was predicted with a cleavage site between position 26 (A) and 27 (R) using the SignalP 3.0 Server. Indeed, hBP3 was found to migrate at an apparent molecular mass of 37 kDa on SDS-PAGE using supernatants of HEK293T cells transfected with an expression vector that contains the hBP3 protein C-terminally tagged with a V5/His tag (Fig. 1, B–D). To assess binding of hBP3 to glycosaminoglycans originally described for BP1 (11), conditioned media from transfected HEK293T cells were loaded onto chromatography columns containing immobilized heparin, and hBP3 protein was eluted using a linear NaCl concentration gradient from 0 to 2.0 m (Fig. 1B). The elution peak of V5/His tagged hBP3 was at 0.7–0.9 m NaCl, similar to hBP1 (27). This elution profile from heparin positions BPs between low affinity heparin binding growth factors such as PDGF (elution around 0.5 m NaCl, Ref. 42) and FGF2, which elutes around 1.5 m NaCl (see Fig. 2C and Refs. 42, 43).

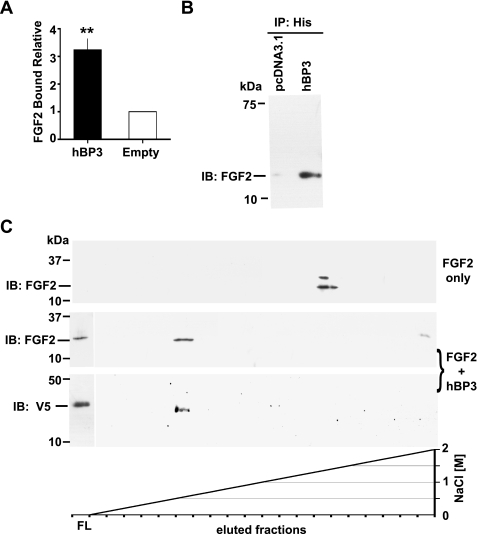

FIGURE 2.

hBP3 interaction with FGF2 and heparin. A, FGF2 binding to immobilized hBP3. hBP3 purified by heparin affinity (see Fig. 1D) or control media were immobilized in 96-well plates and then incubated with FGF2. After washing, bound FGF2 was detected by a mouse monoclonal antibody and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Binding relative to control is shown (mean ± S.E.; **, p < 0.01). B, interaction of hBP3 with endogenous FGF2. Anti-His antibody immunoprecipitation (IP) of proteins in supernatants from hBP3-V5/His or empty vector (pcDNA3.1) transfected 293T cells were immunoblotted for FGF2 to detect the interaction of hBP3 with endogenous FGF2. C, impact of hBP3 on FGF2 binding to heparin. FGF2 (1 μg) alone or a mixture of FGF2 plus an excess of hBP3 were loaded onto heparin affinity columns and bound proteins eluted by increasing concentrations of NaCl. FGF2 and hBP3 were detected by immunoblotting of aliquots. FGF2 only: in the absence of hBP3, FGF2 bound tightly to heparin and eluted at high salt concentrations (>1.5 m NaCl). FGF2 plus hBP3: As a complex, both proteins bound poorly to heparin and were mostly found in the flow (FL) from the column, although a smaller portion of FGF2 eluted with hBP3 at low salt concentrations (0.6 to 0.8 m NaCl).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of hBP3 Protein—To further analyze the hBP3 protein, the peak elution fractions from heparin affinity chromatography of hBP3 (Fig. 1B) were separated on a 4–12% NUPAGE gel and proteins stained with Coomassie Blue. The predominant protein present in this fraction migrated at the same position as immunoreactive hBP3 (Fig. 1D). This protein band was excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 1E). 11 peptides, including the four most abundant peptides, were identified as hBP3 by peptide mass fingerprinting and MS/MS sequence analysis. The peptides identified are shown aligned with the corresponding portion of hBP3 (Fig. 1E, bottom panel) and cover 43.8% of the hBP3 protein. No post-translational modifications of the secreted protein were apparent from this analysis.

Binding of hBP3 to FGF2—To determine the binding of hBP3 to FGF2, heparin affinity FPLC-purified hBP3 or control media were immobilized on 96-well plates and incubated with FGF2. The bound FGF2 was then detected by ELISA. FGF2 binding was >3-fold higher with hBP3 present (Fig. 2A, p < 0.001) suggesting a direct interaction between hBP3 and FGF2. In addition to this in vitro assay, the interaction of hBP3 with endogenous FGF2 was also examined in intact cells. Analysis of hBP3 immunoprecipitates from conditioned media revealed that FGF2 was associated with hBP3 present in the transfected cell supernatants (Fig. 2B). The hBP3/FGF2 association was also found when HEK293T cell lysates were co-immunoprecipitated for FGF2 and immunoblotted for the V5-tagged hBP3 (not shown). We conclude from this that hBP3 can bind to and mobilize cell-associated FGF2.

Interaction of hBP3, FGF2, and Heparin—FGF2 is stored on glycosaminoglycans in the extracellular matrix and this interaction is also reflected in its tight binding to immobilized heparin, a property that was crucial in the initial isolation of FGF2 by heparin affinity chromatography (42, 43). As described in these earlier reports, recombinant FGF2 protein bound tightly to immobilized heparin and was eluted at >1.5 m NaCl (Fig. 2C, FGF2 only). In contrast, when FGF2 was preincubated with an excess of hBP3, the majority of both FGF2 and hBP3 were found in the flow from the column. A small portion of both proteins eluted at 0.6–0.8 m NaCl (Fig. 2C, FGF2+hBP3). The interaction of hBP3 and FGF2 present in the flow from the heparin affinity chromatography was further confirmed by immunoprecipitation for FGF2 and immunoblotting for V5 (not shown). From these experiments, we conclude that hBP3 binds to FGF2 and that this interaction reduces the binding affinity of either of the proteins for heparin likely due to steric hindrance of their respective heparin binding sites.

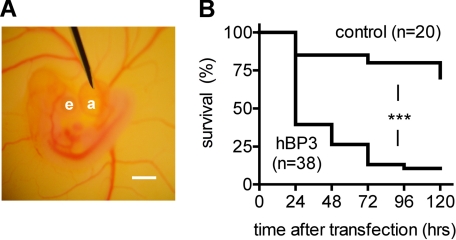

Expression of hBP3 via Allantoic Sac Injection Decreases the Survival Rate of Chicken Embryos—To examine the functional role of hBP3 in vivo, we transfected chicken embryos with 4 μg of hBP3-V5/His by microinjection into the allantoic sac from which the Lipofectamine-DNA complex is absorbed into the embryo (28). The position of the injection needle is shown in Fig. 3A. Quite strikingly, 60% of hBP3-transfected embryos died within the first 24 h after transfection (Fig. 3B). The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed a significant difference between the hBP3 and the control (pcDNA3.1) group over the 5-day observation period (p < 0.0001).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of hBP3 expression in chicken embryos. A, placement of the injection needle into the allantoic sac of a 4-day-old embryo. e, eye; a, allantoic sac; scale bar, 1 mm. B, survival rates of embryos (+S.E.) injected with 4 μg of control (pcDNA3.1) or hBP3 expression vector DNA. ***, p < 0.0001, control versus hBP3.

Gene Expression in 3-Day-Old Chicken Embryos by Microperfusion of the Vitelline Vein—To explore the mechanism by which hBP3 caused embryonic lethality, we established transient transfection of the embryo vascular system in which the DNA-Lipofectamine complexes are delivered by microperfusion of the anterior or posterior vitelline vein of day 3 chicken embryos. For this, a glass pipette tip (<70 μm in diameter) was inserted into the vitelline vein (80–90 μm in diameter) using a micromanipulator, and 4 μg of DNA were delivered into each embryo. Fig. 4A shows the position of the pipette filled with Trypan Blue for better visibility. When a GFP-expressing plasmid was delivered into the circulation by microperfusion, the expression of GFP was detected in live embryos as early as 8 h after transfection (not shown), and we used this time point in further gene expression studies.

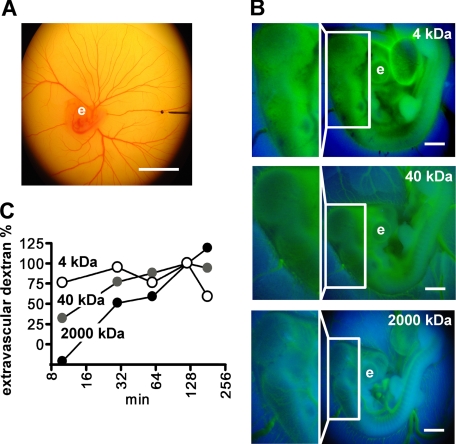

FIGURE 4.

Microperfusion of chicken embryos and assessment of vascular permeability. A, a glass pipette filled with Trypan Blue is positioned in a vitelline vein (80 μm in diameter) for microperfusion of a 3-day-old embryo. Scale bar, 10 mm. B, dextran-FITC of different molecular mass was microper-fused into embryos and fluorescence images (excitation wave length, 485 nm) were taken at different times for quantitation of extravasated dextran. A representative set of images of the embryos 10 min after injection of dextrans is shown. The boxed areas are also shown at higher magnification. Note that 4-kDa dextran extravasates at the earliest time point observed. e, eye; scale bar, 1 mm. C, assessment of vascular permeability. The time course of extravasation of the different dextrans was assessed by image analysis and is shown relative to the value reached after 120 min. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown.

Assessment of Vascular Permeability by Monitoring the Flux of Dextran-FITC into the Extravascular Space—According to Fick's law, the flux of a certain substance is mainly determined by the vascular permeability of that substance if the total vascular surface area and the concentration gradient of that substance across the capillary wall are the same. Assuming that the total vascular surface area is the same among day 3 chicken embryos and the initial concentration gradient is identical, the vascular permeability can be estimated by assessing the flux rate. FITC-labeled dextrans of different mass were used to estimate the baseline vascular permeability. Microperfusion of the vitelline vein with 0.1 mg of FITC-labeled dextrans of 2000, 40, or 4 kDa was followed by fluorescence imaging (excitation wavelength of 485 nm) at different time intervals.

The 2000-kDa dextran marks the outline of major blood vessels in the embryos 10 min after microperfusion and a cranial area without large vessels shows low fluorescence (boxed area in Fig. 4B, bottom panel). After 120 min, the vessel outline becomes blurred and the 2000-kDa dextran is also found in the extravascular area (not shown). In contrast, for the 4-kDa dextran, no distinct blood vessels were seen even at the 10-min time point, and this dextran was also distributed into the extravascular area and over the whole embryo at the earliest time point (Fig. 4B, top panel). The 40-kDa dextran was inbetween and the vessel outline was blurred at 10 min with an even distribution of fluorescence over the embryo, reaching steady-state at 120 min (Fig. 4, B, middle panel and C). Quantification of the difference between green (FITC) and blue (background) fluorescence at different time intervals shows that the embryonic blood vessels have no barrier function for the smallest dextran of 4 kDa, have lower permeability for the 40 kDa, and the lowest for the 2000-kDa dextran species. This result establishes and validates the approach for monitoring and quantifying vascular permeability in vivo.

Impact of hBP3 Expression on Vascular Permeability—To assess the impact of hBP3 on vessel function, the His/V5-tagged protein was expressed by microperfusion of chicken embryos with the hBP3 expression vector. Protein expression in embryos was detectable as early as 8 h after transfection by immunoprecipitation of embryo lysates with anti-His antibodies followed by immunoblotting for V5 (Fig. 5A). hBP3 protein expression was also detectable by immunofluorescence microscopy at this time point (not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Increase of vascular permeability by hBP3 expression and reversal by an FGFR kinase inhibitor, PD173074. A, detection of hBP3 protein in chicken embryo lysates. Eight hours after microperfusion with a control (pcDNA3.1) or the hBP3-V5/His expression vector, hBP3 was immunoprecipitated with anti-His antibodies and detected by immunoblot for V5. B, extravasation of 40-kDa dextran-FITC in chicken embryos expressing a control vector (pcDNA3.1; n = 4) or hBP3 without (n = 5) or with FGFR inhibitor PD173074 pretreatment (n = 3; 1 mg/kg systemically perfused 1 h before transfection). Dextran-FITC 40 kDa was injected 8 h after transfection, and representative fluorescence images, taken 10 min after dye injection, are shown. The boxed areas are used to monitor dye extravasation and are also shown magnified. e, eye; scale bars, 1 mm. C, quantitation of extravascular dextran-FITC at different time points after dye injection. ***, p < 0.001 and **, p < 0.01 hBP3 versus control or versus hBP3+PD173074, respectively.

Vascular permeability in control and hBP3-expressing embryos was monitored using 40-kDa dextran-FITC that was delivered into the vitelline vein. The outline of major blood vessels was clear and sharp in the pcDNA3.1-transfected embryos, and only little dextran-FITC was observed in the extravascular area at the 10-min time point (Fig. 5B, pcDNA3.1; Fig. 5C, open circles). In contrast, in the hBP3-transfected embryos, the outline of major vessels was blurred and significantly more dextran-FITC was found in the extravascular region at 10 min (p < 0.001) and 30 min (p < 0.01). Thus, vascular permeability was significantly higher after hBP3 expression in the embryos. It is noteworthy that at 120-min dextran-FITC was evenly distributed inside and outside the vasculature in both groups and is thus a useful internal loading control (Fig. 5C).

Effect of PD173074, a FGF Receptor Kinase Inhibitor on hBP3-induced Vascular Leakage—To assess the contribution of FGF receptor signaling to the increase in vascular permeability, we pretreated the chicken embryos with 1 mg/kg of PD173074 (38–40) by injection into the vitelline vein 1 h before transfection with hBP3. Eight hours after transfection, the flux rate of 40-kDa dextran-FITC was evaluated. At 10 min after injection, the outline of major blood vessels was clear and sharp in the PD173074-pretreated group, but blurred in the untreated group (Fig. 5B). The extravascular flux of 40-kDa dextran-FITC was significantly higher in hBP3-transfected embryos than in the PD173074-pretreated hBP3 group (Fig. 5C). Most strikingly, for the PD173074 pretreated, hBP3-transfected group, the percentage of extravascular dextran was indistinguishable from that of the control transfected group (Fig. 5C). Obviously, the hBP3-induced vascular leakage was completely prevented by PD173074 treatment. We conclude that FGF receptor signaling is rate-limiting for hBP3-induced vascular leakiness.

Expression of the C-terminal FGF Binding Domain of hBP3—From the alignment of human BP1, -2, and -3 proteins, a C-terminal 66-amino acid fragment of hBP3 (C66) corresponds to the recently identified FGF binding domain in BP1 (41) that is distinct from and non-overlapping with the heparin binding domain (see Fig. 1A). To evaluate the relative contribution of the predicted FGF binding domain of hBP3 to the induction of vascular leakage, we generated a C66 expression vector. The cDNA coding for C66 was inserted downstream of an N-terminal pFLAG-CMV vector that carries a secretory signal sequence to ensure release of the C66 peptide to the extracellular space. When expressed in HEK293T cells, C66-FLAG was detected in conditioned media by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting for FLAG (Fig. 6A). Expression of the control vector, pFLAG, gave no detectable signal. Obviously, C66-FLAG is processed appropriately and secreted from cells.

FIGURE 6.

In vitro and in vivo function of the hBP3 FGF binding domain. A, expression of the C-terminal hBP3 fragment that contains the predicted FGF binding domain (C66; see Fig. 1A) in HEK293T cells. Cells were transfected with pFLAG-CMV or C66-FLAG for 48 h and C66 detected by anti-FLAG immunoblot of cell supernatants after anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. B, heparin affinity chromatography of FGF2 mixed with C66. FGF2 (1 μg) was mixed with C66-FLAG-conditioned medium, and the mixture loaded onto a HiTrap heparin affinity column (see also Figs. 1B and 2B). Bound proteins were eluted by an NaCl gradient. In the presence of C66, FGF2 was not retained by the column and only detected in the flow (FL). C, effect of C66 on vascular permeability in the absence and presence of exogenous FGF2 protein. Chicken embryos were microperfused with a C66-FLAG or a control expression vector (pFLAG). Eight hours after transfection, vascular leakiness was assessed by injection of 40-kDa dextran-FITC without and with a 1-h pretreatment with FGF2 (0.1 μg of perfusion). Extravascular dextran at different time points after dye injection is shown. *, p < 0.05 C66+FGF2 versus pFLAG or C66 or pFLAG+FGF2 (n = 3 per group; analysis of variance).

Interaction of the C-terminal FGF Binding Fragment (C66), FGF2, and Heparin—Because the C66 fragment of hBP3 lacks the heparin binding domain of the full-length protein (see Fig. 1A), we studied, whether this fragment would still impact on the interaction of FGF2 with heparin. For this, FGF2 was mixed for 10 min with an excess of C66-FLAG harvested from transfected cell supernatants and then loaded onto a HiTrap heparin affinity column. To our surprise, the presence of C66 prevented FGF2 from binding to the immobilized heparin, and FGF2 was only detected in the flow from the column (Fig. 6B, FL). This supports the notion that binding of C66 to FGF2 sterically hinders the access of heparin to its binding residues in FGF2. This in vitro finding suggests that the bioavailability of exogenously administered FGF2 protein should be increased by the presence of C66. We tested this hypothesis in functional in vivo studies that are presented in the next section.

Effect of C66 Expression on Vascular Permeability Without and With Exogenous FGF2—Injection of a C66 expression vector into the allantoic sac of day 3 chicken embryos resulted in protein expression by immunofluorescence staining but did not induce increased embryonic lethality over a 5-day observation period (not shown). This is in contrast with the effect observed with full-length hBP3 (see Fig. 3B). The contribution of the FGF binding domain (C66) to hBP3-induced vascular leakage was thus assessed next. Surprisingly, vascular permeability was not changed in embryos expressing C66 for 8 h relative to controls (n = 3; Fig. 6C, pFLAG versus C66). From this, we hypothesized that this lack of an effect might be due to the reduced ability of the C66 fragment to release endogenously stored FGF. We thus also administered exogenous FGF2 one hour before the assessment of vascular permeability. The outline of major blood vessels became very blurred in embryos that received FGF2 and expressed C66 (Fig. 6C, C66+FGF2). For this group, the percentage of extravascular dextran was 91.0 + 5.3% 10 min after injection of the dye. This was significantly higher than the C66 group without FGF2 or the pFLAG group with or without FGF2 (n = 3, p < 0.05; Fig. 6C). We conclude from this data that C66 expression prevents the immobilization and inactivation of the exogenously administered FGF2 on HSPGs and thus supports the induction of vascular permeability by FGF2. However, in contrast to full-length hBP3, the C66 fragment appears unable to mobilize endogenous FGF and thus induce vascular leakage.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe human BP3 (hBP3) as a new member of the family of extracellularly secreted FGF-binding proteins, and analyze the interaction of hBP3 with FGF2 as well as heparin to shed more light on its mechanism of action. hBP3 heparin affinity chromatography was reminiscent of hBP1 in that elution from heparin binding occurs at intermediate NaCl concentrations that are significantly lower that those needed to elute FGF2. Quite surprisingly, the binding of FGF2 to the immobilized heparin was reduced dramatically by addition of full-length BP3 or of the C-terminal C66 fragment that contains the FGF binding domain. These findings support a mechanism of action whereby the secreted hBP3 protein functions as an extracellular chaperone for FGFs and prevents their immobilization on extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans.

The functional role of hBP3 in vivo was assessed in a transgenic chicken embryo model. In this model system, expression of hBP3 is lethal for >50% of the embryos within 24 h after initiation of transgene expression similar to our findings reported earlier for hBP1 (28). Here we describe a sensitive method to monitor vascular permeability by injection of FITC-labeled dextran and follow its extravasation kinetics. Surprisingly, increased vascular permeability is apparent within 8 h after hBP3 transgene introduction into the embryos. Furthermore, the effect of hBP3 on vascular permeability was prevented by short term pretreatment of embryos with the FGFR kinase inhibitor PD173074. This supports a specific effect of hBP3 through the FGF signaling pathway. The findings also demonstrate that the detection of vascular permeability in vivo is sensitive enough to monitor effects of transgenes (hBP3, C66), injected proteins (FGF2), drugs (PD173074), or combinations thereof.

Surprisingly, expression of the C-terminal 66 amino acids (C66) of hBP3 that contains the predicted FGF binding domain, required exogenously administered FGF2 protein to increase vascular permeability (Fig. 6C). This C66 fragment lacks the predicted heparin binding domain of the hBP3 protein, one of the conserved portions when comparing hBP3 and hBP1 (see Fig. 1A). Still, when added to FGF2, the C66 fragment prevented FGF2 from binding to immobilized heparin (Fig. 6B). This suggests to us that C66 functions in vivo by protecting exogenous FGF2 from binding to HSPG (Fig. 6C). However, the heparin binding domain in hBP3 appears to render the protein more efficacious in mobilizing endogenous FGFs from the HSPG storage.

Earlier studies with the C-terminal FGF binding domain of BP1 showed that this fragment enhanced FGF2 signaling in cultured cells (see also Ref. 41) similar to the present in vivo data with the hBP3-C66. From these findings, it is tempting to speculate that a fragment of either BP1 or BP3 that contains only the FGF binding domain could be used as a cofactor to enhance the biologic effect of exogenously administered FGF without interfering with endogenously stored FGFs.

The increase in vascular permeability observed after expression of hBP1 (28) or hBP3 (Fig. 5, B and C) is found in conjunction with diverse biologic processes including inflammation, angiogenesis (29), or tumor metastasis all of which impact on endothelial barrier function (44). Work from different laboratories has shown that BP1 interacts at least with FGF1, -2, -7, -10, and -22 (12–14), and it is conceivable that hBP3 may have a similar range of FGF partners as hBP1, though it is possible that the two proteins differ in their affinities or selectivity for distinct FGFs.

CONCLUSIONS

We describe the interaction of hBP3 with FGF2 and heparin and show its effect on vascular permeability and overall survival in chicken embryos. The studies with recombinant proteins show that heparin binding of FGF2 is inhibited by the full-length hBP3 protein as well as by a C-terminal fragment that only contains the FGF binding domain. These findings suggest that the binding site of hBP3 overlaps with the HSPG contact sites on the FGF molecule and the interaction with hBP3 will sterically hinder binding of FGF to heparin. In the presence of BP, the equilibrium will thus shift from FGFs immobilized on extracellular HSPGs toward FGFs released into solution in a complex with BP. The FGF mobilized from extracellular storage by BP (31) shows increased biologic activity (12) and can stimulate FGFR signaling independent of the presence of HSPGs (26). Overall, the expression levels of BP can thus control or fine-tune the biologic activity of locally stored FGFs as shown earlier for the BP1 role as an “angiogenic switch” molecule in cancer (31) that is up-regulated during oncogenesis (31–35), but can also be induced acutely in skin wounding (32, 34), or after spinal cord injury (45) to enhance the repair function of locally stored FGF.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Kencel (Georgetown University) for help with some of the experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA71508 (to A. W.) and P30 CA51008 from the NCI. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: FGF, fibroblast growth factor; hBP3, human FGF-binding protein 3; HSPG, heparan sulfate proteoglycan; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; GFP, green fluorescent protein; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

A. Wellstein, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Powers, C. J., McLeskey, S. W., and Wellstein, A. (2000) Endocr. Relat. Cancer 7 165-197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohammadi, M., Olsen, S. K., and Ibrahimi, O. A. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 107-137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eswarakumar, V. P., Lax, I., and Schlessinger, J. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 139-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Presta, M., Dell'Era, P., Mitola, S., Moroni, E., Ronca, R., and Rusnati, M. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 159-178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grose, R., and Dickson, C. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 179-186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkie, A. O. (2005) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16 187-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenman, C., Stephens, P., Smith, R., Dalgliesh, G. L., Hunter, C., Bignell, G., Davies, H., Teague, J., Butler, A., Stevens, C., Edkins, S., O'Meara, S., Vastrik, I., Schmidt, E. E., Avis, T., Barthorpe, S., Bhamra, G., Buck, G., Choudhury, B., Clements, J., Cole, J., Dicks, E., Forbes, S., Gray, K., Halliday, K., Harrison, R., Hills, K., Hinton, J., Jenkinson, A., Jones, D., Menzies, A., Mironenko, T., Perry, J., Raine, K., Richardson, D., Shepherd, R., Small, A., Tofts, C., Varian, J., Webb, T., West, S., Widaa, S., Yates, A., Cahill, D. P., Louis, D. N., Goldstraw, P., Nicholson, A. G., Brasseur, F., Looijenga, L., Weber, B. L., Chiew, Y. E., DeFazio, A., Greaves, M. F., Green, A. R., Campbell, P., Birney, E., Easton, D. F., Chenevix-Trench, G., Tan, M. H., Khoo, S. K., Teh, B. T., Yuen, S. T., Leung, S. Y., Wooster, R., Futreal, P. A., and Stratton, M. R. (2007) Nature 446 153-15817344846 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess, W. H., and Maciag, T. (1989) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58 575-606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bashkin, P., Doctrow, S., Klagsbrun, M., Svahn, C. M., Folkman, J., and Vlodavsky, I. (1989) Biochemistry 28 1737-1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlodavsky, I., Bashkin, P., Ishai-Michaeli, R., Chajek-Shaul, T., Bar-Shavit, R., Haimovitz-Friedman, A., Klagsbrun, M., and Fuks, Z. (1991) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 638 207-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu, D., Kan, M., Sato, G. H., Okamoto, T., and Sato, J. D. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 16778-16785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tassi, E., Al-Attar, A., Aigner, A., Swift, M. R., McDonnell, K., Karavanov, A., and Wellstein, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 40247-40253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mongiat, M., Taylor, K., Otto, J., Aho, S., Uitto, J., Whitelock, J. M., and Iozzo, R. V. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 7095-7100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beer, H. D., Bittner, M., Niklaus, G., Munding, C., Max, N., Goppelt, A., and Werner, S. (2005) Oncogene 24 5269-5277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aigner, A., Butscheid, M., Kunkel, P., Krause, E., Lamszus, K., Wellstein, A., and Czubayko, F. (2001) Int. J. Cancer 92 510-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mongiat, M., Otto, J., Oldershaw, R., Ferrer, F., Sato, J. D., and Iozzo, R. V. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 10263-10271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yayon, A., Klagsbrun, M., Esko, J. D., Leder, P., and Ornitz, D. M. (1991) Cell 64 841-848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoneda, A., Asada, M., Oda, Y., Suzuki, M., and Imamura, T. (2000) Nat. Biotechnol. 18 641-644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballinger, M. D., Shyamala, V., Forrest, L. D., Deuter-Reinhard, M., Doyle, L. V., Wang, J. X., Panganiban-Lustan, L., Stratton, J. R., Apell, G., Winter, J. A., Doyle, M. V., Rosenberg, S., and Kavanaugh, W. M. (1999) Nat. Biotechnol. 17 1199-1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogura, K., Nagata, K., Hatanaka, H., Habuchi, H., Kimata, K., Tate, S., Ravera, M. W., Jaye, M., Schlessinger, J., and Inagaki, F. (1999) J. Biomol. NMR 13 11-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plotnikov, A. N., Schlessinger, J., Hubbard, S. R., and Mohammadi, M. (1999) Cell 98 641-650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlessinger, J., Plotnikov, A. N., Ibrahimi, O. A., Eliseenkova, A. V., Yeh, B. K., Yayon, A., Linhardt, R. J., and Mohammadi, M. (2000) Mol Cell 6 743-750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellegrini, L., Burke, D. F., von Delft, F., Mulloy, B., and Blundell, T. L. (2000) Nature 407 1029-1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellegrini, L. (2001) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11 629-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason, I. (2007) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 583-596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray, P. E., Tassi, E., Liu, X. H., and Wellstein, A. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 290 R105—R113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czubayko, F., Smith, R. V., Chung, H. C., and Wellstein, A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 28243-28248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonnell, K., Bowden, E. T., Cabal-Manzano, R., Hoxter, B., Riegel, A. T., and Wellstein, A. (2005) Lab. Investig. 85 747-755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dvorak, H. F. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162 1747-1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rak, J., and Kerbel, R. S. (1997) Nat. Med. 3 1083-1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Czubayko, F., Liaudet-Coopman, E. D., Aigner, A., Tuveson, A. T., Berchem, G. J., and Wellstein, A. (1997) Nat. Med. 3 1137-1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurtz, A., Darwiche, N., Harris, V., Wang, H. L., and Wellstein, A. (1997) Oncogene 14 2671-2681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray, R., Cabal-Manzano, R., Moser, A. R., Waldman, T., Zipper, L. M., Aigner, A., Byers, S. W., Riegel, A. T., and Wellstein, A. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 8085-8089 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurtz, A., Aigner, A., Cabal-Manzano, R. H., Butler, R. E., Hood, D. R., Sessions, R. B., Czubayko, F., and Wellstein, A. (2004) Neoplasia 6 595-602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tassi, E., Henke, R. T., Bowden, E. T., Swift, M. R., Kodack, D. P., Kuo, A. H., Maitra, A., and Wellstein, A. (2006) Cancer Res. 66 1191-1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lametsch, R., Rasmussen, J. T., Johnsen, L. B., Purup, S., Sejrsen, K., Petersen, T. E., and Heegaard, C. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 19469-19474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aigner, A., Malerczyk, C., Houghtling, R., and Wellstein, A. (2000) Growth Factors 18 51-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skaper, S. D., Kee, W. J., Facci, L., Macdonald, G., Doherty, P., and Walsh, F. S. (2000) J. Neurochem. 75 1520-1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohammadi, M., Froum, S., Hamby, J. M., Schroeder, M. C., Panek, R. L., Lu, G. H., Eliseenkova, A. V., Green, D., Schlessinger, J., and Hubbard, S. R. (1998) EMBO J. 17 5896-5904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bansal, R., Magge, S., and Winkler, S. (2003) J. Neurosci. Res. 74 486-493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie, B., Tassi, E., Swift, M. R., McDonnell, K., Bowden, E. T., Wang, S., Ueda, Y., Tomita, Y., Riegel, A. T., and Wellstein, A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 1137-1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shing, Y., Folkman, J., Sullivan, R., Butterfield, C., Murray, J., and Klagsbrun, M. (1984) Science 223 1296-1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gospodarowicz, D., Cheng, J., Lui, G. M., Baird, A., and Böhlen, P. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81 6963-6967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bazzoni, G., and Dejana, E. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84 869-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tassi, E., Walter, S., Aigner, A., Cabal-Manzano, R. H., Ray, R., Reier, P. J., and Wellstein, A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293 R775-R783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]