Abstract

Differential binding between cadherin subtypes is widely believed to mediate cell sorting during embryogenesis. However, a fundamental unanswered question is whether cell sorting is dictated by the biophysical properties of cadherin bonds, or by broader, cadherin-dependent differences in intercellular adhesion or membrane tension. This report describes atomic force microscope measurements of the strengths and dissociation rates of homophilic and heterophilic cadherin (CAD) bonds. Measurements conducted with chicken N-CAD, canine E-CAD, and Xenopus C-CAD demonstrated that all three cadherins cross-react and form multiple, intermolecular bonds. The mechanical and kinetic properties of the heterophilic bonds are similar to the homophilic interactions. The thus quantified bond parameters, together with previously reported adhesion energies were further compared with in vitro cell aggregation and sorting assays, which are thought to mimic in vivo cell sorting. Trends in quantified biophysical properties of the different cadherin bonds do not correlate with sorting outcomes. These results suggest that cell sorting in vivo and in vitro is not governed solely by biophysical differences between cadherin subtypes.

Cadherins are cell-surface adhesion molecules that mediate calcium-dependent intercellular adhesion in all solid tissues. The importance of cadherins was recognized early on from the observation that the segregation of embryonic cells into distinct patterns correlated with the expression profiles of cadherin subtypes (1). Cadherins mediate cell sorting into distinct tissues during morphogenesis, and they organize boundaries in mature tissues (2–4). For example, neural cadherin (N-CAD)2 first appears during neurulation and is essential for the separation of the neural tube from the embryonic ectoderm, which expresses epithelial cadherin (E-CAD) (5). Blocking antibodies or ectopically expressed cadherins also cause major morphological defects during development (6–8).

Early studies suggested that cell-surface properties drive cell segregation. In vitro, dissociated amphibian embryonic cells re-aggregated and then sorted out to form tissue-like cell patterns (9). This behavior was linked to cadherins. Embryonic lung tissue was dissociated into mesenchymal and epithelial cells that express N-CAD and E-CAD, respectively. When re-aggregated, the epithelial and mesenchymal cells sorted out as in the original embryonic tissue. Similarly, L-cells transfected with E-CAD partitioned with the epithelial cells.

A fundamental question is whether cell sorting is dictated by differences in cadherin adhesion, and if so, whether the biophysical properties of the adhesive bonds dictate cell sorting. One widely held view is that selective homophilic versus heterophilic cadherin binding drives cell sorting. This was based on studies of selective cell segregation in agitated suspensions (10–13). In particular, cells expressing different cadherin subtypes formed segregated clusters when agitated for 45–60 min (10–12). Exchanging the N-terminal EC1 domains of different cadherin subtypes switched the cell aggregation specificity in those same assays (14). Alternatively, equilibrium models postulate that differences in intercellular adhesion energies (or interfacial tension) due to differential cadherin binding cause cells to sort out (15, 16). Recent findings indicate that cell surface tension, which depends on cadherin identity and density as well as on cortical tension, governs embryonic cell sorting (17).

Several findings differ from short term cell-sorting results, which were attributed to preferential homophilic cadherin binding. In alternative long term aggregation assays, Steinberg and co-workers (18) showed that cells expressing different cadherins formed intermixed cell clusters after ∼4 days. Furthermore, in flow assays, E-, N-, and C- (cleavage stage) cadherin-expressing cells adhered equally well to substrates coated with E-CAD ectodomains, although E-CAD- and N-CAD-expressing cells (E-CHO and N-CHO) formed separate clusters in short term aggregation assays (19). The measured adhesion energies of homophilic and heterophilic cadherin bonds are also similar (20). Consequently, cadherins appear to exhibit little binding selectivity.

Based on the degree of sequence and structural homology between classical cadherins, one might expect cross-reactivity between cadherin subtypes. The classical cadherins include an extracellular region, a single-pass transmembrane domain, and a cytodomain (3). The ectodomain folds into five tandemly arranged extracellular (EC) domains, numbered EC1 to EC5 from the N terminus (21, 22). X-ray structures show that the ectodomains can bind each other by inserting the conserved Trp2 residue of the EC1 domain of one protein into a hydrophobic pocket on EC1 of an opposed or adjacent cadherin (21, 23–25). Studies mapped both adhesion and binding selectivity to this EC1 domain (14, 25, 26).

However, independent biophysical approaches, including cell adhesion studies, show that multiple EC domains are required for the formation of strong adhesive bonds (27–31). Molecular force measurements, using two different experimental methods and carried out with different classical cadherin ectodomains, demonstrated that the EC12 fragments alone exhibit only weak bonds with fast dissociation rates (28, 29, 32, 33). The strongest adhesion requires the full ectodomain. Adhesion between cell pairs exhibits biphasic kinetics, which also requires the full cadherin ectomain (31). Both molecular force probe and cell adhesion kinetics further showed that the highest probability binding state and strongest adhesion require the third domain EC3 (27, 28, 31). The latter findings are important because they identify additional interactions and binding steps that affect intercellular adhesion and could also impact cell segregation.

Importantly, although proposed models for cell sorting are based on postulated differences in cell and/or cadherin adhesion, the majority of methods used to investigate cadherin-mediated adhesion and selectivity are not quantitative nor do they determine the relevant biophysical parameters needed to test definitively whether specific cadherin ectodomain properties are sufficient to drive cell segregation.

Here we describe studies that directly address this knowledge gap, by quantifying the mechanical strengths and dissociation rates of cadherin bonds at the single molecule level. This work extends previous near-equilibrium cadherin adhesion energy measurements (20) by quantifying the rupture forces and intrinsic dissociation rates of homophilic and heterophilic cadherin linkages. These studies are motivated in part by the hypothesis that either thermodynamic (15, 16, 34) or kinetic differences between homophilic and heterophilic cadherin bonds underlie cell sorting. Three types of classic cadherins were studied as follows: chicken N-CAD, canine E-CAD, and Xenopus C-CAD. The forces required to dissociate individual cadherin ectodomain bonds were measured with the atomic force microscope (AFM). The quantified bond parameters were compared with cell aggregation results and with previously reported adhesion energies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines, Protein Production, and Purification—The soluble Fc-tagged full-length cadherin ectodomains were expressed in stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO K1) cells and purified as described (20, 27, 31). CHO-K1 cells expressing the full-length ectodomain of Xenopus C-CAD fused at the C terminus to the human Fc domain were cultured in Glasgow modified Eagle's medium containing 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum. CHO-K1 cells stably expressing wild type cadherin were similarly cultured in Glasgow modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human embryonic kidney cells (293HEK) expressing canine E-CAD (with a C-terminal Human Fc domain) or chicken N-CAD ectodomains (with a C-terminal mouse Fc domain) were cultured in modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. During the protein collection phase, the culture medium was switched to serum-free modified Eagle's medium to simplify the purification and increase protein yield.

Cadherins were purified from the serum-free, conditioned medium with a protein-A Affi-Gel affinity column (Bio-Rad). Further gel filtration chromatography was used when necessary. The protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

Short Term Cell Aggregation Assay—The cell aggregation assays were performed as described (10, 19, 36). Briefly, the cells were detached from the culture plates with 0.01% v/v trypsin (Invitrogen) in Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1 mm CaCl2 and 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The cells were washed and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution with 0.5 mm EDTA and 2% BSA. They were stained with the membrane dyes DiI and DiO (Molecule Probes, Eugene, OR), rinsed, and then resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 1 mm CaCl2 and 2% BSA to give 2 × 104 cell/ml. In 24-well plates, 0.5 ml of each cell population were mixed, and the plates were agitated in the water bath shaker (37 °C) at 160 rpm for 1 h. The cells were then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and imaged with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M fluorescence microscope (Thornwood, NY).

Long Term Cell Aggregation Assay—The preparation of cell aggregates for sorting followed published procedures (18). Briefly, CHO cells with similar cadherin expression levels were detached from the culture plates with trypsin in calcium-containing medium (10). Cells were labeled with fluorescent dye (DiI or DiO; Molecule Probes). The cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 cell/ml with PBS supplemented with 2% BSA and 2 mm CaCl2. A 10-μl aliquot of each of the two types of cadherin-expressing cells was mixed on the top lid of the 10-cm Petri dish. The lower dish contained 10 ml of PBS (Invitrogen). The hanging drops were placed in an incubator at 37 °C and maintained under 5% CO2 for 24 and 48 h. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and the aggregates were imaged.

Quantifying Cadherin Surface Density on CHO Cells—The cadherin density on the cell surface was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. The C-CAD-expressing CHO cells were stained with anti-C-CAD antibody (1 μg/ml) and then with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibody (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The solution was PBS containing 0.5 mm EDTA and 1% BSA at 4 °C. The fluorescence intensity of labeled cells and fluorescent bead standards were quantified with an LSR flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) (37). The fluorescence intensity was compared with calibrated fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled standard beads (Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN).

The E-CHO cells were stained with anti-E-CAD antibody (BD Biosciences) and then with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in PBS with 0.5 mm EDTA and 1% BSA at 4 °C. The N-CHO were stained with anti-N-CAD antibody (Sigma) and then with PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse antibody in PBS with 0.5 mm EDTA and 1% BSA at 4 °C. The fluorescence was compared against PE-Cy5-labeled standard beads.

Whole Cell Lysate Preparation and Immunoblotting—Cells were analyzed for relative amounts of cadherin expression by immunoblotting. The cadherin expression was normalized relative to β-actin. In addition, cadherin expression was compared with β-catenin (19). Briefly, cadherin-expressing CHO cells were lysed with “lysis buffer” (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixture from Roche Applied Science). Solutions were clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. The total protein concentration in the lysates was determined with the BCA protein assay (Pierce). Immunoblotting was performed with the same total amount of lysate protein from each cadherin-expressing cell line. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5% bisacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) and then transferred to a Hybond ECL membrane (GE Healthcare). The relative amount of cadherin, β-actin, and β-catenin was determined by immunoblotting with the corresponding primary antibodies and peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immunoblot signals were then quantified by densitometry with the Quantity One Analysis Software (Bio-Rad).

Antibodies—The monoclonal N-cadherin antibody, β-actin antibody, goat anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated antibody, goat anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated antibody, and mouse anti-goat peroxidase-conjugated antibody were from Sigma. The β-catenin antibody was from BD Biosciences, and the goat anti-C-cadherin and anti-E-cadherin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

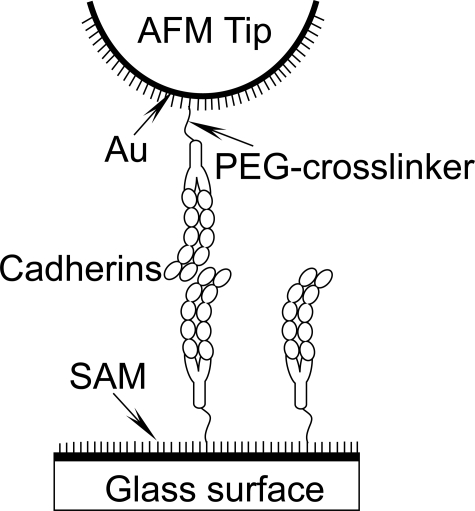

AFM Sample Preparation and Surface Chemistry—The surface modification of AFM cantilever tips and glass substrates (Fig. 1) was done exactly as described (38). Cantilevers (VeecoProbes, CA) and small glass slides (Fisher) were coated with a 60-nm layer of gold. A monolayer of 1,8-octanedithiol (Sigma) and 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (Sigma) was then self-assembled onto the gold films. Changing the ratio of the two thiol compounds changed the protein density on the surfaces. The monolayers were then activated with poly(ethylene glycol)-α-maleimide, ω-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (NHS-PEG-MAL-3400 Da, Nektar Therapeutics, Huntsville, AL). The maleimide group (MAL) reacts with exposed thiols on the 1,8-octanedithiol monolayer, and the exposed NHS group covalently binds free amines on proteins.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of cadherin ectodomains immobilized on the modified cantilever tip and glass slide. The self-assembled monolayer (SAM) was formed on the thin gold films and activated with the MAL-PEG3400-NHS linker. The NHS moiety covalently bound cadherins via free amines. Details of the cantilever and glass slide modification and cadherin immobilization procedures are given in the text.

A small Teflon fluidic cell was designed for the AFM to accommodate the sample and to enable it to be rinsed through two ports on the sides of the cell. Before incubating the tip and sample with protein solution, the glass slide was glued to the cell with epoxy. The sample was then mounted onto the AFM stage and incubated with protein solution (0.3 μm cadherin in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The cantilever was placed in the AFM cantilever holder and immersed in protein solution. The working buffer contained 100 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, and 2 mm CaCl2 (Fisher). Prior to force measurements, the cell was flushed several times with calcium-free buffer to remove noncovalently bound cadherin.

AFM Measurements—The bond rupture forces were measured with the molecular force probe 1-D (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) using Igor Pro software (WaveMetrics, OR) for data acquisition and piezo control. The optical lever sensitivity was calibrated by pressing the tip against a hard surface to give the tip deflection in nanometers. The spring constant kc of the gold-coated cantilevers was calibrated with the thermal method (39), and typical values were 10–25 pN/nm.

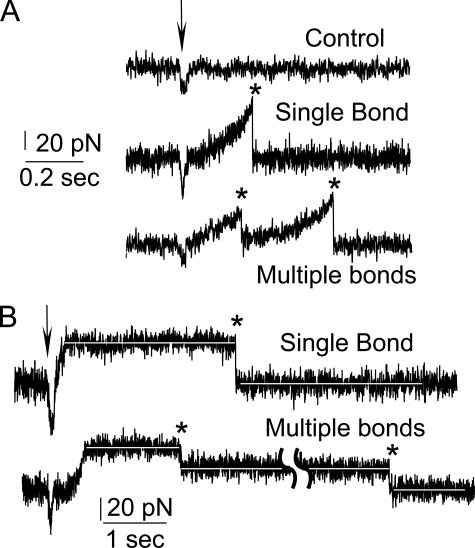

During the experiment, the fluidic cell was glued to a glass slide and attached to the molecular force probe stage by two magnets to stabilize the sample. A user panel with feedback control was written to drive the piezo in both the steady ramp and constant force modes (Fig. 2). The impingement forces were kept at ∼30 pN to reduce nonspecific adhesion between the surface and cantilever tip.

FIGURE 2.

Force time traces of AFM profiles obtained with the steady ramp mode (A) and the constant force mode (B). A, first curve shows a typical force trace in control measurements in which there is no adhesion. The arrow indicates initial tip-surface contact, and the asterisk indicates bond rupture. The middle curve shows a single bond rupture event, and the lower curve shows multiple-bond rupture. B, the force rapidly jumps to a preset value, which is held until the bond fails (asterisk). The duration of the flat, constant force region is the lifetime. The upper trace exhibits a single-bond rupture event, and the lower curve shows a rare case with the sequential rupture of two bonds.

Force measurements were conducted in two ways (Fig. 2). First, we used a steady force ramp, where the cantilever was brought into contact with the surface and then retracted at a constant velocity (Fig. 2A). Three to four thousand force curves were recorded at each loading rate. The binding frequency was adjusted to 10–30%, by controlling the cadherin density on the tip and substrate. In other words, less than 30 out of 100 touches to the surface generated an adhesion event. This increases the likelihood that most of the binding events were from single bonds. Force curves were analyzed with a custom-written program. For each force extension profile displaying a single rupture event (Fig. 2A, middle curve), the rupture force and the effective loading rate were both determined. The “effective loading rate” is the actual loading rate on the bond, determined from the elastic stretch region of the flexible PEG tethers. The slope of the latter curve just prior to bond rupture determines the effective spring constant keff. Thus, the effective loading rate at rupture is keffv, where v is the cantilever velocity. This differs from the “nominal loading rate,” which is ksv, where ksv is the cantilever spring constant. These analyses included only the force curves in which the relative standard deviation (S.D. divided by the mean) of the loading rates was less than 20%. Histograms were then constructed of the rupture forces measured at each loading rate.

The second type of measurement determined the bond lifetimes using the constant force mode. In this case, the force is set to a preset value and then maintained until the bond fails (Fig. 2B) (33, 40). The persistence time of the bond gives the lifetime under a set force (Fig. 2B).

To ensure that the results were independent of the immobilization, different cadherins were bound to the tip or to the substrate. Results obtained with N-CAD on the tip and E-CAD on the substrate, for example, were identical to data obtained with E-CAD on the tip and N-CAD on the substrate.

Data Analysis—According to Bell's model (41), the bond dissociation rate increases exponentially with an applied force, according to Equation 1,

|

(Eq. 1) |

Here koff is the intrinsic dissociation rate of the unstressed bond. The so-called thermal force fβ = kT/Xβ, where Xβ is the projection of the transition state along the force vector. kT is the thermal energy where k is Boltzmann's constant and T is the absolute temperature. When the force increases linearly with time, the rupture force distribution p(f) at loading rate rf (42) is shown in Equation 2,

|

(Eq. 2) |

The most probable force (MPF), defined by the maximum in the force distribution, is as shown in Equation 3,

|

(Eq. 3) |

For a bond confined by a single barrier, the MPF increases linearly with the logarithm of the loading rate. The parameters fβ and koff are obtained from MPF versus log(rf) plots.

In the lifetime measurements, when the force f is constant, the bond survival probability P(t) is (29, 33) as shown in Equation 4,

|

(Eq. 4) |

Here A is the probability amplitude, and kfoff is the dissociation rate of the bond subject to a constant force. For N bound states each with a dissociation rate ki, P(t) would be described by a sum of N exponentials. Fits of Equation 4 (or a superposition of exponentials) to plots of the survival probability versus time at a constant force fi give the number of bound states with rupture forces greater than fi and the dissociation rates. The dissociation rates are related to the lifetimes ti by ti = 1/ki.

RESULTS

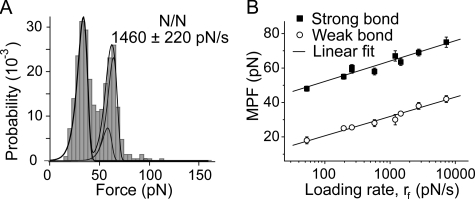

Homophilic Cadherin Bonds Exhibit Similar Strengths and Dissociation Rates—We measured homophilic binding between the Fc-tagged extracellular domains 1–5 of three classical cadherins: namely, chicken N-CAD, Xenopus C-CAD, and canine E-CAD. Fig. 3 summarizes the results of measurements with N-CAD. Rupture forces were measured at nine different loading rates, ranging from 10 to 104 pN/s. Fig. 3A shows the force histogram measured at the constant, effective loading rate of 1460 ± 220 pN/s. The bin size for the histogram in Fig. 3A is 4–6 pN, but this depends on the loading rate (Fig. 3). The bin size h is estimated by minimizing the integral of the mean square errors (MSE) (43) and is approximated to be h = 3.5 × σ × n-1/2, where σ is the standard deviation of the distribution, and n is the total number of data points (n ∼ 400, in these studies).

FIGURE 3.

Adhesion measurements between N-CAD ectodomains. A, histogram of the rupture force distribution measured at rf = 1460 ± 220 pN/s. The two sub-states in the high force peak (>40 pN) were obtained from the lifetime measurements. B, force spectra (most probable force (MPF) versus log(rf) plots) of N-CAD bonds associated with the major peaks in A, and the linear fits (solid lines). The best fit parameters are fβ = 5.2 ± 0.5 pN and koff = 5 ± 3 × 10-4 s-1 for the strong state. fβ = 4.8 ± 0.3 pN and koff = 0.2 ± 0.1 s-1 for the weak state. These parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Visual inspection of the histograms suggests that there are two principal peaks, which both shift to higher forces with increasing loading rate (Fig. 3B). To first approximation, the data can be described by a two-state probability distribution, which assumes a weak and a strong bond. The maxima correspond to the most probable rupture force (MPF) for each bond. For each peak, plots of the MPF versus log(rf), are linear (Fig. 3B). The error in the MPF determination was estimated from the variation of the determined value of the MPF that results from changing the start point of the histogram.

These studies used Fc-tagged cadherin ectodomains, which are expressed as dimers. Results from prior single molecule studies with Fc-tagged C-cadherin (33) were very similar to measurements with monomeric His6-tagged mouse E-cadherin (29). Nevertheless, we compared the force distributions of His6-C-CAD with those of Fc-tagged C-CAD to ensure that the dimerization did not alter the binding behavior. The force histograms measured with His6-C-CAD also exhibited two peaks. The only difference was that the amplitude of the low force peak (relative to the strong bond) was ∼30% larger than with Fc-C-CAD under similar measurement conditions.

To determine whether the broad distribution of rupture events at >40 pN are because of multiple, parallel tip-surface bonds rather than a single tip-surface linkage, we used a previously described approach (40). If the force is shared between N bonds, each bond experiences a force f/N, and the bonds fail randomly. In this case, the force distribution (Equation 2) is approximated, by replacing koff and fβ of the single bond by Nkoff and Nfβ, respectively (29, 40). We used the bond parameters obtained for the low force peak to calculate probability distributions for N, parallel, weak bonds, where n = 2, 3, or 4. The calculated probability distributions did not fit the second peak. This supports the conclusion that the two peaks in the distribution are independent, homophilic N-CAD bonds. Similar results were obtained with the other classical cadherins used in this study.

In Fig. 3B, the linear least squares fit of Equation 3 to the MPF versus log(rf) curves gave slopes of 12 ± 1 and 11.0 ± 0.7 pN, for the high and low force peaks, respectively. This corresponds to 0.8 ± 0.08 and 0.85 ± 0.05 nm for the respective values of xβ. The intrinsic dissociation rates, determined from the intercepts at MPF = 0, are 5 ± 3 × 10-4 and 0.2 ± 0.1 s-1 for the strong and weak bond, respectively. Fitted parameters obtained for the homophilic interactions between all three classical cadherins are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Dissociation rates and thermal forces of the cadherin bonds determined from linear fits to the force spectra

|

Strong bond

|

Weak bond

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| koff | fβ | koff | fβ | |

| s–1 | pN | s–1 | pN | |

| C-CAD/C-CAD | 3 ± 2 × 10–5 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 3 ± 0.3 |

| E-CAD/E-CAD | 4 ± 1 × 10–5 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.4 |

| N-CAD/N-CAD | 5 ± 3 × 10–4 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.3 |

| C-CAD/E-CAD | 9 ± 6 × 10–5 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 0.01 ± 0.005 | 3 ± 0.4 |

| E-CAD/N-CAD | 4 ± 1 × 10–4 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 8 ± 0.4 |

| C-CAD/N-CAD | 9 ± 8 × 10–3 | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 0.09 ± 0.06 | 4.3 ± 0.4 |

The use of EDTA in control measurements abolished binding and reduced the binding frequency (number of adhesion events/number of tip-surface contacts) to <2–3%, compared with 15–20% obtained with active protein. Furthermore, the forces were low and randomly distributed. The impingement force was kept <30 pN in all measurements, to minimize nonspecific binding.

In a previous study of cadherin bond rupture with the biomembrane force probe (BFP), the major peaks masked “hidden states” (29, 33). Here we used the force clamp (lifetime) measurements to determine whether the peaks in Fig. 3B similarly contain hidden states.

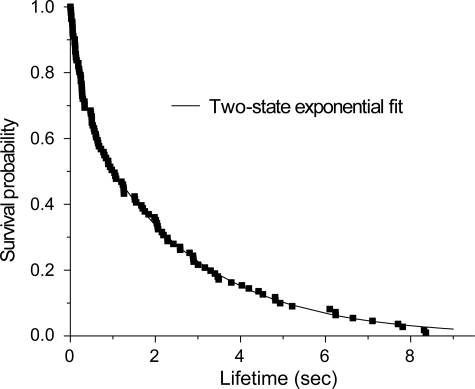

After initial contact, the force on the bond was stepped to a low force, e.g. 40 ± 1 pN at 1200 ± 180 pN/s, and then held until the bond failed. The persistence time of the bond under constant force is the lifetime. From the measured lifetimes, we then constructed the survival probability curve in Fig. 4. Importantly, the 40 pN holding force was sufficient to completely eliminate the low force peak, so that the lifetime data only reflect bonds that rupture at forces >40 pN.

FIGURE 4.

Survival probability versus lifetime of a homophilic N-CAD bond subject to a constant, applied force of 40 ± 1. 2 pN. The data were fit to a superposition of two exponential functions, indicating that two substates contribute to the peak at >40 pN.

Fitting to Equation 4 (or a superposition of exponentials) showed that the survival probability curve is best described by the sum of two exponentials. The high force peak therefore includes two bound states, as reported for C-CAD and mouse E-CAD (29, 33). An F test (44, 45) confirmed that a two-exponential function best describes the data. The parameters characterizing these sub-states were determined from plots of the dissociation rate as a function of the holding force (supplemental Fig. S1). In contrast to the more sensitive BFP measurements, lifetime measurements of the peak at lower rupture forces were not possible, because of the difficulty of reproducibly stepping the force to <30 pN. However, based on the similar analysis of the high force peaks measured with the BFP and AFM, we assume that the low force peak similarly includes two sub-states.

In prior measurements of E-CAD and C-CAD, the same principal adhesive states determine the peak maxima at each loading rate. We demonstrated this by fitting the data to the cumulative distribution function over a range of loading rates (not shown). These fits showed that the same prominent bound state dominates the second peak in the histograms at all loading rates. The same sub-state also presumably dominates the low force peak at all loading rates. Subsequent analyses therefore focused on the maxima of the two major peaks, and their variation with loading rate, cadherin identity, and the type (homophilic versus heterophilic) of cadherin interaction.

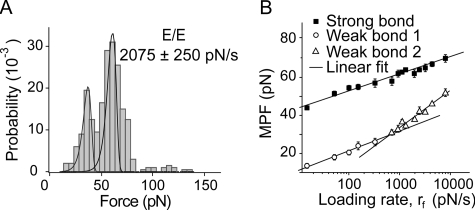

The force spectra of canine E-CAD differed slightly from those of N-CAD and C-CAD (Fig. 5). Fig. 5A shows the force histogram measured at 2075 ± 250 pN/s, and Fig. 5B shows the plot of the MPF versus log(rf) for the two peaks. In contrast to N-CAD, the MPF for the lower force peak did not increase linearly with log(rf). Panorchan et al. (48) reported similar behavior in AFM measurements between recombinant canine E-CAD ectodomains and cells expressing wild type E-CAD. This could be due to two energy barriers in the unbinding trajectory (42, 46). An alternative analysis predicts this force signature for bonds confined by a single barrier and a cup-like potential (47). Alternatively, this could be due to a rate-dependent shift in the populations of two states contributing to the low force peak.

FIGURE 5.

Adhesion measurements between E-CAD ectodomains. A, histogram of the rupture forces measured at the steady loading rate of 2075 ± 250 pN/s. B, plot of the most probable force (MPF) versus log(rf) and linear fits to the data (solid lines). The best fit parameters from the force spectra are fβ = 4.0 ± 0.2 pN and koff = 4 ± 1 × 10-5 s-1 for the strong state. The fits to two branches of low force peak, assuming two energy barriers in the unbinding trajectory, give fβ = 4.5 ± 0.4 pN and koff = 0.2 ± 0.1s-1 for the shallow branch, and fβ = 8 ± 0.7 pN, koff = 2 ± 1 s-1 for the steepest branch. The best fit parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Assuming two barriers in the unbinding trajectory (42, 46), one obtains linear fits to the two branches shown in Fig. 5B. The two branches in the force spectrum for the lower force peak appear to be similar. However, a Student's t test shows that the difference in the two slopes is statistically significant (p < 0.01). The best fit bond parameters are given in Table 1.

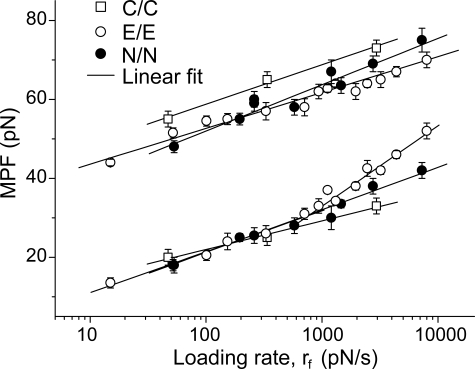

Fig. 6 summarizes the force spectra of the homophilic bonds measured with all three classical cadherin ectodomains. The fitted parameters fβ and koff are summarized in Table 1. All three interactions exhibited two principal peaks over the loading rates used. Importantly, the homophilic bonds of all three cadherin subtypes exhibit very similar tensile strengths and force spectra. The only major difference appears to be the nonlinearity of the force spectrum of the low force E-CAD peak. Differences in the slopes also affect the determined dissociation rates.

FIGURE 6.

Summary of force spectra for the homophilic cadherin interactions and linear fits to the data. All three homophilic interactions exhibited two principal peaks over the loading rates examined. The best fit parameters (fβ and koff) for each of the cadherin bonds are summarized in Table 1.

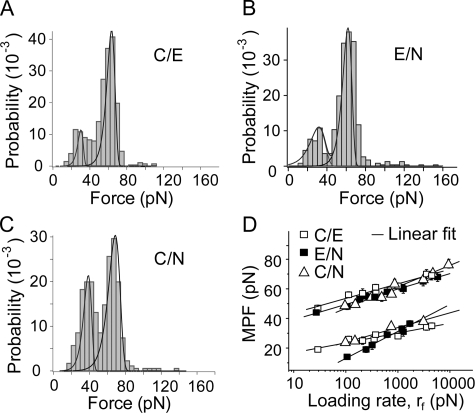

Heterophilic and Homophilic Cadherin Bonds Are Similar—Heterophilic binding between the three different cadherins was measured as described above. Fig. 7, A–C, shows representative histograms force obtained for the three heterophilic cadherin interactions as follows: namely E-CAD/N-CAD, C-CAD/E-CAD, and C-CAD/N-CAD. Similar to the homophilic bonds, heterophilic interactions also exhibit two principal peaks. In each case, the cadherins exhibit distinct weak bonds rupturing at <40 pN and strong bonds that rupture between 45 and 75pN, depending on the loading rate. The solid lines in the figures are the estimated force distributions.

FIGURE 7.

Summary of heterophilic cadherin interactions. Histograms of the rupture forces measured between C-CAD and N-CAD (1080 ± 120 pN/s) (A), E-CAD and N-CAD (1270 ± 150 pN/s) (B), and N-CAD and C-CAD (3070 ± 500 pN/s) (C). D, summary of force spectra of the strong and weak heterophilic bonds together with linear fits to the curves. The best fit parameters for each of the bound states are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 7D summarizes the force spectra for all heterophilic interactions measured between these different cadherins. In contrast to the force spectrum of the homophilic E-CAD bonds, the MPFs for heterophilic bonds are all linear functions of log(rf). The corresponding bond parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Time Evolution of the Population Distribution—There are two principal differences between the cadherin rupture forces reported here and the rupture forces between soluble, recombinant ectodomains and live cells reported previously (48). First, the latter study suggested that canine E-CAD only forms a single bound state, in contrast to these and previous measurements (29, 33). Second, Panorchan et al. (48) reported no heterophilic binding between canine E-CAD and human N-CAD, whereas the soluble, recombinant ectodomains of all three cadherin subtypes investigated here cross-react.

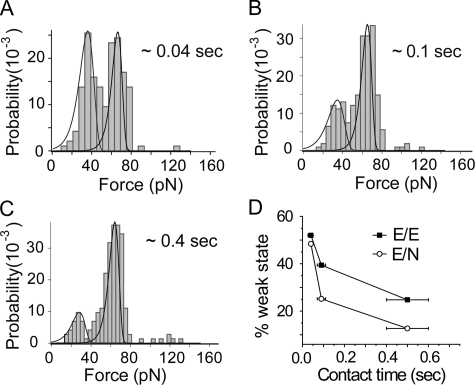

To test whether these apparent differences are related to cadherin binding kinetics, we investigated the relative population distributions as a function of the tip-surface contact time. Perret et al. (29) showed that the relative population of weak versus strong bonds changed with the contact time. The AFM measurements with cells used fast tip cycling rates to reduce nonspecific binding (48). Under these conditions, the resulting tip-surface contact time could be too short to populate the stronger bound state.

To test this, we varied the tip-surface contact time from 0.04 to 0.4 s and quantified the relative population of weak bonds. Fig. 8, A–C, shows the time-dependent shifts in the amplitudes of the two peaks. To compare with the earlier study (48), we similarly focused on both homophilic E-CAD and heterophilic E-CAD/N-CAD bonds. The relative population of weak bonds decreases with time, with a corresponding increase in the relative population of stronger bonds. This behavior is similar for both homophilic E-CAD and heterophilic E-CAD/N-CAD bonds. Fig. 8D summarizes the quantitative changes in the percentage of weak bonds with time, for both E-CAD/E-CAD and E-CAD/N-CAD bonds. These results indicate that faster cycling rates could bias the measurements toward the weaker bonds with faster kinetics.

FIGURE 8.

Shift in the relative populations of weak and strong bonds with the tip-surface contact time. A–C, force histograms and fitted distributions change with the contact time for homophilic E-CAD bonds. Distributions were plotted with fβ = 4.6 pN and koff = 4 × 10-4 s-1 for the strong bond, and fβ = 8 pN and koff = 2.5 s-1 for the weak bond. The rupture forces of E-CAD/N-CAD and E-CAD/E-CAD bonds were measured at rf = 1250 ± 165 pN/s. D, percentage of weak bonds versus tip-surface contact time for homophilic E-CAD bonds and heterophilic E-CAD/N-CAD bonds. As the contact time increases, the relative percentage of weak bonds decreases.

Cell Segregation Results—Cadherin binding specificity is thought to be a primary factor driving cell sorting. The findings described above show that the cadherins all cross-adhere. Comparisons of the intrinsic bond parameters against cell-sorting outcomes were used to identify which, if any, cadherin bond parameters correlate with cell segregation.

Both short term cell aggregation cultures and in long term hanging drop cultures, determined the cadherin-dependent sorting behavior of CHO cells. In both assays, cells had similar cadherin surface expression levels, as determined by flow cytometry and by immunoblotting of cell lysates (supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Fluorescence-activated cell-sorting data, which were used to select clones with similar cadherin expression, were compared with immunoblots for cadherin and for β-catenin. In CHO cells, β-catenin is expressed proportionally with cadherin.3

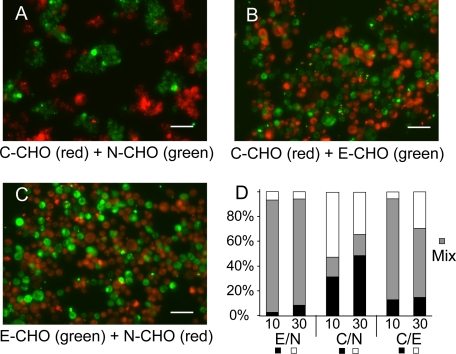

Fig. 9, A–C, shows the fluorescence microscopy images of the cell aggregates obtained in the short term cell aggregation culture after shaking the cell suspensions for 1 h at 160 rpm. We compared cell segregation behavior at two cadherin expression levels, namely ∼10 and ∼30/μm2. In each measurement, the expression levels of the different cadherins differed by less than 20%. Fig. 9D gives the percentages of mixed versus segregated aggregates. In this assay, E-CHO and N-CHO cells intermix, as do the E-CHO and C-CHO. E-CHO/C-CHO cell mixtures with the higher protein expression levels (∼30/μm2) formed slightly more homoaggregates. By contrast, C-CHO and N-CHO segregated, regardless of the cadherin expression level.

FIGURE 9.

Results of short term aggregation cultures with mixtures of C-CHO, N-CHO, and E-CHO. A, C-CHO versus N-CHO; B, C-CHO with E-CHO; and C, E-CHO with N-CHO. D, bar graphs show the relative percentages of homo- and heteroaggregates measured after 1 h. The specific cadherin pairs are indicated below, and the cadherin densities are also indicated below each bar (10 and 30/μm2). Black and white bars indicate the percentages of homoaggregates, and the gray bars indicate the percentages of mixed or heteroaggregates. The black bars indicate the first of the pair, and white bars indicate the second of the pair, e.g. E(black)/N(white).

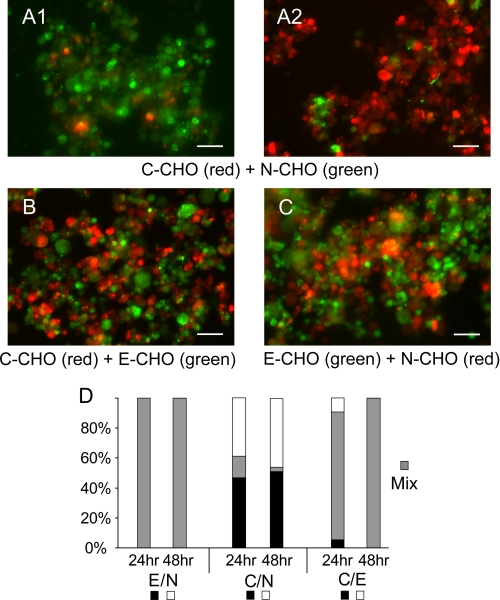

The results obtained with the long term aggregation cultures were similar. Fig. 10, A–C, shows the aggregates formed after 48 h in culture. Fig. 10D gives the percentage of homo- and heteroaggregates after 24 and 48 h in culture. Despite differences in the assay conditions and the factors contributing to cell movements and bond disruption, the segregation profiles in the different assays are similar.

FIGURE 10.

Results of long term aggregation cultures (hanging drop) with N-CHO, E-CHO, and C-CHO. A, C-CAD and N-CAD; B, C-CHO and E-CHO; and C, E-CHO and N-CHO after 48 h. D, bar graphs showing the percentages of homo- and heteroaggregates after 24 and 48 h. The cadherin pairs are indicated below. The cadherin densities were all ∼10/μm2. Black and white bars indicate the percentages of homoaggregates, and the gray bars indicate the percentages of mixed aggregates. The black bars indicate the first of the pair, and white bars indicate the second of the pair, e.g. E(black)/N(white).

DISCUSSION

Cadherin Ectodomains Cross-react—At the single molecule level, classical cadherins form both homophilic and heterophilic bonds. This demonstrated cross-reactivity (Fig. 7) agrees with prior findings. Surface force measurements also showed that these same cadherins cross-react, and the adhesion energies were not generally higher for homophilic bonds (20). In flow assays, cells expressing Xenopus C-CAD, human E-CAD, or human N-CAD bound equally well to substrata coated with recombinant human E-CAD ectodomains (19). In long term aggregation cultures, cells expressing different cadherin subtypes also intermix (49). Taken together, these results, which are based on measurements with different cadherins and with different experimental approaches, show that classical cadherins cross-react. Furthermore, homophilic bonds are not generally kinetically or thermodynamically favored over heterophilic interactions.

Cadherin Exhibits Multiple Bound States That Dynamically Interconvert with Time—The two peaks in the force histograms support the multistate cadherin-binding mechanism identified with the biomembrane force probe (BFP) (29, 33), surface force apparatus (20, 28, 32, 50), and more recent adhesion measurements between single cells (31). Here we confirmed that the high force peak includes two states, as demonstrated previously with the BFP (29, 33). By analogy with the prior studies, the low force peak also likely includes two adhesive states. However, for the sake of comparisons between different cadherins, this study focused on differences in the most prominent states, which determine the two maxima in the histograms.

AFM measurements lack spatial information, so it is not possible to directly map the weak and strong bonds to domains, as in SFA experiments (28). It is also not possible to distinguish between cis and trans bonds. However, three independent measurements mapped the fast, initial weak binding to EC12 (28, 29, 31) and demonstrated that the full ectodomain, is required for the subsequent transition to a second binding state (31). The dissociation rate of the weak bond (low force peak) compares quantitatively with fast, weak E-CAD bond (31). The dissociation rates determined for the high force peaks in this study also compare quantitatively to one of the strong bonds measured with mouse E-CAD and with Xenopus C-CAD (29, 33). Based on the qualitative and quantitative parallels with prior studies, we attribute the weak (low force) bond to EC12 and the strong (high force) bond to other EC domains in the full ectodomain (28).

Previous findings demonstrated that cadherins rapidly associate via EC1 domains, and then transition to a second state, which requires EC3 (29, 33). In this study, the relative population of strong bonds increases with contact time, as reported for mouse E-CAD (29). There are also clear parallels between the transition documented here and the two-stage binding kinetics reported for cadherin-mediated cell adhesion (31). Based on the similarities in the kinetics of single bond and cell adhesion measurements, we speculate that these time-dependent transitions are because of the identical or closely coupled processes.

Correlating Cadherin Bond Parameters with Cell Segregation Outcomes—The tensile strengths and the force spectra of both homophilic and heterophilic cadherin bonds are qualitatively similar (Figs. 6 and 7). However, quantitative comparisons of the parameters determined from the plots are more informative. The dissociation rates of the strong, heterophilic bonds are faster than those of the corresponding homophilic bonds. The faster rates correlated with larger thermal forces, but differences in fβ are modest. There are, however, no similar trends in the dissociation rates or thermal force scales fβ of the weak EC1-dependent bonds. Additionally, the force spectrum for the weak E-CAD bond is not linear with log(rf) over the entire range of loading rates. None of these features, however, correlate with cell-sorting behavior.

We compared the biophysical properties of cadherin bonds with outcomes from two different cell-sorting assays. In both short term and long term cell aggregation cultures, only Xenopus C- and chicken N-CAD-expressing cells sorted out. At the same time, E- and C-CHO as well as E- and N-CHO formed mixed aggregates. Prakasam et al. (20) compared the adhesion energies measured with these same cadherins with cell sorting outcomes reported previously (19). In the latter comparison, the species origins of the E- and N-CADs studied with the SFA differed from those in the cell-sorting studies. By contrast, this study used the same three classical cadherins in both the biophysical measurements and sorting assays. The cadherin expression levels on the CHO cells were also controlled.

Table 2 summarizes qualitative trends in the adhesion energies (20) and dissociation rates (Table 1). One can draw a few conclusions from these findings. First, cell sorting in vitro is not determined by either weaker homophilic versus heterophilic adhesion energies or by faster heterophilic bond dissociation rates. Interestingly, the dissociation rate of the strong, heterophilic C-CAD/N-CAD bond was at least 1 order of magnitude faster than any of other strong cadherin bonds, whereas only C-CHO/N-CHO sorted out. However, the bond properties of other two heterophilic cadherin pairs did not correlate with cell-sorting results. There was similarly no correlation between cell-sorting outcomes and the relative dissociation kinetics of the weak EC1 bonds.

TABLE 2.

Relative dissociation rates and adhesion energies for homophilic (Hom) versus heterophilic (Het) cadherin bonds Cases in which the heterophilic bond parameter is intermediate between the corresponding homophilic interactions are designated “Intermed.”

|

Cell

sortinga

|

Strong bond

|

Weak bond

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation ratesa | Adhesion energiesb | Dissociation ratesa | Adhesion energiesb | ||

| C-CAD/E-CAD | Intermix | Het ≥ Hom | Het < Hom | Het < Hom | Het ≤ Hom |

| p = 0.5c | p = 0.35 | ||||

| E-CAD/N-CAD | Intermix | Intermed. | Het > Hom | Het > Hom | Intermed. |

| C-CAD/N-CAD | Sort | Het > Hom | Intermed. | Intermed. | Intermed. |

| p = 0.04 | |||||

Equilibrium models of cell sorting based on differences in adhesion and/or Gibbs free energies of the protein bonds (15, 16) predict demixing when the interfacial tension between dissimilar liquids/cells is intermediate between the surface tensions of the pure (homophilic) materials, that is when Wab < ½(Waa + Wbb), where W is the adhesion energy. Based on this argument, the adhesion energies for the strongest cadherin bonds measured with the SFA (20) predict that only E-CHO and C-CHO would sort out. Alternatively, based on the adhesion energies of the weak cadherin bonds, only E-CHO and C-CHO should segregate. This prediction differs from the experimental results.

Previous studies correlated cell sorting with indirectly determined intercellular adhesion energies (intercellular tension) (18). However, in cell aggregates, several factors could augment or mask subtle differences in the biophysical properties of cadherin ectodomains. In addition to cell surface densities, cortical tension may influence the overall intercellular tension (17). Recombinant ectodomains could differ from cadherin at the cell surface. This is not likely, however. Within the first 40 s of cell-cell contact, recombinant and wild type cadherins behave similarly (31). Similarities between the canine E-CAD bonds reported here and those measured between the recombinant ectodomain and cell surface E-CAD also argue against this possibility (48).

One might question whether the lack of correlation between cadherin bond properties and cell sorting depends on the species origin of the cadherin. The source of the cadherin is relevant, but only in the context of detailed structure (sequence) differences and their impact on bond chemistry and consequent biophysical properties. This study addressed whether the biophysical properties of the bonds, which are related to structure, dictate cell sorting. The conclusion is based on thermodynamic and kinetic correlations. Because these parameters are only indirectly related to the species of origin, the absence of an obvious correlation between sorting and either bond energy or kinetics is also independent of the cadherin source.

These findings instead suggest that other factors have a greater impact on the intercellular interactions underlying cell sorting. Segregation models assume uniform cadherin distributions and uniform cadherin properties over the cell population in the aggregate. Cadherin oligomerization could alter activity (51). Outside-in/inside-out signaling may generate differences in cadherin-mediated adhesion (2, 5, 35). Differences in intracellular signaling by different cadherin subtypes could further influence cell adhesion and motility. Addressing these other possible contributions is beyond the scope of this work. Importantly, however, the ability to quantify cadherin bond parameters at the protein level and to compare them with sorting outcomes enabled us to rigorously evaluate the hypothesis that differential binding between cadherin ectodomains is sufficient to drive cell sorting.

In summary, these AFM measurements demonstrate that cadherin subtypes cross-react. They also extend prior surface force measurements of canine E-CAD, chicken N-CAD, and Xenopus C-CAD by quantifying the single bond strengths, thermal force scales (fβ), and dissociation rates. The mechanical and kinetic properties of the heterophilic bonds do not differ substantially from homophilic bonds. This supports the accumulating evidence that cadherins exhibit only modest binding specificity. Further comparison of these results with two different cell-sorting assays, which are thought to mimic in vivo cell sorting, shows that biophysical differences between cadherins do not account for segregation outcomes. These findings suggest that cell sorting in vivo and in vitro is likely governed by several factors, which may include but are not determined solely by subtle variations in cadherin bonds.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 GM51338. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: N-CAD, neural cadherin; E-CAD, epithelial cadherin; NHS, N-hydroxysuccinimide; AFM, atomic force microscope; BSA, bovine serum albumin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; MPF, most probable force; EC, extracellular; BFP, biomembrane force probe; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; pN, piconewton.

C. M. Niessen, personal communication.

References

- 1.Takeichi, M. (1988) Development (Camb.) 102 639-655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gumbiner, B. M. (1996) Cell 84 345-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeichi, M. (1991) Science 251 14511455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeichi, M. (1995) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7 619-627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gumbiner, B. M. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 622-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronner-Fraser, M., Wolf, J. J., and Murray, B. A. (1992) Dev. Biol. 153 291-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detrick, R. J., Dickey, D., and Kintner, C. R. (1990) Neuron 4 493-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsunaga, M., Hatta, K., and Takeichi, M. (1988) Neuron 1 289-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeichi, M. (1990) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59 237-252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nose, A., Nagafuchi, A., and Takeichi, M. (1988) Cell 54 993-1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyatani, S., Shimamura, K., Hatta, M., Nagafuchi, A., Nose, A., Matsunaga, M., Hatta, K., and Takeichi, M. (1989) Science 245 631-635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inuzuka, H., Miyatani, S., and Takeichi, M. (1991) Neuron 7 69-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth, S. A., and Weston, J. A. (1967) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 58 974-980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nose, A., Tsuji, K., and Takeichi, M. (1990) Cell 61 147-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinberg, M. S. (1963) Science 141 401-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, C. P., Posy, S., Ben-Shaul, A., Shapiro, L., and Honig, B. H. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 8531-8536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieg, M., Arboleda-Estudillo, Y., Puech, P. H., Kafer, J., Graner, F., Muller, D. J., and Heisenberg, C. P. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10 375-377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foty, R. A., and Steinberg, M. S. (2005) Dev. Biol. 278 255-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niessen, C. M., and Gumbiner, B. M. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 156 389-399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prakasam, A. K., Maruthamuthu, V., and Leckband, D. E. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 15434-15439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boggon, T. J., Murray, J., Chappuis-Flament, S., Wong, E., Gumbiner, B. M., and Shapiro, L. (2002) Science 296 1308-1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yap, A. S., Brieher, W. M., and Gumbiner, B. M. (1997) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13 119-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Overduin, M., Harvey, T. S., Bagby, S., Tong, K. I., Yau, P., Takeichi, M., and Ikura, M. (1995) Science 267 386-389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro, L., Fannon, A. M., Kwong, P. D., Thompson, A., Lehmann, M. S., Grubel, G., Legrand, J.-F., Als-Nielsen, J., Colman, D. R., and Hendrickson, W. A. (1995) Nature 374 327-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura, K., Shan, W.-S., Hendrickson, W. A., Colman, D. R., and Shapiro, L. (1998) Neuron 20 1153-1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pertz, O., Bozic, D., Koch, A. W., Fauser, C., Brancaccio, A., and Engel, J. (1999) EMBO J. 18 1738-1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chappuis-Flament, S., Wong, E., Hicks, L. D., Kay, C. M., and Gumbiner, B. M. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154 231-243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu, B., Chappuis-Flament, S., Wong, E., Jensen, I., Gumbiner, B. M., and Leckband, D. E. (2003) Biophys. J. 84 4033-4042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perret, E., Leung, A., Feracci, H., and Evans, E. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 16472-16477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayas, M. V., Kearney, A., Avramovic, A., van der Merwe, P. A., and Leckband, D. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 5589-5596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chien, Y.-H., Jiang, N., Li, F., Zhang, F., Zhu, C., and Leckband, D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 1848-1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sivasankar, S., Gumbiner, B., and Leckband, D. (2001) Biophys. J. 80 1758-1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayas, M. V., Leung, A., Evans, E., and Leckband, D. (2006) Biophys. J. 90 1385-1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg, M. S., and Takeichi, M. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 206-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leckband, D., and Prakasam, A. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 8 259-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeichi, M., and Nakagawa, S. (2001) Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 9, Unit 9.3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Zhang, F., Marcus, W. D., Goyal, N. H., Selvaraj, P., Springer, T. A., and Zhu, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42207-42218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wieland, J. A., Gewirth, A. A., and Leckband, D. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 41037-41046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hutter, J. L., and Bechhoefer, J. (1993) Rev. Sci. Instrum. 64 1868-1873 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall, B. T., Long, M., Piper, J. W., Yago, T., McEver, R. P., and Zhu, C. (2003) Nature 423 190-193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bell, G. I. (1978) Science 200 618-627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans, E., and Ritchie, K. (1997) Biophys. J. 72 1541-1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott, D. W. (1992) Multivariate Density Estimation: Theory, Practice, and Visualization, Wiley Interscience, New York

- 44.Beck, J. V. (1977) Parameter Estimation in Engineering and Science, (Arnold, K., ed) John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York

- 45.Hukkanen, E. J., Wieland, J. A., Gewirth, A., Leckband, D. E., and Braatz, R. D. (2005) Biophys. J. 89 3434-3445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merkel, R., Nassoy, P., Leung, A., Ritchie, K., and Evans, E. (1999) Nature 397 50-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hummer, G., and Szabo, A. (2003) Biophys. J. 85 5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Panorchan, P., Thompson, M. S., Davis, K. J., Tseng, Y., Konstantopoulos, K., and Wirtz, D. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119 66-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duguay, D., Foty, R. A., and Steinberg, M. S. (2003) Dev. Biol. 253 309-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sivasankar, S., Brieher, W., Lavrik, N., Gumbiner, B., and Leckband, D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 11820-11824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yap, A. S., Niessen, C. M., and Gumbiner, B. M. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141 779-789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.