Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the role of child religiosity in the development of maladaptation among maltreated children.

Methods

Data were collected on 188 maltreated and 196 nonmaltreated children from low-income families (ages 6–12 years). Children were assessed on religiosity and depressive symptoms, and were evaluated by camp counselors on internalizing symptomatology and externalizing symptomatology.

Results

Significant interactions indicated protective effects of religiosity. Child reports of the importance of faith were related to lower levels of internalizing symptomatology among maltreated girls (t = −2.81, p < .05). Child reports of attendance at religious services were associated with lower levels of externalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated boys (t = 1.94, p = .05).

Conclusion

These results suggest that child religiosity may largely contribute to stress coping process among maltreated and nonmaltreated children from low-income families. The results also indicate that the protective roles of religiosity varied by risk status and gender.

Practical Implications

The results indicate that a range of child religiosity behaviors and practices can be assessed in translational prevention research. It is recommended that healthcare professionals, psychologists, and social workers working with maltreated children and their families assess for salience of religiosity and may encourage them to consider the role religiosity plays in the development of prevention and intervention programs to alleviate distress and enhance stress coping.

Keywords: Child Maltreatment, Religiosity, Behavior Problems, Depression

Introduction

The deleterious effects of maltreatment on children’s behavior problems and psychopathology are well documented in the literature. The study of resilience in child maltreatment has searched for knowledge about the processes that account for positive adaptation of children who experience maltreatment in the context of disadvantage. The notion of personal religion or faith as a resilience factor appears in the early work of resilience research (e.g., Anthony & Cohler, 1987; Garmezy & Rutter, 1983; Werner & Smith, 1982). Empirical research has demonstrated that religious beliefs and church attendance form an important coping mechanism for negotiating life stresses (e.g., Hathaway & Pargament, 1990; Koenig, Siegler, & George, 1989). The existing literature on the role of religiosity in child development is in general consensus that religiosity promotes positive development and offers protection against risk behaviors (King & Furrow, 2004). Yet, no systematic study has been conducted with regard to the role of religiosity in the development of maladaptation among maltreated children. The current study, therefore, examines the role of child religiosity in seeking to understand resilient pathways among high-risk children with maltreatment experiences.

Child Maltreatment and Adjustment Problems

Research on the consequences of child maltreatment consistently highlights the long-term negative effects of child abuse and neglect on individual development. Victims of child maltreatment typically evidence difficulties in multiple domains of development including physical, psychological, cognitive, and behavioral development (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995). Children’s maladjustment associated with child maltreatment includes both internalizing symptomatology (Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001) and externalizing symptomatology (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 2001; Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997). Although numerous studies document that maltreated children manifest deficits in competent resolution of salient developmental tasks and develop consequent vulnerabilities for psychopathologic conditions, some maltreated children exhibit resilience, or competent outcomes, despite the severe adversity in their lives (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; McGloin & Widom, 2001). Less is known about resilient pathways. Knowledge about developmental processes contributing to resilience is critical for understanding pathways to adaptive and maladaptive development (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000).

Child Maltreatment and Religiosity

The association between maltreatment and religiosity is complex. Limited empirical work provides evidence for both greater and lesser religiosity among maltreated individuals. A theoretical approach to understanding this complexity has been offered by Granqvist and Dickie (2005) who proposed two different hypotheses based on the relationship between individual differences in attachment security and religiosity. The compensation hypothesis assumes that individuals who have experienced insecure childhood attachment relationships (as expected in maltreating families) are more likely to seek God for compensatory attachment relationships. According to this view, children with maltreatment experiences may regard God as a surrogate attachment figure. The correspondence hypothesis, on the other hand, suggests that individuals who have experienced secure, as opposed to insecure, childhood attachments have established the foundations on which a corresponding relationship with God could be built. It is expected that there is a strong correspondence between the ways in which children view their parents and the ways in which children view God. For example, nonmaltreated children, who are more likely to have secure attachment relationships with their primary attachment figures, may view God more loving and less punitive compared to maltreated children.

Although relatively few empirical studies have examined the association between child maltreatment and religiosity, most of the existing studies have supported the correspondence hypothesis. For example, victims of abuse are less likely to believe in God and to be involved in organized religion (e.g., Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1989; Hall, 1995; Kane, Cheston, & Greer, 1993). Our knowledge about child maltreatment and religiosity is limited because much of the previous research has focused exclusively on religiosity among adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Bierman’s (2005) study overcame such limitations of the prior research by examining the effects of physical and emotional abuse on religiosity in a U.S. probability sample of adults at midlife. The findings indicated that abuse perpetrated by fathers during childhood was related to decreases in religious involvement among adults.

In contrast, one study by Johnson and Eastburg (1992) supported both the compensation and correspondence hypotheses by showing that secure attachment characteristics and maltreatment experiences were associated with loving God images. More specifically, the authors studied children’s images of their parents and God and found that abused children perceived their parents less kind and more wrathful than do nonabused children. However, abused and nonabused children did not differ in their views of God as kind and close. Overall, the review of previous findings on the relation between child maltreatment and religiosity is rather equivocal and we know virtually nothing about religious behaviors and beliefs among children with diverse maltreatment experiences or about the roles they may play in the psychosocial sequelae of maltreatment. The current investigation aimed at examining child religiosity as a possible moderator of the effects of child maltreatment on behavior problems.

Religiosity and Adjustment Problems

A significant body of data demonstrates that religiosity has a positive influence on physical health and psychological well-being among older adults (e.g., Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001 for a review). In the last decade, interest has steadily grown in investigating the influences of religiosity on behavioral and emotional outcomes among adolescents. Empirical findings have documented modest influences of religiosity on negative outcomes such as delinquency, substance use, and depression as well as on positive outcomes such as physical and emotional health and education (e.g., Pearce, Little, & Perez, 2003; Regnerus, 2003 for review; Wallace & Forman, 1998;).

Past research has identified religiosity as having a protective effect against conduct problems, delinquency, and substance use (Johnson, Jang, Larson, & De Li, 2001; Marsiglia, Kulis, Nieri, & Parsai, 2005; Wallace, Brown, Bachman, & Laveist, 2003; Wills, Gibbons, Gerrard, Murry, & Brody, 2003). For example, in a longitudinal study of protective effects of religiousness among high-risk urban adolescents, higher levels of private religious practices and self-ranked religiousness protected against an increase in conduct problems over a 1-year period for adolescents exposed to violence (Pearce, Jones, Schwab-Stone, & Ruchkin, 2003). In addition, prior investigations involving adolescents have shown that those who frequently participated in religious activities reported that their religious beliefs were highly meaningful, and those who ranked themselves as highly religious had lower depression scores (Pearce, Little, et al., 2003; Wright, Frost, & Wisecarver, 1993).

While the correspondence and compensation hypotheses help us understand the association between affective aspects of religiosity and internalizing symptomatology, the association between religiosity and externalizing symptomatology may be better explained by social control theory (Hirschi, 1969). Social control theory characterizes religious communities as social networks of relational ties in which parents know their children's peer group and the parents of their children's peers. These types of relational networks facilitate oversight of child behavior as well as the internalization of adult norms regarding appropriate behaviors (Coleman, 1988). According to this view, it is hypothesized that public religiosity (e.g., attendance at religious services) may affect child behavior problems by acting as a form of social control.

The Role of Religiosity in the Link Between Maltreatment and Maladjustment

In a longitudinal study of resilience, Werner and Smith (1982) followed a group of high-risk children who were born into poor and troubled families into adulthood. For those resilient individuals who fared well academically and interpersonally by age 18, spirituality was identified among the most important protective factors associated with resilience. This finding suggests that religiosity may be a moderating factor (i.e., a resilience factor) in the link between negative life events and child outcomes. Indeed, research has revealed that religious beliefs and church attendance form an important coping mechanism for negotiating life stresses (Barbarin, 1999; Maltby & Day, 2003; McIntosh, Silver, & Wortman, 1993). For example, adolescents who lived in high-poverty areas were more likely to stay on track academically if they were high in church attendance compared to those who were low in church attendance (Regnerus & Elder, 2003). Another study suggests that religiosity may be a resilience factor that accounts for why some teen mothers and their children, who are at increased risk for negative developmental outcomes, fare better than others. In a sample of adolescent mothers and their children, mothers with greater religiosity (defined as church involvement and dependence on church officials and members) had higher educational attainment, higher self-esteem, and lower depression scores than mothers with lower religiosity (Carothers, Borkowski, Lefever, & Whitman, 2005).

A key contextual consideration is gender, given that the ways by which religiosity influences child psychopathology may well involve different processes for girls and boys. Although relatively little is known about differences in the mechanisms of risk and protection for girls and boys (Cicchetti & Sroufe, 2000), some evidence exists for differences in developmental pathways to internalizing symptomatology (Abela & Taylor, 2003; Mesman, Bongers, & Koot, 2001) and externalizing symptomatology (Kim, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1999) between boys and girls. Gender differences have also been reported in religiosity. Previous studies report that female adolescents are consistently more religious than male adolescents (Donahue & Benson, 1995; Smith, Denton, Faris, & Regnerus, 2002), and that the association between religiosity and health outcomes is stronger in women than in men (McCullough, Hoyt, Larson, Koenig, & Thoresen, 2000). A study on parenting style and children’s concepts of God showed that among 4- to 11-year old children parental discipline style had a significant effect on concepts of God for girls, but not for boys (Dickie et al., 1997). Overall, existing literature indicates different effects of religiosity on adjustment outcomes between boys and girls. This suggests that variations in adjustment outcomes within gender may not be explained by the same main and moderational effects of religiosity dimensions.

Present Study

No study to date has trained its focus on the associations between religiosity and socioemotional and behavioral outcomes among children with maltreatment experience. The unique contribution of this study to the field of child maltreatment and developmental psychopathology lies in its purpose to examine how child religiosity differentially predicts adjustment problems among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Based on the literature review, it was hypothesized that child religiosity would be related to lower levels of adjustment problems among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. The approach to examining the link between the relational risk factor (child maltreatment) and maladjustment outcomes stems from the risk and resilience literature (e.g., Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). Within the risk and resilience research framework, relational risk or protective factors can be seen as making additive or contingent contributions to adjustment. Accordingly, a main effect model postulates that religiosity decreases the probability of maladjustment in children, independent of the risk posed by maltreatment. Alternatively, a moderating effect model proposes that the contribution of religiosity to child maladjustment is contingent on the degree of life stress, such as maltreatment experiences. According to the stress-buffering perspective (Cohen & Wills, 1985), it was hypothesized that the negative association between religiosity and maladjustment would be stronger among maltreated children than nonmaltreated children.

Methods

Participants

Participants in the present study consisted of 188 maltreated children (111 boys and 77 girls) and 196 nonmaltreated children (88 boys and 108 girls) who attended a summer day camp research program in a Northeastern urban city. The summer camp program was designed to provide maltreated and nonmaltreated children from economically disadvantaged families with a naturalistic setting in which children’s behavior and peer interactions could be observed in an ecologically valid context.

Children were between the ages of 6 and 12 years. The sample consisted of children from diverse ethnic backgrounds: 63% African American, 17% European American, 17% Hispanic American, and 3% other ethnic groups. The maltreated group and the nonmaltreated group were comparable with respect to demographic features including child age (M = 8.5 years, SD = 1.1), ethnicity (85% minority ethnicity), annual household income (M = 24.02, SD = 13.25 in thousands of dollars), reliance on welfare (79% of families received Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or TANF), and parental marital status (61% of families were headed by single parents, typically mothers). There were more boys in the maltreated group compared to the nonmaltreated group, consistent with gender ratios in the maltreated population: 59% of the maltreated group were boys whereas 45% of the nonmaltreated group were boys, χ2 (1, N = 384) = 7.69, p<.05.

Procedure

Maltreated children had been identified through the Department of Social Services (DSS) as having experienced child maltreatment. Parental consent was obtained for examination of any DSS records. All existing DSS records were coded by raters utilizing a standardized classification system for child maltreatment developed by Barnett, Manly, and Cicchetti (1993). Nonmaltreated children were recruited from families receiving TANF through advertisements for a free children’s summer camp program and some monetary compensation for parents’ interviews, which were posted in local offices of the state public welfare agencies. The parents of these families were screened by phone and later interviewed to insure that they match the maltreating families on the demographic characteristics. Parental consent was obtained from these families to review the DSS records and Child Abuse Registry to confirm the absence of any documented maltreatment in these families. If any reports of child maltreatment or any ambiguous child maltreatment information were discovered for a family, the child was not included in the study.

Possibly eligible families were administered screening interviews by telephone or in their homes to inform them about the study procedures and camp program, and to obtain written informed consent and demographic information from the primary caregivers. In camp, children participated in a variety of recreational activities that were appropriate to their developmental level and interests in groups of six to eight same-age and same-sex peers. In addition, the children took part in a variety of research assessments. Every week, six groups of children participated in the camp and each camp group was led by three trained camp counselors. Half of the children in each of the groups were maltreated and the other half were nonmaltreated. Camp lasted for 5 days, 7 hours per day, thereby providing a total of 35 hours of interaction between children and counselors (see Cicchetti & Manly, 1990, for detailed descriptions of camp procedures). The counselors, who were unaware of the children’s maltreatment status and of the research hypotheses, completed a number of assessment instruments at the end of each week.

Measures

Child Maltreatment

The narrative reports of the maltreatment incidents from the DSS records were coded according to the Maltreatment Classification System (MCS, Barnett et al., 1993). The MCS provided operational definitions and specific criteria for rating the severity of multiple subtypes of maltreatment (See Barnett et al. 1993, for a detailed description of the nosological system used to code incidents for maltreatment). Severity of each subtype was rated along a 5-point scale (1 = mild to 5 = severe maltreatment). Additionally, the MCS coding involved measurement of onset and frequency of each subtype, perpetrator(s) within each subtype, and the developmental period(s) during which each subtype occurred.

Among maltreated children, 62% had been emotionally maltreated, 76% had been neglected, 27% had been physically abused, and 5% had been sexually abused. Consistent with the high co-occurrence of subtypes that are found in the literature (cf. Manly et al., 2001), 57% of the maltreated children in this sample experienced two or more forms of maltreatment. For 87% of the maltreated children, the child’s biological mother was named as a perpetrator for some form of maltreatment. About 40% of the maltreated children had fathers as perpetrators and about 40% had others as perpetrators (e.g., relatives). For each subtype, weighted kappa statistics were calculated to account for reliability. Interrater agreement was good, with kappas of 1.0 for sexual abuse, .94 for physical abuse, .78 for emotional maltreatment, and a range of .79–85 for physical neglect.

Child religiosity

Children were interviewed individually by a research assistant at camp using a survey measure of religiosity. The child religiosity measure consisted of three items that were adapted and revised from the National Survey of Children (NSC) (Gunnoe & Moore, 2002). The first item assessed frequency of attendance at religious services and activities [i.e., “How often do you go to church (for worship services and other church activities?)”]. Responses ranged from 1 (Two or three times of a week) to 5 (Never). The second item assessed the importance of faith to the participant (i.e., “How important is your faith in God or your beliefs in God to you?”) with responses ranging from 1 (Very important) to 5 (Not at all important). The third item assessed the frequency of prayer (i.e., “Rather than at mealtime, how often do you pray to God?”). Responses ranged from 1 (Several times a day) to 5 (Never). These items were reverse coded so that higher scores reflected greater religiosity. Three children answered ‘Never’ for attending church and missed the second item and two of these children missed the third item. For these cases, ‘Not at all important (=5)’ was given for the importance of faith and ‘Never (=1)’ was assigned for the frequency of prayer.

Children’s behavior problems – Counselor reports

Children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors were rated by camp counselors using the Teacher’s Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (TRF, Achenbach, 1991). The TRF is a widely used and well-validated instrument to assess a wide range of child behavioral disturbance. It consists of 118 items of behavior problems rated for frequency of occurrence including two broadband dimensions of child symptomatology – externalizing behavior problems (e.g., aggressive behaviors, delinquent behaviors) and internalizing behavior problems (e.g., withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxiety-depression). Two counselors’ scores for each child were averaged to obtain individual child scores for externalizing and internalizing symptomatology. Interrater reliabilities (intraclass correlations) ranged from .81 to .88 for externalizing symptomatology and from .62 to .71 for internalizing symptomatology.

Data analysis strategy

The present investigation used a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) and univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) covarying out child age to examine maltreatment effects regarding child religiosity and adjustment outcomes separately by gender. Given the high overlap in the multiple maltreatment subtypes, maltreated and nonmaltreated groups, rather than distinct subtypes, were compared. The main focus of the study, however, concerned testing of moderation effects of child religiosity in the link between child maltreatment and maladjustment outcomes using hierarchical regression models. To investigate gender differences in the moderating effects of religiosity, regression analyses were conducted separately for boys and girls. In Step 1, the main effects of maltreatment (dichotomous; nonmaltreated = 0 and maltreated = 1) and the three religiosity variables (continuous) on child adjustment were examined separately for internalizing symptomatology and externalizing symptomatology. In Step 2 the interactions between maltreatment and religiosity variables were added to test the moderational effects of religiosity.

Results

Maltreatment effects on religiosity and adjustment

The differences between maltreated and nonmaltreated groups were investigated by MANCOVAs controlling for child age separately by gender. Overall, the main effect of maltreatment was significant for child religiosity and behavioral problems among girls, Wilk’s Lambda F (5, 178) = 2.29, p < . 05. Individual F tests for each ANCOVA were examined to evaluate mean differences between maltreated and nonmaltreated groups. Table 1 shows means and standard deviations for study variables along with univariate F values separately for boys and girls according to maltreatment status. Regardless of gender, maltreated children exhibited significantly greater externalizing symptomatology than nonmaltreated children (p < .05). A marginal significance indicated that maltreated girls showed greater internalizing symptomatology compared to nonmaltreated girls (p = .09). In general, maltreated and nonmaltreated children did not differ in their reports of religiosity. One exception was that nonmaltreated girls tended to report that their faith was more important than did maltreated girls (p = .07).

Table 1.

Comparison of Maltreated and Nonmaltreated Groups on Study Variables Among Boys and Girls

| Variables | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmaltreated | Maltreated | Nonmaltreated | Maltreated | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | |

| Child Religiosity | ||||||

| Frequency of Attendance | 3.06(1.55) | 2.93(1.55) | .36 | 3.11(1.46) | 3.14(1.55) | .08 |

| Importance of Faith | 4.39(1.01) | 4.20(1.35) | .85 | 4.69(.65) | 4.47(.95) | 3.32+ |

| Frequency of Prayer | 3.63(1.20) | 3.47(1.26) | .67 | 3.65(1.24) | 3.43(1.25) | 1.08 |

| Child Outcomes | ||||||

| Internalizing (TRF) | 46.09(7.50) | 47.64(7.61) | 1.94 | 47.05(7.34) | 49.08(8.13) | 2.85+ |

| Externalizing (TRF) | 51.09(9.66) | 54.27(9.65) | 5.09* | 51.06(8.02) | 53.95(9.16) | 5.99* |

Note: TRF = Teacher’s Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist. Univariate df = 1, 196 for boys and Univariate df = 1, 182 for girls.

p < .10

p < .05.

Moderation effects of religiosity on the link between maltreatment and adjustment

Next, a series of hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted to examine the hypothesized moderating effects of children’s religiosity in the link between maltreatment and adjustment outcomes. More specifically, this regression model examined whether the effects of child religiosity on behavioral problems might differ depending on child maltreatment status. As shown in Table 2, separate models were tested for internalizing symptomatology and externalizing symptomatology by gender.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses to Predict Children’s Internalizing and Externalizing Symptomatology by Maltreatment and Religiosity

| Internalizing Symptomatology | Externalizing Symptomatology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls |

| Maltreatment | .10 | .12 | .16* | .16* |

| Frequency of Attendance | .03 | −.03 | −.11 | .10 |

| Importance of Faith | −.01 | −.06 | .02 | −.01 |

| Frequency of Prayer | −.08 | −.04 | −.02 | −.06 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Mal*FA | .17* | −.08 | .15(*) | .03 |

| Mal*IF | −.06 | −.22* | .14 | −.07 |

| Mal*FP | −.02 | .05 | −.11 | −.08 |

| F (the final model) | 1.15 | 2.01 (*) | 2.10* | 1.34 |

| df (Model/ Residual) | 7, 191 | 7, 177 | 7, 191 | 7, 177 |

| R2 (the final model) | .04 | .07 | .07 | .05 |

| Δ R2 For Step1-Step2 | .02 | .05* | .03 | .01 |

Note. FA= Frequency of Attendance; IF= Importance of Faith; FP = Frequency of Prayer. Standardized regression coefficients (betas) for the main effects are from the main effect model (Step 1) and standardized regression coefficients (betas) for the interaction effects are from the final model (Step 2).

p = .05

p < .05.

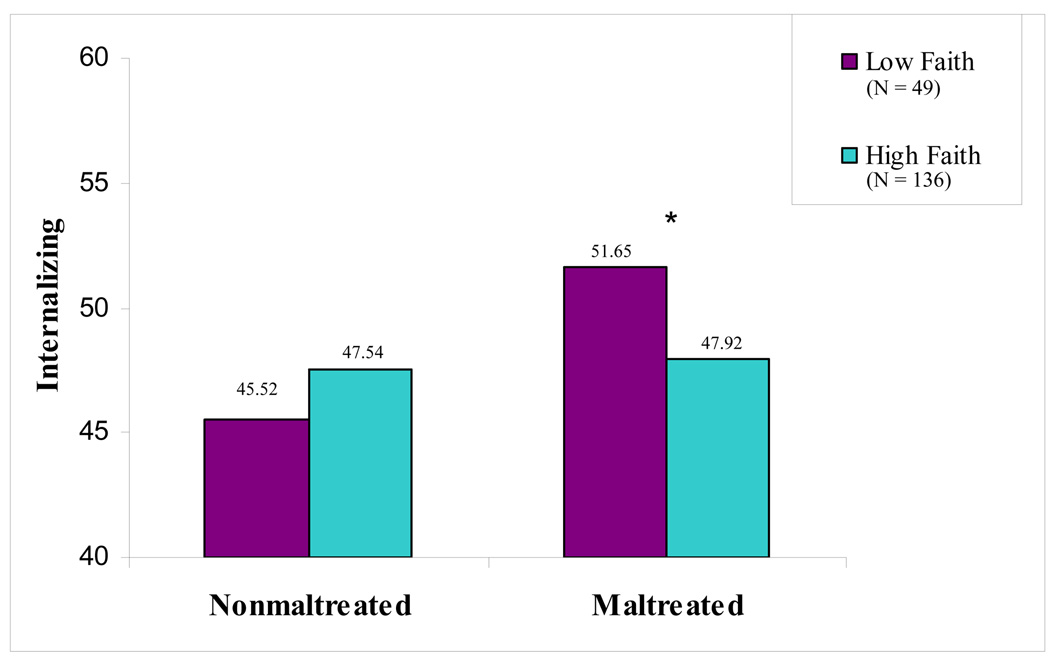

As for internalizing symptomatology among girls, there was a significant interaction effect between child maltreatment and the importance of faith reported by children. In order to describe significant interaction effects, the simple effects of child religiosity were examined separately for maltreated and nonmaltreated girls. The results revealed that the importance of faith was significantly related to internalizing symptomatology among maltreated girls (B = − 2.29, SE = .95, p < .05), but only marginally related to internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated girls (B = 1.86, SE = 1.08, p = .09). Figure 1 depicts the significant interaction effect between the importance of faith and maltreatment on girls’ internalizing symptomatology. To create Figure 1, the sample was split into two (low and high) groups on the importance of faith item. Maltreated girls with higher scores on the importance of faith (i.e., above the mean score for girls) showed significantly lower levels of internalizing symptomatology compared to maltreated girls who reported lower scores (i.e., below the mean score for girls). There was no significant difference between high and low importance of faith groups among nonmaltreated girls. With respect to boys’ internalizing symptomatology, the interaction between maltreatment and frequency of attendance was significant. However, because the overall significance of the regression model was not significant, simple effects were not tested.

Figure 1.

Means of Internalizing by Maltreatment and Importance of Faith among Girls. * p <.05

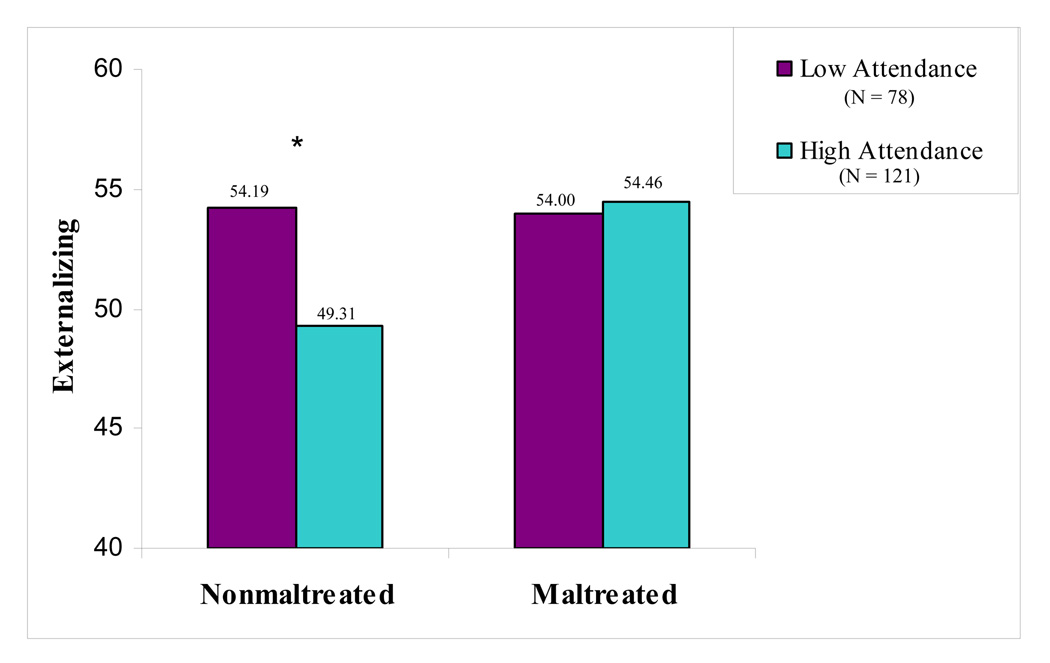

With respect to externalizing symptomatology among boys, there was a significant interaction between frequency of attendance and externalizing symptomatology (see Table 2). Regression analyses testing simple effects indicated that for nonmaltreated boys frequency of attendance was predictive of externalizing symptomatology (B = −1.67, SE = .65, p < .05). For maltreated boys, however, the frequency of attendance was not related to their externalizing symptomatology (B = .08, SE = .60, p = .90). To create Figure 2, the sample was split into two (high and low) groups on the attendance item. As can be seen in Figure 2, nonmaltreated boys with higher levels of attendance (i.e., above the mean score for boys) showed significantly lower levels of externalizing symptomatology compared to nonmaltreated boys with lower levels of attendance (i.e., below the mean score for boys). There was no significant difference between high and low attendance groups among maltreated boys. In addition, significant main effects of maltreatment indicated that maltreatment experiences were related to higher levels of externalizing symptomatology among girls even after controlling for child religiosity (B = 2.78, SE = 1.29, p < .05).

Figure 2.

Mean of Externalizing by Maltreatment and Church Attendance among Boys. * p <.05

Discussion

The current investigation was conducted to examine main and moderating effects of religiosity regarding internalizing and externalizing symptomatology among high-risk children with or without earlier maltreatment experiences. In general, the results provide support for the moderating effect model showing that the associations between child religiosity and adjustment outcomes differ depending on maltreatment status.

The buffering effects model (Cohen & Wills, 1985) suggests that the association between child religiosity and adjustment problems would be stronger at higher levels of psychosocial stress. Consistent with this view, the current data indicated that child religiosity (the value of faith) had a protective effect on internalizing symptomatology among children who experienced maltreatment, but such protective effects were gender specific. Among girls who had experienced abusive and/or neglectful parenting, those who viewed their faith as more important were less likely to exhibit internalizing symptomatology compared to those who regarded their faith less important. On the contrary, there was no association between the importance of faith and internalizing symptomatology among nonmaltreated girls. There was no strong evidence for moderating effects of child religiosity regarding boys’ internalizing symptomatology. As girls are at greater risk of experiencing internalizing symptomatology, religious coping styles may be more beneficial buffers against internalizing symptomatology for girls than for boys (e.g., Levin, Taylor, & Chatters, 1994).

More importantly, the finding supports the contention that the benefits of religiosity may be most evident among at-risk individuals who are confronted with a high degree of stress in their lives (Ellison, Boardman, Williams, & Jackson, 2001; Smith, McCullough, & Poll, 2003). Factors associated with greater religiosity, especially the private aspect of religiosity measured by importance of faith, seem to have the potential to reduce the effects of high stress levels associated with maltreatment experiences and improve psychological well-being among children, at least for girls. As King and Schafer (1992) suggested, religiosity may serve as a buffer to life’s adversities by providing personal meaning, broader perspectives on conflict, and inner resources in the face of stressful events. In the current sample, it appears that the personal aspect of religiosity (faith) provided maltreated girls with resources for inner strength in the face of life stress associated with maltreatment. It is speculated that children with greater faith may have more positive beliefs about oneself and one’s world, and thus are less likely to become hopeless or form a negative attribution style compared to those with lower levels of faith (e.g., Pearce, Little et al., 2003).

Interesting gender differences emerged suggesting gender-specific protective effects of religiosity. In contrast to the findings of the moderating effects of child religiosity regarding maltreated girls’ depressive symptoms, the findings for boys indicated significant protective effects of religiosity that were effective only in nonmaltreated children. More specifically, nonmaltreated boys who attended religious services more frequently showed lower levels of externalizing symptomatology compared to those who attended religious services less frequently. This finding may be explained by considering church attendance as constituting a form of social integration that has the consequence of reinforcing values conductive to upholding community values thus avoiding delinquent behaviors (e.g., Elder & Conger, 2000). As the social control theory (Hirschi, 1969) suggests, church attendance may function as a means of social control in that it can inhibit problematic antisocial behaviors and encourage prosocial behaviors among at-risk boys from low income families (Carothers et al., 2005; Cook, 2000; Pearce, Little et al., 2003). In addition, church may be an external support system outside of family that strengthens the resilience of children by providing positive role models and mentors, helping children develop self-regulatory abilities, and providing a supportive and stable community (Cook, 2000).

The non-significant effect of child religiosity on adjustment outcomes among maltreated boys suggests that child religiosity may not be a strong enough protective factor for attenuating the effects of maltreatment. Prior studies have illustrated that when the risk factors outweigh the benefits of the protective factors, children’s adjustment will deteriorate despite the presence of those protective factors (Zielinski & Bradshaw, 2006). It is possible that some other personality factors, such as social competence, are more influential than child religiosity in protecting maltreated boys who are facing relationship problems at home and among peers from developing externalizing symptomatology. For example, among boys having difficulty making and/or keeping friends, greater social competence was a significant predictor of lower externalizing symptomatology (Frankel & Myatt, 1994).

Contrary to some previous studies with adults (e.g., Finkelhor et al., 1989; Hall, 1995; Kane et al., 1993), there was little evidence in the present sample of a significant influence of child maltreatment on religiosity. Maltreated girls tended to be lower in importance of faith than nonmaltreated girls; however, there were no significant differences between the maltreated group and the nonmaltreated group regarding frequency of attendance and frequency of prayer among boys and girls or regarding importance of faith among boys. This finding is in line with previous findings by Johnson and Eastburg (1992) who reported that abused and nonabused children did not differ in their views of God as kind and loving. It can be speculated that, as the compensation hypothesis suggests, maltreated children’s religiosity may reflect stress-provoked distress regulation strategies, in which God is regarded as a substitute attachment-like figure (Granqvist & Dickie, 2005).

Consistent with the correspondence hypothesis, the current data demonstrated that nonmaltreated girls reported that their faith was more important than maltreated girls did. Prior research has shown that experiences of poor quality caregiving are related to the development of negative representational models of attachment figures (Cicchetti, 1991; Crittenden & Ainsworth, 1989). Child maltreatment reflects an extreme of caregiving dysfunction, and a greater percentage of insecure attachment relationships with primary caregivers has been documented among maltreated children (Crittenden, 1988; Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). Therefore, following the correspondence model, insecure attachment and poor quality parent-child relationships in maltreating families may explain why maltreated children are less likely to view their faith as important compared to nonmaltreated children. In a similar vein, Bierman (2005) reported that adults who experienced childhood maltreatment committed by fathers were lower in religious involvement. The author suggested that this finding indicated that the victims of paternal maltreatment may form a negative view of God, often identified as a paternal figure, and result in distancing themselves from religion.

Researchers have shown that frequency of personal prayer is a dominant religious measure in accounting for the link between religiosity and better mental health (i.e. lower depression and lower anxiety) among young adults (Maltby, Lewis, & Day, 1999). It is notable that, in the present study, frequency of personal prayers in middle childhood was not related to adjustment outcomes. This discrepancy in the findings underscores the need for studying developmental changes in the relations between dimensions of religiosity and emotional and behavioral adjustment.

From a measurement point of view, the findings from this study point out that it is important to involve diverse dimensions of religiosity measures. The moderating effects of religiosity found in this study suggest differential roles of diverse dimensions of religiosity in the development of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. This finding indicates that the different measures of religiosity used in the present study represent independent variance of religiosity. In addition, the result is largely consistent with the viewpoint that public measures of religiosity (frequency of attendance) and private measures of religiosity (importance of faith, frequency of prayer) represent separate religious dimensions (Brown, 1987).

Some limitations and recommended directions for future research need to be noted. First, in future research, more systematic and comprehensive theoretical and empirical examination is required regarding the multifaceted functions of religiosity in the development of children at risk. As Wallace and Williams (1997) suggested, the effects of religiosity may be largely indirect. Future research warrants identifying processes in which religiosity effects the outcomes from earlier experiences of child maltreatment by promoting positive developmental outcomes and reducing negative developmental outcomes. For example, research on the mechanisms by which religiosity exerts its effect on physical and mental health may include some personality factors such as perceived competence and self-concept, and social-relational factors such as social support and negative social interactions. Second, this study used cross-sectional data of religiosity and adjustment outcomes and thus causality in relations could not be verified in the regression models. This awaits further testing with longitudinal models. Future studies with prospective and longitudinal designs will make it possible to examine how religious protective processes change with development across life span. Finally, in future studies, it is recommended to consider contextual and individual factors that may determine the roles of religiosity as protective or risk factors (e.g. Crawford, Wright, & Masten, 2006). Unlike the findings of this study which showed religiosity as a protective factor, religiosity may be a risk factor for some individuals in some contexts. For example, in a study of religious/spiritual coping used by adult women with physical and/or sexual abuse histories and co-occurring with substance and mental health disorders, more frequent childhood abuse was related to higher levels of negative religious coping (Fallot & Heckman, 2005).

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that religiosity moderates the developmental effects of child maltreatment on adjustment outcomes, thereby accounting for some of the heterogeneity in the developmental outcomes associated with child maltreatment. This study has contributed to the expanding literature on protective mechanisms in child maltreatment by demonstrating that the protective roles of child religiosity varied by risk status and gender. The results point to the utility of future research focusing on the transactions of risk and protective processes leading to maladaptation. Such work is important for enhancing our understanding of adjustment problems among at-risk children and implementing effective preventive interventions.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01-MH068491). The author would like to thank Dante Cicchetti for his contributions to this study, Fred Rogosch, Jody Todd Manly, and Michael Lynch for their help with data collection and Carol Ann Dubovsky for her assistance in data management. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jungmeen Kim, Ph. D., Department of Psychology (MC 0436), Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061, U.S.A. Electronic mail may be sent to jungmeen@vt.edu.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abela JR, Taylor G. Specific vulnerability to depressive mood reactions in schoolchildren: The moderating role of self-esteem. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:408–418. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the teacher’s report form and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony EJ, Cohler BJ, editors. The invulnerable child. New York: Guilford; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin OA. Do parental coping, involvement, religiosity, and racial identity mediate children's psychological adjustment to sickle cell disease? Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25(3):391–426. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy: Advances in applied developmental psychology. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing; 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman A. The effects of childhood maltreatment on adult religiosity and spirituality: Rejecting God the father because of abusive fathers? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: Perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:913–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LB. The psychology of religious beliefs. London: Academic Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers SS, Borkowski JG, Lefever JB, Whitman TL. Religiosity and the socioemotional adjustment of adolescent mothers and their children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:263–275. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Fractures in the crystal: Developmental psychopathology and the emergence of self. Developmental Review. 1991;11:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Manly JT. A personal perspective on conducting research with maltreating families: Problems and solutions. In: Sigel I, Brody GH, editors. Methods of family research: Biographies of research projects: Volume 2. Clinical Populations. Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 87–133. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:797–815. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The impact of child maltreatment and psychopathology on neuroendocrine functioning. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:783–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Sroufe LA. The past as prologue to the future: The times, they've been a-changin'. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):255–264. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth S. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Cook KV. You have to have somebody watching your back, and if that's God, then that's mighty big: The church's role in the resilience of inner-city youth. Adolescence. 2000;35:717–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E, Wright MO, Masten AS. Resilience and spirituality in youth. In: Roehlkepartain E, King P, Wagner L, Benson P, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in children and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM. Relationships at risk. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, editors. Clinical maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 136–174. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden PM, Ainsworth M. Attachment and child abuse. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 432–463. [Google Scholar]

- Dickie JR, Eshleman AK, Merasco DM, Sherpard A, Vander Wilt M, Johnson M. Parent-child relationships and children’s images of God. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1997;36(1):25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. How the experience of early physical abuse leads children to become chronically aggressive. In: Cicchetti D, Toth S, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 8. The effects of trauma on the developmental process. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue MJ, Benson PL. Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues. 1995;51(2):145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Conger RD. Children of the land: Adversity and success in rural America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Boardman JD, Williams DR, Jackson JS. Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: Findings from the 1996 Detroit area study. Social Forces. 2001;80:215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, Heckman JP. Religious/spiritual coping among women trauma survivors with mental health and substance use disorders. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2005;32:215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF02287268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling GT, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse and its relationship to later sexual satisfaction, marital status, religion, and attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1989;4:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel F, Myatt R. Self-esteem, social competence and psychopathology in boys without friends. Personality and Individual Differences. 1994;20:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Rutter M. Stress, coping, and development in children. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist P, Dickie JR. Attachment and Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence. In: Roehlkepartain EC, King PE, Wagener LM, editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe ML, Moore KA. Predictors of religiosity among youth aged 17–22: A longitudinal study of the national survey of children. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:613–622. [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. Spiritual effects of childhood sexual abuse in adult Christian women. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1995;23:129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway WL, Pargament KI. Intrinsic religiousness, religious coping, and psychosocial competence: A covariance structure analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1990;29:423–441. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BW, Eastburg MC. God, parent, and self concepts in abused and nonabused children. Journal of Psychology and Christianity. 1992;11(3):235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BR, Jang SJ, Larson D, De Li S. Does adolescent religious commitment matter? A reexamination of the effects of religiosity on delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kane D, Cheston SE, Greer J. Perceptions of God by survivors of childhood sexual abuse: An exploratory study in an underresearched area. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1993;21:228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, Hetherington EM, Reiss D. Associations among family relationships, antisocial peers, and adolescents' externalizing behaviors: Gender and family type differences. Child Development. 1999;70(5):1209–1230. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Schafer WE. Religiosity and perceived stress: A community survey. Sociological Analysis. 1992;53:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- King PE, Furrow JL. Religion as a resource for positive youth development: Religion, social capital, and moral outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:703–713. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Siegler IC, George LK. Religious and nonreligious coping: Impact on adaptation in later life. Journal of Religion and Aging. 1989;5:73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:137–145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltby J, Day L. Religious orientation, religious coping and appraisals of stress: assessing primary appraisal factors in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:1209–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Maltby J, Lewis CA, Day L. Religious orientation and psychological well-being: The role of the frequency of personal prayer. British Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T, Parsai M. God forbid! Substance use among religious and nonreligious youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:585–598. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Hoyt WT, Larson DB, Koenig HG, Thoresen C. Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology. 2000;19:211–222. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGloin JM, Widom CS. Resilience among abused and neglected children grown up. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:1021–1038. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100414x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh DN, Silver RC, Wortman CB. Religion’s role in adjustment to a negative life event: Coping with the loss of a child. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:812–821. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.4.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Bongers IL, Koot HM. Preschool developmental pathways to preadolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:679–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Jones SM, Schwab-Stone ME, Ruchkin V. The protective effects of religiousness and parent involvement on the development of conduct problems among youth exposed to violence. Child Development. 2003;74:1682–1696. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Little TD, Perez JE. Religiousness and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:267–276. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD. Religion and positive adolescent outcomes: A review of research and theory. Review of Religious Research. 2003;44:394–413. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD, Elder GH., Jr. Staying on track in school: Religious influences in high- and low-risk settings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:633–649. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Denton ML, Faris R, Regnerus M. Mapping American adolescent religious participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(4):597–612. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:614–636. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D. Patterns of relatedness, depressive symptomatology, and perceived competence in maltreated children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(1):32–41. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Brown TN, Bachman JG, Laveist TA. The influence of race and religion on abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:843–848. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr., Forman TA. Religion's role in promoting health and reducing risk among American youth. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:721–741. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr., Williams DR. Religion and adolescent health-compromising behavior. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 444–468. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith RS. Vulnerable but invincible: A study of resilient children. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wills T, Gibbons F, Gerrard M, Murry V, Brody G. Family communication and religiosity related to substance use and sexual behavior in early adolescence: A test for pathways through self-control and prototype perceptions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:312–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright LS, Frost CJ, Wisecarver SJ. Church attendance, meaningfulness of religion, and depressive symptomatology among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1993;22:559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski DS, Bradshaw CP. Ecological influences on the sequelae of child maltreatment: A review of the literature. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:49–62. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]