Abstract

Protein palmitoylation is an essential post-translational lipid modification of proteins, and reversibly orchestrates a variety of cellular processes. Identification of palmitoylated proteins with their sites is the foundation for understanding molecular mechanisms and regulatory roles of palmitoylation. Contrasting to the labor-intensive and time-consuming experimental approaches, in silico prediction of palmitoylation sites has attracted much attention as a popular strategy. In this work, we updated our previous CSS-Palm into version 2.0. An updated clustering and scoring strategy (CSS) algorithm was employed with great improvement. The leave-one-out validation and 4-, 6-, 8- and 10-fold cross-validations were adopted to evaluate the prediction performance of CSS-Palm 2.0. Also, an additional new data set not included in training was used to test the robustness of CSS-Palm 2.0. By comparison, the performance of CSS-Palm was much better than previous tools. As an application, we performed a small-scale annotation of palmitoylated proteins in budding yeast. The online service and local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0 were freely available at: http://bioinformatics.lcd-ustc.org/css_palm.

Keywords: clustering and scoring strategy, CSS-Palm, palmitoylated proteins, palmitoylation

Introduction

As a special class of post-translational modifications, numerous proteins could be covalently modified by a variety of lipids, including myristate (C14), palmitate (C16), farnesyl (C15), geranylgeranyl (C20), glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) and so on (Casey, 1995; Nadolski and Linder, 2007; Resh, 2006a, 2006b). Although most of lipid modifications are irreversible, protein S-palmitoylation, also called as thioacylation or S-acylation, could reversibly attach 16-carbon saturated fatty acids to specific cysteine residues in protein substrates through thioester linkages (el-Husseini Ael and Bredt, 2002; Bijlmakers and Marsh, 2003; Dietrich and Ungermann, 2004; Smotrys and Linder, 2004; Resh, 2006a, 2006b; Roth et al., 2006; Greaves and Chamberlain, 2007; Linder and Deschenes, 2007; Nadolski and Linder, 2007; Wan et al., 2007). Palmitoylation will enhance surface hydrophobicity and membrane affinity of protein substrates, and plays important roles in modulating proteins’ trafficking (Draper et al., 2007; Linder and Deschenes, 2007), stability (Linder and Deschenes, 2007), sorting (Greaves and Chamberlain, 2007) and so on. Also, protein palmitoylation has been involved in numerous cellular processes, including signaling (Casey, 1995; Resh, 2006a, 2006b), apoptosis (Chakrabandhu et al., 2007), neuronal transmission (el-Husseini Ael and Bredt, 2002) and so on. Although many efforts have been made in this field, the molecular mechanisms underlying protein palmitoylation still remain to be inexplicit.

Identification of palmitoylation proteins with their sites is fundamental for elucidating the molecular mechanisms and dynamics of palmitoylation processes. However, experimental identification of palmitoylation substrates with their sites is quite difficult, because there is not a common motif for palmitoylation recognition (el-Husseini Ael and Bredt, 2002; Bijlmakers and Marsh, 2003; Dietrich and Ungermann, 2004; Smotrys and Linder, 2004; Roth et al. 2006; Linder and Deschenes, 2007; Nadolski and Linder, 2007). Conventionally, palmitoylation sites were usually mapped by mutagenesis of candidate cysteine residues. Without any guidance or pre-prediction, such a procedure is time-consuming and labor-intensive. Recently, with a high-throughput, tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS)-based proteomic methodology of MudPIT (multi-dimensional protein identification technology), a large-scale experiment was performed to identify ∼50 palmitoylated proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisae (Roth et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2007). However, the bona fide palmitoylation sites in most of these substrates still remained to be dissected. In this regard, computational prediction of palmitoylation sites in silico is urgent and greatly useful for further experimental verification.

In the field of computational lipid modifications, we and other researchers have taken great efforts to develop a variety of predictors (Eisenhaber et al., 1999; Eisenhaber et al., 2003; Bologna et al., 2004; Eisenhaber et al., 2004; Podell and Gribskov, 2004; Fankhauser and Maser, 2005; Maurer-Stroh and Eisenhaber, 2005; Xue et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2006). In 1999, Eisenhaber et al. constructed the first web server of ‘big-Pi predictor’ to predict potential GPI-anchor sites from protein sequences (Eisenhaber et al., 1999). The model combined several distinct features of GPI-anchor sites with 11 upstream and 10 downstream amino acid residues (Eisenhaber et al., 1999, 2003, 2004). And Fankhauser et al. employed an artificial neural network algorithm to develop the GPI-SOM, with a window length of 32 amino acid residues (Fankhauser and Maser, 2005). For prediction of N-myristoylation proteins, there were at least three web tools constructed, including NMT (Maurer-Stroh et al., 2002a, 2002b; Eisenhaber et al., 2003), Myristoylator (Bologna et al., 2004) and PlantsP (Podell and Gribskov, 2004). And for prediction of prenylated proteins, Eisenhaber et al. developed the Prenylation Prediction Suite (PrePS) (Maurer-Stroh and Eisenhaber, 2005). Previously, we constructed two online severs of CSS-Palm 1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0 to predict palmitoylation sites (Xue et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2006). The CSS-Palm 1.0 was implemented in Clustering and Scoring Strategy (CSS) algorithm (Zhou et al., 2006), whereas the NBA-Palm 1.0 was constructed with the Naïve Bayesian Algorithm (NBA) (Xue et al., 2006).

In this work, we updated our previous CSS-Palm 1.0 into version 2.0. We manually collected the experimentally verified palmitoylation sites from scientific literature. The non-redundant training data contained 263 palmitoylation sites from 109 distinct proteins. Then an improved version of CSS algorithm was deployed. The leave-one-out (Loo) validation and 4-, 6-, 8- and 10-fold cross-validations were calculated to evaluate the prediction performance and system robustness of CSS-Palm 2.0. Again, the prediction performance was also tested on an additional data set not included in the training data set, with 53 palmitoylation sites in 26 proteins. By comparison with our previous CSS-Palm1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0, the performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 was greatly improved. Finally, the online service and local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0 were implemented in JAVA 1.4.2 with high speed. The CSS-Palm 2.0 could predict potential palmitoylation sites for ∼1000 proteins (with an average length of ∼1000 amino acids) within 3 min. Taken together, we proposed that the CSS-Palm 2.0 will be a useful tool for experimentalists. The online service and local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0 were freely available at: http://bioinformatics.lcd-ustc.org/css_palm.

Materials and methods

Data preparation

We searched the scientific literature from PubMed with keywords of ‘palmitoylation’ or ‘palmitoylated’, and manually collected 340 experimentally verified palmitoylation sites in 145 proteins which were published before 8 October 2007. In this work, we arbitrarily took the 284 palmitoylation sites from 116 proteins published before November 2006 as the training data set. And the remaining 56 sites in 29 proteins were not included in training as an additional data set for performance evaluation. The protein sequences were retrieved from UniProt database (http://cn.expasy.org/uniprot).

As previously described (Xue et al., 2006), we regarded the cysteine (C) residues that undergo palmitoylation modification as positive data (+), while all other non- palmitoylated cysteine residues were taken as negative data (−). The positive data set (+) for training might contain several homologous sites from homologous proteins. If the training data were highly redundant with too many homologous sites, the prediction accuracy would be overestimated. To avoid the overestimation, we clustered the protein sequences with a threshold of 40% identity by CD-HIT (Li and Godzik, 2006). If two proteins were similar with ≥40% identity, we re-aligned the proteins with BL2SEQ, a program in the BLAST package (Altschul et al., 1997), and checked the results manually. If two palmitoylation sites from two homologous proteins were at the same position after sequence alignment, only one item was reserved while the other was discarded. Finally, the non-redundant data set for training contained 263 positive sites and 1150 negative sites from 109 substrates. And the non-redundant new data set contained 53 positive sites from 26 proteins. The training and new data sets are freely available upon request.

An upgraded algorithm of CSS

In CSS-Palm 1.0, the algorithm of CSS was employed (Zhou et al., 2006). And the experimentally verified palmitoylation sites were automatically clustered into three clusters by different thresholds of peptides similarity (Zhou et al., 2006). The clustering procedure was terminated, when the prediction performance was not significantly increased any more. Given a putative palmitoylation site for prediction, the CSS-Palm 1.0 will calculate a score between the sites with each cluster dependent on BLOSUM62 matrix, respectively. If the largest score was greater than the cut-off value, the putative site would be predicted as a positive hit.

In CSS-Palm 2.0, an updated version of CSS algorithm was used. First, we manually classified the known palmitoylation sites into three clusters, including Type I (sites follow a –CC– pattern, C is a cysteine residue), Type II (sites follow a –CXXC– pattern, C is a cysteine residue and X is a random residue) and Type III (other sites) group. Thus, the clustering procedure was based on experimental evidence rather than randomness. Then, we defined a potential palmitoylation peptide PPP(m, n) as a C residue flanked by m residues upstream and n residues downstream. By exhaustively testing, we chose PPP(25, 7), PPP(25, 16) and PPP(23, 15) for Type I, Type II and Type III palmitoylation sites, respectively. The training and prediction processes were separately performed on Type I, Type II and Type III palmitoylation sites, while the prediction results were integrated to calculate the final performance. Also, to improve the prediction performance, we developed a simple approach of matrix mutation (MaM). First, the BLOSUM62 was chosen as the initial matrix, and the Loo performance was calculated. Then, we fixed the specificity (Sp) as 85% to improve the sensitivity (Sn) by randomly picking out an element of the matrix for mutation. The procedure was terminated when the Sn value was not increased any more.

Performance evaluation

As previously described (Zhou et al., 2006), we used four measurements such as Sn, Sp, accuracy (Ac) and Mathew correlation coefficient (MCC) to evaluate the prediction performance of the CSS-Palm 2.0. The four measurements were defined as below:

and

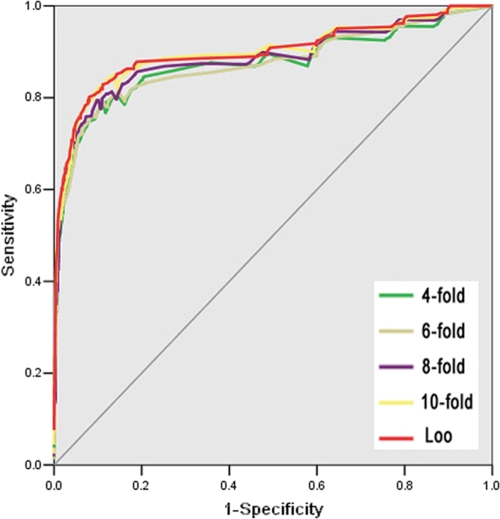

In this work, the Loo validation and 4-, 6-, 8- and 10-fold cross-validations were performed on the training data set (263 positive sites and 1150 negative sites). And the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn (Fig. 1). Also, the area under ROC (AROC) values were calculated as 0.8993 (Loo validation), 0.8732 (4-fold cross-validation, 4-fold), 0.8730 (6-fold cross-validation, 6-fold), 0.8864 (8-fold cross-validation, 8-fold) and 0.8982 (10-fold cross-validation, 10-fold). Thus, the results of 4-, 6-, 8- and 10-fold cross-validations were very similar with the Loo validation. In this regard, we took the Loo validation as an indicator of prediction performance of CSS-Palm 2.0. Also, we evaluated the robustness of CSS-Palm 2.0 with a new data set, including 53 verified palmitoylation sites in 26 substrates (published after Nov., 2006).

Fig. 1.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of leave-one-out (Loo) validation and 4-, 6-, 8- and 10-fold cross-validations (4-, 6-, 8- and 10-fold).

Implementation of the online service and local packages

The online service and local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0 were implemented in JAVA and freely available at http://bioinformatics.lcd-ustc.org/css_palm/prediction.php. For the online service, we tested the CSS-Palm 2.0 on a variety of internet browsers, including Internet Explorer 6.0, Netscape Browser 8.1.3 and Firefox 2 under Windows XP Operating System (OS), Mozilla Firefox 1.5 of Fedora Core 6 OS (Linux) and Safari 3.0 of Apple Mac OS X 10.4 (Tiger) and 10.5 (Leopard). For Windows and Linux systems, a latest version of Java Runtime Environment (JRE) package (JAVA 1.4.2 or later versions) of Sun Microsystems should be pre-installed for using the CSS-Palm 2.0 program. However, for Mac OS, the CSS-Palm 2.0 could be used directly without any additional packages. The online service of CSS-Palm 2.0 uses the local CPU for computation. Thus, the computing time is dependent on the users’ computers. In our laptop (IBM ThinkPad R51, 1.60 GHz, 768 MB), it only cost <3 min to predict palmitoylation sites for 1000 protein sequences (average length ∼1000 amino acids). For convenience, we also developed the local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0. The stand-alone software of CSS-Palm 2.0 supported three major OSs, including Windows, Linux and Mac.

Results

Development of the CSS-Palm 2.0 software

In this work, we used an updated version of CSS algorithm. The experimental results proposed that there is not a general consensus sequence for protein palmitoylation (el-Husseini Ael and Bredt, 2002; Bijlmakers and Marsh, 2003; Dietrich and Ungermann, 2004; Smotrys and Linder, 2004; Roth et al., 2006; Linder and Deschenes, 2007; Nadolski and Linder, 2007). However, there are still some sequence patterns for a large proportion of palmitoylation sites. For example, in budding yeast, a DHHC cysteine-rich domain protein of Akr1p was identified as a palmitoyl transferase, to dual modify the casein kinase Yck2p at its C-terminal –CC– sequences (Roth et al., 2002; Dietrich and Ungermann, 2004). Also, H-Ras was verified to be dual palmitoylated at its –CXXC– motif (Hancock et al., 1989). Based on the experimental observations, we classified the known palmitoylation sites into three clusters, including Type I (sites follow a –CC– pattern, C is a cysteine residue), Type II (sites follow a –CXXC– pattern, C is a cysteine residue and X is a random residue) and Type III (other sites) cluster. Although several other motifs were also proposed, we adopted only the two major motifs for protein palmitoylation by performance comparisons. To improve the prediction performance, we also developed a simple method of MaM. By exhaustively testing, we fixed the Sp as 85% to improve the Sn by MaM. Successfully, both of the Loo validation and the performance on the new data set were greatly improved (Table I). Also, the Ac of Loo validation is very similar with the performance on the new data set. In this regard, the CSS-Palm 2.0 system is accurate and robust.

Table I.

The performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 was greatly improved by matrix mutation (MaM)

| CSS-Palm 2.0 | Threshold | Leave-one-out |

New data set |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac (%) | Sn (%) | Sp (%) | MCC (%) | Ac (%) | Sn (%) | Sp (%) | MCC | ||

| Before MaMa | High | 88.68 | 77.19 | 91.30 | 0.6495 | 89.00 | 56.60 | 93.82 | 0.5084 |

| Medium | 82.38 | 82.89 | 82.26 | 0.5541 | 81.91 | 69.81 | 83.71 | 0.4256 | |

| Low | 69.43 | 87.83 | 65.22 | 0.4153 | 71.88 | 75.47 | 71.35 | 0.3303 | |

| After MaMb | High | 89.60 | 77.19 | 92.43 | 0.6709 | 89.49 | 56.60 | 94.38 | 0.5227 |

| Medium | 85.92 | 82.89 | 86.61 | 0.6142 | 86.31 | 73.58 | 88.20 | 0.5207 | |

| Low | 77.00 | 87.83 | 74.52 | 0.5024 | 76.28 | 81.13 | 75.56 | 0.4089 | |

Both of the leave-one-out validation and the performance on the new data set were calculated and shown.

aPerformance before MaM.

bThe performance after MaM.

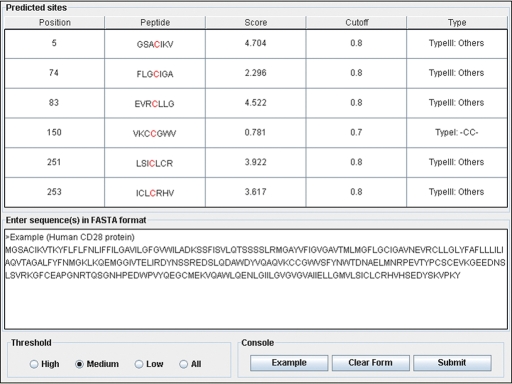

Finally, the online service and local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0 was implemented in JAVA 1.4.2 (J2SE). As an instance, the prediction results of human CD82 was shown (Fig. 2). The human CD82 (UniProt accession number: P27 701), also called as KAI1, is a member of tetraspanin superfamily. Palmitoylation of CD82/KAI1 plays an essential role in inhibiting the migration and invasion of cancer cells (Zhou et al., 2004). The experimentally verified palmitoylation sites on CD82/KAI1 were mapped at position 5, 74, 83, 251 and 253 (Zhou et al., 2004). With the default threshold (medium threshold), the CSS-Palm 2.0 could correctly predict the five sites as positive hits (Fig. 2). In addition, the C150 was also predicted as a positive hit to follow a –CC– (Type I) pattern. Thus, this site might also be a highly potential palmitoylation site and need further experimental verifications.

Fig. 2.

The snapshot of CSS-Palm 2.0 JAVA applet. The prediction results of human CD28 protein were shown as an instance.

Comparison of CSS-Palm 2.0 with previous tools

Here, we compared the prediction performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 to CSS-Palm 1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0. Previously, the NBA-Palm 1.0 was compared with CSS-Palm 1.0 on an old data set (210 experimental sites in 83 proteins) (Xue et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2006). Since the training data set of CSS-Palm 2.0 is much larger than previous tools, it is not strange that the performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 is much higher on the training data set. To dissect whether the updated algorithm of CSS-Palm 2.0 is superior, we re-trained the CSS-Palm 2.0 with the old data set. The default thresholds were chosen for CSS-Palm 1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0, respectively. Then, we fixed the Sn values of CSS-Palm 2.0 to be identical with previous tools and compared the Sp values (Table II). The prediction performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 was greatly improved against previous tools on the old data set. In this regard, the updated CSS algorithm was more useful and accurate. Also, we compared the prediction performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 with previous tools on the new data set (Table II). Again, the prediction results of CSS-Palm 2.0 were much better than the previous tools. Taken together, we proposed that CSS-Palm 2.0 would be more useful for experimentalists.

Table II.

Comparisons of CSS-Palm 2.0 with CSS-Palm 1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0

| Predictor | Old data set |

New data set |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac (%) | Sn (%) | Sp (%) | MCC (%) | Ac (%) | Sn (%) | Sp (%) | MCC | |

| CSS-Palm 2.0 | 88.81 | 82.38 | 90.68 | 0.6982 | 89.49 | 64.15 | 93.26 | 0.5527 |

| 90.31 | 67.62 | 96.94 | 0.7082 | 92.42 | 43.40 | 99.72 | 0.6161 | |

| CSS-Palm 1.0 | 82.94 | 82.16 | 83.17 | 0.5877 | 81.42 | 64.15 | 83.99 | 0.3887 |

| NBA-Palm 1.0 | 86.67 | 67.46 | 92.25 | 0.6102 | 88.26 | 43.40 | 94.94 | 0.4287 |

The old data set included 210 palmitoylation sites from 83 proteins (Zhou et al., 2006), while the new data set contained 53 palmitoylation sites in 26 proteins. The default thresholds were chosen for CSS-Palm 1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0. Then we fixed the Sn values of CSS-Palm 2.0 to be identical with previous tools and compared the Sp values.

Annotation of palmitoylated proteins in budding yeast

Recently, Roth et al. (2006) carried out a large-scale experiment to identify palmitoylated proteins in S. cerevisae. Totally, there were 16 known palmitoylated proteins and 35 novel palmitoylated proteins reported. Then, we used the CSS-Palm 2.0 with high threshold to predict potential palmitoylation sites for these known and novel palmitoylated proteins (Table III). Under the high threshold, the Ac, Sn, Sp and MCC of CSS-Palm 2.0 were 89.60, 77.19, 92.43 and 0.6709, respectively. Successfully, CSS-Palm 2.0 could predict 12 of 16 (75%) known palmitoylated proteins with at least one site. And 26 of 35 (∼74%) novel palmitoylated proteins were predicted with at least one site.

Table III.

The prediction results for 16 known palmitoylated proteins and novel palmitoylated proteins in budding yeast

| Protein | UniProt | Exp. sites | Predicted sites | Predicted palmitoylated peptides |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known palmitoylated proteins | ||||

| Ras1 | P01119 | 305 | 305, 306, 309 | 303-GGCCIIC-309 |

| Ras2 | P01120 | 318 | 318, 319 | 316-GGCCIIS–322 |

| Ste18 | P18852 | 106 | 56, 106, 107 | 55-ACL-57, 104-SVCCTLM-110 |

| Gpa1 | P08539 | 3 | 3 | 1-MGCTV-5 |

| Vac8 | P39968 | 4, 5, 7 | 4, 5, 7, 106, 149 | 4-CCSCLK-9, 105-ACA-107, 148-GCI-150 |

| Gpa2 | P10823 | 4 | 2-GLCAS-6 | |

| Yck1 | P23291 | 537, 538 | 534-KLGCC-538 | |

| Yck2 | P23292 | 545, 546 | 545, 546 | 542-KLGCC-546 |

| Yck3 | P39962 | 517, 518, 519, 520, 522, 523, 524 | 515-KYCCCCFCCC-524 | |

| Bet3 | P36149 | 80 | 80 | 78-PRCEN-82 |

| Lcb4 | Q12246 | 43, 46 | 43, 46, 358, 359 | 41-LSCLSCLD-48, 356-LMCCS-360 |

| Akr1 | P39010 | 443, 598 | 441-PGCLP-445, 596-QICKG-600 | |

| Snc1 | P31109 | 95 | ||

| Snc2 | P33328 | |||

| Tlg1 | Q03322 | |||

| Syn8 | P31377 | |||

| Novel palmitoylated proteins | ||||

| Rho2 | P06781 | 188 | 188, 189 | 186-ANCCIIL–192 |

| Rho3 | Q00245 | 5 | 5, 228 | 3-FLCGS-7, 226-SSCTI-230 |

| Ycp4 | P25349 | 243, 244 | 241-LSCCTVM-247 | |

| Psr1 | Q07800 | 9, 10 | 7-ILCCSS-12 | |

| Psr2 | Q07949 | 9, 10 | 7-ILCCSS-12 | |

| Meh1 | Q02205 | 7, 8 | 5-LSCCRN-10 | |

| Ygl108c | P53139 | 4 | 2-GLCGS-6 | |

| Ypl236c | Q12003 | 13, 14, 15 | 11-NLCCCRG-17 | |

| Lsb6 | P42951 | 607 | 605-TWC-607 | |

| Ypl199c | Q08954 | 235 | 231-IFCNCIQ-237 | |

| Ykl047w | P36090 | 511, 516 | 509-PECLGNLC-516 | |

| Ybr016w | P38216 | 119, 122 | 117-ALCICCTM-124 | |

| Pin2 | Q12057 | 4, 66, 79, 81, 82, 84 | 3-VCK-5, 65-TCF-67, 77-FICWCCRC-84 | |

| Sna4 | Q07549 | 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 | 1-MCCYCVCCTV-10 | |

| Mnn1 | P39106 | 17 | 15-RSCTIP-20 | |

| Ylr001c | Q07895 | 780 | 778-LFCII-782 | |

| Mlf3 | P32047 | 2, 450 | 1-MCVYKS-5, 447-FNSCDT-452 | |

| Mse1 | P48525 | 12, 169 | 10-SYCSP-14, 167-RCCAHL-172 | |

| Nuc1 | P08466 | 2 | 1-MCSRI-5 | |

| Sso1 | P32867 | |||

| Sso2 | P39926 | |||

| Vam3 | Q12241 | |||

| Tlg2 | Q08144 | |||

| Mnn10 | P50108 | |||

| Mnn11 | P46985 | |||

| Tvp18 | A6ZMD0 | |||

| Ylr326w | Q06170 | |||

| Amino acid permeases (AAPs) | ||||

| Agp1 | P25376 | |||

| Bap2 | P38084 | 609 | 435, 609 | 433-IVCCVF-438, 607- FWC-609 |

| Gap1 | P19145 | 397, 602 | 395-YACSR-399, 600-FWC-602 | |

| Gnp1 | P48813 | 663 | 193, 663 | 191-GSCVY-195, 601-FWC-603 |

| Hip1 | P06775 | 603 | 339, 397, 400, 603 | 338-GCL-340, 397-CSRC-400, 601-FWC-603 |

| Sam3 | Q08986 | 123, 377, 587 | 122-FCV-124, 376-SCV-378, 585-FWC-587 | |

| Tat1 | P38085 | 619 | 619 | 617-FWC-619 |

| Tat2 | P38967 | 289, 592 | 288-TCL-290, 590-FWC-592 | |

The predicted palmitoylation sites were marked in bold underline. The experimentally verified sites were taken from UniProt annotation or scientific literature. Eight amino acid permeases (AAPs) were proposed to be palmitoylated at C-teminal cysteines (Roth et al., 2006).

Also, for the known palmitoylated proteins, we searched the UniProt database and scientific literature for their palmitoylation sites information. The ambiguous information with ‘By similarity’, ‘Potential’ and ‘Probable’ in UniProt database was not adopted. In our results, most of real palmitoylation sites were correctly predicted by CSS-Palm 2.0 (Table III). Only one site of Snc1 C95 was missed. And our predictions provided additional information and were useful for further experimental design. For example, although Yck1, Yck2 and Yck3 were verified as palmitoylated proteins, only the palmitoylation sites in Yck2 were clearly mapped as C545 and C546 (Roth et al., 2006). Our prediction results proposed that Yck1 and Yck3 might be palmitoylated at C537, C538 and C517, C518, C519, C520, C522, C523 and C524, respectively. Again, although Gpa2 was proposed as a real palmitoylated protein, its palmitoylation sites information is still ambiguous (Roth et al., 2006). Our results suggested that Gpa2 might be palmitoylated on a single cysteine residue at position 4 (Table III).

In the novel palmitoylated proteins, the palmitoylation sites on Rho2 and Rho3 were mapped at C188 and C5, respectively (Roth et al., 2006). Our results could correctly predict these sites as positive hits (Table III). Again, eight amino acid permeases (AAPs) including Agp1, Bap2, Gap1, Gnp1, Hip1, Sam3, Tat1 and Tat2 were suggested to be palmitoylated at C-teminal cysteines (Table III) (Roth et al., 2006). And our results predicted most of these C-terminal cysteine residues as positive hits.

Furthermore, Roth et al. (2006) suggested a novel sequence pattern for palmitoylation recognition. Thirteen palmitoylated proteins, including Snc1, Snc2, Tlg1, Syn8, Sso1, Sso2, Vam3, Tlg2, Mnn10, Mnn11, Pin2, Mnn1 and Ylr001c (Table III), were proposed to be potentially palmitoylated at cysteines cytoplasmically adjacent to their single transmembrane domains. However, these potential palmitoylation sites were still not experimentally verified during the past one and a half year. Thus, the new sequence pattern for palmitoylation was not adopted in current CSS-Palm 2.0. And the CSS-Palm 2.0 with high threshold generated only poor prediction on these proteins. We believed that the prediction performance of CSS-Palm 2.0 will be improved if these potential sites were experimentally verified and included into training data set.

Discussion

In this work, we updated our previous CSS algorithm with great improvement (Zhou et al., 2006). First, the experimentally verified palmitoylation sites were classified into three clusters, including Type I (sites follow a –CC– pattern, C is a cysteine residue), Type II (sites follow a –CXXC– pattern, C is a cysteine residue and X is a random residue) and Type III (other sites) cluster. Both of training and prediction processes were separately performed on three types of palmitoylation sites. Also, the threshold values for three types of sites were different, dependent on final prediction performance. In addition, we developed a simple method as MaM to improve the prediction performance of CSS-palm 2.0.

Although it is very fast to predict potential palmitoylation sites for a single protein sequence, the speed of previous tools will be greatly slowed down if several users input multiple sequences simultaneously for prediction. Thus, both CSS-Palm 1.0 and NBA-Palm 1.0 only permitted a few proteins (<100) in FASTA format as input. The CSS-palm 2.0 was implemented in JAVA and used local CPU for computation. Thus, the calculating time is dependent on the users’ computers. Also, the code of CSS-Palm 2.0 was greatly optimized. We tested the speed of CSS-palm 2.0 on a variety of computers. Even on a laptop (e.g. IBM ThinkPad R51, 1.60 GHz, 768 MB), CSS-palm 2.0 will predict out potential palmitoylation sites for ∼1000 proteins (average length ∼1000 amino acids) within 3 min. Thus, the CSS-palm 2.0 is more convenient for a large-scale scan. Moreover, the local packages of CSS-Palm 2.0 were developed and could support three major OSs, including Windows, Linxu/Unix and Mac.

As an application of CSS-Palm 2.0, we annotated the palmitoylation sites information for palmitoylated proteins in budding yeast. These substrates were generated from a large-scale experiment (Roth et al., 2006). And the palmitoylation sites in most of these proteins are not experimentally verified. Our results could accurately predict out the known palmitoylation sites. Furthermore, our predictions provided more information and were useful for further experimental consideration. Taken together, we proposed that CSS-Palm 2.0 will be more useful for its fast-speed and superior performance.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Chinese 973 project (2002CB713700, 2006CBOF0503 and 2006CB933300), Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX1-YW-R65, KSCX2-YW-21 and KJCX2-YW-M02), Chinese Natural Science Foundation (39925018, 30270293, 90508002 and 30700138) and National Institutes of Health (DK56292). Dr. Xuebiao Yao is a GCC Eminent Scholar.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. The authors thank Kai Yuan and Dezhi Hou for their evaluation of the CSS-Palm 2.0 beta version. The authors also thank Dr. Christopher Korey (Charleston, USA) for his constructive suggestions during the CSS-Palm 2.0 development.

Footnotes

Edited by Rebecca Wade

References

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlmakers M.J., Marsh M. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:32–42. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologna G., Yvon C., Duvaud S., Veuthey A.L. Proteomics. 2004;4:1626–1632. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey P.J. Science. 1995;268:221–225. doi: 10.1126/science.7716512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabandhu K., Herincs Z., Huault S., Dost B., Peng L., Conchonaud F., Marguet D., He H.T., Hueber A.O. EMBO J. 2007;26:209–220. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich L.E., Ungermann C. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper J.M., Xia Z., Smith C.D. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:1873–1884. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700179-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhaber B., Bork P., Eisenhaber F. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:741–758. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhaber F., Eisenhaber B., Kubina W., Maurer-Stroh S., Neuberger G., Schneider G., Wildpaner M. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3631–3634. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhaber B., Schneider G., Wildpaner M., Eisenhaber F. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;337:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Husseini Ael D., Bredt D.S. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:791–802. doi: 10.1038/nrn940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser N., Maser P. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1846–1852. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves J., Chamberlain L.H. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:249–254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J.F., Magee A.I., Childs J.E., Marshall C.J. Cell. 1989;57:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Godzik A. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder M.E., Deschenes R.J. Nat. Rev. 2007;8:74–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer-Stroh S., Eisenhaber B., Eisenhaber F. J. Mol.Biol. 2002;317:541–557. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer-Stroh S., Eisenhaber B., Eisenhaber F. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:523–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer-Stroh S., Eisenhaber F. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R55. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-6-r55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadolski M.J., Linder M.E. FEBS J. 2007;274:5202–5210. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podell S., Gribskov M. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh M.D. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh M.D. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nchembio834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A.F., Feng Y., Chen L., Davis N.G. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159:23–28. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A.F., Wan J., Bailey A.O., Sun B., Kuchar J.A., Green W.N., Phinney B.S., Yates J.R., III, Davis N.G. Cell. 2006;125:1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotrys J.E., Linder M.E. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:559–587. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J., Roth A.F., Bailey A.O., Davis N.G. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1573–1584. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y., Chen H., Jin C., Sun Z., Yao X. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:458. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., Liu L., Reddivari M., Zhang X.A. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7455–7463. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Xue Y., Yao X., Xu Y. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:894–896. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]