Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alberta Blue Cross (ABC) provides copayment-based coverage for residents older than 65 years. A prior authorization (PA) process for patients prescribed clopidogrel following stent insertion was changed to an authorized prescriber (AP) list process in March 2002.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the effect of a policy change in medication coverage for clopidogrel on patients’ filling of prescriptions and outcomes following stent insertion.

METHODS

Consecutive patients who received a coronary stent between September 1, 2001, and August 31, 2002, at the University of Alberta Hospital and were eligible for ABC coverage were identified. Data were obtained from the Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease and ABC databases.

RESULTS

One hundred twelve patients (45 in the PA period and 67 in the AP period) who received a coronary stent were eligible for ABC coverage during the study period. The two cohorts of patients were similar with respect to demographics. Fewer patients in the PA period than in the AP period had their prescription filled on the day of discharge (31% versus 54%; P=0.02), and the median time to fill was four days versus zero days in the PA and AP periods, respectively (Wilcoxon P=0.04). There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients filling their prescriptions after 28 days from discharge (67% versus 75%, P = not significant) or in the overall comparison of time to fill (log rank P=0.22). Two repeat revascularization procedures were necessary within six weeks after stent placement; both were in PA period patients who delayed or failed to fill their prescription.

CONCLUSIONS

The PA process may have delayed patients filling clopidogrel prescriptions following hospital discharge and has the potential to contribute to negative clinical consequences.

Keywords: Clopidogrel, Drugs, Patients, Prior authorization, Stents

Abstract

HISTORIQUE

La Croix-Bleue de l’Alberta (CBA) offre une couverture par quote-part aux résidents de plus de 65 ans. En mars 2002, un processus d’autorisation préalable (AP) pour les patients à qui on prescrivait du clopidogrel après l’installation d’une endoprothèse est devenu un processus de liste de prescripteurs autorisés (PA).

OBJECTIF

Déterminer l’effet d’une modification à la couverture d’assurance du clopidrogel sur l’exécution des ordonnances des patients et sur leur issue après l’installation d’une endoprothèse.

MÉTHODOLOGIE

On a repéré les patients consécutifs à qui on avait installé une endoprothèse coronaire entre le 1er septembre 2001 et le 31 août 2002 au University of Alberta Hospital et qui étaient admissible à la couverture de la CBA. On a obtenu les données auprès de l’Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease et des bases de données de la CBA.

RÉSULTATS

Cent douze patients (45 pendant la période d’AP et 67 pendant celle des PA) à qui on avait installé une endoprothèse coronarienne étaient admissibles à la couverture de la CBA pendant la période de l’étude. Les deux cohortes de patients étaient similaires du point de vue de la démographie. Moins de patients de la période d’AP que de celle des PA avaient fait exécuter leur ordonnance le jour de leur congé (31 % par rapport à 54 %, p = 0,02), et le temps médian pour la faire exécuter était de quatre jours pendant la période d’AP par rapport à 0 jour pendant celle de PA (p de Wilcoxon = 0,04). Il n’y avait pas de différence significative dans la proportion de patients qui faisaient exécuter leur ordonnance plus de 28 jours après leur congé (67 % par rapport à 75 %, p = non significatif) ou dans la comparaison globale du temps d’exécution (p du test logarithmique par rangs = 0,22). Il a fallu effectuer deux revascularisations dans les six semaines suivant l’installation de l’endoprothèse, toutes deux pendant la période d’AP, chez des patients qui avaient tardé à faire exécuter leur ordonnance.

CONCLUSIONS

Le processus d’AP peut avoir incité les patients à tarder à faire exécuter leur ordonnance de clopidrogel après leur congé de l’hôpital, ce qui risque de favoriser des conséquences cliniques négatives.

Clopidogrel, in combination with acetylsalicylic acid, is currently recommended as the standard of care following stent insertion for the prevention of subacute stent thrombosis (1). Stent thrombosis occurs early following the procedure and can result in complications, including death, myocardial infarction and the need for urgent coronary artery bypass grafting or repeat percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). It differs from restenosis, which is a late, proliferative process (1). All residents of Alberta older than 65 years of age are eligible to apply for copayment-based coverage by Alberta Blue Cross (ABC) for products on the provincial drug benefit list. Clopidogrel received its notice of compliance in Canada in October 1998, but was not on the benefit list in Alberta. Instead, from January 15, 2000, to March 1, 2002, a prior authorization (PA) process mandated that a special authorization form be completed and faxed to ABC for each patient requiring clopidogrel. Several working days could be required to complete the PA process and allow successful adjudication of the claim. Authorization forms were not processed during weekends or statutory holidays, and due to this delay, some patients may have been required to pay the entire cost of their prescription at the time of filling, with the possibility of reimbursement at a later date.

We had concerns about the impact of the PA process on patient decisions to fill a prescription for clopidogrel and the timeliness with which it occurred, and hypothesized that it could lead to potentially deleterious delays in patients filling their prescriptions. As of March 1, 2002, a change in policy allowed certain authorized prescribers (all cardiologists) to prescribe a 28-day supply of clopidogrel following the first coronary stent insertion. This policy change provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact of PA processes on patient compliance and clinical outcomes.

METHODS

The primary objective of the present study was to retrospectively examine the effect of a policy change for clopidogrel from the time of the PA process to that of the authorized prescriber (AP) list process on the filling of prescriptions following intracoronary stent insertion. Secondary objectives included the effects of this change on timeliness of prescription filling and on clinical consequences, as measured by repeat target vessel revascularization.

The Alberta Provincial Project for Outcomes Assessment in Coronary Heart disease (APPROACH) is a clinical data collection initiative that captured all patients who underwent cardiac catheterization in Alberta since 1995 (2). APPROACH contains detailed clinical data and coronary anatomy information, and also tracks therapeutic interventions, including repeat revascularization procedures. Follow-up mortality is ascertained through semi-annual linkage to data from the Alberta Vital Statistics bureau.

APPROACH was used to identify consecutive patients older than 65 years of age (and therefore potentially eligible for ABC coverage) who received an intracoronary stent at the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton and a first prescription for clopidogrel, and who were discharged during the PA process period (September 1, 2001, to February 28, 2002) or the AP process period (March 1, 2002, to August 31, 2002). The first stent insertion during the study period was considered the index event. Patients undergoing staged procedures were excluded, as were those transferred to another hospital postprocedure and those who resided in long-term care facilities. Medical records were reviewed to verify residence in Alberta, clopidogrel prescriptions, patient characteristics and clinical data, and the provision of pass or discharge medications. The present study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta.

Because patients must apply for coverage, eligibility was confirmed by ABC. For patients receiving prescriptions in the PA process period, ABC provided the dates on which the authorization forms were received and approved, as well as the dates of the prescription fills. ABC provided only the prescription fill dates for patients in the AP period.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups were conducted using Student’s t test for continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test (when cell counts were less than five) for discrete variables. Time to prescription fill was calculated as the difference between the date of hospital discharge and that of the first clopidogrel prescription fill. This variable was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with patients who had not filled a prescription censored at 60 days after discharge.

RESULTS

Seven hundred thirteen patients underwent PCI at the University of Alberta Hospital during the study period, 274 of whom were older than 65 years of age. After applying the exclusion criteria (ie, staged procedures, hospital transfers, residence in a long-term care facility, previous therapy with clopidogrel and death), the study sample comprised 112 patients who were covered by ABC’s Senior Plus plan and received an intracoronary stent. Forty-five of these patients underwent PCI in the PA period, and 67 did so in the AP period. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The two groups were very similar with respect to the demographics and clinical data examined. The majority of patients underwent cardiac catheterization and PCI for high-risk clinical conditions (acute coronary syndromes and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction). Medications at discharge included the standard cardioprotective agents, which were also similar between the two groups. Clopidogrel was not supplied as a pass or discharge medication for any patients.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics and clinical data

| Patient characteristics and clinical data | Prior authorization period (n=45) | Authorized prescriber period (n=67) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD, years | 74±6 | 74±6 |

| Male, n (%) | 34 (76) | 49 (73) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 26 (58) | 50 (75) |

| Hypertension | 24 (53) | 41 (61) |

| Former smoker | 17 (38) | 33 (49) |

| Current smoker | 7 (16) | 8 (12) |

| Family history | 16 (36) | 19 (28) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (29) | 18 (27) |

| Indication for procedure, n (%) | ||

| Acute coronary syndromes* | 22 (49) | 27 (40) |

| Stable angina | 10 (22) | 24 (36) |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 11 (24) | 16 (24) |

| Other | 2 (4) | 0 |

| Target vessel (not mutually exclusive), n (%) | ||

| Left anterior descending artery | 24 (53) | 25 (37) |

| Left circumflex coronary artery | 7 (16) | 9 (13) |

| Right coronary artery | 18 (40) | 28 (42) |

| Ramus artery | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Saphenous vein graft/left internal mammary artery | 4 (9) | 7 (10) |

| Diagonal artery | 2 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Obtuse marginal artery | 3 (7) | 4 (6) |

| Medications at discharge, n (%) | ||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 41 (91) | 61 (91) |

| ACE inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blockers | 37 (82) | 53 (79) |

| Beta-blockers | 39 (87) | 56 (84) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 7 (16) | 13 (19) |

| Long-acting nitrates | 6 (13) | 13 (19) |

| Lipid-lowering therapy | 31 (69) | 50 (75) |

Acute coronary syndromes include unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. ACE Angiotensin-converting enzyme

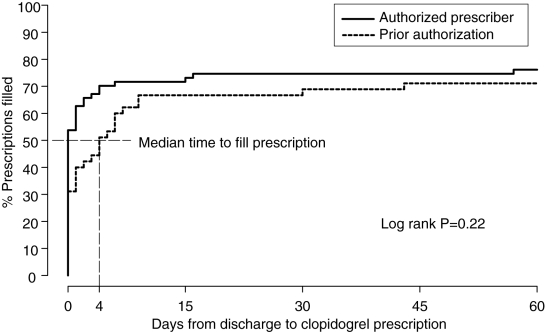

Fewer patients in the PA period than in the AP period had their prescription for clopidogrel filled on the day of discharge (31% versus 54%; P=0.02). The median time to fill was four days versus zero days in the PA and AP periods, respectively (Wilcoxon P=0.04) (Figure 1). This early difference was gradually reduced, with no significant difference in the proportion of patients filling their prescriptions by 28 days (67% versus 75%; P = not significant) or in the overall comparison of time to fill (log rank P=0.22). It is notable that only 71% of patients in the PA period and 76% of those in the AP period had their prescriptions filled within 60 days of discharge.

Figure 1.

Time delay to filling of clopidogrel prescription from day of discharge as measured by per cent prescription filled

Clinically driven, repeat revascularizations were performed in six patients within a six-month period, all from the PA period. Two of these occurred within six weeks of the index stent insertion. One patient failed to fill their prescription and suffered an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction due to acute stent thrombosis. The other patient delayed filling their prescription by six days and presented with an acute coronary syndrome. In the latter case, ABC received the special authorization form two days postdischarge.

DISCUSSION

We observed a significant delay in the filling of clopidogrel prescriptions under the PA system compared with the new AP process, and this delay placed patients at risk. Indeed, we observed two repeat revascularizations that were likely due to these delays. A more global problem was that fewer than three-quarters of patients in both groups filled their clopidogrel prescriptions within 60 days of discharge.

Given the rising costs of pharmaceuticals and the significant proportion of the population covered by some form of drug benefit insurance, there is a great deal of interest in the impact of drug coverage on drug use, health care costs and health outcomes. Unfortunately, the majority of studies exploring these questions suffer from methodological flaws, including poor data quality and availability, selection bias, lack of applicability and failure to consider clinical outcomes.

The PA process restricts the use of prescription drugs by requiring approval from the insurer before dispensing, and it is widely used in Canada and the United States. In general, the PA process targets high-cost drugs restricted for use in specific clinical situations or patient criteria (such as clopidogrel post-stent insertion); specific, effective drugs for which there are less costly therapeutic alternatives; and step therapy programs that require a previous trial of another agent (3,4). It is frequently stressed that the PA process must be timely and that it may not be appropriate for all classes of medications or medical conditions. The traditional program, which was used by ABC in the present study, requires staff adjudication of individual cases according to established criteria. Online adjudication with computer decision trees has been explored as a means of improving efficiency (3,5).

There have been several previous studies assessing PA processes. However, they have tended to focus on medications for chronic conditions, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (6–8) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (9). Most of these did not assess clinical outcomes, and those that did were hampered by poor survey response rates. In our study, the PA process was used for acute indication, and we demonstrated significant potential for unintended negative clinical outcomes.

The change to an AP process improved patient access to therapy. Nevertheless, only three-quarters of patients filled their prescription for clopidogrel, leaving at least one-quarter at unacceptably high risk for subacute stent thrombosis. This finding was unexpected and requires further investigation.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations associated with the present study. The partially controlled design does not provide the same level of causal inference as a randomized controlled trial. A comparison group that did not have this change in coverage was not available, so exogenous political or social changes affecting the outcomes of interest would not have been detected. The present retrospective study did not examine either patient education or discharge instructions, nor was the socioeconomic status of each patient ascertained. However, there were no other known initiatives concerning these clinical areas identified during the study period. As in all nonrandomized studies, there was potential for a selection bias. However, the ABC policy change provided the unique opportunity to study the impact of PA procedures in a real-life setting, in which a randomized trial is unlikely to be conducted. Although the inclusion of patients older than 65 years of age may have limited the applicability of our results, this population is a major user of health care resources, is restricted by a fixed income and is commonly covered by government-based insurance. It was not possible to ascertain whether any patients who delayed their prescription fill were provided samples or used a spouse’s prescription, or whether patients were provided a portion of their prescription at no charge by the community pharmacy until authorization was received. Chart review determined that no patient had been supplied with pass or discharge clopidogrel. The availability of private supplemental health insurance coverage was not determined. However, in the majority of cases, this coverage is not applied until ABC rejects a claim or a portion thereof. Finally, the ABC database only supplied information on the patient collecting the prescription, with no measure of adherence thereafter.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study verifies health care professionals’ concerns that the PA process may have delayed patient access to necessary medications and has the potential for negative clinical consequences. It is apparent that such processes must be timely and may not be appropriate for all classes of medications or medical conditions. Our research supports the need for more well-controlled studies on the effects of medication coverage on health outcomes and the requirement for an evaluation of the effects of policy changes when they are implemented.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was partially supported by a research grant from the Institute of Health Economics, Edmonton, Alberta, and conducted by the Epidemiology Coordinating and Research Centre, as well as the Centre for Community Pharmacy Research and Interdisciplinary Strategies, Faculty of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton. The authors acknowledge Patrick Rurka, BScPharm, and Sandra Blitz, MSc, for their invaluable assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith SC, Jr, Dove JT, Jacobs AK, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (committee to revise the 1993 guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty); Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. ACC/AHA guidelines for percutaneous coronary intervention (revision of the 1993 PTCA guidelines) – executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (committee to revise the 1993 guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) endorsed by the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2001;103:3019–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.24.3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghali WA, Knudtson ML. Overview of the Alberta provincial project for outcome assessment in coronary heart disease. On behalf of the APPROACH investigators. Can J Cardiol. 2000;16:1225–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips CR, Larson LN. Evaluating the operational performance and financial effects of a drug prior authorization program. J Managed Care Pharm. 1997;3:699–706. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lexchin J. Effects of restrictive formularies in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2001;8:69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kielty M. Improving the prior-authorization process to the satisfaction of customers. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1499–501. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.15.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smalley WE, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Sullivan L, Ray WA. Effect of a prior-authorization requirement on the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs by Medicaid patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1612–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506153322406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotzan JA, McMillan JA, Jankel CA, Foster AL. Initial impact of a Medicaid prior authorization program for NSAID prescriptions. J Res Pharm Econ. 1993;5:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Momani AA, Madhavan SS, Nau DP. Impact of NSAIDs prior authorization policy on patients’ QoL. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1686–91. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCombs JS, Shi L, Stimmel GL, Croghan TW. A retrospective analysis of the revocation of prior authorization restrictions and the use of antidepressant medications for treating major depressive disorder. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1939–59. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80090-x. discussion 1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]