Abstract

Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (hGM-CSF) induces proliferation and sustains the viability of the mouse interleukin-3-dependent cell line BA/F3 expressing the hGM-CSF receptor. Analysis of the antiapoptosis activity of GM-CSF receptor βc mutants showed that box1 but not the C-terminal region containing tyrosine residues is essential for GM-CSF-dependent antiapoptotic activity. Because βc mutants, which activate Janus kinase 2 but neither signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 nor the MAPK cascade sustain antiapoptosis activity, involvement of Janus kinase 2, excluding the above molecules, in antiapoptosis activity seems likely. GM-CSF activates phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase as well as Akt, and activation of both was suppressed by addition of wortmannin. Interestingly, wortmannin did not affect GM-CSF-dependent antiapoptosis, thus indicating that the phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase pathway is not essential for cell surivival. Analysis using the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein and a MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase 1 inhibitor, PD98059, indicates that activation of either the genistein-sensitive signaling pathway or the PD98059-sensitive signaling pathway from βc may be sufficient to suppress apoptosis. Wild-type and a βc mutant lacking tyrosine residues can induce expression of c-myc and bcl-xL genes; however, drug sensitivities for activation of these genes differ from those for antiapoptosis activity of GM-CSF, which means that these gene products may be involved yet are inadequate to promote cell survival.

INTRODUCTION

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a cytokine that stimulates proliferation, differentiation, and survival of various hematopoietic cells (Arai et al., 1990). Receptors of interleukin 3 (IL-3) and GM-CSF consist of two subunits, α and β, both of which are members of the cytokine receptor superfamily (Miyajima et al., 1993). The α subunit is specific for each cytokine, and the β subunit (βc) is shared by IL-3, GM-CSF, and IL-5 (Miyajima et al., 1993). IL-3 and GM-CSF induce tyrosine phosphorylation of βc and various cellular proteins, activate early response genes, and also activate cell proliferation in hematopoietic cells and in fibroblasts (Watanabe et al., 1993a). IL-3 and GM-CSF receptors (GMRs) do not contain a kinase domain or any other enzymatic activity in the receptor itself. However, data suggesting the primary role of Janus kinase (JAK) 2 in IL-3 or GM-CSF signals have accumulated (Brizzi et al., 1994; Quelle et al., 1994). Using a dominant negative JAK2, we showed that JAK2 plays an essential role in GM-CSF induced proliferation, induction of immediate early genes, phosphorylation of cellular proteins and βc itself (Watanabe et al., 1996). We then made attempts to determine the signaling pathway of human (h) GM-CSF, using various βc mutants (Watanabe et al., 1993b, 1995a,b; Itoh et al., 1996). βc contains the conserved box1, box2 regions in addition to eight tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic region (Hayashida et al., 1990). We and others constructed a series of C-terminal deletion mutants (Sakamaki et al., 1992; Itoh et al., 1996), internal deletions of the box1, box2 regions, and a series of mutants in which βc tyrosine residues were converted to phenylalanine (Okuda et al., 1997; Itoh et al., 1998). By analyzing these mutants in BA/F3 cells and NIH3T3 cells, we found that multiple signaling pathways are activated by hGMR. Among the mutants, the Fall mutant in which βc tyrosine residues are all converted to phenylalanine is unique, because cell survival can be sustained, yet cell proliferation is impaired (Okuda et al., 1997; Itoh et al., 1998). Adding back any single βc tyrosine residue restored full activity of proliferation promotion, indicating that tyrosine residues are required for full proliferation but not for cell survival in BA/F3 cells.

Although signaling events and mechanisms leading to initiation of cell proliferation are largely unknown, much attention has been directed to the mechanism of prevention or promotion of apoptosis. Withdrawal of IL-3 from progenitor cell lines or primary IL-3-dependent cells or bone marrow cells resulted in apoptosis (Williams et al., 1990; Collins et al., 1992). There are several mouse (m) IL-3- or hGM-CSF-dependent cell lines such as 32D and BA/F3 cells, which are appropriate models for the study of apoptosis. In these cells, apoptosis was triggered by factor depletion. Several attempts to elucidate the mechanism of IL-3- or GM-CSF-induced antiapoptosis activity were made, and involvement of various molecules became evident. Bcl-2 protein is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein (Hockenberry et al., 1990), and overexpression of the Bcl-2 protein prolongs survival of hematopoietic cells (Vaux et al., 1988; Collins et al., 1992). As a member of the Bcl-2 family, Bcl-xL has been implicated in antiapoptosis in BA/F3 cells (Boise et al., 1993). IL-3 can regulate the expression level of Bcl-2 family member proteins (Leverrier et al., 1997). The roles of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase (PI3-K), Akt, a serine-threonine protein kinase, and the BAD pathway have been characterized in several systems, including IL-3 signaling (Franke et al., 1997b). BAD heterodimerizes with Bcl-xL and Bcl-2, neutralizes their protective effects, and promotes cell death (Franke and Cantley, 1997), and this activity is regulated by phosphorylation of BAD, which can be induced by IL-3 through cascade of activation of PI3-K and Akt (Zha et al., 1996; del Peso et al., 1997). In contrast to the documented PI-3K-Akt-Bad cascade, the role of R-ras-MAPK in antiapoptosis has remained to be clarified. Active R-ras binds to PI3-K (Rodriguez-Viciana et al., 1994), but it is still not clear whether PI-3K is downstream of R-ras in cytokine signals. Other authors using the dominant negative MAPK kinase suggested that the MAPK cascade is involved in IL-3 induced bcl-x gene expression (Leverrier et al., 1997), and it was reported that the MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) kinase 1 (MEK1) inhibitor PD98059 suppressed BA/F3 cell survival dependent on the active form of R-ras, which also binds with Bcl-2 (Fernandez-Sarabia and Bischoff, 1993; Suzuki et al., 1997).

Because one can activate or inactivate certain signaling pathway or events of hGM-CSF using large numbers of βc mutants in combination with drugs, we focused on analyzing signals related to cell survival. It became apparent that there are multiple pathways to sustain survival of BA/F3 cells through hGM-CSF receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, Media, and Cytokines

FCS was from Biocell Laboratories (Carson, CA). RPMI 1640 medium was from Nikken BioMedical Laboratories (Kyoto, Japan). Recombinant mIL-3 expressed in silkworm, Bombyx mori, was purified as described elsewhere (Miyajima et al., 1987). Recombinant hGM-CSF and G418 were gifts from Schering-Plough (Union, NJ). Peptides conjugated with fluorescent compounds were purchased from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). PD98059 was from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Wortmannin was from Sigma (Steinheim, Germany), and genistein was purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Mouse bcl-2 and bcl-xL genes were kindly provided by Dr. Y. Tsujimoto (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan).

Cell Lines and Culture Methods

A mIL-3-dependent proB cell line, BA/F3 (Palacios et al., 1985), was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FCS, 0.25 ng/ml mIL-3, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. For depletion of mIL-3, the same medium but without mIL-3 was used (depletion medium). Various BA/F3 cell clones expressing wild-type hGMRα alone (BA/F-α), wild-type hGMRα and hGMRβ (BA/F-wild), or wild-type hGMRα and one of hGMRβ mutants, Fall, 544, 517, Δbox1, and Δbox2 (BA/F-Fall, -544, -517, -Δbox1, and -Δbox2, respectively) were grown in the same type of medium with 500 μg/ml G418.

Incorporation of [3H]Thymidine

BA/F3 cells were seeded in a flat-bottom 96-well plate (1.2 × 104 cells per 200 μl per well) with various concentrations of mIL-3 or hGM-CSF. Cells were cultured for 24 h, and [3H]thymidine for labeling was added (1 μCi/well) for 4 h. Cells were transferred to a filter using a cell harvester (Micro96; Skatron Instruments, Lier, Norway), and 3H incorporation was analyzed using a filter counter (1450 Microbeta Plus; Wallac, Turku, Finland). For long-term proliferation assay, the viable cell number was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion assay.

Analysis of Caspase Enzymatic Activity

Cells (2 × 106) were washed with PBS and lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid-NaOH, pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF) by freezing and thawing three times in liquid N2. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and 10 μl of supernatant were incubated with fluorigenic substrate peptides (final concentration, 1.5 μM) in 2 ml of enzyme reaction buffer (100 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 10% sucrose, 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid, 10 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/ml ovalbumin) for 30 min at 37°C. The peptides conjugated with fluorescent compounds, Ac-YVAD-MCA (Thornberry et al., 1992), MocAc-YVADA PK(Dnp)-NH2 (Enari et al., 1996), Ac-DEVD-MCA, and MocAc-DEVDA PK(Dnp)-NH2 (Enari et al., 1996), were used as specific substrates for enzyme analysis of caspase-1 (YVAD) and caspase-3 (DEVD). Protease activities were determined by monitoring the release of fluorescent compounds, using a spectrofluorophotometer (RF-5300PC; Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). Wavelengths were excitation wavelength of 325 nm and emission wavelength of 392 nm for Dnp and excitation wavelength of 380 nm and emission wavelength of 460 nm for MCA with a band path of 5 nm. Protein concentration of the lysates was determined using BCA protein assay kits (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and fluorescence values were expressed as a value relative to the protein concentration.

DNA Fragmentation Assay

DNA fragmentation assay was done by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated biotinylated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay (Gorczyca et al., 1993) and DNA ladder assay. TUNEL assay was done using Takara Biomedicals (Otsu, Japan) in situ apoptosis detection kits according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, cells (1–3 × 106) were washed with PBS and fixed with 10% of formalin in PBS and further incubated with 0.3% H2O2 and methanol. The cells were then permeabilized and labeled with terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-FITC HRP conjugate and analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). A total of 10,000 events were collected, and ungated data are presented in all figures shown.

Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase (ERK) Western Blotting and c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) Kinase Assay

ERK mobility shift assay was done by Western blotting of total cell lysates, and JNK kinase assay was done using immunoprecipitates of JNK1 and GST-c-Jun, as described (Liu et al., 1997b; Itoh et al., 1998). Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting were done as described (Itoh et al., 1996; Watanabe et al., 1996). Briefly, cells (1 × 107 for kinase assay, 1 × 106 for whole cell lysate) were depleted of mIL-3 for 5 h and then restimulated with hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. In some cases, the cells were precultured with inhibitors, 15 min for genistein (20 μg/ml) and PD98059 (100 μM) before hGM-CSF stimulation. Immunoprecipitation of JNK1 was done using polyclonal antibody anti-JNK1 (C-17; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The precipitate was analyzed by immunoblotting or kinase assay as described (Itoh et al., 1996; Watanabe et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1997). Total cell lysates were used for ERK Western blotting analysis using polyclonal antibody anti-ERK2 (C-14; Santa Cruz).

Northern Blotting

The mRNA used for Northern blotting was prepared using the FastTrack 2.0 kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One microgram of RNA was electrophoresed through a 1.2% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde and then was transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) and fixed by UV cross-linking (Spectrolinker XL-1000 UV cross-linker; Spectronics, Westbury, NY). The membrane was hybridized with cDNA probes (c-myc, bcl-2, and bcl-xL) labeled with [32P]dCTP using random priming kits (Ready To Go; Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The blotted membranes were visualized and quantified using a Fuji (Tokyo, Japan) image analyzer (model BAS-2000).

Analysis of PI3-K and Akt Activities

PI3-K activity associated with antiphosphotyrosine antibody immunoprecipitates was assayed as described (Liu et al., 1999). Briefly, cells (1.5 × 107/sample) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (4G10). Immunoprecipitates were subjected to lipid kinase assays using phosphatidylinositol as a substrate. Products were extracted with CHCl3:MeOH (2:1, vol/vol) and separated by oxalate-treated TLC plates (Silica Gel 60; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) using a solvent system of CHCl3:MeOH:H2O:25% NH4OH (90:65:8:12, vol/vol/vol/vol). PI3-phosphate was visualized by autoradiography, and 32P incorporation was quantified using a Fuji image analyzer (model BAS-2000). Activity of Akt was analyzed by Western blotting of total cell lysates using antiphosphorylated-AKT antibody (Liu et al., 1999).

Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was analyzed by uptake of 3,3′dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6[3]), a fluorochrome that incorporates into cells dependent on their mitochondrial transmembrane potential (Zamzami et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1998). Cells (2 × 105) were collected and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. DiOC6(3) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to final concentration of 10 nM and incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the presence or absence of 50 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (Wako, Osaka, Japan), an uncoupling agent that abolishes ΔΨm.

RESULTS

Tyrosine Residues of βc Are Not Required for Cell Survival of BA/F3 Cells

BA/F3 is an mIL-3-dependent cell line (Palacios and Steinmetz, 1985), which cannot survive without mIL-3, even in the presence of FCS. We have been analyzing signal transduction of hGMR using various βc mutants expressed in BA/F3 cells. There are eight tyrosine residues within the cytoplasmic region of βc. To examine the role of βc tyrosine residues, we constructed a series of βc mutants, in which single or double tyrosine residues remained intact, whereas the others were converted to phenylalanine. Using the mutants, we noted different requirements of tyrosine residues for cell proliferation, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) phosphorylation, and activation of the MAPK cascade (Itoh et al., 1998). In addition, we found that mutant Fall, which has mutations of all tyrosine residues to phenylalanine, supports the survival of BA/F3 cells.

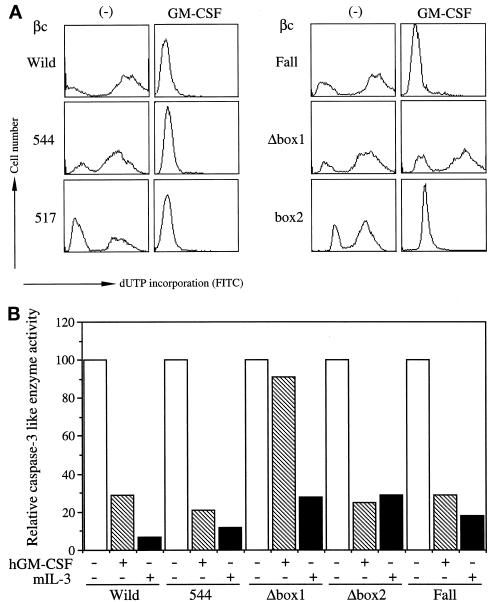

To analyze detailed signaling events of antiapoptosis of hGMR, we first characterized the factor depletion-induced DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay (Gorczyca et al., 1993) using a flow cytometer. DNA fragmentation became evident 4 h after factor depletion, and >80% of the cells showed DNA fragmentation after 24 h (our unpublished results). We next asked whether DNA fragmentation would be suppressed by hGM-CSF through various hGM-CSFR βc mutants. BA/F-wild or BA/F3 cells expressing wild-type α subunits and various βc mutants (BA/F-544, -517, 455, Δbox1, Δbox2, and Fall) were cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml), and DNA fragmentation was examined by TUNEL analysis. As shown in Figure 1A, the addition of hGM-CSF completely blocked DNA fragmentation in BA/F-wild cells. The mutant βc 544 is a C-terminal truncation (Sakamaki et al., 1992) and cannot activate the c-fos promoter (Watanabe et al., 1993b). In BA/F3 cells expressing wild-type α subunit and βc mutant 544 (BA/F-544), DNA fragmentation was also suppressed in the presence of hGM-CSF. The Fall mutant also suppressed apoptosis in the presence of hGM-CSF. The Δbox1 mutant, which lacks amino acid positions 458–465 covering the box1 region of βc and cannot activate any of examined activities of hGM-CSF (Itoh et al., 1996; Watanabe et al., 1996), was unable to suppress the depletion-induced DNA fragmentation. In contrast, the Δbox2 mutant, which lacks the region spanning amino acid positions 518–530 within the box2 region, suppressed DNA fragmentation. Because these results suggested that the box2 region is dispensable, we analyzed the role of box2 using mutant 517, the C-terminal region of which was deleted at amino acid position 517 located between box1 and box2 (Sakamaki et al., 1992). DNA fragmentation was also suppressed when we added hGM-CSF in BA/F-517, results consistent with results obtained from BA/F-Δbox2. Further deletion up to amino acid position 455 resulted in loss of the βc box1 region. Thus, it appeared that βc 455 cannot prevent DNA fragmentation in response to hGM-CSF (our unpublished results), and this adds support to the notion that the box1 region is required.

Figure 1.

Region of βc required for suppression of depletion-induced apoptosis. BA/F-wild, -544, -517, -Fall, -Δbox1, and -Δbox2 were cultured in hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) or mIL-3 (1 ng/ml) containing medium or depleted medium for 24 h, and then DNA fragmentation (A) and caspase-3 like enzyme activity (B) were examined. In B, enzyme activities of factor-depleted sample (□), hGM-CSF supplied medium (▧) and mIL-3 supplied medium (█) are shown. Values are relative to those for the depleted sample. Experiments were repeated four times, and representative results of one experiment are presented.

The interleukin-1β-converting enzyme/CED-3 family of cysteine proteases, now renamed caspases (Alnemri et al., 1996), play key roles in apoptosis (Salvesen and Dixit, 1997). To examine whether factor depletion augments the enzymatic activation of caspases in BA/F3 cells, we analyzed caspase-1-like (Thornberry et al., 1992) and caspase-3-like (Kumar et al., 1994) enzyme activities through cleavage of fluorigenic peptide substrates specific for these enzymes using a spectrofluorophotometer. When we used the caspase-3-specific substrate Ac-DEVD-MCA, the augmentation of enzymatic activity was observed 5 h after factor depletion, and the activity continuously increased for up to 24 h after depletion. In contrast, when we used Ac-YVAD-MCA, a caspase-1 specific substrate (Thornberry et al., 1992), no enzymatic activation was detected (our unpublished results). We confirmed these results using other enzyme substrates, MocAc-YVADA PK(Dnp)-NH2 and MocAc-DEVDA PK(Dnp)-NH2 (Enari et al., 1996), and obtained essentially the same results (our unpublished results). We next analyzed the potential of hGM-CSF mutant receptors to suppress caspase-3-like enzyme augmentation, and again Fall, 544 and Δbox2 but not Δbox1 were capable of suppressing caspase-3 like enzyme activation (Figure 1B). Because neither mutant 544 nor Fall activates the MAPK cascade (Watanabe et al., 1993b; Itoh et al., 1998), activation of the MAPK cascade may not be required to prevent DNA fragmentation as well as the caspase-3-like enzyme activation induced by factor depletion.

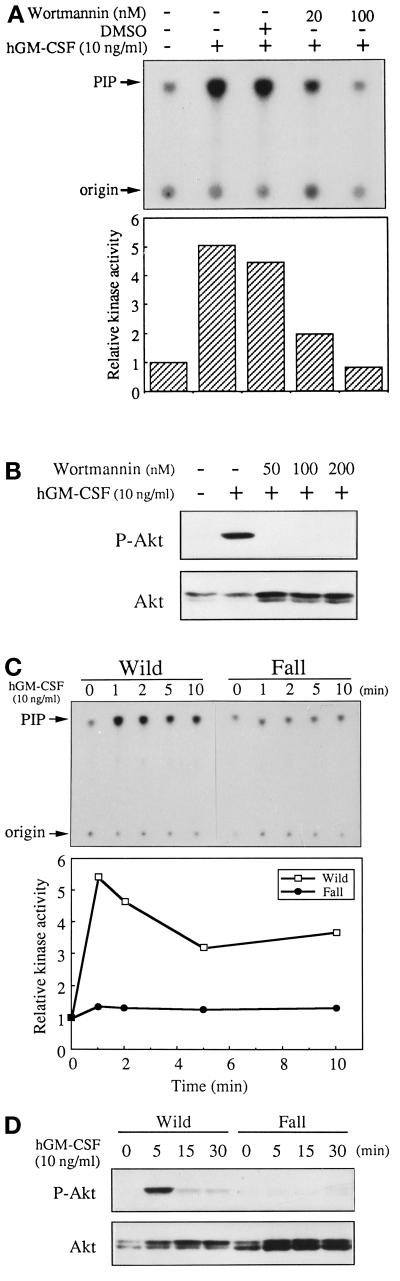

Activation of PI3-K and Akt by hGM-CSF in BA/F3 Cells

Because the role of PI3-K and Akt in cell survival is often discussed, we next asked whether this pathway is involved in hGM-CSF-dependent antiapoptosis activity. First, we examined the activation of both kinases by kinase assay for PI3-K and Western blotting for Akt using anti-phospho-Akt antibody. BA/F-wild cells were depleted of mIL-3 for 5 h and stimulated with hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml), and then immunoprecipitation using an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody was done. The immunoprecipitates obtained by anti-phosphotyrosine antibody were subjected to kinase assay of PI3-K using phosphatidylinositol as a substrate, and products of the kinase reaction were separated by TLC. Figure 2A shows activation of PI3-K when hGM-CSF was added to BA/F-wild cells. When we added wortmannin, a PI3-K inhibitor, this activation was completely abrogated as expected. Akt phosphorylation was then examined by Western blotting of total cell lysates. Cells were depleted of mIL-3 for 5 h and stimulated for 10 min by hGM-CSF, and Western blotting using an anti-phospho-Akt antibody was done using total cell lysates. As shown in Figure 2B, Akt phosphorylation was induced by additing hGM-CSF to BA/F-wild cells, and this activity was inhibited by the presence of wortmannin, indicating that Akt functions downstream of PI3-K in GM-CSF signaling. We next examined the activation of PI3-K and Akt through the hGMR Fall mutant. As shown in Figure 2, C and D, both PI3-K and Akt were not activated in BA/F-Fall cells by stimulation of hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml). Because Fall can suppress depletion-induced apoptosis, it can be speculated that Fall uses signaling pathways other than the PI3-K, Akt pathway for antiapoptosis activity.

Figure 2.

Activation of PI3-K and Akt by hGM-CSF in BA/F-wild cells. Activation of PI3-K and Akt in BA/F-wild in the presence or absence of wortmannin (A and B) or in BA/F-wild and BA/F-Fall cells (C and D) is shown. BA/F-wild cells were depleted of mIL-3 for 5 h and restimulated with hGM-CSF for 5 min. For PI3-K assay, immunoprecipitation was done using anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (4G10), and immunoprecipitates were subjected to kinase assay using phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylserine as substrates in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Products were separated by TLC plates. Arrows indicate applied origin and kinase reaction product phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP). The bar graph under the TLC pattern indicates the radioactivity intensity of products calculated by image analyzer (Fuji BAS-2000). Akt activity was analyzed by Western blotting of total cell lysates using anti-phospho-Akt antibody. The upper panel is the blotting pattern of anti phospho-Akt antibody, and the lower panel is the reblotting pattern of the same filter using anti Akt antibody.

Effects of Various Inhibitors on hGM-CSF-dependent Signaling Events, Survival, Proliferation, and Antiapoptosis in BA/F3 Cells

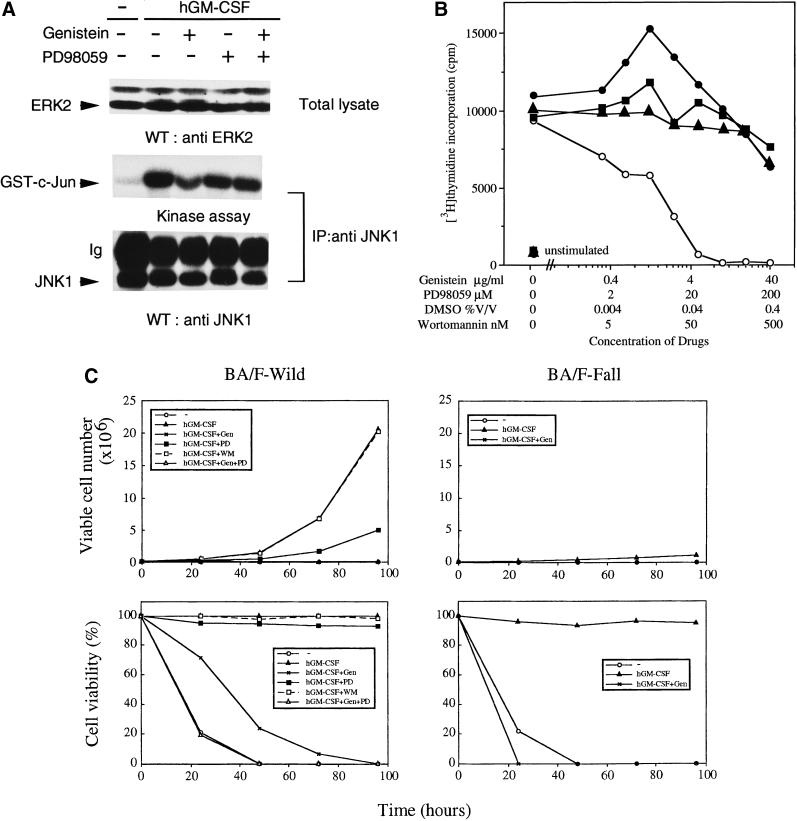

We reported that there are at least two distinct signaling pathways of the hGMR, one for the activation of the c-myc gene and cell proliferation and the other for activation of the c-fos gene (Watanabe et al., 1993b). The tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein inhibits GM-CSF-induced c-myc transcription and proliferation but does not affect the MAPK cascade (Watanabe et al., 1993b), suggesting that this tyrosine kinase inhibitor is an appropriate tool for examining these two signaling pathways. GM-CSF activates ERK and JNK through the same βc tyrosine residues (Liu et al., 1997a; Itoh et al., 1998). MEK1 is an upstream activator of ERK but not of JNK, and PD98059 is an MEK1-specific inhibitor (Alessi et al., 1995). We first examined the effect of the inhibitors on ERK2 and JNK1 activation by hGM-CSF. ERK2 activation was monitored by mobility shift in gel electrophoresis (Itoh et al., 1998), and a kinase assay was done for JNK1, using recombinant GST-c-Jun protein as a substrate (Liu et al., 1997a). PD98059 suppressed the mobility shift of ERK2 but did not affect JNK1 kinase activity (Figure 3A), suggesting that MEK1 is located upstream of ERK2 but not of JNK1 in hGM-CSF signaling. The addition of genistein did not affect the activation of either ERK or JNK1.

Figure 3.

Effects of genistein and PD98059 on hGM-CSF-dependent signaling events, proliferation, and viability. (A) Activation of ERK2 and JNK1 through hGM-CSF wild-type receptor in BA/F3 cells in the presence of either genistein or PD98059 or both was analyzed by Western blotting (ERK2) or kinase assay (JNK1), as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The Western blot pattern of JNK1 is shown to indicate the amount of immunoprecipitated JNK1. (B) Effects of PD98059 (●), genistein (○), wortmannin (▴), or DMSO as a control (▪) on [3H]thymidine incorporation induced by hGM-CSF. BA/F-wild cells (1.2 × 104 per well) were seeded in a 96-well plate in the presence of various doses of the indicated inhibitors and cultured for 24 h and then for an additional 4 h in the presence of [3H]thymidine. (C) Long-term proliferation and cell viability of BA/F-wild and -Fall cells in the presence of genistein (10 μg/ml), PD98059 (100 μM), or wortmannin. Viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion assay, and every 2 d cells were split and transferred to fresh media containing drugs.

We next analyzed effects of wortmannin in addition to the PD98059 and genistein on cell proliferation and viability. To test the effect of these inhibitors on cell proliferation, we examined [3H]thymidine incorporation of BA/F-wild cells. The addition of genistein completely suppressed [3H]thymidine incorporation, whereas the addition of a low dose of PD98059 enhanced this activity, and a higher dose slightly suppressed the proliferation (Figure 3B). Taken together, these results are consistent with our previous findings that the genistein-sensitive signaling pathway but not the MAPK pathway is essential for the cell proliferation induced by hGM-CSF in BA/F3 cells (Watanabe et al., 1993b). We also checked effects of wortmannin on [3H]thymidine incorporation. Wortmannin up to 250 nM was without effect.

hGM-CSF-dependent long-term proliferation and viability of BA/F-wild and -Fall cells in the presence of the inhibitors were examined by trypan blue exclusion assay. Addition of genistein suppressed long-term proliferation in BA/F-wild cell in response to hGM-CSF (Watanabe et al., 1993b), and the addition of PD98059 partially suppressed this long-term proliferation (Figure 3C, upper left panel). The addition of wortmannin had no effect on long-term proliferation. Numbers of BA/F-Fall cells increased slowly and this activity was suppressed in the presence of genistein (Figure 3C, upper right panel). When we examined the viability of BA/F-wild cells, addition of either genistein or PD98059 decreased cell viability in 20% of the cells, and most of cells were not viable after 5 d of culture, even in the presence of hGM-CSF (Figure 3C, lower left panel). When we added both genistein and PD98059, numbers of dead cells were the same as observed without hGM-CSF. In contrast to the partial effect of genistein for BA/F-wild cells, genistein abolished the hGM-CSF-dependent viability of BA/F-Fall cells. Because genistein has different effects on cell proliferation and cell survival, we examined effects of these inhibitors on the antiapoptosis activity of hGM-CSF.

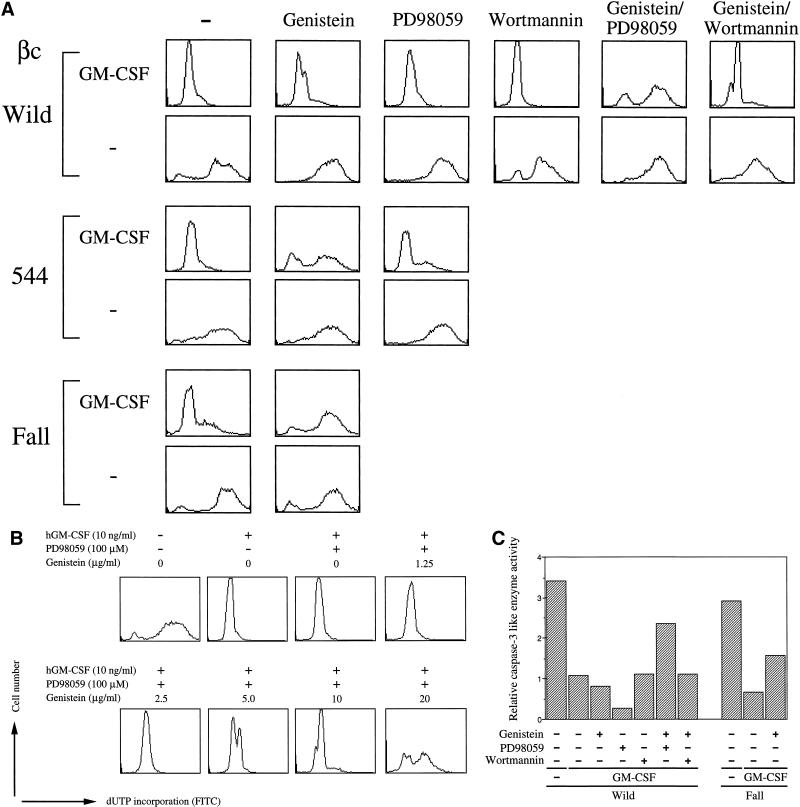

hGM-CSF-dependent Antiapoptosis in the Presence of Various Inhibitors

We first analyzed effects of inhibitors on DNA fragmentation by TUNEL analysis. As shown in Figure 4A, neither PD98059 nor genistein inhibited the anti-DNA fragmentation activity of hGM-CSF in BA/F-wild cells. Interestingly, when both genistein and PD98059 were present, hGM-CSF did not sustain this activity. And this effect of genistein appeared genistein dose dependent (Figure 4B). These results suggest that the activation of either one of these pathways is sufficient for antiapoptosis. In other words, neither pathway is essential for antiapoptotic activity through the wild-type hGM-CSF receptor. We next did similar experiments using mutant receptors, 544 and Fall, which cannot activate the MAPK cascade (Watanabe et al., 1993b). In these cells, the presence of genistein completely suppressed hGM-CSF-dependent anti-DNA fragmentation activity. On the other hand, the addition of PD98059 was without effect. Therefore, the genistein-sensitive signaling pathway appears to be sufficient to transduce viable signals induced by hGM-CSF in the mutant receptors 544 and Fall. Our observations are consistent with the conclusion obtained using BA/F-wild cells that the activity of either one of these pathways is sufficient for hGM-CSF-dependent antiapoptosis. Wortmannin did not affect hGM-CSF-dependent antiapoptotic activity even in the presence of genistein, findings that indicate that the PI3-K–Akt pathway does not play an essential role in hGM-CSF-dependent antiapoptosis. We confirmed these effects of inhibitors using other assay methods (Figure 4, C and D). Caspase-3 activity of BA/F-wild and -Fall cells was analyzed after 24-h culture of cells in the presence of inhibitors. Suppression of the caspase-3-like enzyme activity by hGM-CSF was partially but significantly inhibited in the presence of both PD98059 and genistein in BA/F-wild cells. In addition, PD98059, genistein, or wortmannin alone did not affect caspase-3-like enzyme activity. In contrast, addition of genistein partially abolished suppression of caspase-3 activation by hGM-CSF in BA/F-Fall cells.

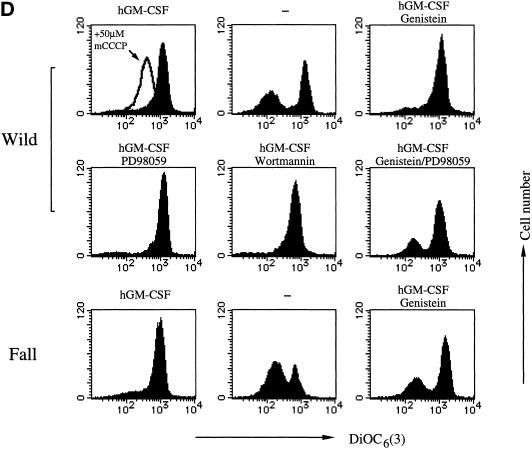

Figure 4.

Effects of drugs on hGM-CSF-dependent prevention of depletion induced apoptosis in BA/F3 cells. (A, C, and D) Effects of drugs on DNA fragmentation (A), caspase-3 activity (C), or mitochondria membrane potential (D) were examined. BA/F-wild (A, C, and D), -544 (A), and -Fall (A, C, and D) cells were depleted of mIL-3 and then treated with the indicated drugs. Cells were cultured 24 h, and DNA fragmentation, caspase-3 activity, or mitochondria membrane potential was examined by TUNEL analysis, enzyme assay using fluorescence-conjugated peptide substrate, by using DiOC6(3) as a membrane potential indicator, as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (B) Effect of various doses of genistein for anti-DNA fragmentation of hGM-CSF in the presence of PD98059. BA/F-wild cells were treated with various concentrations of genistein in the presence of PD98059 (100 μM) 15 min before stimulation by hGM-CSF, and DNA fragmentation was analyzed by TUNEL analysis after 24 h of culture.

Mitochondria membrane potential of BA/F-wild and -Fall cells in the presence of inhibitors was analyzed by using DiOC6(3) as a membrane potential indicator. Cells were cultured in the indicated medium for 16 h, and membrane potential was analyzed. Addition of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone, which is known to abolish membrane potential, to the BA/F-wild cells cultured in the presence of hGM-CSF indicates that the DiOC6(3) staining of BA/F-wild cells was driven by Δψm (Figure 4D, upper left panel). When we added various combinations of inhibitors, collapses of Δψm happened in BA/F-wild cells only when both genistein and PD98059 were present. Addition of genistein abolished Δψm of BA/F-Fall cells. These findings are consistent with those obtained by TUNEL analysis.

Effects of Inhibitors on hGM-CSF-dependent Gene Induction

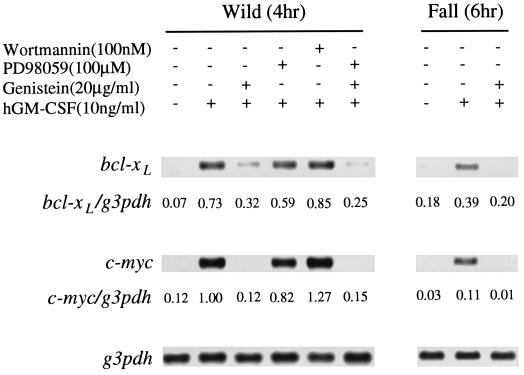

The c-Myc or Bcl-2 family proteins have been implicated to be involved in antiapoptosis in several types of cells (Leverrier et al., 1997). We next examined the induction of mRNA encoding these proteins by wild-type and Fall hGMR, using Northern blotting analysis of bcl-2, bcl-xL, and c-myc. With the bcl-2 probe, we observed only weak signals (our unpublished results) and hence could not examine the inducibility. Figure 5 shows Northern blotting patterns probed with c-myc or bcl-xL cDNA. The cells were depleted of factor for 5 h and restimulated with hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) for 4 h for c-myc as well as for bcl-xL mRNA analyses. In both cases, wild-type hGMR is capable of inducing these genes through hGM-CSF stimulation, but activation of only c-myc was evident in BA/F-Fall cells. A longer stimulation resulted in the clear induction of bcl-xL in BA/F-Fall, which suggested that kinetics of bcl-xL activation is slower than observed in BA/F-wild cells. We next examined effects of the inhibitors on the induction of c-myc and bcl-xL gene. In contrast to the complete inhibition of c-myc gene induction by genistein, induction of the bcl-xL gene was only partially suppressed. The addition of PD98059 affected neither c-myc nor bcl-xL induction, suggesting that the MEK1 pathway may not be essential for activation of these genes. When we added both PD98059 and genistein, the level of suppression was the same as that observed in the presence of genistein only. Interestingly, when we added both inhibitors, bcl-xL induction was partially suppressed but still remained significantly. These results suggested that the regulatory mechanisms of c-myc and bcl-xL gene induction were clearly different, although involvement of both genes in antiapoptosis was suggested.

Figure 5.

Analysis of c-myc and bcl-xL gene induction by hGM-CSF through wild-type or Fall. The induction of c-myc and bcl-xL gene expression was analyzed by Northern blot analysis. BA/F-wild and -Fall (for c-myc and bcl-xL) were depleted of factor for 5 h and restimulated with hGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) for 4 h (BA/F-wild cells), or 6 h (BA/F-Fall cells) in the presence or absence of the inhibitors. mRNA was then extracted, and Northern blotting was done. Control blotting was done using G3PDH as a probe.

DISCUSSION

Using various hGMR βc mutants, we found that deletion of only the box1 region of βc caused apoptosis, thus demonstrating its importance. Among the various mutants of βc, Fall can sustain survival with impaired promotion of proliferation (Okuda et al., 1997; Itoh et al., 1998). Fall maintains the ability to fully activate JAK2 but is not capable of activating STAT5 or the MAPK cascade (Itoh et al., 1998), thereby indicating a role for JAK2 in the antiapoptosis activity of GM-CSF. Consistent with these observations, mutation analysis of the erythropoietin receptor showed that activation of JAK2 is necessary and sufficient for suppression of γ irradiation-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by erythropoietin (Quelle et al., 1998). We also found that a chimeric molecule consisting of βc extracellular and transmembrane regions fused with whole JAK2 sustains cell survival of BA/F3 cells (Liu et al., 1999). Furthermore, fusion of the kinase domain of JAK2 and the extracellular domain of CD16 showed that artificial activation of JAK2 rescues BA/F3 cells from apoptosis (Sakai and Kraft, 1997).

The finding that mutant Fall, which lacks MAPK activation, can sustain the survival of BA/F3 cells is interpreted to mean that activation of STAT5 or MAPK pathways has no essential role in the antiapoptosis activity of βc. The involvement of R-ras, perhaps upstream of the MAPK cascade in this activity, was suggested by other studies. For example, constitutive active R-ras prevents DNA fragmentation induced by factor depletion, but dominant negative R-ras failed to block the anti-DNA fragmentation activity of IL-3 in BA/F3 cells (Terada et al., 1995). Similar results were observed with another mIL-3-dependent cell line, 32D. In this case, expression of the dominant negative R-ras suppressed IL-3-induced proliferation but did not affect cell viability (Okuda et al., 1994). These observations indicate that activation of the R-ras pathway by GM-CSF is dispensable for the antiapoptosis activity of GM-CSF, whereas forced activation of this pathway can rescue cells from apoptosis. This notion is consistent with our present data that activation of the MAPK pathway by GM-CSF is essential for antiapoptosis only when the genistein-sensitive pathway is impaired. We examined whether activation of MEK1 is enough for antiapoptosis by transient transfection of constitutively active MEK1 (S218/222E). The obtained results showed a slight but insignificant effect of the constitutively active MEK1 on anti–depletion-induced apoptosis in BA/F3 cells (Izawa, Liu, and Watanabe, unpublished results), indicating the possible requirement of an unknown signal directly from JAK2 in addition to the MEK1 pathway.

We reported that JNK is activated by GM-CSF (Liu et al., 1997a), and this activation depends on the middle three tyrosines of βc, which are also required for MAPK cascade activation (Itoh et al., 1998). The observation that PD98059 suppressed hGM-CSF-induced ERK2 but not JNK activation suggested that the activities of ERK and JNK may be modified differently in the presence of PD98059. Because the role of JNK activation in apoptosis was reported as being both positive and negative (Su et al., 1994; Xia et al., 1995; Lenczowski et al., 1997), further analysis is required to determine how PD98059 differentially affects antiapoptosis through JNK and ERK activation.

PI3-K is assumed to be one target of R-ras, because direct interaction between the GTP form of R-ras and PI3-K was reported (Rodriguez-Viciana et al., 1994). The requirement of PI-3K for prevention of apoptosis was first noted in signals of nerve growth factor in pheochromocytoma PC-12 cells, using PI3-K inhibitors wortmannin (Ui et al., 1995) and LY294002 (Vlahos et al., 1994; Yao and Cooper, 1995). Our results indicate that PI3-K activation is not the main pathway of hGM-CSF antiapoptotic activity in BA/F3 cells. We obtained essentially the same results using LY294002 (our unpublished results). Interestingly, a previous report using wortmannin and LY294002 showed that these inhibitors affected IL-3-dependent cell viability to a greater extent than did GM-CSF (Scheid et al., 1995).

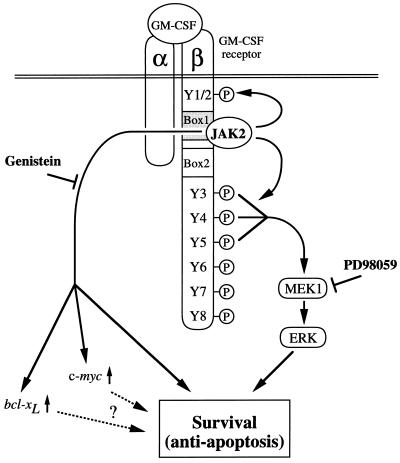

Using βc C-terminal deletion mutants, the region between amino acids 544 and 763 was found to be essential for antiapoptosis activity (Kinoshita et al., 1995). Because the region for antiapoptosis defined by that report stretched over nearly 220 of the 430 amino acids in the βc cytoplasmic region, we reevaluated the requirement of βc regions for various GM-CSF activities, including antiapoptosis, MAPK cascade activation, and proliferation. We first noted that the 46 amino acids located between amino acids 544 and 589 are critical and sufficient for c-fos activation (Itoh et al., 1996). Then, by constructing the Y series, we obtained various mutants such as Y12, Y6, Y7, and Y8, which can activate proliferation without activation of the MAPK cascade and c-fos activation (Itoh et al., 1998). In the present work, further analyses using various βc mutants including C-terminal deletions and Y series mutants revealed that BA/F3 cells survive through mutants 544, Y12, Y6, Y7, and Y8, all of which lack the region or tyrosine residues required for MAPK cascade activation. Therefore, our results are consistent for all the mutants. It should be emphasized that JAK2 activation through the box1 region is required for both the genistein-sensitive pathway, which can be transduced independently of the βc tyrosines, and the MEK1/ERK pathway, which depends on the βc tyrosines. Thus, the deletion of box1 results in the blockade of both of these downstream pathways, leading to the induction of apoptosis (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of signaling pathways of hGM-CSF receptor for antiapoptosis

Based on these results, we can classify βc mutants into three groups: the first group activates proliferation, survival, and the MAPK cascade leading to c-fos activation; the second group activates proliferation as well as survival but not the MAPK cascade; and the third is Fall, which has activity to promote cell survival but not proliferation. Our finding that Fall can activate c-myc and bcl-xL genes implies that these genes are potentially involved in cell survival but may not play a role to the extent for proliferation. Revealing the differences in signaling events between Fall and the second group of mutants may shed light on the nature of signals that promote cell proliferation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kayo Hagino, Kumiko Nakada, Yukitaka Izawa, and Yutaka Aoki for excellent technical support, Drs. Shinobu Imajo-Ohmi and Marty Dahl for helpful discussion, and Mariko Ohara for comments.

REFERENCES

- Alessi DR, Guenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT, Saltiel AR. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnemri ES, Livingston DJ, Nicholson DW, Salvesen G, Thornberry NA, Wong WW, Yuan J. Human ICE/CED-3 protease nomenclature. Cell. 1996;87:171. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K, Lee F, Miyajima A, Miyatake S, Arai N, Yokota T. Cytokines: coordinators of immune and inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:783–836. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise LH, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nunez G, Thompson CB. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzi MF, Zini MG, Aronica MG, Blechman JM, Yarden Y, Pegoraro L. Convergence of signaling by interleukin-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and mast cell growth factor on JAK2 tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31680–31684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Takeyama N, Brady G, Watson AJM, Dive C. Blood cells with reduced mitochondrial membrane potential and cytosolic cytochrome C can survive and maintain clonogenicity given appropriate signals to suppress apoptosis. Blood. 1998;92:4545–4553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MKL, Marvel J, Malde P, Lopez-Rivas A. Interleukin 3 protects murine bone marrow cells from apoptosis induced by DNA damaging agents. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1043–1051. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Peso L, Bonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enari M, Talanian RV, Wong WW, Nagata S. Sequential activation of ICE-like and CPP32-like proteases during Fas-mediated apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380:723–726. doi: 10.1038/380723a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Sarabia MJ, Bischoff JR. Bcl-2 associates with the ras-related protein R-ras p23. Nature. 1993;366:274–275. doi: 10.1038/366274a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Cantley LC. A bad kinase makes good. Nature. 1997;390:116–117. doi: 10.1038/36442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyca W, Gong J, Darzynkiewics A. Detection of DNA strand breaks in individual apoptotic cells by the in situ terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and nick translation assays. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1945–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashida K, Kitamura T, Gorman DM, Arai K, Yokota T, Miyajima A. Molecular cloning of a second subunit of the human GM-CSF receptor: reconstitution of a high affinity GM-CSF receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9655–9659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry D, Nunez G, Milliman C, Schreiber R, Korsmeyer S. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Liu R, Yokota T, Arai K, Watanabe S. Definition of the role of tyrosine residues of the common β subunit regulating multiple signaling pathways of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:742–752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Muto A, Watanabe S, Miyajima A, Yokota T, Arai K. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor provokes Ras activation and transcription of c-fos through different modes of signaling. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7587–7592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Yokota T, Arai K, Miyajima A. Suppression of apoptotic death in hematopoietic cells by signalig through the IL-3/GM-CSF receptors. EMBO J. 1995;14:266–275. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Induction of apoptosis by the mouse nedd2 gene, which encodes a protein similar to the product of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell death gene ced-3 and the mammalian IL-1β-converting enzyme. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1613–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenczowski JM, Dominguez L, Eder A, King LB, Zacharchuk CM, Ashwell JD. Lack of a role for Jun kinase and AP-1 in Fas-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:170–181. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverrier Y, Thomas J, Perkins GR, Mangeney M, Collins M, Marvel J. In bone marrow derived Baf-3 cells, inhibition of apoptosis by IL-3 is mediated by two independent pathways. Oncogene. 1997;14:425–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CB, Itoh T, Arai K, Watanabe S. Constitutive activation of JAK2 confers murine interleukin-3-independent survival and proliferation of BA/F3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6342–6349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Itoh T, Arai K, Watanabe S. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) by human granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (hGM-CSF) in BA/F3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997a;234:611–615. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Itoh T, Arai K, Watanabe S. Differential requirement of tyrosine residues from distinct signaling pathways of GM-CSFR. FASEB J. 1997b;11:A923. [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima A, Mui AL-F, Ogorochi T, Sakamaki K. Receptors for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3, and interleukin-5. Blood. 1993;82:1960–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima A, Schreurs J, Otsu K, Kondo A, Arai K, Maeda S. Use of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, and an insect baculovirus vector for high-level expression and secretion of biologically active mouse interleukin-3. Gene. 1987;58:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda K, Ernst TJ, Griffin JD. Inhibition of p21ras activation blocks proliferation but not differentiation of interleukin-3-dependent myeloid cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24602–24607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda K, Smith L, Griffin JD, Foster R. Signaling functions of the tyrosine residues in the βc chain of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor. Blood. 1997;90:4759–4766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios R, Steinmetz M. IL-3-dependent mouse clones that express B-220 surface antigen, contain lg genes in germ-line configuration, and generate B lymphocytes in vivo. Cell. 1985;41:727–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelle FW, Sato N, Witthuhn BA, Inhorn RC, Eder M, Miyajima A, Griffin J, Ihle JN. JAK2 associates with the βc chain of the receptor for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and its activation requires the membrane-proximal region. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4335–4341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quelle FW, Wang J-L, Feng J, Wang D, Cleveland JL, Ihle JN, Zambetti GP. Cytokine rescue of p53-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest is mediated by distinct Jak kinase signaling pathways. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1099–1107. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne PH, Dhand R, Vanhaesebroeck B, Gout I, Fry MJ, Waterfield MD, Downward J. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase as a direct target of ras. Nature. 1994;370:527–532. doi: 10.1038/370527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai I, Kraft AA. The kinase domain of Jak2 mediates induction of Bcl-2 and delays cell death in hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12350–12358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamaki K, Miyajima I, Kitamura T, Miyajima A. Critical cytoplasmic domains of the common β subunit of the human GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 receptors for growth signal transduction and tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1992;11:3541–3550. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Caspases: intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid MP, Lauener RW, Duronio V. Role of phos-phatidylinositol 3-OH-kinase activity in the inhibition of apoptosis in hemopoietic cells: phosphatidylinositol 3-OH-kinase inhibitors reveal a difference in signaling between interleukin-3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor. Biochem J. 1995;312:159–162. doi: 10.1042/bj3120159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su B, Jacinto E, Hibi M, Kallunki T, Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. JNK is involved in signal integration during costimulation of T lymphocytes. Cell. 1994;77:727–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Kaziro Y, Koide H. An activated mutant of R-Ras inhibits cell death caused by cytokine deprivation in BaF3 cells in the presence of IGF-1. Oncogene. 1997;15:1689–1697. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada K, Kaziro Y, Satoh T. Ras is not required for the interleukin 3-induced proliferation of a mouse proB cell line, BaF3. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27880–27886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry NA, et al. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin1-β processing in monocytes. Nature. 1992;1992:768–774. doi: 10.1038/356768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui M, Okada T, Hazeki K, Hazeki O. Wortmannin as a unique probe for an intracellular signaling protein, phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Trends Biol Sci. 1995;20:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux DL, Cory S, Adams JM. Bcl-2 gene promotes hemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize preB cells. Nature. 1988;335:440–442. doi: 10.1038/335440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Ishida S, Koike K, Arai K. Characterization of cis-regulatory elements of the c-myc promoter responding to human GM-CSF or mouse interleukin 3 in mouse proB cell line BA/F3 cells expressing the human GM-CSF receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 1995a;6:627–636. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.6.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Itoh T, Arai K. JAK2 is essential for activation of c-fos and c-myc promoters and cell proliferation through the human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor in BA/F3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12681–12686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Ito Y, Miyajima A, Arai K. Granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor dependent replication of Polyoma virus replicon in hematopoietic cells: analyses of receptor signals for replication and transcription. J Biol Chem. 1995b;270:9615–9621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Mui AL-F, Muto A, Chen JX, Hayashida K, Miyajima A, Arai K. Reconstituted human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor transduces growth-promoting signals in mouse NIH 3T3 cells: comparison with signaling in BA/F3 proB cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993a;13:1440–1448. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Muto A, Yokota T, Miyajima A, Arai K. Differential regulation of early response genes and cell proliferation through the human granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor: selective activation of the c-fos promoter by genistein. Mol Biol Cell. 1993b;4:983–992. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.10.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G, Smith C, Spooncer E, Dexter T, Taylor D. Hemopoietic colony stimulating factors promote cell survival by suppressing apoptosis. Nature. 1990;343:76–79. doi: 10.1038/343076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R, Cooper GM. Requirement of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in the prevention of apoptosis by nerve growth factor. Science. 1995;267:2003–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.7701324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami N, Marchetti P, Castedo M, Zanin C, Vayssiere J-L, Petit PX, Kroemer G. Reduction in mitochondrial potential constitutes and early irreversible step of programmed lymphocyte death in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1661–1672. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14–3-3 not Bcl-xL. Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]