SYNOPSIS

After fall 2001, scientists and professionals recognized the importance of integrating public health with traditional first-response professions in planning and training for disasters. However, operationalizing this approach among professionals in the field confronted barriers that were both inter-cultural and jurisdictional. The Pennsylvania Preparedness Leadership Institute (PPLI) is a collaboration of the Pennsylvania Department of Health and the University of Pittsburgh Center for Public Health Preparedness. Team members are recruited from public health, emergency medicine, emergency management, hospitals, and public safety agencies from each of nine multi-county regions in Pennsylvania. Each team takes on a year-long project that addresses a strategic problem as a focus for capacity-building within its region. Unexpectedly during PPLI's first year in operation, a hepatitis-A outbreak tested whether one regional team could successfully mount the necessary integrated response. This experience, as well as the planned evaluation for PPLI, demonstrated both the successful processes and the positive impact of this integrated leadership training initiative.

Prior to September 2001, a number of federal programs had focused on emergency preparedness, most significantly through the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici amendment to the Defense Authorization Act in fiscal year 1997 (Public Law 104-201).1 However, the focus of these programs had been on chemical, nuclear, and radiological agents.1,2 The participating agencies in the then-prevailing efforts were first-responders (i.e., emergency medical services, fire, police, and hazardous-materials teams). But the anthrax threats of October 2001 emphasized the need to take a more comprehensive view of preparedness—one that includes biological agents. This expanded approach required the inclusion of public health. Post-2001 planning, as well as training to carry out the plans, has taken an “all-hazards” approach that seeks to incorporate public health functions targeted to the detection and containment of biologic agents. Thus, the federal definition of first responders published in 2003 includes public health among the other agencies and professions “that provide immediate support services during prevention, response, and recovery operations.”3

However, integrating public health with the planning and training of traditional first-responders poses professional/cultural and jurisdictional barriers. Emergency-response training coordinated at the federal level does not fully address the varied functions of public health personnel.4 Further, the needs of disaster response often exceed both local resources and state-level response times, thus calling for regional contributions and cooperation. But public health authorities are organized under state laws that define different geographic boundaries and separate powers from those of emergency-management, emergency medical services, and public safety (i.e., police, firefighters). Finally, the variability of local conditions and resources often requires detailed inter-agency strategic planning, beyond the specifications of federal and state level plans for emergency management.

In response to the need for integrated training and planning for all-hazards at the local and regional levels, the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Office of Public Health Preparedness (PA-DOH) and the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Public Health Preparedness (UPCPHP) collaborated to develop and implement the Pennsylvania Preparedness Leadership Institute (PPLI). This article describes the institute, including its objectives, curriculum, and evaluation results. The first-year evaluation includes participant satisfaction, process results of their team projects, and a limited field-test of performance. This preparedness leadership model may be useful to other states and other academic preparedness centers.

PENNSYLVANIA PREPAREDNESS LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE

Background

PPLI was conceived through a convergence of opportunities that arose in Pennsylvania in early 2002. These opportunities included an interdisciplinary regional structure for preparedness activities, an established venue and academic-practice partnerships for public health training, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funding for leadership development and preparedness training funneled to both the health department and the school of public health.

Regional preparedness structure.

Historically, Pennsylvania's organization of emergency management functions reflects the maxim that “all disasters are local.” In each county, an emergency coordinator is appointed by elected officials, typically a board of commissioners. The coordinator's role is to organize, plan, train, and execute the county's response to disasters and emergencies among its police, fire, hazardous materials, and emergency medical services. The county coordinator calls upon the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA) for funds, personnel, and equipment when the scope of a disaster warrants. Nevertheless, disasters requiring rapid response often exceed an individual county's resources, so adjoining counties have self-selected to create voluntary associations and mutual-aid agreements.

The events of September 11, 2001, spurred the Pennsylvania General Assembly to enact a statute (Act 227 of 2002, “Counter-Terrorism Planning, Preparedness and Response Act”) that legitimized these existing informal multi-county regions. The statutory plan formally divides the commonwealth into nine multi-county regions called Regional Counter-Terrorism Task Forces (RCTTFs), each chaired by one of its county emergency coordinators. Though each coordinator remains formally accountable to the elected officials in his county, the RCTTFs as multi-county units are the recipients of both funding and guidance from PEMA. Thus, Pennsylvania was among the first states in the nation to develop a multi-county structure for counter-terrorism planning, training, and response.

Statewide training venues.

Starting in the late 1990s, the PA-DOH and the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Public Health Practice began to build a partnership to support public health training, which later became the foundation for the preparedness leadership training. In Spring 1999, PA-DOH convened an advisory group of health professionals and academics to assist with start-up of its new Public Health Institute. Intended to provide an in-person learning venue for all public health topics with minimal travel time for trainees, the Public Health Institute would offer a week-long program of courses. With the PA-DOH jurisdiction divided into six multi-county districts, the Public Health Institute location would be geographically moved to a different district twice each year and from year to year.

At about this same time, the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Public Health Practice received the first of several federal grants to conduct off-site training for public health professionals. Thus, the center's representative contributed as a member of the Public Health Institute's advisory group, and courses taught by the center's faculty were offered within the institute's curriculum. Sessions of the Public Health Institute commenced with regular events each fall and each spring beginning in October 1999 and are continuing to the present.

Leadership development funding.

Given the previous development of regional RCTTFs and a statewide Public Health Institute, Pennsylvania was well positioned to create an integrated leadership development program when, in spring 2002, CDC provided the necessary funding. At that time, PA-DOH and all other state health departments received guidance from the CDC to apply for supplemental funds for preparedness, including criteria for planning and leadership (Focus Area A). Simultaneously, the CDC funded the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Public Health Preparedness (UPCPHP) whose leadership then consulted closely with the PA-DOH to develop programs to complement, enhance, and support the state's public-health preparedness efforts. Together, UPCPHP and PA-DOH recognized the need to integrate leadership development for public health professionals with training already established separately for the traditional first-responders at the county and regional levels.

Purpose, objectives, and partners

The purpose of the PPLI is to engage in the cross-cutting development of leaders to strengthen the response to bioterrorism, infectious disease, and other public health threats and emergencies. Its objectives are to:

Administer and coordinate an annual year-long program of leadership development for Pennsylvania's first-responders and public-health professionals;

Provide liaison with key stakeholders including RCTTFs, state and local health departments, emergency management officials, emergency services, hospitals, and public safety professionals;

Support the design and delivery of a leadership development curriculum; and

Recruit and develop an annual cohort of leadership scholars organized into regional teams with representation from the stakeholder groups.

Through their established partnership, the UPCPHP and the PA-DOH agreed to share personnel, funding, and their respective institutional strengths to plan, implement, and sustain PPLI. Notably, UPCPHP contributed the time of a director, a facilitator, and a team of outside consultants; PA-DOH contributed books and materials, logistical support, and its ongoing Public Health Institute as the venue for in-person leadership sessions. Both PA-DOH and UPCPHP worked on the convening of stakeholders and the development of curriculum. PPLI's teams of leadership scholars include professionals drawn from the nine RCTTFs, the six districts of the state health department, and the 10 local health departments serving an individual county or municipality within the state. Most members of PPLI's initial cohort of scholars came from Pennsylvania's rural counties, thus giving PPLI a strong rural focus. PPLI's organizers include the participation of the University of Pittsburgh's Center for Rural Health Practice (located at the regional campus in Bradford, McKean County, Pennsylvania).

The PPLI curriculum

Among the first of its kind, PPLI's curriculum incorporates model elements and components of leadership development,5 and it combines the subject matter of both adaptive leadership6 and emergency preparedness and response.7 The year-long program is strategically focused on intra-regional problem-solving through team projects, designed to strengthen emergency-response capacity within the RCCTF regions from which the scholar teams are drawn. PPLI recognized that scholars would be experienced and knowledgeable about the strategic strengths and weaknesses of preparedness within their own respective regions. Scholars would be charged with defining a regional preparedness problem and would spend the year working on it as a regional team. This approach would assure that PPLI's outcomes included not only enhanced leadership competency for individual participants, but also strategically improved and better integrated performance capacities for public health, emergency management, emergency medical service, hospital, and public safety organizations.

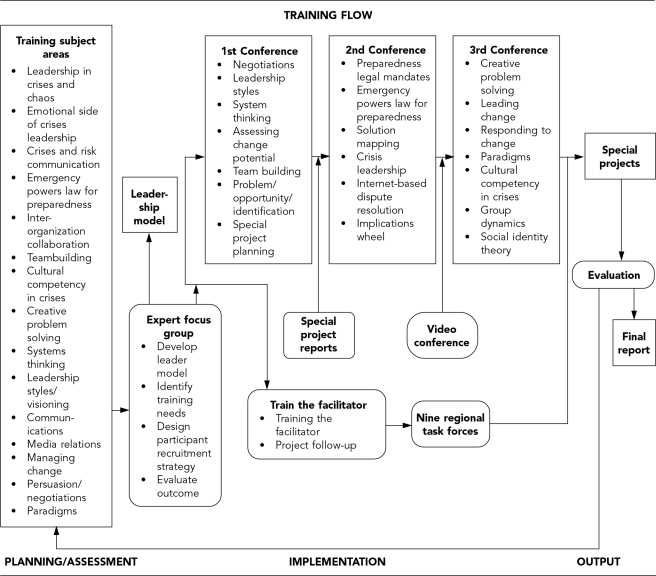

A training flow diagram for PPLI (Figure) shows the process from planning/assessment through implementation and outputs, including a final report on team projects.

Figure. Training flow chart for the PPLI's sequence of content-planning/content-assessment, implementation, and output evaluation.

PPLI = Pennsylvania Preparedness Leadership Institute

Planning/assessment phase.

PPLI's planning/assessment process identified training subject areas and a leadership model. The training subject areas include both adaptive leadership elements and topics specific to emergency preparedness. In the early development of the PPLI curriculum, we consulted with St. Louis University's Preparedness Center to review the leadership curriculum it had pilot-tested during the preceding year. As a result, that curriculum formed the foundation for PPLI's training subject areas. PPLI's stakeholders met in Pittsburgh in October 2002 to review these curriculum areas. The stakeholders developed the design for PPLI, helping both to identify training needs and to recommend recruitment strategies. The curriculum outlined at the meeting received continuous review, validation, and modification based on input by the year-one scholars and the stakeholders.

Implementation phase.

PPLI's implementation consists of three in-person conferences with interim work through special project reports and a video conference. The first conference begins the year-long program for scholar cohorts. It encompasses the topics of negotiations, leadership styles (using the Myers-Briggs tool), system thinking, team building, problem identification, and special project planning. These subject areas are presented at the first session to provide scholars the foundation they will need to better work within their counter-terrorism task forces and to organize their projects. The teams' special projects are discussed and chosen at this session.

The second conference, held approximately six months after the first, begins with facilitator training. This gives the scholars skills needed to hold meetings and to better plan and implement their projects. This session also includes issues relevant specifically to preparedness planning, such as a review of the Model Emergency Health Powers Act8 and other legal mandates,9 crisis leadership, and problem-solving techniques such as solution mapping and the implications wheel (both of which both also help in the development and implementation of the team projects).

The third in-person conference at the conclusion of the scholars' year includes the topics of creative problem solving, leading and responding to change, paradigm changes, cultural competency in crises, group dynamics, and social identity theory. During this session, the scholars present their projects to each other as well as to the next cohort of scholars, who by this time have been recruited and are meeting for their first conference.

Output.

The results of the scholars' team-project presentations contribute one of the three elements of PPLI's impact evaluation. At the October 2002 stakeholders meeting and afterward, discussions about how to evaluate the PPLI experience focused on the team projects. Since each team would tackle a regional issue or problem as its project, the products and results of the project would be an obvious way to measure the team's success. Additionally, the team project results constitute indicators of whether PPLI was achieving its overall mission to strengthen the state's planning and preparedness efforts at the regional level.

First-year experience and modifications

The first PPLI cohort of 28 scholars participated from June 2003 to May 2004; and the second cohort, selected during Spring 2004, met initially in May 2004.

It is important to note that all PPLI sessions for skill-building are not just presentations; rather, the goal is for scholars to leave the sessions knowing how to use specific techniques and skills to improve their work. For example, the year-one scholars needed a great deal of training to work effectively as teams. By nature, many of them are individuals in command positions, and yet, due to the regionalization of emergency management, had to learn to become team members and team builders. This was a cultural change around which they needed substantial skill-building.

Another feature is that PPLI's training subject areas are dynamic, changing in response to both stakeholders' and scholars' inputs. For example, the year-one scholars believed that they had already received sufficient training in incident command, so that topic was removed from the originally planned curriculum. Also, as scholars pursued their team projects, they realized the need for additional training in team-building, negotiation, and creative problem-solving, so time for those topics in the curriculum was increased.

EVALUATION OF PPLI, YEAR ONE

PPLI attracted its intended audience of leadership trainees by recruiting 28 professionals from eight of the nine RCTTF regions and from public health, public safety, emergency management, and emergency medical services. This result is probably attributable to the initial and ongoing involvement of stakeholders from each of these groups throughout the planning/assessment, implementation, and output phases of PPLI.

Evaluation of the PPLI has occurred through a combination of participant-satisfaction surveys for both presenter effectiveness and program content, process outcomes from the team projects, and an unanticipated opportunity to demonstrate the impact of the PPLI experience by one team of scholars.

Participant satisfaction

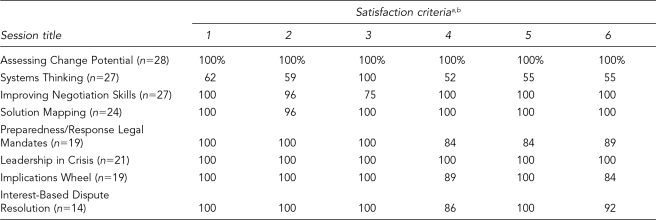

A total of eight sessions was offered during the first two conferences of year one. Scholars rated each session on six criteria measuring presenters and methods and on two additional criteria measuring program content.

Table 1 summarizes the percentage of scholars who gave favorable ratings for the presenters and for their methods in each of the sessions. The scholars were asked to select an answer to Questions 1 through 4 from a five-point scale (Absolutely Not, Probably Not, Uncertain, Somewhat, and Absolutely). They selected an answer to Questions 5 and 6 from a four-point scale (Poor, Fair, Good, or Excellent). On the whole, these ratings indicated a perception of high quality for the materials, presentations, instructors' responsiveness and value, and the sessions overall.

Table 1. Satisfaction with presenters and methods: percentage of participants giving favorable ratings.

aFor Criteria 1 through 4, “favorable” ratings were answer choices of either somewhat or absolutely (rather than uncertain, probably not, or absolutely not). For Criteria 5 and 6, “favorable” ratings were answer choices of either good or excellent (rather than fair or poor).

- Were the session materials written and organized clearly?

- Were the session content and presentations easy to follow?

- Was the instructor responsive to your questions or concerns?

- Would you participate in another session from this speaker?

- How would you rate the overall value of this speaker?

- How would you rate the overall value of this session?

For the Systems Thinking session, the scholars' ratings of presenters and methods were consistently lower than those for the other sessions. This session's presenter was relatively inexperienced, having been substituted for the scheduled presenter with short notice. One scholar commented, “I think the concept is good. I don't think the presentation fits well.” Even so, more than half of the scholars rated this session as “Somewhat” or “Absolutely” successful on all six presenter/methods criteria.

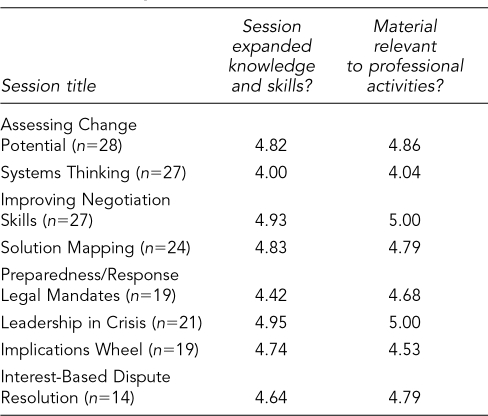

Table 2 shows the mean ratings of program content on two criteria: whether the session expanded knowledge and skills and whether the materials were relevant to the scholar's professional activities. The same five-point scale was used for these questions as for those in Table 1 (Absolutely Not, Probably Not, Uncertain, Somewhat, and Absolutely). The mean ratings on both criteria were very high: 4.67 for knowledge expansion and 4.71 for relevance. Again, the Systems Thinking session rated lower than the other sessions, but even so its ratings were relatively high: 4.00 for knowledge expansion and 4.04 for relevance.

Table 2. Participants' ratings of program content on five-point scalea.

aRatings: 1=absolutely not; 2=probably not; 3=uncertain; 4=somewhat; 5=absolutely

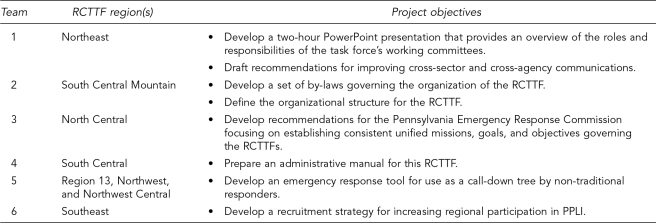

Process outcome of team projects

Table 3 lists the six team projects selected and defined by the year-one scholars. It was striking to the PPLI's sponsors that four of the projects focused on the lack of coordination, planning, and management within the RCTTF regions. In discussions during their second conference, the scholars argued that they needed state-level attention and guidance to address these issues within their regions and across all nine RCTTF regions in the commonwealth. Their recommendations led to two specific actions. First, the PPLI's sponsoring organizations, the PA-DOH and the UPCPHP, requested and attended a meeting with PEMA leadership to address the issue of statewide emergency planning and coordination. PEMA agreed to endorse the PPLI program and to participate in its curriculum. Second, as a direct result of that meeting, the curriculum for the year-one third conference was modified to include a panel presentation by leaders from PA-DOH, PEMA, and the Pennsylvania Office of Homeland Security during which their leaders would engage in dialogue directly with the year-one scholars.

Table 3. Team project objectives for year-one PPLI scholars.

RCTTF = Regional Counter-Terrorism Task Force

PPLI = Pennsylvania Preparedness Leadership Institute

Leadership response to hepatitis-A outbreak

Previous evaluation of leadership training highlighted the participants' enhanced professional networks, which is related to participants' self-rated professional effectiveness.10 The building of professional networks also occurred among PPLI's scholars and was noted as contributing to effectiveness during an actual infectious disease outbreak. Unexpectedly during the initial year of PPLI, an outbreak of hepatitis-A occurred. More than 600 cases were identified in Pennsylvania, and six cases appeared in other states, the largest outbreak of its kind ever recorded nationally.11 Scholars then participating in PPLI from the state's southwestern region were involved firsthand in the outbreak response. The response included a mass-immunization clinic based at the local community college, through which approximately 9,000 individuals with risk of exposure received immune globulin to prevent illness. Secondary infections were limited to six, and deaths were limited to three. PPLI was not in a position to evaluate the scope and dynamics of this outbreak response overall, which had been mounted by numerous agencies, organizations, and professionals at the local, state, and federal levels. However, one of the scholars who had been the public-health incident commander commented later that the response had been well managed, in part because members of the response team (including the regional public health, public safety, emergency medical, and hospital systems) had become acquainted with each other as PPLI scholars (personal communication with D. Fapore, Southwest District Executive Director, Pennsylvania Department of Health, November 25, 2003).

CONCLUSIONS

Workforce development in public health is challenged by the difficulty of demonstrating important outcomes, which ultimately must be measured in the improved health of populations.12 Training of individual workers may continue for years before it affects the quality of an agency's services, and the agency may sustain high quality services for even longer before they are reflected by improved health indicators. Moreover, causation between any improved competency (the basis for a training curriculum) and any measurable health indicator is probably indirect and subject to confounding influences.

PPLI, however, was designed strategically. First, the curriculum was developed in consultation with key stakeholders and was modified to suit the scholars' backgrounds and project needs. Second, the strategic definition of projects by scholar-teams encouraged the integrated functioning of emergency responders from public health and other agencies and organizations. Through work on their team projects, PPLI's scholars showed that the leadership curriculum could empower them to influence state-level policy makers concerning the organization, management, and operations of emergency response. Further, the scholars' experience with a naturally occurring infectious disease outbreak during the course of the first PPLI year suggested that this leadership training could also enhance actual performance in the field.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Edith Cook, MS, for her assistance in the analysis and presentation of data for this article.

Footnotes

This project was funded at the University of Pittsburgh through a cooperative agreement from the CDC and ASPH and at the Pennsylvania Department of Health through CDC supplemental funds for preparedness.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manning FJ, Goldfrank L, editors. Committee on Evaluation of the Metropolitan Medical Response System Program, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. Preparing for terrorism. Tools for evaluating the Metropolitan Medical Response System Program. Washington: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton V. The role of the federal government. In: Sutton V, editor. Law and bioterrorism. Carolina Academic Press: Durham (NC); 2003. pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The White House. [cited 2004 Apr 29];December 17, 2003 Homeland Security Presidential Directive/Hspd-8. Available from: URL: http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/12/20031217-6.html.

- 4.Potter MA, Eggleston MM, Gettig E, Sain A. Public health content in “all-hazards” training. A comparison of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Competencies for Public Health Workers and the Office of Domestic Preparedness' Weapons of Mass Destruction Training Program. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Center for Public Health Preparedness; 2004. [cited 2004 Apr 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.cphp.pitt.edu/upcphp/Adobe.ODPtpa.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright K, Rowitz L, Merkle A. A conceptual model for leadership development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001;7:60–6. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200107040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Setliff R, Porter JE, Malison M, Frederick S, Balderson TR. Strengthening the public health workforce: three CDC programs that prepare managers and leaders for the challenges of the 21st century. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:91–102. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Columbia University School of Nursing, Center for Health Policy. Bioterrorism & emergency readiness: competencies for all public health workers. 2002 Nov; Supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Association of Teachers of Preventive Medicine Cooperative Agreement #TS 0740. Also available from: URL: http://cpmcnet.columbia.edu/dept/nursing/institutes-centers/chphsr/btcomps.pdf.

- 8.Center for Law & the Public's Health at Georgetown & Johns Hopkins Universities, a CDC Collaborating Center Promoting Health through Law. [cited 2005 Jan 21];Model state public health laws. Available from: URL: http://www.publichealthlaw.net/Resources/Modellaws.htm.

- 9.Sweeney P. Legal preparedness for a public health response in Pennsylvania: an analysis of current authority through the lens of the Model State Emergency Health Powers Act. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Center for Public Health Preparedness; [cited 2004 Apr 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.cphp.pitt.edu/upcphp/Adobe/PALegalInfra.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woltring C, Constantine W, Schwarte L. Does leadership training make a difference? The CDC/UC Public Health Leadership Institute: 1991–1999. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:103–22. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hepatitis A outbreak associated with green onions at a restaurant—Monaca, Pennsylvania, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(D1121):1–3. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm52D1121.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potter MA, Barron G, Cioffi JP. A model for public health workforce development using the National Public Health Performance Standards Program. J Public Health Manag Practice. 2003;9:199–207. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]