Despite some recent improvements in public health preparedness in many communities, efforts to incorporate mental health plans and services into bioterrorism response planning remain in their infancy. A recent report from the Institute of Medicine recommended that “to address the prevention, health care, and promotion needs related to psychological consequences of terrorism, this area must be integrated into national, state, and local planning.”1

Bioterrorism events may produce unique consequences compared to other manmade or natural disasters.2 Fear-inducing threats of contamination, the likelihood of covert release of poisonous agents, and the possibility of contagion may result in large numbers of adverse emotional/psychological reactions. These “psychological casualties” of a bioterrorism event will likely far outnumber the medical casualties; nevertheless, response planners have been relatively slow to incorporate mental health considerations into terrorism response plans. Psychological consequences1,3–7 can be classified as distress responses (e.g., insomnia, fear, sense of vulnerability), behavioral changes (e.g., acting out, social withdrawal, increased consumption of nicotine, alcohol, or other drugs),4,5 psychosomatic symptoms and outbreaks of medically unexplained symptoms,8 psychiatric/psychological symptoms (e.g., sadness, irritability, dissociation), and psychiatric illnesses such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder.6,7

The protection and promotion of mental health in the community is a critical component of pre-event planning for bioterrorism events. Mental health elements should be included in all disaster response plans, and should be regarded with equal weight and immediacy as other elements of the plans. These mental health functions should include:9–14

Assessing and providing appropriate services;

Preparing content for and advising on the process of risk communication;

Creatively using assets belonging to the public trust (such as mental health facilities);

Consulting with community mental health leaders on the psychology of epidemics, managing fear and uncertainty, and managing responder and leadership distress;

Training local community thought leaders in group coping methods; and

Developing culturally competent interventions for frequently overlooked, vulnerable populations such as children, homeless individuals, and persons who do not speak English.

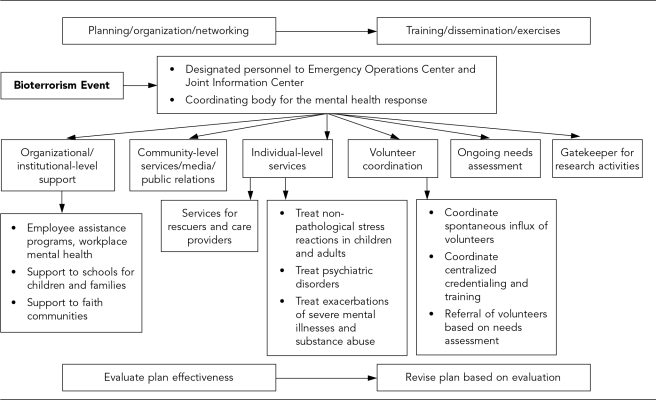

Some of these activities are shown in the Figure, which depicts an action model for a mental health response to a bioterrorism event. In sum, a mental health response includes not only the provision of services (including triage and referral) for those experiencing psychological consequences, but also culturally competent, community-based interventions (such as effective risk/health/coping communication and screening for psychological sequelae) to reduce the risk of incident disorders and disturbances.11–14 Broadcast and print media in workplace and civic/faith-based social networks may be particularly important in risk communication.

Figure. Potential action model for a mental health response to a bioterrorism event.

SOURCE: Metropolitan Atlanta Mental Health Bioterrorism Response Planning Group (assembled by the Center for Public Health Preparedness of the DeKalb County, Georgia, Board of Health, July 2002–April 2004)

While the incorporation of mental health into local bioterrorism response planning is of utmost importance, there are several barriers to such planning that should be recognized. These include:

Separation of public health agencies and public mental health agencies at the local level;

The traditional role of public-sector community mental health agencies to provide care for individuals with severe and persistent mental illnesses, combined with little practical experience in community-level public interventions that promote mental health and prevent mental disorders;

Limited collaboration between local public health agencies and the American Red Cross; and

The complex issue and varying opinions about licensing and credentialing of mental health volunteers.

First, in many jurisdictions, separate agencies are responsible for the provision of public health and mental health services at the local level. Often, local public health departments are relatively unfamiliar with mental health issues and the multitude of often fragmented mental health agencies and associations. The political, organizational, financial, and ideological separation that commonly exists between local public health and local community mental health services can create a barrier to effective communication and collaboration on issues affecting the mental health of the community, such as bioterrorism. Local public health agencies are often unaware of the many potential assets that may be brought to preparedness planning by local public mental health, including facilities (such as community mental health centers, crisis stabilization units, and addiction clinics), mental health professionals and staff, and special operations, such as 24-hour crisis hotlines and mobile crisis units that may operate in conjunction with the local police department. A key part of incorporating mental health into bioterrorism response planning is the strengthening of relationships among local public health and local community mental health agencies.

A second obstacle that may complicate the process of integrating mental health into bioterrorism response planning is related to the traditional purview of services provided by community mental health agencies. Public-sector community mental health agencies are very experienced in the domain of care for individuals with severe and persistent mental illnesses, but they often have little practical experience in the area of community-level public interventions that promote mental health and prevent mental disorders.10 It may be difficult for state or local mental health authorities to broaden their mission to include the promotion of mental health of communities with current funding and staffing levels that do not even provide sufficient funds for the comprehensive care of individuals with severe and persistent mental illnesses. Nonetheless, local community mental health agencies are likely to be quite interested in being involved in bioterrorism response planning, even if this means expanding the paradigm within which they routinely operate.

A third potential barrier exists when local public health agencies have an underdeveloped relationship with the American Red Cross (ARC), which is likely to be involved in the provision of at least some mental health services in the event of a bioterrorism attack.14 The ARC provides uniformity of structure, consistency of service, and an ability to quickly mobilize people from a variety of backgrounds and locations into effective work teams with an explicit common cause. However, local public health agencies engaged in bioterrorism response planning may be relatively unfamiliar with its structure and functions. This lack of familiarity can create barriers to effective planning. The solution is for local public health agencies to establish ongoing relationships with local ARC chapters. Often, the ARC has relationships with emergency management agencies, state and local mental health agencies, and the professional mental health associations within the state. These relationships position the ARC to play an active role in the planning process. The ARC is likely to be integral to functions such as services for rescuers and care providers, coordination of volunteers, and needs assessment (Figure).

Fourth, because of the variety of mental health professionals that may be involved in a response, the issue of licensing and credentialing of volunteers may serve as a barrier to efficient collaboration.9 Planning groups will need to consider whether a mental health professional license and willingness to provide pro bono services are sufficient for volunteering, or if a particular crisis mental health training model like the ARC's should be endorsed. Additional facets to this issue include the likely emergence of spontaneous volunteers who have had different crisis training, differences in professional opinions about the efficacy of some mental health interventions (such as crisis intervention stress debriefing), and the difficulty coordinating spontaneous volunteers who have no mental health training whatsoever. While the ARC provides standardized training and credentialing for licensed mental health professionals, other service agencies may have different ways of credentialing volunteers.14 When there has been no pre-event planning and communication about roles and procedures, civil authorities and other agencies may have expectations of services from the ARC that do not mesh with the organization's regulations and abilities. To avoid service gaps and unclear training jurisdictions, it is critical to clarify which agency is primarily responsible for ensuring delivery of mental health support for all individuals in the community in a mass casualty event.

While these potential barriers must be considered, we stress the importance of coordinating public health, mental health, and medical response through the formation of interdisciplinary planning teams, service provider networks, attention to short-term and long-term psychosocial service delivery, and accounting for the needs of special populations (e.g., the severely mentally ill, children, frail elderly, physically disabled, etc.).1,13 We recommend that local public health agencies engaging in bioterrorism response planning facilitate collaboration among their agencies and their critical partners—local public mental health/community mental health agencies, local ARC affiliates, academic institutions (local schools of medicine, schools of public health, and training programs in psychology, nursing, social work, or allied mental health professions), mental health professional associations, and federal partners. Including leaders of faith communities, school psychologists and other personnel, and large employers is also important for a comprehensive mental health component to bioterrorism response plans. Other important mental health issues to consider as part of bioterrorism preparedness planning include consistent messaging and risk communication as an aspect of the mental health response, consideration of cultural diversity of the exposed population, and the mental health needs of children, families, and employees.2,11,15

Public health preparedness is both a product and a process. The process of building relationships and ongoing collaborations with other agencies and disciplines is the most vital aspect. This is especially true of public health collaborations for bioterrorism preparedness.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butler AS, Panzer AM, Goldfrank LR, editors. Committee on Responding to the Psychological Consequences of Terrorism, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Preparing for the psychological consequences of terrorism: a public health strategy. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall M, Norwood A, Ursano R, Fullerton C. The psychological impacts of bioterrorism. Biosecur Bioterror. 2003;1:139–44. doi: 10.1089/153871303766275817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flynn BW, Norwood AE. Defining normal psychological reactions to disaster. Psych Annals. 2004;34:597–603. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vlahov D, Galea S, Resnick H, Ahern J, Boscarino JA, Bucuvalas M, et al. Increased use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana among Manhattan, New York, residents after the September 11th terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:988–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grieger TA, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol use, and perceived safety after the terrorist attack on the Pentagon. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1380–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.10.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:1235–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, Jordan BK, Rourke KM, Wilson D, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the National Study of Americans' Reactions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:581–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel CC. Outbreaks of medically unexplained physical symptoms after military action, terrorist threat, or technological disaster. Mil Med. 2001;166(Suppl 2):47–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Mental health all-hazards disaster planning guidance. Rockville (MD): Center for Mental Health Services, SAMHSA; 2003. DHHS Publication No. SMA 3829. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerrity ET, Flynn BW. Mental health consequences of disaster. In: Noji EK, editor. The public health consequences of disasters. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. pp. 101–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ursano R, Norwood A, Fullerton C, editors. Bioterrorism: psychological and public health interventions. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reissman DB. New roles for mental and behavioral health experts to enhance emergency preparedness and response readiness. Psychiatry. 2004;67:118–22. doi: 10.1521/psyc.67.2.118.35956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reissman DB, Spencer S, Tannielian T, Stein BD. Integrating behavioral aspects into community preparedness and response systems. In: Danieli Y, Brom D, Sills J, editors. The trauma of terrorism: an international handbook of sharing knowledge and shared care. Binghamton (NY): The Haworth Press; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritchie EC, Hamilton S. Assessing mental health needs following disaster. Psych Annals. 2004;34:605–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Mental Health (US) Mental health and mass violence: evidence-based early psychological intervention for victims/survivors of mass violence. Washington: NIMH, U.S. Government Printing Office; 2002. [cited 2004 July 12]. A workshop to reach consensus on best practices. NIH Publication No. 02-5138. Available from: URL: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/massviolence.pdf. [Google Scholar]