Abstract

The embryonic microenvironment is an important source of signals that program multipotent cells to adopt a particular fate and migratory path, yet its potential to reprogram and restrict multipotent tumor cell fate and invasion is unrealized. Aggressive tumor cells share many characteristics with multipotent, invasive embryonic progenitors, contributing to the paradigm of tumour cell plasticity. In the vertebrate embryo, multiple cell types originate from a highly invasive cell population called the neural crest. The neural crest and the embryonic microenvironments they migrate through represent an excellent model system to study cell diversification during embryogenesis and phenotype determination. Recent exciting studies of tumor cells transplanted into various embryo models, including the neural crest rich chick microenvironment, have revealed the potential to control and revert the metastatic phenotype, suggesting further work may help to identify new targets for therapeutic intervention derived from a convergence of tumorigenic and embryonic signals. In this mini-review, we summarize markers that are common to the neural crest and highly aggressive human melanoma cells. We highlight advances in our understanding of tumor cell behaviors and plasticity studied within the chick neural crest rich microenvironment. In so doing, we honor the tremendous contributions of Professor Elizabeth D. Hay towards this important interface of developmental and cancer biology.

Introduction

Multipotent tumor cells and many embryonic progenitor cells share common characteristics of cell fate plasticity and invasiveness, suggesting that the identification of mechanisms that regulate these processes may lead to new therapeutic targets for intervention of birth defects and cancer. The manner by which embryonic or tumor cells invade peripheral tissues involves migration through many different microenvironments and interactions with numerous other cell types and structures. The signals between the multipotent tumor or embryonic cell and its microenvironment are thought to be complex and manifested in a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. Exciting studies have recently shown that signals potentially derived from the embryonic microenvironment can influence embryonic stem cells (Hochedlinger et al., 2004; Takahashi et al, 2007; Yu et al, 2007), multipotent tumor cells (Hendrix et al., 2007), and adult cell fate and plasticity (Real et al., 2006). One of the next logical steps is to resolve the nature of the in vivo cellular and molecular mechanisms critical to the survival and programming of cell fate and invasion. Further insights from studies at the interface of developmental and tumor biology that exploit the accessibility of the embryo may help to determine the extent of the convergence of embryonic and tumorigenic signaling pathways involved in regulating cell fate and invasive ability.

Within the developing vertebrate embryo, the neural crest (NC) represents a highly migratory cell population that diversifies to multiple phenotypes to contribute to assembly of the face, function of the heart and gut, and the entire peripheral nervous system (Kalcheim and LeDouarin, 1999; Anderson et al., 2006; LeDouarin et al., 2007; Hutson and Kirby et al., 2007). NC cells undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to exit the neural tube, then sort into segregated migratory streams and invade the embryo along the vertebrate axis in a programmed rostral-to-caudal manner (Lumsden et al, 1991). Signals within the neural tube and the many different microenvironments encountered by the migratory NC are thought to spatially restrict or permit NCC movements, leading to the sculpting of NCCs into particular migratory streams that reach precise peripheral targets (Graham et al., 2004; Kulesa et al., 2004, Harris and Erickson, 2007). Time-lapse microscopy studies have revealed a complex set of NCC migratory behaviors that include active avoidance of some areas, but directed movements and cell-cell contacts through others, supporting the hypothesis that local microenvironments shape individual NCC trajectories (Schilling and Kimmel, 1994; Kulesa and Fraser, 1998; Young et al., 2004; Druckenbrod and Epstein, 2007).

Technical advances in microscopy, cell labeling, and molecular biology have allowed scientists to extend observations made by pioneers working at the intersection of developmental biology and cancer. In particular, Elizabeth Hay, her colleagues, and the students she inspired foresaw the importance of understanding basic cellular and molecular mechanisms, involving EMT and cell migration. Her efforts pioneered the development of novel cell labeling and culture techniques that extended observations of cell behaviors in 2D to in situ organ culture and helped to build the knowledge base of cell behaviors in 3D (Bilozur and Hay, 1988; Hay, 1990; Hay, 2004; Nawshad et al., 2005). Indeed, this work helped to lay the groundwork for attempts to revert or reprogram the metastatic phenotype of tumor cells by microenvironmental cues and has been an intense area of study that has benefited from new technological advances and experimental approaches (Kenny and Bissell, 2003; Bissell and Labarge, 2005).

Recent exciting investigations of tumor cell interactions within in vivo embryonic microenvironments have revealed unique insights into tumor cell behaviors and molecular signaling to inhibit tumor cell invasion and reprogram tumor cells to a more embryonic-like ancestral fate (Hendrix et al., 2007). In particular, the investigation of tumor cell behaviors within the chick NC-rich microenvironment of the embryo may exploit the ancestral link between the neural crest and cancer cell types, such as melanoma and neuroblastoma. The accessibility of novel cellular and molecular imaging strategies within embryos has inspired developmental and cancer biologists to move from descriptive observational studies to mechanistic analyses of the convergence of embryonic and tumorigenic signaling pathways. In this mini-review, we highlight advances in the study of reprogramming multipotent tumor cells with the embryonic neural crest microenvironment.

Neural crest derivatives

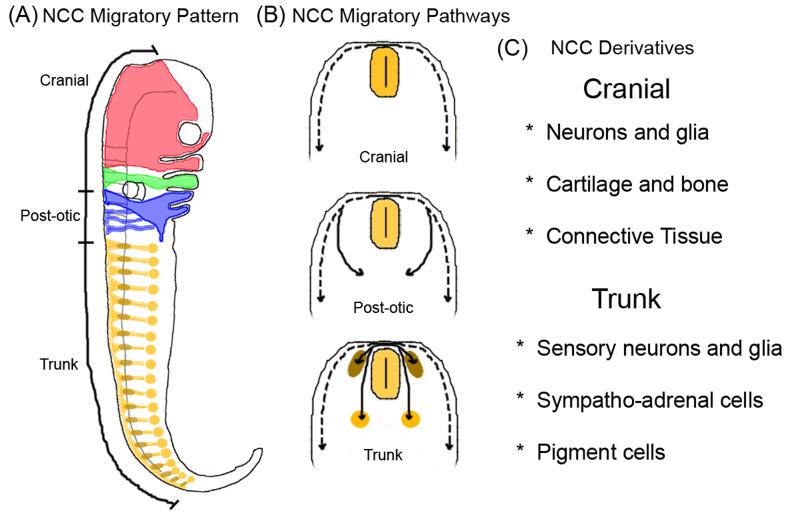

NCC patterning is intimately connected to the early segmentation of the neural tube, such that NCCs migrate in discrete segregated streams in the head and trunk and give rise to multiple derivatives (Lumsden and Krumlauf, 1996) (Fig. 1). Despite an incredible range of individual cell behaviors, NCC migratory pathways are remarkably similar in nearly all vertebrates (Serbedzija et al., 1989; Raible et al., 1992; Trainor et al., 2002; Kulesa et al., 2004; Epperlein et al., 2007). The stereotypical NCC migratory pattern is thought to be achieved in part by signaling from local microenvironments that restrict uncontrolled invasion, but permit cell movements along particular routes. Over the past several years, we have learned of several candidate molecules that either restrict the mixing of NCC streams or direct cell movements (Smith et al., 1997; Golding et al., 2000; Krull et al., 1997; Smith and Graham, 2001; Sauka-Spengler and Bronner-Fraser, 2006).

Figure 1.

The neural crest cell stereotypical migratory pathways and derivatives. (A) Neural crest cells form migratory streams throughout the embryo, patterning the craniofacial area (red and green streams), the post-otic region (blue streams) that leads to the cardiovascular and enteric neural crest contribution, and the trunk migratory streams (yellow) that shape the peripheral nervous system and pigment cell contributions. (B) Neural crest cells migrate along distinct pathways that range from dorsolateral to medioventral. (C) Neural crest cells give rise to a wide variety of derivatives, a subset of which are shown.

Now, there is emerging evidence that molecules that play a role in NCC pathfinding have common expression in highly aggressive and non-aggressive tumor cells (Table 1). Of particular interest, aggressive melanoma cells upregulate a subset of both NCC guidance molecules and differentiation markers compared to their non-aggressive counterpart. We have highlighted the inhibitory influence of neuropilin/semaphoring signaling on defining NCC migratory pathways and invasion and in our analysis, neuropilin-1 is upregulated 28-fold on metastatic melanoma cells compared to non-metastatic melanoma cells (Table 1). Interestingly, forced expression of Sema3F on certain cancer cell lines, including metastatic melanoma cells, inhibited cell growth and cells did not metastasize when transplanted into nude mice (Xiang et al., 2002; Bielenberg et al., 2004)

| Neural Crest Cell Markers* | C8161 | C81-61 |

|---|---|---|

| BMP-2 | A | A |

| Cadherin-2 | P | P |

| Cadherin-6B | A | A |

| Cadherin-7 | A | A |

| Cadherin-11 | A | A |

| Cdc42 | P | P |

| c-kit | A | A |

| Connexin-43 | P ↑ 37** | A |

| CXCR4 | P ↑ > 100 | A |

| Dlx2 | A | A |

| Dlx5 | A | A |

| Endothelin-3 | A | A |

| EphB2 | P ↑ 14 | A |

| EphA4 | P ↑ 4.2 | A |

| ErbB2 | P | M |

| EphB3 | A | A |

| FoxD3 | A | A |

| HNK-1 | P | P ↓ 1.9† |

| Hoxa1 | A | A |

| Hoxa2 | A | A |

| Hoxb1 | A | A |

| Hoxb2 | P ↑ 3.0 | P |

| Integrin A4 | A | A |

| Integrin B1 | P ↑ 3.0 | P |

| Integrin B3 | P | P ↓ 2.0 |

| Krox20 (EGR2) | A | A |

| MMP2 | P ↑ 32 | P |

| Msx1 | P | P |

| NCAM | P | P |

| Nestin | A | P ↓ > 100 |

| Neuregulin-1 | A | A |

| Neurogenin-1 | A | A |

| Neurogenin-2 | A | A |

| Neuropilin-1 | P ↑ 28 | A |

| Neuropilin-2 | P ↑ 3.0 | P |

| P75 (NGFR) | A | A |

| Pax7 | A | A |

| PDGFRa | A | A |

| PlexinA1 | P | P ↓ 2.6 |

| Ret | --‡ | -- |

| RhoA | P | P |

| RhoB | P | P ↓ 2.1 |

| Robo1 | P | P |

| Robo2 | -- | -- |

| Snail1 | A | A |

| Snail2 | -- | -- |

| Sox9 | P ↑ 13 | A |

| Sox10 | -- | -- |

| Tyrosine Hydroxylase | A | A |

| Wnt1 | A | A |

| Wnt3a | A | A |

Altered gene expression in human melanoma was identified by oligonucleotide microarray analysis (Affymetrix U133A chip). Selected neural crest marker genes are reported as a fold difference ratio of the highly aggressive C8161 to the poorly aggressive C81-61 melanoma cells. (A) indicates the absence of expression; (P) indicates the presence of expression; (M) indicates a minimal presence.

Arrow pointed up indicates an increase in expression.

Arrow pointed down indicates an increase in expression.

Gene was not represented on the U133A chip.

How are NCCs guided to a particular peripheral target? There is emerging evidence for axonal guidance molecules in regulating NCC behaviors. For example, neuropilin-semaphorin signaling has been revealed to play a role in NCC pathfinding (Eickholt et al., 1999). Neuropilin is a transmembrane protein initially identified by Fujisawa and colleagues (Takagi et al., 1995; Fujisawa et al., 1997) and shown to be a receptor for the axonal chemorepellant semaphorin III (He and Tessier-Lavigne, 1997). In mouse embryos mutant for Npn2 or its corresponding ligand sema3F, the segmental pattern of trunk NCC migration is disrupted. NCCs expressing Npn2 avoid sema3F-expressing cells, present in the posterior half of each somite (Gammill et al., 2006). Interestingly, the downrange segmental patterning of sensory and sympathetic ganglia appears to be regulated by distinct molecular families. The primary sympathetic ganglia (SG) appear to be regulated by an interplay of Eph/ephrin and N-Cadherin signaling. In chick embryos, trunk NCCs that express EphB2 reach the ventral target location adjacent to the dorsal aorta, then spread out along the antero-posterior axis before re-aggregating into distinct clusters of primary SG that express N-cadherin (Kasemeier-Kulesa et al., 2005). When N-cadherin or ephrinB1 are blocked, the SG size is altered and the segmental pattern is disrupted (Kasemeier-Kulesa et al., 2006). Neuropilin signaling also appears to be involved in cranial NCC migration, influencing the position of early migratory NCCs near the hindbrain (Yu and Moens, 2005; Osborne et al., 2005; Gammill et al., 2007) and invasion of the branchial arches (McLennan and Kulesa, 2007).

Although many inhibitory molecules have previously been identified as playing a role in restricting NCCs to a particular migratory route (Wang and Anderson, 1997; Krull et al., 1997; Santiago and Erickson, 2002; Graham, 2003; Gammill et al., 2006), permissive signals that direct NCCs have been less well-characterized. More recently, members of the chemokine family of attractant molecules have become popular players in directing cell movements during different stages of development. Not only do chemokines play an integral role in diseases marked by inflammation, but they have recently been shown to play a role in the development of the nervous system, modulating neuronal survival and migration. Recent in vivo work has revealed a role for chemokines to positively direct the migration of NCCs from the neural tube to the dorsal root ganglia to become sensory neurons (Chalasani et al., 2003; Belmadani et al., 2005). In some cases SDF-1 is not an attractant molecule on its own, but functions to reduce the repellent effect of inhibitory molecules, including Slits and semaphorins (Chalasani et al., 2007). However, chemokine signaling does not seem to be associated with any particular cell type and is widely utilized when there is a requirement to move cells from one position to another, such as during migration.

How is a NC progenitor cell driven to adopt one of its many possible fates and can this program be altered? NCCs ultimately differentiate into an astounding array of adult structures (Fig. 1). The fate of an individual NCC is thought to be influenced by a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors acting within the neural tube, along the migratory pathways, and at peripheral targets (Trainor and Krumlauf, 2000, LeDouarin et al, 2004; Taneyhill and Bronner-Fraser, 2005). In the trunk, some NCCs are restricted to particular fates at early migratory stages and this appears to dictate the cell’s migratory pathway (Harris and Erickson, 2007). Studies have revealed that specific receptor-ligand relationships expressed at the onset of migration modulate a trunk NCC’s choice of the ventral or dorsolateral migratory pathway in a spatio-temporal manner that leads to formation of the sympathetic, sensory, and pigment cell phenotypes (Santiago and Erickson, 2002; Jia et al., 2005). Interestingly, multipotent cells may still remain at later stages of NC development (LeDouarin and Dupin, 2003; LeDouarin et al., 2004). When quail NC-derived pigment cells are isolated from the skin and clonally cultured in vitro, the cells are able to generate glial and myofibroblastic cells (Real et al., 2006), consistent with in vivo cell tracing experiments in chick that revealed the NCC population to include multipotent precursors (Bronner-Fraser and Fraser, 1988).

Interestingly, small subgroups of trunk NCCs within a migratory population may selectively adopt a particular fate. Analysis of presumptive sympathetic neurons that differentiate from signals at the dorsal aorta selectively adopt a sympathetic fate, leaving neighboring NCCs to remain in a progenitor state through Notch signaling (Tsarovina et al., 2008). Reprogramming of cells with a developmental origin from the cranial NC is also possible. Corneal keratocytes (with a developmental origin from the cranial NC) injected back into the cranial NCC migratory pathway contribute to several other structures of the host, including blood vessels and cardiac cushion tissue, but do not form neurons or cartilage, illustrating that these cells maintain their restricted plasticity (Lwigale et al., 2005). These studies reveal the important influence of microenvironmental cues on the reversibility of differentiated cells.

Development of an avian model for studies of the neural crest and melanoma

One of the strongest links between common mechanisms that underlie NCC migration and cancer biology has come from the study of NCC delamination from the neural tube (Barrallo-Gimeno et al., 2005). Work on Snail2, a transcription factor expressed in early emerging NCCs, has revealed that it represents an acquisition of migratory properties partly due to repressing E-cadherin transcription during development (Cano et al., 2000; Bolos et al., 2003). Studies of cell invasion in ductal carcinomas have discovered a role for Snail in the metastatic cascade, thus highlighting its potential as an early biomarker for tumor metastatic potential (Blanco et al, 2002). These studies suggest there is a great deal to be learned from the examination of embryonic signals guiding cell migration and their potential ability to regulate tumor cell invasion. Thus, the accessible NCC rich microenvironment provides fertile ground to search for molecular signals common to the NCC invasive/migratory program and multipotent, tumorigenic potential.

The evolution of in vivo developmental models to study embryonic and tumor cell behaviors has a rich history. Pioneering groups realized the importance of simulating a natural environment for the study of migratory cells and described cell behaviors in 3D organ culture that were quite different from the 2D scenario (Tickle and Trinkaus, 1976; Bilozur and Hay, 1988; Hay, 1990). In 1975, Mintz and Illmensee investigated the concept that the mouse embryo was accessible to transplantation of tumor cells and found that signals within the microenvironment could reprogram the tumor cells to a less destructive fate. When the hypothesis of multipotent tumor cell reprogramming was investigated more recently in the zebrafish embryo, one of the results surprisingly showed that transplanted highly aggressive human melanoma cells induced zebrafish progenitor cells to form a secondary axis (Topczewska et al., 2006). Further investigation revealed that the aggressive melanoma cells secrete Nodal, (a potent embryonic morphogen), responsible for the ectopic induction of the embryonic axis (Topczewska et al., 2006). Thus, utilizing the zebrafish embryo as a biosensor for tumor cell signals combines the strengths of optical imaging with a system accessible to manipulation and molecular analyses.

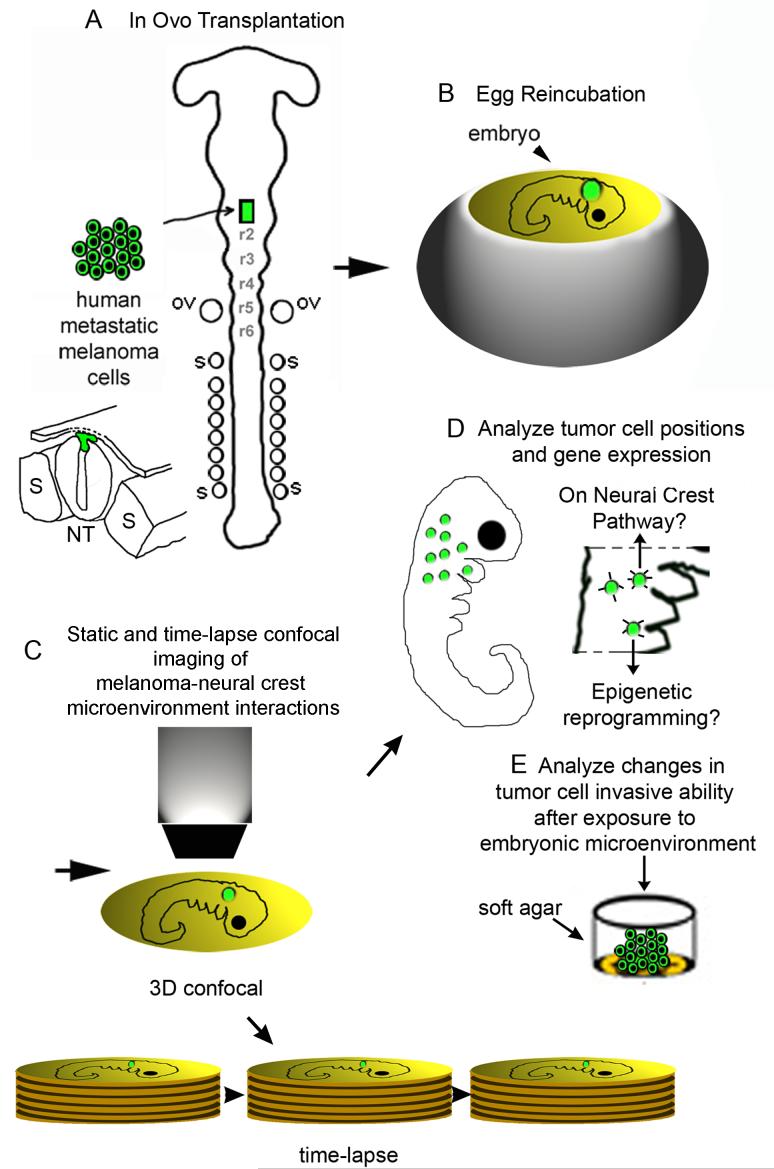

The avian embryo has emerged as a useful tool for analyzing both NC and tumor cell interactions, providing imaging and surgical accessibility to manipulate the NCC migratory pathways and monitored transplantated tumor cells (Fig. 2). One of the major results of these types of studies occurred as early as the 1950’s, when tissue transplantation experiments that placed mouse sarcoma 180 cells into the chick limb bud caused NC-derived sympathetic nerve fibers to grow out and innervate the transplanted cells (Levi-Montalcini et al., 1952). Investigation of the tumor cell and nerve fiber interactions led to the discovery of nerve growth factor (NGF) as the secreted attractive signal from the sarcoma 180 cells (Levi-Montalcini et al., 1952). If transplanted tumor cells can influence cell movements in the host embryo, the question arises as to the extent the host cell migratory pathways can influence other migratory cell types. Early studies that investigated the influence of the NC-rich microenvironment employed transplantation of a variety of migratory cell types into the avian trunk NCC migratory pathway (Erickson, Tosney, and Weston, 1980). When transplanted sarcoma 180 cells were analyzed after embryo reincubation, the cells were distributed along normal trunk NC pathways and usually seen as individual cells; fibroblasts, however, remained at the transplant site (Erickson, Tosney and Weston, 1980). Moreover, the invasive characteristics of chick NCCs can be studied in vitro using a modified Boyden Chamber assay, as previously demonstrated by our laboratory (Gehlsen and Hendrix, 1987). Recent work supports the hypothesis that adult tumor cells can follow host embryo NCC migratory pathways. Injection of human SK-Mel-28 (melanoma) or transplantation of C8161 aggressive melanoma cells into the chick embryo neural tube revealed that the tumor cells invaded the embryo along host NCC cranial (Kulesa et al., 2006) and trunk (Shriek et al., 2005) migratory pathways, and did not form tumors. In contrast, when B16 mouse melanoma cells were injected into non-NCC microenvironments of the chick embryo, including the eye cup, the tumor cells invaded and formed melanomas (Oppitz et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

Schematic outline of tumor cell transplantation experiments and imaging analysis. (A) In ovo transplantation of human metastatic melanoma cells into the chick neural tube and (B) egg re-incubation. (C) After egg re-incubation, the invading tumor cell positions are analyzed with static and time-lapse confocal analysis for (D) positioning along host neural crest cell migratory pathways, changes in gene expression, and invasive ability. (E) Invading tumor cells within the chick embryo are extracted by FACS and evaluated in soft agar for invasive ability. The schematic is modified from Hendrix et al., 2007

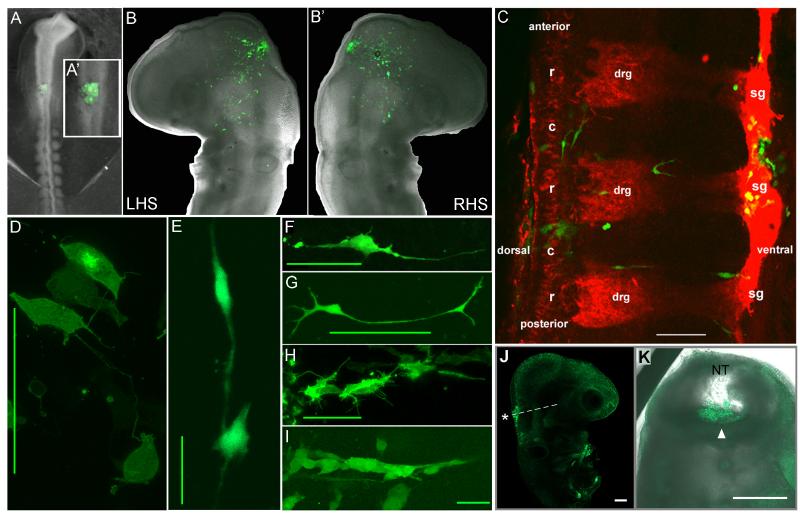

Innovative imaging strategies have begun to reveal an amazing complexity of tumor and embryonic cell behaviors when visualized in vivo within developmental microenvironments (Wyckoff et al., 2007; Sidani et al., 2007; Fukumura and Jain, 2007); yet it is still a major challenge to integrate information on cell behaviors and molecular signals. Interestingly, 3D confocal analysis of GFP-labeled C8161 aggressive melanoma cells within the chick embryo NCC microenvironment demonstrated tumor cells resembling host NCC morphologies, including long filopodial extensions that contact neighboring cells and formed follow-the-leader chain-like arrays (Fig 3). When we investigated the positions of transplanted invading melanoma cells, the results showed that the tumor cells avoided typical NCC-free zones and did not require a host NCC scaffold to invade (Kulesa et al., 2006). This suggests that the chick embryonic NCC-rich microenvironment has a strong influence on adult tumor cell types with an ancestral link to the NC.

Figure 3.

Transplanted metastatic melanoma cells invade chick neural crest cell migratory pathways and destinations. (A-A’) Adult GFP-labeled human metastatic melanoma cells (C8161) were transplanted into specific neural tube locations in host chick embryos (6-9 somite stage). Eggs were resealed and re-incubated for 48hrs. (BB’) Transplanted melanoma cells invade host tissue and spread out into the chick craniofacial (RHS is right-hand side) and (C) trunk, including the dorsal root ganglia (drg) and sympathetic ganglia (sg). (D-I) Transplanted tumor cell morphologies resemble host neural crest cell shapes. (J-K) Non-aggressive melanoma cells transplanted into close contact with the neural tube (A-A’) into similar regions of the chick neural tube at the same 6-9 somite stage remain at the transplant site. Some tumor cells may appear at the ventral lumen of the neural tube due to morphogenesis of the neural tube volume and failure of the cells to egress. Data presented in (A-C, F-K) are reproduced from Kulesa et al., 2006; otherwise are unpublished from KCKK and PMK. Scalebars are (C) 10um, (D,F,H,I) 50um, (E) 100um, (G) 200um, (J-K) 100um.

Investigating the developmental plasticity of human multipotent melanoma cells in an embryonic chick model

Metastatic melanoma cells down-regulate melanocyte-specific markers, consistent with a dedifferentiated phenotype (Postovit et al., 2006). To further our understanding of the biological relevance of melanoma plasticity, we began to study the fate of melanoma cells in a chick embryo model because the application of developmental biology principles to the study of cancer biology has the potential to yield new perspectives on tumor cell plasticity. In the developing vertebrate embryo, the normal patterning of peripheral structures and pigment cells of the skin involves the invasion of the neural crest. Collectively, our observations of the plastic phenotype of melanoma cells and our experimental model of the NC, led us to hypothesize that metastatic melanoma cells could respond to an embryonic microenvironment experienced by their ancestral cell type, the NC.

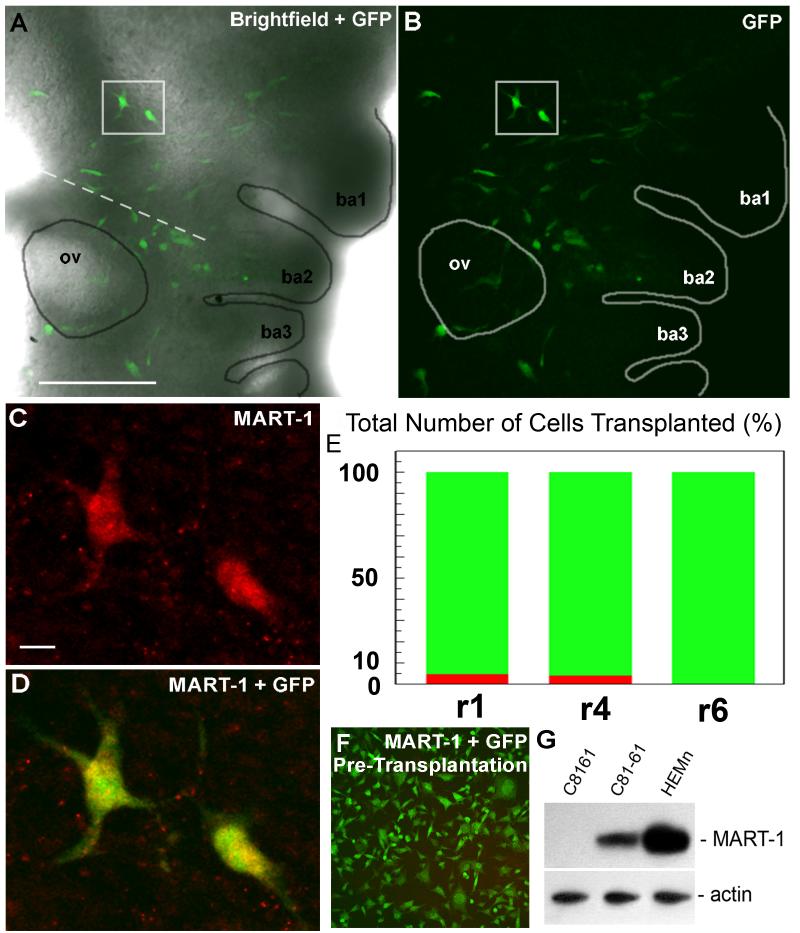

To test whether transplanted human metastatic melanoma cells express phenotype-specific genes associated with the acquisition of a neural crest melanocyte-like phenotype, we examined chick embryos for the immunolocalization of MART-1, a melanocyte differentiation antigen, expressed on both melanocytes and differentiated melanoma cells that are poorly or moderately aggressive (Takeuchi et al., 2003). However, the metastatic (amelanotic) tumor cells used in this study have been shown to be negative for MART-1 (Hendrix et al., 2003). We found that a subset of transplanted GFP-labeled melanoma cells that invade the chick periphery were MART-1-positive (Fig. 4). Individual tissue sections of the chick embryo confirmed that a number of transplanted GFP-labeled melanoma cells expressed MART-1 (Fig. 4). Specifically, the number of MART-1-positive melanoma cells was 5% and 3.4% of the total number of transplanted tumor cells into r1 and r4, respectively (Fig. 4). Before transplantation, the GFP-labeled melanoma cells do not express MART-1 by immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4). In addition, Western blot analysis for the expression of MART-1 in cell lysates of the human melanoma cell lines C8161 and C81-61, as well as the human melanocyte cell line HEMn, confirmed that the metastatic tumor cells used in this study (C8161) were negative for MART-1 (Fig. 4), whereas their isogenic, poorly aggressive counterpart C81-61 and normal melanocytes HEMn were positive. Taken together our results suggest that human metastatic melanoma cells respond to and are influenced by the chick embryonic NC-rich microenvironment, which may hold significant promise for new therapeutic strategies.

Figure 4.

Transplanted tumor cells express melanocyte-like markers. (A- E) Expression analysis of MART-1 shows a small subset of transplanted tumor cells with expression. (F-G) The GFP-labeled tumor cells do not express MART-1 prior to transplantation. The source of the material is from Kulesa et al., 2006. All scalebars are 100um.

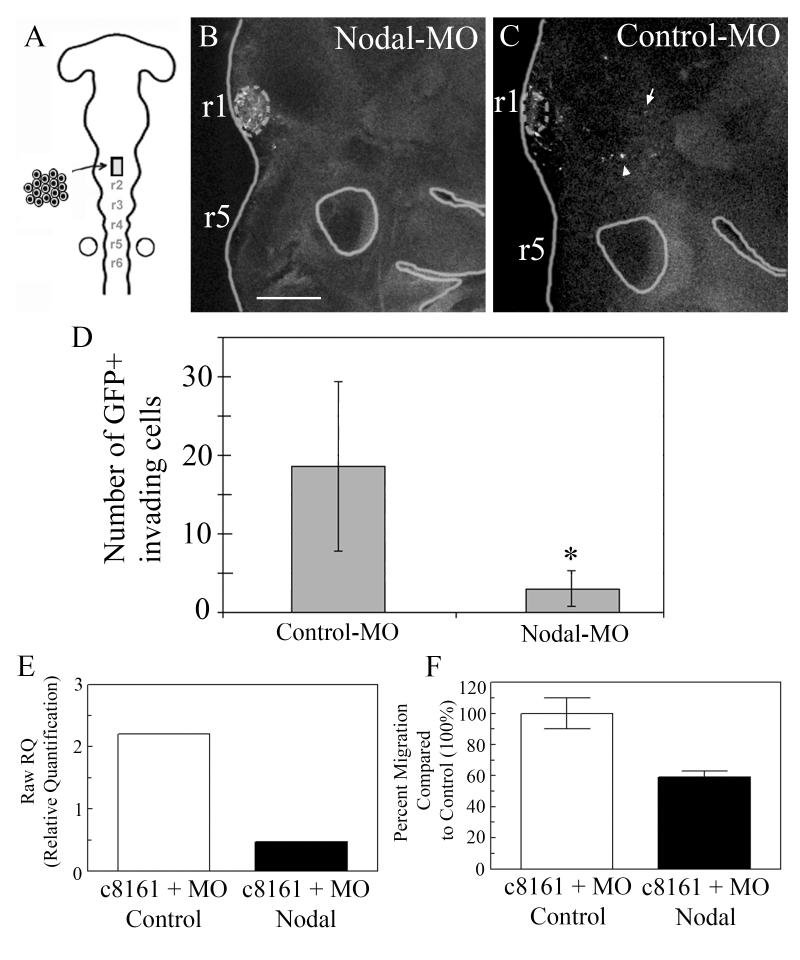

Knock down of Nodal in melanoma cells results in decreased migratory activity in vitro and in the chick neural crest microenvironment

Recently, the embryonic morphogen and stem cell–associated marker Nodal has been shown to be expressed by metastatic melanoma cells but not non-aggressive melanoma or normal skin cells (Topczewska et al., 2006). A reduction of Nodal expression/signaling by inhibiting Notch results in a dramatic reduction in melanoma tumorigenicity in a nude mouse. Extrapolating the role of Nodal signaling in reversion of the metastatic phenotype, we asked how Nodal-deficient melanoma cells might respond in the chick embryonic NC microenvironment. If Nodal is a biomarker for melanoma plasticity, one hypothesis would predict that knock down of Nodal signaling would prevent the tumor cells from interpreting microenvironmental cues and invading the embryonic periphery. Furthermore, if tumor cells are unable to incorporate into the embryonic periphery along NC cell migratory routes, will these tumor cells maintain the ability to assume a NC cell-like phenotype? In the embryo, trunk NC cells cannot complete their differentiation program if they don’t reach their destination site. In the ErbB2/neuregulin knockout mice, NC cells fail to reach the dorsal aorta, the site of primary sympathetic ganglia formation and hence, fail to differentiate into sympathetic neurons (Britsch et al., 1998).

Nodal may be able to control metastatic ability, but in order to be reprogrammed, are these cells required to migrate along or arrive at NC cell destinations to assume a non-metastatic-like phenotype? Interestingly, we show that when Nodal signaling is disrupted in C8161 melanoma cells that are transplanted into the chick embryonic NC microenvironment, the tumor cells failed to migrate and populate NC cell migratory streams and peripheral targets (Fig. 5A-D). Importantly, six-fold more cells were found in the periphery of control vs. Nodal-morpholino transplanted embryos (Fig. 5A-D). In functional studies where Nodal expression was significantly down-regulated (using Nodal morpholinos) in the C8161 human metastatic melanoma cells, the migratory ability of these tumor cells was reduced by 40% compared with control morpholino treated tumor cells (Figure 5E, F). Migration was measured in vitro over 6 hours using a modified Boyden chamber containing a gelatin-coated porous membrane. Interestingly, these in vitro data support the in vivo chick embryo findings showing a dramatic reduction in the migratory capacity of transplanted C8161 melanoma cells treated with Nodal morpholinos. Collectively, these data highlight the importance of Nodal signaling underlying the migratory and invasive behavior of highly aggressive melanoma tumor cells and their plastic phenotype. It will be intriguing to determine whether knock-in of their ability to migrate along NC cell migratory paths also blocks their ability to assume a NC cell-like phenotype, as is seen with the non-metastatic C81-61 cells.

Figure 5.

C8161 melanoma cells transfected with an anti-Nodal GFP morpholino were transplanted into the cranial region of host unlabeled chick embryos at Hamburger and Hamilton Stages 8-9. (B) A confocal image of a typical chick embryo at +48hrs of reincubation including transplanted melanoma (dotted circled clump). (C,D,E) Many melanoma cells transfected with a control GFP morpholino invade the host chick embryo (see the arrow and arrowhead). Graph of the cell counts of GFP+ invading cells in both the control-MO (n=10) and Nodal-MO (n=14) (p<0.001). (E) Relative quantification (RawRQ) of Nodal expression by aggressive C8161 human metastatic melanoma cells treated with either a control or Nodal morpholino (MO) as measured by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. (F) Percent migration (measured over 6 hours in a modified Boyden chamber containing a gelatin-coated porous membrane) of C8161 cells treated with either a control or Nodal morpholino (MO), with the control treated cells normalized to 100% (n=4, average ± S.E.). These data are unpublished. The scalebar is 150um (B).

Perspectives

The microenvironment exerts control over the genome and phenotype of both normal and cancer cells and plays a crucial role in the determination of cell fate. Within this relationship are possible cues for new therapeutic strategies. However, particularly challenging to the development of effective therapies is the issue of tumor cell plasticity, and, although this is a shared common property with normal embryonic cells, the most notable difference is an abnormal vs. a normal outcome, respectively. Indeed, there is compelling evidence presented in the literature detailing the molecular signature of multipotent tumor cells, as well as embryonic stem and progenitor cells, that demonstrate the underlying plasticity of these collective cell types. For example, comparative global gene analyses of aggressive and poorly aggressive human melanoma cell lines have revealed that the aggressive tumor cells express genes (and proteins) associated with multiple cellular phenotypes (including progenitor and stem cells), while simultaneously downregulating genes specific to their parental melanocytic lineage (Postovit et al., 2007). Particularly noteworthy are aggressive melanoma cells that show a significant downregulation in pigmentation pathway-associated genes, such as Melan-A (MLANA) and tyrosinase, compared with their poorly aggressive, isogenically matched counterparts, and this dedifferentiated phenotype has been correlated with a poor clinical outcome (for review, see Hendrix et al., 2007). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that a viable strategy for re-differentiating the aggressive, plastic melanoma cell phenotype back to a melanocyte-like cell, might lead to the suppression of metastasis.

During normal embryonic development, precursor cells undergo cell fate specification via the autocrine and paracrine delivery of signaling molecules, including spatial distribution along programmed pathways, as exquisitely demonstrated by NCCs. During cancer progression, malignant cells such as multipotent melanoma cells similarly secrete and receive molecular cues that promote tumor growth and dissemination. Recent evidence highlighted here has revealed an important linkage underlying the convergence of embryonic and tumorigenic signaling via Nodal -- an embryonic morphogen aberrantly expressed by melanoma and a critical regulator of embryonic stem cell fate. Furthermore, inhibition of Nodal signaling in multipotent melanoma cells leads to an abrogation of tumor formation in vivo and loss of the plastic metastatic phenotype (Postovit et al., 2008). Therefore, with these unique similarities and differences in mind, we followed the inspirational strategy of several developmental pioneers, including Betty Hay, and specifically asked if the chick NCC microenvironment could reprogram human multipotent melanoma cells. New technology advances in tumor cell transplantation and tracking in an embryonic chick model, together with NCC labeling, and time-lapse confocal imaging, allowed novel observations demonstrating the reprogramming of a subset of metastatic melanoma cells to a melanocyte-like phenotype as they migrated along NCC pathways. In addition, down-regulation of Nodal expression in multipotent melanoma cells resulted in a dramatic loss of their plastic phenotype and migratory ability along NCC pathways.

The use of embryonic models to study tumor cell phenotype determination offers an innovative approach to investigate the boundaries of tumor cell plasticity and the potential for reprogramming this deadly cell type by targeting the convergence of embryonic and tumorigenic signaling pathways.

Acknowledgements

PMK would like to thank Mr. and Mrs. Stowers for their generous support. This research was supported by CA50702 and CA121205 from the NIH/NCI.

References

- Anderson RB, Newgreen DF, Young HM. Neural crest and the development of the enteric nervous system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;589:181–96. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrallo-Gimeno A, Nieto MA. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Dev. 2005;132:3151–3161. doi: 10.1242/dev.01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmadani A, Tran PB, Ren D, Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA, Miller RJ. The chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 regulates the migration of sensory neuron progenitors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3995–4003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4631-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielenberg DR, Hida Y, Shimizu A, Kaipainen A, Kreuter M, Kim CC, Klagsbrun M. Semaphorin 3F, a chemorepulsant for endothelial cells, induces a poorly vascularized, encapsulated, nonmetastatic tumor phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1260–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI21378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilozur ME, Hay ED. Neural crest migration in 3D extracellular matrix utilizes laminin, fibronectin, or collagen. Dev Biol. 1988;125:19–33. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissell MJ, Labarge MA. Context, tissue plasticity, and cancer: are tumor stem cells also regulated by the microenvironment? Cancer Cell. 2005;7:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco MJ, Moreno-Bueno G, Sarrio D, Locascio A, Cano A, Palacios J, Nieto MA. Correlation of Snail expression with histological grade and lymph node status in breast carcinomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:3241–3246. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolos V, Peinado H, Perez-Moreno M, Fraga MF, Estreller M, Cano A. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: a comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:449–511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S, Li L, Kirchhoff S, Theuring F, Brinkmann V, Birchmeier C, Riethmacher D. The ErB2 an d ErbB3 receptors and their ligand, neuregulin-1, are essential for development of the sympathetic nervous system. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1825–1836. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner-Fraser M, Fraser SE. Cell lineage analysis reveals multipotency of some avian neural crest cells. Nature. 1988;335:161–164. doi: 10.1038/335161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Perez-Moreno M, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco M, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani SH, Sabelko KA, Sunshine MJ, Littman DR, Raper JA. The chemokine, SDF-1, reduces the effectiveness of multiple axonal repellants and is required for normal axon pathfinding. J. Neurosci. 2003;23(4):1360–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani SH, Sabol A, Xu H, Gyda MA, Rasband K, Granato M, Chien CB, Raper J. Stromal cell derived factor -1 antagonizes slit/robo signaling in vivo. J Neuro. 2007;27(5):973–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4132-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Barrio MG, Nieto MA. Overexpression of Snail family members highlights their ability to promote chick neural crest formation. Dev. 2002;129:1583–1593. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.7.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druckenbrod NR, Epstein ML. Behavior of enteric neural crest-derived cells varies with respect to the migratory wavefront. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:84–92. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickholt BJ, Mackenzie SL, Graham A, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Evidence for collapsin-1 functioning in the control of neural crest migration in both trunk and hindbrain regions. Dev. 1999;126:2181–2189. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperlein HH, Selleck MA, Meulemans D, Mchedlishvili L, Cerny R, Sobkow L, Bronner-Fraser M. Migratory patterns and developmental potential of trunk neural crest cells in the axolotl embryo. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:389–403. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson CA, Tosney KW, Weston JA. Analysis of migratory behavior of neural crest and fibroblastic cells in embryonic tissues. Dev Biol. 1980;77:142–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa H, Kitsukawa T, Kawakami A, Takagi S, Shimizu M, Hirata T. Roles of a neuronal cell surface molecule, neuropilin, in nerve fiber fasciculation and guidance. Cells Tissue Res. 1997;290(2):465–70. doi: 10.1007/s004410050954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor microenvironment abnormalities: cases, consequences, and strategies to normalize. J. Cell Biochem. 2007;101:937–949. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Gonzalez C, Bronner-Fraser M. Neuropilin 2/semaphoring 3F signaling is essential for cranial neural crest migration and trigeminal ganglion condensation. J Neurobiol. 2007;67:47–56. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Gonzalez C, Gu C, Bronner-Fraser M. Guidance of trunk neural crest migration requires neuropilin 2/semaphoring 3F signaling. Dev. 2006;133:99–106. doi: 10.1242/dev.02187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlsen KR, Hendrix MJ. Invasive characteristics of neural crest cells in vitro. Pigment Cell Res. 1987;1:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1987.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JP, Trainor P, Krumlauf R, Gassmann M. Defects in pathfinding by cranial neural crest cells in mice lacking the neuregulin receptor ErbB4. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:103–109. doi: 10.1038/35000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A, Begbie J, McGonnell I. Significance of the cranial neural crest. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:5–13. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris ML, Erickson CA. Lineage specification in neural crest cell pathfinding. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:1–19. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ED. The extracellular matrix in development and regeneration. An interview with Elizabeth D. Hay. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:687–694. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041857rt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ED. Role of cell-matrix contacts in cell migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Cell Differ Dev. 1990;32:367–375. doi: 10.1016/0922-3371(90)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Tessier-Lavigne Neuropilin is a receptor for the axonal chemorepellant semaphoring III. Cell. 1997;90(4):739–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Kulesa PM, Postovit LM. Reprogramming metastatic tumour cells with embryonic microenvironments. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;4:246–255. doi: 10.1038/nrc2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJ, Seftor EA, Hess AR, Seftor RE. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: Lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochedlinger K, Blelloch R, Brenna C, Yamada Y, Kim M, Chin L, Jaenisch R. Reprogramming of a melanoma genome by nuclear transplantation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1875–1885. doi: 10.1101/gad.1213504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson MR, Kirby ML. Model systems for the study of heart development and disease. Cardiac neural crest and conotruncal malformations. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(1):101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Cheng L, Raper J. Slit/Robo signaling is necessary to confine early neural crest cells to the ventral migratory pathway in the trunk. Dev Biol. 2005;282:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalcheim C, Le Douarin N. The Neural Crest. Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Bradley R, Pasquale EB, Lefcort F, Kulesa PM. Eph/ephrins and N-cadherins coordinate to control the pattern of sympathetic ganglia. Dev. 2006;133:4839–4847. doi: 10.1242/dev.02662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Kulesa PM, Lefcort F. Imaging neural crest cell dynamics during formation of dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. Dev. 2005;13:235–245. doi: 10.1242/dev.01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PA, Bissell MJ. Tumor reversion: correction of malignant behavior by microenvironment cues. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:688–695. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull CE, Lansford R, Gale NW, Collazo A, Marcelle C, Yancopoulos GD, Fraser SE, Bronner-Fraser M. Interactions of Eph-related receptors and ligands confer rostrocaudal pattern to trunk neural crest migration. Curr Biol. 1997;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa PM, Fraser SE. Neural crest cell dynamics revealed by time-lapse video microscopy of whole embryo chick explant cultures. Dev Biol. 1998;204:327–344. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa P, Ellies DL, Trainor PA. Comparative analysis of neural crest cell death, migration, and function during vertebrate embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:14–29. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa PM, Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Teddy JM, Margaryan NV, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Hendrix MJ. Reprogramming metastatic melanoma cells to assume a neural crest-cell like phenotype in an embryonic microenvironment. PNAS. 2006;103(10):3752–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506977103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Dupin E. Multipotentiality of the neural crest. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Creuzet S, Couly G, Dupin E. Neural crest cell plasticity and its limits. Dev. 2004;131:4637–4650. doi: 10.1242/dev.01350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM, Brito JM, Creuzet S. Role of the neural crest in face and brain development. Brain Res Rev. 2007;55(2):237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R, Meyer H, Hamburger V. In vitro experiments on the effects of mouse sarcomas 180 and 37 on the spinal and sympathetic ganglia of the chick embryo. Cancer Res. 1952;14:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden A, Sprawson N, Graham A. Segmental origin and migration of neural crest cells in the hindbrain region of the chick embryo. Dev. 1991;113:1281–1291. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden A, Krumlauf R. Patterning the vertebrate neuraxis. Science. 274(5290):1109–15. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lwigale PY, Cressy PA, Bronner-Fraser M. Corneal keratocytes retain neural crest progenitor cell properties. Dev Biol. 2005;288:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan R, Kulesa PM. In vivo analysis reveals a critical role for neuropilin-1 in cranial neural crest cell migration in chick. Dev Biol. 2007;301:227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B, Illmensee K. Normal genetically mosaic mice produced from malignant teratocarcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1975;72:3585–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawshad A, Lagamba D, Polad A, Hay ED. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling during epithelial-mesenchymal transformation: implications for embryogenesis and tumor metastasis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;189:11–23. doi: 10.1159/000084505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppitz M, Busch C, Schriek G, Metzger M, Just L, Drews U. Non-malignant migration of B16 mouse melanoma cells in the neural crest and invasive growth in the eye cup of the chick embryo. Melanoma Res. 2007;17(1):17–30. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3280114f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne NJ, Begbie J, Chilton JK, Schmidt H, Eickholt BJ. Semaphorin/neuroplin signaling influences the positioning of migratory neural crest cells within the hindbrain region of the chick. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:939–949. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postovit LM, Seftor EA, Seftor REB, Hendrix MJC. Influence of the microenvironment on melanoma cell-fate determination and phenotype. Can Res. 2006;66:7833–7836. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postovit LM, Costa FF, Bischof JM, Seftor EA, Wen B, Seftor REB, Feinberg AP, Soares MB, Hendrix MJC. The commonality of plasticity underlying multipotent tumor cells and embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:908–917. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Seftor EA, Kirschmann DA, Lipavsky A, Wheaton WW, Abbott DE, Seftor REB, Hendrix MJC. Human embryonic stem cell microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of aggressive cancer cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800467105. In press.

- Raible DW, Wood A, Hodson W, Henion PD, Weston JA, Eisen JS. Segregation and early dispersal of neural crest cells in the embryonic zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1992;195:29–42. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001950104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real C, Glavieux-Paranaud C, LeDouarin NM, Dupin E. Clonally cultured differentiated pigment cells can dedifferentiate and generate multipotent progenitors with self-renewal potential. Dev Biol. 2006;300:656–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago A, Erickson CA. Ephrin-B ligands play a dual role in the control of neural crest cell migration. Dev. 2002;129:3621–3632. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M. Development and evolution of the migratory neural crest: a gene regulatory perspective. Curr Opinion in Genet and Dev. 2006;16:360–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling TF, Kimmel CB. Segment and cell type lineage restrictions during pharyngeal arch development in the zebrafish embryo. Dev. 1994;120:483–494. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriek G, Oppitz M, Busch C, Just L, Drews U. Human SK-Mel 28 melanoma cells resume neural crest cell migration after transplantation into the chick embryo. Melanoma Res. 2005;15(4):225–34. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbedzija GN, Bronner-Fraser M, Fraser SE. A vital dye analysis of the timing and pathways of avian trunk neural crest cell migration. Dev. 1989;106:809–816. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.4.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidani M, Wessels D, Mouneimne G, Ghosh M, Goswami S, Sarmiento C, Wang W, Kuhl S, El-Sibai M, Backer JM, Eddy R, Soll D, Condeelis J. Cofilin determines the migration behavior and turning frequency of metastatic cancer cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:777–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Robinson V, Patel K, Wilkinson DG. The EphA4 and EphB1 receptor tyrosine kinases and ephrin-B2 ligand regulate targeted migration of branchial neural crest cells. Curr Biol. 1997;7:561–570. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Graham A. Restricting Bmp-4 mediated apoptosis in hindbrain neural crest. Dev Dyn. 2001;220(3):276–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(20010301)220:3<276::AID-DVDY1110>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneyhill L, Bronner-Fraser M. Recycling signals in the neural crest. J Biol. 2005;4(3):10. doi: 10.1186/jbiol31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S, Kasuya Y, Shimizu M, Matsuura T, Tsuboi M, Kawakami A, Fujisawa H. Expression of a cell adhesion molecule, neuropilin, in the developing chick nervous system. Dev Biol. 1995;170:207–222. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of plutipotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Kuo C, Mortin DL, Wang HJ, Hoon DS. Expression of differentiation melanoma-associated antigen genes is associated with favorable disease outcome in advanced-stage melanomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickle C, Trinkaus JP. Observations on nudging cells in culture. Nature. 1976;261:413. doi: 10.1038/261413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topczewska JM, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Sam A, Hess AR, Wheaton WW, Nickoloff BJ, Topczewski J, Hendrix MJ. Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal signaling: role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nat Med. 2006;12:925–932. doi: 10.1038/nm1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor PA, Krumlauf R. Patterning the cranial neural crest: hindbrain segmentation and Hox gene plasticity. Nat Rev Neuro. 2000;1:116–124. doi: 10.1038/35039056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor PA, Sobieszczuk D, Wilkinson D, Krumlauf R. Signaling between the hindbrain and paraxial tissues dictates neural crest migration pathways. Dev. 2002;129:433–443. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsarovina K, Schellenergerm J, Schneider C, Rohrer H. Progenitor cell maintenance and neurogenesis in sympathetic ganglia involves Notch signaling. Mol Cell Neuro. 2008;37:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HU, Anderson DJ. Eph family transmembrane ligands can mediate repulsive guidance of trunk neural crest cell migration and motor axon outgrowth. Neuron. 1997;18(3):383–96. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff JB, Wang Y, Lin EY, Li JF, Goswami S, Stanley ER, Segall JE, Pollard JW, Condeelis J. Direct visualization of machrophage-assisted tumor cell intravasation in mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2649–2656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang R, Davalos AR, Hensel CH, Zhou XJ, Tse C, Naylor SL. Semaphorin 3F gene from human 3p21.3 suppresses tumor formation in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62(9):2637–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HM, Bergner AJ, Anderson RB, Enomoto H, Milbrandt J, Newgreen DF, Whitington PM. Dynamics of neural crest-derived cell migration in the embryonic mouse gut. Dev Biol. 2004;270:455–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HH, Moens CB. Semaphorin signaling guides cranial neural crest cell migration in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2005;280:373–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, France JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]