Abstract

Nitrilase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 33278 hydrolyses both aliphatic and aromatic nitriles. Replacing Tyr-142 in the wild-type enzyme with the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine did not alter specificity for either substrate. However, the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic amino acids (alanine, valine and leucine) at position 142 were specific only for aromatic substrates such as benzonitrile, m-tolunitrile and 2-cyanopyridine, and not for aliphatic substrates. These results suggest that the hydrolysis of substrates probably involves the conjugated π-electron system of the aromatic ring of substrate or Tyr-142 as an electron acceptor. Moreover, the mutants containing charged amino acids such as aspartate, glutamate, arginine and asparagine at position 142 displayed no activity towards any nitrile, possibly owing to the disruption of hydrophobic interactions with substrates. Thus aromaticity of substrate or amino acid at position 142 in R. rhodochrous nitrilase is required for enzyme activity.

Keywords: aliphatic nitrile, aromatic nitrile, nitrilase, Rhodococcus rhodochrous, substrate specificity

Abbreviations: LB, Luria–Bertani

INTRODUCTION

Nitrilases are enzymes widely expressed in prokaryotes and eukaryotes that hydrolyse non-peptide carbon–nitrogen bonds [1]. They are important industrial enzymes used to convert nitriles directly into corresponding acids and ammonia [2]. Nitrilases have attracted interest as a valuable alternative to chemical hydrolysis in organic chemical processes because of their mild reaction conditions and reduced output of environmental pollution. Previous studies have reported the occurrence, applicability and action mechanism of nitrilases, and the cloning of the nitrilase genes from Alcaligenes faecalis JM3, Arabidopsis thaliana, Brassica napus, Gordona terrae MA-1, Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae, Rhodococcus rhodochrous K22 and R. rhodochrous J1 [1,3–5]. Nitrilases have different substrate specificities, making them useful for the hydrolysis of a large number of nitriles [5]. Nitrilases have been classified into three major categories on the basis of substrate specificity, although some nitrilases exhibit broad substrate specificity. Aromatic nitrilases act on aromatic or heterocyclic nitriles, aliphatic nitrilases act on aliphatic nitriles, and arylacetonitrilases act on arylacetonitriles [5,6].

The catalytic triad Cys-Glu-Lys is conserved in all members of the nitrilase superfamily [1,4,7–9], and there are currently no crystal structures available for nitrilases, but there are for other members of the nitrilase superfamily: N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase from Agrobacterium [10], nitrilase–fragile histidine triad fusion protein (Nitfhit Rosetta Stone protein) from Caenorhabditis elegans [11] and a homologous protein of unknown function from Saccharomyces cerevisiae [12]. A recent article on molecular modelling of nitrilase [13] described interactions between the structural subunits of nitrilase, but did not provide details about its active site. In spite of many studies on substrate specificity of nitrilases, the mechanism of substrate specificity has not been elucidated using structural and mutational analysis, except for study of the substrate specificity of arylacetonitrilase [14].

In the present paper, we performed sequence alignment, mutational analysis and molecular modelling of nitrilase in order to find a determinant residue for the substrate specificity of nitrilase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 33278. Our results demonstrate that aromaticity of the amino acid at position 142 is required for reaction with aliphatic substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The kits for PCR product purification, gel extraction and plasmid preparation, as well as the DNA-modifying enzymes, were purchased from Promega. The aromatic nitriles (benzonitrile, m-tolunitrile and 2-cyanopyridine) and aliphatic nitriles (adiponitrile, glutaronitrile, sebaconitrile and succinonitrile) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company.

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 33278, Escherichia coli ER2566, and the plasmid pET-28a (+) (Novagen) were used as a source of genomic DNA of nitrilase, host cells and expression vector respectively. R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 was grown aerobically at 26 °C in yeast malt extract broth (1.0% glucose, 0.5% peptone, 0.3% yeast extract and 0.3% malt extract). The recombinant E. coli for expression of the enzyme was cultivated in 500 ml of LB (Luria–Bertani) medium (1.0% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract and 1.0% NaCl) in a 2 litre flask containing 20 μg/ml kanamycin at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rev./min. When the D600 of the culture reached 0.6, IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside) was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM to induce nitrilase expression, and the culture was incubated at 16 °C for 16 h.

Gene cloning and site-directed mutagenesis of nitrilase

The nitrilase gene was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 as a template. Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for gene cloning were designed using the published DNA sequence for nitrilase from R. rhodochrous J1 (GenBank® accession number D11 425). Forward (5′-TTCATATGGTCGAATACACAAAC-3′) and reverse (5′-TTAAGCTTTCAGATGGAGGCTG-3′) primers were designed for introduction of the underlined NdeI and HindIII restriction sites respectively. The amplified DNA fragment was purified using a Promega PCR purification kit and was ligated into the NdeI and HindIII sites of pET-28a(+). The resulting plasmid was used to transform the E. coli ER2566 strain. E. coli cells containing the plasmid were grown on LB medium. The expression of the gene encoding nitrilase was determined by both SDS/PAGE (12% gels) and the assay of enzyme activity. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the overlap extension PCR method [15].

Purification of nitrilase

The recombinant cells were harvested from the culture broth by centrifugation at 6000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, washed twice with 0.85% NaCl and then resuspended in buffer A composed of 50 mM sodium monophosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole and 0.1 mM PMSF as protease inhibitors. The resuspended cells were disrupted by ultrasonication (Fisher Scientific) on ice. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 13000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm pore-size filter. The filtrate was applied to HisTrap HP chromatography column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A. The bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient between 10 and 250 mM imidazole in buffer A. The active fraction was dialysed at 4 °C for 24 h against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and the resulting solution was used as purified enzyme. All purification steps using columns were carried out with an FPLC system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in a cold room. The protein concentration was quantified by the Bradford method [16]. The purified proteins were confirmed by SDS/PAGE (12% gels).

Determination of molecular mass

The subunit molecular mass of nitrilase were examined by SDS/PAGE (12% gels) under denaturing conditions, using the proteins of a pre-stained ladder (MBI Fermentas) as reference proteins. All protein bands were stained with Coomassie Blue for visualization. The molecular mass of the native enzyme was determined by gel-filtration chromatography on a Sephacryl S-300 preparative-grade column HR 16/60 (GE Healthcare). The purified enzyme was activated by adding benzonitrile as substrate for 24 h. The enzyme solution was applied to the column and eluted with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 150 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The column was calibrated with thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and conalbumin (75 kDa) as reference proteins (GE Healthcare) and the molecular mass of the native enzyme was calculated by comparing with the migration length of reference proteins.

Measurement of activity and determination of kinetic parameters of wild-type and mutant enzymes

The activity of nitrilase was measured by assaying the release of ammonia as described previously [17,18]. The specific activity was determined after the enzymatic reaction was performed in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM substrate and 10% (v/v) methanol at 25 °C for 20 min. In the kinetic study, various amounts of nitriles (0.1–0.5 mM) were incubated in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing nitrilase enzyme and 10% (v/v) methanol at 25 °C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by adding HCl to the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 200 mM. The kinetic parameters were determined by fitting the data to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

Modelling

The three-dimensional structure of R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 nitrilase was generated using the Accelrys Discovery Studio Modeler [19]. The aim of our comparative modelling was to generate the most probable structure of the query protein through alignment with template sequences that simultaneously satisfied spatial restraints and local molecular geometry. A BLAST search of the Protein Databank demonstrated strongest similarity between R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 nitrilase and two N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase PDB entries, 1ERZ and 1FO6. These similar proteins were used as templates for modelling, after alignment with the ClustalW program [20]. The structure generated was improved further by refinement of the loop conformations by assessing the compatibility of their amino acid sequences with known PDB structures using the Protein Health module in Discovery Studio. All simulation experiments were carried out using a HP XW6200 Workstation with dual Intel Xeon 3.2 GHz processors.

Nitriles were docked in the models of wild-type and mutant nitrilases using the Surflex docking program (Tripos) [21]. The active site was defined as a collection of amino acid residues enclosed within a sphere of 4.5 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) radius centred on the catalytic triad [11]. Each docking run consisted of 100 independent docks with 1000 iteration cycles. A random start was used to generate the substrate position within the docking box. The substrate orientation giving the lowest interaction energy was chosen for additional rounds of docking.

RESULTS

Cloning and molecular mass of nitrilase

The nitrilase gene was obtained from chromosomal DNA of R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 using primers designed from the published genomic DNA sequence of R. rhodochrous J1 (GenBank® accession number D11 425). The cloned nitrilase gene contained a sequence of 1101 bp encoding a 366-amino-acid protein and was the same as that of the published R. rhodochrous tg1-A6 sequence (GenBank® accession number EF467367).

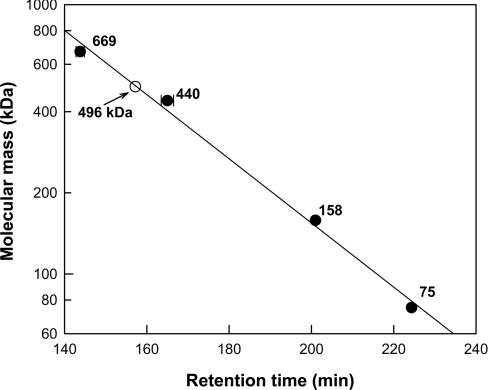

The subunit molecular masses of the purified wild-type and mutant enzymes in SDS/PAGE were approx. 40 kDa. They were similar to the calculated value of 41338 Da based on the 366-residue protein and six histidine residues, as determined with the Compute pI/Mw tool [22]. After the purified enzyme was activated by adding benzonitrile as substrate for 24 h, the active form of the enzyme with substrate eluted as a peak between ferritin (440 kDa) and thyroglobulin (669 kDa), corresponding to a molecular mass of 496 kDa (Figure 1). These results indicate that the enzyme migrates as a dodecamer in gel filtration and thus may also be active as a dodecamer in solution.

Figure 1. Determination of molecular mass of nitrilase from R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 by gel-filtration chromatography.

The reference proteins were thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa) and conalbumin (75 kDa). Nitrilase eluted at a position corresponding to 497 kDa. Results are means±S.D. for three experiments.

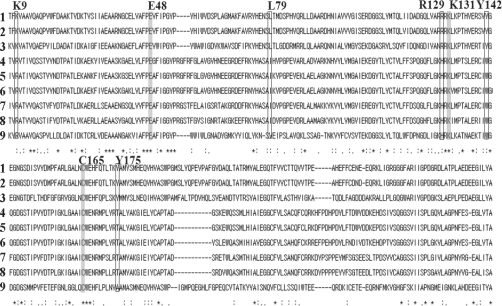

Selection of the individually conserved residues for aliphatic and aromatic nitriles by sequence alignment

Sequence data for the nitrilases were obtained using the ExPASy proteomics server. Sequence alignment was performed with aliphatic nitrilases (EC 3.5.5.7) of R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278, J1 and K22, with aromatic nitrilases (EC 3.5.5.1) from A. thaliana (NIT1, NIT2, NIT3 and NIT4), Nicotiana tabacum (NIT4), and Bacillus sp., and with N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase from Agrobacterium as a template for modelling using the ClustalW program (Figure 2). All nitrilases displayed a conserved catalytic triad consisting of Glu-48, Cys-165 and Lys-131 of R. rhodochrous J1, as well as the individually conserved amino acid residues Lys-9, Leu-79, Arg-129, Tyr-142 and Tyr-175 for aliphatic and aromatic nitrilases. These conserved residues were selected as candidate determinant residues for substrate specificity for aliphatic and aromatic nitriles.

Figure 2. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of aliphatic and aromatic nitrilases, and a template enzyme for modelling.

Aliphatic nitrilases: (1) nitrilase from R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278, (2) J1, (3) K22. Aromatic nitrilases: (4) NIT1, (5) NIT2, (6) NIT3, (7) NIT4 from A. thaliana, (8) NIT4 from N. tabacum, (9) nitrilase from Bacillus sp., (10) N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase from Agrobacterium (a template for modelling). The conserved active-site residues (catalytic triad) are highlighted in grey, and the individually conserved residues for aromatic and aliphatic nitriles are highlighted with a box and are labelled using the single-letter code.

Alanine substitutions of the individually conserved residues for aliphatic and aromatic nitriles and the catalytic triad

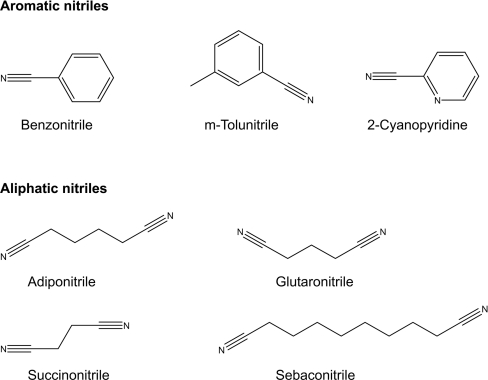

The aromatic nitrile substrates benzonitrile, m-tolunitrile and 2-cyanopyridine were selected on the basis of their functional group, and the aliphatic nitriles adiponitrile, glutaronitrile, sebaconitrile and succinonitrile were chosen on the basis of their side-chain carbon number. The chemical structures of the substrates are shown in Figure 3. Each individually conserved residue and the catalytic triad were sequentially replaced with alanine to produce nitrilase mutants. Enzyme activities towards the aromatic and aliphatic nitrile substrates were determined for the alanine-substituted mutants and were compared with those of wild-type nitrilase. The mutants with an alanine-replaced catalytic triad exhibited no activity towards any nitrile. Activities towards aromatic and/or aliphatic nitriles were displayed by the wild-type enzyme and all of the alanine-substituted mutant enzymes, with the exception of R129A. The kinetic parameters of the wild-type enzyme and the K9A, L20A and Y142A mutant enzymes are shown in Table 1, but the kinetic parameters of the Y175A mutant enzyme are not shown owing to low activity (less than ∼6 μmol/min per mg). The alanine substitution at position 129 completely abolished enzymatic activity towards all nitriles. Among various amino acids, only the positively charged amino acids (arginine, lysine or histidine) at position 129 had activity. We are currently investigating the role of positively charged amino acids at position 129. The Y142A mutant hydrolysed aromatic, but not aliphatic nitriles, indicating that the amino acid at position 142 might be crucial for determining substrate specificity.

Figure 3. Chemical structures of aromatic and aliphatic nitriles as substrates of wild-type and mutant enzymes.

Table 1. Kinetic parameters of wild-type and alanine-substituted mutant enzymes of the individually conserved residues for aliphatic and aromatic nitrilases.

The kcat values were calculated by considering the enzyme as a dodecameric form. Results are means±S.D. for five experiments. –, no activity in the method used.

| Substrate | Enzyme | Km (μM) | kcat (min−1 ×10−4) | kcat/Km (min−1·M−1 ×10−2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic nitriles | Benzonitrile | Wild-type | 1070±10 | 94±1 | 880±20 |

| K9A | 1020±10 | 94±4 | 920±50 | ||

| L79A | 910±20 | 126±2 | 1380±50 | ||

| Y142A | 1580±150 | 173±8 | 1090±150 | ||

| m-Tolunitrile | Wild-type | 1850±140 | 143±12 | 770±120 | |

| K9A | 1620±20 | 105±3 | 650±30 | ||

| L79A | 1790±10 | 166±2 | 930±20 | ||

| Y142A | 612±10 | 113±6 | 1850±130 | ||

| 2-Cyanopyridine | Wild-type | 1530±30 | 106±1 | 690±20 | |

| K9A | 1250±10 | 113±3 | 900±30 | ||

| L79A | 1500±20 | 151±6 | 1010±50 | ||

| Y142A | 819±10 | 185±1 | 2260±40 | ||

| Aliphatic nitriles | Glutaronitrile | Wild-type | 1240±50 | 173±3 | 1400±80 |

| K9A | 1190±10 | 196±2 | 1650±30 | ||

| L79A | 1150±20 | 189±3 | 1630±50 | ||

| Y142A | – | – | – | ||

| Adiponitrile | Wild-type | 933±100 | 276±24 | 2960±570 | |

| K9A | 851±20 | 343±3 | 4040±130 | ||

| L79A | 921±10 | 298±3 | 3240±70 | ||

| Y142A | – | – | – |

Site-directed mutagenesis at position 142

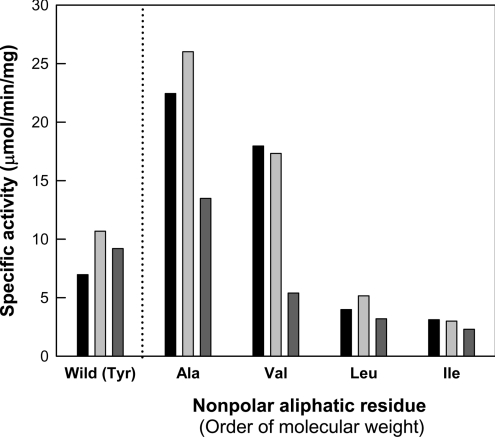

The tyrosine residue at position 142 of the nitrilase enzyme was replaced with respective non-polar aliphatic amino acids, including glycine, alanine, valine, leucine and isoleucine. Although they exhibited no activity towards any of the tested aliphatic nitriles, all of the mutant enzymes, except the glycinesubstituted mutant, displayed activities towards aromatic substrates, including benzonitrile, m-tolunitrile and 2-cyanopyridine (Figure 4). The less hydrophobic 2-cyanopyridine (having a nitrogen atom on its ring) was a poorer substrate for the nitrilase. Thus the enzymatic reaction of nitrilase probably involves hydrophobic interactions between the enzyme and a substrate. Among the mutants, the Y142A mutant showed the highest activity towards aromatic substrates. As the molecular size of the non-polar aliphatic amino acid side chain increased, the activities of the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic residues, except glycine, towards aromatic substrates decreased. The far-UV CD spectra of the Y142G mutant and the wild-type enzyme were similar (results not shown); nevertheless, this mutant, which contained the smallest residue (glycine), showed no activity.

Figure 4. Specific activities of wild-type and mutant enzymes at position 142 containing non-polar aliphatic amino acids for aromatic nitriles such as benzonitrile (black bars), m-tolunitrile (light-grey bars) and 2-cynanopyridine (dark-grey bars).

When Tyr-142 was replaced with a charged polar amino acid such as asparagine, arginine, aspartate or glutamate, the mutants exhibited no activity towards any tested substrate. The Y142S mutant, however, displayed activity towards aromatic, but not aliphatic, nitriles, showing substrate specificity similar to that of the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic amino acids. When Tyr-142 was replaced with the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine, the mutant retained activity towards both aromatic and aliphatic nitriles.

Kinetic analysis of wild-type and mutant enzymes

The kinetic parameters of the purified wild-type and mutant enzymes at position 142 were determined for the hydrolysis of aromatic and aliphatic substrates (Table 2). The kinetic parameters of the wild-type and mutant enzymes for the hydrolysis of succinonitrile and sebaconitrile, and the Y142L and Y142I mutants for aromatic nitriles were not determined because of their low specific activities (less than ∼6 μmol/min per mg). Among the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic residues at position 142, the Y142A mutant showed the highest kcat (or kcat/Km) values for aromatic nitriles such as benzonitrile, m-tolunitrile and 2-cyanopyridine. Compared with the wild-type enzyme, the Y142A and Y142S mutants exhibited slightly higher kcat/Km values for aromatic nitriles, but they showed no activity towards aliphatic nitriles. The Y142F mutant showed slightly lower kcat/Km values for aromatic and aliphatic nitriles, compared with the wild-type enzyme.

Table 2. Kinetic parameters of wild-type and mutant enzymes at position 142.

The kcat values were calculated by considering the enzyme as a dodecameric form. Results are means±S.D. for five experiments. Low, not determined due to low activity (less than ∼6 μmol/min per mg); –, no activity in the method used.

| Substrate | Residue | Km (μM) | kcat (min−1 ×10−4) | kcat/Km (min−1 M−1 ×10−2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic nitriles | Benzonitrile | Tyrosine (wild-type) | 1070±10 | 94±1 | 880±20 |

| Phenylalanine | 3450±190 | 149±7 | 430±40 | ||

| Serine | 1820±100 | 258±11 | 1420±140 | ||

| Glycine | – | – | – | ||

| Alanine | 1580±150 | 173±8 | 1090±150 | ||

| Valine | 490±30 | 83±2 | 1690±140 | ||

| Leucine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Isoleucine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| m-Tolunitrile | Tyrosine (wild-type) | 1850±140 | 143±12 | 770±120 | |

| Phenylalanine | 1190±30 | 85±2 | 710±30 | ||

| Serine | 1490±110 | 226±13 | 1520±200 | ||

| Glycine | – | – | – | ||

| Alanine | 612±10 | 113±6 | 1850±130 | ||

| Valine | 470±30 | 61±1 | 1300±100 | ||

| Leucine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Isoleucine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| 2-Cyanopyridine | Tyrosine (wild-type) | 1530±30 | 106±1 | 690±20 | |

| Phenylalanine | 1560±30 | 71±1 | 460±20 | ||

| Serine | 3750±60 | 440±22 | 1170±80 | ||

| Glycine | – | – | – | ||

| Alanine | 819±10 | 185±1 | 2260±40 | ||

| Valine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Leucine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Isoleucine | Low | Low | Low | ||

| Aliphatic nitriles | Glutaronitrile | Tyrosine (wild-type) | 1240±50 | 173±3 | 1400±80 |

| Phenylalanine | 1560±30 | 106±1 | 680±20 | ||

| Serine | – | – | – | ||

| Glycine | – | – | – | ||

| Alanine | – | – | – | ||

| Valine | – | – | – | ||

| Leucine | – | – | – | ||

| Isoleucine | – | – | – | ||

| Adiponitrile | Tyrosine (wild-type) | 933±100 | 276±24 | 2960±570 | |

| Phenylalanine | 688±10 | 106±1 | 1540±40 | ||

| Serine | – | – | – | ||

| Glycine | – | – | – | ||

| Alanine | – | – | – | ||

| Valine | – | – | – | ||

| Leucine | – | – | – | ||

| Isoleucine | – | – | – |

DISCUSSION

A homology model of nitrilase from R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 was constructed based on the crystal structure of templates of two N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase PDB entries (1ERZ and 1FO6). Although the level of sequence identity between nitrilase and template was relatively low (∼15.3% identity and 38.6% similarity), the catalytic triads (Glu-48, Cys-165 and Lys-131) of R. rhodochrous nitrilase and the N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase of the same nitrilase superfamily were completely conserved as shown in Figure 2. The alanine substitution of the catalytic triad of R. rhodochrous nitrilase exhibited no activity towards any nitrile (Table 1), suggesting that the catalytic triad was involved in the active site. Moreover, the activities of the mutants at position 142 for various substrates indicated that the position was closely related to substrate specificity. Thus the active-site structure of the homology model, including the catalytic triad and position 142, can be used in docking studies.

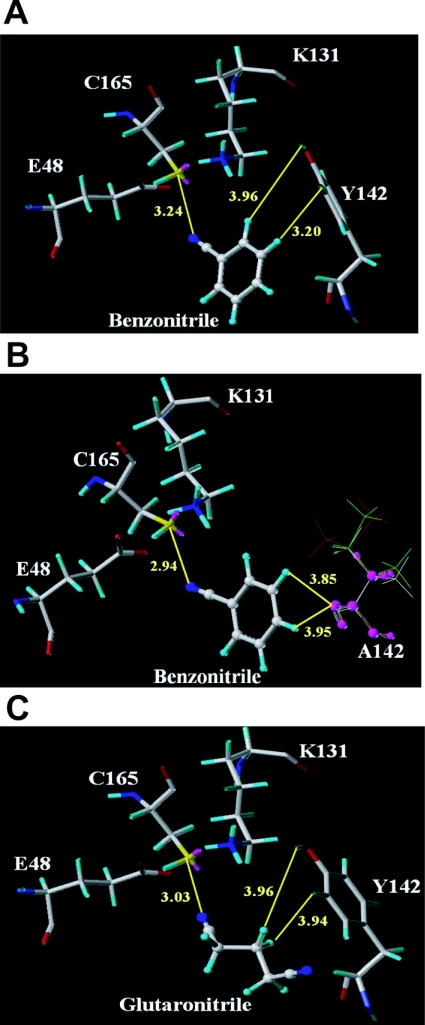

The molecular docking studies of R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 nitrilase show substrate interactions in the active site. In the catalytic triad, Cys-165 attacks the cyano group of nitriles as a nucleophile, Glu-48 assumes the role of a general base, and Lys-131 is involved in stabilization of a tetrahedral intermediate structure [10]. Position 142 is located at one side of the catalytic triad (Figure 5). When the aromatic benzonitrile was docked in the active site, the wild-type nitrilase showed a slightly longer distance between the cyano group of benzonitrile and the sulfur of Cys (3.24 Å), compared with that of the Y142A mutant (2.94 Å) (Figures 5A and 5B). The distances seem to explain the slightly higher kcat values of the Y142A mutant for aromatic substrates. The order of the specific activities of the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic residues was Y142A>Y142V>Y142L>Y142I, in increasing order of side-chain size (Figure 5). Thus an increase in the size of the side chain on the amino acid at position 142 caused a decrease in the kcat values of the mutants for aromatic nitriles. This may result from increased steric hindrance between the aromatic substrate and the aliphatic residue owing to the increased side-chain size. The model in Figure 5(B) shows that the steric hindrance with each respective mutant correlates with the increase in the size of the non-polar aliphatic residue at position 142. In the active site of the wild-type enzyme, the distance between glutaronitrile, which is an aliphatic substrate, and cysteine (3.03 Å) was shorter than that between benzonitrile and cysteine (3.24 Å) (Figures 5A and 5C). This difference in distance may explain the slightly higher kcat for glutaronitrile than for benzonitrile of the wild-type enzyme. However, obtaining structures of the enzyme in complex with these substrates would be necessary to provide further evidence for this conclusion.

Figure 5. Model of the active site with bound substrate.

(A) Docking of benzonitrile into the active site of wild-type enzyme. (B) Docking of benzonitrile into the active site of mutant enzyme at position 142 containing non-polar aliphatic amino acids. The non-polar aliphatic amino acids are alanine (purple), valine (white), leucine (green) and isoleucine (red) at position 142. (C) Docking of glutaronitrile into the active site of wild-type enzyme.

The wild-type enzyme exhibited activity towards both classes of aromatic and aliphatic substrates, whereas the mutants containing a non-polar aliphatic residue at position 142 and the Y142S mutant had activities towards aromatic, but not aliphatic, substrates. The loss of specificity for aliphatic nitriles in the mutant enzymes suggests that the aromatic side-chain on the residue at position 142 is important for nitrilase hydrolysis of aliphatic substrates. When Tyr-142 was replaced with phenylalanine, the resultant Y142F mutant retained activities towards both aromatic and aliphatic nitrile substrates, with substrate specificity similar to that of the wild-type enzyme. This suggests that the aromatic rings of tyrosine and phenylanine at position 142 are involved in nitrilase-catalysed binding and electron transfer for aliphatic substrates. This phenomenon can be explained by electron transfer between enzyme and substrate via a conjugated system [23]. We propose that the conjugated π-electron system of the aromatic substrate serves as an electron acceptor, whereas the aliphatic substrate has no conjugated system. As a result, the mutants containing aliphatic residues at position 142 had no activity towards aliphatic substrates owing to their lack of an aromatic ring to provide an electron acceptor. This reinforces our hypothesis further that an aromatic ring at position 142 is used as an electron acceptor during the catalytic reaction between nitrilase and aliphatic nitriles.

The mutants containing charged amino acids such as aspartate, glutamate, arginine and asparagine at position 142 showed no activity towards any substrate, probably because the charged amino acids disrupt hydrophobic interactions with the substrate. These results indicate the importance of hydrophobic interactions in the recognition of nitrile substrates. The glycine residue at position 142 would not be suitable for hydrophobic interaction with any substrate, and, consequently, the Y142G mutant displayed no activity towards aromatic or aliphatic substrates. To confirm our molecular modelling and structural analyses, the crystal structure of nitrilase should be determined.

In the present study, the amino acid at position 142 of nitrilase derived from R. rhodochrous ATCC 33278 was identified as a determinant residue of substrate specificity based on the following results: (i) the mutants containing aromatic amino acids retained activity towards both aliphatic and aromatic nitriles; (ii) the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic amino acids showed activity towards aromatic, but not aliphatic, nitriles; (iii) for the mutants containing non-polar aliphatic residues, the activity towards aromatic substrates decreased with increasing size of the amino acid side chain; and (iv) the mutants containing charged amino acids had no activity towards any nitrile. These data enable a more detailed understanding of the roles of selected active site residues in the catalytic process of the R. rhodochrous nitrilase.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (KRF-2006-D00087) from the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government [MOEHRD (Ministry of Education and Human Resource Development)] and partially supported by the Institute of Biomedical Science and Technology, Konkuk University.

References

- 1.Pace H. C., Brenner C. The nitrilase superfamily: classification, structure and function. Genome Biol. 2001;2:1–9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-1-reviews0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagasawa T., Yamada H. Microbial transformations of nitriles. Trends Biotechnol. 1989;7:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner C. Catalysis in the nitrilase superfamily. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:775–782. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Reilly C., Turner P. D. The nitrilase family of CN hydrolysing enzymes a comparative study. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;95:1161–1174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee A., Sharma R., Banerjee U. C. The nitrile-degrading enzymes: current status and future prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;60:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi M., Shimizu S. Versatile nitrilases: nitrile-hydrolysing enzymes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994;120:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C. Y., Chiu W. C., Liu J. S., Hsu W. H., Wang W. C. Structural basis for catalysis and substrate specificity of Agrobacterium radiobacter N-carbamoyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26194–26201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson D. E., Feng R., Dumas F., Groleau D., Mihoc A., Storer A. C. Mechanistic and structural studies on Rhodococcus ATCC 39484 nitrilase. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 1992;15:283–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson D. E., Feng R., Storer A. C. Detection of covalent enzyme–substrate complexes of nitrilase by ion-spray mass spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1990;277:112–114. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80821-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakai T., Hasegawa T., Yamashita E., Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., Ueki T., Nanba H., Ikenaka Y., Takahashi S., Sato M., Tsukihara T. Crystal structure of N-carbamyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase with a novel catalytic framework common to amidohydrolases. Structure. 2000;8:729–737. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pace H. C., Hodawadekar S. C., Draganescu A., Huang J., Bieganowski P., Pekarsky Y., Croce C. M., Brenner C. Crystal structure of the worm NitFhit Rosetta Stone protein reveals a Nit tetramer binding two Fhit dimers. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:907–917. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumaran D., Eswaramoorthy S., Gerchman S. E., Kycia H., Studier F. W., Swaminathan S. Crystal structure of a putative CN hydrolase from yeast. Proteins. 2003;52:283–291. doi: 10.1002/prot.10417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thuku R. N., Weber B. W., Varsani A., Sewell B. T. Post-translational cleavage of recombinantly expressed nitrilase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 yields a stable, active helical form. FEBS J. 2007;274:2099–2108. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiziak C., Klein J., Stolz A. Influence of different carboxy-terminal mutations on the substrate-, reaction- and enantiospecificity of the arylacetonitrilase from Pseudomonas fluorescens EBC191. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2007;20:385–396. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chockalingam K., Chen Z., Katzenellenbogen J. A., Zhao H. Directed evolution of specific receptor–ligand pairs for use in the creation of gene switches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:5691–5696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409206102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M., Nagasawa T., Yamada H. Nitrilase of Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1: purification and characterization. Eur. J. Biochem. 1989;182:349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fawcett J. K., Scott J. E. A rapid and precise method for the determination of urea. J. Clin. Pathol. 1960;13:156–159. doi: 10.1136/jcp.13.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sali A., Blundell T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain A. N. Surflex: fully automatic flexible molecular docking using a molecular similarity-based search engine. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:499–511. doi: 10.1021/jm020406h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkins M. R., Gasteiger E., Bairoch A., Sanchez J. C., Williams K. L., Appel R. D., Hochstrasser D. F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999;112:531–552. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babbitt P. C., Gerlt J. A. Understanding enzyme superfamilies. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:30591–30594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]