Abstract

This study was to determine whether the proportion of death due to breast cancer changed over time in different cohorts of women diagnosed with breast cancer. We identified 316,149 women with breast cancer at age 20 or older during 1975–2003 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results 9 tumor registries in the United States. Logistic regression models were used to assess the effects of time period on the likelihood of dying because of breast cancer as underlying cause of death, adjusting for other factors. Overall, underlying cause of death was 52.8% due to breast cancer, 17.8% due to heart disease, and 4.9% due to stroke. Percentage of death due to breast cancer did not change significantly from 1975 to 2003 in those who died <12 months after diagnosis, but decreased significantly in women who died between 1 and 15 years. Risk of death due to breast cancer in women diagnosed during 1995–1998 was significantly lower than those in 1975–1979 (odds ratio = 0.79, 95% confidence interval = 0.70 – 0.89), after adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, and tumor stage. Percentage of death due to breast cancer decreased significantly with age from 87.5% in women <40% to 30.7% in those 80 or older, which was not significantly affected by year of diagnosis. Proportion of death due to breast cancer increased with advanced tumor stage and was similar in various racial/ethnic groups of population. The findings demonstrated that the impact of breast cancer on overall death was reduced after 1 year of diagnosis, but suggested the need for continued cancer surveillance.

Keywords: breast cancer, cause of death, women, SEER, tumor registry, temporal trend

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in women.1–4 According to the American Cancer Society data, it was estimated that 212,920 women will be diagnosed with and 40,970 women will die of breast cancer in 2006.3 During the past decade, mortality for patients with breast cancer decreased significantly,1 largely because of early detection or screening for breast cancer and advances in medical care and treatments.5–17 As a result, many patients with breast cancer can live much longer than ever before, and many of these women will die of causes other than breast cancer when they are getting older. However, there is little information on how the main underlying causes of death changed over time during the past several decades for women with breast cancer, although several studies have examined competing causes of death for women with breast cancer and found that other causes of death increased with age.18–22 Schairer et al found that the probability of death from breast cancer relative to the probability of death from other causes declined with age.22 However, it is unknown if the proportion of death from breast cancer relative to other causes changed over time in different cohorts of women diagnosed with breast cancer from 1975 to 2003. This study used data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registries, one of the most often referred data sources on cancer, to examine the causes of death for women diagnosed with breast cancer from 1975 to 2003, to determine the percentage of women who died of breast cancer and percentages of women who died of heart disease, stroke, pneumonia, or other causes, and to determine how the competing causes of death changed over time. With improvement in medical care and early diagnosis for this disease in recent decades, the postdiagnosis life span increased substantially.1–4,9–17 Hence, women with breast cancer may have been subject to other competing risks of death for a longer period of time, which would result in a relatively lower proportion of deaths due to breast cancer in recent years compared with earlier cohorts.18–22 On the basis of evidence from previous randomized trials9–17 and observational studies,18–22 it would be reasonable to hypothesize that the majority of women with breast cancer died of causes other than breast cancer and that the proportion of women whose underlying cause of death was breast cancer decreased over time from 1975 to 2003.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Sources

Data used in this article were from the SEER 1975–2003 Public Use Data Set (CD-ROM) released in April 2006.23 The SEER program supports the 9 population-based tumor registries in 4 metropolitan areas (San Francisco/Oakland, Detroit, Atlanta, Seattle) and 5 states (Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah, and Hawaii) since 1975, covering over 14% of the US population.1 The registries ascertain all newly diagnosed (incident) breast cancer cases from multiple reporting sources such as hospitals, outpatient clinics, laboratories, private medical practitioners, nursing/convalescent homes/hospices, autopsy reports, and death certificates. Information in the data set includes tumor location and demographic characteristics such as age, gender, race, and marital status. The SEER public use data set also includes information on the types of surgical procedures and radiation therapy received. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston approved this study.

Study Population

We identified 316,149 women who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer at all ages between 1975 and 2003 in 9 SEER areas, in whom breast cancer was the first and only primary tumor. By the date of last follow-up (December 31, 2003), 136,450 (43.2%) patients died, of whom 72,064 (52.8%) died of breast cancer.

Study Variables

Causes of Death

The SEER data set provided the underlying cause of death for women with breast cancer who died. The leading causes of death included breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, other cancers, other cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and other causes. About 3.7% of cases had missing or unknown information on the causes of death.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

Other variables examined in the analysis included age at diagnosis (<44, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, ≥80 years), race (white, African American, American Indian, Asian, or unknown), Hispanic ethnicity (yes or no), tumor stage (local, regional, distant stage, or unstaged), year of diagnosis (1975–2003), and geographic area (9 SEER regions).23 Variables on tumor size, grade, and hormone receptor status, which were available since 1988, were also adjusted in the analysis.

Treatment for Breast Cancer

Breast-conserving surgery (BCS) was defined as receiving segmental mastectomy, lumpectomy, quadrantectomy, tylectomy, wedge resection, nipple resection, excisional biopsy, or partial mastectomy unspecified (SEER surgery codes 10–29).23 Mastectomy was defined as subcutaneous, total (simple), modified radical, radical, or extended radical mastectomy (codes 30–70).23 Radiation therapy included beam radiation, radioactive implants, brachytherapy, radioisotopes, or other radiation. Clinical guidelines recommend that patients with invasive breast cancer receive mastectomy or receive BCS followed by subsequent radiation therapy.24 The “no cancer-directed surgery” included either no surgical procedures, or only incisional, needle, or aspiration biopsy.24 Therefore, patients were categorized into 4 groups: no cancer-directed surgery (codes 0-9), BCS only without radiation therapy, BCS with radiation therapy, and mastectomy.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses generated the number of women diagnosed with breast cancer from 1975 to 2003 and the number and proportion of cases that died during these time periods, by patient and tumor characteristics, the year of diagnosis, and SEER region. The competing causes of death were stratified by the time period during which patients died. This was to ensure that comparisons were made among cases with a similar length of follow-up after diagnosis. A χ2 test of trend was used to assess the time trend of the proportion of death due to breast cancer in the 5 time periods. Logistic regression models were used to assess the effect of time period on the likelihood of dying because of breast cancer. In these multiple logistic regression analyses, odds ratios were adjusted for age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, and tumor stage. Logistic regression analyses were also performed to determine the effect of age and tumor stage on the competing cause of death while adjusting for the year of diagnosis. A simple linear regression was used to test the significance of odds ratio trend over time. All analytical procedures were performed using the SAS software package (Cary, NC)25 and Stata (version 9.2; College Station, TX).26

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the number of patients who were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer from 1975 to 2003 in the 9 SEER areas, the number of cases who died of all causes of death combined, and the number of cases who died of breast cancer only. Of 316,149 cases diagnosed with breast cancer, 43.2% died of all causes by the last date of follow-up, and 22.8% died of breast cancer specifically that accounted for 52.8% of all deaths. Mean age at diagnosis was 61 years. Over 75% of breast cancer cases occurred in women aged ≥50 and over 53% occurred in women aged ≥60. White women represented 86.1% of these cases, 8.0% were African Americans, and 5.2% were Asians. Over 96% of all breast cancer cases were non-Hispanic. The majority of breast cancer cases were diagnosed at localized stages (56.4%) or at regional stages (33.1%). Only 6.6% of women were diagnosed with advanced distant stage breast cancer. Of those who died of breast cancer as the underlying cause of death, 47% were regional stages, 24% were local stages, and 20.5% were distant stages. Those with distant stage who died of breast cancer as underlying cause of death accounted for 82.9% (14,803 of 17,854) of all deaths with distant stage. Most cases received mastectomy, and approximately 30% received BCS, but 8.6% of patients received BCS without radiation therapy.

TABLE 1.

Number of Patients Diagnosed With Breast Cancer and the Number of Deaths due to All Causes or Breast Cancer Only During 1975–2003

| Breast Cancer Cases (N = 316,149) |

All Causes of Death (N = 136,450) |

Breast Cancer Deaths (N = 72,064) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 36,129 | 11.4 | 28,883 | 21.2 | 15,099 | 21.0 |

| 1980–1984 | 40,852 | 12.9 | 29,828 | 21.9 | 15,753 | 21.9 |

| 1985–1989 | 51,183 | 16.2 | 30,305 | 22.2 | 15,291 | 21.2 |

| 1990–1994 | 58,299 | 18.4 | 24,894 | 18.2 | 12,810 | 17.8 |

| 1995–1999 | 69,119 | 21.9 | 17,280 | 12.7 | 9,829 | 13.6 |

| 2000–2003 | 60,567 | 19.2 | 5,260 | 3.9 | 3,282 | 4.6 |

| Age | ||||||

| <40 | 22,453 | 7.1 | 7,464 | 5.5 | 6,564 | 9.1 |

| 40–49 | 55,716 | 17.6 | 14,488 | 10.6 | 11,867 | 16.5 |

| 50–59 | 68,787 | 21.8 | 21,969 | 16.1 | 15,912 | 22.1 |

| 60–69 | 69,795 | 22.1 | 30,067 | 22.0 | 16,372 | 22.7 |

| 70–79 | 61,357 | 19.4 | 33,869 | 24.8 | 12,576 | 17.5 |

| 80+ | 38,041 | 12.0 | 28,593 | 21.0 | 8,773 | 12.2 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 272,117 | 86.1 | 119,008 | 87.2 | 61,256 | 85.0 |

| Black | 25,249 | 8.0 | 12,395 | 9.1 | 7,768 | 10.8 |

| Asian | 16,339 | 5.2 | 4,413 | 3.2 | 2,682 | 3.7 |

| American Indian | 1,077 | 0.3 | 417 | 0.3 | 276 | 0.4 |

| Missing | 1,367 | 0.4 | 217 | 0.2 | 82 | 0.1 |

| Hispanic origin | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 303,943 | 96.1 | 132,332 | 97.0 | 69,591 | 96.6 |

| Hispanic | 10,713 | 3.4 | 3,756 | 2.8 | 2,319 | 3.2 |

| Missing | 1,493 | 0.5 | 362 | 0.3 | 154 | 0.2 |

| Historic stage | ||||||

| Localized | 178,236 | 56.4 | 55,087 | 40.4 | 17,293 | 24.0 |

| Regional | 104,696 | 33.1 | 53,842 | 39.5 | 33,919 | 47.1 |

| Distant | 20,967 | 6.6 | 17,854 | 13.1 | 14,803 | 20.5 |

| Missing | 12,250 | 3.9 | 9,667 | 7.1 | 6,049 | 8.4 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| No cancer-directed surgery |

36,713 | 11.6 | 18,960 | 13.9 | 13,295 | 18.5 |

| BCS only | 27,066 | 8.6 | 10,625 | 7.8 | 4,033 | 5.6 |

| BCS + RT | 70,195 | 22.2 | 12,035 | 8.8 | 5,938 | 8.2 |

| Mastectomy | 182,175 | 57.6 | 94,830 | 69.5 | 48,798 | 67.7 |

| SEER location | ||||||

| San Francisco, CA | 52,878 | 16.7 | 22,588 | 16.6 | 11,449 | 15.9 |

| Connecticut | 52,638 | 16.7 | 24,240 | 17.8 | 12,565 | 17.4 |

| Detroit, MI | 53,856 | 17.0 | 25,937 | 19.0 | 14,298 | 19.8 |

| Hawaii | 12,492 | 4.0 | 3,880 | 2.8 | 2,146 | 3.0 |

| Iowa | 40,592 | 12.8 | 19,455 | 14.3 | 9,866 | 13.7 |

| New Mexico | 16,799 | 5.3 | 6,847 | 5.0 | 3,893 | 5.4 |

| Seattle, WA | 44,924 | 14.2 | 16,911 | 12.4 | 8,707 | 12.1 |

| Utah | 15,923 | 5.0 | 6,525 | 4.8 | 3,415 | 4.7 |

| Atlanta, GA | 26,047 | 8.2 | 10,067 | 7.4 | 5,725 | 7.9 |

| Total | 316,149 | 100.0 | 136,450 | 100.0 | 72,064 | 100.0 |

BCS indicates breast conserving surgery; RT, radiation therapy.

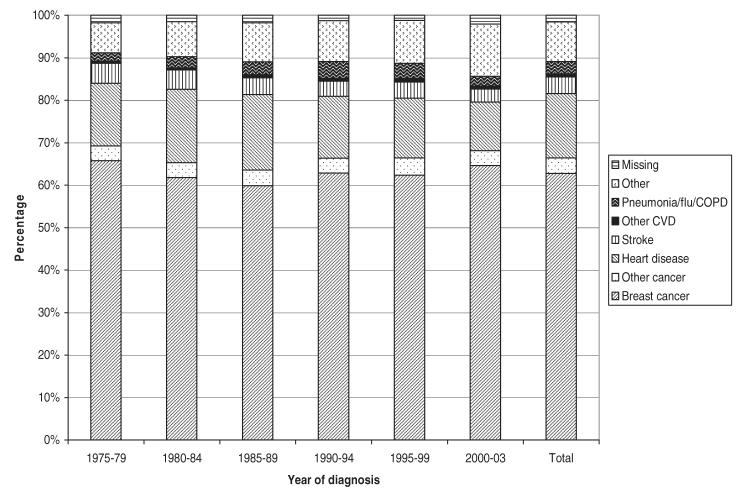

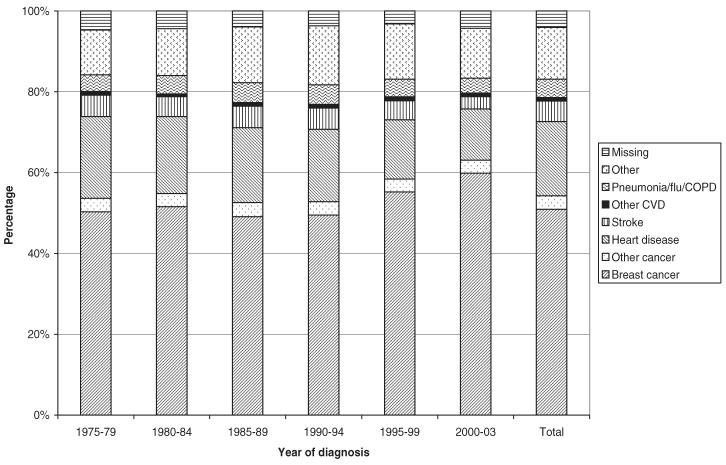

Table 2 presents the causes of death stratified by the years of follow-up and by the length of survival time (<1, 1–3, 4–5, 6–10, 11–15, >15 years). Overall, among patients who died, 52.8% of deaths were due to breast cancer, 17.8% were due to heart disease, 4.9% were due to stroke, 3.4% were due to other cancers besides breast, 20.2% were due to other causes, and 3.7% of deaths were unknown. Among those cases that died within 1 year of diagnosis, the proportion of death due to breast cancer was relatively stable over time (60%–66%). The proportions of death due to heart disease and stroke decreased slightly whereas death due to other causes increased. In women who survived longer, the percentage of death due to breast cancer decreased over time. For example, in those who died between 13 and 36 months after diagnosis, the percentage of death due to breast cancer decreased from 71.2% in the cohort of patients diagnosed in 1975–1979 to 62.7% in patients diagnosed in 1995–1999. In those who died between 61 and 120 months after diagnosis, the percentage of death due to breast cancer decreased from 53% in patients diagnosed in 1975–1979 to 39% in patients diagnosed in 1990–1994. In those who died 10 or more years after diagnosis, the majority of deaths were due to causes other than breast cancer, mostly cardiovascular diseases (heart disease or stroke). During all time periods, the percentage of patients with missing information on the cause of death was relatively stable. The proportion of death due to various causes was presented in Figure 1 for those who died within 1 year and in Figure 2 for those died after 1 or more years after diagnosis. From these figures, it was found that the proportion of death due to breast cancer was stable in those who died less than 1 year and slightly increased over time in those who died after 1 year of diagnosis.

TABLE 2.

Causes of Death and Change Over Time, Stratified by Survival and Follow-up Time

| Causes of Death |

Percentage of Causes of Death, by Year of Diagnosis and Length of Follow-up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1979 | 1980–1984 | 1985–1989 | 1990–1994 | 1995–1999 | 2000–2002 | |

| Died ≤12 mo in those with follow-up of ≥12 mo (N = 21,363) | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 65.8 | 61.7 | 59.9 | 62.9 | 62.4 | 64.0 |

| Other cancer | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| Heart disease | 14.7 | 17.3 | 17.8 | 14.6 | 14.1 | 11.8 |

| Stroke | 4.7 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.1 |

| Other CVD | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Respiratory | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.3 |

| Other | 7.1 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 12.6 |

| Missing | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Total N | 3,702 | 3,685 | 3,876 | 3,669 | 4,045 | 2,386 |

| Died during 13–36 mo in those with follow-up of ≥36 mo (N = 32,178) | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 71.2 | 70.8 | 67.8 | 65.2 | 62.7 | 59.4 |

| Other cancer | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Heart Disease | 11.9 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 13.9 |

| Stroke | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.1 |

| Other CVD | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Respiratory | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Other | 5.7 | 6.0 | 7.9 | 9.4 | 10.9 | 12.6 |

| Missing | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.8 |

| Total N | 5,886 | 6,355 | 6,556 | 6,343 | 5,963 | 2,386 |

| Died during 37–60 mo in those with follow-up of ≥60 mo (N = 22,539) | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 65.8 | 64.2 | 60.5 | 55.8 | 54.8 | - |

| Other cancer | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.5 | - |

| Heart disease | 15.3 | 15.6 | 15.1 | 16.9 | 14.5 | - |

| Stroke | 3.8 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.6 | - |

| Other CVD | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | - |

| Respiratory | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.5 | - |

| Other | 6.5 | 7.3 | 10.2 | 12.4 | 14.3 | - |

| Missing | 2.9 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.9 | - |

| Total N | 4,258 | 4,735 | 4,962 | 4,860 | 3,724 | - |

| Died during 61–120 mo in those with follow-up of ≥120 mo (N = 28,385) | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 53.0 | 52.2 | 45.4 | 39.0 | - | - |

| Other cancer | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4.2 | - | - |

| Heart disease | 20.7 | 19.0 | 20.5 | 21.6 | - | - |

| Stroke | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 6.4 | - | - |

| Other CVD | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | - | - |

| Respiratory | 3.4 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 6.1 | - | - |

| Other | 10.1 | 11.5 | 14.8 | 17.5 | - | - |

| Missing | 4.3 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 4.1 | - | - |

| Total N | 6,380 | 7,201 | 8,205 | 6,599 | - | - |

| Died during 121–180 mo in those with follow-up of ≥180 mo (N = 12,218) | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 37.0 | 34.6 | 28.5 | - | - | - |

| Other cancer | 3.9 | 4.1 | 5.5 | - | - | - |

| Heart disease | 24.9 | 25.8 | 24.3 | - | - | - |

| Stroke | 7.2 | 6.6 | 8.0 | - | - | - |

| Other CVD | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 | - | - | - |

| Respiratory | 6.2 | 7.3 | 7.3 | - | - | - |

| Other | 14.2 | 15.3 | 19.6 | - | - | - |

| Missing | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | - | - | - |

| Total N | 3,662 | 4,202 | 4,354 | - | - | - |

| Died ≥181 mo in those with follow-up of ≥180 mo (N = 9,979) | ||||||

| Breast cancer | 18.8 | 20.0 | 21.4 | - | - | - |

| Other cancer | 5.2 | 5.6 | 5.5 | - | - | - |

| Heart disease | 30.3 | 26.6 | 24.0 | - | - | - |

| Stroke | 7.8 | 8.0 | 7.1 | - | - | - |

| Other CVD | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | - | - | - |

| Respiratory | 8.1 | 7.5 | 8.0 | - | - | - |

| Other | 20.4 | 22.8 | 24.1 | - | - | - |

| Missing | 7.8 | 7.6 | 8.3 | - | - | - |

| Total N | 4,995 | 3,650 | 1,134 | - | - | - |

CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of deaths due to various causes by year of diagnosis for breast cancer patients who died within 12 months of diagnosis, 1975–2003.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of deaths due to various causes by year of diagnosis for breast cancer patients who died more than 1 year after diagnosis, 1975–2003.

Table 3 presents the odds ratios of dying of breast cancer from simple and multiple logistic regression models by the 6 different time periods. Model 1 was the unadjusted odds ratio without controlling for other factors. Model 2 adjusted for age, race, and Hispanic ethnicity. Model 3 adjusted for tumor stage in addition to the previous factors. Among patients with breast cancer who died within 12months after diagnosis, those diagnosed in 1980–1989 were slightly less likely to die of breast cancer as underlying cause of death compared with those diagnosed in 1975–1979, whereas those diagnosed in 1990–2002 did not vary significantly after adjusting for age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, and tumor stage. Among cases who died between 13 and 120 months after diagnosis, those diagnosed in later years were significantly less likely to die of breast cancer as the underlying cause of death than those in the late 1970s (1975–1979). For example, the adjusted risk of death due to breast cancer between 37–60 months in women diagnosed in 1995–1998 was significantly lower than those in 1975–1979 (odds ratio = 0.79, 95% confidence interval = 0.70–0.89). The trend of odds ratio over time was significant (P < 0.01). However, those long-term survivors who were diagnosed in 1980–1988 and died 15 years later were more likely to die of breast cancer as the underlying cause of death than those in 1975–1979.

TABLE 3.

Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios for the Likelihood of Death due to Breast Cancer in Different Time Periods

| Year of Diagnosis |

Model 1* |

Model 2† |

Model 3‡ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Survived ≤12 mo and followed-up for ≥12 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.81 | 0.73–0.90 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.96 | 0.88 | 0.78–0.99 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.75 | 0.68–0.83 | 0.79 | 0.71–0.88 | 0.79 | 0.70–0.89 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.82 | 0.74–0.92 | 0.89 | 0.80–0.99 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.04 |

| 1995–1999 | 0.83 | 0.75–0.93 | 0.90 | 0.81–1.00 | 0.93 | 0.82–1.05 |

| 2000–2002 | 0.81 | 0.72–0.92 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.04 | 0.96 | 0.83–1.10 |

| Survived 13–36 mo and followed-up for ≥36 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.99 | 0.92–1.08 | 1.05 | 0.96–1.15 | 1.04 | 0.95–1.15 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.87 | 0.81–0.94 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.96 | 0.88–1.06 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.77 | 0.71–0.83 | 0.87 | 0.80–0.95 | 0.94 | 0.86–1.04 |

| 1995–1999 | 0.68 | 0.63–0.74 | 0.80 | 0.73–0.87 | 0.89 | 0.81–0.97 |

| 2000 | 0.59 | 0.51–0.67 | 0.74 | 0.63–0.86 | 0.80 | 0.68–0.95 |

| Survived 37–60 mo and followed-up for ≥60 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.01 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.08 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.08 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.80 | 0.73–0.87 | 0.91 | 0.83–1.01 | 0.96 | 0.86–1.06 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.65 | 0.60–0.71 | 0.77 | 0.70–0.85 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.95 |

| 1995–1998 | 0.62 | 0.56–0.68 | 0.73 | 0.66–0.81 | 0.79 | 0.71–0.89 |

| Survived 61–120 mo and followed-up for ≥120 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.04 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | 1.03 | 0.95–1.12 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.74 | 0.69–0.79 | 0.88 | 0.81–0.95 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.00 |

| 1990–1993 | 0.56 | 0.52–0.60 | 0.67 | 0.61–0.72 | 0.73 | 0.67–0.79 |

| Survived 121–180 mo and followed-up for ≥180 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.02 | 1.01 | 0.90–1.12 | 1.00 | 0.90–1.12 |

| 1985–1988 | 0.69 | 0.63–0.76 | 0.80 | 0.72–0.89 | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 |

| Survived ≥181 mo and followed-up for ≥180 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 1.12 | 1.00–1.25 | 1.30 | 1.19–1.50 | 1.32 | 1.17–1.49 |

| 1985–1988 | 1.21 | 1.04–1.41 | 1.60 | 1.40–1.95 | 1.66 | 1.40–1.96 |

Model 1 did not adjust for other factors.

Model 2 adjusted for age (continuous), race, and Hispanic ethnicity.

Model 3 adjusted for age (continuous), race, Hispanic ethnicity and tumor stage.

To assess the potential bias because of missing information on the cause of death, further analyses excluded those cases (Table 4). After excluding those with missing data on the cause of death, the magnitude and trend of odds ratios were similar to that presented in Table 3.

TABLE 4.

Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios for the Likelihood of Death due to Breast Cancer in Different Time Periods, by Excluding Cases With Missing Information on Cause of Death

| Year of Diagnosis |

Model 1 |

Model 2† |

Model 3‡ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Died ≤12 mo in those with follow-up of ≥12 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.80 | 0.72–0.89 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.96 | 0.87 | 0.77–0.98 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.74 | 0.67–0.82 | 0.78 | 0.70–0.87 | 0.77 | 0.68–0.87 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.81 | 0.72–0.90 | 0.87 | 0.78–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.79–1.01 |

| 1995–1999 | 0.82 | 0.74–0.91 | 0.88 | 0.79–0.99 | 0.90 | 0.80–1.02 |

| 2000–1902 | 0.81 | 0.72–0.92 | 0.93 | 0.81–1.05 | 0.96 | 0.84–1.11 |

| Died during 13–36 mo in those with follow-up of ≥36 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.97 | 0.89–1.05 | 1.03 | 0.94–1.13 | 1.02 | 0.92–1.12 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.83 | 0.77–0.90 | 0.89 | 0.81–0.97 | 0.92 | 0.83–1.01 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.72 | 0.66–0.78 | 0.82 | 0.75–0.90 | 0.89 | 0.80–0.98 |

| 1995–1999 | 0.63 | 0.58–0.69 | 0.75 | 0.68–0.82 | 0.83 | 0.75–0.92 |

| 2000 | 0.57 | 0.49–0.66 | 0.73 | 0.62–0.87 | 0.81 | 0.68–0.97 |

| Died during 37–60 mo in those with follow-up of ≥60 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.95 | 0.87–1.04 | 1.01 | 0.91–1.12 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.13 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.79 | 0.72–0.86 | 0.90 | 0.81–1.00 | 0.95 | 0.85–1.06 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.64 | 0.58–0.70 | 0.77 | 0.69–0.85 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.96 |

| 1995–1998 | 0.61 | 0.55–0.67 | 0.72 | 0.65–0.81 | 0.79 | 0.70–0.89 |

| Died during 61–120 mo in those with follow-up of ≥120 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.97 | 0.90–1.04 | 1.04 | 0.95–1.12 | 1.03 | 0.95–1.12 |

| 1985–1989 | 0.72 | 0.68–0.78 | 0.86 | 0.80–0.93 | 0.91 | 0.84–0.99 |

| 1990–1993 | 0.55 | 0.51–0.59 | 0.66 | 0.60–0.72 | 0.72 | 0.66–0.78 |

| Died during 121–180 mo in those with follow-up of ≥180 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.02 | 1.01 | 0.91–1.13 | 1.01 | 0.90–1.12 |

| 1985–1988 | 0.68 | 0.62–0.75 | 0.80 | 0.72–0.90 | 0.84 | 0.75–0.94 |

| Died ≥181 mo in those with follow-up of ≥180 mo | ||||||

| 1975–1979 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1980–1984 | 1.12 | 1.00–1.25 | 1.36 | 1.21–1.54 | 1.35 | 1.19–1.52 |

| 1985–1988 | 1.22 | 1.05–1.43 | 1.74 | 1.47–2.06 | 1.74 | 1.47–2.06 |

Model 1 did not adjust for other factors.

Model 2 adjusted for age (continuous), race, and Hispanic ethnicity.

Model 3 adjusted for age (continuous), race, Hispanic ethnicity and tumor stage.

Table 5 presents the proportion and adjusted odd ratios of death due to breast cancer by factors other than the year of diagnosis, including age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, tumor stage, treatment, and geographic location. Model 1 adjusted for age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, tumor stage, treatment, and geographic area, whereas model 2 adjusted for the variables in model 1 and year of diagnosis. The percentage of death due to breast cancer decreased significantly with age. For example, 87.9% of deaths in women aged <40 were because of breast cancer compared with 30.7% in those aged 80 or older. Women aged 40 to 49 were 40% less likely and those aged >70 were over 90% less likely to die of breast cancer compared with those <40 years of age (model 1). When additionally controlling for the year of diagnosis, the risk of death due to breast cancer by age groups was almost unchanged (model 2). There was no significant racial/ethnic variation in the likelihood of death due to breast cancer. As expected, women diagnosed with advanced stage were more likely to die of the disease. For example, those with distant stage were over 8 times more likely to die of breast cancer than those with local stage disease (odds ratio = 8.84, 95% confidence interval = 8.41–9.28). The odds ratio of death due to breast cancer was significantly lower in women receiving cancer-directed surgeries than those who did not. In those with no cancer-directed surgery, 31.4% were of local stage, 21.0% were of regional stage, 26.5% were of distant stage, and 21.1% were of unknown stage. There were also some geographic variations across the 9 SEER areas.

TABLE 5.

Breast Cancer as the Underlying Cause of Death Among All Deaths, by Patient and Tumor Characteristics, 1975–2003

| Characteristics | Deaths (N) | Deaths Due to Breast Cancer (%) |

Odds Ratio* of Death Due to Breast Cancer (Model 1) |

Odds Ratio† of Death Due to Breast Cancer (Model 2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Age | ||||||

| <40 | 7,464 | 87.9 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 40–49 | 14,488 | 81.9 | 0.60 | 0.55–0.65 | 0.60 | 0.55–0.65 |

| 50–59 | 21,969 | 72.4 | 0.34 | 0.31–0.36 | 0.34 | 0.31–0.37 |

| 60–69 | 30,067 | 54.5 | 0.15 | 0.14–0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14–0.17 |

| 70–79 | 33,869 | 37.1 | 0.08 | 0.07–0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07–0.08 |

| 80+ | 28,593 | 30.7 | 0.05 | 0.05–0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05–0.05 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 119,008 | 51.5 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black | 12,395 | 62.7 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.06 | 0.98 | 0.94–1.03 |

| Asian | 4,413 | 60.8 | 1.06 | 0.97–1.16 | 1.01 | 0.92–1.10 |

| American Indian | 417 | 66.2 | 1.10 | 0.87–1.40 | 1.05 | 0.82–1.34 |

| Missing | 217 | 37.8 | 0.45 | 0.29–0.69 | 0.48 | 0.31–0.74 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 132,332 | 52.6 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Hispanic | 3,756 | 61.7 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.13 | 1.00 | 0.92–1.09 |

| Missing | 362 | 42.5 | 0.82 | 0.59–1.15 | 0.76 | 0.54–1.06 |

| Historic stage | ||||||

| Localized | 55,087 | 31.4 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Regional | 53,842 | 63.0 | 3.13 | 3.04–3.22 | 3.11 | 3.03–3.20 |

| Distant | 17,854 | 82.9 | 9.00 | 8.57–9.46 | 8.84 | 8.41–9.28 |

| Missing | 9,667 | 62.6 | 3.94 | 3.72–4.18 | 3.93 | 3.71–4.16 |

| Treatment | ||||||

| No cancer-directed surgery | 18,960 | 70.1 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| BCS only | 10,625 | 38.0 | 0.57 | 0.54–0.61 | 0.54 | 0.50–0.57 |

| BCS + RT | 12,035 | 49.3 | 0.69 | 0.65–0.73 | 0.64 | 0.60–0.68 |

| MRM | 94,830 | 51.5 | 0.63 | 0.60–0.66 | 0.66 | 0.63–0.70 |

| SEER location | ||||||

| San Francisco-CA | 22,588 | 50.7 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| Connecticut | 24,240 | 51.8 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | 1.11 | 1.07–1.16 |

| Detroit-MI | 25,937 | 55.1 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | 1.11 | 1.06–1.15 |

| Hawaii | 3,880 | 55.3 | 1.00 | 0.91–1.10 | 0.99 | 0.90–1.09 |

| Iowa | 19,455 | 50.7 | 1.32 | 1.26–1.38 | 1.30 | 1.24–1.36 |

| New Mexico | 6,847 | 56.9 | 1.21 | 1.14–1.30 | 1.18 | 1.11–1.26 |

| Seattle-WA | 16,911 | 51.5 | 1.13 | 1.08–1.19 | 1.11 | 1.06–1.17 |

| Utah | 6,525 | 52.3 | 1.19 | 1.11–1.27 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.22 |

| Atlanta-GA | 10,067 | 56.9 | 1.09 | 1.03–1.15 | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 |

| Total | 136,450 | 52.8 | - | - | - | - |

Adjusted for age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, tumor stage, treatment, and geographic area.

Adjusted for the above variables plus year of diagnosis.

Adjusting for hormone receptor status (estrogen or progesterone receptor positivity), tumor size and grade in addition to other confounders for cases in later time periods (after 1988 when these data became available) did not alter the results (Table 6). This table also shows that the proportion of death due to breast cancer was higher in women with negative hormone receptor, larger tumor size, and poorer tumor grade, after controlling for the year of diagnosis, demographics, tumor stage, treatment, and geographic area.

TABLE 6.

Breast Cancer as the Underlying Cause of Death Among All Deaths, by Patient and Tumor Characteristics, 1988–2003

| Characteristics | Deaths (N) | Deaths Due to Breast Cancer (%) |

Odds Ratio* of Death Due to Breast Cancer |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | |||

| Age | ||||

| <40 | 3,184 | 89.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| 40–49 | 6,406 | 85.1 | 0.64 | 0.56–0.74 |

| 50–59 | 7,778 | 77.6 | 0.40 | 0.35–0.46 |

| 60–69 | 10,742 | 58.6 | 0.19 | 0.17–0.21 |

| 70–79 | 15,071 | 39.2 | 0.09 | 0.08–0.11 |

| 80+ | 15,608 | 32.0 | 0.06 | 0.05–0.07 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 49,631 | 51.6 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black | 6,444 | 65.5 | 0.91 | 0.85–0.98 |

| Asian | 2,367 | 62.7 | 1.04 | 0.75–1.45 |

| American Indian | 254 | 68.9 | 0.94 | 0.82–1.06 |

| Missing | 93 | 39.8 | 0.48 | 0.27–0.87 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | 56,473 | 53.3 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Hispanic | 2,071 | 63.3 | 0.92 | 0.82–1.04 |

| Missing | 245 | 44.9 | 0.69 | 0.48–0.98 |

| Historic stage | ||||

| Localized | 23,930 | 29.4 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Regional | 20,547 | 65.3 | 2.69 | 2.57–2.82 |

| Distant | 9,511 | 84.1 | 6.70 | 6.21–7.24 |

| Missing | 4,801 | 64.1 | 3.73 | 3.38–4.12 |

| Treatment | ||||

| No cancer-directed surgery | 10,218 | 71.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| BCS only | 7,882 | 38.1 | 0.66 | 0.60–0.72 |

| BCS + RT | 8,715 | 48.4 | 0.80 | 0.73–0.88 |

| MRM | 31,974 | 53.1 | 0.69 | 0.64–0.75 |

| SEER location | ||||

| San Francisco-CA | 9,018 | 52.3 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Connecticut | 9,909 | 51.4 | 1.08 | 1.00–1.16 |

| Detroit-MI | 11,047 | 55.1 | 1.07 | 1.00–1.15 |

| Hawaii | 1,863 | 56.4 | 0.98 | 0.85–1.13 |

| Iowa | 8,045 | 50.4 | 1.19 | 1.10–1.28 |

| New Mexico | 3,294 | 57.9 | 1.21 | 1.09–1.34 |

| Seattle-WA | 7,607 | 53.2 | 1.13 | 1.05–1.22 |

| Utah | 3,092 | 53.1 | 1.18 | 1.07–1.31 |

| Atlanta-GA | 4,914 | 59.8 | 1.06 | 0.97–1.16 |

| Hormone receptor status† | ||||

| Positive | 24,921 | 47.3 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Negative | 9,278 | 73.4 | 1.77 | 1.66–1.89 |

| Unknown | 24,590 | 52.6 | 1.02 | 0.97–1.08 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well differentiated | 3,434 | 19.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Moderately differentiated | 13,191 | 43.3 | 1.83 | 1.65–2.04 |

| Poorly differentiated | 20,348 | 67.6 | 2.82 | 2.54–3.13 |

| Unknown | 21,816 | 52.2 | 1.83 | 1.65–2.04 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| <1.0 | 4,432 | 23.4 | 1.00 | Referent |

| 1.0–1.99 | 13,124 | 34.9 | 1.46 | 1.33–1.60 |

| 2.0–2.99 | 11,644 | 50.6 | 2.09 | 1.91–2.29 |

| 3.0–3.99 | 6,574 | 59.9 | 2.50 | 2.26–2.77 |

| 4.0+ | 12,952 | 72.6 | 2.91 | 2.64–3.20 |

| Unknown | 10,063 | 66.3 | 2.46 | 2.21–2.73 |

| Total | 58,789 | 53.6 | - | - |

Adjusted for age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, tumor stage, treatment, geographic area, year of diagnosis, hormone receptor status, tumor grade, and tumor size.

Positive hormone receptor status represents either estrogen or progesterone receptor positive.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the competing causes of death and changes over time among women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Overall, among all patients who were diagnosed with breast cancer and died between 1975 and 2003, the underlying cause of death was 52.8% due to breast cancer, 17.8% due to heart disease, 4.9% due to stroke, 3.4% due to other cancers, and 20.2% due to other causes. The percentage of death due to breast cancer did not change significantly over time from 1975 to 2003 in those who died within 12 months of diagnosis, but decreased significantly in women who died between 1 and 15 years after diagnosis. The percentage of death due to breast cancer significantly decreased with age and increased with advanced tumor stage, but did not vary significantly by race or ethnicity.

Thanks to advances in technology and medical care for early detection and treatment, many women diagnosed with breast cancer can survive longer than ever before.5–17 Studies have shown that breast cancer mortality decreased and relative survival increased over the past decades,1–3 which may be inflated because of overdiagnosis.27,28 However, the trend in competing causes of death in women with breast cancer over the past 30 years has not been well documented. Schairer et al22 reported the probabilities of death from breast cancer and other causes among female patients with breast cancer and concluded that these probabilities varied substantially by tumor stage and age at diagnosis. Diab et al20 studied the tumor characteristics of elderly women with breast cancer and found that relative contribution of breast cancer death to the overall causes of mortality decreased by age from 73% in women aged 50 to 54 to 29% in women aged 85 or older. However, whether the competing causes of death for patients with breast cancer changed over time was not addressed in these studies. We found that about half of women with breast cancer died of causes other than breast cancer, and the proportion of death due to breast cancer decreased significantly over time after 1 year of diagnosis. This finding is important because breast cancer now may not be perceived as life-threatening as it used to be because patients with this disease can survive for more years than ever before.

Among patients with breast cancer who died of other causes, heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death. Because the risk of heart disease and stroke increases dramatically with age, the proportion of cases who died of heart disease and stroke increases significantly with age.29 This pattern is similar to the cause of death for general population aged ≥65 in the United States and around the world.30–36 Particularly, in the population aged 80 or older, the significant majority will die of heart disease, stroke, or other causes such as fall and dementia.29 Other diseases such as diabetes and obesity are increasingly becoming a concern. Therefore, prevention and treatment of these diseases are critically important for both patients with cancer and for general population. The main risk factors of these leading causes of deaths are tobacco (18.1% of total US deaths), poor diet and physical inactivity (16.6%), and alcohol consumption (3.5%).30,34 These leading causes of death were also the main contributors to disparities in mortality in relation to socioeconomic status and race or ethnicity, whereas cancer accounted for 3.3% of racial disparities in mortality.33 Implications of these studies are that prevention and treatment of heart disease, stroke, and associated risk factors will benefit people with or without cancer.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, the cause of death for patients with breast cancer was obtained from the National Death Index, which was primarily based on death certificates from local hospitals. These death certificates may not accurately reflect the true cause of deaths.37–39 Therefore, nondifferential misclassification of the cause of death is likely. Second, over the past 30 years, the definitions of diseases and technology in ascertaining the cause of disease have changed substantially. These changes might have affected the classification of the causes of death. Third, although the 9 SEER registries accounted for 14% of the US population, the results from these studies may not be generalizable to the entire nation. In addition, over the past decade, mammography screening has been effective in detecting in situ tumors and shifting invasive tumor toward earlier stages and smaller tumor sizes. Because our study population included women who had breast cancer as the first invasive tumor, those with in situ cases were excluded from the study. However, tumor stages were adjusted for in this study. Also, when tumor size, grade, and hormone receptor status were controlled for in the analysis, the results remained similar. Furthermore, we only include women who were diagnosed with breast cancer as the only primary tumor. Those patients with presence of other primary malignancies may have had more complicated competing courses of death. Finally, information on adjuvant chemotherapy and hormonal therapy is not available in SEER data. Although these adjuvant therapies have been effective in reducing all-cause and disease-specific mortality in women with breast cancer, no studies have shown that this will alter the patterns of competing causes of death over time. However, some chemotherapy regimens, particularly anthracycline-containing agents, are known to have cardiac toxicity.40–42 The risk of heart disease is relatively small and the impact of this toxicity on the overall patterns of competing causes of deaths over time may be minimal, if any.

In conclusion, overall, the underlying cause of death was 52.8% due to breast cancer, 17.8% due to heart disease, and 4.9% due to stroke. The percentage of death due to breast cancer as the underlying cause of death significantly decreased over time from 1975 to 2003 in women with breast cancer after 1 year of diagnosis, decreased significantly with age, and increased with advanced tumor stage, but did not vary by race or ethnicity. The findings demonstrated that the impact of breast cancer on the risk of overall death was reduced after 1 year of diagnosis, but suggested the need for continued cancer surveillance.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute Grant R01-CA090626.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ries LAG, Harkins D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003 2006National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2003/, based on November 2005 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER Web site Accessed February 14, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute Cancer of the breast Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html Accessed November 10, 2006

- 3.American Cancer Society Cancer facts and figures 2006 Available at: www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2006PWSecured.pdf Accessed November 10, 2006

- 4.Howe HL, Wu X, Ries LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2003, featuring cancer among US Hispanic/ Latino populations. Cancer. 2006;107:1711–1742. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Kessler LG, et al. Recent trends in US breast cancer incidence, survival, and mortality rates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1571–1579. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabar L, Yen MF, Vitak B, et al. Mammography service screening and mortality in breast cancer patients: 20-year follow-up before and after introduction of screening. Lancet. 2003;361:1405–1410. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tornberg S, Kemetli L, Lynge E, et al. Breast cancer incidence and mortality in the Nordic capitals, 1970–1998. Trends related to mammography screening programmes. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:528–535. doi: 10.1080/02841860500501610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swedish Organised Service Screening Evaluation Group Reduction in breast cancer mortality from organized service screening with mammography. I. Further confirmation with extended data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:45–51. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1227–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1233–1241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer. An overview of the randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1444–1455. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gebski V, Lagleva M, Keech A, et al. Survival effects of postmastectomy adjuvant radiation therapy using biologically equivalent doses: a clinical perspective. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:26–38. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;352:930–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;351:1451–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Favourable and unfavourable effects on long-term survival of radiotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1757–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;366:2087–2106. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welch HG, Albertsen PC, Nease RF, et al. Estimating treatment benefits for the elderly: the effect of competing risks. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:577–584. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-6-199603150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fish EB, Chapman JW, Link MA. Competing causes of death for primary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:368–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02303502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diab SG, Elledge RM, Clark GM. Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:550–556. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basche M, Byers T. Re: tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer [letter] J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:64–65. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schairer C, Mink PJ, Carroll L, et al. Probabilities of death from breast cancer and other causes among female breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1311–1321. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute SEER 1973-2003 public-use data Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/publicdata/ Accessed November 16, 2006

- 24.National Institutes of Health consensus development conference statement: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, November 1–3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:979–989. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.13.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokes M, Davis C, Koch G. Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stata Corp . STATA Statistical Software, Release 7.0. Stata Corp; College Station, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zackrisson S, Andersson I, Janzon L, et al. Rate of over-diagnosis of breast cancer 15 years after end of Malmö mammographic screening trial: follow-up study. BMJ. 2006;332:689–692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38764.572569.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moller H, Davies E. Over-diagnosis in breast cancer screening. BMJ. 2006;332:691–692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38768.401030.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2006 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans 2006. DHHS Publication No. 2006–1232. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Single E, Rehm J, Robson L, et al. The relative risks and etiologic fractions of different causes of death and disease attributable to alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use in Canada. CMAJ. 2000;162:1669–1675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, et al. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1585–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2005 With Chartbook on Trends in the Health of Americans 2005183 DHHS Publication No. 2005–1232. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Percy C, Stanek E, III, Gloeckler L. Accuracy of cancer death certificates and its effect on cancer mortality statistics. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:242–250. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sehdev Smith AE, Hutchins GM. Problems with proper completion and accuracy of the cause-of-death statement. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:277–284. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roulson J, Benbow EW, Hasleton PS. Discrepancies between clinical and autopsy diagnosis and the value of post mortem histology: a meta-analysis and review. Histopathology. 2005;47:551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shapiro CL, Recht A. Drug therapy: side effects of adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1997–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Partridge AH, Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Side effects of chemotherapy and combined chemohormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;30:135–142. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loerzel VW, Dow KH. Cardiac toxicity related to cancer treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7:557–562. doi: 10.1188/03.CJON.557-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]