Abstract

Podosomes and immunes synapses are integrin-mediated adhesive structures that share a common ring-like morphology. Both podosomes and immune synapses have a central core surrounded by a peripheral ring containing talin, vinculin and paxillin. Recent progress suggests significant parallels between the regulatory mechanisms that contribute to the formation of these adhesive structures. In this review, we compare the structures, functions and regulation of podosomes and the immune synapse.

Keywords: Podosome, Invadopodia, Immune synapse

Introduction

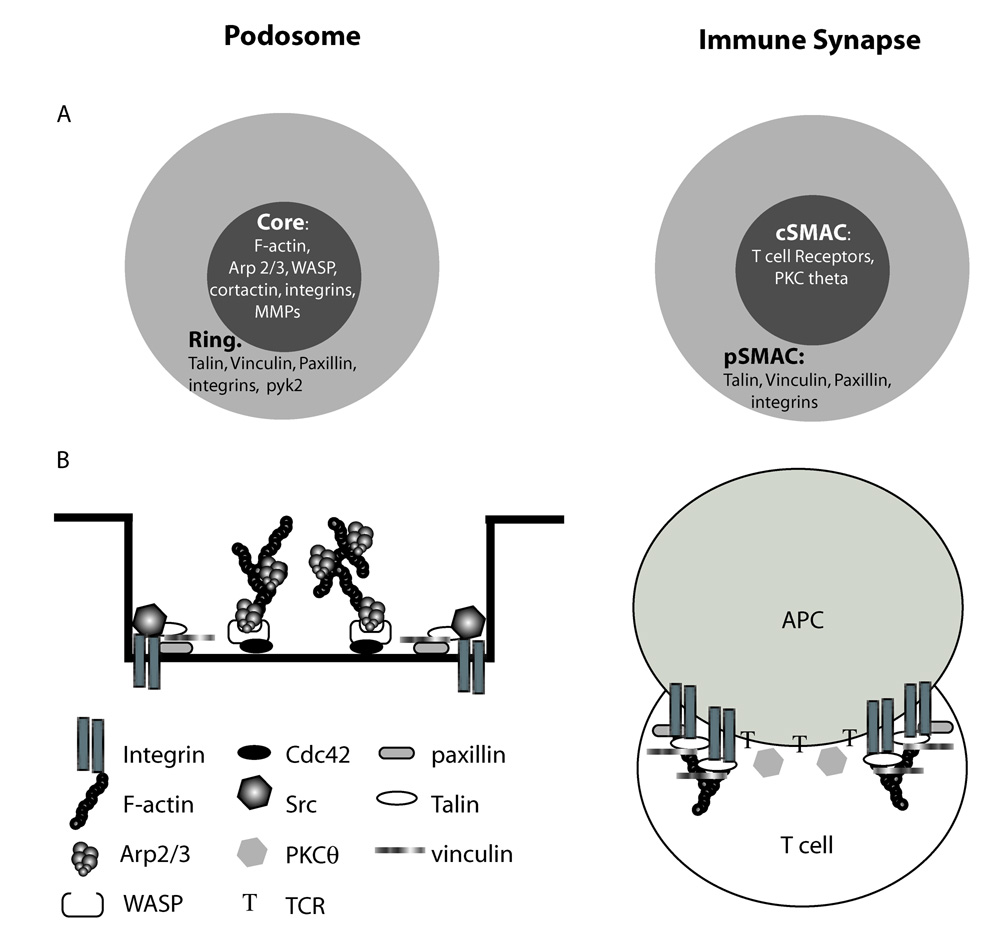

Cell migration requires that cells interact with their environment through dynamic contacts with the extracellular matrix (ECM) or with other cells. For highly migratory and invasive cells including dendritic cells, macrophages, osteoclasts, and transformed fibroblasts, these interactions frequently take the form of dynamic adhesions, known as podosomes that are located on the ventral surface of cells (Linder, 2007). Podosomes are integrin-mediated adhesions that contain a central actin core surrounded by a ring of cytoskeletal proteins such as talin and vinculin (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003). Podosome architecture is reminiscent of the macromolecular structure found between a T cell and an antigen-presenting cell (APC), termed the immune synapse. The immune synapse is most broadly defined as the interface between a T cell and an APC (Norcross, 1984). Microscopic examinations have shown that, like podosomes, the immune synapse adopts a concentric ring form, where the central signaling region is surrounded by the αLβ2 integrin, leukocyte function antigen-1 (LFA-1), along with cytoskeletal adaptors talin and vinculin (Monks et al., 1998; Nolz et al., 2007) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Podosomes and the immune synapse share a common morphology. Schematic representation of the podosome and immune synapse shared ring-like structure. (A) Top view of podosomes and immune synapse. (B) Frontal view of podosome (adapted from (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003)) and immune synapse. For details, see text.

While both podosomes and the immune synapse can take many shapes and seem to serve distinct functions, they share a number of regulatory molecules and are both responsible for directing specific cell responses. In this review, we compare the structures of podosomes and the immune synapse, factors involved in ECM degradation in podosomes and directed cell killing by T cells, and regulators of assembly and disassembly of these structures.

Structure and function of podosomes

Podosomes are comprised of a central actin core surrounded by a ring of cytoskeletal adaptor proteins such as talin, paxillin and vinculin (Marchisio et al., 1988; Mueller et al., 1992). These characteristic podosome ring units may be found as isolated puncta on the ventral surface of cells or they may aggregate to form larger rosettes (Gavazzi et al., 1989; Linder, 2007). In addition to being found in monocyte-derived cells and transformed fibroblasts, podosomes have also been reported in lymphocytes (Carman et al., 2007), endothelial cells (Tatin et al., 2006), and smooth muscle cells (Hai et al., 2002). In carcinoma cells, podosome-like structures termed “invadopodia” are formed in areas associated with membrane protrusion and matrix degradation (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003). Although, invadopodia are generally considered to be longer-lived than podosomes, these structures share many regulatory components and the capacity for matrix degradation. For the purposes of this review, “podosomes and invadopodia” will be referred to as “podosomes-type adhesions” (PTAs) (Linder, 2007)

One feature that distinguishes PTAs from focal adhesions, another type of integrin-mediated adhesive structure found in fibroblasts, is the absence of actin stress fibers and the presence of actin dot-like structures. The podosome core is a site of active actin polymerization, and F-actin may be found along with the actin nucleator Arp2/3 and regulatory proteins Wiskott Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), cortactin and gelsolin (Buccione et al., 2004). Integrins, including β1, β2, and β3 integrins, may be found in either the core or ring structure (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003). The protein kinases, Src (Gavazzi et al., 1989), protein kinase C (PKC) (Teti et al., 1992), protein tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) (Bruzzaniti et al., 2005), and members of the Rho family of Rho GTPases (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003; Chellaiah, 2006) are also found at podosomes.

The physiological relevance of PTA formation in vivo remains largely unknown, although the matrix-degrading capacity of PTAs has been implicated in crossing tissue boundaries during the trafficking of immune cells (Carman et al., 2007) and invasion of cancer cells (Linder, 2007). Accordingly, podosomes appear to be critical for normal functioning of the immune system, since mutations in the podosome component WASP are associated with the human immunodeficiency, Wiskott Aldrich syndrome (Linder et al., 1999). Furthermore, experimental evidence implicates an essential role for podosomes in the bone-resorptive functions of osteoclasts (Miyauchi et al., 1990).

Structure and function of immune synapses

Initial confocal microscopy of antigen-induced T cell/B cell conjugates revealed a bulls-eye pattern at the conjugate contact area (Monks et al., 1998). T cell receptors (TCRs) and associated signal transduction molecules like CD3 and PKCθ are found in the middle of the contact face, a region termed the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC) while LFA-1 and talin are enriched in a ring around the central zone, a region termed the peripheral supramolecular activation cluster (pSMAC) (Monks et al., 1998; Grakoui et al., 1999). The cSMAC has been proposed to be a site of TCR internalization, since TCRs are initially found in microclusters at the pSMAC that migrate into the central region (Varma et al., 2006). As in PTAs, the immune synapse is a site of active actin polymerization, and disruption of actin polymerization has significant effects on T cell activation. F-actin, the actin nucleator Arp 2/3, and regulatory proteins WASP, WAVE, and HS1 (the hematopoietic-specific homologue of cortactin) are all found at the face of the immune synapse along with the Rho GTPases, Cdc42 and Rac1 (Billadeau et al., 2007).

While investigations into podosomes have carefully localized molecules to central versus peripheral regions (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003), the structural organization of the immune synapse has not been as carefully defined, in part because the functional significance of the classical bulls-eye structure in vivo remains unknown. Recently, this ring-like structure was observed in cytotoxic T cell-mediated astrocyte killing in vivo, but it has yet to be observed in T cell-APC interactions (Barcia et al., 2006). To date, only the polarization of molecules toward the T cell-APC interface has been observed in vivo (Kawakami et al., 2005). Thus, investigators have typically characterized the composition of the immune synapse by the polarization of molecules toward the T cell-APC interface, and there has been substantial progress in defining the functional significance of these components to immune function using transgenic mouse models. In T cells, immune synapse formation influences immune response generation including proliferation of T cells, cytokine production, and cytolysis of target cells (Billadeau et al., 2007). As a result, characterization of molecules involved in immune synapse formation have focused less on structural composition and dynamics of the synapse and more on whether or not there are measurable differences in immune response generation with perturbation of specific components of the immune synapse in vivo.

ECM degradation and target cell lysis

PTAs and the immune synapse share a similar ability to polarize the secretion of degradative enzymes to the ECM and target cells, respectively. Formation of stable PTAs is a critical prelude to ECM degradation by cells (Yamaguchi et al., 2005). Three members of the matrix metalloprotease (MMP) family have been identified at PTAs, i.e. MT1-MMP, MMP2 and MMP9 (Linder, 2007). Investigations into factors involved in regulating the activity of these proteases remain limited, but integrin stimulation seems to be required for their activation (Coopman et al., 1996; Nakahara et al., 1998; Deryugina et al., 2001).

T cells are the primary cells responsible for generation of adaptive immune responses. Upon contacting an APC bearing the cognate peptide-MHC complex, T cells arrest and form stable contacts lasting for 8–12 hours (Mempel et al., 2004). This interaction is termed an immune synapse and is likely longer lived than PTAs, which persist for durations of minutes to hours (Yamaguchi et al., 2005; Linder, 2007). Cytotoxic T cells (CTL) are a subset of T cells responsible for the directed killing of host cells. For instance, during a viral infection, CTL are responsible for killing infected cells and also for destruction of immune cells during the resolution of infection. This killing is preceded by the formation of an immune synapse, which allows for the directed secretion of perforin and granzymes responsible for target cell destruction. CTL form a prototypic ring structure containing LFA-1 and talin in the periphery of the ring (Somersalo et al., 2004).

Assembly of podosomes

Extracellular stimulus and intracellular signaling

Recent progress has been made in identifying the molecular regulators of PTA formation. While the extracellular environment and integrin engagement are important, growth factors and cytokines including EGF (Yamaguchi et al., 2005), VEGF (Hiratsuka et al., 2006) and CSF-1 (Kheir et al., 2005; Yamaguchi et al., 2006) may also stimulate PTA formation. Downstream of extracellular stimulation, Src family kinase activity is both necessary (Suzuki et al., 1998) and sufficient (Chen, 1989) for PTA assembly. Src activity is involved in early signaling events during podosome assembly and both the kinase activity and scaffolding functions of Src seem to be important (Luxenburg et al., 2006). Additional regulatory kinases that are important for podosome formation include PKC (Tatin et al., 2006) and the FAK-related kinase Pyk2, which appears to be involved in Src recruitment (Bruzzaniti et al., 2005).

Rho-family GTPases

The Rho family of GTPases regulate the actin cytoskeleton and have been identified as important regulators of PTA formation (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003; Chellaiah, 2006). For instance, the loss of Rho activity through use of inhibitors or dominant-negative constructs impairs podosome formation in Src-transformed fibroblasts (Berdeaux et al., 2004). There is some controversy surrounding the activity of other Rho GTPase family members in formation of PTAs. For example, signaling through Cdc42 to WASP and Arp2/3 has been found to be critical for invadopodia formation in breast cancer cells (Yamaguchi et al., 2005). In contrast, Cdc42 activation led to podosome disassembly in macrophages (Linder et al., 1999). Furthermore, Rac2 activity is essential for podosome formation in macrophages based on knockout experiments (Wheeler et al., 2006). It is likely that regulation of PTAs requires a balance of signaling through members of the Rho family GTPases (Linder, 2007).

Actin regulatory proteins

F-actin polymerization and depolymerization within the podosome core is very dynamic with FRAP analysis demonstrating that the half-life of an actin filament is approximately 20 seconds (Evans et al., 2003). This rapid actin turnover requires the presence of actin regulatory molecules including Arp2/3 (Kaverina et al., 2003), WASP (Linder et al., 1999) and cortactin (Kempiak et al., 2005).

WASP and the non-hematopoietic homologue, N-WASP, are both necessary for generation of PTAs (Linder et al., 1999; Mizutani et al., 2002; Yamaguchi et al., 2005). Supporting an essential role for WASP in podosome formation, dendritic cells and macrophages from patients with Wiskott Aldrich syndrome lack podosomes (Jones et al., 2002). In contrast, WAVE1 and WAVE2 are not necessary for invadopodia formation (Yamaguchi et al., 2005). Recent work has shown siRNA targeting of WASP-interacting protein (WIP) results in impaired macrophage podosome formation indicating that the interaction of WASP and WIP are important for podosome formation (Tsuboi, 2007). Cortactin is another actin-binding protein that has been identified as an important regulator of podosome formation. Knockdown of cortactin in osteoclasts (Tehrani et al., 2006) and transformed fibroblasts (Webb et al., 2007) impairs formation of podosomes. The F-actin regulatory proteins gelsolin and cofilin are also important for PTA formation and stability. For instance, gelsolin knockout mice lack podosomes in osteoclasts and have impaired bone-degrading function (Chellaiah et al., 2000). Additionally, depletion of cofilin in breast cancer cells results in impaired invadopodia formation and matrix degradation (Yamaguchi et al., 2005).

Assembly of immune synapses

Extracellular stimulus and intracellular signaling

Immune synapse formation follows TCR ligation (Lee et al., 2002). The initial steps in this process are well-characterized: TCR ligation and cross-linking leads to the aggregation and activation of the CD3 complex via phosphorylation by the Src-family tyrosine kinase, Lck. Phosphorylated CD3 recruits the kinase Zap70, which is activated and goes on to phosphorylate several targets including the adaptors LAT and Slp-76. These proteins recruit a number of signaling molecules, resulting in macromolecular signaling complexes that permit the sensitive and sustained activation of effectors (Samelson, 2002). Increased LFA-1 adhesiveness following TCR engagement is a result of both LFA-1 clustering and transition to a high-affinity state (Dustin and Springer, 1989; Beals et al., 2001). These changes allow LFA-1 to form strong bonds between a T cell and an APC, a primary characteristic of the immune synapse. A critical regulator of LFA-1 adhesiveness and immune synapse formation is the cytoskeletal protein talin. Recently, we have found that actin polarization toward the immune synapse precedes recruitment of talin, LFA-1 activation and stabilization of the synapse (Simonson et al., 2006). Polarization of the actin cytoskeleton toward the face of the APC is important for stabilization of the synapse, appropriate T cell signaling and immune response generation (Billadeau et al., 2007).

Rho-family GTPases

Consistent with their involvement in PTA formation, the Rho GTPases, Rac1 and Cdc42 are both localized to the immune synapse following TCR stimulation (Cannon and Burkhardt, 2004). While the guanine exchange factors (GEFs) regulating the activity of Rac and Cdc42 in PTA formation have not yet been identified, two families of Rho GEFs have been associated with immune synapse formation following TCR ligation in T cells, i.e. Vav1 and DOCK2 (Fukui et al., 2001; Turner and Billadeau, 2002).

Vav1 has been identified as a critical regulator of LFA-1-mediated immune synapse formation in T cells (Krawczyk et al., 2002) and thymocytes (Ardouin et al., 2003). Following TCR ligation, the Vav1 is recruited to the immune synapse by the LAT-Slp-76 adaptors and IL-2 inducible kinase (ITK) (Tybulewicz, 2005). Vav1 then activates the Rho-GTPases, Cdc42 and Rac1, which in turn recruit the actin nucleators WASP (Zeng et al., 2003) and WAVE 1/2 protein complex (Zipfel et al., 2006), respectively.

Given the important role for Vav1 in immune synapse formation, it is possible that Vav or other GEFs may also be involved in PTA formation, although the role of specific GEFs in the regulation of PTAs has not been defined. Vav1 has been identified as a regulator of macrophage chemotaxis through its effects on Rac (Vedham et al., 2005), while the activity of a related isoform, Vav3, has been shown to regulate bone resorption in osteoclasts (Faccio et al., 2005). DOCK2 is another Rac GEF that has been identified as an important regulator of immune synapse formation (Sanui et al., 2003) and T cell signaling (Nishihara et al., 2002; Tanaka et al., 2007). DOCK2-deficient T cells show defective actin activity during T cell migration (Fukui et al., 2001) and also fail to polarize LFA-1 and PKCθ to the immune synapse following TCR ligation (Sanui et al., 2003).

Actin regulatory proteins

Following immune synapse formation, actin polymerization is required for stable T cell-APC interactions and T cell activation (Valitutti et al., 1995; Grakoui et al., 1999); however, the dynamics of this turnover remain unexplored. While WASP is the critical Arp2/3 regulator during PTA formation, depletion of WASP does not significantly impair immune synapse formation or its durability in T cells (Cannon and Burkhardt, 2004). In contrast, the WASP-related protein WAVE2 appears to be a critical Arp 2/3 regulator involved in immune synapse formation. Depletion of WAVE2 results in decreased conjugate formation and also impairs localization of vinculin and talin at the immune synapse (Nolz et al., 2006, 2007).

Similar to its role in podosomes, the hematopoietic cortactin homologue, HS-1, is also an important regulator of immune synapse formation. siRNA depletion of HS-1 results in decreased actin polarization toward the immune synapse and decreased synapse formation (Gomez et al., 2006). Additionally, this depletion results in signaling defects, such as impaired calcium flux and IL-2 production.

The role of actin-binding proteins with actin-severing activity such as cofilin has been better studied in PTAs than in immune synapse regulation. Using immunofluorescence, cofilin has been identified as a peripheral immune synapse component (Eibert et al., 2004). Following introduction of peptides designed to interfere with cofilin-actin interactions in human T cells, there was a decrease in conjugate formation and a decrease in proliferation and cytokine production (Eibert et al., 2004)

Disassembly of podosomes and the immune synapse

Limited work has been done investigating factors involved in the disassembly or turnover of PTAs and the immune synapse. However, substantial progress has been made in defining the mechanisms that regulate the turnover of the related adhesion structures, focal adhesions. Exogenous factors, such as the growth factor, EGF (Xie et al., 1998), or the ECM protein, thrombospondin (Orr et al., 2004), induce the disassembly of focal adhesions. These factors induce disassembly by modulating the activity of intracellular signaling proteins, including the intracellular calcium-dependent proteases, calpains. Calpains cleave several focal adhesion proteins, such as talin and FAK, and these proteolytic events have been implicated in the turnover of focal adhesions (Dourdin et al., 2001; Bhatt et al., 2002; Carragher and Frame, 2002). Specifically, proteolysis of talin is a rate-limiting step in focal adhesion turnover (Franco et al., 2004). There is evidence to suggest that similar mechanisms are involved in the turnover of PTAs. In dendritic cells, treatment with TNF-α and prostaglandin E has been linked to podosome disassembly (van Helden et al., 2006). Calpain is another regulator of podosome disassembly, since inhibition of calpain results in stabilization of podosomes in dendritic cells (Calle et al., 2006) and osteoclasts (Marzia et al., 2006). Several podosome components are calpain substrates including talin, Pyk2 and WASP (Calle et al., 2006; Perrin et al., 2006). However, the mechanism of calpain regulation of podosome disassembly remains unknown. In addition to proteolytic mechanisms other modes of regulation have emerged as key players in the disassembly of PTAs, including a role for regulated tyrosine phosphorylation by Src tyrosine kinases in the turnover of podosomes in osteoclasts (Luxenburg et al., 2006) and the activation of the Rho GTPase Cdc42 in the disassembly of macrophage podosomes (Linder et al., 1999).

The mechanisms that regulate the disassembly of the immune synapse and release of the T cell from the APC remain largely unknown. After a period of 8–12 hours of sustained contact between naïve T cells and dendritic cells, the cells dissociate and T cells resume migration (Mempel et al., 2004). Several hypotheses have been proposed connecting the completion of TCR-mediated signaling with immune synapse disassembly (Lee et al., 2003; Friedl et al., 2005); however, no one has shown how this may result in the depolarization of the actin cytoskeleton. Recently, observation of naïve T cell immune synapse formation on planar lipid bilayers has shown that cells undergo periods of synapse formation, disassembly and reformation regulated by PKCθ and WASP (Sims et al., 2007). T cells from PKCθ null mice fail to disassemble their immune synapse normally, indicating PKCθis likely an important regulator of disassembly.

Conclusion and perspectives

Despite their seemingly distinct functions, both podosomes and the immune synapse share a common ring-like morphology along with a number of structural regulators (Table 1). Recent progress suggests significant parallels between the regulatory mechanisms that contribute to the formation of these adhesive structures, and indicate that additional insight may be gained by further comparison of these structures. For instance, several known regulators of immune synapse formation, including the GEFs, Vav1 and DOCK2, have yet to be carefully studied in the context of podosome formation. Additionally, integrin-mediated signaling has been identified as a regulator of T cell activation (Perez et al., 2003) and actin polymerization (Suzuki et al., 2007), while more work is needed to investigate how integrin signaling may modulate podosomes. Furthermore, both in the context of the immune synapse and PTAs, we still have limited understanding of the basic mechanisms that regulate the turnover of these adhesive structures. The challenge for future investigation will be to unravel the key regulatory mechanisms that contribute to the integration and coordination of dynamic assembly and disassembly of these structures both in vitro and in vivo, and the implications of these mechanisms to normal physiology and human disease.

Table 1.

Components at podosomes, focal adhesions and immune synapses

| Component | Podosomesa | Focal adhesionsb | Immune synapses | References for immune synapse data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin nucleators | ||||

| Arp 2/3 | + | − | + | Krause et al., 2000 |

| Arp 2/3 regulators | ||||

| WAVE | − | − | + | Nolz et al., 2006 |

| WASP | + | − | + | Cannon and Burkhardt, 2004 |

| Cortactin/HS1 | + | − | + | Gomez et al., 2006 |

| Adhesion plaque components | ||||

| Vinculin | + | + | + | Nolz et al., 2007 |

| Talin | + | + | + | Monks et al., 1998 |

| Paxillin | + | + | + | Robertson et al., 2005 |

| Actin severing | ||||

| Gelsolin | + | − | ? | |

| Cofilin | + | − | + | Eibert et al., 2004 |

| Integrins | ||||

| β1 | + | + | + | Monks et al., 1998 |

| β2 | + | − | + | Mittelbrunn et al., 2004 |

| β3 | + | + | ? | |

Reviewed in (Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003)

Reviewed in (Wozniak et al., 2004)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ardouin L, Bracke M, Mathiot A, Pagakis SN, Norton T, Hogg N, Tybulewicz VL. Vav1 transduces TCR signals required for LFA-1 function and cell polarization at the immunological synapse. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:790–797. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcia C, Thomas CE, Curtin JF, King GD, Wawrowsky K, Candolfi M, Xiong WD, Liu C, Kroeger K, Boyer O, Kupiec-Weglinski J, Klatzmann D, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. In vivo mature immunological synapses forming SMACs mediate clearance of virally infected astrocytes from the brain. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2095–2107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals CR, Edwards AC, Gottschalk RJ, Kuijpers TW, Staunton DE. CD18 activation epitopes induced by leukocyte activation. J. Immunol. 2001;167:6113–6122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdeaux RL, Diaz B, Kim L, Martin GS. Active Rho is localized to podosomes induced by oncogenic Src and is required for their assembly and function. J. Cell Biol. 2004;166:317–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt A, Kaverina I, Otey C, Huttenlocher A. Regulation of focal complex composition and disassembly by the calcium-dependent protease calpain. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3415–3425. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.17.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billadeau DD, Nolz JC, Gomez TS. Regulation of T-cell activation by the cytoskeleton. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nri2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzaniti A, Neff L, Sanjay A, Horne WC, De Camilli P, Baron R. Dynamin forms a Src kinase-sensitive complex with Cbl and regulates podosomes and osteoclast activity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:3301–3313. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccione R, Orth JD, McNiven MA. Foot and mouth: podosomes, invadopodia and circular dorsal ruffles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:647–657. doi: 10.1038/nrm1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle Y, Carragher NO, Thrasher AJ, Jones GE. Inhibition of calpain stabilises podosomes and impairs dendritic cell motility. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2375–2385. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JL, Burkhardt JK. Differential roles for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein in immune synapse formation and IL-2 production. J. Immunol. 2004;173:1658–1662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman CV, Sage PT, Sciuto TE, de la Fuente MA, Geha RS, Ochs HD, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM, Springer TA. Transcellular diapedesis is initiated by invasive podosomes. Immunity. 2007;26:784–797. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher NO, Frame MC. Calpain: a role in cell transformation and migration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34:1539–1543. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellaiah MA. Regulation of podosomes by integrin alphavbeta3 and Rho GTPase-facilitated phosphoinositide signaling. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006;85:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellaiah M, Kizer N, Silva M, Alvarez U, Kwiatkowski D, Hruska KA. Gelsolin deficiency blocks podosome assembly and produces increased bone mass and strength. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:665–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT. Proteolytic activity of specialized surface protrusions formed at rosette contact sites of transformed cells. J. Exp. Zool. 1989;251:167–185. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402510206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coopman PJ, Thomas DM, Gehlsen KR, Mueller SC. Integrin alpha 3 beta 1 participates in the phagocytosis of extracellular matrix molecules by human breast cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:1789–1804. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryugina EI, Ratnikov B, Monosov E, Postnova TI, DiScipio R, Smith JW, Strongin AY. MT1-MMP initiates activation of pro-MMP-2 and integrin alphavbeta3 promotes maturation of MMP-2 in breast carcinoma cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;263:209–223. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourdin N, Bhatt AK, Dutt P, Greer PA, Arthur JS, Elce JS, Huttenlocher A. Reduced cell migration and disruption of the actin cytoskeleton in calpain-deficient embryonic fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48382–48388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dustin ML, Springer TA. T-cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Nature. 1989;341:619–624. doi: 10.1038/341619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibert SM, Lee KH, Pipkorn R, Sester U, Wabnitz GH, Giese T, Meuer SC, Samstag Y. Cofilin peptide homologs interfere with immunological synapse formation and T cell activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1957–1962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JG, Correia I, Krasavina O, Watson N, Matsudaira P. Macrophage podosomes assemble at the leading lamella by growth and fragmentation. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:697–705. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Teitelbaum SL, Fujikawa K, Chappel J, Zallone A, Tybulewicz VL, Ross FP, Swat W. Vav3 regulates osteoclast function and bone mass. Nat. Med. 2005;11:284–290. doi: 10.1038/nm1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco SJ, Rodgers MA, Perrin BJ, Han J, Bennin DA, Critchley DR, Huttenlocher A. Calpain-mediated proteolysis of talin regulates adhesion dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ncb1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, den Boer AT, Gunzer M. Tuning immune responses: diversity and adaptation of the immunological synapse. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:532–545. doi: 10.1038/nri1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui Y, Hashimoto O, Sanui T, Oono T, Koga H, Abe M, Inayoshi A, Noda M, Oike M, Shirai T, Sasazuki T. Haematopoietic cell-specific CDM family protein DOCK2 is essential for lymphocyte migration. Nature. 2001;412:826–831. doi: 10.1038/35090591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavazzi I, Nermut MV, Marchisio PC. Ultrastructure and gold-immunolabelling of cell-substratum adhesions (podosomes) in RSV-transformed BHK cells. J. Cell Sci. 1989;94:85–99. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez TS, McCarney SD, Carrizosa E, Labno CM, Comiskey EO, Nolz JC, Zhu P, Freedman BD, Clark MR, Rawlings DJ, Billadeau DD, Burkhardt JK. HS1 functions as an essential actin-regulatory adaptor protein at the immune synapse. Immunity. 2006;24:741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai CM, Hahne P, Harrington EO, Gimona M. Conventional protein kinase C mediates phorbol-dibutyrate-induced cytoskeletal remodeling in a7r5 smooth muscle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;280:64–74. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratsuka S, Watanabe A, Aburatani H, Maru Y. Tumour-mediated upregulation of chemoattractants and recruitment of myeloid cells predetermines lung metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1369–1375. doi: 10.1038/ncb1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GE, Zicha D, Dunn GA, Blundell M, Thrasher A. Restoration of podosomes and chemotaxis in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome macrophages following induced expression of WASp. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34:806–815. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaverina I, Stradal TE, Gimona M. Podosome formation in cultured A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells requires Arp2/3-dependent de-novo actin polymerization at discrete microdomains. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:4915–4924. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami N, Nagerl UV, Odoardi F, Bonhoeffer T, Wekerle H, Flugel A. Live imaging of effector cell trafficking and autoantigen recognition within the unfolding autoimmune encephalomyelitis lesion. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1805–1814. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempiak SJ, Yamaguchi H, Sarmiento C, Sidani M, Ghosh M, Eddy RJ, Desmarais V, Way M, Condeelis J, Segall JE. A neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein-mediated pathway for localized activation of actin polymerization that is regulated by cortactin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5836–5842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheir WA, Gevrey JC, Yamaguchi H, Isaac B, Cox D. A WAVE2-Abi1 complex mediates CSF-1-induced F-actin-rich membrane protrusions and migration in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:5369–5379. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M, Sechi AS, Konradt M, Monner D, Gertler FB, Wehland J. Fyn-binding protein (Fyb)/SLP-76-associated protein (SLAP), Ena/vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) proteins and the Arp2/3 complex link T cell receptor (TCR) signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:181–194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk C, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Sasaki T, Griffiths E, Ohashi PS, Snapper S, Alt F, Penninger JM. Vav1 controls integrin clustering and MHC/peptide-specific cell adhesion to antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2002;16:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Holdorf AD, Dustin ML, Chan AC, Allen PM, Shaw AS. T cell receptor signaling precedes immunological synapse formation. Science. 2002;295:1539–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.1067710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Dinner AR, Tu C, Campi G, Raychaudhuri S, Varma R, Sims TN, Burack WR, Wu H, Wang J, Kanagawa O, Markiewicz M, Allen PM, Dustin ML, Chakraborty AK, Shaw AS. The immunological synapse balances T cell receptor signaling and degradation. Science. 2003;302:1218–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.1086507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S. The matrix corroded: podosomes and invadopodia in extracellular matrix degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S, Aepfelbacher M. Podosomes: adhesion hot-spots of invasive cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:376–385. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S, Nelson D, Weiss M, Aepfelbacher M. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein regulates podosomes in primary human macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9648–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxenburg C, Parsons JT, Addadi L, Geiger B. Involvement of the Src-cortactin pathway in podosome formation and turnover during polarization of cultured osteoclasts. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:4878–4888. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchisio PC, Bergui L, Corbascio GC, Cremona O, D'Urso N, Schena M, Tesio L, Caligaris-Cappio F. Vinculin, talin, and integrins are localized at specific adhesion sites of malignant B lymphocytes. Blood. 1988;72:830–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzia M, Chiusaroli R, Neff L, Kim NY, Chishti AH, Baron R, Horne WC. Calpain is required for normal osteoclast function and is down-regulated by calcitonin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9745–9754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513516200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelbrunn M, Molina A, Escribese MM, Yanez-Mo M, Escudero E, Ursa A, Tejedor R, Mampaso F, Sanchez-Madrid F. VLA-4 integrin concentrates at the peripheral supramolecular activation complex of the immune synapse and drives T helper 1 responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11058–11063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307927101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi A, Hruska KA, Greenfield EM, Duncan R, Alvarez J, Barattolo R, Colucci S, Zambonin-Zallone A, Teitelbaum SL, Teti A. Osteoclast cytosolic calcium, regulated by voltage-gated calcium channels and extracellular calcium, controls podosome assembly and bone resorption. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:2543–2552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani K, Miki H, He H, Maruta H, Takenawa T. Essential role of neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein in podosome formation and degradation of extracellular matrix in src-transformed fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2002;62:669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 1998;395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SC, Yeh Y, Chen WT. Tyrosine phosphorylation of membrane proteins mediates cellular invasion by transformed cells. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119:1309–1325. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara H, Mueller SC, Nomizu M, Yamada Y, Yeh Y, Chen WT. Activation of beta1 integrin signaling stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of p190RhoGAP and membrane-protrusive activities at invadopodia. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara H, Maeda M, Tsuda M, Makino Y, Sawa H, Nagashima K, Tanaka S. DOCK2 mediates T cell receptor-induced activation of Rac2 and IL-2 transcription. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;296:716–720. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolz JC, Gomez TS, Zhu P, Li S, Medeiros RB, Shimizu Y, Burkhardt JK, Freedman BD, Billadeau DD. The WAVE2 complex regulates actin cytoskeletal reorganization and CRAC-mediated calcium entry during T cell activation. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolz JC, Medeiros RB, Mitchell JS, Zhu P, Freedman BD, Shimizu Y, Billadeau DD. WAVE2 regulates high-affinity integrin binding by recruiting vinculin and talin to the immunological synapse. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:5986–6000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00136-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross MA. A synaptic basis for T-lymphocyte activation. Ann. Immunol. 1984;135D:113–134. doi: 10.1016/s0769-2625(84)81105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr AW, Pallero MA, Xiong WC, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin induces RhoA inactivation through FAK-dependent signaling to stimulate focal adhesion disassembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48983–48992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez OD, Mitchell D, Jager GC, South S, Murriel C, McBride J, Herzenberg LA, Kinoshita S, Nolan GP. Leukocyte functional antigen 1 lowers T cell activation thresholds and signaling through cytohesin-1 and Jun-activating binding protein 1. Nat. Immunol. 2004;4:1083–1092. doi: 10.1038/ni984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin BJ, Amann KJ, Huttenlocher A. Proteolysis of cortactin by calpain regulates membrane protrusion during cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:239–250. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson LK, Mireau LR, Ostergaard HL. A role for phosphatidylinositol 3- kinase in TCR-stimulated ERK activation leading to paxillin phosphorylation and CTL degranulation. J. Immunol. 2005;175:8138–8145. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samelson LE. Signal transduction mediated by the T cell antigen receptor: the role of adapter proteins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:371–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.092601.111357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanui T, Inayoshi A, Noda M, Iwata E, Oike M, Sasazuki T, Fukui Y. DOCK2 is essential for antigen-induced translocation of TCR and lipid rafts, but not PKC-theta and LFA-1, in T cells. Immunity. 2003;19:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson WT, Franco SJ, Huttenlocher A. Talin1 regulates TCR-mediated LFA-1 function. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7707–7714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims TN, Soos TJ, Xenias HS, Dubin-Thaler B, Hofman JM, Waite JC, Cameron TO, Thomas VK, Varma R, Wiggins CH, Sheetz MP, Littman DR, Dustin ML. Opposing effects of PKCtheta and WASp on symmetry breaking and relocation of the immunological synapse. Cell. 2007;129:773–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somersalo K, Anikeeva N, Sims TN, Thomas VK, Strong RK, Spies T, Lebedeva T, Sykulev Y, Dustin ML. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes form an antigen-independent ring junction. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:49–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Yamasaki S, Wu J, Koretzky GA, Saito T. The actin cloud induced by LFA-1-mediated outside-in signals lowers the threshold for T-cell activation. Blood. 2007;109:168–175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-020164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Shoji S, Yamamoto K, Nada S, Okada M, Yamamoto T, Honda Z. Essential roles of Lyn in fibronectin-mediated filamentous actin assembly and cell motility in mast cells. J. Immunol. 1998;161:3694–3701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Hamano S, Gotoh K, Murata Y, Kunisaki Y, Nishikimi A, Takii R, Kawaguchi M, Inayoshi A, Masuko S, Himeno K, Sasazuki T, Fukui Y. T helper type 2 differentiation and intracellular trafficking of the interleukin 4 receptor-alpha subunit controlled by the Rac activator Dock2. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:1067–1075. doi: 10.1038/ni1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatin F, Varon C, Genot E, Moreau V. A signalling cascade involving PKC, Src and Cdc42 regulates podosome assembly in cultured endothelial cells in response to phorbol ester. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:769–781. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani S, Faccio R, Chandrasekar I, Ross FP, Cooper JA. Cortactin has an essential and specific role in osteoclast actin assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:2882–2895. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti A, Colucci S, Grano M, Argentino L, Zambonin Zallone A. Protein kinase C affects microfilaments, bone resorption, and [Ca2+]o sensing in cultured osteoclasts. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:C130–C139. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.1.C130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi S. Requirement for a complex of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) with WASP interacting protein in podosome formation in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2987–2995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner M, Billadeau DD. Vav proteins as signal integrators for multi-subunit immune-recognition receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:476–486. doi: 10.1038/nri840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tybulewicz VL. Vav-family proteins in T-cell signalling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2005;17:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valitutti S, Dessing M, Aktories K, Gallati H, Lanzavecchia A. Sustained signaling leading to T cell activation results from prolonged T cell receptor occupancy. Role of T cell actin cytoskeleton. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:577–584. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Helden SF, Krooshoop DJ, Broers KC, Raymakers RA, Figdor CG, van Leeuwen FN. A critical role for prostaglandin E2 in podosome dissolution and induction of high-speed migration during dendritic cell maturation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1567–1574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma R, Campi G, Yokosuka T, Saito T, Dustin ML. T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2006;25:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedham V, Phee H, Coggeshall KM. Vav activation and function as a rac guanine nucleotide exchange factor in macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced macrophage chemotaxis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4211–4220. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4211-4220.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb BA, Jia L, Eves R, Mak AS. Dissecting the functional domain requirements of cortactin in invadopodia formation. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2007;86:189–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AP, Wells CM, Smith SD, Vega FM, Henderson RB, Tybulewicz VL, Ridley AJ. Rac1 and Rac2 regulate macrophage morphology but are not essential for migration. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2749–2757. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak MA, Modzelewska K, Kwong L, Keely PJ. Focal adhesion regulation of cell behavior. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1692:103–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Pallero MA, Gupta K, Chang P, Ware MF, Witke W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Lauffenburger DA, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Wells A. EGF receptor regulation of cell motility: EGF induces disassembly of focal adhesions independently of the motility-associated PLCgamma signaling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:615–624. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Lorenz M, Kempiak S, Sarmiento C, Coniglio S, Symons M, Segall J, Eddy R, Miki H, Takenawa T, Condeelis J. Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:441–452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Pixley F, Condeelis J. Invadopodia and podosomes in tumor invasion. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006;85:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng R, Cannon JL, Abraham RT, Way M, Billadeau DD, Bubeck-Wardenberg J, Burkhardt JK. SLP-76 coordinates Nck-dependent Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein recruitment with Vav-1/Cdc42-dependent Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein activation at the T cell-APC contact site. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1360–1368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel PA, Bunnell SC, Witherow DS, Gu JJ, Chislock EM, Ring C, Pendergast AM. Role for the Abi/wave protein complex in T cell receptor-mediated proliferation and cytoskeletal remodeling. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]