Abstract

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is commonly used as a dietary supplement and may affect prostate pathophysiology when metabolized to androgens and/or estrogens. Human prostate LAPC-4 cancer cells with a wild type androgen receptor (AR), were treated with DHEA, androgens (DHT, T, or R1881), and E2 and assayed for PSA protein and gene expression. In LAPC-4 monocultures, DHEA and E2 induced little or no increase in PSA protein or mRNA expression compared to androgen-treated cells. When prostate cancer-associated (6S) stromal cells were added in coculture, DHEA stimulated LAPC-4 cell PSA protein secretion to levels approaching induction by DHT. Also, DHEA induced 15-fold more PSA mRNA in LAPC-4 cocultures than in monocultures. LAPC-4 proliferation was increased 2–3 fold when cocultured with 6S stromal cells regardless of hormone treatment. DHEA-treated 6S stromal cells exhibited a dose- and time-dependent increase in T secretion, demonstrating stromal cell metabolism of DHEA to T. Coculture with non-cancerous stroma did not induce LAPC-4 PSA production, suggesting a differential modulation of DHEA effect in a cancer-associated prostate stromal environment. This coculture model provides a research approach to reveal detailed endocrine, intracrine, and paracrine signaling between stromal and epithelial cells that regulate tissue homeostasis within the prostate, and the role of the tumor microenvironment in cancer progression.

Keywords: DHEA, stromal, prostate, PSA, coculture

1. Introduction

DHEA, the most abundant endogenous adrenal steroid produced by men and women, declines markedly with aging [1]. It is increasingly consumed as an over-the-counter dietary supplement for its purported antiaging effects, yet its usefulness, long-term safety and effects on prostate tissues remain uncertain [2]. Prostate stromal and epithelial cells possess the enzymatic machinery to metabolize DHEA to more active androgenic and/or estrogenic steroids[3–5] (intracrine) and express secondary mediators (paracrine) for epithelial growth and differentiation. Defining DHEA and other steroid hormonal responses in the prostate requires simulation of the intracrine and paracrine effects of hormones provided by stromal cells. Interactions between stromal and epithelial cells in hormone responsive tissues are increasingly recognized as an important area of research highlighted for many diseases, especially cancer [6].

As a precursor to both estrogens and testosterone, DHEA excess may pose a potential cancer risk in hormone-responsive tissues such as the prostate. Different prostate cell types display distinct responses to DHEA. For example, human prostate cancer LNCaP cells, which harbor a mutated androgen receptor (AR), respond to DHEA administration with increased proliferation, and expression of prostate specific antigen (PSA) and IGF axis proteins[7]. Human prostatic primary stromal cells respond to androgens, such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT), but not DHEA, by increasing IGF-I secretion [8]. Contrastingly, in in vivo studies, DHEA has been found to be an effective inhibitor to carcinogen-induced prostate cancers [9]. In the current study, we examined the effects of DHEA on proliferation and PSA production in human prostate cancer LAPC-4 cells, which contain a normal AR, in both monoculture and in coculture with stromal cells from normal or cancer-related tissues. This cell coculture model provides an opportunity to investigate the intracrine and paracrine stromal mediators of hormonal responses in epithelial cells and demonstrates the importance of prostate stromal cells in mediating the response of prostate epithelial cells to DHEA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell Culture

LAPC-4 cells were derived from lymph node metastases of staged prostate cancer patient [10] and were generously provided by Dr. Charles Sawyers, UCLA. Primary human prostate cancer-derived stromal cells were isolated from radical prostatectomy specimens ([11]; cell lots from different patient samples were labeled: 5S, 6S, 9S, and 12S; kindly provided by Dr. John Isaacs, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) and have been previously described [8]. Primary prostate stroma cells (PRSC) derived from normal prostate tissues, were obtained from Cambrex (East Rutherford, NJ). All cell types were grown in DMEM:F12 (1:1) medium, (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD) with penicillin (100 units/mL), streptomycin (100 µg/mL), L-glutamine (292 µg/mL) (Invitrogen), and 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, HyClone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT) at 37°C in 5% CO2 and propagated at 1:5 dilutions. Cells were kept as frozen stocks and used between passages 5 and 12‥ All experiments were performed in Treatment Media consisting of Medium 199 (phenol red-free): F12 phenol red-reduced media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) (1:1) supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml), glutamine (100 mg/ml; Invitrogen) and 2% charcoal-dextran-treated FBS (CDS—Hyclone Labs)

2.2 LAPC-4 Monoculture PSA Protein Determination By ELISA

LAPC-4 cells were plated at 5×105 in triplicate in 24 well dishes, in 1mL/well of Treatment Media (as above). Cells were cultured in this media for 3 days, to allow for down-regulation basal hormonal activity. Cells were then treated with vehicle control, DHEA, DHT, T, or E2, at 0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, and 1000 nM in Treatment Media with CDS added at 1% to further reduce serum factors. Doses were chosen based on previous studies using these hormones in LNCaP cells [7] and on normal physiological hormonal levels in serum of men from ages 40 – 80 years [12] as well as bio-available levels achieved by supplementation [13]. After 3 days, media with hormone was replaced and allowed to condition for 48 hours [7]. Conditioned media from each well was collected, aliquoted and stored at −80°C for ELISA analysis. Total PSA ELISA kits (DSLabs, Webster, TX) were used to determine PSA concentrations as previously reported [7]. Each original triplicate experimental sample was assayed in duplicate. PSA values were normalized to cell numbers as determined by the modified MTT assay [7].

2.3 Monoculture PSA Gene Expression

Cells were plated in triplicate at 1.5×106 per well of 6 well plate in 1.5mL of Treatment Media. After 3 days, cells were treated with vehicle control, 0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1000 nM (1.5 mL solution/well) for each of 4 hormones: DHEA, DHT, T, and E2 in Treatment Media with a final concentration of CDS at 1%. After 48 hours, media was aspirated from all wells and 1.5 mL of Trizol was used for RNA extraction. Real-Time PCR of PSA vs RPLPO was performed as described previously [7].

2.4 PSA ELISA For Cocultured Cells

LAPC-4 cells were seeded in Treatment Media with 2% CDS as above in triplicate onto Millipore PICM 12mm inserts (Billerica, MA) coated with a 1:10 dilution of Matrigel ™ (BD Biosciences Bedford, MA) :H2O, at a density of 5×105 cells/well. Parallel cultures of stromal cells (6S) cells were seeded in triplicate at 1×105 / well in 24 well plates, in Treatment Media.with 2% CDS LAPC4 and 6S cells were grown separately for 2 or 3 days. Cocultures were initiated by placing inserts containing epithelial cells into wells containing stromal cells thus allowing secreted factors from either cell to pass through pourous membrane of insert. Hormones were added in Treatment Media with the reduced level of 1% CDS plus 0, 10, 100 or 1000 nM DHEA, 10nM DHT, 10 nM R1881 and 100 nM E2, and allowed to coculture for 3 days. Media containing hormones was replaced and allowed to condition for 48 hours. Conditioned media were collected and frozen at −80 C or assayed directly as above Values were corrected for relative cell numbers as estimated using the CellTiter 96® Assay (MTT assay) (Promega, Madison WI), as previously described [7].

2.5 Coculture PSA RNA Determination

Cocultures were prepared as above with LAPC-4 seeded in triplicate in 30mm inserts pre-coated with Matrigel film at a density of 2×106 cells/6 well and 6S cells plated onto a 60 mm dish, using Treatment Media as described above. After 2–3 days, inserts containing epithelial cells were added to plates containing stromal cells and cocultures were treated with 100nM DHEA and E2, 10 nM DHT, for 2 days. RNA was extracted from cell cultures using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Methods for RNA extraction, reverse transcription, realtime PCR, as well as primers for RPLPO and PSA were previously described [7].

2.6 Coculture Cell Proliferation Assays

LAPC-4 cells were seeded at 106 cells per mL of Treatment Media. Cells were plated in triplicate on Millipore PICM 30mm inserts (Billerica, MA) coated with a 1:10 dilution of Matrigel™:H2O. Primary prostate (6S) stromal cells were seeded in triplicate at 5×105/60 mm tissue culture plastic dish. After 3 days, inserts containing the LAPC-4 cells were added to the 60 mm dish of stromal cells, and hormones were added in Treatment Media with 1% CDS at 0, 100 nM DHEA, 10 nM DHT or 10 nM R1881 and allowed to coculture for 3 days. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and counted using a Beckman Coulter counter.

2.7 Stromal Testosterone ELISA Assays

Stromal cells (6S or PRSC) were plated at 5 × 104 cells per well in triplicate in 24 well plates and pretreated with Treatment Media for 2 days. DHEA was added at concentrations ranging from` 0.1 to 10,000 nM, for 5 days or at 100 nM for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. Conditioned Media was collected and assayed for testosterone (T) by ELISA (DSLabs, Webster, TX). Values were corrected for relative cell numbers as estimated using the CellTiter 96® Assay (MTT assay) (Promega, Madison WI), as previously described [7]. As per manufacturer protocol, there is no cross-reactivity for DHEA in this assay.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean values ± SEM derived from 3 to 8 replicates within each of three separate experiments. To delineate effects of hormone, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using the Tukey-Kramer HSD adjustment for multiple comparisons. In order to compare values within the same treatment groups, Student t-tests were performed. An adjusted P-value of 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1 DHEA effects on LAPC-4 PSA protein expression in monoculture

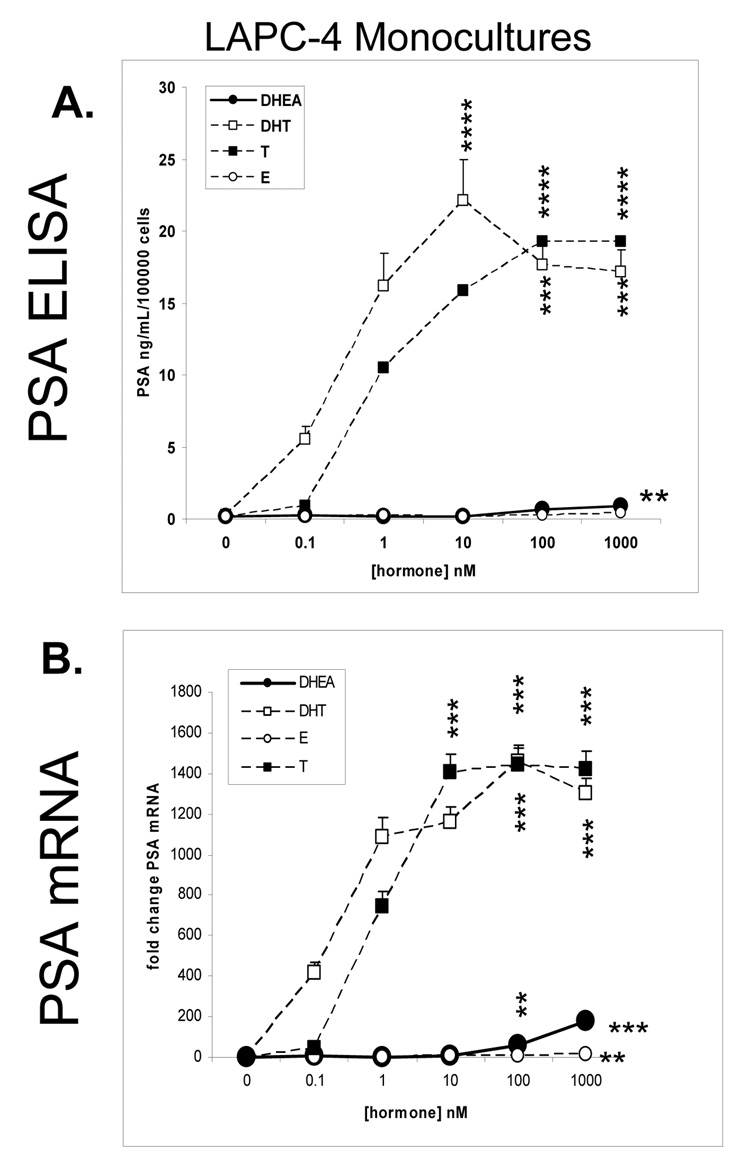

PSA secretion or expression was used as a biomarker for prostate epithelial cell response to androgenic hormones. LAPC-4 cells were assayed for PSA protein expression by ELISA in response to DHEA, compared to DHT, T and E2. The androgens, DHT and T induced PSA production in a dose dependent manner with the maximal effect of 22 ng/ml/100,000 cells at 10 nM DHT and of 19 ng/ml/100,000 cells at 100 nM T (Figure 1A, P< 0.0001). DHEA and E2 induction of PSA were minimal and only at 1000nM (0.88 and 0.4 ng/mL/100,000 cells respectively P<0.01).

Figure 1. PSA gene and protein expression in LAPC-4 cells in monoculture.

A. PSA protein determination by ELISA

Cells were plated in triplicate at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well in 24 well dishes, in 1mL of Treatment Media. After 3 days, cells were treated with control DHEA, DHT, T, and E2, at 0.1nM, 1nM, 10nM, 100nM, and 1000nM in Treatment Media with a final concentration of CDS at 1%. After 3 days, media with hormone was replaced and allowed to condition for 48 hours. Conditioned media was collected and assayed by ELISA for PSA concentrations. Cell numbers were estimated using the MTT assay scaled to a 24 well format. Graphs illustrate mean ± SD values of PSA, averaged from three experiments.

B. PSA gene expression determination by Real Time RT-PCR

LAPC-4 cells were plated in triplicate in 6 well plates at a density of 2 × 106 cells/well, in Treatment Media for 3 days prior to treatment with control, DHEA, DHT, T, or E2 at same doses as above. RNA samples were extracted, reverse transcribed and assayed for PSA gene expression by Real Time PCR and expressed as fold change PSA mRNA. Graphs illustrate mean ± SD values averaged from three experiments.

3.2 DHEA effects on PSA gene expression in LAPC-4 cells in monoculture

PSA mRNA expression was assayed by real-time RT-PCR in LAPC-4 cells after 48 hours treatment with DHEA, DHT, T or E2. (Figure 1B). The androgens, DHT and T induced PSA gene expression in a dose dependent manner, with the maximal effect of about 1450-fold change over control at 100 nM, respectively (P< 0.001). DHEA induction of PSA peaked at 1000 nM at one tenth the level of the androgens (176 fold change P< 0.001). E2 induction was statistically significant, but substantially less, as 1000 nM induced a 16 fold increase over control (P<0.01).

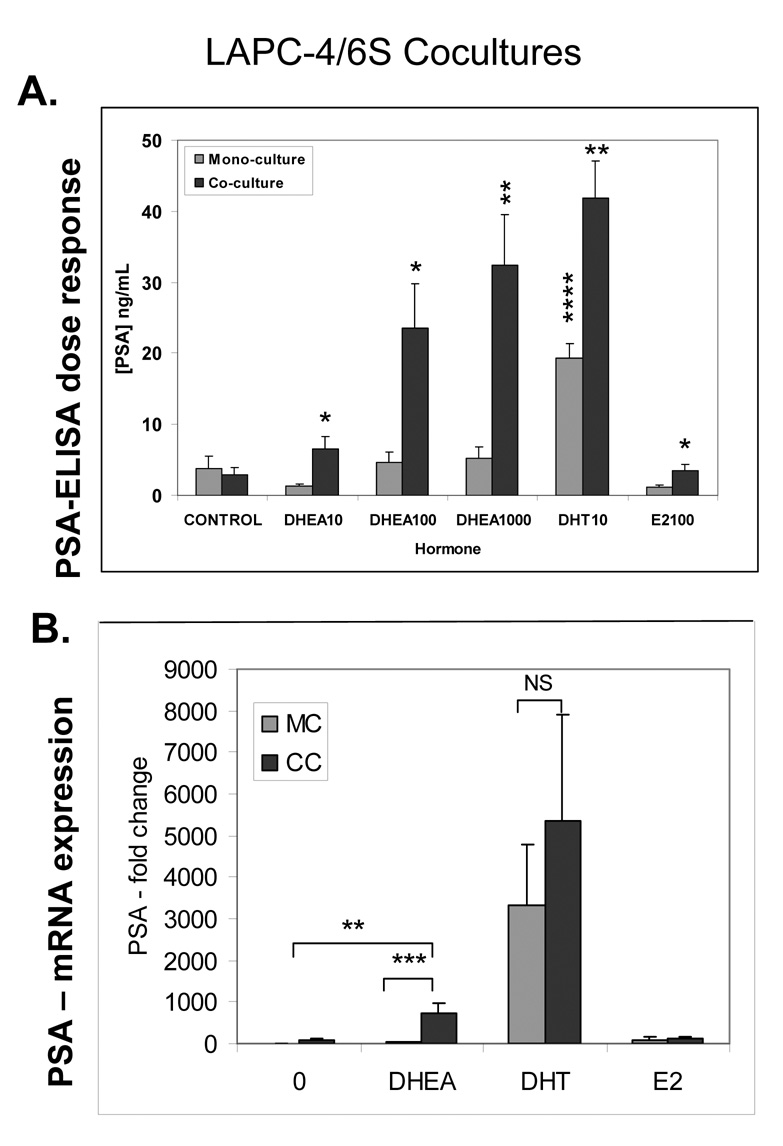

3.3 Prostate stromal induction of LAPC-4 PSA protein production

When 6S stromal cells were added to LAPC-4 cells in coculture, the LAPC-4 cells exhibited a significant, dose dependent increase in PSA protein secretion in response to DHEA concentrations (Figure 2A) ranging from 10 to 1000 nM (6, 24, and 32 ng/mL) (P<0.05), reaching or exceeding levels induced by DHT in monoculture. LAPC-4 monocultures treated with the same concentrations of DHEA showed no significant change in PSA production. PSA levels were also higher in DHT-treated LAPC-4 cells in coculture compared to monoculture (42 vs. 19 ng/ml, P<0.05). In cocultures, estrogen exposure induced small but significant increase over E2-treated monocultured LAPC-4 but not over control treated mono or cocultures.

Figure 2. Prostate stromal effects on LAPC-4 PSA protein and gene expression.

A. Prostate stromal induction of LAPC-4 PSA protein production

Cocultures of LAPC-4 cells and 6S stromal cells were prepared. LAPC-4 cells were seeded in triplicate onto Millipore PICM 12mm inserts coated with a film of Matrigel at a density of 5×105 cells/well. Stromal cells (6S) cells were seeded in triplicate at 1×105 / well of 24 well plates. Cells were grown separately in media containing 2% CDS for 2 or 3 days prior to combining in coculture and addition of DHEA (10, 100 or 1000 nM) DHT (10 nM) and E2 (100 nM) and were incubated for 3 days. Media containing hormones was replaced and allowed to condition for 48 hours. Conditioned media were collected assayed by ELISA for free PSA. Cell numbers were estimated using the MTT assay scaled to a 24 well format. Assay was performed three times and mean and SE are represented.. P values are represented as follows: **** P<0.0001,, ** P<0.01, *P<0.05

B. Prostate stromal induction of LAPC-4 PSA gene expression

LAPC-4 cells were seeded in triplicate 30mm inserts pre-coated with Matrigel film at a density of 2×106 cells/insert. 6S cells were plated on 60 mm dish at 5×105 / dish. After 2–3 days, cells were combined and treated with 100nM DHEA, 100nM E2, or 10 nM DHT for 2 days, and then harvested to extract RNA and perform reverse transcription and realtime PCR. Assay was performed three times and mean and SE are represented. Graphs illustrate mean ± SD values averaged from three experiments performed in triplicate. P values are represented as follows: *** P<0.001, ** P<0.01.

3.4 Prostate stromal induction of LAPC-4 PSA gene expression

Addition of stromal cells also augmented PSA mRNA expression in DHEA-treated 6S/LAPC-4 cocultures (Figure 2B). DHEA-treated LAPC-4 cells in coculture with 6S cells produced 18 times more PSA than cells in monoculture (713 vs. 39 fold change; P < 0.0001). The increase in PSA in DHT-treated cocultures was significant within each experiment, but significance was lost due to the variation in fold change between all three experiments. E2 had no effect on LAPC-4 PSA mRNA expression.

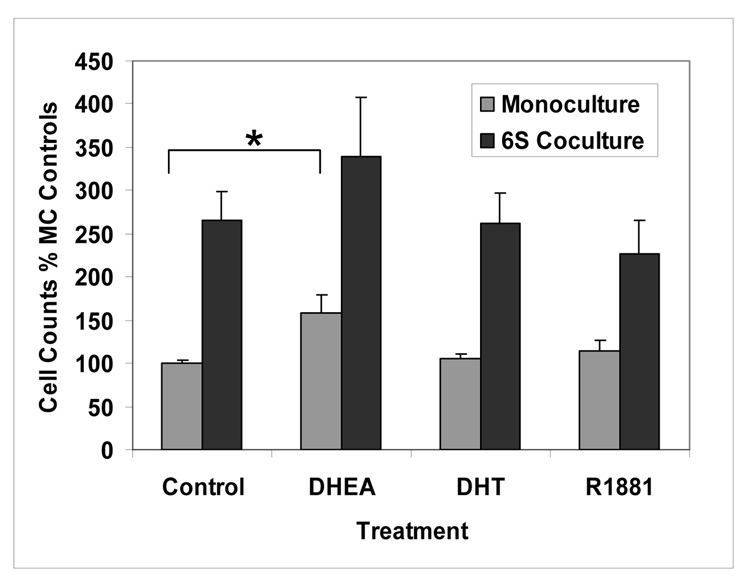

3.5 Stromal cell effects on of LAPC-4 cell proliferation

The effect of 6S stromal cells on LAPC-4 cell proliferation was evaluated following 3 days of steroid hormone treatment. A modest increase in proliferation was seen in DHEA-treated monocultured cells compared to control (1.6 fold; P<0.01), but in no other hormone treatments of monocultured cells. LAPC-4 cells that were cocultured with 6S stromal cells showed 2.0 to 2.6 fold increase in proliferation over that in LAPC-4 cells cultured alone (Figure 3, P<0.05); but no additional significant effects on proliferation from the hormones, DHEA, DHT or R1881 were found.

Figure 3. Hormone effects on LAPC-4 Cell Proliferation in monoculture and coculture: LAPC-4 proliferation is increased in coculture with 6S primary prostate stromal cells.

LAPC-4 cells were seeded at 106 cells per Matrigel-film-coated 30mm insert. Primary prostate (6S) stromal cells were seeded in triplicate at 5×105 / 60 mm tissue culture plastic dish. After 3 days, inserts containing the LAPC-4 cells were added to the 60 mm dish of stromal cells and hormones were added at 0, 100nM DHEA, 10nM DHT or 10 nM R1881 and allowed to coculture for 3 days. LAPC-4 cells were harvested by trypsinization and counted using a Beckman Coulter counter. Cell counts are expressed as percentage of the monoculture control. Assay was performed three times and means and SE are represented, *P<0.01.

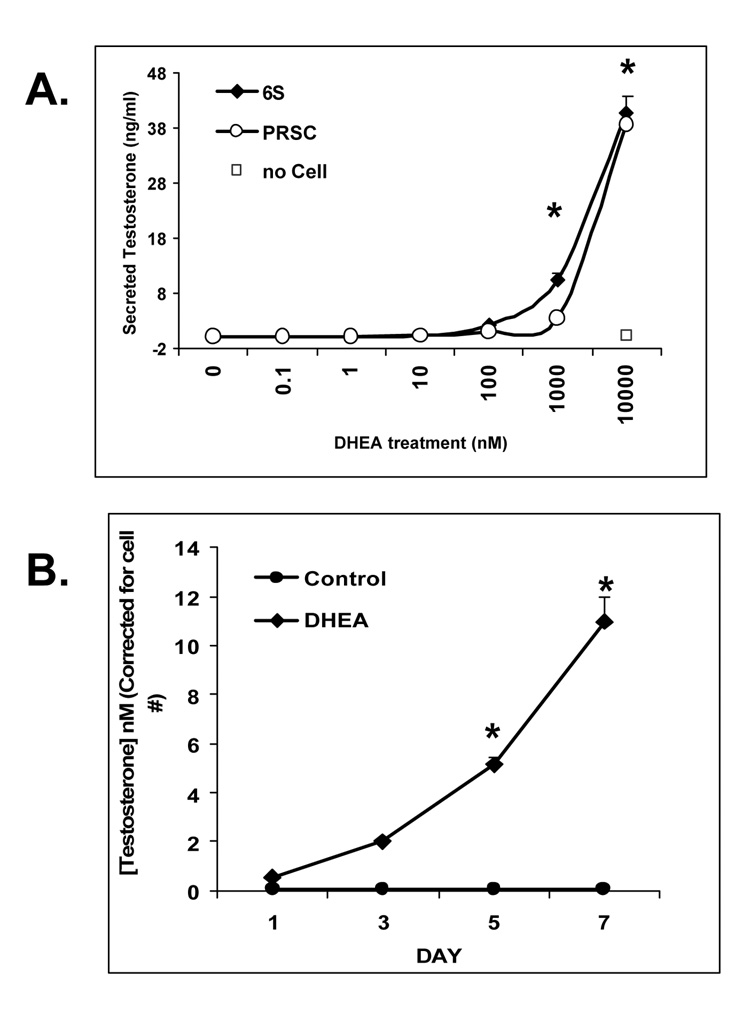

3.6 Stromal cell metabolism of DHEA to testosterone

To determine the ability of the cancer-associated 6S and normal PRSC prostate stromal cells to metabolize DHEA to testosterone, stromal cells were treated with DHEA and assayed for testosterone production by ELISA. Cells were treated with DHEA at concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 10,000 nM for 5 days to assess dose response or at 100 nM for 1, 2, 5, or 7 days for time response (6S only). Increasing amounts of testosterone were detected by ELISA from conditioned media of stromal cells treated with DHEA at 1000 and 10,000 nM with up to 40 ng/mL testosterone released (Figure 4A; P< 0.05). A “no cell” control was included consisting of media containing highest dose of DHEA without cells to monitor potential T levels in media alone. Over time, testosterone was increased in 6S cells with 100 nM DHEA treatment after 3, 5 and 7 days culture (Figure 4B) with values peaking at 10 nM T production (P<0.05)after 7 days DHEA treatment.

Figure 4. Stromal Cell Metabolism of DHEA to Testosterone:DHEA-treated primary 6S and PrSC stromal cells increase T secretion in a dose and time dependent manner.

Stromal cells (6S or PrSC) were plated in triplicate in 24 well plates and pretreated with Treatment Media for 2 days. (A). Dose response; DHEA was added at doses 0.1 to 10,000 nM, for 5 days. B. Time response; Cells treated with control of no hormone or DHEA at 100 nM for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. Conditioned Media was collected and assayed for testosterone by ELISA. T values were corrected for cell number by running a parallel MTT assay. Assay was performed three times and mean and SE are represented.

3.7 LAPC-4 PSA production when cocultured with different stromal cell lots

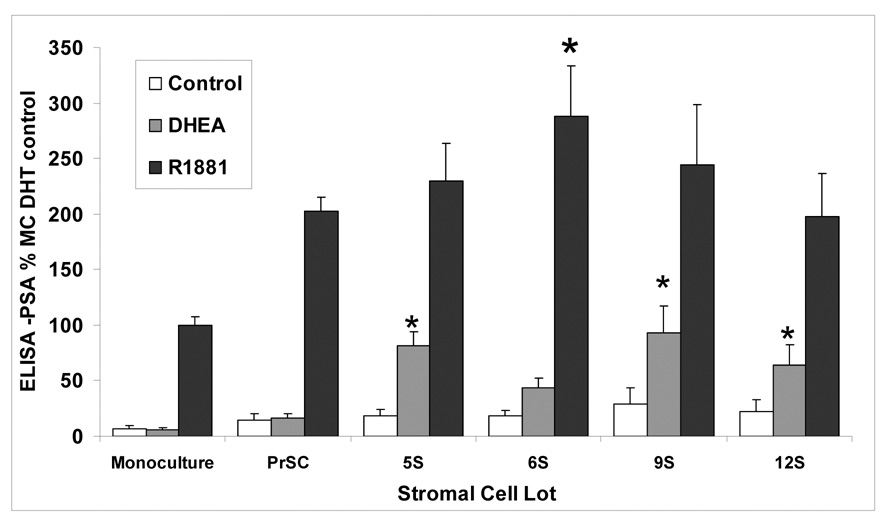

DHEA-induced LAPC-4 PSA production was compared in cocultures with stromal cells derived from normal prostate tissue (PRSC) and from prostate cancer surgery samples (5S, 6S, 9S, 12S). DHEA-treated LAPC-4 cells cocultured with 5S, 6S, 9S, and 12S increased PSA secretion from 8 to 17 times compared with PSA production in monocultured LAPC-4 cells (Figure 5, P< 0.05). In contrast, LAPC-4/PRSC cocultures produced no significant increase in PSA production compared with LAPC-4 monocultures.

Figure 5. Effects of various stromal cell lots on LAPC-4 PSA Level induced by DHEA and R1881 compared with effects in monocultured LAPC-4 cells.

Coculture assays for ELISA determination of LAPC-4 PSA were prepared as before using stromal lots 5S, 6S, 9S, 12S, or PrSC. Hormones were added at 100nM DHEA treatment or (10nM) R1881. Values are represented as percent change in LAPC-4 PSA level induced by various stromal cells. Assay was performed three times and mean and SE are represented (*P< 0.05 compared to MC same hormone treatment).

4. Discussion

This study provides a physiologically relevant in vitro endocrine (DHEA)-paracrine (stroma-mediated) reproduction of human prostate stromal cell induction of proliferation and PSA production in epithelial cancer cells. The data also support a mechanism of DHEA effects in prostate that would not be ascertained using single cell cultures alone. DHEA treatment did not affect prostate epithelial cells PSA production when cultured alone but produced an androgenic response in epithelial cells in the presence of stromal cells from cancerous tissues. The data further suggests that potential differences in the prostate microenvironment could alter DHEA metabolism to androgens or estrogens, leading to subsequent effects on prostate physiology and cancer progression.

DHEA and it’s sulfated form, DHEAS, are present in adult men and women at serum levels 100 to 500 times higher than those of testosterone and 1000 to 10,000 times higher than those of estradiol but levels decrease up to 80% with age [1,14,15]. DHEA is widely used as an over-the-counter dietary supplement with unsubstantiated claims of beneficial effects on body composition, cardiometabolic, immune, and neurobiological functions [16] as well as uncertain long-term safety. Humans and other primates are unique among animal species in that their adrenal glands secrete large amounts of DHEA and DHEA-S [5,12]. DHEA has been shown to exert many of its effects via the AR and/or estrogen receptor (ER) following its enzymatic conversion to androgen or estrogen [17], although direct effects of DHEA on the AR and ER have also been demonstrated [18–21]. DHEA can act as a direct ligand for the ERβ [18] or can be metabolized to estrogenic ligands including 3β Adiol, E2, or 7- hydroxy DHEA [22]. Moreover, DHEA can act via non-steroid receptor, non-genomic pathways, as shown in vascular endothelial cells [23]. In aged adults, the use of DHEA as a dietary supplement is of potential concern in that its androgenic or estrogenic metabolites may have adverse effects on cancer cells within the prostate or breast.

A prostate stromal/epithelial cell coculture model was developed to investigate the importance of stromal cells in the epithelial cell response to DHEA. The prostatic primary stromal cells used in this study (6S) were previously found to increase expression of IGF-1 and IGFBP2 and decrease IGFBP3 in response to treatment with DHT but not with DHEA [8]. The current study focuses on DHEA effects on LAPC-4 cells which, like normal (non cancerous) prostate luminal cells, contain a wild type AR [10]. LAPC-4 cells were grown on a film of Matrigel in a filter insert separated from the stromal cells growing on the plastic below. The ratio of stromal cells to epithelial cells remained at 1:4 or 1:5. Matrigel basement membrane proteins were included to assist attachment of cells to the Millicell inserts and to better reproduce the epithelial cellular physiological microenvironment [24,25]. When grown on the Matrigel film, the LAPC-4 cells clustered together in a three dimensional multilayered configuration, connected by bridges of cells (data not shown). Doses of DHEA and other hormones used throughout the study were chosen based on previous studies [7]. The DHEA dose is similar to normal physiological hormonal levels in serum of men from ages 40 – 80 years [12] as well as bio-available levels achieved by supplementation [13]. While LAPC-4 cells are androgen responsive in growth in vivo [26] or in other cell models [10], the current study did not document a strong proliferative response to the steroid hormones. However, the proliferative response of LAPC-4 to the presence of stromal cells, regardless of the hormone treatment, was significant with 2–3 fold increases in cell numbers within 3 days, similar to prior results published in normal or cancer prostate cells [27]. Multiple stromal cell secreted growth factors may contribute to this proliferative effect, including IGF-1, EGF, HGF, KGF, FGF [8,28–31], as well as nvolvement of extracellular matrix proteins [25].

In contrast to the minimal proliferative response to hormones, LAPC-4 PSA production was highly sensitive to androgenic stimulation. PSA protein and gene expression as assess by ELISA and real time RT-PCR was used as a measure of androgenic activity. While the effects of DHEA on LAPC-4 and 6S stromal cells grown separately were minimal, an important mechanism of DHEA effects on prostate was highlighted when these cells were grown together in coculture. LAPC-4 cells displayed a dramatic increase in proliferation and PSA protein and gene expression in the presence of stromal cells. Only soluble paracrine factors are implicated in this interaction, as cells were separated by a filter, yet shared the same media.

The mechanism of stromal induction of PSA by DHEA could be due to stromal cell metabolism of the DHEA towards more androgenic ligands as demonstrated by increased T measured in media of stromal cells treated with DHEA. The testosterone (or DHT) could diffuse through the insert and directly activate the AR in the LAPC-4 cells to induce PSA production. The metabolic pathways from DHEA to DHT involves multiple enzymes, including 3β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) 1 and 2, and 17B HSD 1, 3, and 5 [17]. Current studies are underway to determine role of 3β and 17β HSD’s separately and combined in contributing to stromal role in metabolism of DHEA.

After 48 hour hormone treatment, the transcriptional induction of PSA expression in cocultures may be due to stimulation by DHEA steroid metabolites plus secondary stromal mediators (andromedins), as evidenced by increased PSA expression in cocultures treated with R1881, a non-metabolizable androgen. These factors include those listed above for proliferation, as well as the bidirectional interchange of signals between stromal and epithelial cells that are seminal in regulating tissue homeostasis, also the loss of which may contribute to progression of prostate cancer [32].

Both normal stroma (PRSC stromal cells derived from healthy, non-diseased prostate) and cancer-associated stromal cells (6S) treated with DHEA were shown to secrete testosterone. But LAPC-4 cells cocultured with PRSC did not increase DHEA-induced PSA production as did the stromal cell lots from prostate cancer surgical samples, (labeled 5S, 6S, 9S, and 12S for the isolation lot number (5,6, 9 or 12) and S for “stroma”). These latter stromal cell lots have been previously characterized as having differential capacity to produce IGF-I, IGFBP-2 and IGFBP-3 [8] as well as having differential expression of cytoskeletal proteins which define the continuum from normal stroma to reactive stromal phenotypes [8,33]. While the enzymatic/metabolic capacity may be similar in PRSC and reactive stromal cells, there may be additional or different secondary paracrine factors induced in the reactive cancer stroma beyond metabolism of the DHEA that is involved in PSA production. Identification of these paracrine mediators of increased PSA expression are the subject of continued studies.

This laboratory has also shown that DHT-treated normal prostate epithelial (NPE) cells in coculture with reactive stromal cells (NPE/6S) were more resistant to campothecin-induced cell death, whereas NPE/PRSC cocultures exhibited campothecin - induced cell-death regardless of DHT treatment, underscoring discernable differences between these stromal populations in cocultures [34] The data represented in this paper further delineate possible phenotypic differences found in normal stroma vs. reactive stroma or cancer-associated stroma and leads to a hypothesis for DHEA effects on prostate.

Based upon these findings, we propose a hypothesis that DHEA exerts minimal effects on normal prostate but in cancer-associated tissues, a reactive stromal microenvironment can promote prostate proliferation or PSA production in the presence of DHEA via stromal metabolism to androgenic metabolites and induction of secondary reactive stromal paracrine growth factors. This hypothesis is supported by literature describing the initial pre-neoplastic lesions of prostate cancer of prostatic inflammatory atrophy (PIA), as a reactive stromal environment with infiltration of immune cells and increased presence of cytokines [39]. Increased 3β-HSD type 1 gene expression has been found in the presence of cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 [17], When the prostate is in an inflammatory state, such as in PIA, the endogenous DHEA may be promoted towards androgenic metabolism, promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis. If the prostate is in a normal, non-reactive state, high DHEA levels may not only provide a ‘hormonal buffer’ [40] but also be metabolized to estrogenic ligands which, acting through the ERβ, may attenuate AR effects, thus maintaining balance between androgenic and estrogenic signals. The microenvironment of the prostate may dictate the ultimate fate of DHEA metabolism towards androgenic or estrogenic ligands. This is important, not only in consideration of DHEA used as a dietary supplement, but in also in determining physiological role of DHEA in prostate.

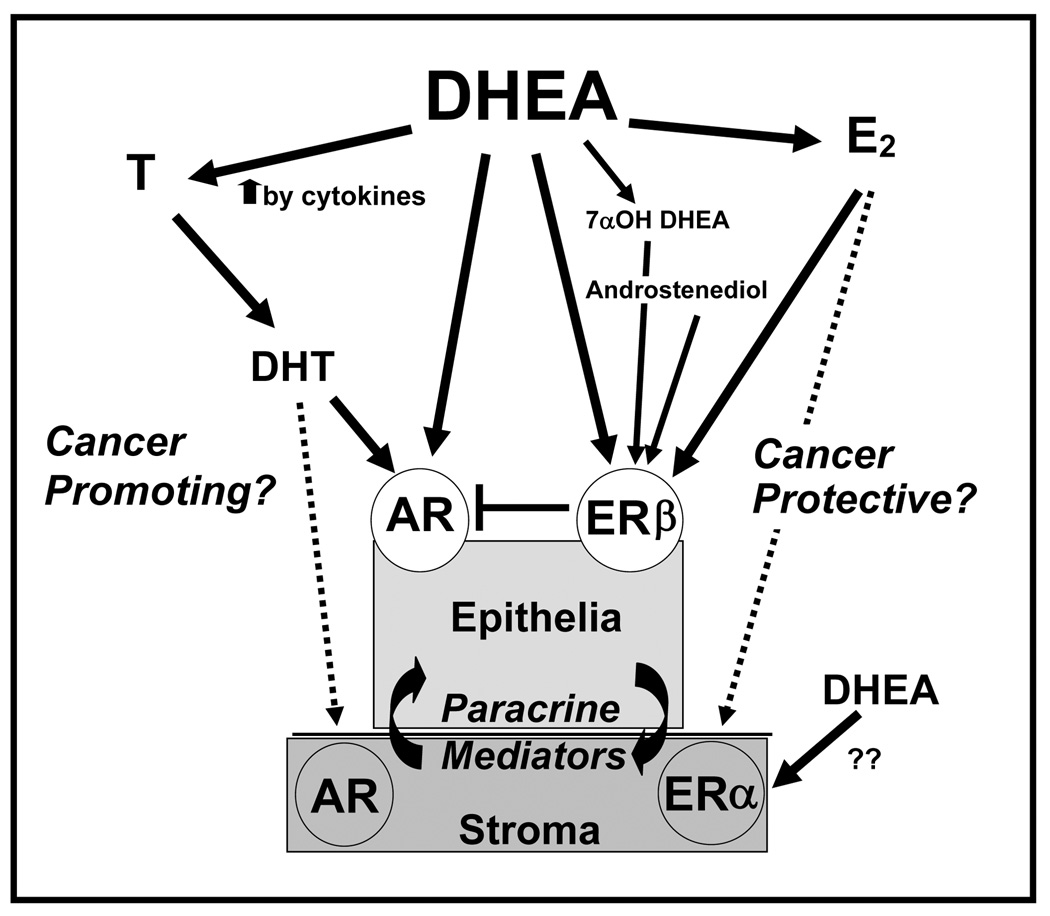

The complexity of the prospective effects of DHEA in prostate tissues is represented in Figure 6, It includes such contributing factors as 1- the possible metabolism of DHEA to androgenic or estrogenic ligands; 2- the potential cytokine contribution to increased steroid metabolism; 3- the stromal and epithelial cell components including their cross-talk, 4- the AR and ERβ (or ERα in stromal cells) and downstream effectors; 5- the hormone-induced paracrine signaling; and 5-the importance of the stromal component as a basis for the differences in the metabolism of DHEA. The question of whether DHEA can be cancer promoting or cancer preventive continues to be debated. [21].

Figure 6. Endocrine- Intracrine- Paracrine- model of interactions between prostate stromal and epithelial cells affecting the pathways of DHEA metabolism in prostate tissues.

The complexity of the effects of DHEA in prostate tissues includes metabolism of DHEA to androgenic or estrogenic ligands, the potential cytokine contribution to increased DHEA metabolism, both stromal and epithelial components, the expression of AR and ER β or (ERα in stromal cells) and their downstream effectors, the hormone-induced paracrine signaling and shows the importance of the stromal component as a contributor to DHEA metabolism. Androgenic ligands may promote progression to cancer by increasing growth, IGF axis and PSA production. Conversely, the estrogenic ligands, mediated by ER beta may protect from cancer by antagonizing androgenic pathways. Each of these factors plays an important role in defining the effects of DHEA on the prostate. These factors can be manipulated in the co-culture model provided to determine DHEA mechanisms as well as elucidate paracrine -intracrine - endocrine prostate stromal-epithelial signals important in responses to hormones.

This coculture model is important for its potential to identify intracrine and paracrine stromal mediators of DHEA effects on epithelial cells, especially since DHEA had little effect on LAPC-4 in the absence of the stroma. Other experimental prostate models of androgen regulation of stromal-epithelial signaling [35–38] or intracrine production of DHEA metabolites (ERβ ligand 7α-hydroxy DHEA) [22] have been described. The coculture model presented herein also provides an opportunity to elucidate the role of the tumor microenvironment in cancer progression by comparing responses of epithelial cells to normal vs. reactive stromal cells. However, the model does not allow for elucidation of possible effects of direct stromal–epithelial cell contact. Moreover as an in vitro model, it cannot provide data on all the complex physiological regulatory mechanisms inherent in in vivo models.

This coculture protocol is valuable for efficacy and mechanistic testing of natural, botanical or synthetic agents that may target stromal regulation of hormone metabolism or stromal-modulated epithelial cell growth and differentiation. Further studies are required to determine the safety of DHEA use as an over-the-counter supplement and to elucidate the mechanism(s) of DHEA effects in the prostate, including its metabolism to androgenic and/or estrogenic steroids, paracrine induction of secondary factors and its role in prostate growth and gene regulation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Charles Sawyers (UCLA) for providing the LAPC-4 cells, Dr. John Isaacs (Johns Hopkins School of Medicine) for providing the primary prostate stromal cells (5S, 6S, 9S, 12S) and Dr. Vernon Steele (NIH-NCI) and Dr. Angela Brodie, (University of Maryland) for their constructive comments upon reviewing this manuscript. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Abbreviations

- 6S

primary reactive stromal cell

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AR

androgen receptor

- CC

coculture

- CDS

charcoal dextran-treated serum

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- DHEAS

dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Media

- E2

17β estradiol

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ER

estrogen receptor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HSD

hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor

- IGFBP

IGF binding protein

- MC

Monoculture

- PrSC

primary normal prostate stromal cell

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- RPLPO

Ribosomal phosphoprotein PO

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SEM

standard error

- T

testosterone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Belanger A, Candas B, Dupont A, Cusan L, Diamond P, Gomez JL, Labrie F. Changes in serum concentrations of conjugated and unconjugated steroids in 40-to 80-year-old men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1086–1090. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.4.7962278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alesci S, Manoli I, Blackman MR. Dehydrodepiandrosterone (DHEA) In: Coates P, Blackman MR, Cragg G, Levine M, Moss J, White J, editors. Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. 1st ed. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2005. pp. 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein H, Bressel M, Kastendieck H, Voigt KD. Androgens, adrenal androgen precursors, and their metabolism in untreated primary tumors and lymph node metastases of human prostatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 1988;11 Suppl 2:S30–S36. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198801102-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voigt KD, Bartsch W. Intratissular androgens in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic cancer. J Steroid Biochem. 1986;25:749–757. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labrie F, Belanger A, Luu-The V, Labrie C, Simard J, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Candas B. DHEA and the intracrine formation of androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: its role during aging. Steroids. 1998;63:322–328. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha GR, Cooke PS, Kurita T. Role of stromal-epithelial interactions in hormonal responses. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:417–434. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold JT, Le H, McFann KK, Blackman MR. Comparative effects of DHEA vs. testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and estradiol on proliferation and gene expression in human LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E573–E584. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00454.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le H, Arnold JT, McFann KK, Blackman MR. Dihydrotestosterone and Testosterone, but not DHEA or Estradiol, Differentially Modulate IGF-I, IGFBP - 2 and IGFBP-3 Gene and Protein Expression in Primary Cultures of Human Prostatic Stromal Cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00451.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao KV, Johnson WD, Bosland MC, Lubet RA, Steele VE, Kelloff GJ, McCormick DL. Chemoprevention of rat prostate carcinogenesis by early and delayed administration of dehydroepiandrosterone. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3084–3089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein KA, Reiter RE, Redula J, Moradi H, Zhu XL, Brothman AR, Lamb DJ, Marcelli M, Belldegrun A, Witte ON, Sawyers CL. Progression of metastatic human prostate cancer to androgen independence in immunodeficient SCID mice. Nat Med. 1997;3:402–408. doi: 10.1038/nm0497-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weeraratna A, Arnold J, George D, DeMarzo A, Isaacs J. Rational basis for Trk inhibition therapy for prostate cancer. The Prostate. 2000;45:140–148. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20001001)45:2<140::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belanger B, Belanger A, Labrie F, Dupont A, Cusan L, Monfette G. Comparison of residual C-19 steroids in plasma and prostatic tissue of human, rat and guinea pig after castration: Unique importance of extratesticular androgens in men. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 1989;32:695–698. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acacio BD, Stanczyk FZ, Mullin P, Saadat P, Jafarian N, Sokol RZ. Pharmacokinetics of dehydroepiandrosterone and its metabolites after long-term daily oral administration to healthy young men. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orentreich N, Brind JL, Vogelman JH, Andres R, Baldwin H. Long-term longitudinal measurements of plasma dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:1002–1004. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.4.1400863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labrie F, Belanger A, Cusan L, Candas B. Physiological changes in dehydroepiandrosterone are not reflected by serum levels of active androgens and estrogens but of their metabolites: intracrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2403–2409. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.8.4161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valenti G, Denti L, Sacco M, Ceresini G, Bossoni S, Giustina A, Maugeri D, Vigna GB, Fellin R, Paolisso G, Barbagallo M, Maggio M, Strollo F, Bollanti L, Romanelli F, Latini M. Consensus Document on substitution therapy with DHEA in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18:277–300. doi: 10.1007/BF03324662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labrie F, Luu-The V, Labrie C, Simard J. DHEA and its transformation into androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: intracrinology. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22:185–212. doi: 10.1006/frne.2001.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen F, Knecht K, Birzin E, Fisher J, Wilkinson H, Mojena M, Moreno CT, Schmidt A, Harada S, Freedman LP, Reszka AA. Direct agonist/antagonist functions of dehydroepiandrosterone. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4568–4576. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan J, Sharief Y, Hamil KG, Gregory CW, Zang DY, Sar M, Gumerlock PH, deVere White RW, Pretlow TG, Harris SE, Wilson EM, Mohler JL, French FS. Dehydroepiandrosterone activates mutant androgen receptors expressed in the androgen-dependent human prostate cancer xenograft CWR22 and LNCaP cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:450–459. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.4.9906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold JT, Liu X, Allen JD, Le H, McFann KK, Blackman MR. Androgen receptor or estrogen receptor-beta blockade alters DHEA-, DHT-, and E2-induced proliferation and PSA production in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2007;67:1152–1162. doi: 10.1002/pros.20585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold JT, Blackman MR. Does DHEA exert direct effects on androgen and estrogen receptors, and does it promote or prevent prostate cancer? Endocrinology. 2005;146:4565–4567. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin C, Ross M, Chapman KE, Andrew R, Bollina P, Seckl JR, Habib FK. CYP7B generates a selective estrogen receptor beta agonist in human prostate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2928–2935. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Formoso G, Chen H, Kim JA, Montagnani M, Consoli A, Quon MJ. Dehydroepiandrosterone mimics acute actions of insulin to stimulate production of both nitric oxide and endothelin 1 via distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- and mitogenactivated protein kinase-dependent pathways in vascular endothelium. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md.) 2006;20:1153–1163. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen RK, Bissell MJ. Tissue architecture and breast cancer: The role of extracellular matrix and steroid hormones. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2000;7:95–113. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold JT, Kaufman DG, Seppala M, Lessey BA. Endometrial stromal cells regulate epithelial cell growth in vitro: a new co-culture model. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:836–845. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denmeade SR, Sokoll LJ, Dalrymple S, Rosen DM, Gady AM, Bruzek D, Ricklis RM, Isaacs JT. Dissociation between androgen responsiveness for malignant growth vs. expression of prostate specific differentiation markers PSA, hK2, and PSMA in human prostate cancer models. Prostate. 2003;54:249–257. doi: 10.1002/pros.10199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabalin JN, Peehl DM, Stamey TA. Clonal growth of human prostatic epithelial cells is stimulated by fibroblasts. Prostate. 1989;14:251–263. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990140306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong YC, Wang YZ. Growth factors and epithelial-stromal interactions in prostate cancer development. International Review of Cytology. 2000;199:65–116. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)99002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan G, Fukabori Y, Nikolaropoulos S, Wang F, McKeehan WL. Heparinbinding keratinocyte growth factor is a candidate stromal-to-epithelial-cell andromedin. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:2123–2128. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.12.1491693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camps JL, Chang SM, Hsu TC, Freeman MR, Hong SJ, Zhau HE, Von Eschenbach AC, Chung LWK. Fibroblast-mediated acceleration of human epithelial tumor growth in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:75–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell PJ, Bennett S, Stricker P. Growth factor involvement in progression of prostate cancer. Clinical Chemistry. 1998;44:705–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olumi AF, Grossfeld GD, Hayward SW, Carroll PR, Tisty TD, Cunha GR. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Research. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuxhorn JA, McAlhany SJ, Dang TD, Ayala GE, Rowley DR. Stromal cells promote angiogenesis and growth of human prostate tumors in a differential reactive stroma (DRS) xenograft model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3298–3307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu X, Allen JD, Arnold JT, Blackman MR. Lycopene inhibits IGF-I signal transduction and growth in normal prostate epithelial cells by decreasing DHT-modulated IGF-I production in cocultured reactive stromal cells. Carcinogenesis. 2008 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bayne CW, Donnelly F, Chapman K, Bollina P, Buck C, Habib F. A novel coculture model for benign prostatic hyperplasia expressing both isoforms of 5 alpha-reductase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:206–213. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.1.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castellon E, Venegas K, Saenz L, Contreras H, Huidobro C. Secretion of prostatic specific antigen, proliferative activity and androgen response in epithelialstromal co-cultures from human prostate carcinoma. Int J Androl. 2005;28:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goossens K, Esquenet M, Swinnen JV, Manin M, Rombauts W, Verhoeven G. Androgens decrease and retinoids increase the expression of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in LNcaP prostatic adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;155:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lang SH, Stark M, Collins A, Paul AB, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Experimental prostate epithelial morphogenesis in response to stroma and threedimensional matrigel culture. Cell Growth Differ. 2001;12:631–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Marzo AM, Marchi VL, Epstein JI, Nelson WG. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1985–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65517-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regelson W, Loria R, Kalimi M. Hormonal intervention: "buffer hormones" or "state dependency". The role of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), thyroid hormone, estrogen and hypophysectomy in aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;521:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb35284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]