Abstract

Protein phosphorylation has become a focus of many proteomic studies due to the central role that it plays in biology. We combine peptide-based gel-free isoelectric focusing and immobilized metal affinity chromatography to enhance the detection of phosphorylation events within complex protein samples using LC-MS. This method is then used to carry out a quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathway using HeLa cells metabolically labeled with 15N-containing amino acids, where 145 phosphorylation sites were found to be up-regulated upon the activation of the TNF pathway.

Keywords: Isoelectric focusing, IMAC, phosphoproteome, metabolic labeling, TNF, PKA, apoptosis

Introduction

Protein phosphorylation has been shown to be an important post-translational modification, regulating activities as diverse as protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity, subcellular localization, and ubiquitin-mediated degradation1. Due to the wide spectrum of changes that phosphorylation can impart to a protein, it is no surprise that this post-translational modification has been implicated in numerous biological processes. On a larger scale, changes in the phosphorylation of specific proteins have been implicated in a variety of human diseases; and because of this, there is an enormous amount of interest in the development of methods to identify protein phosphorylation on a global scale in the hope of unveiling phosphorylation events that are specific to a disease state. Identifying such events will be critical in understanding many different diseases and pivotal in determining therapeutic targets for future drug development.

Identifying protein phosphorylation, however, has proven to be a formidable challenge. In the past, a variety of techniques, primarily involving biochemical and molecular biology tools, have been used to analyze protein phosphorylation. In typical studies, these methods can only practically be applied to a few proteins at a time; resulting in a slow progress in identifying new phosphorylation sites. However, the use of mass spectrometry in the analysis of protein phosphorylation has dramatically sped up the process; and because of this, a variety of mass spectrometry platforms are currently being used to study phosphorylation. Within the past few years, tandem mass spectrometers have dominated these analyses because collected tandem mass spectra can be used to not only identify phosphorylated peptides and assign them to a specific protein, but, in many cases, also localize the site of phosphorylation to a particular amino acid2–6.

It has been estimated that as many as 30% of mammalian proteins are phosphorylated. Even though a large percentage of proteins may be phosphorylated in mammalian cells, a large dynamic range in protein concentration results in some phosphoproteins being present at concentrations orders of magnitude lower than others. This issue is the biggest obstacle faced in attempts to carry out a complete phosphoproteomic analysis by mass spectrometry. Additionally, phosphorylation of a particular site in vivo is often substoichiometric7 making the aforementioned problem even more difficult. Due to this, it is generally agreed upon that some type of enrichment scheme which can target phosphoproteins and/or phosphopeptides (reducing the complexity of the sample to be analyzed by mass spectrometry) is needed in order for a complete phosphoproteomic analysis of a complex protein mixture to be carried out.

If tandem mass spectrometry is to be used for an analysis, another challenge lies in the inherent difficulty in identifying phosphopeptides compared to unmodified peptides. This difficulty is due to multiple factors including: 1.) the highly negative charge of a phosphopeptide results in suppression of ionization when using the positive ion mode of detection8 (which is typically used in MS/MS analysis of peptides), and 2.) MS/MS spectra from phosphoserine and phosphothreonine-containing peptides are often of poor quality due to the dominant loss of phosphoric acid and reduced amount of informative cleavage across the peptide backbone9. As a result, some laboratories have developed and/or utilized mass spectrometry-specific methods to address these issues in phosphopeptide analysis2, 5–7, 10.

A number of phosphoprotein/phosphopeptide enrichment strategies coupled to mass spectrometry have been developed over the last few years, most of which have been previously reviewed3, 8, 11, 12. However, no method has matured and become robust enough to be considered the method of choice. Thus, at this point, phosphoproteomic method development is still needed. In this study, we analyze the effects of fractionating a digested mammalian whole cell extract via isoelectric focusing (IEF) prior to LC-MS analysis. We demonstrate that this pI-based fractionation allows for a moderate enrichment of phosphopeptides in the low pH fractions. We then combine this fractionation procedure with immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) to generate a highly enriched pool of phosphopeptides that is subsequently analyzed by an LC-MS/MS/MS strategy previously shown to enhance the detection of phosphoserine and phosphothreonine-containing peptides5, 6. This combined approach is used to quantitatively analyze phosphorylation events specific to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signal transduction pathway using HeLa cells metabolically labeled with 15N-containing amino acids. This pathway was chosen for two reasons: first, because phosphorylation is known to play a key role in the transduction of the TNF signal through multiple protein components; and second, because the pathway is of great interest to many researchers due to its integral role in inflammation, apoptosis, and cancer13–15. From a combined quantitative and qualitative analysis, ~700 phosphopeptides were identified, where 106 phosphopeptides and 145 phosphorylation sites were found to be up-regulated by TNF; these consisted of sites previously known to be regulated by TNF, known sites with unknown modes of regulation, and entirely novel phosphorylation sites.

Experimental Section

Procedures. 1. Cell Culture and Protein Extraction

HeLa-S3 cells purchased from National Cell Culture Center were used in the initial IEF experiments. Whole cell protein extract was prepared with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as directed by the manufacturer. For the analysis of untreated and TNF-treated cells, adherent HeLa cells were grown in “Homemade” DMEM media and is fully detailed in Supplementary Methods, and is similar to the published recipe for 10-013 DMEM from Mediatech, Inc. Briefly, culture media was made using dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, 26400) to 10%, and either 14N or 15N amino acid mix (Spectra Stable Isotopes, 520000/532098) to 800 mg/L. The percent isotope enrichment for the 15N-labeled amino acid mix was <98%. For each culture, the adherent cells (grown in either four or five 15 cm plates) were washed with PBS and either left untreated or were treated with recombinant human tumor necrosis factor alpha (R&D Systems, 210-TA) at 20ng/ml in PBS for seven minutes as previously recommended16. Supernatant was then cleared and the cells were detached via Trypsin/EDTA solution (Cellgro, 25-053-C1) and scraping. The cell suspension was then spun at 2,200 rcf for two minutes, and the supernatant was decanted. Protein was then extracted from the cell pellet via Trizol reagent.

2. Isoelectric Focusing of Protein Digest

Precipitated protein from a Trizol extraction was resuspended in 8M urea 100mM Tris pH 8.5 at ~4.5mg/ml (expected amount of protein was determined from previous experiments where ~0.12mg of protein was extracted from 1×106 HeLa cells using Trizol reagent) and incubated at 50°C for 30 min. with intermittent vortexing in order to get the majority of the precipitate into solution. The protein mixture was then reduced by adding TCEP to 5mM and incubating for 30 min. at room temperature (R.T.), followed by cysteine alkylation with iodoacetamide at 10mM and incubating in the dark for 30 min. at R.T. The mixture was then diluted to 4M urea by adding an equivalent volume of 100mM Tris pH 8.5, and CaCl2 was added to 2mM. Trypsin (Promega, modified sequencing grade) was added at ~1:500 (enzyme:substrate, wt/wt) and incubated at 37°C for ~24 hr., then trypsin was added again at ~1:500 and incubated for another 24 hr at 37°C. Approximate, but relative, protein concentration of each sample was determined after digestion using both the DC Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) and A280 readings. Each digest was then desalted by solid phase extraction on C18 (SPEC, Varian) according to manufacturers instruction and lyophilized by speed vac (Savant). The sample was then prepared for gel-free isoelectric focusing using the ZOOM® IEF Fractionator (Invitrogen). Buffers and reagents were prepared as described in Supporting Information. 2.5 mg of the desalted digest was resuspended in 4.188ml of 1× ZOOM Fractionator sample buffer without CHAPS. A total of 2 mg was loaded in the fractionator and run as described in Supporting Information, using ZOOM® Disks of pH 3.0, 4.6, 5.4, 6.2, 7.0, and 10.0. After running, each of the five fractions was named after the pH of the lower of the two disks flanking the fraction, and stored at −80°C. Prior to analysis by MudPIT, one fourth of each fraction was spun at ~14,000 rcf for 10 min to remove insoluble material. Formic acid was then added to the supernatant to a final concentration of 4% (v/v) prior to column loading.

3. Isoelectric Focusing of Intact Protein

Precipitated protein from a Trizol extraction was resuspended in 1x ZOOM Fractionator sample buffer (containing CHAPS) to an estimated concentration of 4mg/ml, and heated to 50°C for 20 min., with intermittent vortexing. Protein was reduced with DTT and cysteines were alkylated with DMA (N,N-dimethylacrylamide, 99%, Sigma) as described in Supporting Information, and 2 mg was then run on the fractionator as above. One fourth of each fraction was separately subjected to acetone precipitation in order to remove CHAPS. The precipitated protein was resuspended in 100 µl of 8 M urea 100 mM Tris pH 8.5 and heated to 50°C for 30 min. with intermittent vortexing. The concentration of urea was reduced to 4 M by the addition of an equal volume of 100 mM Tris pH 8.5, CaCl2 was added and the protein mixture was subjected to tryptic digestion as above. The digestions were stopped with the addition of formic acid to 4%.

4. MudPIT Analysis

One fourth of each processed fraction was separately loaded onto a 3-phase MudPIT column17 described in detail in Supplementary Methods. Subsequently, LC/LC-MS/MS was carried out (see Supplementary Methods) using an HP1100 HPLC (Hewlett Packard) online with an LCQ Deca ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron), and MS/MS spectra were collected as previously described18. MS/MS spectra were processed and searched against a human protein database differentially considering phosphorylation at serine and threonine using SEQUEST19 (further details in Supplementary Methods). All subsequent filtering and comparisons of identifications were made using DTASelect and Contrast software20. A description of the algorithm used to determine the pI of peptides can be found at the following link, http://fields.scripps.edu/DTASelect/20010710-pI-Algorithm.pdf.

5. Phosphopeptide enrichment and analysis of +/− TNF-treated cells

Protein was extracted from each 14N or 15N-labeled culture and digested with trypsin as described above. Protein/peptide concentrations, after digestion, were initially determined by A280 readings. After determining the accurate relative concentrations of each digest (as described in Supplementary Methods), a 1:1 digest mixture (3.8 mg total) was made, subsequently desalted over C18, split into two aliquots and fractionated by two separate gel-free isoelectric focusing runs as described above. The “pH 3” fractions from each run were combined, as were the two “pH 4.6” fractions. To remove insoluble material, each fraction (~1150 µl) was filtered using 0.45 µm Ultrafree-MC 0.5 ml centrifugal filter devices (Millipore) and then split into eight aliquots. Each aliquot was subjected to IMAC using 25µl Gallium-Chelated resin in a mini-spin column as described by the manufacturer (Pierce, 89853) and further detailed in Supporting Information. All IMAC eluates were combined and split into three aliquots for analysis by LC-MS. Each aliquot was loaded onto 4 cm of 5µm-sized C18 resin (Aqua, Phenomenex) packed in 100 µm (i.d.) fused silica attached to a filter assembly, and then washed with buffer A for 5 min. An 11 cm C18 analytical column (100 µm (i.d.) with a tip laser-pulled to 5–15 µm) was then attached to the assembly and run on an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron) attached to an HP 1100 HPLC and developed using a reversed-phase gradient (see Supplementary Methods). The instrument method consisted of a full MS scan from 400–1400 m/z followed by data-dependent MS/MS on the five most intense ions. Additionally, MS/MS/MS (MS3) was triggered for precursor ions undergoing a neutral-loss of either 98, 49, or 32.7 m/z upon MS/MS5, 6. AGC targets of 20,000 and 10,000 with 50 and 100 msec max ion times were used for MS and MSn scans, respectively. The minimum signals required for MS/MS and MS3 were 1000 and 100, respectively; and an isolation width of 3 m/z and normalized collision energy of 35% was used for both. RAW files were split into MS2 and MS3 files using the program Raw Extract (written by John Venable). MS2 files were filtered using the previously described program21, and MS3 files were left unfiltered. The MS2 and MS3 files were then separately subjected to SEQUEST searches. To construct the database used in these searches, the EBI-IPI human database (version 3.04 released 03-07-2005) was first attached to a list of frequently occurring contaminants (e.g. proteases and keratins), then this database was combined with its reversed version. The parameters of the searches were similar to those used above; however, for MS2 searches, tyrosine phosphorylation was now considered, and, additionally for MS3 searches, a loss of 18 Da was differentially searched for on serine and threonine, which is indicative of a neutral loss of phosphoric acid from a phosphoserine or phosphothreonine-containing peptide. Two separate searches for each MS data file were carried out, considering both 14N and 15N-containing amino acids. In filtering the search results, a new feature was added to DTASelect that reports the DeltaCN of the first unrelated peptide in amino acid sequence, essentially ignoring peptides identical in sequence but modified at a different site when filtering based on the DeltaCN of each identification. This is done to allow for the identification of phosphopeptides where the exact location of the phosphorylation site(s) can not be conclusively determined by SEQUEST. This is a fairly common problem encountered in phosphopeptide analysis, and is due to instances where phosphopeptides containing closely-spaced serines and or threonines produce MS/MS spectra that are missing definitive fragment ions. The SEQUEST identifications were then filtered as described above with the additional removal of identifications from the reverse database. Ultimately, phosphopeptides with DeltaCN scores above 0.08 were determined to have the site(s) of phosphorylation localized, whereas those with scores below 0.08 are labeled as not-localized and all of the probable sites are listed (using the 2nd-5th best scoring peptides within a DeltaCN score of 0.08). RelEx was then used to quantify relative abundances of the 14N and 15N versions of the identified phosphopeptides essentially as previously reported 22, except that a precursor ion signal to noise filter of 2 was used, the correlation filter was dropped, and the atomic percent enrichment for the 15N-containing samples were ~90% (see Supplementary Methods).

Results and Discussion

Phosphopeptide Enrichment from Digests of Whole Cell Protein using gel-free IEF

Upon phosphorylation, peptides will generally shift from a higher to a lower pI due to the highly negative charge of the added phosphate moiety. Due to this property, we were able to generate fractions that are enriched in phosphopeptides by subjecting an extremely complex peptide mixture to gel-free IEF using the ZOOM IEF Fractionator (Invitrogen), which is modeled after a previously described device23. To generate the sample, a whole cell protein extract was prepared from HeLa cells using Trizol reagent, digested with trypsin, and subsequently desalted by solid phase extraction on C18. Approximately 2 mg of the peptide mixture was then subjected to gel-free IEF, generating five fractions based on pI (see Experimental Section). One quarter of each fraction was then subjected to an LC/LC-MS/MS analysis termed MudPIT (multidimensional protein identification technology) (see Experimental Section). MS/MS spectra from this analysis were ultimately searched against a human database using the algorithm SEQUEST19, differentially considering serine and threonine to be phosphorylated.

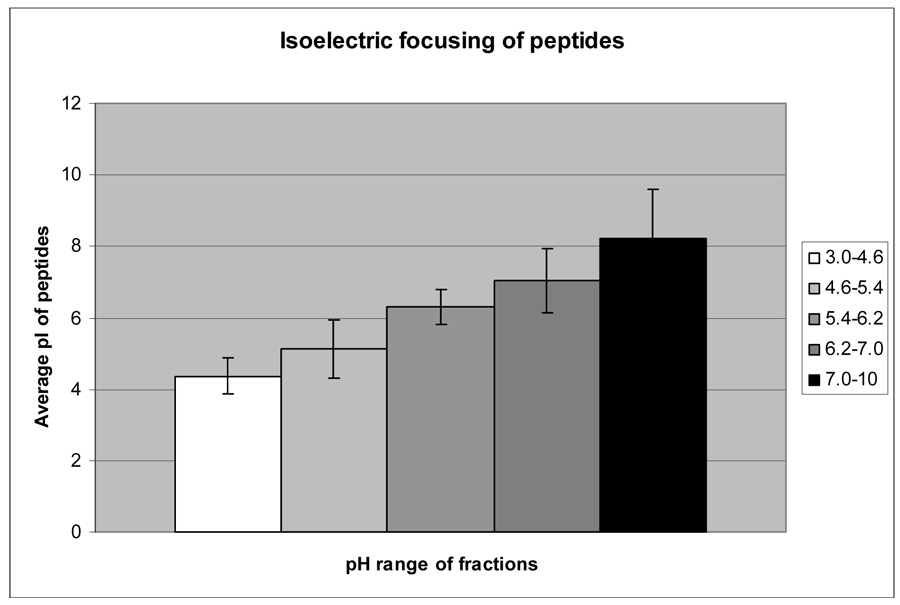

To determine the effectiveness of the IEF fractionation, we first generated lists of the peptides identified in each IEF fraction by MudPIT. To do this, we used default cross correlation (XCorr) (1.8, 2.5 and 3.5, for +1, +2, and +3 charged peptides, respectively) and ΔCn (0.08) cutoff values, and allowed only for the identification of fully tryptic unmodified peptides. Together, 5,242 unmodified peptides were identified (this is the non-redundant number, some peptides were identified in multiple pH fractions), corresponding to 1,934 proteins. In Figure 1 we show the average pI of the unmodified peptides that were identified in each IEF fraction; the pI of each peptide was determined as previously described (Experimental Section). These results demonstrate that a pI-based fractionation of peptides was effectively achieved. When considering the identification of phosphopeptides, the same filtering criteria as described above were used. Table 1 shows both the number of phosphopeptides and unmodified peptides identified in each fraction. We then compared the ratio of the number of phosphopeptides to the number of unmodified peptides found in each fraction. Displayed in Table 1 is the ratio for each IEF fraction, normalized to fraction “pH 3” (fractions are named after the lower of the two pH discs which flank each IEF fraction/chamber). It is apparent that this ratio generally decreases from fraction “pH 3” to fraction “pH 7”, suggesting that there is an enrichment of phosphopeptides occurring in the lower pI fractions. Additionally, this experiment was repeated two times producing similar results as those described above (data not shown). Lastly, the pI of the identified phosphopeptides were determined using the web-based program ProMoST24. Similar to the analysis of unmodified peptides, the pI of the phosphopeptides also correlate with the pH fraction that they were identified in (data not shown).

Figure 1. Isoelectric focusing of trypsin-digested whole cell protein extract.

HeLa cell protein extract was digested with trypsin and subjected to prefractionation via IEF prior to MudPIT analysis. For the unmodified peptides identified (see text for criteria), the pI of each was determined and the average for each IEF fraction is displayed.

Table 1.

IEF of digested whole cell protein extract, comparisons of unmodified (unmod.) and phosphorylated (phos.) peptides identified in each fraction by MudPIT.

| IEF fractions | unmod. peptides | phos. peptides | phos./unmod.* |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH 3 | 555 | 12 | 1.00 |

| pH 4.6 | 592 | 13 | 1.02 |

| pH 5.4 | 1867 | 13 | 0.32 |

| pH 6.2 | 1445 | 0 | 0.00 |

| pH 7 | 1350 | 5 | 0.17 |

| Non-redundant Total | 5242 | 41 | |

Ratio of the number of identified peptides normalized to fraction pH 3.

IEF of Intact Protein

We were also interested in pre-fractionating intact proteins via IEF and determining how this would compare to the above method in regards to identifying phosphorylation sites. To do this, whole cell extract was prepared as above, using Trizol reagent, and the protein precipitate was then resolubilized and subjected to IEF fractionation as described in the Experimental Section. One fourth of each IEF fraction was precipitated by acetone, in order to remove detergent, digested with trypsin, and then subjected to the same MudPIT analysis as above. Table 2 shows the number of proteins, unmodified peptides and phosphopeptides identified in each IEF fraction. From this analysis it can be seen that there is no particular enrichment of identified phosphopeptides in any of the fractions. This shows that phosphoproteins within a complex protein mixture can not be enriched by IEF, as opposed to what was seen for phosphopeptides within a complex peptide mixture. This is not surprising, since it is expected that phosphorylation will generally have more of an effect in reducing the pI of a typical tryptic peptide than of a full length protein due to the large difference in amino acid sequence length between the two.

Table 2.

IEF of whole cell protein extract, comparisons of unmodified and phosphorylated peptides and corresponding proteins identified in each fraction by MudPIT.

| IEF fractions | proteins | unmod. peptides | phos. peptides |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH 3 | 388 | 801 | 3 |

| pH 4.6 | 327 | 811 | 1 |

| pH 5.4 | 403 | 1241 | 7 |

| pH 6.2 | 566 | 1723 | 5 |

| pH 7 | 516 | 1085 | 8 |

| Non-redundant Total | 1714 | 5435 | 23 |

Quantitative Phosphoproteomic Analysis of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Pathway

Due to the inability of peptide-based IEF to produce a satisfactory pool of phosphopeptides, we decided to try using IMAC downstream of this separation procedure in order to enhance the enrichment of phosphopeptides from a complex protein digest. To do this, different amounts of each IEF fraction was subjected to IMAC and subsequently analyzed by LC-MS. Based on the number of phosphopeptides and unmodified peptides identified in trial runs (data not shown), it was decided that only the two lowest pI fractions (“pH 3” and “pH 4.6”) would be subjected to IMAC in future analyses. These two fractions produced the highest number of identified phosphopeptides in the IMAC eluates and also the best ratios of phosphopeptides to unmodified peptides (data not shown).

To demonstrate the effectiveness of combining peptide-based IEF and IMAC, we carried out a quantitative analysis of the phosphorylation events that are induced by the activation of the TNF receptor in HeLa cells. Adherent HeLa cells were grown in media with either 14N or 15N-labeled amino acids, where the 14N culture was stimulated with TNF-α for ~7 minutes and the other left untreated. Subsequently, a whole cell protein extract was prepared and digested with trypsin as previously described. A 1:1 mixture of each digest was made (see Experimental Section) and then fractionated by IEF as previously described. The two lowest pI fractions were then separately subjected to IMAC, subsequently pooled, and then analyzed by LC-MS/MS/MS using a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ, Thermo Electron) in triplicate; where, in addition to data-dependent MS/MS, a data-dependent MS/MS/MS scan was carried out upon the observation of a neutral loss of phosphoric acid from the precursor ion in the MS/MS spectra. This neutral loss is common during CID of phosphoserine and phosphothreonine-containing peptides, due to the labile nature of the phosphate bond; where the neutral loss ion often dominates the MS/MS spectra, resulting in poor quality and difficult to identify spectra9. Essentially, the aforementioned MS/MS/MS strategy is designed to increase the number of phosphoserine and phosphothreonine containing peptides identified, and has previously been shown to be a successful strategy5, 6. Resulting spectra were searched against a combined forward and reversed human protein database (IPI) using SEQUEST; MS/MS and MS/MS/MS were separately searched as describe in the Experimental Section resulting in the identification of phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine-containing peptides from both the 14N and 15N sample. In total 701 phosphopeptides were identified between the three replicates.

The software program RelEx22 was then used to quantify the relative amounts of the 14N and 15N-containing phosphopeptides identified in the above analysis. Utilizing identifications from both MS/MS and MS/MS/MS spectra, RelEx was used to automatically determine the relative abundance ratio of the precursor ion peaks for the corresponding 15N and 14N-containing phosphopeptides. Due to stringent filtering22, a large number of identifications could not be automatically quantified by RelEx and were thus discarded in the quantitative analysis. Ultimately, 223 phosphopeptides passed the quantitative filtering criteria. Of these, 33 phosphopeptides (containing 56 phosphorylation sites) were found to be up-regulated by 2-fold or more and 15 phosphopeptides (containing 23 sites) were found to be down-regulated by 2-fold or more due to treatment with TNF-α. In previous studies, 2-fold changes have been shown to be biologically significant6. Within the up-regulated group, some of the phosphorylation sites have been previously found to be induced upon activation of the TNF receptor (see below) or due to the activation of a known component of the TNF signaling pathway (see below), indicating that the combined method is capable of finding and quantifying differences in phosphorylation events induced upon the activation of a signal transduction cascade in mammalian cells.

The reciprocal labeling experiment was also carried out, where the above experiment was essentially repeated except that the cells grown in 14N-containing media were left untreated and those grown in 15N-containing media were stimulated with TNF-α. This type of reciprocal labeling experiment was performed in an attempt to confirm the first set of quantitative measurements by observing the reciprocal measurements when the labeling of the samples is reversed. Such confirmation also helps eliminate the possibility of a biological isotope effect. In relation to this experiment, it would eliminate the possibility that the observed quantitative differences between the samples were due to biological changes induced by differences in the nitrogen content of the medias, adding confidence to the notion that all differences observed are the result of the activation of the TNF pathway. When comparing the two reciprocal labeling experiments, it was found that many of the same phosphopeptides were quantified in both experiments (Supporting Information); however, none of the up or down regulated phosphopeptides were quantified in the reciprocal labeling experiment. A number of reasons could explain these results, some of which could include: 1.) a reduction in the ability to identify incomplete 15N-labeled peptides via SEQUEST; 2.) variation in sample processing; or 3.) experimental biological variation. A complete listing of results from the quantitative analyses can be found in Supporting Information.

As previously mentioned, a large number of identified phosphopeptides could not be used in the above quantitative analysis of the TNF pathway. The explanation lies in the fact that tandem MS can be acquired from precursor ion signals with low signal-tonoise, where an identification can be made eventhough the precursor ion peak can not be quantified. However, we felt that biologically useful information could still be extracted from this identification data. We thus decided to carry out a qualitative comparison of the phosphopeptides identified in the above experiments in an attempt to uncover additional phosphorylation events that are specific to the TNF pathway. To do this, we compared the phosphopeptides identified in the 14N-TNF-treated sample to the combined identifications of the 14N-untreated and the 15N-untreated samples. From this comparison, a list was made consisting of phosphopeptides that were found in at least two replicates from the 14N-TNF-treated sample and not found in any of the replicates from the untreated samples. Additionally, phosphopeptides with the same sequence but differing in the site of phosphorylation were considered the same peptide, preventing such phosphopeptides from making it on this list. Ultimately, 79 phosphopeptides containing a total of 97 phosphorylation sites met the above criteria and will subsequently be deemed TNF-regulated (Supporting Information).

The phosphorylation sites determined to be differentially regulated in both the quantitative and qualitative analysis were further scrutinized with the aid of two public databases: PhosphoSite™ (http://www.phosphosite.org) and Swiss-Prot (http://us.expasy.org/sprot). We will only focus on the phosphorylation events found to be upregulated by TNF treatment for the remainder of the discussion. Although the sites that were found to be phosphorylated only in the untreated cells will not be discussed, these may represent sites of dephosphorylation that are specific to the TNF pathway, and thus are also worthy of further analysis.

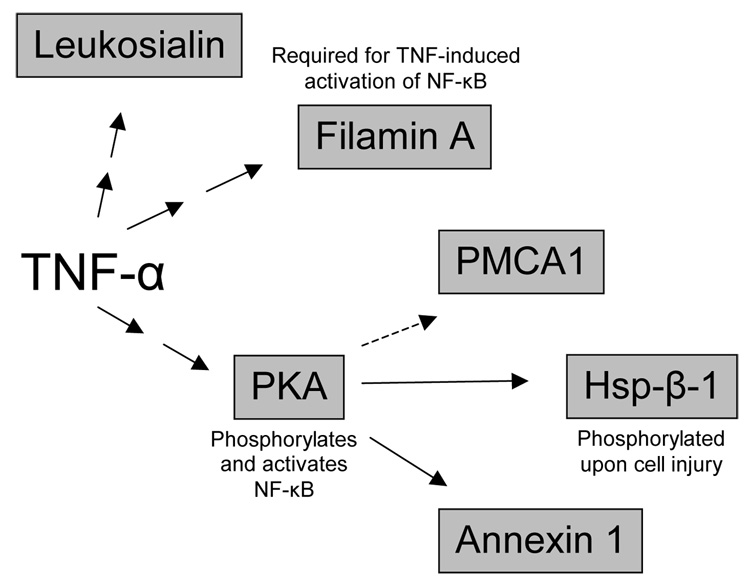

Within the aforementioned lists of TNF-regulated phosphorylation events, the majority of the sites identified are novel. Of those previously identified, a significant majority have only been identified in a biologically ‘non-specific’ phosphoproteomic study5; and thus the mode of regulation, if any, is unknown. However, some of the phosphorylation sites identified here have been previously shown to be regulated by kinases that are activated during the stimulation of the TNF pathway, and the corresponding proteins are illustrated in Fig. 2; additionally, these sites of phosphorylation along with additional quantitative and qualitative data on the identified phosphopeptides are listed in Table 3. Interestingly, a phosphorylation site was found on PKA catalytic subunit α (PKA-c-α) that has previously been shown to activate its kinase activity25. Related to the activation of PKA, a number of known PKA-dependent phosphorylation sites were found to be upregulated upon TNF-α treatment; this includes Hsp-β-126, annexin 127, and possibly PMCA1 (a site was found 20 a.a. away from a known site28), which is illustrated in Fig. 2. Most importantly, PKA has been shown to be activated during highly related signaling events initiated by the ligands IL-1 and LPS that lead to the direct phosphorylation of NF-κB by PKA29. Since IL-1 and LPS mediated activation of NF-κB share many of the same signaling components that are utilized in the TNF-α cascade30, it is not surprising to uncover these PKA-specific phosphorylation events as being regulated by TNF-α in this study. Also, there were additional TNF-regulated phosphorylation sites found on leukosialin and filamin A, both of which have been shown to be phosphorylated by other kinases known to be activated by TNF-α31, 32. Some of these proteins (i.e. PKA, filamin A, and Hsp-β-1) are also known to have certain properties or functions related to the TNF pathway, and these functions are further detailed in Fig. 2. However, in only one of these three proteins is it known what the functional consequence is of the identified phosphorylation event; in this case, for PKA, the consequence is in the activation of its kinase-activity resulting in the phosphorylation and activation of NF-κB29 including other factors in the pathway. However, the effect of the phosphorylations on Hsp-β-1 and filamin A are not known. Altogether, the aforementioned phosphorylation events depicted in Fig. 2 demonstrate that many of the TNF-regulated sites identified in this study are bona fide TNF-regulated events, indicating that the analysis as a whole was successful in its aim and, thus, should lend confidence to the other phosphorylation sites that are also determined to be TNF-regulated in our study.

Figure 2. Up-regulated phosphorylation events found that have been previously linked to the TNF-α pathway.

The proteins boxed in grey were found to be phosphorylated in a TNF-α-dependent manner. Found were a kinase-activating phosphorylation on PKA-c-α and previously known PKA-dependent phosphorylation sites found on annexin 1, Hsp-β-1, and one possible PKA site on PMCA1 (see text). Other findings included sites on leukosialin and filamin A. All phosphorylation events have been directly or indirectly implicated in the TNF-α pathway, and some of the proteins have been implicated in additional activities associated with the action of TNF-α.

Table 3.

TNF-up-regulated sites found that have been previously linked to the pathway.

| IPI # | Fold abundance increase upon TNF-stimulation* | Qualitatively determined to be upregulated** | Site(s)*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukosialin | IPI00027430.1 | 5.9 | S351, S363, S368 | |

| Heat-shock protein beta-1 (Hsp-β-1) | IPI00025512.2 | 2.9 | S15 | |

| 2.5 | S82 | |||

| Annexin 1 | IPI00218918.3 | 6.5 | T216, T223, T226/T227 | |

| Filamin A | IPI00302592.1 | 2 | S2156 | |

| Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase 1 (PMCA1) | IPI00021695.1 | 3 | S1193 | |

| cAMP-dependent protein kinase, alpha-catalytic subunit (PKA-c-α) | IPI00217960.1 | 3 | T190/T188 |

Determined by RelEx

This is the number of times each phosphopeptide was identified in the 3 replicate runs, each is on the qualitatively-determined TNF-regulated list described in the text.

Sites listed were confidently identified, except for those associated with a slash. In those cases all probable sites are listed in order of probability of occurrence (determined by SEQUEST results).

Regarding the other phosphorylation sites that we found to be regulated by TNF-α, we decided to look at the functions of the corresponding proteins in an attempt to gain further insight into this group. Interestingly, a number of proteins were found to be implicated in apoptosis. These proteins, listed in Table 4,,have been found to play a variety of roles in this cellular process33–38. Also, the proteins known function in apoptosis along with information on the corresponding sites and phosphopeptides identified are listed in Table 4. In addition, the majority of these phosphorylation events are novel; except for two: 1.) that of DAP5, which was found in a non-comparative global phosphoproteomic analysis where no mode of regulation was determined5 and 2.) that of PAK2, where it has been shown to correlate with kinase activation39. As previously mentioned, apoptosis can be triggered by TNF-α in some contexts13–15; thus, it is not surprising that proteins associated with this cellular process were found to be phosphorylated upon TNF-α treatment. Due to the association of these proteins with apoptosis, one could speculate that these phosphorylation events may regulate the cells decision to undergo apoptosis upon stimulation of the TNF receptor. However, further experiments will be needed to confirm such associations and should be of great interest to those studying this cellular process.

Table 4.

TNF-up-regulated phosphorylation sites found in proteins previously implicated in apoptosis.

| IPI # | Function in apoptosis | Abundance Increase* | Qual. determined** | Site(s)*** | Novel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 (RIP2) | IPI00021917.1 | Inducer of apoptosis | 5.6 | S174, S180, S181 | Yes | |

| Ankyrin 2 (ANK2) | IPI00007834.1 | Contains death domain | 3.1 | T1806, T1818 | Yes | |

| Caspase recruitment domain protein 6 (CARD6) | IPI00306794.3 | Contains caspase recruitment domain | 3.5 | Y155/S154, T158, S161 | Yes | |

| Death-associated protein 1 (DAP1) | IPI00018117.1 | Positive mediator of apoptosis | 2 | S51/S49 | Yes | |

| Death-associated protein 5 (DAP5) | IPI00015952.1 | Caspase-mediated regulation | 2 | T508/T506 | No | |

| Bcl-2-associated transcription factor 1 (Btf1) | IPI00006079.1 | Inducer of apoptosis | 3 | S385 | Yes | |

| BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa protein-interacting protein 2 (Nip2) | IPI00030399.1 | Anti-apoptotic | 2 | S114 | Yes | |

| P21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2) | IPI00419979.1 | Caspase-mediated activation | 3 | S141/T143 | No |

RelEx-determined fold abundance increase upon TNF-stimulation

This is the number of times each phosphopeptide was identified in the 3 replicate runs, each is on the qualitatively-determined TNF-regulated list described in the text.

Sites listed were confidently identified, except for those associated with a slash. In those cases all probable sites are listed in order of probability of occurrence (determined by SEQUEST results).

Conclusion

In this report we utilize a combination of methods to enhance the detection of phosphorylation sites within a complex protein mixture and apply these methods in a quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of the TNF pathway. IEF is used in this study to enrich for phosphopeptides within a complex protein digest. A related method has recently been published that exploits the charge state of phosphorylated tryptic peptides in a pre-fractionation step using strong cation exchange resin prior to LC-MS/MS analysis, resulting in the identification of primarily singly phosphorylated peptides5, 6. In our study however, the pre-fractionation step via IEF allowed for the collection of multiply phosphorylated tryptic peptides. In the future, it will be of interest to compare the two methods in the ability to efficiently and effectively produce phosphopeptide-enriched fractions from complex protein digests that are representative of the actual phosphopeptide make up of a whole cell protein digest.

Combining a pre-fractionation step prior to IMAC appears to be critical for the overall success in the enrichment of phosphopeptides from a complex peptide mixture, a process of which is fraught with problems of “non-specific” binding of certain classes of unmodified peptides40. In addition to our study, similar phosphoproteomic studies have used pre-fractionation prior to IMAC in order to increase the specificity for phosphopeptide enrichment by IMAC6, 41. In one of these studies, high-resolution SCX chromatography was used as the pre-fractionation step prior to IMAC6. Regarding this use of a high-resolution pre-fractionation step, it would be interesting to compare the low-resolution IEF fractionation method used here to those that can achieve a higher resolution, such as ones recently published42, 43, and determine if a higher portion of a whole cell protein digest could be used in the IMAC fractionation step without detrimentally increasing the percentage of co-purifying unmodified peptides.

One obvious weakness in our quantitative analysis was the large discrepancy between the number of phosphopeptides identified and the number that could be quantified. The biggest factor contributing to this is the low signal to noise of many of the phosphopeptides observed in the full mass scan (MS spectra). One way that this could be improved is by the use of a hybrid mass spectrometer where time-expensive signal averaging of precursor ion MS spectra can be carried out in parallel with the acquisition of MS/MS spectra, as has been previously done6. Such a strategy should result in better signal to noise ratios within MS spectra ultimately improving quantitation, and thus we will explore the usefulness of such a strategy in the near future.

Supplementary Material

Complete lists and descriptions of the phosphopeptides identified in this study are included as supplementary data along with supplementary methods.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Kumar Bala of Invitrogen for kindly providing the ZOOM IEF Fractionator, Jeff Johnson for programming help, Christian Ruse for thoughtful recommendations, Emily Chen for careful review of the manuscript, and additional members of the Yates lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants RR11823-09, EY13288, and MH067880. G.T.C. and J.D.V. are supported by NIH National Research Service Award fellowships.

References

- 1.Hunter T. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yates JR, 3rd, Eng JK, McCormack AL, Schieltz D. Anal Chem. 1995;67:1426–1436. doi: 10.1021/ac00104a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann M, Ong SE, Gronborg M, Steen H, Jensen ON, Pandey A. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01944-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ficarro SB, McCleland ML, Stukenberg PT, Burke DJ, Ross MM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, White FM. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:301–305. doi: 10.1038/nbt0302-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villen J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruhler A, Olsen JV, Mohammed S, Mortensen P, Faergeman NJ, Mann M, Jensen ON. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:310–327. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400219-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annan RS, Huddleston MJ, Verma R, Deshaies RJ, Carr SA. Anal Chem. 2001;73:393–404. doi: 10.1021/ac001130t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLachlin DT, Chait BT. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:591–602. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeGnore JP, Qin J. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:1175–1188. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(98)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syka JE, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9528–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters EC, Brock A, Ficarro SB. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2004;4:313–324. doi: 10.2174/1389557043487330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loyet KM, Stults JT, Arnott D. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:235–245. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R400011-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiDonato JA, Hayakawa M, Rothwarf DM, Zandi E, Karin M. Nature. 1997;388:548–554. doi: 10.1038/41493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen G, Goeddel DV. Science. 2002;296:1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercurio F, Murray BW, Shevchenko A, Bennett BL, Young DB, Li JW, Pascual G, Motiwala A, Zhu H, Mann M, Manning AM. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1526–1538. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald WH, Ohi R, Miyamoto DT, Mitchison TJ, Yates JR., 3rd Int J Mass Spec. 2002;219:245–251. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR., 3rd Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR., 3rd J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabb DL, McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd J Proteome Res. 2002;1:21–26. doi: 10.1021/pr015504q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bern M, Goldberg D, McDonald WH, Yates JR., 3rd Bioinformatics. 2004;20 Suppl 1:I49–I54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacCoss MJ, Wu CC, Liu H, Sadygov R, Yates JR., 3rd Anal Chem. 2003;75:6912–6921. doi: 10.1021/ac034790h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuo X, Speicher DW. Anal Biochem. 2000;284:266–278. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halligan BD, Ruotti V, Jin W, Laffoon S, Twigger SN, Dratz EA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W638–W644. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cauthron RD, Carter KB, Liauw S, Steinberg RA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1416–1423. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butt E, Immler D, Meyer HE, Kotlyarov A, Laass K, Gaestel M. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7108–7113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m009234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varticovski L, Chahwala SB, Whitman M, Cantley L, Schindler D, Chow EP, Sinclair LK, Pepinsky RB. Biochemistry. 1988;27:3682–3690. doi: 10.1021/bi00410a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce JI, Yule DI, Shuttleworth TJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48172–48181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhong H, SuYang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. Cell. 1997;89:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piller V, Piller F, Fukuda M. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18824–18831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo MS, Ohta Y, Rabinovitz I, Stossel TP, Blenis J. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3025–3035. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.3025-3035.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deiss LP, Feinstein E, Berissi H, Cohen O, Kimchi A. Genes Dev. 1995;9:15–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kasof GM, Goyal L, White E. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4390–4404. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyd JM, Malstrom S, Subramanian T, Venkatesh LK, Schaeper U, Elangovan B, D'Sa-Eipper C, Chinnadurai G. Cell. 1994;79:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bokoch GM. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:637–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henis-Korenblit S, Shani G, Sines T, Marash L, Shohat G, Kimchi A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5400–5405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082102499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy JV, Ni J, Dixit VM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16968–16975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatti A, Huang Z, Tuazon PT, Traugh JA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8022–8028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posewitz MC, Tempst P. Anal Chem. 1999;71:2883–2892. doi: 10.1021/ac981409y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nuhse TS, Stensballe A, Jensen ON, Peck SC. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1234–1243. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T300006-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Essader AS, Cargile BJ, Bundy JL, Stephenson JL., Jr Proteomics. 2005;5:24–34. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moritz RL, Ji H, Schutz F, Connolly LM, Kapp EA, Speed TP, Simpson RJ. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4811–4824. doi: 10.1021/ac049717l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Complete lists and descriptions of the phosphopeptides identified in this study are included as supplementary data along with supplementary methods.