Abstract

Bcl-2 is a multifunctional protein that protects against cell death induced by a wide variety of stimuli. The best characterized antiapoptotic Bcl-2 mechanism of action involves direct binding to proapoptotic proteins, e.g., Bax, inhibiting their ability to oligomerize and form pores in the mitochondrial outer membrane, through which soluble mitochondrial proapoptotic proteins, e.g., cytochrome c, are released into the cytosol. Bcl-2 also exerts antiapoptotic and antinecrotic effects that are mediated by its influence on cellular redox state and apparently independent of its interaction with proapoptotic proteins. Bcl-2 expression increases cell resistance to oxidants, augments the expression of intracellular defenses against reactive oxygen species, and may affect mitochondrial generation of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide. This review focuses on the protective effects of Bcl-2 related to changes in mitochondrial redox capacity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 508–514.

INTRODUCTION

THE bcl-2 oncogene was first described in a lymphoblastic leukemia cell line (42, 53) and found to promote cell proliferation, tumor generation, and resistance against cell death (45, 54). The product of this gene, Bcl-2, is an integral membrane protein targeted to the outer mitochondrial membrane (41), although it may also associate with other cellular membranes (16, 19, 38). Overexpression of this protein protects against both apoptotic and necrotic cell death induced by a variety of agents, including chemotherapeutic drugs, irradiation, oxidants, and glutathione depletion (17, 21, 29, 52; see Table 1). The range of cell death protocols in which Bcl-2 is found to be protective is indicative of the multifunctional character of this protein. Indeed, Bcl-2 has been shown to regulate transcription (36, 56), interact with proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, e.g., Bax (31, 43), regulate caspase activation (11, 20), have pore-forming properties (47), alter intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (28, 33, 39), and increase cellular resistance to oxidative stress (10, 17, 22, 25, 40). This review focuses on the redox mechanisms through which Bcl-2 protects against cell death.

Table 1.

Protection Against Oxidative Cell Death by Bcl-2 Family Members

| Cell/animal type | Form of cell death | References |

|---|---|---|

| T cells from bcl-2 transgenic mice | γ radiation, H2O2, menadione | 17, 48, 52 |

| Burkitt's lymphoma cell line transfected with bcl-2 | C6-ceramide, TNF-α, resulting in cellular oxidative stress | 12 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing bcl-2, ced-9, or bcl-xl | Menadione, H2O2 | 6 |

| SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line overexpressing Bcl-xL | H2O2 | 30 |

| T cells transfected with bcl-2 | tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | 59 |

| GT1-7 and PC12 cell lines overexpressing Bcl-2 | Glutathione depletion, menadione, tert-butyl hydroperoxide, cyanide/aglycemia | 21, 40, 61 |

| HeLa, MCF-7, and mouse lymphoma cell lines overexpressing Bcl-2 | Glutathione depletion, γ radiation | 35, 36, 46 |

TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Bcl-2 PROTECTS AGAINST OXIDANT-INDUCED CELL DEATH

The concept that Bcl-2 increases cellular redox capacity was first suggested by Hockenbery et al. (17), based on the observation that this protein is located at the mitochondrion, a primary intracellular site of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. These authors also observed that Bcl-2 protects against cell death induced by oxidants, e.g., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and menadione, in a manner similar to antioxidant molecules and enzymes, e.g., N-acetylcysteine and glutathione peroxidase. Finally, they found that classical apoptotic signals increased cellular lipid peroxidation in a manner prevented by Bcl-2. Their suggestion that Bcl-2 protects against oxidative stress was supported by the finding that Bcl-2 knockout mice displayed a 43% greater level of oxidized brain proteins, 27% fewer cerebellar neurons, and defective melanin synthesis and polycystic kidney disease, phenotypes consistent with chronic oxidative stress (15, 55).

Following these initial findings, many groups demonstrated that Bcl-2 overexpression protects cells against oxidant-mediated damage promoted by γ-irradiation, H2O2, tert-butyl hydroperoxide, cyanide plus glucose deprivation, and ischemia/reperfusion (17, 21, 29, 40, 49, 52, 59; see Table 1). Overexpression of ced-9, the nematode homologue of Bcl-2, or the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL is also protective against oxidative damage and cell death (6), suggesting that this effect is a general role of the antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family.

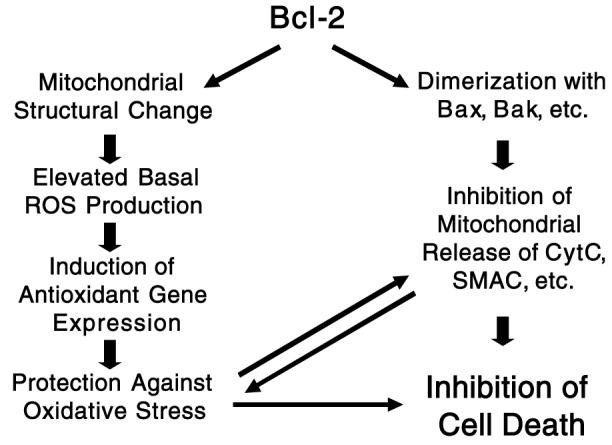

Bcl-2 expression also correlates with protection against the depletion of cellular glutathione (21, 35, 36, 57), a peptide whose sulfhydryl groups serve as the major source of antioxidant reducing power (34). Removing glutathione in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells restores sensitivity to cell death without affecting Bcl-2 levels (1, 36), suggesting that Bcl-2 protects against oxidants indirectly by increasing redox capacity. Some Bcl-2-overexpressing cell lines do, in fact, exhibit elevated levels of H2O2-removing enzymes, e.g., glutathione and thioredoxin peroxidase (10). Moreover, overexpression of these antioxidant systems protects against cell death, independent of Bcl-2 expression levels (14, 60) (See Fig. 1).

FIG. 1. Protection by Bcl-2 against cell death mediated by both anti-Bax and antioxidant mechanisms.

CytC, cytochrome c.

Bcl-2 INCREASES CELLULAR REDOX CAPACITY

The initial observation that Bcl-2 protects against lipid oxidation and cell death promoted by oxidants, but does not inhibit the generation of ROS, suggested an increased ability to remove ROS in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells (17). Subsequent work revealed that Bcl-2-overexpression increased the antioxidant capacity of neural cell lines through elevation of either catalase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, or reduced glutathione and NAD(P)H (10; see Table 2). Mirkovic et al. (36) found that depleting intracellular glutathione reversed the protection conferred by Bcl-2 against radiation-induced apoptosis, suggesting this protection was independent of the presence of the protein itself. The same effect was observed with cells overexpressing Bcl-xL, a protein with antiapoptotic and molecular characteristics similar to Bcl-2 (2). The correlation between Bcl-2, glutathione, and protection against cell death was subsequently well established in many cell death protocols and different Bcl-2-overexpressing cell lines (1, 35, 57; for review, see 56).

Table 2.

Effect of Bcl-2 on Cellular Redox Status

| Cell type | GSSG/(GSSG + GSH) | NAD+/NADH | Catalase | SOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC12 Bcl-2(−) | 0.95 ± 0.10 | 9.8 | 17.0 ± 1.0 | 120 ± 12 |

| PC12 Bcl-2(+) | 0.25 ± 0.15 | 3.0 | 29.0 ± 1.4 | 220 ± 22 |

| GT1-7 Bcl-2(−) | 1.40 ± 0.25 | 34.0 | 34.0 ± 0.6 | 145 ± 10 |

| GT1-7 Bcl-2(+) | 0.70 ± 0.15 | 18.0 | 31.0 ± 0.3 | 164 ± 13 |

Ratios of oxidized over total glutathione [GSSG/(GSSG + GSH)], oxidized over reduced pyridine nucleotides (NAD+/NADH), and catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities (in units/mg of protein) were measured in PC12 and GT1-7 neural cell lines overexpressing Bcl-2. Adapted from reference 10, with permission.

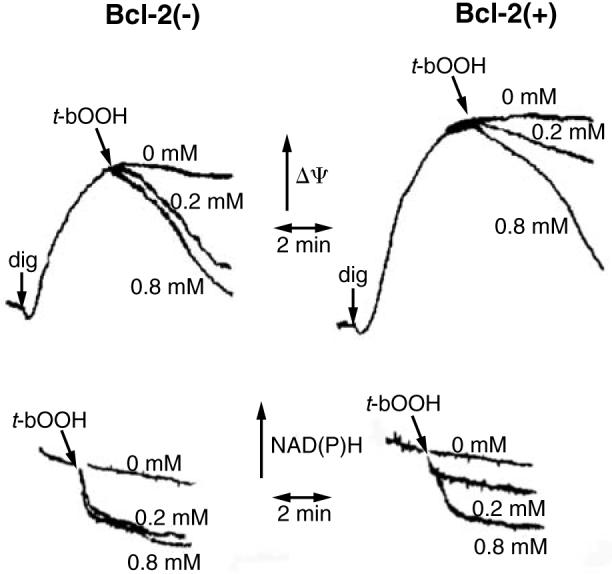

We and others have also found that Bcl-2 overexpression results in increased intracellular and mitochondrial NAD(P)H (10, 12, 22), another important redox source, responsible for the regeneration of reduced glutathione and thioredoxin (see below and 18). In mitochondria, increased levels of NAD(P)H prevent oxidation of inner mitochondrial membrane proteins that modulate the mitochondrial permeability transition (PT) (for review, see 23). The PT causes mitochondrial inner membrane depolarization and uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. Moreover, the net influx of solutes into the mitochondrial matrix through the PT pore causes large amplitude osmotic swelling, rupture of the mitochondrial outer membrane, and release of proapoptotic proteins, e.g., cytochrome c, from their normal exclusive location within the space between the inner and outer membranes (5, 7, 32, 63). Consequently, PT may trigger necrosis or “accidental apoptosis,” such as that which occurs when a necrotic event is insufficiently powerful to lead to immediate cell death, but sufficient to activate apoptotic pathways, e.g., release of proapoptotic proteins from mitochondria (8). In Bcl-2-overexpressing cells, PT is inhibited (22, 32, 49). The mechanism by which Bcl-2 inhibits the PT is indirect and mediated by a resistance of mitochondrial NAD(P)H to undergo oxidation in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells. Thus, we demonstrated that, in the presence of a relatively low concentration of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (0.2 mM), NAD(P)H is oxidized and PT occurs in wild-type GT1–7 neural cells, but neither event is observed in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells (Fig. 2) (22). However, when digitonin-permeabilized cells are exposed to a high concentration of tert-butyl hydroperoxide (0.8 mM), mitochondria within both normal and Bcl-2-overexpressing cells undergo the PT in response to extensive NAD(P)H oxidation. The sensitivity of wild-type cell mitochondria to PT is decreased and therefore similar to that of Bcl-2 mitochondria when exogenous reducing power is used to minimize the oxidation of NAD(P)H caused by the peroxide. These findings are in agreement with the observation that although Bcl-2 protects against PT and cell death promoted by tert-butyl hydroperoxide, a NAD(P)H oxidant, Bcl-2 is ineffective against thiol cross-linking agents, e.g., diamide and phenylarsine oxide, that directly oxidize thiol groups responsible for PT opening in a manner independent of NAD(P)H redox state (22, 59).

FIG. 2. Bcl-2(+) mitochondria in digitonin (dig)-permeabilized PC12 cells are more resistant to membrane potential (Δψ) decreases (upper panels) and NAD(P)H oxidation (lower panels) promoted by tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-bOOH), added at the concentrations indicated.

Adapted from reference 22, with permission.

The molecular mechanism by which Bcl-2 increases mitochondrial and cellular redox capacity remains unknown. However, the observation that different cell lines overexpressing Bcl-2 exhibit different patterns of elevated antioxidant defense systems (10) suggests that these phenotypes are a general response to effects of Bcl-2 on the normal intracellular environment, rather than a direct regulation of the transcription of these proteins by Bcl-2.

HOW DOES Bcl-2 INCREASE REDOX CAPACITY?

Although the increased redox capacity of Bcl-2-overexpressing cells is well established, the cause of this increased antioxidant expression is still poorly understood. One approach to this problem is to assess the regulatory mechanisms responsible for determining the expression of redox-related genes, and to determine what relationship they may have to Bcl-2 expression.

The p53 tumor-suppressing gene is a well-known regulator of redox-related genes (44) and promotes cellular formation of ROS and cell death. Moreover, p53 acts upstream of Bcl-2 expression (37), and therefore it is highly unlikely that antioxidants are increased in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells due to p53 down-regulation. There is also no evidence that Bcl-2 regulates gene transcription by any mechanism other than its effects on glutathione levels and distribution (56). Therefore, it is probable that Bcl-2 alters some other cellular parameter, which then affects glutathione synthesis and redox-related gene expression.

Another known regulator of cellular redox capacity is local oxygen tension (3, 27, 62). As Bcl-2 is a mitochondrial protein, it could potentially affect respiration and therefore intracellular oxygen tension, resulting in changes in antioxidant levels. However, experiments conducted by our group and others have not observed any significant differences in the quantity of mitochondria or rates of respiration in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells (39, 49).

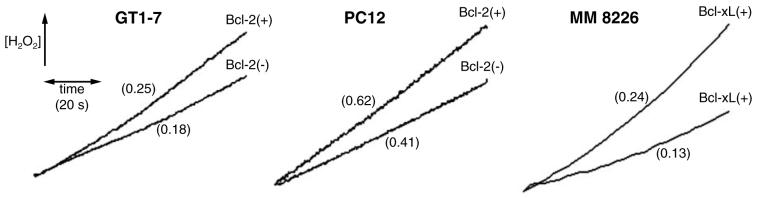

Antioxidant proteins are also expressed in response to increased production of intracellular H2O2 (9, 13). Although the increase in ROS generation that occurs in response to apoptotic stimuli is blunted in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells (5, 17, 21, 58), the effects of Bcl-2 on steady-state mitochondrial H2O2 release under physiological conditions are not well characterized. Hockenbery et al. (17) did not find any differences in ROS release in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells. However, other publications reported that Bcl-2-overexpressing cells generate more ROS than Bcl-2(−) controls under physiological conditions (1, 12). Indeed, we have also found that mitochondria isolated from Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL-overexpressing cells generate higher rates of H2O2 (Fig. 3). Esposti et al. (12) suggested that the lack of previous detection of higher levels of ROS release in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells was due to the use of less sensitive probes. We have also found (25) that the presence of higher intracellular antioxidant levels in Bcl-2(+) cells can compensate for higher mitochondrial ROS release, resulting in the detection of similar ROS levels in intact cells.

FIG. 3. Mitochondria isolated from GT1-7, PC12, and MM 8226 cells (as shown) were incubated in the presence of NADH-linked substrates and oligomycin, under experimental conditions similar to those described in references 24 and 25.

H2O2 release was measured by following Amplex red oxidation in the presence of horseradish peroxidase, as described in references 25 and 50. Numbers in parentheses indicate H2O2 release rates, in nmol/min/mg of protein.

The presence of chronically higher levels of mitochondrially generated ROS could certainly account for the larger expression of antioxidants in Bcl-2(+) cells. As a result, these cells are protected against acute oxidative insults, and exhibit lower ROS accumulation when subjected to conditions that normally lead to oxidative stress (5, 17, 21, 58). However, the mechanism through which Bcl-2 increases mitochondrial ROS release is undetermined.

POSSIBLE MECHANISMS BY WHICH Bcl-2 INCREASES MITOCHONDRIAL ROS PRODUCTION

Esposti et al. (12) correlated the increase in ROS measured in Bcl-2(+) cells with increased NAD(P)H levels, a finding compatible with data from our group indicating that Bcl-2(+) cells and mitochondria contain larger quantities of NAD(P)H (10, 22). Armstrong and Jones (1) found that rotenone increased ROS release levels, a result also compatible with a significant role of NADH. Rotenone leads to the accumulation of electrons removed from NADH in the iron-sulfur centers of the mitochondrial electron transport chain Complex I, increasing superoxide radical formation at or prior to this site (4). Recent work performed with highly sensitive fluorescent probes for H2O2 indicates that even in the absence of Complex I inhibition, NADH-dependent respiration supports significant mitochondrial ROS production regulated by both NADH redox state and mitochondrial membrane potential (26, 50). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that elevated mitochondrial NAD(P)H redox state in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells is caused by altered electron transport chain dynamics.

Mitochondrial NADH redox state is intimately related to the inner membrane potential and respiratory rates. No differences in respiratory rates between Bcl-2(+) and Bcl-2(−) mitochondria are apparent. However, Bcl-2(+) mitochondria accumulate greater quantities of membrane-potential probes, a finding initially interpreted as an indication of larger inner membrane potentials (22, 49). We recently reported that the membrane potential is identical in Bcl-2(+) and Bcl-2(−) mitochondria, but that these mitochondria respond differently to membrane potential probes (24). Flow cytometry measurements indicate that Bcl-2 expression results in increased mitochondrial size and membrane structural complexity, possibly reflecting larger membrane content. These structural differences explain the altered response these mitochondria exhibit in response to membrane potential probes (24).

A change in mitochondrial size and membrane content may also explain the increased NADH levels and ROS release in Bcl-2(+) cells. It is possible that Bcl-2 expression results in an increased ratio of mitochondrial matrix volume/membrane surface area, which could explain higher total matrix NAD(H) with equal respiratory activity. Under these conditions, the presence of higher levels of electron donors with equal electron transport rates could increase the probability of electron leakage at the respiratory chain or other mitochondrial redox sites, generating superoxide radicals and other ROS. A larger mitochondrial matrix volume could also support higher quantities of matrix enzymes, such as pyruvate, α-ketoglutarate, malate, glutamate, and isocitrate dehydrogenases, which could lead to more rapid NADH synthesis. Indeed, Bcl-2(+) mitochondria not only present increased total quantities of NADH and NAD+, but also are more resistant to NADH oxidation (22). Based on these results and suppositions, we propose that increased NADH levels, possibly attributable to a larger matrix volume in Bcl-2(+) mitochondria, cause a subtoxic increase in mitochondrial ROS generation, ultimately increasing antioxidant capacity in Bcl-2(+) mitochondria and cells.

SUMMARY

The proposed effects of Bcl-2 on mitochondrial redox capacity, sensitivity to PT, release of cytochrome c caused by Bax or PT, and the relationship of these effects to cytoprotection are summarized in Fig. 1. Bcl-2 can inhibit the release of cytochrome c and other proapoptotic mitochondrial proteins by two mechanisms. One involves a direct interaction with proapoptotic proteins, e.g., Bax and Bad, that localize or redistribute to the mitochondrial outer membrane. The other mechanism of inhibition is suppression of outer membrane disruption caused by the PT. Inhibition of PT by Bcl-2 is due to the increase in mitochondrial redox capacity afforded by Bcl-2 expression. In addition to decreasing the sensitivity of mitochondria to oxidant-induced PT, the increased redox capacity can protect against either necrotic or apoptotic cell death induced by oxidative stress through detoxification of ROS via glutathione reductase/peroxidase and other antioxidant systems. Finally, the dual mechanisms for inhibition of cytochrome c release by Bcl-2 also indirectly inhibit oxidative stress as extensive loss of cytochrome c results in a dramatic accumulation of electrons within mitochondrial redox components and stimulation of mitochondrial ROS generation (5, 26, 51).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo àPesquisa no Estado de São Paulo, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (A.J.K.) and by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grants NS34152, ES11838, and NS45038 (G.F.). The authors would like to thank Prof. Robert G. Fenton for providing Bcl-xL(−) and Bcl-xL(+) MM 8226 cells.

ABBREVIATIONS

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- PT

permeability transition

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong JS, Jones DP. Glutathione depletion enforces the mitochondrial permeability transition and causes cell death in Bcl-2 overexpressing HL60 cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:1263–1265. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0097fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bojes HK, Datta K, Xu J, Chin A, Simonian P, Nunez G, Kehrer JP. Bcl-xL overexpression attenuates glutathione depletion in FL5.12 cells following interleukin-3 withdrawal. Biochem J. 1997;325:315–319. doi: 10.1042/bj3250315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunn HF, Poyton RO. Oxygen sensing and molecular adaptation to hypoxia. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:839–885. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, Stoppani AO. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;180:248–257. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai J, Jones DP. Superoxide in apoptosis. Mitochondrial generation triggered by cytochrome c loss. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11401–11404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen SR, Dunigan DD, Dickman MB. Bcl-2 family members inhibit oxidative stress-induced programmed cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1315–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colell A, Garcia-Ruiz C, Lluis JM, Coll O, Mari M, Fernandez-Checa JC. Cholesterol impairs the adenine nucleotide translocator-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition through altered membrane fluidity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33928–33935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341:233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demasi AP, Pereira GA, Netto LES. Cytosolic thioredoxin peroxidase I is essential for the antioxidant defense of yeast with dysfunctional mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2001;509:430–434. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Park SM, Holleran AL, Murphy AN, Fiskum G, Kane DJ, Testa MP, Kayalar C, Bredesen DE. Shift of the cellular oxidation-reduction potential in neural cells expressing Bcl-2. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1259–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67031259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enari M, Hase A, Nagata S. Apoptosis by a cytosolic extract from Fas-activated cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:5201–5208. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposti MD, Hatzinisiriou I, McLennan H, Ralph S. Bcl-2 and mitochondrial oxygen radicals. New approaches with reactive oxygen species-sensitive probes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29831–29837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godon C, Lagniel G, Lee J, Buhler JM, Kieffer S, Perrot M, Boucherie H, Toledano MB, Labarre J. The H2O2 stimulon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22480–22489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouaze V, Andrieu-Abadie N, Cuvillier O, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Frisach MF, Mirault ME, Levade T. Glutathione peroxidase-1 protects from CD95-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42867–42874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochman A, Sternin H, Gorodin S, Korsmeyer S, Ziv I, Melamed E, Offen D. Enhanced oxidative stress and altered antioxidants in brains of Bcl-2-deficient mice. J Neurochem. 1998;71:741–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hockenbery DM, Nunez G, Milliman C, Schreiber RD, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmgren A. Antioxidant function of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:811–820. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.4-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson MD, Burne JF, King MP, Miyashita T, Reed JC, Raff MC. Bcl-2 blocks apoptosis in cells lacking mitochondrial DNA. Nature. 1993;361:365–369. doi: 10.1038/361365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobsen MD, Weil M, Raff MC. Role of Ced-3/ICE-family proteases in staurosporine-induced programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1041–1051. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.5.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane DJ, Sarafian TA, Anton R, Hahn H, Gralla EB, Valentine JS, Ord T, Bredesen DE. Bcl-2 inhibition of neural death: decreased generation of reactive oxygen species. Science. 1993;262:1274–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.8235659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowaltowski AJ, Vercesi AE, Fiskum G. Bcl-2 prevents mitochondrial permeability transition and cytochrome c release via maintenance of reduced pyridine nucleotides. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:903–910. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kowaltowski AJ, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondrial permeability transition and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:12–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kowaltowski AJ, Cosso RG, Campos CB, Fiskum G. Effect of Bcl-2 overexpression on mitochondrial structure and function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42802–42807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowaltowski AJ, Fenton RG, Fiskum G. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate mitochondrial reactive oxygen production and protect against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1845–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kushnareva Y, Murphy AN, Andreyev A. Complex I-mediated reactive oxygen species generation: modulation by cytochrome c and NAD(P)+ oxidation–reduction state. Biochem J. 2002;368:545–553. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwast KE, Burke PV, Staahl BT, Poyton RO. Oxygen sensing in yeast: evidence for the involvement of the respiratory chain in regulating the transcription of a subset of hypoxic genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5446–5451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam M, Dubyak G, Chen L, Nunez G, Miesfeld RL, Distelhorst CW. Evidence that BCL-2 represses apoptosis by regulating endoplasmic reticulum-associated Ca2+ fluxes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6569–6573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lotem J, Sachs L. Regulation by bcl-2, c-myc, and p53 of susceptibility to induction of apoptosis by heat shock and cancer chemotherapy compounds in differentiation-competent and -defective myeloid leukemic cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luetjens CM, Lankiewicz S, Bui NT, Krohn AJ, Poppe M, Prehn JH. Up-regulation of Bcl-xL in response to subtoxic beta-amyloid: role in neuronal resistance against apoptotic and oxidative injury. Neuroscience. 2001;102:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahajan NP, Linder K, Berry G, Gordon GW, Heim R, Herman B. Bcl-2 and Bax interactions in mitochondria probed with green fluorescent protein and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:547–552. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchetti P, Castedo M, Susin SA, Zamzami N, Hirsch T, Macho A, Haeffner A, Hirsch F, Geuskens M, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial permeability transition is a central coordinating event of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1155–1160. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marin MC, Fernandez A, Bick RJ, Brisbay S, Buja LM, Snuggs M, McConkey DJ, von Eschenbach AC, Keating MJ, McDonnell TJ. Apoptosis suppression by bcl-2 is correlated with the regulation of nuclear and cytosolic Ca2+ Oncogene. 1996;12:2259–2266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meredith MJ, Cusick CL, Soltaninassab S, Sekhar KS, Lu S, Freeman ML. Expression of Bcl-2 increases intracellular glutathione by inhibiting methionine-dependent GSH efflux. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:458–463. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirkovic N, Voehringer DW, Story MD, McConkey DJ, McDonnell TJ, Meyn RE. Resistance to radiation-induced apoptosis in Bcl-2-expressing cells is reversed by depleting cellular thiols. Oncogene. 1997;15:1461–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Wang HG, Lin HK, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monaghan P, Robertson D, Amos TA, Dyer MJ, Mason DY, Greaves MF. Ultrastructural localization of bcl-2 protein. J Histochem Cytochem. 1992;40:1819–1825. doi: 10.1177/40.12.1453000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy AN, Bredesen DE, Cortopassi G, Wang E, Fiskum G. Bcl-2 potentiates the maximal calcium uptake capacity of neural cell mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9893–9898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myers KM, Fiskum G, Liu Y, Simmens SJ, Bredesen DE, Murphy AN. Bcl-2 protects neural cells from cyanide/aglycemia-induced lipid oxidation, mitochondrial injury, and loss of viability. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2432–2440. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen M, Millar DG, Yong VW, Korsmeyer SJ, Shore GC. Targeting of Bcl-2 to the mitochondrial outer membrane by a COOH-terminal signal anchor sequence. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:25265–25268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pegoraro L, Palumbo A, Erikson J, Falda M, Giovanazzo B, Emanuel BS, Rovera G, Nowell PC, Croce CM. A 14;18 and an 8;14 chromosome translocation in a cell line derived from an acute B-cell leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:7166–7170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polster BM, Kinnally KW, Fiskum G. BH3 death domain peptide induces cell type-selective mitochondrial outer membrane permeability. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37887–37894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389:300–305. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed JC, Cuddy M, Slabiak T, Croce CM, Nowell PC. Oncogenic potential of bcl-2 demonstrated by gene transfer. Nature. 1988;336:259–261. doi: 10.1038/336259a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudin CM, Yang Z, Schumaker LM, Vander Weele DJ, Newkirk K, Egorin MJ, Zuhowski EG, Cullen KJ. Inhibition of glutathione synthesis reverses Bcl-2-mediated cisplatin resistance. Cancer Res. 2003;63:312–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schendel SL, Xie Z, Montal MO, Matsuyama S, Montal M, Reed JC. Channel formation by antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5113–5118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sentman CL, Shutter JR, Hockenbery D, Kanagawa O, Korsmeyer SJ. bcl-2 inhibits multiple forms of apoptosis but not negative selection in thymocytes. Cell. 1991;67:879–888. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kamiike W, Funahashi Y, Mignon A, Lacronique V, Matsuda H, Tsujimoto Y. Bcl-2 prevents apoptotic mitochondrial dysfunction by regulating proton flux. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1455–1459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Starkov AA, Fiskum G. Regulation of brain mitochondrial H2O2 production by membrane potential and NAD(P)H redox state. J Neurochem. 2003;86:1101–1107. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Starkov AA, Polster BM, Fiskum G. Regulation of hydrogen peroxide production by brain mitochondria by calcium and Bax. J Neurochem. 2002;83:220–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strasser A, Harris AW, Cory S. bcl-2 transgene inhibits T cell death and perturbs thymic self-censorship. Cell. 1991;67:889–899. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsujimoto Y, Finger LR, Yunis J, Nowell PC, Croce CM. Cloning of the chromosome breakpoint of neoplastic B cells with the t(14;18) chromosome translocation. Science. 1984;226:1097–1099. doi: 10.1126/science.6093263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaux DL, Cory S, Adams JM. Bcl-2 gene promotes haemopoietic cell survival and cooperates with c-myc to immortalize pre-B cells. Nature. 1988;335:440–442. doi: 10.1038/335440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veis DJ, Sorenson CM, Shutter JR, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell. 1993;75:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80065-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voehringer DW. BCL-2 and glutathione: alterations in cellular redox state that regulate apoptosis sensitivity. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:945–950. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voehringer DW, McConkey DJ, McDonnell TJ, Brisbay S, Meyn RE. Bcl-2 expression causes redistribution of glutathione to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2956–2960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zamzami N, Marchetti P, Castedo M, Decaudin D, Macho A, Hirsch T, Susin SA, Petit PX, Mignotte B, Kroemer G. Sequential reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and generation of reactive oxygen species in early programmed cell death. J Exp Med. 1995;182:367–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zamzami N, Marzo I, Susin SA, Brenner C, Larochette N, Marchetti P, Reed J, Kofler R, Kroemer G. The thiol crosslinking agent diamide overcomes the apoptosis-inhibitory effect of Bcl-2 by enforcing mitochondrial permeability transition. Oncogene. 1998;16:1055–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang P, Liu B, Kang SW, Seo MS, Rhee SG, Obeid LM. Thioredoxin peroxidase is a novel inhibitor of apoptosis with a mechanism distinct from that of Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30615–30618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhong LT, Sarafian T, Kane DJ, Charles AC, Mah SP, Edwards RH, Bredesen DE. bcl-2 inhibits death of central neural cells induced by multiple agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4533–4537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zitomer RS, Lowry CV. Regulation of gene expression by oxygen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.1-11.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zoratti M, Szabo I. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:139–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]