Abstract

Purpose

IL-21 is a promising new cytokine, which is undergoing clinical testing as an anti-cancer agent. Although IL-21 provides potent stimulation of CD8+ T cells, it has also been suggested that IL-21 is immunosuppressive by counteracting the maturation of dendritic cells (DC). Dissociation of these two opposing effects may enhance the utility of IL-21 as an immunotherapeutic. In this study, we employed a cell-based artificial antigen-presenting cell (aAPC) lacking a functional IL-21R to investigate the immunostimulatory properties of IL-21.

Experimental Design

Immunosuppressive activity of IL-21 was studied using human IL-21R+ DC. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells stimulated with human cell-based IL-21R- aAPC were used to isolate the T cell immunostimulatory effects of IL-21. Functional outcomes including phenotype, cytokine production, proliferation and cytotoxicity were evaluated.

Results

IL-21 limits the immune response by maintaining immunologically immature DC. However, stimulation of CD8+ T cells with IL-21R- aAPC, which secrete IL-21 results in significant expansion. Although priming in the presence of IL-21 temporarily modulated the T cell phenotype, chronic stimulation abrogated these differences. Importantly, exposure to IL-21 during restimulation promoted the enrichment and expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells which maintained IL-2 secretion and gained enhanced interferon-γ secretion. Tumor antigen-specific CTL generated in the presence of IL-21 recognized tumor cells efficiently, demonstrating potent effector functions.

Conclusions

IL-21 induces opposing effects on APC and CD8+ T cells. Strategic application of IL-21 is required to induce optimal clinical effects and may enable the generation of large numbers of highly avid tumor-specific CTL for adoptive immunotherapy. (250 words)

Introduction

Recent clinical success associated with the adoptive transfer of anti-tumor reactive T cells support the potential impact of this significant clinical modality(1-3). In order to generate clinically effective tumor-specific CD8+ T cells ex vivo, two components are crucially important; antigen-presenting cells (APC) and T cell growth factors. Dynamic APC-CD8+ T cell interactions drive CD8+ T cell proliferation and differentiation, resulting in the generation of CTL that have diverse phenotypic and functional characteristics. Several autologous APC such as dendritic cells (DC), CD40 ligand activated B cells, EBV-lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL), and a number of artificial APC have been used to deliver T cell receptor (TCR) engagement and multiple costimulatory and inhibitory signals(4-7).

Once T cells are properly stimulated by APC, CD8+ T cells require growth factors such as IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15, which belong to the common γ chain receptor cytokine family, for their expansion and lineage commitment(8). IL-2 has been employed extensively by many investigators for the expansion of T cells, and, importantly, has become part of the clinical management of melanoma patients(9). However, accumulating evidence both in vivo and in vitro suggests that IL-2 also plays a major role in the expansion of regulatory T cells, which inhibit the effector function of anti-tumor T cells(10, 11). It has been suggested that IL-7 is important for the maintenance of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells(12, 13). A recent clinical trial has demonstrated that IL-7 administration in humans results in a rapid and selective increase in circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells(14). IL-15 has also commonly been used for the expansion of T cells ex vivo. In stark contrast to IL-2, which induces activation-induced cell death, IL-15 is an anti-apoptotic factor for many cell types(15). Studies of IL-15 null mice strongly support the requirement of IL-15 for CD8+ T cell expansion(15). In mice, IL-15 directs CD8+ T cells to preferentially differentiate into central memory T cells whereas IL-2 promotes differentiation into effector memory T cells(16).

IL-21 is the newest member of the common γ chain receptor cytokine family and is closely related to IL-2 and IL-15(17). In vitro and in vivo data suggest that IL-21 plays an important immunostimulatory role by modulating T, B, and NK cell mediated immunity(18-20). Using APC such as DC, it has been shown in vitro that IL-21 can enhance the generation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with potent effector function(21). Furthermore, the expansion and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells were impaired in IL-21R-/- mice(22, 23). It is not known whether IL-21 acts by directly stimulating CD8+ T cells or by first modulating the APC, which in turn induces a superior T cell response. Either scenario is possible since, while IL-21 is secreted predominantly by activated CD4+ T cells, the IL-21 receptor (IL-21R) is widely expressed by various lineages of immune cells including both T cells and antigen-presenting cells.

Other data, however, suggests that the immunostimulatory role for IL-21 may be limited via immunosuppressive effects on APC. While not fully established in humans, murine studies support an immunosuppressive role for IL-21 since in vitro it inhibits the maturation of DC and their capacity to stimulate T cells(24). Therefore, the impact of IL-21 may be dependent on whether exposure to IL-21 occurs prior to or following the initial establishment of an immune response. Understanding the mechanisms of IL-21 mediated immunomodulation in humans is of critical importance clinically since a favorable immune response may be significantly affected by the schedule and dose of IL-21 administered both in vivo and ex vivo.

In this study, we have demonstrated in the human that IL-21 induces dichotomous immunological effects on DC and CD8+ T cells. On the one hand, we show in human cells that IL-21 inhibits the maturation and T cell stimulatory activity of DC. On the other, we conclusively show that IL-21 can act directly on lymphocytes and significantly enhance the generation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by using a novel APC which does not express IL-21R. These results demonstrate the importance of dissecting the opposing immunological effects of IL-21: immunosuppression of DC and immunostimulation of CTL.

Materials and Methods

cDNAs

Human IL-21 and IL-21 receptor (IL-21R) cDNA were cloned from normal PBMC by RT-PCR based upon the published sequences. IL-21 cDNA was tandemly fused to IRES-EGFP sequence and ligated to the pMX vector. IL-21R cDNA was cloned into pMXpuro. All the DNA constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Cells

K562 based aAPC expressing HLA-A2, CD80 and CD83 has been reported previously(25). To generate aAPC/IL-21, aAPC was retrovirally transduced with IL-21 and EGFP, and flow cytometry was used to sort EGFP positive cells. Polyclonal cell lines consisting of at least 104 independent clones were used to prevent cloning induced variations.

The mouse IL-3-dependent pro-B lymphoid cell line BaF3 (a gift from James Griffin, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) was infected with retrovirus encoding human IL-21R as well as a puromycin resistance gene. After drug selection, BaF3/IL-21R cells were enriched by specific antibody staining followed by magnetic bead guided sorting (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). BaF3/puro, a control cell line transduced with vector alone, was generated by drug selection.

Purified CD8+ T cells were stimulated by 10-20 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 1 μg/ml calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma-Aldrich) or plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (26). Immature and mature DC were generated as reported previously(26, 27). Where indicated, recombinant human IL-21 (rIL-21) (50 ng/ml) was added to immature DC in addition to IL-4 (10 ng/ml) and GM-CSF (50 ng/ml) every two days. Maturation was induced with double-stranded RNA (25 μg/ml) and TNF-α (50 ng/ml) on day 6.

Flow cytometry analysis

mAbs recognizing the following antigens were used: CD54, CD58, CD80, CD83 and CD86 from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); CD45RA, CD45RO, CD28 and CD62L from Beckman Coulter (Miami, FL); HLA-class I, HLA-DR, CD27 from Caltag (Burlingame, CA); CCR7 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); and mouse isotype controls from BD Biosciences and Beckman Coulter. To detect human IL-21R expression, goat anti-human IL-21R Ab or mouse anti-human IL-21R mAb (R&D) and appropriate PE-conjugated secondary Abs (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) were employed. Surface molecule staining was performed as described elsewhere(27). In order to avoid detecting the phenotypic changes simply related to the T cell activation following TCR engagement and costimulation, all phenotypic analyses of antigen-specific T cells were performed at least 7 days after the last stimulation unless indicated otherwise.

Production of HLA class I peptide-specific CD8+ T cells

Peripheral blood samples from normal donors were collected in compliance with protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Peptide-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell lines were generated as described previously(25-28). Briefly, aAPC and aAPC/IL-21 cells were pulsed with synthetic peptide (58GILGFVFTL66 of the influenza virus matrix antigen at 0.1 μg/ml, 27AAGIGILTV35 of MART1 or 85ELTLGEFLKL94 of survivin both at 10 μg/ml; (New England Peptides, Fitchburg, MA)) for 6 hours at room temperature. APC were then irradiated, washed, and added to CD8+ T cells (1:20 APC:T cells). Between stimulations, IL-2 (10 IU/ml; Chiron, Emeryville, CA) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) were added to the cultures unless indicated otherwise.

HLA/peptide multimer analysis

HLA/peptide multimer analysis was performed as described previously(25-28). HLA/peptide multimer was generated in-house or purchased from ProImmune (Oxford, United Kingdom).

Endocytic activity assay

Endocytosis was measured as the cellular uptake of FITC-dextran and was quantified by flow cytometry. Briefly, DC were incubated with FITC-dextran (1 mg/ml; molecular weight 3,000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 10, 30, or 60 min. After incubation, cells were washed twice with cold PBS to stop endocytosis and to remove excess dextran.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity assay was performed as described previously(25-28).

Intracellular cytokine release assay

T cells were cocultured with peptide-loaded T2 cells at the ratio of 4:1 for six hours in the presence of 10 μg/ml brefeldin-A. Cells were then collected, washed, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with PC5-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb (Beckman Coulter), FITC-conjugated anti-IFN-γ and PE-conjugated anti-IL-2 (BD Biosciences).

Cell proliferation assay

Duplicates of BaF3/IL-21R cells were plated in 96-well plates at 50,000/well. Serially increasing concentrations of rIL-21 (0-400 ng/ml) or conditioned medium of aAPC or aAPC/IL-21 were added to the cells. Cells without rIL-21 or conditioned medium were used to assess the baseline growth for the duration of the assay. After incubation for 6 hours at 37°C, each well was pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), and plates were collected and counted 18 hours later.

Purified CD8+ T cells from allogeneic healthy donors were cocultured with irradiated immature or mature DC generated in the presence or absence of IL-21. After incubation for 72 hours at 37°C, each well was pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]thymidine, and plates were collected and counted 18 hours later.

Statistical analysis

Allogeneic T cell proliferation was analyzed as a ratio of responses to the following APC: mature vs. immature DC, mature DC without vs. with IL-21, and immature DC without vs. with IL-21. T cell data was analyzed as the ratio of CD8+ T cells, and the percentage and total number of MART1-specific CTL generated with aAPC/IL-21 compared to aAPC. The one-sided Student's t test was used to assess whether proliferation was significantly reduced with IL-21 treatment or was increased with DC maturation. Similarly, an increase in T cell generation was assessed following IL-21 treatment. All statistical tests were conducted at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

IL-21R is expressed by activated T cells and DC

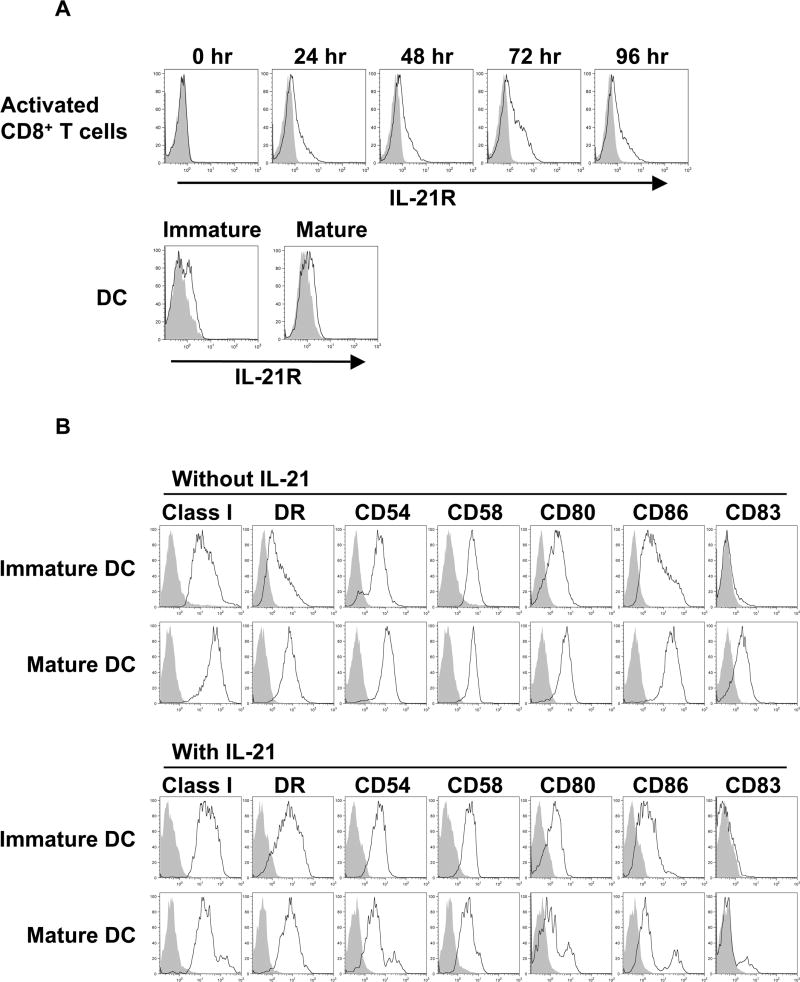

Others have reported that IL-21R is expressed by T cells as well as by APC such as DC and activated B cells(17, 24). Purified CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were optimally stimulated and cell surface IL-21R expression was studied every 24 hrs. IL-21R expression was absent on resting CD8+ T cells and was upregulated upon stimulation (Figure 1A). Maximal expression was observed after either 72 or 96 hrs depending on donors. We next evaluated the expression of IL-21R on DC. Immature DC were generated from peripheral blood monocytes in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. To obtain mature DC, we used TNF-α and double-stranded RNA, a combination which has been shown to be a potent method of DC activation(29). As shown in Figure 1A, IL-21R was expressed by both immature and mature DC at the protein level, suggesting that IL-21 may modulate the phenotype and function of DC.

Figure 1. IL-21 counteracts the full maturation of DC.

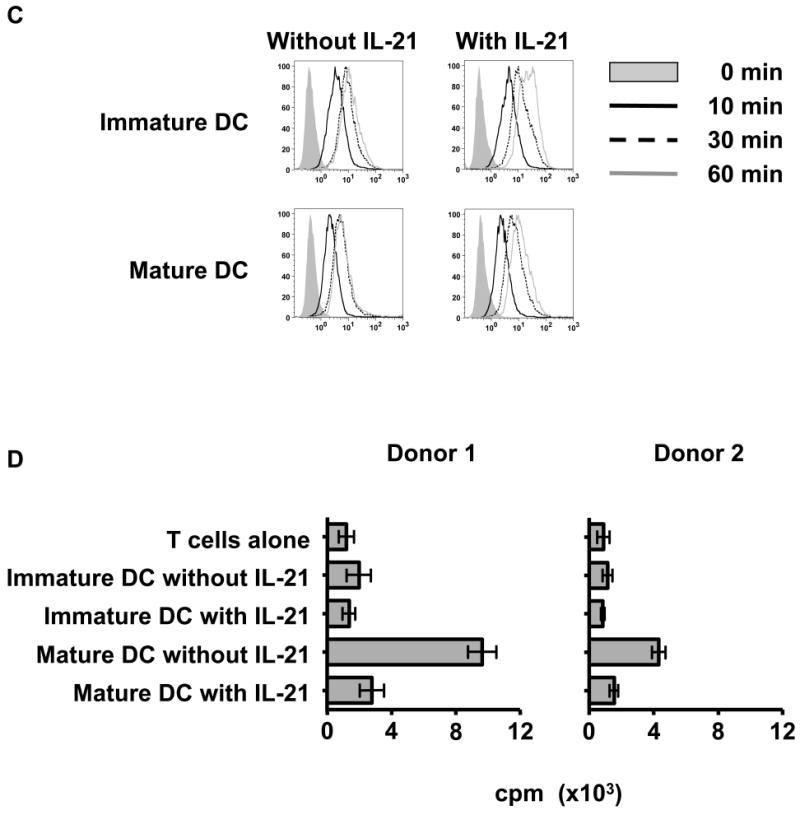

(A) IL-21R is not expressed on resting CD8+ T cells but induced upon activation by phorbol myristate acetate and calcium ionophore A23187. In contrast, DC constitutively express IL-21R. Surface expression of IL-21R on purified CD8+ T cells, immature, and mature DC from healthy donors was determined by flow cytometry with specific antibody (open curves) and isotype control (shaded curves). One result of at least 6 (CD8+ T cells) and 4 (DC) independent experiments is shown. (B) IL-21 inhibits the upregulation of adhesion and costimulatory molecules by DC upon exposure to maturation signals. Immature DC were generated from purified monocytes using IL-4 and GM-CSF. Where indicated, DC cultures were also supplemented with rIL-21 at 50 ng/ml every two days. Surface phenotype of immature and mature DC generated in the presence or absence of IL-21 is shown. Open curves, staining for indicated molecules; shaded curves, isotype controls. A representative result of 4 independent experiments is given. (C) IL-21 enhances the endocytic activity of DC. Endocytic activity of immature and mature DC generated in the presence or absence of IL-21 was measured by FITC-dextran uptake and quantified by flow cytometry. Note that DC lose endocytic activity in response to maturation signals despite the presence of IL-21. Shaded curve, 0 min; solid black line, 10 min; dashed line, 30 min; solid grey line, 60 min. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results. (D) T cell stimulatory capacity of IL-21 treated mature DC is markedly suppressed. Purified CD8+ T cells from four healthy donors were cocultured with irradiated allogeneic immature or mature DC that had been generated in the absence or presence of IL-21. Allogeneic CD8+ T cell response was measured using a standard [3H]thymidine proliferation assay. Results from 2 representative donors are shown, and each value displayed is the average of six replicates (±SD). Note that since purified CD8+ T cells are used as responders, the measured values are lower in comparison to values typically obtained when CD4+ or CD3+ T cells are used as responder cells. However, the results obtained for CD8+ T cell proliferation in this assay are reproducible.

IL-21 mediates immunosuppression of human DC by counteracting maturation

Next we investigated the effect of IL-21 treatment on the phenotype of immature and mature DC (Figure 1B). On immature DC, IL-21 treatment consistently suppressed CD86 expression as previously observed in the mouse. In contrast to the mouse, however, IL-21 treatment consistently increased the expression of HLA-DR suggesting that IL-21 selectively modulates the DC phenotype. When DC were exposed to maturation signals, significant differences were observed. Maturation induced upregulation of adhesion molecules (CD54 and CD58), costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) and the maturation marker, CD83, was inhibited when DC were generated in the presence of IL-21. In contrast, the increased HLA-DR expression was retained, further demonstrating selective modulation by IL-21. It should be noted that the viability of DC was not affected by IL-21 treatment. These results suggest that IL-21 may block the maturation of DC by counteracting maturation signals.

We studied the effect of IL-21 treatment on DC function. Consistent with an increased capacity to take up antigen, exposure to IL-21 enhances the endocytic activity of immature DC. However, IL-21 did not inhibit the ability of maturation signals to downregulate DC endocytic activity levels observed in cells not treated with IL-21 (Figure 1C). Next we evaluated the ability of DC treated with or without IL-21 to stimulate CD8+ T cells. Allogeneic CD8+ T cells from normal donors were stimulated with irradiated DC, and the allogeneic response was measured. As expected, significantly higher proliferation was induced with mature than with immature DC by an average of 3.4 fold (1.3-4.9, P=0.02). As predicted by the failed induction of immunostimulatory molecules on IL-21 treated mature DC, significant suppression of proliferation by allogeneic CD8+ was observed so that proliferation induced by untreated mature DC was 2.7 fold higher (1.6-3.5, P=0.01) than by IL-21 treated mature DC (Figure 1D). IL-21 treatment of immature DC did not significantly reduce proliferation. Taken together, these results suggest that DC express a functional IL-21R and that IL-21 signaling blocks the immunogenicity of DC by suppressing the maturation signal induced upregulation of costimulatory molecules.

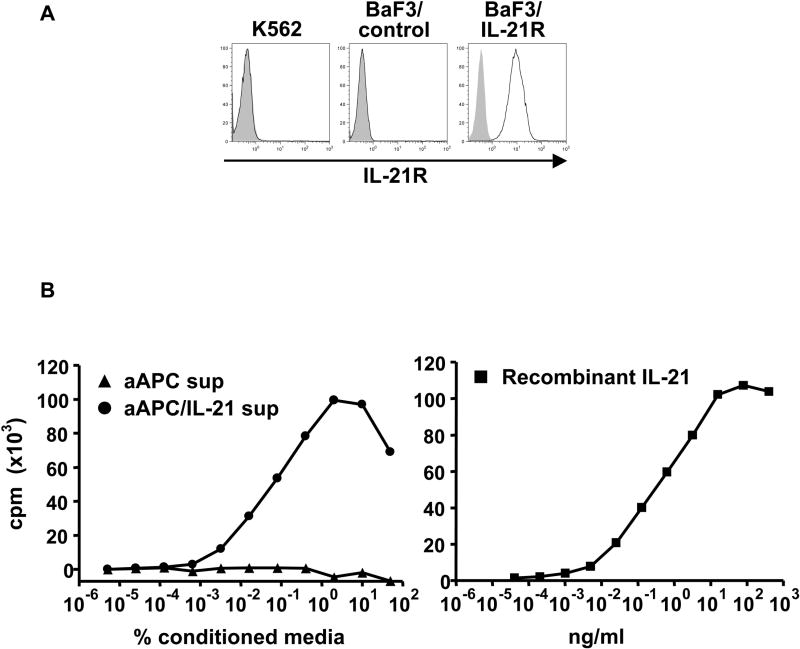

Generation of IL-21R negative aAPC which constitutively secretes IL-21

Using IL-21R positive APC such as DC, others have reported that IL-21 can enhance the generation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with potent effector function and higher avidity. Whether IL-21 acts directly on CD8+ T cells or first modulates IL-21R+ APC, which subsequently stimulate CD8+ T cells, has not yet been determined. Therefore, in order to study the immunologic functions of IL-21 on CD8+ T cells, it is mandatory to separate the effects of IL-21 on IL-21R+ APC from its effects on T cells since IL-21 can modulate the function of APC.

Previously, we reported the generation and characterization of a novel artificial APC (aAPC), which expresses HLA-A2, CD80, and CD83(25, 27). We demonstrated that aAPC is able to support the priming and prolonged expansion of peptide-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells with potent effector functions. Using an IL-21R specific antibody, we confirmed that K562, the parental cell line, lacks IL-21R expression (Figure 2A). In contrast, the same antibody specifically recognized BaF3/IL-21R, a BaF3 cell line transduced with human IL-21R. Using IL-21R negative aAPC, we then generated an APC that constitutively secretes IL-21 (aAPC/IL-21) by further transducing aAPC with human IL-21 cDNA. IL-21 transduction did not affect the expression of A2, CD80, nor CD83 previously transduced (data not shown). In order to verify that IL-21 secreted by aAPC/IL-21 is biologically active, we performed a proliferation assay using BaF3/IL-21R cells(17, 30). Graded amounts of supernatant harvested from aAPC/IL-21 were added to BaF3/IL-21R, and proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. As shown in Figure 2B, conditioned medium derived from aAPC/IL-21, but not from parental aAPC, supported the growth of BaF3/IL-21R in a dose dependent manner. Using rIL-21, we were able to determine that 106 aAPC/IL-21 are capable of constitutively secreting IL-21 at 0.8 μg/ml per 24 hours. These results demonstrate that aAPC/IL-21 lacks the functional receptor for IL-21 and constitutively secretes bioactive IL-21, and can serve as a useful APC for dissecting the immunologic effects of IL-21 on CD8+ T cells.

Figure 2. Generation of IL-21R negative aAPC constitutively secreting IL-21.

(A) K562, the parental cell line of aAPC and aAPC/IL-21, lacks the expression of IL-21R. To create an IL-21 dependent cell line, mouse BaF3 cells were engineered to express human IL-21R. Surface expression of IL-21R on wild-type K562, BaF3 transduced with vector (BaF3 control), and BaF3 cells transduced with human IL-21R (BaF3/IL-21R) was determined by flow cytometry with specific antibody (open curves) and isotype control (shaded curves). (B) aAPC/IL-21 but not aAPC constitutively secretes large amounts of biologically active IL-21. Induction of BaF3/IL-21R proliferation by supernatants derived from aAPC and aAPC/IL-21, and rIL-21 was determined using a standard thymidine proliferation assay. Baseline values for proliferation observed in the absence of conditioned medium or rIL-21 were subtracted. Neither supernatant from aAPC nor aAPC/IL-21 was able to support the growth of BaF3/control cells (data not shown).

IL-21 can enrich and expand large numbers of CD8+ T cells

Using IL-21R null aAPC/IL-21, we first examined the immunological effects of IL-21 on the expansion of newly primed antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Purified CD8+ T cells from HLA-A2+ healthy donors were initially primed with MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC. Each week thereafter, cultures were split and stimulated three times with either MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC or aAPC/IL-21. The ratio of the total number of CD8+ T cells generated by aAPC/IL-21 compared to aAPC was increased by an average of 17.8 fold (3.2-31.4, n=4, P=0.03) (data not shown). Stimulation with aAPC/IL-21 consistently generated a higher percentage of MART1 multimer positive CTL, averaging 45.4% (40.4-55.9 %, n=4), which, compared to aAPC, is increased by 31.2-40.9 percentage points (P=0.002, Figure 3A). As a result, stimulation with aAPC/IL-21 yielded an increase of MART1-specific CTL by an average of 79.8 fold (17.0-163.5, n=4, P=0.04) compared to aAPC (Figure 3B). In summary, starting with 6.5-7.8 × 106 purified CD8+ T cells (n=4), we generated a total of 0.14-1.3 × 108 MART1-specific T cells within 4 weeks. These results suggest that exposure to IL-21 during restimulation promotes the robust expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells initially primed in the absence of IL-21.

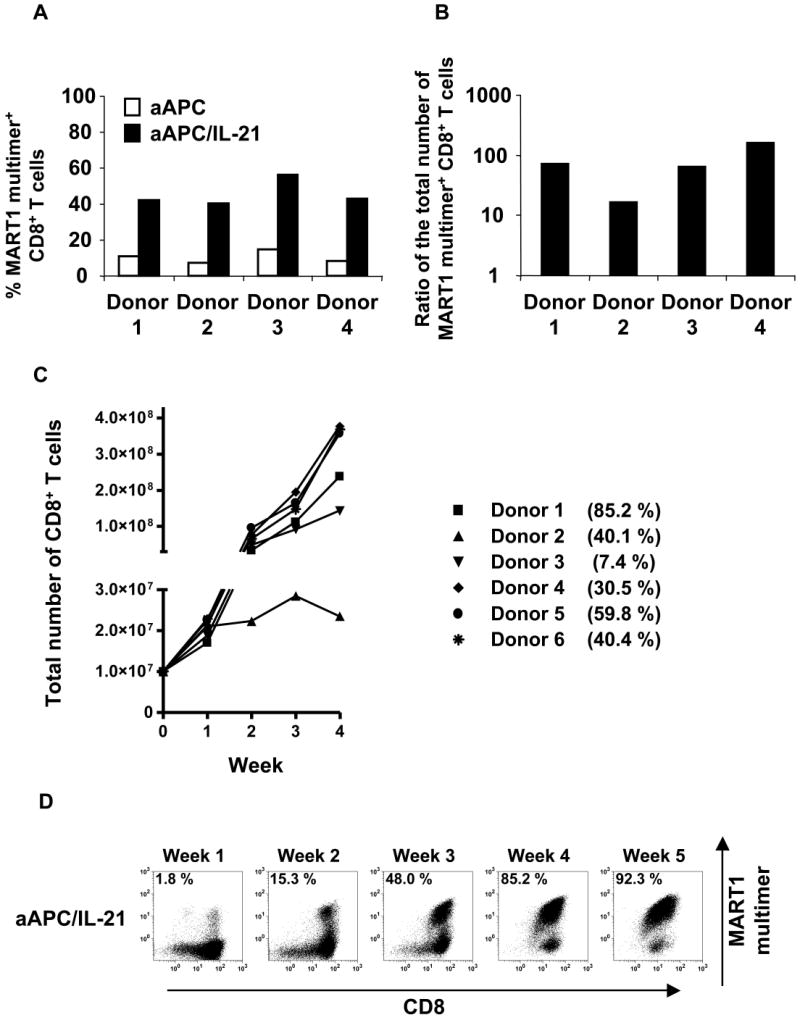

Figure 3. Stimulation in the presence of IL-21 induces robust enrichment and expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

(A) IL-21 augments the expansion and enrichment of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Purified CD8+ T cells from HLA-A2+ healthy donors were primed with aAPC pulsed with MART1 peptide in the absence of IL-21. After one week, T cell cultures were split by half and stimulated three times on a weekly basis with either peptide-pulsed aAPC or aAPC/IL-21. Between stimulations T cells were supplemented with IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml). Resulting T cell cultures were stained with HLA/peptide multimer to determine the percentage of MART1-specific CD8+ T cells. (B) The number of MART1-specific T cells was determined by calculating the product of the total number of T cells and the percentage of multimer positive cells. Shown here is the ratio of the total number of MART1-specific CD8+ T cells generated in the presence versus the absence of IL-21 for each donor. (C) Generation of CTL by both priming and restimulation with MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC/IL-21 was performed. Purified CD8+ T cells from six A2+ healthy donors were stimulated once a week. Between stimulations T cells were supplemented with IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml). The calculated total number of CD8+ T cells generated is shown. The percentage of MART1 multimer positive CD8+ T cells after 4 stimulations is also presented. (D) Representative MART1 multimer staining performed weekly after each stimulation is presented (donor 1 from Figure 3C).

In order to study the maximal effect of IL-21 on the generation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, purified CD8+ T cells from A2+ healthy donors were both primed and restimulated with MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC/IL-21. As shown in Figure 3C, starting with 107 purified CD8+ T cells, we generated 0.23-3.8 × 108 (n=6) CD8+ T cells within 4 weeks, and the mean HLA/peptide multimer positivity was 43.9% (7.4-85.2 %, n=6). MART1 multimer staining after each stimulation for one representative donor is shown in Figure 3D.

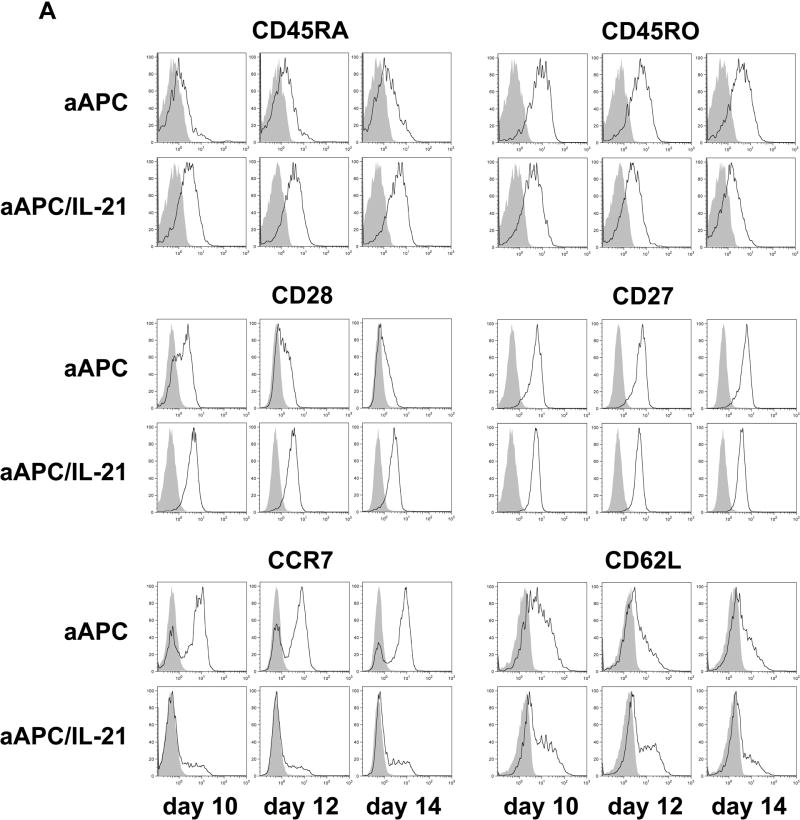

Priming in the presence of IL-21 modulates the phenotype of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells

It has been postulated that critical signaling during priming determines the fate of T cells. Therefore, we studied the effects of exposing CD8+ T cells with IL-21 during priming. Purified CD8+ T cells obtained from A2+ normal donors were stimulated once with either MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC or aAPC/IL-21. Cultures were supplemented with IL-2 and IL-15 every three days without any further stimulation, and phenotypic analysis of MART1 multimer positive T cells was performed 10, 12, and 14 days later. CTL primed with aAPC/IL-21 showed an average of 1.8% multimer positivity (1.0-2.3%, n=3, day 14), which is higher than the average of 1.1% seen in aAPC-primed CTL (0.6-1.4%, n=3, day 14). As published previously(21), priming in the presence of IL-21 resulted in higher expression of CD28 by MART1-specific CTL which might explain the more robust expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells primed with aAPC/IL-21. However, in variance with this report, a higher percentage of MART1-specific CTL generated with aAPC/IL-21 expressed CD45RA and fewer displayed CD45RO (Figure 4A). Both aAPC/IL-21 and aAPC resulted in similarly high CD27 expression by MART1-specific T cells. Compared to aAPC, aAPC/IL-21 generated MART1-specific CTL with a decrease in the percentage of CCR7+ cells, although the effect of IL-21 on the level of CD62L expression was variable. The differential expression of CD28, CD45RA, CD45RO, and CCR7 was consistently observed in all three donors on all three days tested (Figure 4B). Furthermore, using peptide-pulsed aAPC and exogenously added rIL-21 (10-30 ng/ml), we were able to recapitulate these observations, underscoring that these phenotypic alterations are reproducible and specific to IL-21 (data not shown).

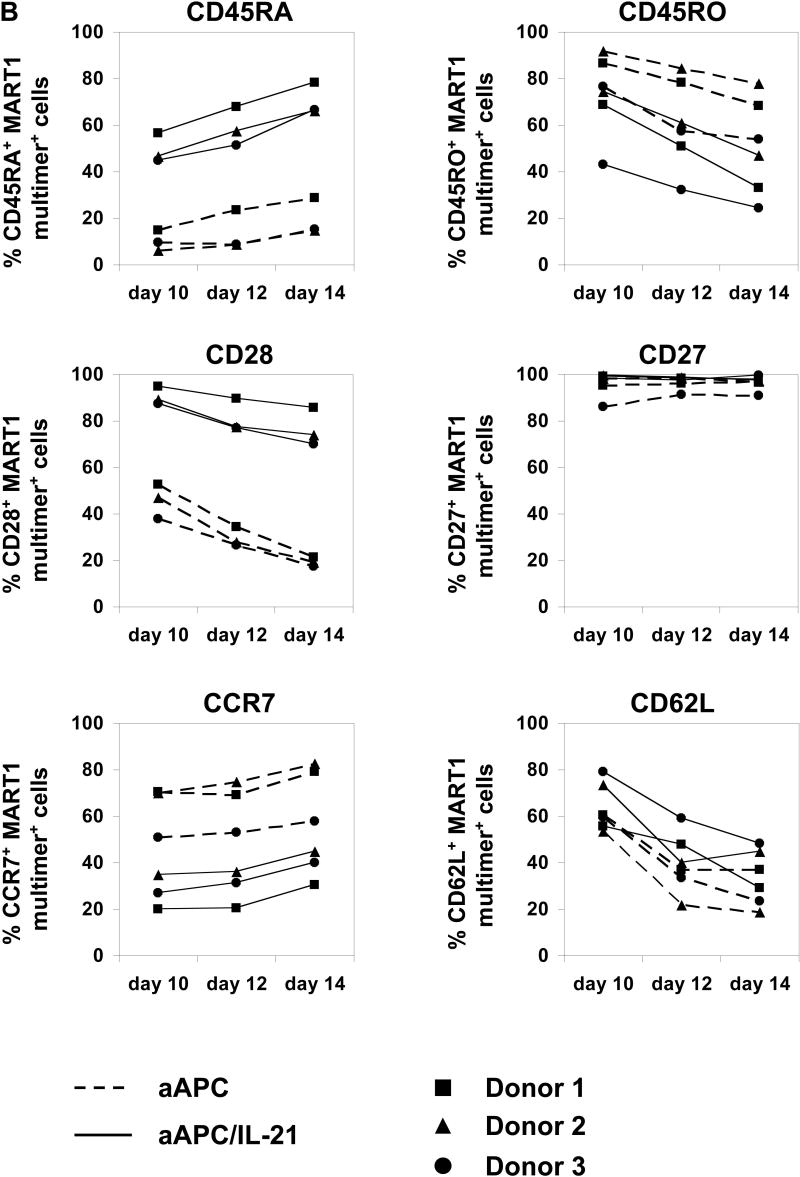

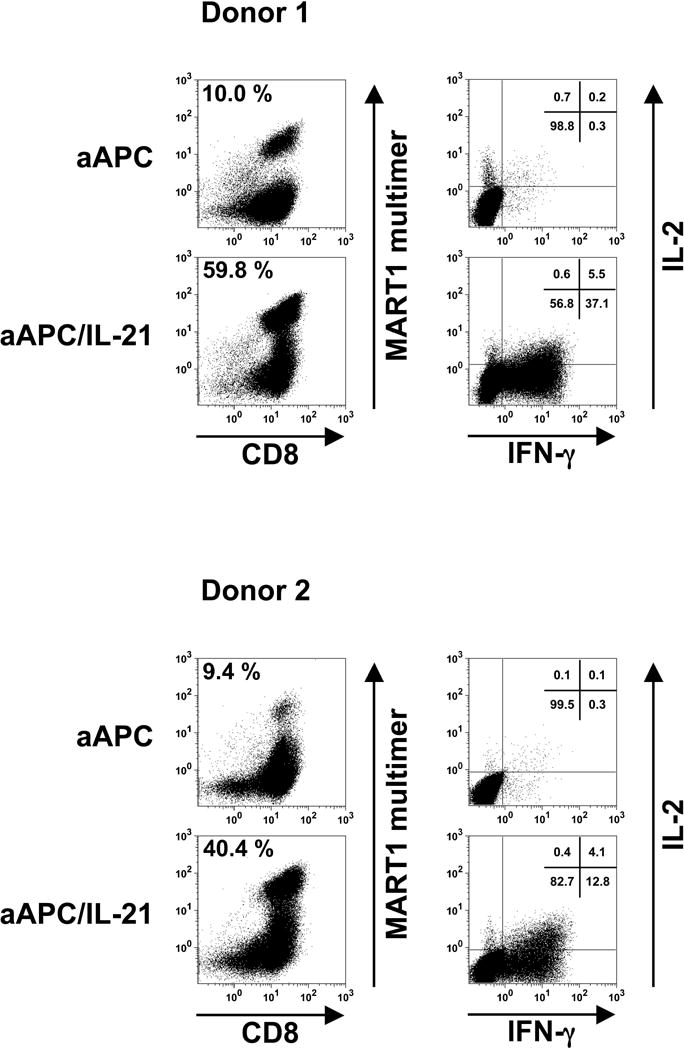

Figure 4. Priming in the presence of IL-21 generates antigen-specific CD8+ T cells with distinct phenotype.

Purified CD8+ T cells from three A2+ healthy donors were primed with either MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC or aAPC/IL-21. Without any restimulation, each culture was supplemented with IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml) every three days. After 10, 12, and 14 days, immunophenotype of MART1–specific T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) A representative result of one donor out of three is presented. Open curves, staining for indicated molecules; shaded curves, isotype controls. Similar results were obtained using aAPC versus aAPC plus rIL-21. (B) A summary of the phenotypic analysis of MART1 multimer positive T cells from all three donors on all three days studied is shown. (C) The effect of chronic stimulation in the presence of IL-21 on the phenotype of antigen-specific T cells was also evaluated. Purified CD8+ T cells from two different healthy donors were stimulated once a week with either MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC or aAPC/IL-21. Between stimulations T cells were supplemented with IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml). After three and five stimulations, MART1 multimer positive T cells were found to have a similar phenotype. Results after 5 stimulations are shown. Open curves, staining for indicated molecules; shaded curves, isotype controls. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results.

Chronic stimulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells abrogates the phenotypic differences induced by IL-21, resulting in a convergence of the immunophenotype

Although the above results clearly revealed the effect of IL-21 on the priming phase, it is important to investigate the effect of IL-21 in the context of chronic stimulations. Purified CD8+ T cells were repeatedly stimulated with either MART1 peptide-pulsed aAPC or aAPC/IL-21 on a weekly basis and cultures were supplemented with IL-2 and IL-15 between stimulations. After five stimulations, however, no large phenotypic difference was observed, except for a remnant of increased CD45RA positivity on MART1-specific CD8+ T cells chronically stimulated with aAPC/IL-21 (Figure 4C). We previously observed that, in some donors CD28 was retained following stimulation with aAPC(27). Similar results were observed with aAPC/IL-21. This data suggests that chronic stimulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells cancels the phenotypic differences induced by IL-21.

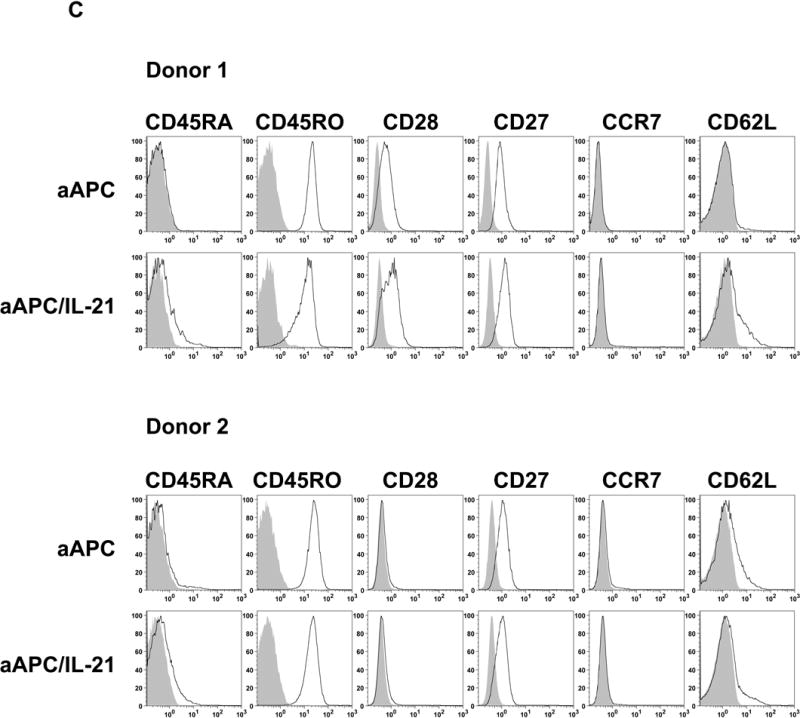

Repeated stimulation in the presence of IL-21 promotes the acquisition of IFN-γ secretion while preserving IL-2 secretion by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells

Chronically stimulated MART1-specific CD8+ T cells were generated as described above. CTL cultures generated in the presence and absence of IL-21 both demonstrated potent antigen-specific cytotoxicity as measured in a standard cytotoxicity assay (data not shown). Large differences between the percentage of multimer positive cells in the two CTL cultures prevent a reliable direct comparison of cytotoxicity on a per antigen-specific CTL basis (See Figure 3A). Therefore, we compared the effector function of generated CTL by measuring peptide-specific intracellular release of IFN-γ and IL-2. As shown in Figure 5, CTL generated in the presence of IL-21 possessed a larger population of cells, which secrete IFN-γ in an antigen-specific manner, suggesting that IL-21 may promote the acquisition of IFN-γ secretion by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, IL-21 treated CTL were also capable of secreting IL-2 in an antigen-specific manner, which may be attributed to the unique function of IL-21, since it has been shown that the ability of IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion is exclusive in the maturation/differentiation ontogeny of CD8+ T cells(31). It should be noted that even after taking into account the higher multimer positivity of IL-21 treated CTL, IL-21 treatment produced MART1 CTL with a higher capacity to secrete IFN-γ on a per cell basis. These results suggest that, although the phenotype of CTL chronically stimulated with aAPC or aAPC/IL-21 was similar, the effector function of these two MART1-specific CD8+ T cells were markedly distinct.

Figure 5. IL-21 promotes the acquisition of IFN-γ secretion while preserving IL-2 secretion by antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Purified CD8+ T cells from A2+ healthy donors were primed and restimulated with either aAPC or aAPC/IL-21 pulsed with MART1 peptide on a weekly basis. Between stimulations T cells were supplemented with IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml). After a total of four stimulations, T cells were analyzed for antigen specificity by HLA/peptide multimer staining and antigen-specific effector function. The panels in the left column depict MART1 multimer staining and the percentages in the upper left corner indicate MART1 multimer+ cells within CD8+ T cells. The panels in the right column show the antigen-specific intracellular release of IL-2 and IFN-γ on gated CD8+ T cells of the corresponding T cell cultures. The percentages of cells present in each quadrant are shown. Results of two different donors out of three are shown.

IL-21 facilitates the generation of anti-tumor CD8+ CTL with low precursor CTL (pCTL) frequency and/or growth potential

Survivin is an inhibitor of apoptosis protein, which is overexpressed in many types of malignant cells and has been shown to be immunogenic in studies both in vivo and in vitro. Therefore, it has been considered to be a promising target for T cell immunotherapy for cancer(32). Although many groups have reported the successful ex vivo generation of survivin-specific human CD8+ T cell lines, the frequency of survivin-specific T cells included in these lines has not always been high indicating a low pCTL frequency and/or growth potential(33-35). In fact, previously reported anti-survivin CTL lines exhibited only modest effector function even at high effector:target (E:T) ratios(33, 34).

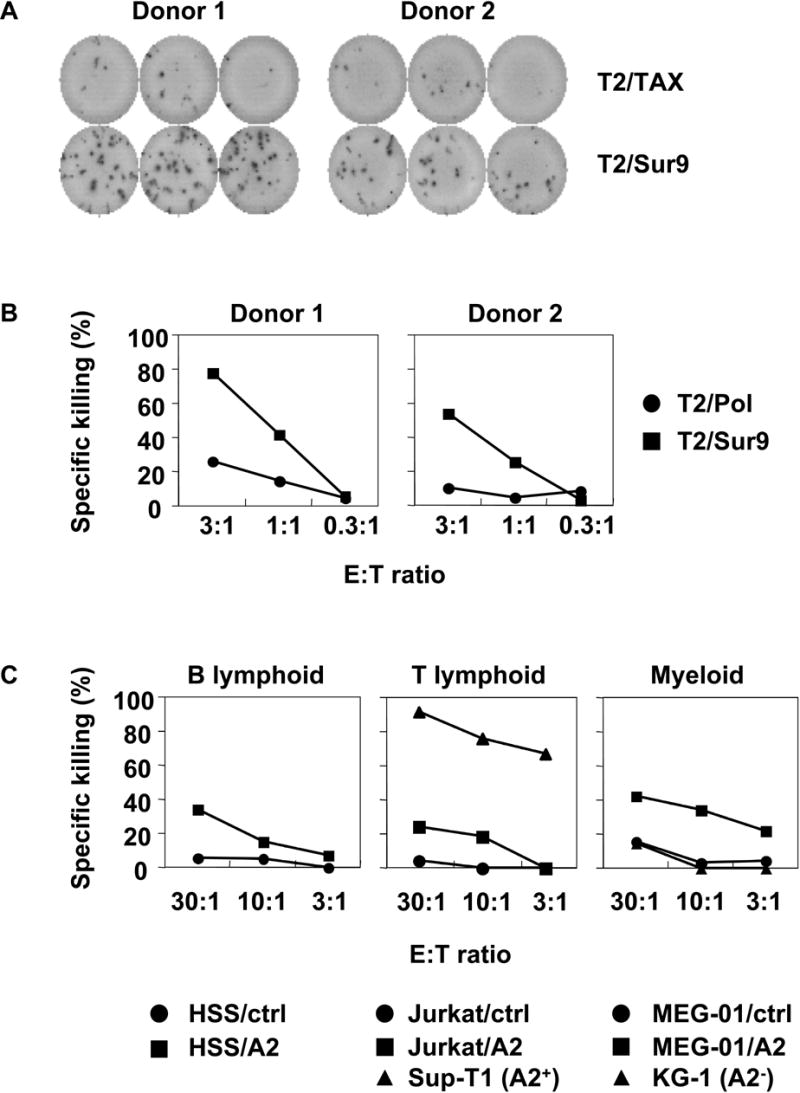

Using survivin as a model antigen with a low pCTL frequency, we attempted to generate survivin-specific CD8+ CTL from two HLA-A2 positive healthy donors using synthetic Sur9 (ELTLGEFLKL) peptide. Purified HLA-A2 positive CD8+ T cells were stimulated with Sur9 peptide-pulsed aAPC/IL-21 at weekly intervals and cultures were supplemented with IL-2 and IL-15 twice a week. Since HLA-A2/Sur9 peptide multimer was not available due to difficulties in the manufacturing process, we employed an IFN-γ ELISPOT to enumerate the frequency of Sur9-specific CD8+ T cells in the culture. After 4 stimulations, as shown in Figure 6A, 72±8 and 36±6 cells per 1,000 cells in donors 1 and 2, respectively, secreted IFN-γ in an antigen-specific manner. Survivin-derived Sur9 peptide-specific CTL specifically cytolyzed T2 cells pulsed with Sur9 peptide but not T2 cells pulsed with the control peptide, Pol, at an E:T ratio as low as 1:1 (Figure 6B). In order to demonstrate that the Sur9-specific CTL lines generated have high functional TCR avidity, standard cytotoxicity of hematologic cancer cells from different lineages was tested (Figure 6C). HLA-A2 positive and HLA-A2 transduced Survivin+ cancer cells but not HLA-A2 negative or mock transduced Survivin+ cells were recognized by the CTL at E:T ratios as low as 3:1. These results indicate that IL-21 may facilitate the generation of anti-tumor CD8+ CTL with low pCTL frequency and/or growth potential.

Figure 6. IL-21 can enhance the generation of anti-tumor CD8+ T cells with low pCTL frequency and/or growth potential.

Survivin-specific CTL were generated using aAPC/IL-21. Purified CD8+ T cells from A2+ healthy donors were stimulated on a weekly basis with aAPC/IL-21 pulsed with Sur9 peptide. Between stimulations T cells were supplemented with IL-2 (10 IU/ml) and IL-15 (10 ng/ml). After 4 stimulations, survivin-specific effector functions were evaluated by IFN-γ ELISPOT and standard 51Cr release assay. (A) Survivin-specific IFN-γ secretion was studied by IFN-γ ELISPOT. CD8+ T cells were incubated with T2 cells pulsed with either Sur9 or HTLV-I-derived TAX control peptide. (B) Cytotoxicity assay was performed using radiolabeled T2 cells pulsed with Sur9 peptide (■) or HIV-derived Pol peptide (●). (C) Sur9 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells generated by aAPC/IL-21 possessed high TCR avidity and recognized hematologic tumor cells in an HLA-A2-restricted manner. Cytotoxicity assay was performed using radiolabeled hematologic cancer cells from different lineages. HLA-A2 negative cell lines were engineered to express HLA-A2 as previously described(26). The cell lines used as targets were HSS (HS-Sultan, myeloma cell line); Sup-T1 (T lymphoblastic lymphoma cell line); Jurkat (T cell leukemia cell line), MEG-01 (megakaryoblastic cell line); and KG-1 (acute myelogenous leukemia cell line).

Discussion

Functional IL-21R is expressed by most immune cells such as B cells, T cells, NK cells and DC. The requirement of the unique IL-21R chain for signal transduction suggests that IL-21 may possess novel immunologic functions(18-20). In vivo studies using IL-21 and IL-21R null mice demonstrated that IL-21:IL-21R signaling critically regulates the proliferation and function of T, B, and NK cells(22, 23, 36). In these studies, however, the specific functional role of IL-21 and IL-21R on DC has not been fully illuminated. Murine studies in vitro have previously shown that IL-21 inhibits the upregulation of class II, CD80 and CD86 expression by DC in response to maturation signals(24). Our study confirms and extends these results since we have shown for the first time in humans that IL-21 has a similar immunoinhibitory effect on human DC immunogenicity and expression of costimulatory molecules. However, our results also suggest that the IL-21 effect on human DC is more selective than in the mouse given the preserved expression of HLA-DR.

A number of reports have been published that IL-21 can enhance the generation of highly avid CD8+ T cells with potent effector function(21, 23, 37, 38). However, IL-21R is constitutively and widely expressed on most APC such as DC, B cells, monocytes and macrophages which are commonly used for stimulation of responder T cells. Therefore, it has remained elusive whether IL-21 acts directly on responding CD8+ T cells or by enhancing the stimulatory effects of APC. To address this controversy, we generated a novel IL-21R negative aAPC that constitutively secretes IL-21 and tested whether IL-21 can act directly on antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Since aAPC and aAPC/IL-21 lack the expression of IL-21R, it is highly unlikely that IL-21 modulates the immunogenicity of these APC through delivery of signals in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. Using an experimental system comprised of only two cell components, i.e. aAPC/IL-21 and purified CD8+ T cells, we have unequivocally demonstrated that IL-21 directly delivers its stimulatory signal to antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. We have also demonstrated that IL-21 during priming mediates consistent phenotypic changes during CD8+ T cell maturation and differentiation. Findings in variance with previously published reports on the phenotype of T cells generated using IL-21 are likely due to the impact of IL-21 on cocultured IL-21R positive APC which are absent in our cultures. Moreover, aAPC/IL-21 enabled the expansion of anti-tumor CTL with low pCTL frequency. Since IL-2 and IL-15 are included as a default in our T cell culture, it is clear that the observed effects are unique to IL-21 secreted from aAPC/IL-21 and cannot be replaced by IL-2 and/or IL-15. The fact that rIL-21 can be used with aAPC to recapitulate the presented immunologic functions of aAPC/IL-21 further corroborates our findings (data not shown).

There are at least two proposed models that explain the molecular mechanisms of CD4+ T cell help for CD8+ T cells. The first model suggests that helper CD4+ T cells and CD8+ CTL recognize their cognate antigens simultaneously on the same APC and that cytokines produced by the activated helper CD4+ T cells act in a paracrine fashion to facilitate the CD8+ CTL response(39, 40). Alternatively, it has been suggested that DC are activated, or “licensed,” by interacting with antigen-specific CD4+ helper T cells through CD40-CD40L interactions resulting in the ability of activated DC to prime antigen-specific CD8+ T cells(41-43). IL-21 is located at a unique position in the generation of antigen-specific cellular responses since IL-21 is predominantly secreted by activated CD4+ T cells and since IL-21 possesses opposing effects on DC and CD8+ T cells. While CD4+ T cells may “license” DC through CD40 ligation, they can also limit this activation through IL-21 secretion. On the other hand, however, CD4+ T cells may directly provide “help” to primed CD8+ T cells through secretion of IL-21, as well as IL-2 and IL-15. Thus, IL-21 can control CD8+ T cell responses by positively regulating CD8+ T cells but also simultaneously limiting this response through negative regulation of DC.

By circumventing the immunosuppressive effects of IL-21, our IL-21R deficient aAPC might serve as a unique platform to generate large numbers of tumor-specific CTL. We have previously shown that these T cells can be maintained in vitro for remarkably long periods of time, up to 1.5 years in some cases. Also, as shown in Figure 4B and 4C, CD8+ CTL generated with our IL-21R negative aAPC express consistently high levels of CD27. Studies conducted with ex vivo expanded tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) samples that were administered to melanoma patients have indicated that transferred T cells which persist for 2 months display an effector memory phenotype with a CD27+ CD28+ CD62L− CCR7− profile(44). The size of the pool of CD27+ CD8+ T cells in bulk TIL was highly associated with the ability of these TIL to mediate tumor regression following adoptive transfer(45). We have successfully produced a clinical grade aAPC, aAPC33, and are embarking on a “first into human” clinical trial where advanced melanoma patients will be infused with autologous MART1-specific CD8+ CTL. It would be intriguing to compare CTL lines generated in the presence or absence of IL-21 in regards to their ability to persist and home to tumor sites, since IL-21 upregulates the expression of CD28 and downregulates CCR7 expression as shown in Figure 4A and 4B.

The biologic activity of IL-21 on CTL and NK cells led to the testing of this cytokine in clinical trials in metastatic melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma either alone or in combination with other approved drugs. It has been reported that IL-21 administration to humans is reasonably well tolerated and has demonstrated preliminary evidence of anti-tumor activity in patients with melanoma and renal cancer(46, 47). However, our results clearly suggest that IL-21 administration may result in unexpected immunosuppressive effects by inhibiting the maturation of DC, which is critical for the optimal priming of naïve T cells and the generation of anti-tumor effector T cells. Even after priming, IL-21 exposure may result in the generation of DC with impaired maturity which may anergize or tolerize existing effector T cells and attenuate their anti-tumor response. However, we also clearly demonstrate that IL-21 can unequivocally enhance the expansion of CTL with potent effector function. Strategic use of IL-21, therefore, could be a powerful tool for enhancing immune responses. Therefore, it is imperative that the use of IL-21 in the clinic is guided by these underlying principles, and that treatment strategies are designed which exploit these dichotomous effects to therapeutic advantage.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Supported by the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung der Deutschen Krebshilfe (S. Ansén), NIH grants CA87720 (M.O. Butler), CA92625 (L.M. Nadler), HL54785 (N. Hirano) and CA129240 (N. Hirano), and grant from the Cancer Research Institute (L.M. Nadler).

We thank J. Griffin for providing us with BaF3 and WEHI-3B cells.

Footnotes

Statement of Clinical Relevance

The immunostimulatory effects of IL-21 on effector immune cells such as T cells and NK cells have been well documented in both in vivo and in vitro studies. As a result, IL-21 has been tested in clinical trials for cancer in the hope that anti-tumor immunity would be enhanced. Unfortunately, although the administration of biologically active doses of IL-21 appears to be safe, only limited clinical benefit has been reported. In this paper, we provide a comprehensive analysis of IL-21's opposing actions on human dendritic cells and CD8+ T cells. We also demonstrate that the use of IL-21 can provide large benefit for the ex vivo culture and expansion of tumor antigen specific cytotoxic T cells when an IL-21R negative antigen-presenting cell (APC) is used as a stimulator. Our results may be of help in designing future clinical trials involving IL-21 in order to harness its stimulatory effects on T cells while mitigating its suppressive immunologic effects on APC (159 words).

References

- 1.Gattinoni L, Powell DJ, Jr, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nature reviews. 2006;6:383–93. doi: 10.1038/nri1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leen AM, Rooney CM, Foster AE. Improving T cell therapy for cancer. Annual review of immunology. 2007;25:243–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.June CH. Principles of adoptive T cell cancer therapy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1204–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI31446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nature reviews. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Melief CJ. Dendritic cell immunotherapy: mapping the way. Nature medicine. 2004;10:475–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JV, Latouche JB, Riviere I, Sadelain M. The ABCs of artificial antigen presentation. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:403–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultze JL, Grabbe S, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS. DCs and CD40-activated B cells: current and future avenues to cellular cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:659–64. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Cytokine control of memory T-cell development and survival. Nature reviews. 2003;3:269–79. doi: 10.1038/nri1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkins MB. Cytokine-based therapy and biochemotherapy for advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2353s–8s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antony PA, Restifo NP. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells, immunotherapy of cancer, and interleukin-2. J Immunother. 2005;28:120–8. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000155049.26787.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wan YY, Flavell RA. The roles for cytokines in the generation and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunological reviews. 2006;212:114–30. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma A, Koka R, Burkett P. Diverse functions of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-7 in lymphoid homeostasis. Annual review of immunology. 2006;24:657–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surh CD, Boyman O, Purton JF, Sprent J. Homeostasis of memory T cells. Immunological reviews. 2006;211:154–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg SA, Sportes C, Ahmadzadeh M, et al. IL-7 administration to humans leads to expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ cells but a relative decrease of CD4+ T-regulatory cells. J Immunother. 2006;29:313–9. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000210386.55951.c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nature reviews. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, et al. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:9571–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503726102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parrish-Novak J, Dillon SR, Nelson A, et al. Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature. 2000;408:57–63. doi: 10.1038/35040504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonard WJ, Spolski R. Interleukin-21: a modulator of lymphoid proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. Nature reviews. 2005;5:688–98. doi: 10.1038/nri1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis ID, Skak K, Smyth MJ, Kristjansen PE, Miller DM, Sivakumar PV. Interleukin-21 signaling: functions in cancer and autoimmunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6926–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spolski R, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-21: Basic Biology and Implications for Cancer and Autoimmunity. Annual review of immunology. 2007 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Bleakley M, Yee C. IL-21 influences the frequency, phenotype, and affinity of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response. J Immunol. 2005;175:2261–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasaian MT, Whitters MJ, Carter LL, et al. IL-21 limits NK cell responses and promotes antigen-specific T cell activation: a mediator of the transition from innate to adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2002;16:559–69. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng R, Spolski R, Finkelstein SE, et al. Synergy of IL-21 and IL-15 in regulating CD8+ T cell expansion and function. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;201:139–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt K, Bulfone-Paus S, Foster DC, Ruckert R. Interleukin-21 inhibits dendritic cell activation and maturation. Blood. 2003;102:4090–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano N, Butler MO, Xia Z, et al. Identification of an immunogenic CD8+ T-cell epitope derived from gamma-globin, a putative tumor-associated antigen for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2662–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirano N, Butler MO, Xia Z, et al. Engagement of CD83 ligand induces prolonged expansion of CD8+ T cells and preferential enrichment for antigen specificity. Blood. 2006;107:1528–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler MO, Lee JS, Ansen S, et al. Long-lived antitumor CD8+ lymphocytes for adoptive therapy generated using an artificial antigen-presenting cell. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1857–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirano N, Butler MO, Xia Z, et al. Efficient presentation of naturally processed HLA class I peptides by artificial antigen-presenting cells for the generation of effective antitumor responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2967–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spisek R, Bretaudeau L, Barbieux I, Meflah K, Gregoire M. Standardized generation of fully mature p70 IL-12 secreting monocyte-derived dendritic cells for clinical use. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:417–27. doi: 10.1007/s002620100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habib T, Senadheera S, Weinberg K, Kaushansky K. The common gamma chain (gamma c) is a required signaling component of the IL-21 receptor and supports IL-21-induced cell proliferation via JAK3. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8725–31. doi: 10.1021/bi0202023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. CD8+ T-cell memory in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Immunological reviews. 2006;211:214–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed JC, Wilson DB. Cancer immunotherapy targeting survivin: commentary re: V. Pisarev et al., full-length dominant-negative survivin for cancer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res., 9:6523-6533, 2003. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6310–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casati C, Dalerba P, Rivoltini L, et al. The apoptosis inhibitor protein survivin induces tumor-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer research. 2003;63:4507–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisarev V, Yu B, Salup R, Sherman S, Altieri DC, Gabrilovich DI. Full-length dominant-negative survivin for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6523–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt SM, Schag K, Muller MR, et al. Survivin is a shared tumor-associated antigen expressed in a broad variety of malignancies and recognized by specific cytotoxic T cells. Blood. 2003;102:571–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Feng CG, et al. Science. Vol. 298. (New York, NY: 2002. A critical role for IL-21 in regulating immunoglobulin production; pp. 1630–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moroz A, Eppolito C, Li Q, Tao J, Clegg CH, Shrikant PA. IL-21 enhances and sustains CD8+ T cell responses to achieve durable tumor immunity: comparative evaluation of IL-2, IL-15, and IL-21. J Immunol. 2004;173:900–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Leeuwen EM, van Buul JD, Remmerswaal EB, Hordijk PL, ten Berge IJ, van Lier RA. Functional re-expression of CCR7 on CMV-specific CD8+ T cells upon antigenic stimulation. International immunology. 2005;17:713–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keene JA, Forman J. Helper activity is required for the in vivo generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1982;155:768–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.3.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchison NA, O'Malley C. Three-cell-type clusters of T cells with antigen-presenting cells best explain the epitope linkage and noncognate requirements of the in vivo cytolytic response. European journal of immunology. 1987;17:1579–83. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–80. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–8. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–3. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell DJ, Jr, Dudley ME, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA. Transition of late-stage effector T cells to CD27+ CD28+ tumor-reactive effector memory T cells in humans after adoptive cell transfer therapy. Blood. 2005;105:241–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, Kerstann KW, Ahmadzadeh M, et al. Modulation by IL-2 of CD70 and CD27 expression on CD8+ T cells: importance for the therapeutic effectiveness of cell transfer immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2006;176:7726–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curti BD. Immunomodulatory and antitumor effects of interleukin-21 in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2006;6:905–9. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.6.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis ID, Skrumsager BK, Cebon J, et al. An open-label, two-arm, phase I trial of recombinant human interleukin-21 in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3630–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]