In 1981, researchers working independently on two continents ushered in a new era of biomedicine by isolating stem cells from early mouse embryos and sustaining the famously finicky cells in Petri dishes. These cultured “pluripotent” cells, which can generate any of the 200-plus cell types in the body, looked and behaved like normal embryo cells, giving researchers a powerful model for understanding development and disease. But efforts to develop similar tools working with human embryonic stem (ES) cells stalled when ethical and legal restrictions on human embryos and embryonic cell lines hamstrung a field still in its infancy.

The future looked brighter in 2007, when teams of scientists, again working independently, reported a way to produce human ES cells without eggs. The technique, demonstrated in mice in 2006, reset the developmental clock of adult human skin cells back into an embryonic state, freed of their epithelial obligations and receptive to an entirely different fate. Infecting human skin cells (or mouse embryonic fibroblasts, MEFs, in the 2006 study) with retroviral vectors carrying four reprogramming genes—Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc—generated induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells that appear indistinguishable from ES cells in terms of morphology, cell surface markers, proliferative capacity, gene expression, and methylation state. (Stem cells have different “epigenetic” modifications such as methylation, the addition of methyl groups to DNA, than differentiated cells do, allowing them to keep their developmental options open.) Only about 0.01% of the adult cells became iPS cells, however, and the origin of these cells was unknown.

Now, Jose Silva, Austin Smith, and colleagues report that iPS cells can be generated faster and more efficiently by genetically reprogramming stem cells derived from tissue. The researchers suspected that tissue-derived stem cells might have fewer epigenetic restrictions and thus respond better to reprogramming signals than other cells. Previous work showed that neural stem (NS) cells can be efficiently converted into pluripotent cells using two common reprogramming techniques (fusion with ES cells and transfer of nuclear material into eggs cells). The researchers wondered whether NS cells extracted from mouse brains would respond similarly to iPS.

To reprogram body (somatic) cells into iPS cells, researchers first isolate and culture cells, then use a retrovirus to introduce the reprogramming genes into the cells. Typically, reprogramming involves repeating this step several times to yield rare cells that undergo reprogramming through apparently random processes. Silva et al. hoped that by using tissue-derived cells and identifying optimal conditions for reprogramming, they could generate far more iPS cells in less time.

First, they infected MEFs with retroviral vectors carrying the reprogramming factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc, following the protocol described in the 2006 study. Consistent with previous reports, the cells reached an undifferentiated state after three weeks, based on appearance and expression of an Oct4 reporter transgene, which appears as the cell takes over Oct4 expression from the retrovirus. When the researchers infected NS cells with the reprogramming vectors, they found a surprisingly high percentage had acquired the characteristic appearance and surface markers of ES cells (Fgf4, Rex1, Nanog, and endogenous Oct4), though at lower levels. The converted cells did not qualify as pluripotent, however, because their X chromosomes remained inactive. (In differentiated cells, epigenetic marks silence one X chromosome in female cells, so females don't produce twice as many X-linked gene products as males.).

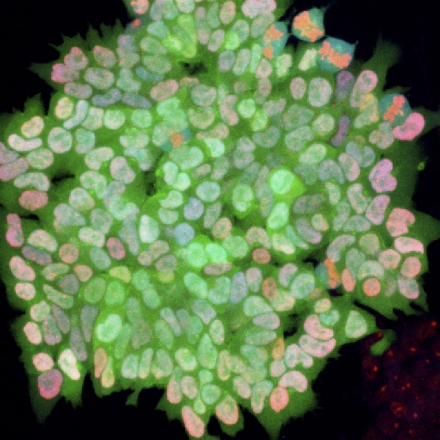

The pluripotency of ES cells can be maintained indefinitely by using a chemical cocktail designed to inhibit differentiation signals. The researchers wondered whether these conditions could jumpstart the resetting process in the partially reprogrammed cells. They used a culture medium spiked with two small molecule inhibitors (2i) and bathed the cells with a factor (LIF) known to maximize ES cell self-renewal. Treated MEF cells yielded far fewer undifferentiated colonies than the NS cells, which passed all the tests of pluripotency: appropriate levels of ES cell marker expression; silencing of retroviral transgenes; gene expression from both X chromosomes; and the gold standard, healthy chimeric mice. Injecting 2i-iPS cells into mouse blastocysts generated live mice, indicating that the iPS cells had acted like normal ES cells to produce all the cell types that form a mouse, including the germ cells.

Silva et al. go on to show that their 2i cocktail induced transition to pluripotency, rather than selecting rare cells that had already reached that state by chance. Furthermore, NS cells could reach pluripotency with just two of the reprogramming factors, Oct4 and Klf4, though with less efficiency.

This reprogramming approach produces cells in an undifferentiated but not pluripotent “pre-iPS” state—“poised on the threshold of pluripotency”—that can be stably maintained and propagated, then rapidly converted to pluripotency with a 2i/LIF elixir. This recipe may provide a final push by imposing what the researchers call a “ground state,” in which cells exist free of differentiation and epigenetic restrictions while retaining the ability to self-renew indefinitely. Because this technique requires fewer viral integrations, it may reduce the risk of cancer-promoting transgene integrations, a concern for using human iPS cells in regenerative medicine. And because it can yield abundant colonies of iPS cells with relative speed, it offers embattled stem cell researchers a flexible new technique for understanding one of biology's most enduring mysteries: how pluripotent cells maintain the delicate balance between differentiation and immortality.