Abstract

A comprehensive model has yet to emerge, but it seems likely that numerous mechanisms contribute to the specificity of olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) axon innervation of the olfactory bulb. Elsewhere in the nervous system the Wnt/Fz family has been implicated in patterning of anterior-posterior axes, cell type specification, cell proliferation and axon guidance. Because of our work describing cadherin-catenin family member expression in the primary olfactory pathway, and because mechanisms of Wnt-Fz interactions can depend in part on catenins, we were encouraged to explore Wnt-Fz expression and function in OSN axon extension. Here, we show that OSNs express Fz-1, -3, and Wnt-5a, while olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs) express Wnt-4. Fz-7 is also expressed in the olfactory nerve by cells that delineate large axon fascicles, but are negative for OEC markers. Fz-1 showed a developmental down-regulation. However, in adults it is expressed at different levels across the olfactory epithelium and in restricted glomeruli across the olfactory bulb, suggesting an important role in the formation and maintenance of OSN connections to the olfactory bulb. Reporter TOPGAL mice demonstrated that some OECs located in the inner olfactory nerve layer can respond to Wnt ligands. Of further interest, we show here with in vitro assays that Wnt-5a increases OSN axon outgrowth and alters growth cone morphology. Our data point to a key role for Wnt/Fz molecules in the development of the mouse olfactory system, providing complementary mechanisms required for OSN axon extension and coalescence.

Keywords: Olfactory Epithelium, Olfactory Bulb, Glomeruli, Olfactory Ensheathing Cell, Olfactory Pathway, Growth Cones

Introduction

Axon guidance in the olfactory system presents several challenges: 1) there are multiple olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) subpopulations in the olfactory epithelium (OE), each of which expresses only 1 of ~1100 different odorant receptors (ORs) (Chess et al., 1994; Serizawa et al., 2003); 2) OSN axons remain heterogeneously fasciculated until proximal to specific olfactory bulb (OB) glomeruli (Miyamichi et al., 2005; Ressler et al., 1993); and 3) all OSN axons expressing the same OR converge into 1–2 glomeruli, and all axons innervating any one glomerulus express the same OR (Mombaerts, 2006; Treloar et al., 2002).

What mechanisms underlie the specificity of OSN axon guidance? Evidence for a direct role of ORs, beyond any influence via odor-induced activity, is unequivocal (e.g.(Feinstein and Mombaerts, 2004; Mombaerts et al., 1996). Recent attention has also focused on the role of G protein-regulated adenylyl cyclase activity and cAMP formation on OSN axon coalescence and targeting (Chesler et al., 2007; Col et al., 2007; Imai et al., 2006; Zou et al., 2007). Nonetheless, neither ORs nor their downstream effectors appear sufficient to fully account for axon targeting (Mombaerts, 2006)for review). Other candidates include ephrins/Ephs (Cutforth et al., 2003; St John et al., 2002), semaphorins/neuropilins (Williams-Hogarth et al., 2000), robos/slits (Marillat et al., 2002), netrins/DCC (Astic et al., 2002), cell surface glycoconjugates (Lipscomb et al., 2003; St John et al., 2006) and recently Kirrel-2 and -3 which may also be regulated by neuronal activity (Serizawa et al., 2006). Despite recent progress, a comprehensive model of specificity in OSN axon guidance remains elusive.

Mammalian homologues of Drosophila wingless gene (Wingless-Int (Wnt)) broadly influence development (e.g. (Croce and McClay, 2006; Guder et al., 2006). The Wnts, cysteine-rich secreted glycoproteins, influence cell proliferation (Vincan et al., 2007), migration (Tam et al., 2006), polarity (Wang et al., 2006a), axon guidance (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003) and synapse formation/stabilization (Salinas, 2005). Wnt molecules bind Frizzled (Fz) proteins, seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors. The canonical β-catenin pathway includes Wnt binding to Fz which stabilizes β-catenin directing gene expression. β-catenin can also interact with the cytoplasmic domain of cadherin proteins (Weis and Nelson, 2006) and play a role in adherens junction formation (Akins and Greer, 2006a).

Evidence of Wnt-Fz regulated axon guidance elsewhere in the nervous system (Keeble et al., 2006; Lyuksyutova et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2002), coupled with our recent demonstration of cadherin-catenin expression in the primary olfactory pathway (Akins et al., 2007; Akins and Greer, 2006a; Akins and Greer, 2006b), encouraged us to explore Wnt-Fz expression and function in OSN axon extension. Our data show localization of Wnt-4 and -5a in the primary olfactory pathway and a spatio-temporal gradient of Fz-1 and -3, consistent with a role in OSN axon guidance. Our in vitro assays demonstrate that Wnt-5a regulates OSN axon outgrowth and growth cone morphology. These data point to a pivotal involvement of the Wnt-Fz family in the development of the mouse olfactory system and provide further diversity for the complex mechanisms required for OSN axon extension and coalescence.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Pregnant, time-mated CD-1 mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) and the TOPGAL reporter mice on a CD-1 background (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg, i.p.; Nembutal; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) prior to cesarean section. The embryos were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS: 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) and 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4] at 4°C overnight. Embryos were collected at embryonic days (E) E9, 9.5, 10, 10.5, 11, 13 and 17 where the day of conception is designated as E0. Postnatal (P) mice at P4 were rapidly decapitated and immersion fixed in 4% PFA in PBS at 4°C overnight. For P21 and adult tissue, CD-1 and TOPGAL mice were anesthetized with 80 mg/kg Nembutal and intracardiacally perfused with 4% PFA in PBS, pH 7.4. The heads were dissected, immersed in fixative for 2 h at 4°C, rinsed in PBS and decalcified in saturated ethylene-diamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA) on a shaker at 4°C for a 1 week. All bones and teeth were removed before further processing. All procedures undertaken in this study were approved by Yale University’s Animal Care and Use Committee and conform to NIH guidelines.

Sectioning

Tissue was cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C until the tissue sank and then was frozen in O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Olfactory tissue was then serially sectioned (20 μm thick) using a Reichert-Jung 2800 Frigocut E cryostat. Sections were thaw mounted onto SuperFrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), air-dried, and stored at −20°C until needed.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were immunostained with antibodies as described below. Briefly, tissue was thawed, air dried and when needed processed for antigen retrieval protocol by steaming for 10 min in 0.01 M sodium citrate. The tissue was then incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS-T (PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, Sigma) for 30 min to block nonspecific binding sites. Incubation with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer was performed overnight at room temperature (RT). Sections were then washed 3 times in PBS-T for 5 min and incubated in secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluors (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted 1:1,000 in blocking buffer for 1 h at RT. Sections were washed (as above), rinsed in PBS, mounted in Gel/Mount mounting medium (Biomeda, Foster City, CA), and coverslipped.

Images were acquired with a Leica confocal microscope, using 40X or 63X oil-immersion objectives. Z-stacks images were acquired at 0.5μm steps. Images displayed are maximum projections, generated with Leica confocal software. Digital images were color balanced using Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). The composition of the images was not altered in any way. Plates were constructed using Corel Draw 12.0 (Corel, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Antibody Characterization

Goat anti Fz-1 (immunogen: purified NS0-derived, recombinant mouse Frizzled-1 extracellular Cysteine-Rich Domain, cat# AF1120, dilution 1/200), goat anti Fz-3 (immunogen: purified NS0-derived, recombinant mouse Frizzled-3 extracellular CRD, cat# AF1001, dilution 1/100) and goat anti Fz-7 (immunogen: purified NS0-derived, recombinant mouse Frizzled-7 (amino acids 33 – 185), cat# AF198, dilution 1/100) were obtained from R&D Systems. The Cysteine Rich Domain encompasses amino acids 50–171 on Fz-1 protein and amino acids 34–158 on Fz-3 protein. As previously described for various Fz receptors, and for these three in particular (Carron et al., 2003; Kaykas et al., 2004; Struewing et al., 2007), Western blot analysis from P4 OE with these three antibodies showed the expected multiple bands: > 200kDa (oligomers); ~140 kDa (dimmers), and isoforms of ~65–75 kDa, corresponding to the monomers with different degrees of glycosylation. The higher molecular weight bands could be reduced by increasing the concentration of the reducing agent (DTT).

Goat anti Wnt-4 (immunogen: recombinant mouse Wnt-4 peptide consisting of amino acid residues 37 – 76 and 222 – 295, cat# AF475, dilution 1/50), goat anti Wnt-5a (immunogen: recombinant mouse Wnt-5a peptide containing amino acid residues Gln 254 - Cys 334, cat# AF645, dilution 1/50) and goat anti Wnt-11 (immunogen: recombinant peptide containing Wnt-11 amino acid residues 37 – 79 and 225 – 297, cat# AF2647, dilution 1/100) were obtained from R&D Systems. Western blot analysis from P4 OE with these three antibodies showed one single band of the expected molecular weight. Wnt-4, -5a and 11 require an antigen retrieval protocol in order to be detected by their respective antibodies.

Chicken anti OMP was a generous gift from Dr. Qizhi Gong (immunogen: purified bacterial GST conjugated OMP protein, full length, dilution 1/4000). OE sections double stained with goat anti OMP (Wako, Cat# 544-10001) and this antibody showed exactly the same pattern. Rabbit anti GAP-43 (immunogen: synthetic peptide corresponding to amino acids 216–226 of rat/mouse GAP-43; Novus Biological, cat# NB300-143; dilution: 1:1000). The staining pattern was as previously described (Iwema and Schwob, 2003), staining OSNs located in the lower part of the OE. Rabbit anti ACIII antibody (immunogen: synthetic peptide representing the C-terminal 20 amino acids of mouse ACIII - PAAFPNGSSVTLPHQVVDNP; Santa Cruz, cat# sc-588; dilution 1/200) stained the OSN cilia in the surface of the OE as it was previously described (Treloar et al., 2005). Rabbit anti NCAM antibody (immunogen: highly purified chicken NCAM; Chemicon, cat# AB5032, dilution 1/1000) showed the expected pattern both in the OE and in OSN cultured cells (Whitesides and LaMantia, 1996).

Rabbit anti Brain Lipid Binding Protein (BLBP) antibody (immunogen: recombinant whole BLBP; Chemicon, cat# AB9558; 1/2000) labeled olfactory ensheathing cells during development as it was shown (Murdoch and Roskams, 2007). Rabbit anti β-gal antibody (immunogen: recombinant full length protein; Abcam, cat# ab616; 1/2000) showed the expected signal in hair follicles (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999) and β-galactosidase positive cell were found in the inner ONL as expected (Booker-Dwyer et al., 2008). Phalloidin-488 (Molecular Probes, cat# A12379; dilution 1/200). Secondary antibodies were: donkey anti goat-Alexa 488, donkey anti rabbit-Alexa 555, donkey anti chicken-Alexa 568 and donkey anti rabbit-Alexa 488 (all of them from Invitrogen; used at 1:1,000), or Goat Fab anti rabbit (Jackson Immunoresearch, cat# 111-007-003).

RT-PCR

For total RNA extraction, total OE at E13 and P4 was removed by peeling the OE together with the lamina propia from the underlying cartilage, or OBs were dissected. Tissue was dissolved in 1 ml of TRIzol (Invitrogen) and frozen at −20°C. After thawing, 0.2 ml of chloroform was added, mixed thoroughly, incubated at RT for 3 min and centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 min. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a clean tube and the RNA was precipitated by the addition of 0.5 ml of isopropanol followed by 10 min incubation at RT and centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min. The precipitate was washed with 75% ethanol and the final pellet was resuspended in sterile water and dissolved by 15 min incubation at 55°C. To remove any traces of DNA, samples were treated with Turbo DNAse (Ambion), for 2 h. All samples were tested for DNA contamination by doing a PCR reaction with specific actin primers (R&D Systems).

RT-PCR for Wnt and Fz genes was done using Superarray kits (catalog # PM-041B and PM-042B for Wnt and Fz, respectively; see table 1 for primer sequences) following manufacturer instructions. Briefly, the PCR protocol was: 10 min at 95 °C followed by 30 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 55°C and 30 sec at 72 °C. At every age 2 independent RNA samples were obtained for each type of tissue and 2 cDNA and PCR reactions were performed with each sample. After densitometric analyses, only those genes with an expression value higher than 5% of GAPD were considered as expressed.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-PCR.

| Wnt-1 | TAGTGGCCGATGGTGGTAAGT | CTAGGTGTGAGCACCCTGGAT |

| Wnt-2 | CTTCAGCTGGCGTTGTATTTG | GGCAAACTTGATCCCGTAGTC |

| Wnt-3 | GGCTAAGTACGCGCTCTTCAA | GTTTCTCCGTCCTCGTGTTGT |

| Wnt-4 | AAGAGGAGACGTGCGAGAAAC | GGGAGTCCAGTGTGGAACAGT |

| Wnt-5a | GCTGATGGACGTTAGAGAGGG | CGGGCAGAGGAGTTGGTATAG |

| Wnt-6 | GCTCCTACAGTGTGGTTGTC | ATCTGGAGAGCCAGTTGGTC |

| Wnt-7a | GGTGCGAGCATCATCTGTAAC | AAGACAGTACGCTCTCCCAGC |

| Wnt-8a | AGGAGCCTGGAAGAACCGTAT | ATGGTTCACAGCCATCAAGTG |

| Wnt-9a | CCCTGACTATCCTCCCTCTGA | GCTCAAAGCGGAACTGGTACT |

| Wnt-10a | CTGAACACCCGGCCATACTT | TGTGGAGTCTCATTCGAGCAT |

| Wnt-11 | ATATCCGGCCTGTGAAGGACT | CTCCACCACTCTGTCCGTGTA |

| GAPD | TGACCACAGTCCATGCCATC | GACGGACACATTGGGGGTAG |

| Fz-1 | CAGTATTTCCATTTAGCCGCC | CAGCAGGAAAGAAGTGCCAAT |

| Fz-3 | GCCCTTTGTGAGACCAGGTTA | AGCCATTCTTCCTGGATCAGA |

| Fz-4 | AAGGCTAATGGTCAAGATCGG | CAAATCCACATGCCTGAAGTG |

| Fz-5 | GGCTACAACCTGACGCACAT | GTGGTAGCGGCTTGTGGTAGT |

| Fz-6 | GGCAATAGCACGGCTTGTAAT | GCAGCTAAGAACCACGTAATGG |

| Fz-7 | CTCCCTGTATCCAAGCCTCTC | CGGTACCGAGATGCCTTTCT |

| Fz-10 | GTGGATGTGTATTGGAGCCG | GCGAAGAGGCGGATGATATAG |

| Frzb | CTTAGACGCTTGGGAAGAGCA | CACTTTCGTTCCGAAGTCTCC |

| sFrp-1 | ACTTCTACCAGTCCATCGGGA | TGACTTGTGACCTGCTTGACA |

| sFrp-2 | TCGACGACCTAGATGAGACCA | CTTCACACACCTTGGGAGCTT |

| sFrp-4 | TCTTCCTTTGTGCCATGTACG | GTCATAGACCGGCAGCTCATC |

Organotypic and Dissociated Cell Cultures

Postnatal day 1 mice were rapidly decapitated and placed in cold sterile PBS. The OE from the nasal septum was dissected out and transferred to Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (Gibco). After a brief centrifugation (1500 rpm) the tissue was enzymatically digested using the Papain Dissociation System (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, NJ), following manufacturer instructions. Enzymatic reaction was carried out for 5 min to obtain explants, and for 1 h to obtain dissociated cells. Tissue was resuspended in Neurobasal Media (Gibco) supplemented with B-27 (Gibco), Penicillin (Gibco, 100 units/ml), Streptomycin (Gibco, 100 units/ml), and 200mM L-Glutamine (Gibco). Fifty μl of media containing explants were plated on 8 well chambered coverslips (Sigma-Aldrich), previously coated overnight with 50 μg/ml of Poly-D-Lysine (PDL, Sigma) followed by 20 μg/ml of Laminin at 37°C for 1 h. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, purified Wnt-5a (R&D Systems; concentrations raging from 0.01 to 5 μg/ml) and BrdU (Sigma, 20 μg/ml) were added for 24 h. Dissociated cells were plated on 2-chamber polystyrene glass slides (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) with the appropriate Wnt-5a concentration and incubated for 48 h. Cultures were fixed for 30 min with 4% PFA + 4% sucrose in PBS, pH 7.4, washed three times with PBS and stained for Neuronal Cell Adhesion Molecule (NCAM), BrdU or phalloidin. Nuclei were counterstained with DRAQ5 (Biostatus Limited, United Kingdom).

Image Acquisition and Analysis

To quantify BrdU incorporation, images were acquired using a Leica confocal microscope with a 40X objective and 1 μm optical sections. For each explant, quantification included serial analysis of all optical sections in a Z-stack. A minimum of 10 explants were measured for every treatment on each experiment, with 3 independent repetitions. Labeled cells were counted manually. A cell was considered BrdU positive if the label was restricted to a cell nucleus that was clearly located in the same optical section. Explant area was determined as total DRAQ5 labeled area and was measured using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). To determine the percentage of explants extending neurites, the total number of explants extending processes was counted manually using an Olympus BX51 epifluorescent microscope under a 20X objective. Dissociated cells images were obtained on an Olympus BX51 epifluorescent microscope and a Magnafire digital camera. The morphological features of explants and dissociated cells were quantified using Metamorph software version 6.3r2 (Molecular Devices).

Differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests to evaluate differences between selected groups. BrdU incorporation was similarly analyzed for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were done using the Prism 4.03 package (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Wnt and Fz mRNA Expression

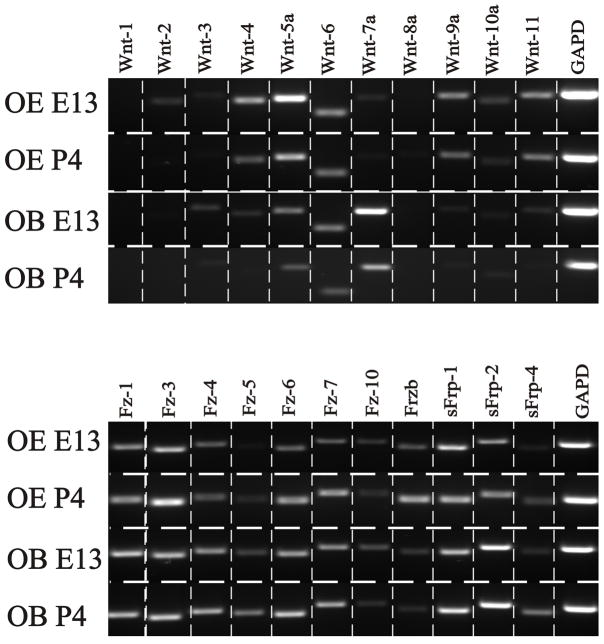

RT-PCR was used to assess the expression of candidate Wnt and Fz mRNA in the OE and OB at embryonic day 13 (E13) and postnatal day 4 (P4). With the exception of Wnt-1 and Wnt-8a, all Wnt family members were expressed in the OE at E13 and P4, with the exception of Wnt-2 and Wnt-3 which were only detected at E13 (Figure 1). In the OB Wnt-1, Wnt-2 and Wnt-8a were not expressed, while the remaining Wnts were detected at both ages. In contrast to the Wnts, all Fz and secreted Frizzled-related proteins (sFrp) mRNAs were found at both E13 and P4 in both the OB and OE. The RT-PCR analyses established the presence of both the Wnt ligands and their Fz receptors in the OE and OB during embryonic and perinatal development. To determine protein distribution in the olfactory system, we focused our subsequent analyses, based on the availability of reagents with specificity, on a limited subset from the Wnt and Fz family: Fz-1, Fz-3, Fz-7, Wnt-4, Wnt-5a and Wnt-11.

Figure 1.

Expression of Wnt and Fz mRNAs in the developing OE and OB. Figure corresponds to representative ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels showing RT-PCR products. Based on densitometric analyses, only those genes with a density value higher than 5% of GAPD were considered as expressed. Analyses demonstrate the expression of at least nine Wnt genes in the olfactory system, with the exception of Wnt-1 and -8a. It also can be seen that all the Fz and sFrp mRNAs studied are expressed during development. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPD) served as positive control as well as loading control. The corresponding GAPD product size is ~200bp.

Frizzled Receptors

Developmental studies were carried out only on embryos staged after fixation using Theiler criteria (Theiler 1972). In embryos in which age was determined according to the mating period or presence of the vaginal plug, prior to E13, development within litters varied across 3 Theiler stages (TS) which is the equivalent of 1 embryonic day. Thus, in order to increase the accuracy of our developmental analyses, for each mouse their developmental age was first established using TS, which was then translated into the nearest embryonic stage at 0.5 day intervals.

Frizzled-1

The olfactory placode is first observed as a thickening of the epithelium at TS14/E9. The first single Fz-1+ cells were found at TS16/E10, but these were inconsistent and seen in only a few embryos. By TS17/E10.5, as the olfactory pit is forming, Fz-1+ cells were found in all embryos (Figure 2 A). The number/density of Fz-1+ cells then increased through P4 (Figure 2 A–G). By P21 and in the adult, Fz-1+ expression in the OE decreased significantly (Figure 2 H, I; see below). At all ages examined, the position of the Fz-1+ cells in the OE and their bipolar appearance confirmed their identity as OSNs. Fz-1+ immunoreactivity was obvious in the OSN somata, apical dendrite, dendritic knob, cilia and axon (Figure 2 J). At TS21/E13, when ciliogenesis starts, immunolocalization was apparent in the developing cilia of single OSNs (Figure 2 J). To confirm localization in the cilia double labeling was carried out with adenylyl cyclase III, a downstream effector in the odor transduction pathway restricted to the cilia. As shown in Figure 2 K, Fz-1 and adenylyl cyclase III colocalize in the immature cilia extending from the dendritic knob of a Fz-1+ OSN. These data confirm the presence of Fz-1 in OSNs and suggest a developmentally regulated pattern of expression.

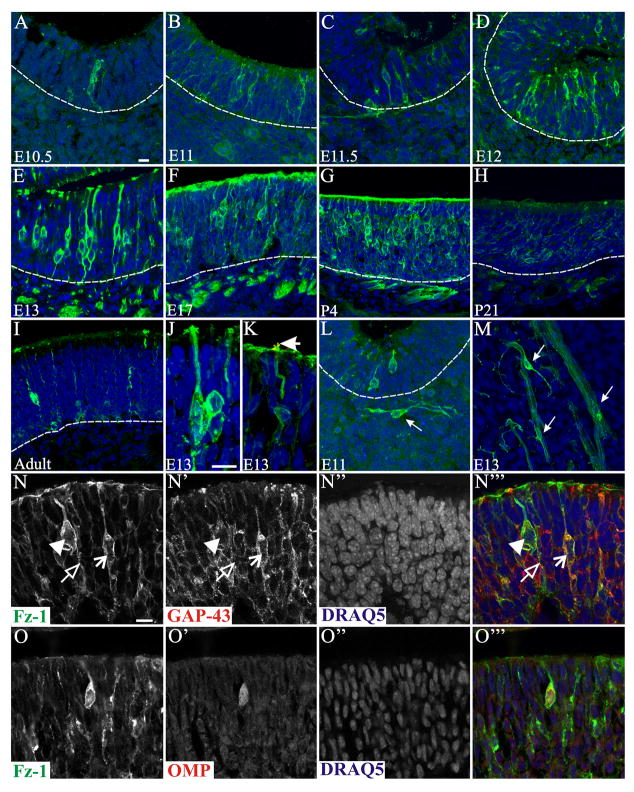

Figure 2.

Expression of Fz-1 in the developing and adult olfactory epithelium. Horizontal (A–D) and coronal (E–I) sections through the olfactory pit (A, B) and epithelium (C–I) showing expression of Fz-1 (green) in OSNs. Expression could be detected in the OSN axons in the underlying lamina propria as well as in the soma, apical dendrite, knob and developing cilia (J). Double staining for ACIII show complete colocalization with Fz-1 in the developing cilia at E13 (yellos in K, arrow). Fz-1-expressing cells were also observed migrating in the mesenchyme between the OE and the OB in close association with OSNs axon bundles that were also Fz-1 positive (arrows in L, M). Double labeling studies showed a transition from GAP-43+/Fz-1− (red cell, open arrowhead) to light GAP-43/Fz-1+ (green cell, filled arrowhead) and also high expression levels of both markers (yellow cell, arrow; N-N‴), as well a colocalization with OMP (O-O‴). Colocalization was observed as early as E13, the first time point when OMP expression could be detected. Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Scale bars = 10 μm: shown in (A) for A–I, L & M; shown in (J) for J & K; shown in (N) for N & O.

To determine if Fz-1 is preferentially expressed by immature or mature OSNs, double labeling studies were carried out using antibodies to growth associated protein 43 (GAP-43), which is found in immature OSNs and, olfactory marker protein (OMP), which is found in mature OSNs. Colocalization of GAP-43 and Fz-1 was abundant but not complete and there were some Fz-1 cells colocalizing with OMP (Figure 2O–O‴). GAP-43+/Fz-1+ labeled cells tended to localize in the deeper half of the OE, consistent with previous findings for GAP-43, whereas OMP+/Fz-1+ cells were more superficial, as expected for OMP-expressing cells. There appear to be a progression from deep GAP-43+/Fz-1− cells (Figure 2 N, open arrowhead) to GAP-43+/Fz-1+ (Figure 2 N, arrow) cells to more superficial light-GAP-43+/Fz-1+ (Figure 2 N, solid arrowhead), the latter perhaps in transition to OMP+.

At embryonic stages ranging from TS18/E11 to TS21/E13 Fz-1+ cells could be observed exiting the OE, or migrating in the mesenchyme underneath the OE (Figure 2 L) as well as in close association with the OSN axon bundles (Figure 2 M). By TS25/E17 there was no evidence of Fz-1+ cells in the intermediate zone between the OE and OB. Several populations of cells are thought to exit the OE during embryonic development including GnRH neurons (Schwanzel-Fukuda and Pfaff, 1989), OMP+ cells (De Carlos et al., 1995), and more recently OR+ cells (Schwarzenbacher et al., 2006). It seems reasonable to speculate that some of these populations may show colocalization with the Fz-1+ cells we identify here, but further studies are necessary.

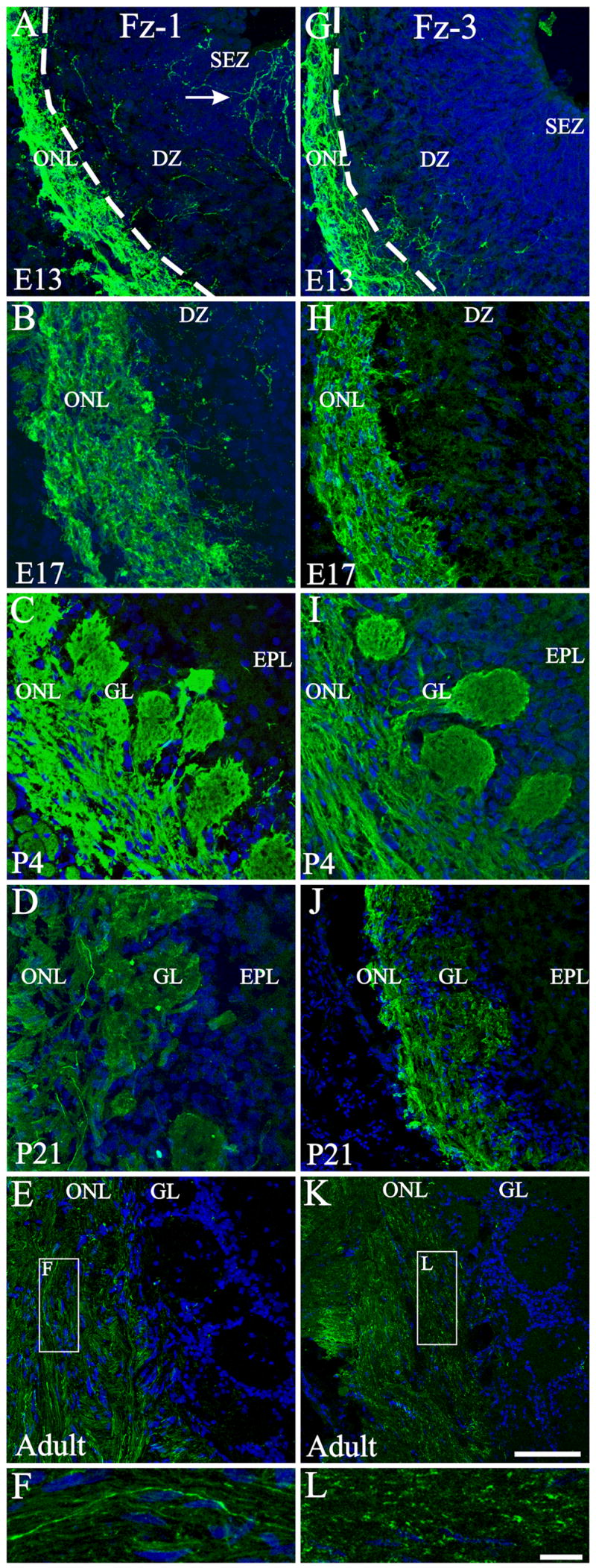

Fz-1+ OSN axons were first observed at E11 projecting toward the telencephalic vesicle (data not shown). As the OB differentiated, Fz-1 was expressed in the developing olfactory nerve layer (ONL) and subsequently in the ONL and glomeruli by P4 (Figure 3 A–E). At E13 some Fz-1+ axons extended through the nascent OB to terminate in a juxta-ventricular region, much as has been described (Gong and Shipley, 1995) for GAP-43+ OSN axons (Figure 3 A, arrow). Double labeling for Fz-1 and GAP-43 suggests these are the same subpopulation of axons (Supplemental Figure S1 A–D). By P21, some axons in the ONL and glomeruli stained intensely for Fz-1, while in others expression was much weaker (Figure 3 D). These differences were even more apparent in the adult when some Fz-1+ axons were identified within the ONL and glomeruli (Figure 3 E, F).

Figure 3.

Developmental expression of Fz-1, Fz-3 in the olfactory bulb. At E13 (A), Fz-1 is highly expressed in the developing ONL, with some OSN axons reaching the ventricular region (arrow). As the olfactory bulb develops the expression remains in the ONL and it extends to the newly formed glomeruli (B, C). At later ages the overall expression level decreases with some high-level-expressing axons intermingled with low-level-expressing (D) or Fz-1− axons (E, F). Fz-3 expression was also observed from E13 onwards in the developing ONL and glomeruli (G–I) and the overall expression decreased by P21 (J) and in the adult it remains as punctuate in the ONL (K, L). F, L: High magnifications of the rectangles shown in E and K respectively. Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm: shown in (K) for A–E, G-K; 10 μm: shown in (L) for F & L. DZ: dendritic zone; EPL: external plexiform layer; GL: glomerular layer; ONL: olfactory nerve layer; SEZ: Subependymal zone. Dotted line in A and G marks the limit between the developing ONL and the DZ.

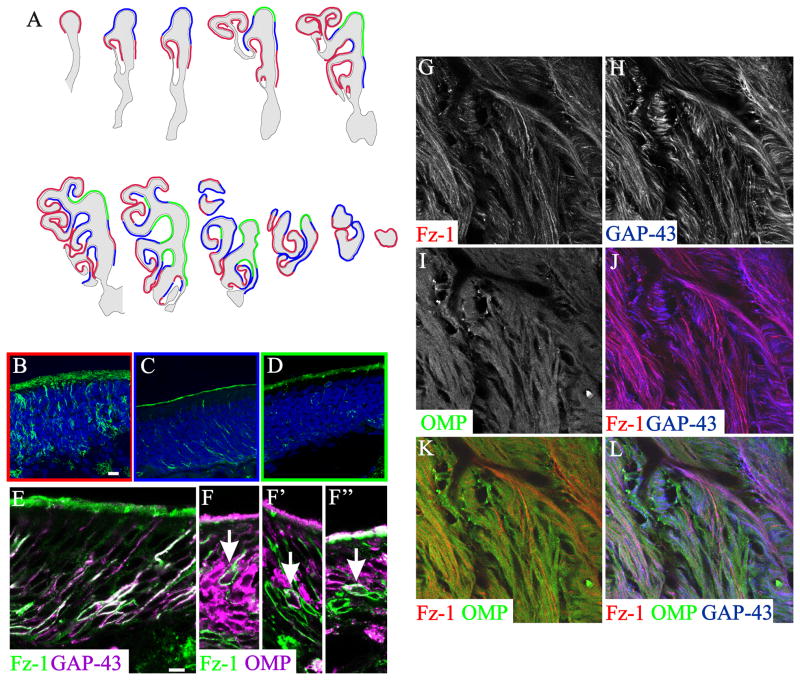

We next asked if there was significance to the spatial organization of Fz-1 expression in the OE or the OB glomerular targets of Fz-1+ OSN axons. In the OE we distinguished three different levels of staining: high with many Fz-1+ OSNs; medium with intermediate levels of staining; and low, with only a few scattered Fz-1+ OSNs (Figure 4 A–D). In general, lateral areas of the OE had higher levels of staining than dorso-medial regions (Figure 4 A). Triple staining for OMP/Fz-1/GAP-43 showed that the majority of the Fz-1+ cells were GAP-43+, while only a few Fz-1+/OMP+ or Fz-1+ only cells were observed (Figure 4 E, F-F″). Consistent with the colocalization seen in the OE, in the ONL of the OB the majority of Fz-1+ OSN axons were also GAP-43+ (Figure 4 G–L).

Figure 4.

Expression of Fz-1 in the adult olfactory epithelium and olfactory nerve layer. A: Schematic representation of an adult mouse nasal cavity every 400μm from rostral (top left) to caudal (bottom right). As the respiratory epithelium also presents Fz-1 expression, the olfactory epithelium was determined by OMP expression. We subjectively divided the olfactory epithelium into areas presenting many (red), intermediate (blue) or few (green) Fz-1-expressing cells. B–C: representative examples of OE areas with many (B), intermediate (C) or few (D) Fz-1-expressing cells. Most of the Fz-1+ cells were also GAP-43+ (D), but some examples of Fz-1+/OMP+ cells could also be observed, albeit less frequently (arrows in F-F″). In the ONL most of the Fz-1+ axons showed colocalization with GAP-43+ axons (G, H, J, L), and almost no colocalization with OMP+ axons (G, I, K, L). Scale bar = 10 μm: shown in (B) for B–C; 10 μm: shown in (E) for E–L.

The expression for Fz-1 in the glomerular layer of the OB was not uniform. Some glomeruli were homogenous in Fz-1 expression (Figure 5 A, B, D), while others were notably heterogeneous (Figure 5 C, E–I) or did not exhibit any Fz-1+ OSN axons (Figure 3 E and 5 J). Based on the intensity of the staining, even among those showing homogenous expression there were differences in levels of expression (compare Figure 5A, B with 5 D). Of those glomeruli with heterogeneous expression, the number of Fz-1+ axons was always low, but variable (compare Figure 5 E–I). Labeled glomeruli were found superficially (Figure 5 A, B, D–F, H) or deeper (Figure 5 C, G, I) in the glomerular layer, and the sizes of the labeled glomeruli varied significantly. Triple staining for OMP/Fz-1/GAP-43 showed that while the majority of Fz-1+ axons are GAP-43+ in the ONL, with the glomerular neuropil they generally colocalized with OMP (Figure 5 K-K‴), although colocalization with GAP-43 could also be observed (Figure 5 L-L‴).

Figure 5.

Expression of Fz-1 in the adult olfactory bulb. A–J: Some glomeruli show different levels of Fz-1 expression (A–I) or did not exhibit any Fz-1+ OSN axons (J). Arrows in H and I point to single axons entering a glomerulus. Differences in layer thickness are due to a differential position of the glomeruli across the OB. Triple labeling of OB sections with antibodies against Fz-1, OMP and GAP-43 showed that most of the Fz-1+ glomeruli were also OMP+ (K-K‴, arrow); nonetheless, some colocalization of Fz-1 with GAP-43 could also be observed (L-L‴). The distribution of Fz-1+ glomeruli was plotted for four OBs (M) or the mean of all of them (N) on 2D flat graphs. The density of Fz-1+ glomeruli is represented in pseudocolors (scale in N). Glomerular location was determined in 20° intervals with the ventral midline defined as 0°, lateral as 90°, dorsal as 180° and lateral as 270°. Scale bar = 50 μm: shown in (A) for A–J; 50 μm:shown in K; 10 μm: shown in L.

We next asked if there was any significance in the organization of Fz-1 labeled glomeruli in the adult OB. Because a large number of glomeruli were stained, it seemed unlikely that they were associated with only 1 odor receptor. Therefore, we instead analyzed the spatial distribution of the Fz-1+ glomeruli. Four OBs were serially sectioned and every tenth section was stained for Fz-1. We then divided each OB into 20° intervals; 0° was ventral, 90° medial, 180° dorsal and 270° lateral. The Fz-1positive glomeruli were counted within each interval around the OB circumference. We did not count those glomeruli that presented very few axons (e.g. Figure 5 G–I). As it can be seen in Figure 5 M, N, despite differences in the total number of Fz-1+ glomeruli between OBs, the areas of expression remained relatively uniform among different OBs. Most of Fz-1 expressing glomeruli are positioned in the anterior medial-dorsal part, in the caudal dorsal area, and ventrally in the last two thirds of the OB. Moreover, Fz-1+ glomeruli tend to be clustered rather than scattered across the entire OB.

Frizzled-3

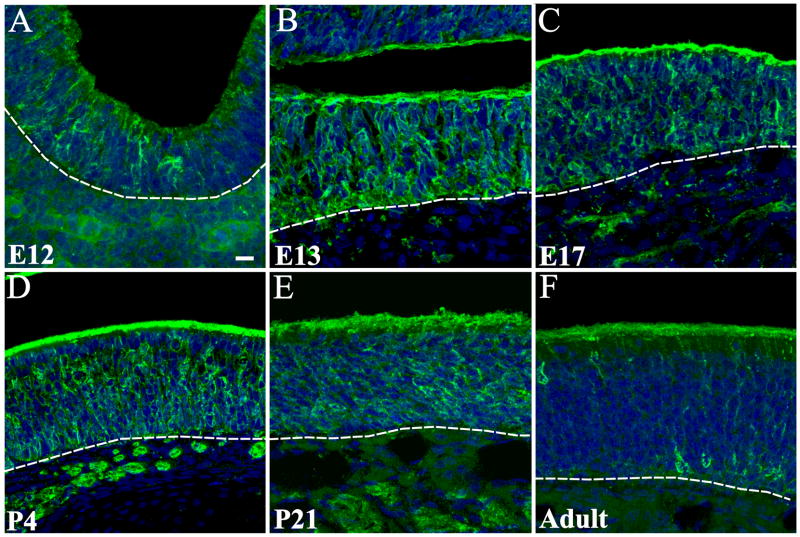

In the OE Fz-3 labeling was first detected at TS20/E12 in a few cells, but 24 hours later, at E13, the expression in the OE was ubiquitous (Figure 6 A, B). Fz-3 immunoreactivity remained relatively high through P21 but in the adult, only a few cells expressed Fz-3 (Figure 6 A–F). In the OB, the staining pattern was very similar to that observed for Fz-1 (Figure 3 G–K), except that no Fz-3+ fibers extending up to the ventricle in the embryo could be seen, as was the case for Fz-1. It is also interesting to note that the axonal distributions of Fz-1 and Fz-3 were different in the adult. While Fz-1 labeled the entire axonal process, Fz-3 was more restricted with a punctate distribution (compare Figure 3 F and L).

Figure 6.

Expression of Fz-3 in the olfactory epithelium during development. In coronal sections through the OE (A–F) Fz-3 expression (green) could be observed across the entire OE and also in the OSN axons in the underlying lamina propria (dotted line). A marked decrease in overall expression was observed after P21. Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Scale bar = 10 μm: shown in (A) for A–F.

Frizzled-7

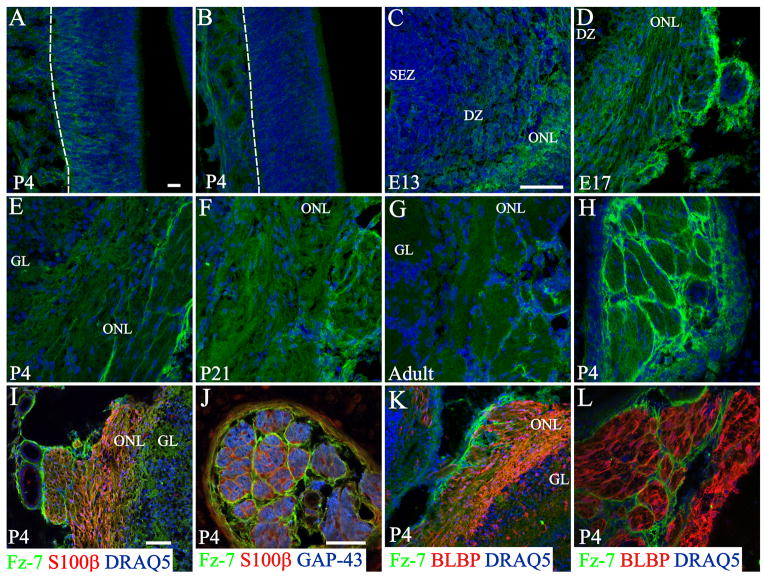

In the OE Fz-7 expression was heterogeneous. At P4 there were regions where it was predominately found in unidentified cells in the basal portion of the OE (Figure 7 A and Supplemental Figure S2 C) or through the entire thickness of the epithelium (Supplemental Figure S2 B). Of interest, the dorsal region was completely devoid of Fz-7 expression (Figure 7 B and Supplemental Figure S2 D). In the OB Fz-7 expression was first found in the developing ONL at E13 (Figure 7 C). By E17 the organization of Fz-7+ processes surrounding axon fascicles suggested that Fz-7 was localized in olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs), predominately the OECs located in the outermost layer of the ONL (Figure 7 D) as well as in the meninges surrounding the OBs. This pattern remained until adulthood, though the overall expression seemed decreased (Figure 7 E–G and Supplemental Figure S2 E). Fz-7 expression was also observed in cross sections of the olfactory nerve fascicles beneath the OE (Figure 7 H and Supplemental Figure S2 F), prior to their crossing the cribriform plate. In order to determine if the subpopulation of cells we identified belonged to a class of OECs, we double-stained with S100β, that labels a subpopulation of OECs, or Brain Lipid Binding Protein (BLBP), a marker of radial glia in the CNS that is also strongly expressed in OECs (Carson et al., 2006). Surprisingly, none of the OEC markers colocalized with Fz-7 (Figure 7 I, K). Moreover, in cross sections of the olfactory nerve prior to crossing the cribriform plate, Fz-7-expressing cells seem to be surrounding the classic S100β or BLBP OECs, suggesting of a second layer of ensheathing cells (Figure 7 J, L).

Figure 7.

Fz-7 expression in the developing olfactory bulb and olfactory epithelium. In the OE a heterogeneous distribution was observed with regions with different levels of expression (A), and others completely devoid of staining (B). In the developing OB (C–G) Fz-7 expression (green) was first observed as a diffuse staining in the developing olfactory nerve layer (C) and later in cells surrounding the axon fascicles (D–G). In cross sections of large olfactory nerve bundles beneath the OE, Fz-7 expression was also associated with cells surrounding the axon bundles (H). Double staining with S100β (I, J) or BLBP (K, L) showed no colocalization. Instead, it seems that Fz-7-expressing cells surround classic S100β or BLBP OECs, suggestive of a second layer of ensheathing cells. In J it can be seen Fz-7+ cells surrounding S100β+ cells which in turn ensheath GAP-43 expressing axons. Scale bar = 50 μm: shown in (A) for A–H; 50 μm: shown in (I) for I & K; 10 μm: shown in (J) for J & L.

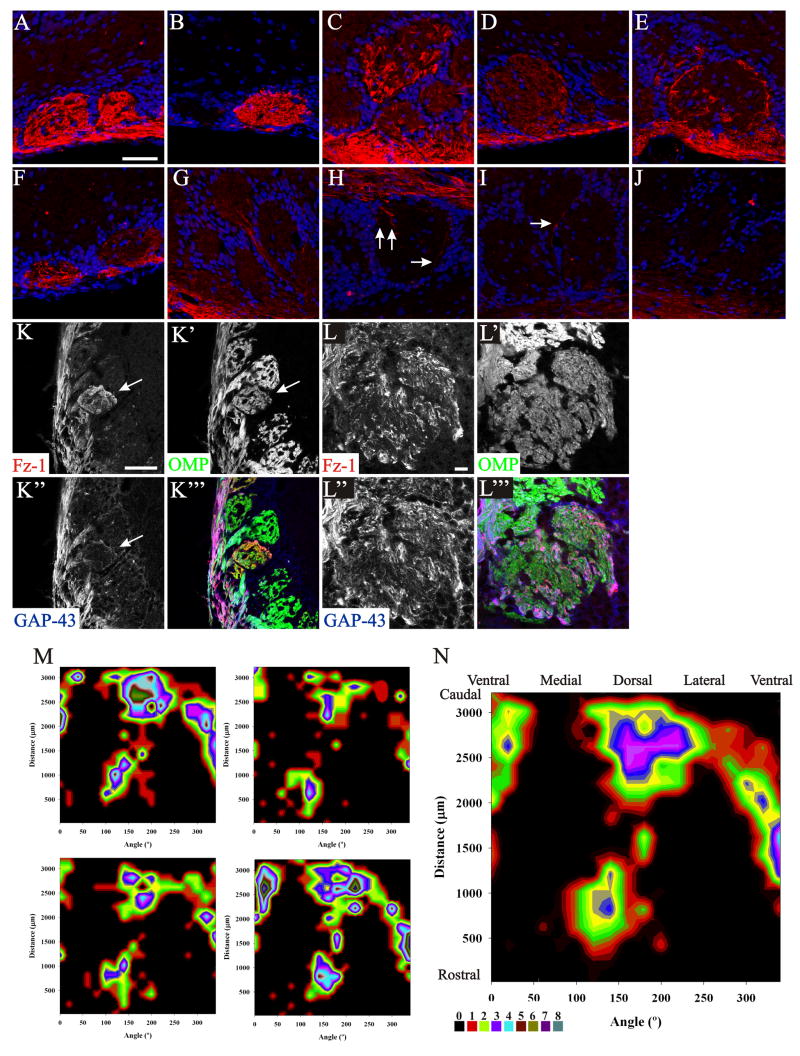

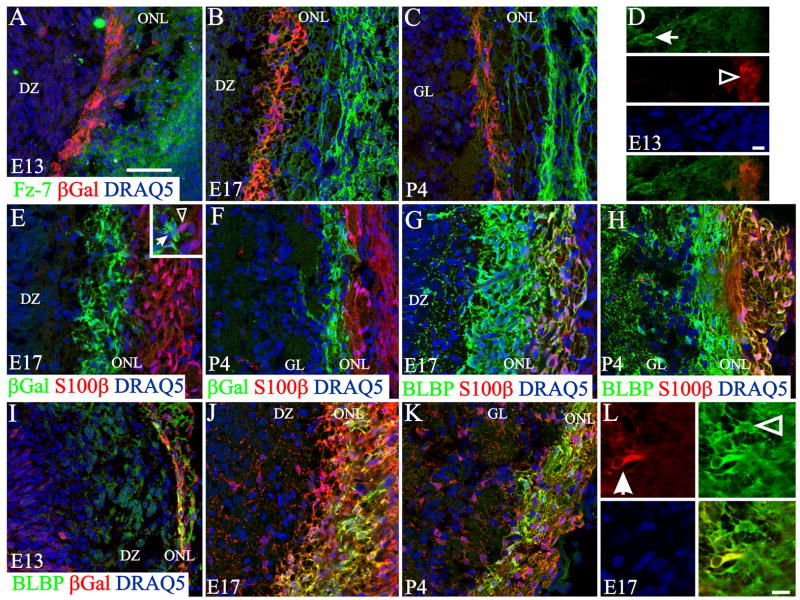

In response to the challenge of characterizing the Wnt signaling and transduction pathways, several transgenic mouse strains have been developed in which activation of the canonical pathway can be visualized by β-galactosidase (βgal) expression after β-catenin stabilization. In the BAT-gal mice (Maretto et al., 2003), βgal+ cells were recently identified in the ventromedial part of the developing OB, a region in which Fz-7 is also strongly expressed as shown by in situ hybridization at E14.5 (Zaghetto et al., 2007). Using the TOPGAL strain of mice (DasGupta and Fuchs, 1999), a more recent study suggested a developmental pattern of Wnt-responsive cells (Booker-Dwyer et al., 2008). Because the identity of these βgal-expressing cells remains controversial, we used the TOPGAL mice and found expression of both Fz-7 and βgal in the developing OB at E13 (Figure 8 A). Despite expression in the same area, these cells appear as distinct populations, with no evidence of colocalization of βgal and Fz-7 (Figure 8 D). By E17 the difference was more noticeable and it remained so through P4 (Figure 8 B, C). Fz-7-expressing cells in the OB remained in the outer ONL, while βgal+ cells were in the inner ONL and closely apposed to the developing glomerular layer. This is in agreement with Booker-Dwyer et al.(2008), but in contrast to Zaghetto et al. (2007) who found βgal+ cells in neonates in the OMP+/S100+ layer (outer ONL) and not in the OMP+/S100− layer (inner ONL). In the adult we found no evidence of βgal+ cells (data not shown). Finally, to determine if the subpopulation of cells we identified belonged to a class of OECs, we performed a series of double-label immunohistochemical stains. We first showed that perinatally the βgal+ and the S100β+ cells were two different cell populations (Figure 8 E, F.). Then we established that the S100β+ is a subpopulation of the BLBP+ cells positioned, as expected in the outer ONL (Figure 8 G, H). Finally we showed that as early as E13 and continuing through P4 (Figure 8 I–L), the βgal+ cells were co-labeled with BLBP, confirming that these βgal expressing cells are a subpopulation of OECs.

Figure 8.

Wnt responsive cells are a subpopulation of OEC different from Fz-7 cells. Sections from TOPGAL mice (which express βgal after activation of the canonical Wnt pathway) were stained for βgal (red, A–D) and Fz-7 (green, A–D). Fz-7 and βgal+ cells were both found in the ONL at all ages studied (A–D) but from E13 on these cells seem to represent two independent populations. Fz-7+/βgal− cell (arrow) could be clearly distinguished at E13 from Fz-7−/βgal+ cells (open arrowhead). Perinatally, these βgal+ cells were positioned in the inner ONL and differ from the S100β-expressing cells which are found in the outer ONL (E–F). Moreover, closely apposed cells expressing βgal (E inset, arrow) do not express S100β (E inset, open arrowhead). Double staining with BLBP, a general marker of OECs, and S100β support the notion that while BLBP+ cells are found throughout the entire ONL, S100β+ cells are localized in the outer ONL. On the other hand, double staining for BLBP (I–L) and βgal showed that these Wnt responsive cells are OECs. L: βgal+/BLBP+ cells (arrow) are a subpopulation of BLBP+ cells (open arrowhead). Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm: shown in (A) for A–C, E–K; 10 μm: shown in (D); 10 μm: shown in (L).

Wnt Molecules

Wnt-11

Overall, in the OE the expression levels of Wnt-11 were low, and all cell types seem to express Wnt-11 at perinatal stages (Supplemental Figure S3). In the central olfactory system high levels of Wnt-11 were detected only in isolated cells in the anterior olfactory nucleus (Supplemental Figure S3).

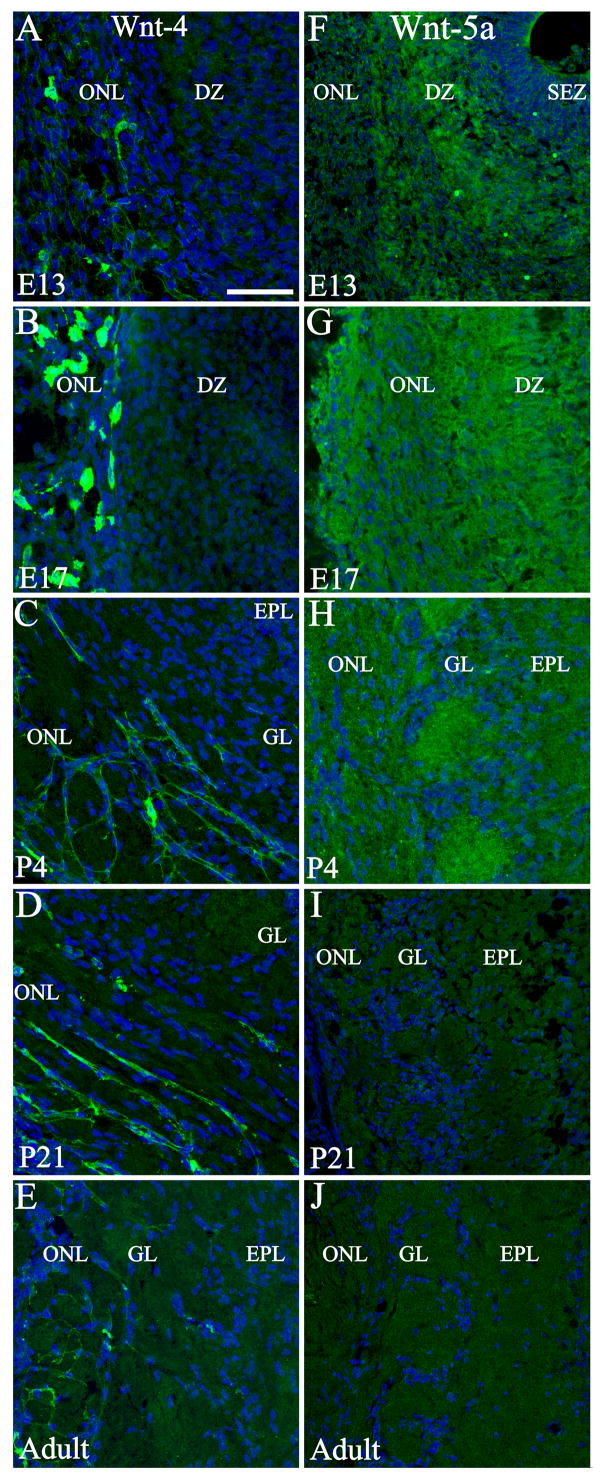

Wnt-4

Wnt-4+ cells were not observed in the OE at any of the ages studied, but some cells resembling fibroblasts were observed in the lamina propria deep to the OE (data not shown). In the developing OB two populations of cells were Wnt-4+. The first appeared fibroblast-like, and remained in the meninges until adulthood. The second population was observed at E13 in the developing ONL (Figure 9 A). These differentiated as OECs that extended thin processes in close apposition to and surrounding the axon fascicles (Figure 9 B, C). The processes appeared to increase in length through P21, though the expression level of Wnt-4 subsequently decreased to lower levels in the adult (Figure 9 D, E). No expression of Wnt-4 was observed in cross sections of olfactory nerve bundles deep to the OE, in contrast to the localization of Fz-7 in that region.

Figure 9.

Developmental expression of Wnt-4 and Wnt-5a in the olfactory bulb. At E13 (A), Wnt-4 was expressed in cells located in the developing ONL and in the periphery of the developing ONL. This expression pattern continued during development (B–E) and two different populations could be differentiated up to adulthood; one population stays in the meninges while the other differentiates into OECs. Wnt-5a expression was observed in the OB during embryonic (F, G) and early postnatal (H) development. Despite a rather homogenous distribution, higher intensity was observed in the dendritic zone (F) and in glomeruli (H). No distinguishable expression was detected at P21 (I) or adult (J) stages. Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Scale bar = 50 μm: shown in (A) for A–J. DZ: dendritic zone; EPL: external plexiform layer; GL: glomerular layer; ONL: olfactory nerve layer; SEZ: Subependymal zone.

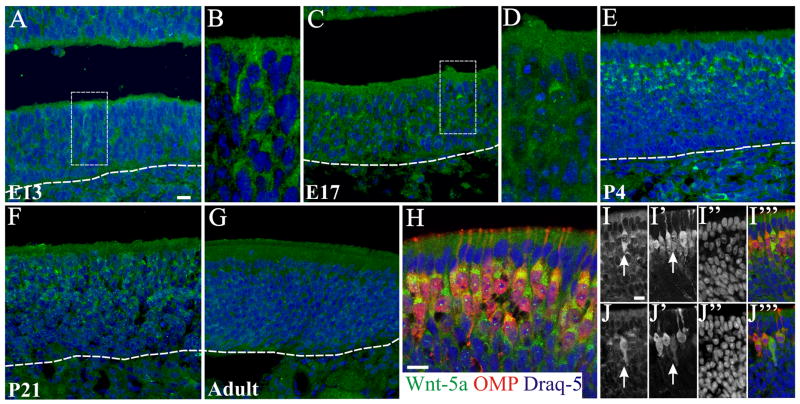

Wnt-5a

Wnt-5a+ cells were found in the OE as early as E13 (Figure 10 A, B), with immunoreactivity predominately in the cytoplasm. At E17 the strongest Wnt-5a expression appears to cap the nucleus of OSNs apically in a position that is consistent with the localization of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus (Figure 10 C, D). By P4 all the mature OSNs presented this characteristic expression as revealed by colocalization with OMP (Figure 10 E, H). Wnt-5a expression decreased at P21, and was totally absent in the adult OE (Figure 10 F, G). By P4 and P21 it was possible to detect a few cells distributed across the OE where Wnt-5a is spread throughout the OSN cell body. These cells were in general lightly OMP+ (Figure 10 I, J). In the OB Wnt-5a was detected between E13 and P4 but expression could not be associated with any specific cell type (Figure 9 F–H); the staining was diffuse suggesting that the protein may have been secreted. At E13 Wnt-5a was observed in the dendritic zone of the developing OB (Figure 9 F), and by E17 and P4 all layers showed Wnt-5a expression (Figure 9 G, H). Higher expression levels were observed in the glomeruli at P4 (Figure 9 H), a period during which glomerular organization is maturing with significant synaptogenesis. Detectable levels of Wnt-5a were not found in the OB at P21 or in the adult (Figure 9 I, J).

Figure 10.

Wnt-5a expression in the developing olfactory epithelium. At E13 (A, B) Wnt-5a staining (green) was observed as a deposit in the cytoplasm of OSNs (B is a high magnification of the rectangle shown in A). By E17 (C, D) an increase in Wnt-5a+ cell number as well as higher accumulation was observed (D is a high magnification of the rectangle shown in C). By P4 (E) mature OSNs show a distinctive staining as a cap over the nucleus, which remained at lower levels at P21 (F), and disappears in the adult (G). At P4, double labeling with OMP (red) show that all mature OSN express Wnt-5a (H). At this age it could also be observed some cells expressing Wnt-5a throughout the entire cytoplasm (arrows in I, J). These cells were lightly OMP+ (red). Nuclei are stained with DRAQ5 (blue). Scale bars = 10 μm: shown in (A) for A, C, E–G, and shown in (H); shown in (I) for I & J.

Organotypic and dissociated cell cultures

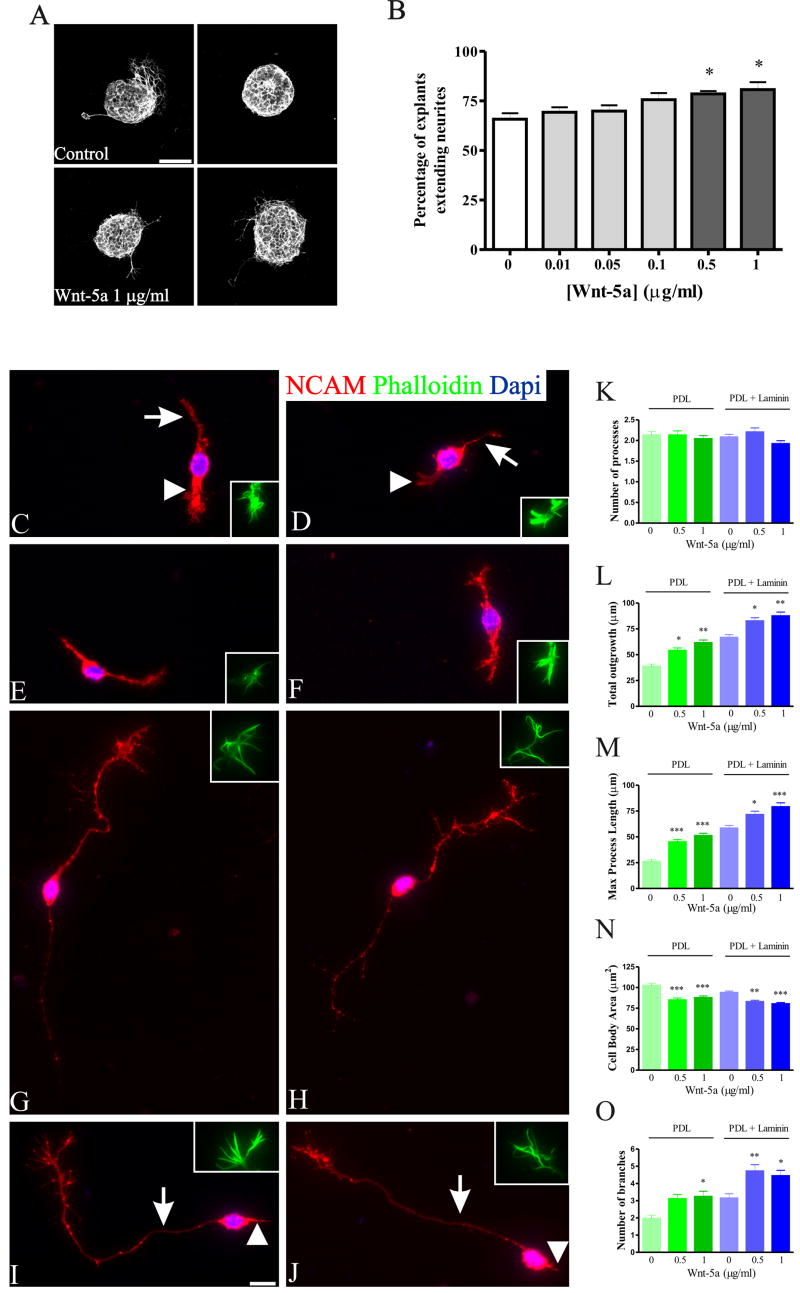

The data thus far suggest that Wnt-Fz family members are present in the OE and OB in spatio-temporal gradients that may influence the outgrowth of OSN axons. To test this hypothesis we characterized the function of one of our candidates on axon outgrowth from OE explants; we examined the effect of Wnt-5a on OSN axons because a) of its early and developmentally regulated expression in OSNs, b) it has been demonstrated that Wnt5a influences axonal growth of cultured hippocampal neurons (Zhang et al., 2007) and induces axonal extension of post-crossing commissural axons (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003) and c) is able to induce differentiation of immature primary midbrain precursor cells into mature neurons (Schulte et al., 2005). Under control conditions approximately 60% of the explants extended neurites within 48 h. Low concentrations of Wnt-5a added to the media (≤ 0.1 βg/ml) did not produce any significant effect on the percentage of explants extending neurites (Figure 11 B). However, higher concentrations (0.5 and 1 μg/ml) significantly increased the number of explants extending neurites. While 5 μg/ml of Wnt-5a added to the explants reduced the number of explants extending neurites, later experiments using dissociated OSN proved this concentration to be toxic (data not shown).

Figure 11.

Wnt-5a increased total outgrowth and altered growth cone morphology of OSNs in culture. A: Two representative explants from control (top row) and 1μg/ml Wnt-5a treated (bottom row). B: The percentage of explants extending neurites at different Wnt-5a concentrations showed a dose dependent response. All the explants from 8 well coverslips were counted and three repetitions were done for each condition. *: P<0.01 compared to control. Total number of explants counted for each condition was: Control=633; Wnt5a 0.01μg/ml = 499; Wnt5a 0.05 μg/ml = 483; Wnt5a 0.1 μg/ml = 545; Wnt5a 0.5 μg/ml = 654; Wnt5a 1 μg/ml = 598. Four control (C–F) and 1 μg/ml Wnt-5a treated (G–J) representative dissociated cells grown on PDL + Laminin are shown. Inserts show a detail of phalloidin stained growth cones of each cell. Arrows and arrowheads in C, D, I, J point to the primary and secondary neurites respectively. Graphs show quantification of number of processes (K), total outgrowth (L), length of maximum process (M), cell body area (N) and number of branches (O) for dissociated cells, cultured on two different substrates: PDL (50 μg/ml, green bars) or PDL + Laminin (20 μg/ml) (blue bars). K: the number of processes, which is representative of OSN cells shape, remained unaltered at 0.5 and 1 μg/ml of Wnt-5a. Total outgrowth (L) and length of the maximum process (M) increased in a dose-response manner with Wnt-5a. On the contrary, cell body area was significantly reduced (N) probably as a result of an increase in total outgrowth. The addition of Wnt-5a also increased the number of branches (O), most of which was accounted by different morphology in the growth cones. Data on graphs represent the mean ± SEM. *: P<0.05; **: P<0.01; ***: P<0.001. Scale bar = 50 μm in A; 10 μm: shown in (I) for C–J.

While organotypic cultures at least partially preserve the in vivo milieu, it is hard to evaluate the behavior of individual cells. We therefore turned to a model using dissociated OSNs to determine the effects of exogenously applied Wnt-5a on OSN axon extension. Laminin, which is present in the olfactory system, can influence OSN outgrowth (Kafitz and Greer, 1997). In order to test whether Wnt-5a effect was dependent on culture substrate, two different conditions were tested: PDL (50 μg/ml) or PDL + Laminin (20 μg/ml). In the OE, OSNs are bipolar cells extending an apical dendrite to the surface and an axon into the underlying lamina propria. In culture, under control conditions dissociated cells developed two processes (Figure 11 C, D), a long primary neurite (presumably the axon) and a shorter process (presumably the dendrite); the addition of Wnt-5a did not alter the bipolar OSN morphology, as shown by NCAM staining (Figure 11 K). As expected from the organotypic cultures, the total outgrowth as well as the length of the maximum process showed a dose-response effect with Wnt-5a addition on both substrates analyzed (Figure 11 C–J, L, M). Interestingly, although the primary bipolar morphology was preserved, with the addition of Wnt-5a some cells showed two long neurites extending from the cell body (Figure 11 G, H) instead of one long primary neurite and a shorter process (Figure 11 I, J). Addition of Wnt-5a also reduced the area (μm2) of the somata, most likely a reflection of an increase in total process outgrowth (Figure 11 N). Under control conditions, Laminin increases neurite outgrowth, and the Wnt-5a effect was independent of the substrate.

Counterstaining the cells with phalloidin, which is a reliable marker of growth cones because of its high affinity for polymerized actin, demonstrated an effect of Wnt-5a on growth cone morphology. While in control conditions most of the growth cones exhibited short thick foliopodia like structures (Figure 11 C–F inserts), after Wnt-5a addition growth cones showed more filopodia-like structures that included multiple thin elongated extensions from the body of the growth cone (Figure 11 G–J inserts). To quantify these differences, and taking the advantage that OSN axons show almost no branching, we analyzed the number of branches as a measure of differences in growth cone morphology. As expected, most of the branching came from bifurcations in the growth cones and it showed a significant increase after the addition of Wnt-5a (Figure 11 O). Therefore, Wnt-5a increases neurite extension and growth cone morphology of OSN, without altering OSN bipolar morphology.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate the expression of members of the Wnt-Fz families in the OE and OB during development. Expression occurs in spatio-temporal gradients that implicate Wnt/Fz molecules in the outgrowth and perhaps coalescence/targeting of OSN axons in the OB. The functional significance of Wnts is further supported by our in vitro assays in which outgrowth was significantly increased with the addition of Wnt-5a to the media.

Wnt molecules are implicated throughout the nervous system in cell proliferation, migration, polarity, axon guidance and synapse formation (detailed information can be found on the Wnt Homepage, http://www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntgenes/mousewnt.html). In the olfactory system, axons from newly generated OSNs navigate from the OE into the OB. In the OB, axons from OSNs expressing the same OR converge into specific glomeruli where they synapse with projection neurons and local interneurons. ORs and functional activity have been implicated in OSN convergence, but they do not fully account for OSN axon behavior, additional cooperative mechanisms must also be operating. Here, we show the expression of several members of Wnt and Fz families that are excellent candidates for contributing to mouse olfactory system development. Several of the molecules we characterized by RT-PCR have been implicated, in other systems, in axon guidance (Wnt-3, -4 and Fz-3, sFRP1), neuronal differentiation (Wnt-2, -5a and -7a) and neurogenesis (Wnt-3, -3a, -5a). Having shown that Fz and Wnt mRNAs are expressed, we characterized protein expression patterns in the OE as the next step in identifying possible candidates involved in axon guidance.

The expression of Fz-1 in OSNs is consistent with involvement in OSN axon extension and perhaps synapse formation, not only during development but also in adult where OSNs continue to be generated. The first OSN synapses appear in the OB around E15, but it is not until ~P21 that synapse formation reaches a peak (Hinds and Hinds, 1976). Fz-1 expression is consistently detected 1.5 days after the initial formation of the olfactory placode and persists until P21, after which it declines and stabilizes at adult levels. Since there is ongoing turnover of OSNs in the adult, the sustained levels of Fz-1 expression in the adult OE and OB suggest a role of Fz-1 in OSN axon extension and synapse formation in both the developing embryo and adult. We previously demonstrated that β-catenin is enriched in the inner ONL and glomeruli (Akins and Greer, 2006a). β-catenin interacts with cadherins (Weis and Nelson, 2006) which are important for adherens junction formation (Akins et al., 2007). It seems reasonable to speculate that in the OB Fz-1 stabilizes β-catenin, which would contribute to both the fasciculation of molecularly homogeneous axons in the inner ONL and their terminals in the glomeruli following the formation of synapses.

Recently, attention has turned to candidate adhesion molecules, including Kirrel-2, Kirrel-3, ephrin-A5, EphA5, and BIG-2, all of which show glomerular specific expression (Kaneko-Goto et al., 2008; Serizawa et al., 2006). Our data on Fz-1 expression are analogous, including developmental increases in Fz-1 expression (cf. (Saito et al., 1998). Both Fz-1 and Fz-10, which we show here are developmentally expressed, are candidate receptors for the Wnt ligand Wnt-7b (Wang et al., 2005); Wnt-7b mRNA is present in the developing olfactory system (Zaghetto et al., 2007). Whether Wnt-7b may exert its effect(s) via one or both of these candidate receptors remains to be determined, but regardless, it now seems clear that in vivo expression of this member of the Wnt-Fz families occurs in the spatio-temporal domains necessary for a role in OSN axon extension/guidance.

Fz-3 expression lagged 2 days behind Fz-1, but could be similarly localized throughout the OSN somata and axons. The expression of Fz-3 in the epithelium leads us to hypothesize that this receptor may have a role in the orientation of cells in the olfactory epithelium. Fz-3 plays an important role together with Fz-6 in the orientation of a subset of auditory and vestibular sensory cells (Wang et al., 2006a). As we also observed Fz-6 mRNA expression in the OE, these two receptors may have a similar polarizing functional in the olfactory system. In addition, the presence of Fz-3 in the OSN axons and in particular the distribution of Fz-3 observed in the adult ONL is suggestive of expression in the growth cones. Consequently, it seems reasonable to suggest that Fz-3 may also be involved in axon guidance in the olfactory system as it is in other areas of the central nervous system (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2006b).

Given the continuous turnover of OSNs in the OE and the associated extension of axons into the OB, the environment has to be supportive for axonal regeneration. For that reason much attention has been directed to the properties of OECs, an olfactory pathway specific glial cell (Au et al., 2002). OECs promote axon growth when implanted in injured areas, and they express factors involved in migration, neurite extension and fasciculation (Bartolomei and Greer, 2000; Raisman, 2001). Nonetheless, it is still not clear how OECs are able to generate the permissive environment for the re-growing of axons. In mouse developing spinal cord there is an expression gradient of Wnt-4, and a source of Wnt-4 can attract growing axons. In the same model the absence of Fz-3 expression causes guidance defects (Lyuksyutova et al., 2003). In the olfactory system Wnt-4 is expressed in OECs, while Fz-3 can be found in OSN axons making it very temping to speculate that Wnt-4 is involved in the guidance of Fz-3 expressing axons. The persistence of Wnt-4 expression in adult OECs is consistent with the notion that a permissive or supportive environment is necessary for sustained OSN axonal growth.

Fz-7 expression has been associated with the proliferative/stem cell compartment during development and in the adult mouse gut epithelium (Gregorieff et al., 2005). Our observation of Fz-7 expression in unidentified cells in the basal portion of the OE, suggests an association with cells of the proliferating zone. Zaghetto et al. (2007) recently showed Fz-7 mRNA expression at the surface of the embryonic forebrain, along the trajectory of incoming OSN axons. We corroborated this result showing Fz-7 protein expression, and we have extended this observation by demonstrating that Fz-7 expression is associated with cells ensheathing the olfactory sensory neuron axon bundles and that this expression remains in the adult, although at lower levels. Wnt-5a, -8b, and -11, and perhaps other Wnt ligands, can interact with Fz-7 (Vincan et al., 2007); the signaling pathway activated depends on the presence of other Fz receptors, additional co-receptors, and downstream effectors. Therefore, Fz-7 activation can result in activation of the canonical as well as non-canonical pathways. Zaghetto et al. (2007), using a transgenic reporter strain of mice, identified Wnt-responsive cells, expressing βgal, located in the zone of Fz-7 expression in the embryonic forebrain. While in close apposition at E13, later in development βgal-expressing cells segregated from Fz-7+ cells into two different populations. Here, we found that Fz-7 persists in the adult, but we were not able to detect βgal+ cells. These data support the notion that the βgal-expressing cells and Fz-7+ cells seen during early development represent distinct populations that have different developmental fates. Because the βgal+ cells we identified also expressed BLBP, it seems reasonable to conclude that they are a subset of OECs. Although both the BAT-gal strain used by Zaghetto et al. (2007), and the TOPGAL strain we used show βgal expression after β-catenin stabilization, differences in mouse strains cannot be ruled out. Nonetheless, contrary to their observation we found in the TOPGAL mice βgal+ cells in the inner ONL in close association with the glomerular layer, as did a recent report from Booker-Dwyer et al. (2008). Differences in our findings with those of the Zaghetto report may be due to a discrepancy in classifying the boundaries between different layers in the OB.

Another interesting observation is the expression of Fz-7 in a subset of cells in the olfactory nerve that ensheath or surround the OECs expressing S100β and BLBP. The general structure of a nerve includes an endoneurium (separating the axons), a perineurium (sheaths axons fascicles) and an epineurium (sheaths several fascicles, the entire nerve and contains blood vessels). As S100β and BLBP expressing classical OECs sheath axon bundles, these cells would be part of the perineurium. Because the Fz-7-expressing cells wrap classical OECs they would be part of the perineurium. To the best of our knowledge this is the first time a marker for a second layer of sheath cells is described in the olfactory nerve.

Among Wnt molecules, Wnt-5a is one of the most extensively studied and has been implicated in multiple functions. We show that purified Wnt-5a added to OSN cultures increases neurite extension and alters growth cone morphology. Hippocampal neurons treated with Wnt-5a also showed an increase in axonal length, an effect that seems to be mediated by Dishevelled and an atypical PKC (Zhang et al., 2007). The signaling pathway Wnt-5a activates in OSNs is not yet known, but it would be interesting to analyze it as well as characterize the effect that knocking down Wnt-5a has on the olfactory system development.

In summary we present the first evidence of Wnt and Frizzled molecules playing a role in axonal extension in the olfactory system. The expression of Fz-1 and -3 and Wnt-5a in OSNs beginning with the earliest stages of olfactory epithelium development, and the expression of Fz-7 and Wnt-4 by OECs point to a fundamental role of Wnt and Fz molecules in olfactory system development. Moreover, the presence of specific subsets of adult glomeruli expressing Fz-1 suggests that this receptor could be one of the axon guidance molecules important for the formation and maintenance of topography between the olfactory epithelium and the olfactory bulb. Consistent with our spatial and temporal localizations, we further showed that Wnt-5a increases OSNs axonal extension, alters growth cone morphology, and that a subset of OECs is Wnt-responsive during the formation of the primary olfactory pathway. Further characterization of other Wnt and Fz members as well as their role remains to be done, but the present work opens up a new field in understanding the complexity of the olfactory system formation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DC00210, DC006972, DC006291, and AG028054 (C.A.G.). We thank Dr. Qizhi Gong for the generous gift of the chicken anti-OMP, Dolores Montoya for technical assistance, Fumiaki Imamura, Lorena Rela, Helen Treloar, Mary Whitman and Alexandra Miller for critical reading of this manuscript, and all members of the laboratory for ongoing discussions and advice.

References

- Akins MR, Benson DL, Greer CA. Cadherin expression in the developing mouse olfactory system. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501(4):483–497. doi: 10.1002/cne.21270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins MR, Greer CA. Axon behavior in the olfactory nerve reflects the involvement of catenin-cadherin mediated adhesion. J Comp Neurol. 2006a;499(6):979–989. doi: 10.1002/cne.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins MR, Greer CA. Cytoskeletal organization of the developing mouse olfactory nerve layer. J Comp Neurol. 2006b;494(2):358–367. doi: 10.1002/cne.20814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astic L, Pellier-Monnin V, Saucier D, Charrier C, Mehlen P. Expression of netrin-1 and netrin-1 receptor, DCC, in the rat olfactory nerve pathway during development and axonal regeneration. Neuroscience. 2002;109(4):643–656. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au WW, Treloar HB, Greer CA. Sublaminar organization of the mouse olfactory bulb nerve layer. J Comp Neurol. 2002;446(1):68–80. doi: 10.1002/cne.10182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei JC, Greer CA. Olfactory ensheathing cells: bridging the gap in spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(5):1057–1069. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker-Dwyer T, Hirsh S, Zhao H. A unique cell population in the mouse olfactory bulb displays nuclear beta-catenin signaling during development and olfactory sensory neuron regeneration. Dev Neurobiol. 2008 doi: 10.1002/dneu.20606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carron C, Pascal A, Djiane A, Boucaut JC, Shi DL, Umbhauer M. Frizzled receptor dimerization is sufficient to activate the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 12):2541–2550. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson C, Murdoch B, Roskams AJ. Notch 2 and Notch 1/3 segregate to neuronal and glial lineages of the developing olfactory epithelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235(6):1678–1688. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler AT, Zou DJ, Le Pichon CE, Peterlin ZA, Matthews GA, Pei X, Miller MC, Firestein S. A G protein/cAMP signal cascade is required for axonal convergence into olfactory glomeruli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(3):1039–1044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609215104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chess A, Simon I, Cedar H, Axel R. Allelic inactivation regulates olfactory receptor gene expression. Cell. 1994;78(5):823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90562-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Col JA, Matsuo T, Storm DR, Rodriguez I. Adenylyl cyclase-dependent axonal targeting in the olfactory system. Development. 2007;134(13):2481–2489. doi: 10.1242/dev.006346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce JC, McClay DR. The canonical Wnt pathway in embryonic axis polarity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17(2):168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutforth T, Moring L, Mendelsohn M, Nemes A, Shah NM, Kim MM, Frisen J, Axel R. Axonal ephrin-As and odorant receptors: coordinate determination of the olfactory sensory map. Cell. 2003;114(3):311–322. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126(20):4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlos JA, Lopez-Mascaraque L, Valverde F. The telencephalic vesicles are innervated by olfactory placode-derived cells: a possible mechanism to induce neocortical development. Neuroscience. 1995;68(4):1167–1178. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00199-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein P, Mombaerts P. A contextual model for axonal sorting into glomeruli in the mouse olfactory system. Cell. 2004;117(6):817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Q, Shipley MT. Evidence that pioneer olfactory axons regulate telencephalon cell cycle kinetics to induce the formation of the olfactory bulb. Neuron. 1995;14(1):91–101. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorieff A, Pinto D, Begthel H, Destree O, Kielman M, Clevers H. Expression pattern of Wnt signaling components in the adult intestine. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):626–638. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guder C, Philipp I, Lengfeld T, Watanabe H, Hobmayer B, Holstein TW. The Wnt code: cnidarians signal the way. Oncogene. 2006;25(57):7450–7460. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds JW, Hinds PL. Synapse formation in the mouse olfactory bulb. I. Quantitative studies. J Comp Neurol. 1976;169(1):15–40. doi: 10.1002/cne.901690103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Suzuki M, Sakano H. Odorant receptor-derived cAMP signals direct axonal targeting. Science. 2006;314(5799):657–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1131794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafitz KW, Greer CA. Role of laminin in axonal extension from olfactory receptor cells. J Neurobiol. 1997;32(3):298–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko-Goto T, Yoshihara S, Miyazaki H, Yoshihara Y. BIG-2 mediates olfactory axon convergence to target glomeruli. Neuron. 2008;57(6):834–846. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaykas A, Yang-Snyder J, Heroux M, Shah KV, Bouvier M, Moon RT. Mutant Frizzled 4 associated with vitreoretinopathy traps wild-type Frizzled in the endoplasmic reticulum by oligomerization. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(1):52–58. doi: 10.1038/ncb1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeble TR, Halford MM, Seaman C, Kee N, Macheda M, Anderson RB, Stacker SA, Cooper HM. The Wnt receptor Ryk is required for Wnt5a-mediated axon guidance on the contralateral side of the corpus callosum. J Neurosci. 2006;26(21):5840–5848. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1175-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb BW, Treloar HB, Klenoff J, Greer CA. Cell surface carbohydrates and glomerular targeting of olfactory sensory neuron axons in the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467(1):22–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.10910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyuksyutova AI, Lu CC, Milanesio N, King LA, Guo N, Wang Y, Nathans J, Tessier-Lavigne M, Zou Y. Anterior-posterior guidance of commissural axons by Wnt-frizzled signaling. Science. 2003;302(5652):1984–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.1089610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretto S, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Braghetta P, Broccoli V, Hassan AB, Volpin D, Bressan GM, Piccolo S. Mapping Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during mouse development and in colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(6):3299–3304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marillat V, Cases O, Nguyen-Ba-Charvet KT, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sotelo C, Chedotal A. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of slit and robo genes in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2002;442(2):130–155. doi: 10.1002/cne.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamichi K, Serizawa S, Kimura HM, Sakano H. Continuous and overlapping expression domains of odorant receptor genes in the olfactory epithelium determine the dorsal/ventral positioning of glomeruli in the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2005;25(14):3586–3592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0324-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P. Axonal wiring in the mouse olfactory system. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:713–737. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012804.093915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P, Wang F, Dulac C, Vassar R, Chao SK, Nemes A, Mendelsohn M, Edmondson J, Axel R. The molecular biology of olfactory perception. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:135–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisman G. Olfactory ensheathing cells - another miracle cure for spinal cord injury? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(5):369–375. doi: 10.1038/35072576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Sullivan SL, Buck LB. A zonal organization of odorant receptor gene expression in the olfactory epithelium. Cell. 1993;73(3):597–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90145-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Mimmack M, Kishimoto J, Keverne EB, Emson PC. Expression of olfactory receptors, G-proteins and AxCAMs during the development and maturation of olfactory sensory neurons in the mouse. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;110(1):69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas PC. Retrograde signalling at the synapse: a role for Wnt proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 6):1295–1298. doi: 10.1042/BST0331295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte G, Bryja V, Rawal N, Castelo-Branco G, Sousa KM, Arenas E. Purified Wnt-5a increases differentiation of midbrain dopaminergic cells and dishevelled phosphorylation. J Neurochem. 2005;92(6):1550–1553. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Pfaff DW. Origin of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Nature. 1989;338(6211):161–164. doi: 10.1038/338161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbacher K, Fleischer J, Breer H. Odorant receptor proteins in olfactory axons and in cells of the cribriform mesenchyme may contribute to fasciculation and sorting of nerve fibers. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;323(2):211–219. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa S, Miyamichi K, Nakatani H, Suzuki M, Saito M, Yoshihara Y, Sakano H. Negative feedback regulation ensures the one receptor-one olfactory neuron rule in mouse. Science. 2003;302(5653):2088–2094. doi: 10.1126/science.1089122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa S, Miyamichi K, Takeuchi H, Yamagishi Y, Suzuki M, Sakano H. A neuronal identity code for the odorant receptor-specific and activity-dependent axon sorting. Cell. 2006;127(5):1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John JA, Claxton C, Robinson MW, Yamamoto F, Domino SE, Key B. Genetic manipulation of blood group carbohydrates alters development and pathfinding of primary sensory axons of the olfactory systems. Dev Biol. 2006;298(2):470–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John JA, Pasquale EB, Key B. EphA receptors and ephrin-A ligands exhibit highly regulated spatial and temporal expression patterns in the developing olfactory system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;138(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struewing IT, Barnett CD, Zhang W, Yadav S, Mao CD. Frizzled-7 turnover at the plasma membrane is regulated by cell density and the Ca(2+) -dependent protease calpain-1. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313(16):3526–3541. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam PP, Loebel DA, Tanaka SS. Building the mouse gastrula: signals, asymmetry and lineages. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16(4):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiler K. The House Mouse: Development and Normal Stages from Fertilization to 4 Weeks of Age. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg, New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Treloar HB, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Greer CA. Specificity of glomerular targeting by olfactory sensory axons. J Neurosci. 2002;22(7):2469–2477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02469.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincan E, Swain RK, Brabletz T, Steinbeisser H. Frizzled7 dictates embryonic morphogenesis: implications for colorectal cancer progression. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4558–4567. doi: 10.2741/2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Guo N, Nathans J. The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006a;26(8):2147–2156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4698-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Thekdi N, Smallwood PM, Macke JP, Nathans J. Frizzled-3 is required for the development of major fiber tracts in the rostral CNS. J Neurosci. 2002;22(19):8563–8573. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08563.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang J, Mori S, Nathans J. Axonal growth and guidance defects in Frizzled3 knock-out mice: a comparison of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging, neurofilament staining, and genetically directed cell labeling. J Neurosci. 2006b;26(2):355–364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3221-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Shu W, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Wnt7b activates canonical signaling in epithelial and vascular smooth muscle cells through interactions with Fzd1, Fzd10, and LRP5. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(12):5022–5030. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5022-5030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Re-solving the cadherin-catenin-actin conundrum. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(47):35593–35597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600027200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Hogarth LC, Puche AC, Torrey C, Cai X, Song I, Kolodkin AL, Shipley MT, Ronnett GV. Expression of semaphorins in developing and regenerating olfactory epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 2000;423(4):565–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaghetto AA, Paina S, Mantero S, Platonova N, Peretto P, Bovetti S, Puche A, Piccolo S, Merlo GR. Activation of the Wnt-beta catenin pathway in a cell population on the surface of the forebrain is essential for the establishment of olfactory axon connections. J Neurosci. 2007;27(36):9757–9768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0763-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhu J, Yang GY, Wang QJ, Qian L, Chen YM, Chen F, Tao Y, Hu HS, Wang T, Luo ZG. Dishevelled promotes axon differentiation by regulating atypical protein kinase C. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(7):743–754. doi: 10.1038/ncb1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou DJ, Chesler AT, Le Pichon CE, Kuznetsov A, Pei X, Hwang EL, Firestein S. Absence of adenylyl cyclase 3 perturbs peripheral olfactory projections in mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27(25):6675–6683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0699-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.