Abstract

Detergent-insoluble complexes prepared from pig small intestine are highly enriched in several transmembrane brush border enzymes including aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase, indicating that they reside in a glycolipid-rich environment in vivo. In the present work galectin-4, an animal lectin lacking a N-terminal signal peptide for membrane translocation, was discovered in these complexes as well, and in gradient centrifugation brush border enzymes and galectin-4 formed distinct soluble high molecular weight clusters. Immunoperoxidase cytochemistry and immunogold electron microscopy showed that galectin-4 is indeed an intestinal brush border protein; we also localized galectin-4 throughout the cell, mainly associated with membraneous structures, including small vesicles, and to the rootlets of microvillar actin filaments. This was confirmed by subcellular fractionation, showing about half the amount of galectin-4 to be in the microvillar fraction, the rest being associated with insoluble intracellular structures. A direct association between the lectin and aminopeptidase N was evidenced by a colocalization along microvilli in double immunogold labeling and by the ability of an antibody to galectin-4 to coimmunoprecipitate aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase. Furthermore, galectin-4 was released from microvillar, right-side-out vesicles as well as from mucosal explants by a brief wash with 100 mM lactose, confirming its extracellular localization. Galectin-4 is therefore secreted by a nonclassical pathway, and the brush border enzymes represent a novel class of natural ligands for a member of the galectin family. Newly synthesized galectin-4 is rapidly “trapped” by association with intracellular structures prior to its apical secretion, but once externalized, association with brush border enzymes prevents it from being released from the enterocyte into the intestinal lumen.

INTRODUCTION

The brush border enzymes of the small intestinal enterocyte provide a good model for studying membrane polarity in an epithelium in situ. They include a large number of hydrolases, notably peptidases and glycosidases, that are constitutively made by the enterocyte to maintain a high digestive capacity of its apical brush border in the proteolytic environment of the intestinal lumen (Semenza, 1986; Alpers, 1987). We have previously observed that several of the transmembrane brush border enzymes, including aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase, are among the major protein components of detergent-insoluble complexes prepared from enterocyte membranes, indicating that they reside in glycolipid microdomains in vivo (Danielsen, 1995). Radioactive labeling experiments showed that newly synthesized brush border enzymes integrate into these structures before appearing at the cell surface, indicating that transmembrane as well as glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins may be transported by the “raft” mechanism (Brown and Rose, 1992; Fiedler et al., 1993). We also recently described the presence of melanotransferrin, a 80-kDa GPI-anchored member of the transferrin family of iron-binding proteins, in glycolipid microdomains prepared from fetal enterocytes (Danielsen and van Deurs, 1995). By immunogold electron microscopy, melanotransferrin was localized to apical microdomain patches between adjacent microvilli that bore no morphological resemblance to caveolae.

In the present work, galectin-4 was identified as a major component of detergent-insoluble complexes prepared from the small intestine. The galectin family of β-galactoside-binding proteins (also known as S-type lectins) is a class of vertebrate lectins, and members of the family have been found in a variety of tissues and cell types and have been implicated in processes as diverse as embryonic and tumor development, connective tissue regulation, organization of the nervous system and immune regulation (Harrison, 1991; Drickamer and Taylor, 1993; Barondes et al., 1994). Lacking a signal peptide for membrane translocation, galectins are considered to be cytosolic proteins, but some of the members, in particular galectin-1 and galectin-3, have been localized in the extracellular matrix. To account for this, galectins have been proposed to be secreted by a nonclassical pathway (Cooper and Barondes, 1990; Muesch et al., 1990). Despite the abundancy of extracellular β-galactoside-containing glycoconjugates, only a few have been shown to act as natural ligands for galectins; thus laminin, integrin α7β1, IgE, and the IgE receptor are among the few binding partners so far identified (Barondes et al., 1994). Our present results indicate that galectin-4 in the enterocyte is secreted apically by a nonclassical mechanism. Once externalized, the lectin remains at the cell surface, forming clusters with brush border enzymes, in particular aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Equipment for performing organ culture, including Trowell’s T-8 medium and culture dishes with grids, was obtained as previously described (Danielsen et al., 1982). Monoclonal antibodies to human annexin II were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY), and peroxidase-conjugated swine immunoglobulins to rabbit immunoglobulins and peroxidase-conjugated rabbit immunoglobulins to mouse immunoglobulins were from DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark).

A rabbit antibody to pig intestinal aminopeptidase N was used as previously described (Hansen et al., 1992), and protein A-gold (PAG) was obtained from Dr. J. W. Slot and Dr. G. Posthuma (Utrecht University, School of Medicine, The Netherlands). Pig small intestine was kindly provided by the Department of Experimental Medicine, The Panum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Organ Culture of Mucosal Explants and Tissue Fractionation

Radioactive labeling of jejunal mucosal explants in organ culture and subcellular fractionation of labeled explants into a Mg2+-precipitated fraction (intracellular and basolateral membranes) and a microvillar fraction was performed by the method of Booth and Kenny (1974) as previously described (Danielsen, 1982), with MgCl2 instead of CaCl2. Detergent-insoluble complexes (glycolipid microdomains) were isolated from microvillar membranes by the method of Brown and Rose (1992) as previously described (Danielsen, 1995).

Preparation of an Antibody to Galectin-4

Starting with about 200 g of everted, washed, and frozen pig small intestine, a microvillar fraction was prepared from a mucosal homogenate, and the microvilli were resuspended in 10 mM imidazole hydrochloride, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM NaN3, pH 7.4, and solubilized by extraction with 1% Triton X-100 (10 min at 37°C). The demembranated microvilli were washed in the same buffer and then resuspended and extracted with 10 mM imidazole hydrochloride, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM NaN3, and 5 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, pH 7.4. The extract was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 1 h, and the supernatant was dialyzed extensively against 10 mM imidazole hydrochloride, 0.5 mM DTT, and 1 mM NaN3, pH 7.4, and passed through a column of DE-52 cellulose. The pass-through was collected and precipitated by addition of ammonium sulfate (70% saturation). The resulting protein pellet was resolubilized in a small volume of 25 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES) and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, mixed with an equal volume of Freund’s incomplete adjuvant, and injected intracutaneously into a rabbit (about 50 μg/injection) at 2-week intervals. The rabbit was bled a week after the fourth injection. Booster injections were given at 6-week intervals, followed by new bleedings. The immunoglobulin fraction was isolated from the antiserum by chromatography on a column of protein A-Sepharose.

Morphological Investigations

Light Microscopy.

Aldehyde-fixed tissue (pig small intestine, pancreas, and liver) was embedded in paraffin. Deparafinated sections were treated with methanol-H2O2, then with goat serum, and finally incubated overnight at 4°C with the rabbit anti-pig galectin-4 antibody. After washing the sections were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG, followed by washing, incubating in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in H2O2, and finally staining with hematoxylin.

Electron Microscopy.

Pieces of pig small intestine were fixed overnight by immersion in 0.1% glutaraldehyde and 2% formaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2. After fixation, the specimens were buffer-washed, infiltrated with sucrose, mounted on stubs, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ultracryosections were single-labeled with rabbit anti-pig galectin-4 followed by PAG or double-labeled with the anti-galectin-4 antibody followed by rabbit anti-aminopeptidase N and PAG. Finally, the sections were inspected in a Philips 100 CM electron microscope.

Velocity Sedimentation Analysis

Samples (1 ml) of total mucosal membrane fractions in 25 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, were extracted for 10 min at 37°C with 20 mM 3-[(3-chloramidopropyl)demethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) and 1 mM EDTA, then layered on top of a 10–30% sucrose gradient (made up in 12 ml of the above buffer containing 2 mM CHAPS), and centrifuged in a SW 40 Ti rotor (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA) for 18 to 20 h at 3°C at 28,000 rpm (gav = 97,400). After centrifugation, the gradients were fractionated into samples of 1 ml and a pellet.

Electrophoretic Methods

SDS-PAGE in 10% gels under reducing conditions was performed according to Laemmli (1970). For Western blotting, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were electrotransferred onto Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and visualized by the procedure of Bjerrum et al. (1983). When the same membrane was blotted successively with different antibodies, it was washed with methanol for 5 min in between the incubations with antibodies. Quantitative rocket immunoelectrophoresis in 1% agarose gels was performed essentially as described by Weeke (1973).

Amino Acid Sequence Determination

For identification of galectin-4, the 36-kDa protein, electroblotted onto Immobilon, was excised from gel tracks 11–13 of an experiment performed as shown in Figure 1, which effectively separates the lectin from annexin II, another microvillar protein of 36 kDa. Generation of proteolytic peptides, their isolation by high-pressure liquid chromatography, and amino acid sequencing was performed by Innovagen AB (Lund, Sweden).

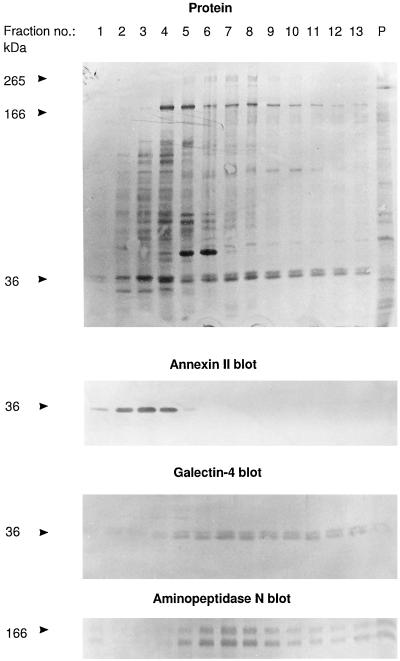

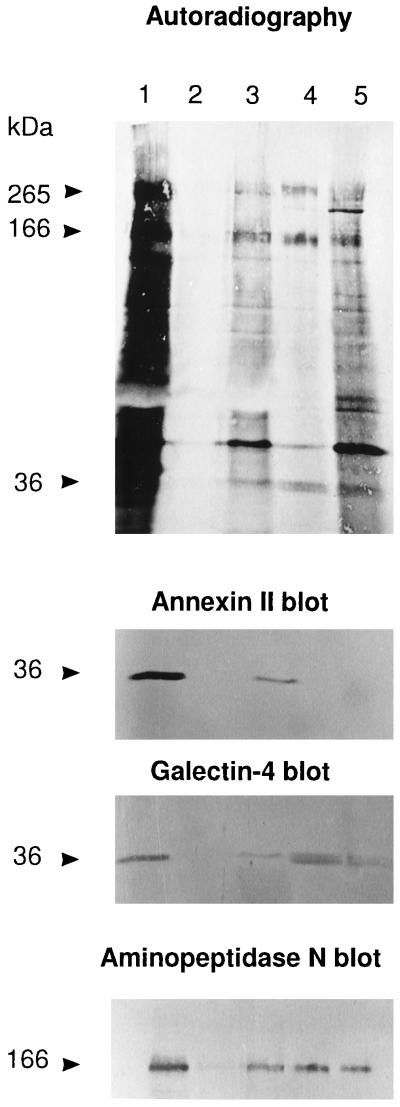

Figure 1.

Identification of galectin-4 as a 36-kDa protein present in high molecular weight clusters. Intestinal mucosa was homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer in ice-cold 25 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, containing 10 μg/ml aprotinin and 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting pellet of total membranes was resuspended in the above buffer and solubilized by extraction at 37°C for 10 min with 20 mM CHAPS and 1 mM EDTA. One milliliter of the extract was analyzed by velocity sedimentation in a sucrose gradient as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. After centrifugation, 0.25 ml of each fraction was mixed with an equal volume of acetone, and after 15 min on ice, protein was pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, using the primary antibodies indicated. Lanes 1 and 13 represent the top and bottom fractions of the gradient, respectively, and lane P shows the proteins recovered from the pellet of the centrifugation. Total protein was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Both the 166-kDa band of aminopeptidase N and its B-subunit, which is formed by proteolytic cleavage in vivo (Sjöström et al., 1978) are shown at the bottom. Molecular mass values are indicated.

RESULTS

Identification of Galectin-4 in High Molecular Weight Clusters and Detergent-insoluble Complexes

Figure 1 shows an analysis of a total mucosal membrane fraction (after extraction with detergent at 37°C which readily solubilizes glycolipid microdomains; Brown and Rose, 1992) by velocity sedimentation through a 10–30% sucrose gradient in the presence of detergent. Notice that the bulk of the proteins appeared in fractions 2–6, but only a relatively small number of components sedimented near the bottom of the gradient (fractions 9–13). Some of the aminopeptidase N was seen in fractions 5–7, indicating its presence as a homodimer, but a significant proportion sedimented in fractions 9–13 with some other prominent brush border enzymes, including sucrase-isomaltase, maltase-glucoamylase, and aminopeptidase A but not lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (Figure 2). However, the most abundant component in the bottom fractions of the gradient was a doublet of 36 kDa. Subsequent amino acid sequencing of proteolytic peptides of the 36-kDa protein gave the two following sequences: VGSSGDVALHINPRLTEGI and SSFNPFAPGQYFDLSIRCGLDRFK. In a database search (BLAST, National Center for Biotechnology Information), these sequences matched 100% with amino acids 227–245 and 263–286, respectively, of a 35.8-kDa lactose-binding protein from pig intestine, termed galectin-4 (lectin L-36; Chiu et al., 1994). The only other database proteins producing high-scoring segment pairs in the search included rat galectin-4 and, to a lesser extent, other members of the galectin family of lectins.

Figure 2.

Brush border enzymes in high molecular weight clusters. Rocket immunoelectrophoresis against antibodies to aminopeptidase N, sucrase-isomaltase, maltase-glucoamylase, aminopeptidase A, and lactase-phlorizin hydrolase of gradient fractions from top to bottom of the experiment shown in Figure 1. Twenty microliters of each fraction was applied to the wells and after electrophoresis, the immunoprecipitates were visualized by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue.

In one experiment, fractions 4 and 5 from a sucrose gradient similar to that shown in Figure 1 were frozen and thawed, dialyzed overnight against gradient buffer, centrifuged again on a second sucrose gradient, and finally analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Fractions 10 and 11 from the same gradient were treated likewise. All proteins in fractions 4 and 5 of the first gradient appeared exclusively in fractions 2–6 of the second gradient, indicating that the high molecular weight clusters do not form as a preparational artefact during or before the centrifugation (our unpublished results). In contrast, proteins from fractions 10 and 11 of the first gradient were only partly recovered at the bottom fractions of the second gradient; some bands appeared in fractions 2–6 as well (our unpublished results), indicating that the high molecular weight complexes are sensitive to a freeze/thaw or simply unstable in solution.

Figure 3 shows an experiment similar to the velocity sedimentation analysis of Figure 1 except that the membranes were detergent-extracted in the presence of 100 mM lactose prior to the gradient centrifugation. Galectin-4 now almost exclusively sedimented in the top fractions of the gradient, showing that the clustering of galectin-4 is mediated by lectin–carbohydrate interactions. In contrast, the position of aminopeptidase N in the bottom fractions was unaffected. In fact, the only ligands present in the bottom fractions in sufficient amounts to account for the observed clustering of galectin-4 (in the absence of lactose) are the brush border enzymes, in particular aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase. The above experiments therefore suggest that brush border enzymes may serve as natural ligands for galectin-4. The lactose-resistant clustering of aminopeptidase N may be due to association with the microvillar cytoskeleton because the 42-kDa band of actin was also present in the bottom fractions of the gradient.

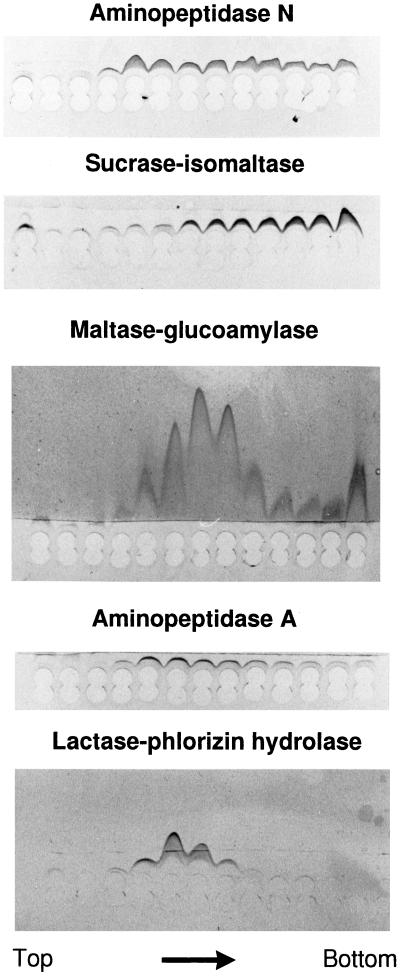

Figure 3.

Lactose releases galectin-4 from high molecular weight clusters. An experiment similar to that shown in Figure 1 except that the membranes were detergent extracted in the presence of 100 mM lactose and that lactose (10 mM) was present in the sucrose gradient. After SDS-PAGE and electrotransfer onto Immobilon, the bands of galectin-4 and aminopeptidase N were visualized by Western blotting. Molecular mass values are indicated.

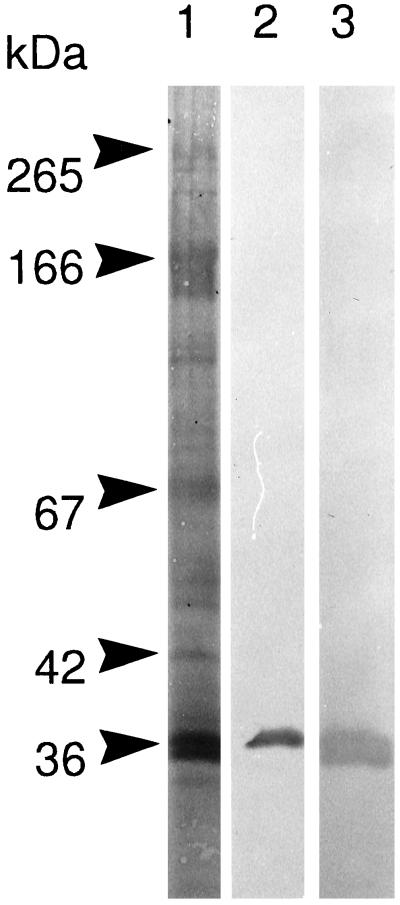

In a previous work, detergent-insoluble complexes prepared from small intestinal mucosa were observed to have a very distinct protein composition and to be heavily enriched in brush border enzymes such as the transmembrane sucrase-isomaltase and aminopeptidase N, as well as the GPI-anchored alkaline phosphatase (Danielsen, 1995). These proteins thus were an estimated 25–30% of the total protein in the glycolipid microdomains, and the only major protein band not identified in this fraction was one of 36 kDa. An antibody raised to galectin-4 showed the lectin to be a prominent component of detergent-insoluble complexes (Figure 4). Contrary to aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase, which are only partially low-temperature detergent-insoluble (Danielsen, 1995), galectin-4 completely resists detergent solubilization at 0°C (Figure 5, lane 2). Annexin II (a microvillar protein of similar molecular weight) is also present in these complexes, but unlike galectin-4, the 36-kDa band of annexin II migrated exclusively in the top fractions of the sucrose gradient (Figure 1, compare annexin II and galectin-4 blots). Galectin-4 is not expressed in the kidney (Oda et al., 1993), and unlike the annexin II antibody, the antibody to galectin-4 failed to detect a 36-kDa band in detergent-insoluble complexes prepared from a total membrane extract of pig kidney (our unpublished results). Importantly, this confirms that the latter antibody only recognizes galectin-4 but not annexin II.

Figure 4.

Galectin-4 is a major component of glycolipid microdomains. SDS-PAGE of Triton X-100-insoluble complexes prepared from a microvillar fraction. After electrophoresis and electrotransfer onto an Immobilon membrane, the gel tracks were either stained for protein with Coomassie brilliant blue (lane 1) or Western blotted, using a monoclonal antibody to annexin II (lane 2) or a polyclonal antibody to galectin-4 prepared as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS (lane 3). Notice that the galectin-4 antibody only reacted with the 36-kDa band and not the 265- and 166-kDa bands of sucrase-isomaltase and aminopeptidase N, respectively. Molecular mass values are indicated.

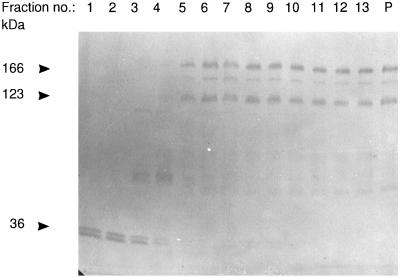

Figure 5.

Copurification of galectin-4 and brush border enzymes. A mucosal explant, labeled for 2 h with 0.5 mCi/ml [35S]methionine, was homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer in 1 ml of 25 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, containing 10 μg/ml aprotinin and 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was centrifuged for 48,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting pellet of total membranes was resuspended in 0.25 ml of HEPES buffer and solubilized for 10 min on ice by the addition of CHAPS (20 mM). The extract was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min to obtain a supernant of low temperature detergent-soluble protein and a pellet. The pellet was resuspended in 0.25 ml HEPES buffer and solubilized for 10 min at 37°C by 20 mM CHAPS and 1 mM EDTA. The extract was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min to obtain a supernatant of (solubilized) low-temperature detergent-insoluble protein and a pellet. Galectin-4 antibody (0.2 ml) was added to both the extracts of low-temperature detergent-soluble and low-temperature detergent-insoluble proteins, and after incubation at 4°C overnight, the extracts were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min to pellet the immunoprecipitates. The immunoprecipitates of both the low-temperature detergent-soluble (lane 2) and low-temperature detergent-insoluble (lane 4) fractions were washed in buffer once and analyzed by SDS-PAGE together with 100 μl of the corresponding extract supernatants left after immunoprecipitation (lanes 1 and 3, respectively) and the pellet of detergent-insoluble material (lane 5). After electrophoresis and electrotransfer onto an Immobilon membrane, the gel tracks were visualized by autoradiography, and then Western blotted in three successive steps using the indicated primary antibodies. (The single sharp 36-kDa band seen in lanes 1 and 3 of the galectin-4 blot is residual staining of annexin II from the previous round of blotting because they were not observed in single blot experiments using the galectin-4 antibody alone). Molecular mass values are indicated.

Copurification of Brush Border Enzymes and Galectin-4

Figure 5 shows that the polyclonal galectin-4 antibody failed to detect the lectin in the low-temperature detergent-soluble fraction (Figure 5, lane 2) but was able to immunoprecipitate the lectin from the low-temperature detergent-insoluble fraction (Figure 5, lane 4) of [35S]methionine-labeled mucosal explants after a second extraction with detergent at 37°C, which completely solubilizes both transmembrane and GPI-anchored proteins from glycolipid rafts (Brown and Rose, 1992; Danielsen, 1995). Interestingly, the 265- and 166-kDa bands of sucrase-isomaltase and aminopeptidase N from the latter fraction were partially coprecipitated by the galectin-4 antibody (the 42-kDa band of actin was seen as well). In contrast, the two brush border enzymes were not immunoprecipitated from the corresponding low-temperature detergent-soluble fraction from which galectin-4 is absent but which contains a large proportion of the brush border enzymes (Figure 5, compare lanes 2 and 4). Thus, the coprecipitation of sucrase-isomaltase and aminopeptidase N is not due to artefactual cross-reactivity with the antibody but must be due to their association with galectin-4 present in the low-temperature detergent-insoluble fraction. The anti-annexin II monoclonal antibody visualized this protein only in the supernatants collected after the immunoprecipitates had been pelleted by centrifugation (Figure 5, lanes 1 and 3), showing that annexin II and galectin-4 are not associated. This experiment thus confirms that the brush border enzymes and galectin-4 to a significant extent are associated, as suggested by the lactose-sensitive clustering observed by gradient centrifugation analysis.

Localization of Galectin-4

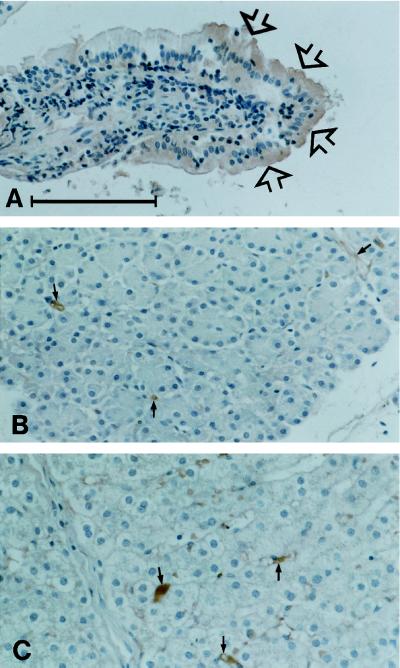

Figure 6 shows the distribution of galectin-4 in three different epithelial tissues by immunoperoxidase cytochemistry. In the enterocytes, a clear reaction was seen in the cytosol and, more intensely, in the brush border membrane, in particular in cells toward the tip of the villi. In contrast, epithelial cells of the liver and pancreas were unlabeled.

Figure 6.

Distribution of galectin-4 in a pig small intestinal villus (A), pancreas (B), and liver (C). Note that the enterocytes, in particular those at the tip of the villus (arrows in A) are clearly labeled. In the two other tissues the epithelial paranchyma is unstained although some immunoperoxidase staining may be seen in relation to stromal elements (small arrows). Bar, 100 μm.

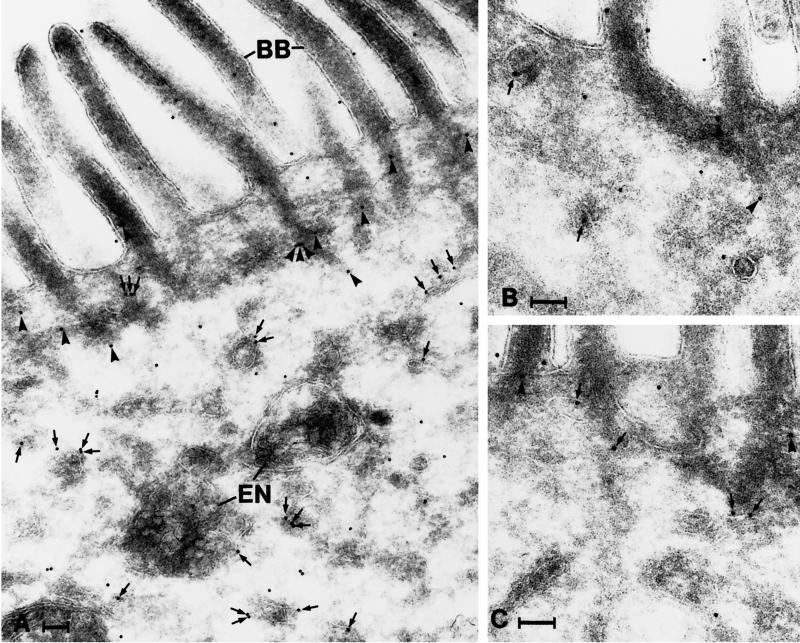

Immunogold labeling of ultracryosections revealed that galectin-4 is present throughout the cytosol of the enterocytes (Figure 7). Interestingly, the labeling did not appear to be randomly distributed in the cytoplasm because gold particles were often seen in association with various tubulo-vesicular structures, in particular on their cytoplasmic surface. In addition, the bundles of actin filaments descending from the microvilli into the apical terminal web often appeared labeled. Finally, the brush border itself was labeled; some labeling was associated with the cytoskeletal core and some was associated the the lipid membrane (Figure 7). Galectin-4 labeling was never seen in the Golgi complex/trans-Golgi network and only very rarely in endosome/lysosome-like structures. Because the apical portion of the enterocyte is of particular interest in relation to brush border enzymes, we quantified the galectin-4 labeling of the most apical 3.5 μm of the enterocytes; this revealed that 29% of the galectin-4 (gold particles) were localized to tubulo-vesicular structures (more than two-thirds on their cytoplasmic surface), 46% were found over the brush border and microvillar actin filament rootlets, and only 25% of the gold particles appeared unassociated with any recognizable structure (total number of gold particles counted, 835). The latter number is probably an overestimate because, as described below, galectin-4 is essentially absent from the soluble pool of proteins.

Figure 7.

Distribution of galectin-4 in the apical portion of enterocytes as revealed by immunogold labeling. Gold particles are seen throughout the cytoplasm, in association with tubulo-vesicular structures (arrows) and the actin rootlets of microvilli (arrowheads). Note that many of the gold particles associated with tubulo-vesicular structures are found on their cytosolic surface. BB, brush border; En, endosomes. Bar, 100 nm.

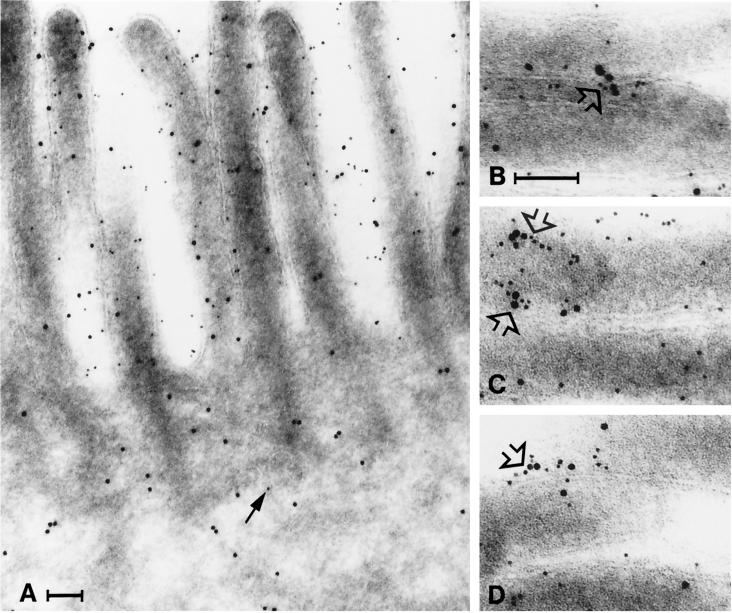

Double immunogold labeling showed that aminopeptidase N, in contrast to galectin-4, was almost exclusively localized to the brush border (Figure 8). Moreover, the double labeling revealed that the two proteins sometimes form distinct aggregates at the microvillar membrane, confirming their clustering in density gradient centrifugation and in immunopurification.

Figure 8.

Clustering of galectin-4 and aminopeptidase N. Immunogold double labeling for aminopeptidase N (5-nm gold) and galectin-4 (10-nm gold). (A) Aminopeptidase N and galectin-4 are present in the brush border, but little aminopeptidase N is seen in the cytoplasm (arrow). (B–D) Galectin-4 and aminopeptidase N often form clusters in the microvillar membrane (open arrows). Bars, 100 nm.

Galectin-4 Is an Apically Secreted Brush Border Protein

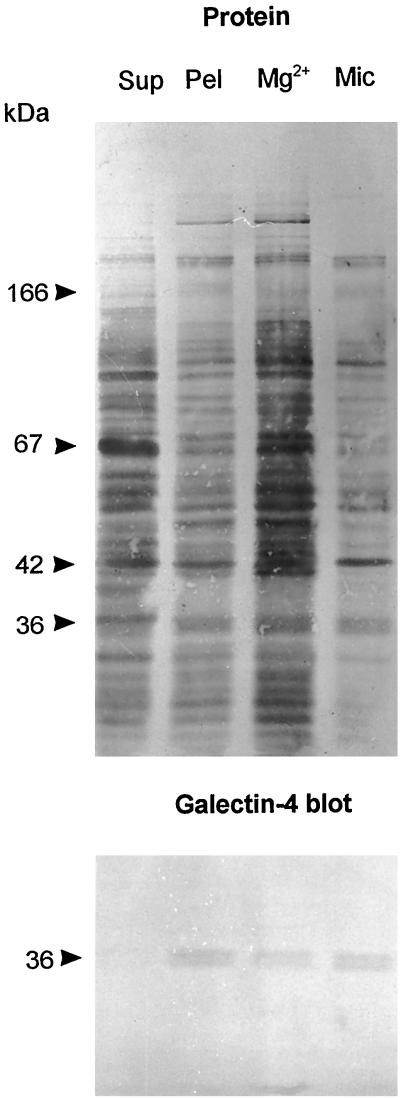

In subcellular fractionation, essentially all galectin-4 in a mucosal homogenate was pelleted by centrifugation at 48,000 × g for 30 min, indicating that most if not all of the lectin in the enterocyte is associated with either cytoskeletal or membraneous structures (Figure 9). This figure also shows that at least half the amount of galectin-4 is present in the microvillar fraction rather than in the bulky Mg2+-precipitated fraction. Because the microvillar fraction only contains about 10% of the total homogenate protein (Sjöström et al., 1978), galectin-4 is considerably enriched (about 5 times) in the brush border membrane relative to the homogenate. By comparison, brush border enzymes are typically enriched 8–10 times by this type of fractionation. The localization of galectin-4 both by immunogold electron microscopy shown above thus agrees well with the distribution of the lectin studied by subcellular fractionation.

Figure 9.

Subcellular distribution of galectin-4. About 1 g of frozen intestinal mucosa was thawed and homogenized in a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer in 10 ml of 25 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0. The homogenate was cleared by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min and then centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 30 min, to obtain a pellet (Pel) and a supernatant (Sup). The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of the above buffer and 50 μl of this fraction and of the supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Likewise, from 1 g of intestinal mucosa, Mg2+-precipitated (Mg2+) and microvillar (Mic) fractions were prepared and resuspended in equal volumes of 25 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, and samples of 50 μl were examined by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gel tracks were Western blotted with the galectin-4 antibody and afterward stained for protein with Coomassie brilliant blue.

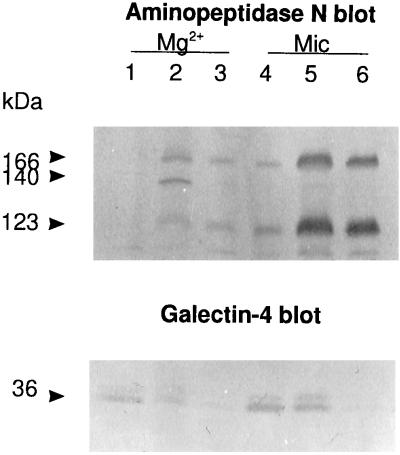

To decide whether the lectin was present on the cytosolic or extracellular side of the brush border surface (a difficult decision to make based solely on gold-labeled cryosections), a microvillar fraction, containing predominantly, if not exclusively, tight right-side-out vesicles (Booth and Kenny, 1976), was washed briefly with 100 mM lactose (10 min on ice) in the absence of detergent. As shown in Figure 10, this treatment released about half the amount of galectin-4 and only neglegible amounts of aminopeptidase N from the vesicles. When detergent was included in a second extraction, the remaining membrane-associated galectin-4 was released, as was a major fraction of aminopeptidase N. The experiment thus shows that a major proportion of the lectin is present at the extracellular side of the microvillar membrane, thereby implying that it has been secreted from the enterocyte. A brief wash with lactose also released the bulk of galectin-4 from the Mg2+-precipitated fraction (Figure 10). As described above, galectin-4 is essentially absent from the pool of soluble proteins and in the cytoplasm it appears in immunogold electron microscopy to be largely associated with membraneous structures, small vesicles, and cytoskeletal filaments; ligand binding thus releases the lectin from these structures.

Figure 10.

Galectin-4 is present on the extracellular side of mivrovillar vesicles. Mg2+-precipitated (Mg2+) and microvillar (Mic) membranes were resuspended in 25 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM lactose and incubated for 10 min on ice. After centrifugation at 48,000 × g for 30 min, the pellets were collected, resuspended in the same buffer containing 100 mM lactose and 20 mM CHAPS, and incubated for 10 min at 37°C before centrifugation again as described above. The lactose-extracted fractions (lanes 1 and 4), lactose + CHAPS-extracted fractions (lanes 2 and 5), and the insoluble fractions (lanes 3 and 6) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting using antibodies to aminopeptidase N (top) or galectin-4 (bottom). (The 140-kDa band is the transient high-mannose glycosylated form of aminopeptidase N, which is only present in the Mg2-precipitated fraction.) Molecular mass values are indicated.

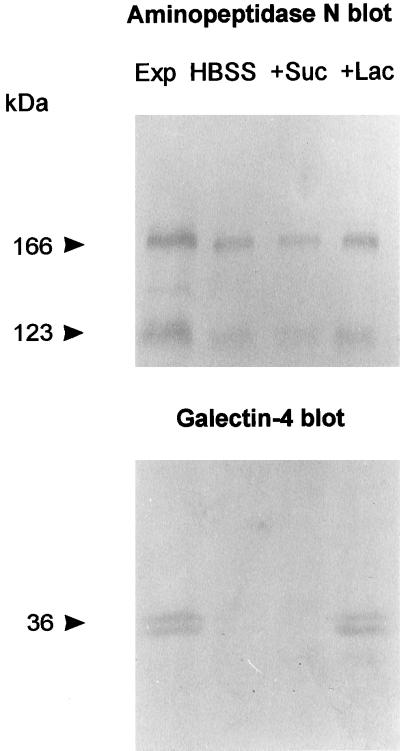

Figure 11 shows that galectin-4 was released from intestinal mucosal explants by a 15-min incubation at 0°C with 100 mM lactose. No release of the lectin was observed by a similar wash in buffer alone or a wash in buffer containing 100 mM sucrose. As a “stalked” integral membrane protein, aminopeptidase N is susceptible to solubilization by proteolytic cleavage by pancreatic proteinases in vivo (Sjöström et al., 1978; Semenza, 1986), and in contrast to galectin-4, some aminopeptidase N was released by all three solutions but, interestingly, in highest amount by the lactose wash. This experiment therefore confirms the extracellular localization of galectin-4 and supports the notion that the lectin is secreted bona fide from the brush border membrane but remains associated at the apical surface by ligand interactions.

Figure 11.

Release of galectin-4 from mucosal explants. Mucosal explants of about 0.1 g (wet weight) were excised and placed in culture dishes and immersed in 1 ml of ice-cold Hanks’ buffered salt solution (HBSS). After 15 min, the HBSS was collected and replaced by 1 ml of ice-cold HBSS containing 100 mM sucrose (+Suc). After 15 min, this solution was replaced by 1 ml of ice-cold HBSS containing 100 mM lactose (+Lac) and incubated 15 min. Protein released by the three wash solutions was precipitated by addition of an equal volume of acetone and pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and equal amounts of sample from each wash were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with a sample of the mucosal explant (Exp). After electrophoresis and transfer to Immobilon, galectin-4 and aminopeptidase N were visualized by Western blotting. Molecular mass values are indicated.

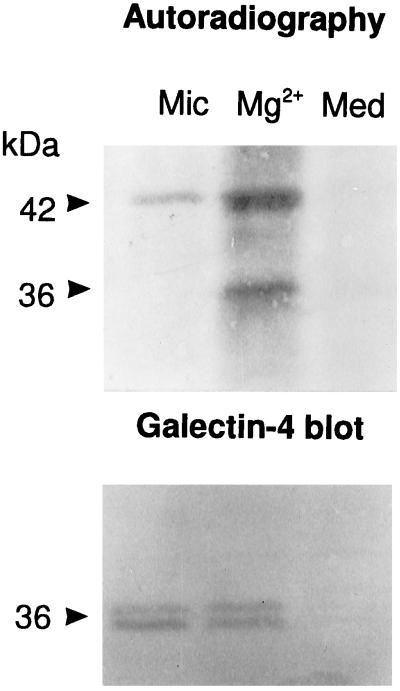

Newly Synthesized Galectin-4 Resides Intracellularly

Figure 12 shows that by 1 h of labeling, newly synthesized galectin-4 was exclusively confined to the Mg2+-precipitated fraction, being absent from the large microvillar pool of the lectin (and the culture medium). In contrast, the 42-kDa band of actin in the microvillar fraction was clearly radioactively labeled by 1 h, showing its rapid association with the microvillar cytoskeleton. Even by 2 h, only minute amounts of radiolabeled galectin-4 were detectable in the microvillar fraction (results not shown). This result demonstrates that newly synthesized galectin-4 does not reach the brush border membrane by rapid free diffusion. Instead, the lectin apparently becomes “trapped” by binding to intracellular structures, resulting in a very slow rate of transport to the apical cell surface.

Figure 12.

Newly synthesized galectin-4 resides intracellularly. Mg2+-precipitated (Mg2+) and microvillar (Mic) fractions were prepared from mucosal explants labeled for 1 h, extracted with CHAPS at 37°C for 10 min, and centrifuged through a sucrose gradient as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. After centrifugation, the five bottom fractions of each gradient were pooled, acetone-precipitated, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with the culture medium (Med). After electrophoresis and electrotransfer onto Immobilon, galectin-4 was visualized by autoradiography (A) and by Western blotting (B). Molecular mass values are indicated. (Notice that only the upper band of the 36-kDa doublet is radiolabeled, indicating that the lower band is generated by proteolysis after biosynthesis).

DISCUSSION

Galectin-4 was originally discovered as a soluble 17-kDa lectin (designated RI-H) present in rat intestinal extracts by Leffler et al. (1989). The same group later cloned and sequenced its cDNA, showing it to encode a 36-kDa protein (Oda et al., 1993). The 17-kDa lectin initially reported constituted the C-terminal domain of the full-length protein harboring one lactose binding site; the N-terminal domain, lost by artefactual degradation under nondenaturing tissue extraction, also possesses a carbohydrate recognition site similar, but not identical, to that of the C-terminal domain. Galectin-4 mRNA is expressed in the small and large intestine and the stomach but not in other organs such as kidney, liver, spleen, skeletal, or heart muscle (Oda et al., 1993). Nothing has as yet been reported about its subcellular localization, ligand(s), or function in the intestine. Chiu et al. (1992, 1994) identified galectin-4 as a major 37-kDa protein present in pig oral epithelial cells, and on the basis of its insolubility and colocalization in immunofluorescence with actin, vinculin, and uvomorulin, they suggested it to be an adherens junction protein in these cells.

In the present work, we initially discovered small intestinal galectin-4 as a prominent component of soluble high molecular weight clusters that were detergent extracted at 37°C from total mucosal membranes. In addition, the lectin was found in preparations of low-temperature detergent-insoluble complexes, containing proteins associated with glycolipid microdomains that resist detergent extraction at this temperature (Brown and Rose, 1992). In both types of preparations, several brush border enzymes, including the two most abundant ones, aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase, are highly enriched as well, suggesting these membrane glycoproteins to be the ligands for galectin-4. Both by subcellular fractionation and immunocytochemistry, a substantial proportion of galectin-4 in the enterocyte was localized to the brush border membrane, implying that it associates with brush border enzymes also in vivo. Finally, a direct interaction between galectin-4 and brush border enzymes was demonstrated by their coimmunopurification and by a colocalization in immunogold electron microscopy. We therefore conclude that galectin-4 be considered an intestinal brush border protein and that its natural ligands include some of the major digestive enzymes confined to the apical cell surface of the enterocyte, in particular aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase.

The brush border enzymes are commonly characterized as “stalked” membrane proteins with short cytoplasmic tails and large heavily glycosylated ectodomains (Semenza, 1986); accordingly, their association with galectin-4 implies the lectin be present at the extracellular surface. Its substantial and rapid release by a lactose wash from microvillar vesicles and from whole mucosal explants confirmed this membrane topology, and as a consequence, we must designate galectin-4 an apically secreted brush border protein. Like some of the other members of the galectin family, notably galectins-1 and -3, galectin-4 is thus subject to externalization by nonclassical secretion. Little is generally known about this pathway, but galectin-3, which is expressed as a major protein in MDCK cells, has been shown to be secreted almost exclusively from the apical cell surface by a nonclassical pathway (Lindstedt et al., 1993). Although secretion was either unaffected or even increased by inhibitors of the classical pathway such as monensin and brefeldin A, it was inhibited by nocodazole and essentially blocked by culture at 20°C, implying that nonclassical secretion may be an event that requires cytoskeletal and vesicular components (Lindstedt et al., 1993). Although not rigorously proven, the membrane translocating step in nonclassical secretion is believed to occur at the plasma membrane (Cooper and Barondes, 1990), and recently two genes, NCE1 and NCE2, of which the latter encodes a multispanning membrane protein required for export of galectin-1 from yeast, were discovered (Cleves et al., 1996).

In a previous work, galectin-1 (L-14) was proposed to be secreted from differentiating myoblasts by a mechanism involving membrane evaginations that pinch off to become labile extracellular vesicles (Cooper and Barondes, 1990). We obtained no morphological evidence to suggest that such a process occurs at the enterocyte brush border membrane, and little if any galectin-4 is probably truly released from the cell. In a previous work on apical secretion of apolipoproteins from cultured mucosal explants, we failed to detect the appearance of a 36-kDa protein in the medium (Danielsen et al., 1993). Nevertheless, this “membrane bleb” model emphasizes a fixed positioning of the lectin in the vicinity of the plasma membrane prior to its secretion. Likewise, the observed insolubility of galectin-4 in the enterocyte most likely reflects its intracellular association with cytoskeletal filaments, and labeling experiments indicated that newly synthesized lectin must bind rapidly to these structures because it only reaches the microvillar membrane very slowly. However, galectin-4 was also seen in association with small vesicles. A speculative model for nonclassical secretion of galectin-4 could be a “piggy-back” model in which the lectin is actively carried to the brush border membrane on the cytosolic face of exocytotic vesicles. These could provide a means of vectorial transport to an otherwise immobilized intracellular galectin-4 and, in so doing, establish an interrelationship between nonclassical secretion and exocytotic membrane traffic. Obviously, much further work is needed to unravel the mechanism underlying nonclassical secretion, but the expression of galectin-4 as a brush border protein in the enterocyte should be a useful model for future studies.

Finally, what is the biological function of galectin-4 in the small intestine? By its exclusive localization at the apical cell surface, it is unlikely to be engaged in either cell–cell or cell–matrix interactions, like galectins expressed in other tissues (Barondes et al., 1994). Instead, its two carbohydrate binding sites enable it to recruit soluble lumenal ligands to the brush border. Likely ligands could be pancreatic digestive enzymes or protease-solubilized brush border enzymes; their recruitment to the cell surface probably enhances the digestive and absorptive capacity of the small intestine. Evidence for such a role is the observation that a lactose wash of mucosal explants released an increased amount of aminopeptidase N (Figure 11). Another role could be to secure the attachment of the brush border “fuzzy coat” or glycocalyx.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ms. Lissi Immerdal, Ms. Kirsten Pedersen, Ms. Mette Ohlsen, Ms. Sussi Forchammer, and Mr. Keld Ottosen are thanked for their excellent technical assistance. Prof. Hans Sjöström and Prof. Ove Norén are both thanked for a valuable discussion of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Novo-Nordic Foundation, the Danish Cancer Society, and the Danish Medical Research Council.

REFERENCES

- Alpers DH. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. L.R. Johnson, New York: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 1469–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Barondes SH, Cooper DNW, Gitt MA, Leffler H. Galectins. Structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20807–20810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerrum OJ, Larsen KP, Wilkien M. In: Modern Methods in Protein Chemistry. Tschesche H, editor. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 1983. pp. 79–124. [Google Scholar]

- Booth AG, Kenny AJ. A rapid method for the preparation of microvilli from rabbit kidney. Biochem J. 1974;142:575–581. doi: 10.1042/bj1420575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth AG, Kenny AJ. A morphometric and biochemical investigation of the vesiculation of kidney microvilli. J Cell Sci. 1976;21:449–463. doi: 10.1242/jcs.21.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Rose JK. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 1992;68:533–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90189-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu ML, Jones JCR, O’Keefe EJ. Restricted tissue distribution of a 37-kDa possible adherens junction protein. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1689–1700. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu ML, Parry DAD, Feldman SR, Klapper DG, O’Keefe EJ. An adherens junction protein is a member of the family of lactose-binding lectins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31770–31776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleves AE, Cooper DNW, Barondes SH, Kelly RB. A new pathway for protein export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1017–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.5.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN, Barondes SH. Evidence for export of a muscle lectin from cytosol to extracellular matrix and for a novel secretory mechanism. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:1681–1691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen EM. Biosynthesis of intestinal microvillar proteins. Pulse-chase labelling studies on aminopeptidase N and sucrase-isomaltase. Biochem J. 1982;204:639–645. doi: 10.1042/bj2040639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen EM. Involvement of detergent-insoluble complexes in the intracellular transport of intestinal brush border enzymes. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1596–1605. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen EM, Hansen GH, Poulsen MD. Apical secretion of apolipoproteins from enterocytes. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1347–1356. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen EM, Sjöström H, Norén O, Bro B, Dabelsteen E. Bio-synthesis of intestinal microvillar proteins. Characterization of intestinal explants in organ culture and evidence for the existence of pro-forms of the microvillar enzymes. Biochem J. 1982;202:647–654. doi: 10.1042/bj2020647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen EM, van Deurs B. A transferrin-like GPI-linked iron-binding protein in detergent-insoluble noncaveolar microdomains at the apical surface of fetal intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:939–950. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.4.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drickamer K, Taylor ME. Biology of animal lectins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:237–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K, Kobayashi T, Kurzchalia TV, Simons K. Glycosphingolipid-enriched, detergent-insoluble complexes in protein sorting in epithelial cells. Biochemistry. 1993;32:6365–6373. doi: 10.1021/bi00076a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen GH, Wetterberg L-L, Sjöström H, Norén O. Immunogold labeling is a quantitative method as demonstrated by studies on aminopeptidase N in microvillar membrane vesicles. Histochem J. 1992;24:132–136. doi: 10.1007/BF01047462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison FL. Soluble vertebrate lectins: ubiquitous but inscrutable proteins. J Cell Sci. 1991;100:9–14. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler H, Masiarz FR, Barondes SH. Soluble lactose-binding vertebrate lectins: a growing family. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9222–9229. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstedt R, Apodaca G, Barondes SH, Mostov KE, Leffler H. Apical secretion of a cytosolic protein by Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11750–11757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muesch A, Hartmann E, Rohde K, Rubartelli A, Sitta R, Rapoport TA. A novel pathway for secretory proteins? Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:86–88. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90186-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Herrmann J, Gitt MA, Turck CW, Burlingame AL, Barondes SH, Leffler H. Soluble lactose-binding lectin from rat intestine with two different carbohydrate-binding domains in the same peptide chain. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5929–5939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G. Anchoring and biosynthesis of stalked brush border membrane proteins: Glycosidases and peptidases of enterocytes and of renal tubuli. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1986;2:255–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.001351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström H, Norén O, Jeppesen L, Staun M, Svensson B. Purification of different amphiphilic forms of a microvillus aminopeptidase from pig small intestine using immunoadsorbent chromatography. Eur J Biochem. 1978;88:503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeke B. In: A manual of quantitative immunoelectrophoresis. Methods and Applications. Axelsen NH, Weeke B, editors. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 1973. pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]