Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) comprise a heterogenous group of malignancies with an often unpredictable course, and with limited treatment options. Thus, new diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic markers are needed. To shed new lights into the biology of NETs, we have by cDNA transcript profiling, sought to identify genes that are either up- or downregulated in NE as compared with non-NE tumour cells. A panel of six NET and four non-NET cell lines were examined, and out of 12 743 genes examined, we studied in detail the 200 most significantly differentially expressed genes in the comparison. In addition to potential new diagnostic markers (NEFM, CLDN4, PEROX2), the results point to genes that may be involved in the tumorigenesis (BEX1, TMEPAI, FOSL1, RAB32), and in the processes of invasion, progression and metastasis (MME, STAT3, DCBLD2) of NETs. Verification by real time qRT–PCR showed a high degree of consistency to the microarray results. Furthermore, the protein expression of some of the genes were examined. The results of our study has opened a window to new areas of research, by uncovering new candidate genes and proteins to be further investigated in the search for new prognostic, predictive, and therapeutic markers in NETs.

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumours, gene expression, microarray, neuroendocrine markers, cell lines

Neuroendocrine (NE) tumours (NETs) belong to a heterogenous group of neoplasms arising from malignant transformation of various types of NE cells (Falkmer, 1993; Wick, 2000; DeLellis, 2001; Hofsli, 2006). Although the majority of NETs are rather slow growing, their biology is often unpredictable, making their management a great challenge (Stephenson, 2006; Vilar et al, 2007). Thus, new insight into the biology of these fascinating tumours could not only make prognostication easier, but also guide in the selection for the right treatment strategy, and contribute in the search for new drug targets. This last issue is of vital importance, as up till now, only surgery has the potential to cure patients with NET disease.

Prediction of the biological behaviour of NETs may be difficult based upon histological criteria alone (Wick, 2000; Stephenson, 2006). Well-differentiated NETs are easily recognised by routine tissue staining and conventional light microscopical (LM) examination, combined with immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of NE markers such as chromogranin A (CHGA) and synaptophysin (SYP). However, dealing with poorly differentiated tumours, it may be difficult to decide whether a tumour exhibits an NE character. Thus, new diagnostic markers are warranted.

In addition to classical NETs, it has been increasingly recognised that both mixed endocrine–exocrine malignant tumours, as well as NE differentiation in common epithelial cancers, may occur (Capella et al, 2000; Sørhaug et al, 2007). The picture is even more complex, as recent research has indicated that use of more sensitive methods such as the tyramide signal amplification technique, will identify more NE tumour cells than today's routine diagnostic procedures manage to do (Sørhaug et al, 2007). With respect to prognosis and treatment, the impact of such NE differentiation in epithelial cancers is mostly unknown.

To shed new lights into the biology of NETs, we have compared the gene expression pattern of a selection of NE tumour cells, with that of a group of non-NE tumour cells. By this approach, we have identified genes that are differentially expressed in NE vs non-NE tumour cells. We propose that some of the genes and their gene products may represent interesting new molecular factors with regard to tumorigenesis, prediction of prognosis and treatment response, as well as may represent novel therapeutic targets.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Six NE and four non-NE cell lines were used in the gene expression analysis. All cell lines, except the BON cell line, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). BON cells (Evers et al, 1991) were a generous gift from Professor Kjell Öberg, Department of Medical Science, Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden, and cultured as described in Hofsli et al (2005). The six NE cell lines represent various NETs: neuroblastomas (SK-N-AS, SK-N-FI), bronchial carcinoids (NCI-H727, UMC-11), gastrointestinal carcinoid (BON), and medullary thyroid carcinoma (TT). The non-NE cell lines were colorectal adenocarcinomas (WiDr, SW480), lung adenocarcinoma (A-427) and glioblastoma (A-172). All these cell lines were cultured according to the requirements given by ATCC.

Isolation of RNA

Cells were cultured in 75 cm2 culture flasks until 80% confluence, harvested and directly subjected to RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy midi kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer's instruction. Two independent biological experiments were performed with each cell line. The quality of the RNA was examined by use of Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The samples were kept frozen at −80°C until further processing.

Microarray hybridisation

Human cDNA arrays with 15 000 probes in duplicate were obtained from Norwegian Microarray Consortium, Oslo, Norway (http://www.microarray.no). These arrays were prepared using sequence-verified human genes (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL, USA). Additional information of cDNA clone preparation and printing is described in detail within the platform GPL3313, of the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL3313). Two negative controls and ten different cDNA spike-in controls from Arabidopsis thaliana (Stratagene SpotReporter, La Jolla, CA, USA) were included in all arrays. Total RNA (2 μg) from the cell lines and from Universal Human Reference RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), was reverse transcribed and labelled with Cy3- and Cy5-attached dendrimer, respectively, using the Genisphere 3DNA Array 350 Expression Array Detection kit (Genisphere, Montvale, NJ, USA), as described in the manufacturer's protocol and previously by us (Yadetie et al, 2003; Nørsett et al, 2004; Hofsli et al, 2005). To reduce the artefacts because of different sensitivity to photobleaching, the biologic replicates of each of the 10 cell lines were randomised by dye-swaps. The arrays were scanned separately by two wavelengths (532 and 633 nm) using ScanArray Express HT scanner (Packard BioScience, Billerica, MA, USA).

Microarray data analysis

The microarray data were prepared according to the MIAME recommendations (Brazma et al, 2001). Image analysis was carried out using the GenePix Pro 4.1 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). All subsequent statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package R (R Development Core Team, 2004), and the LIMMA package from the Bioconduction project (Smyth, 2005). Flawed spots (manually examined) and spots with more than 40% saturated pixels in any channel were removed from the analyses. This resulted in the removal of 17–31% of spots for each array. To compensate for systematic errors each array was normalised using loess normalisation, and then scaled so that the log-transformed ratios had the same median absolute deviation (Yang et al, 2002a, 2002b). Further analyses were based on these normalised log-transformed ratios for each duplicate gene for the 20 microarrays.

To assess the difference between the NE vs non-NE tumour cells for each gene, tests for differential expression were performed using moderated t-tests based on duplicated spots, as implemented in the Limma R package of Smyth et al (2005). This is based on empirical Bayes analysis, where the power of the tests is improved by replacing gene-specific variance estimates with estimates found by borrowing strength from data on the remaining genes. The proportion of truly differentially expressed genes was estimated using the convex decreasing density estimator of Langaas (2005), and the false discovery rate (FDR) was estimated using the method of Storey (2002), with the estimated proportion of truly differentially expressed genes found above inserted.

Cluster analysis was performed as an aid to display the results in a graphical manner. The analysis was performed on the normalised log ratios taking the median over duplicate spots for each gene, and the mean over the dye-swapped replicates. Hierarchical cluster analysis was based on Pearson correlation and the distance between the clusters was both computed using the average- and complete linkage. In addition clustering using the K-means algorithm (using two clusters) was also performed on a selection of the most differentially expressed genes.

Real-time qRT–PCR

cDNA synthesis was performed with 500 ng total RNA in a 10-μl reaction containing 1 × PCR buffer II, 5 mM MgCl2, 500 μM each dNTP, 2.5 μM. Oligo d(T)16 primer, 0.4 U/μl RNase inhibitor and 2.5 U/μl MuLV Reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Mannheim, Germany). cDNA synthesis was performed at 10 min at 25°C followed by 1 h at 48°C and 5 min at 95°C. Design of PCR primers and probes was performed using Primer3 (version 0.2, online software) (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi) and the mRNA sequences obtained using the NCBI RefSeq accession numbers of the respective genes (Table 1). All primers and probes were delivered from Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium, and had an optimal annealing temperature of 56 and 68°C, respectively. TaqMan real-time PCR was performed with 1 × Quantitect Probe PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), 400 nM of each primer, 200 nM TaqMan Probe (Eurogentec) or sybergreen and cDNA equivalent to 62.5 ng total RNA in a total reaction volume of 25 μl. The Real-Time PCR was performed in Stratagene's Mx3000P Real Time PCR system; 15 min at 95°C, 40 thermal cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 30 min at 56°C and 30 s at 76°C. Each sample was measured in triplicate. A negative control without the cDNA template was included, and contamination by genomic DNA was ruled out by performing PCR analysis on template where reverse transcriptase had been omitted in the RT reactions. GAPDH was run in parallel as controls to monitor RNA integrity and to be used for normalisation. Fold induction of gene expression level was estimated by the ΔΔCt-method, where: Fold change=2−ΔΔCt and ΔΔCt=(CtGOI−CtGAPDH)untreated−(CtGOI−CtGAPDH)treated (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). This was accomplished by using the same universal human reference RNA in both the microarray and the real-time RT–PCR analysis;

Table 1. Primers and probes.

| Symbol/gene Bank Accession No. | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Forward reverse probe | Product length |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAALC | actgcccatggcatgtct | S | 66 |

| NM_024812 | tccaggcagatgaggagc | AS | |

| tgggaggtgtctgtgaagcagtca | Probe | ||

| FOSL1 | accctcagtacagccccc | F | 81 |

| NM_005438 | aaggccttcgacgtaccc | AS | |

| aaccccggccaggagtcatc | Probe | ||

| GSTP1 | tgcctatacgggcagctc | F | 102 |

| NM_000852 | cccatagagcccaagggt | AS | |

| aagttccaggacggagacctcacc | Probe | ||

| SCG2 | tggctgaagcaaagaccc | F | 75 |

| NM_003469 | cagccccagagatgagga | AS | |

| tggagcagccctgtctcttatccc | Probe | ||

| M160 | tctatcacgacggcttct | F | 174 |

| NM_174941 | ccattcctgtgcagttca | AS | |

| aatgccacggtctctgctcacttt | Probe | ||

| GAPD | F | ||

| NM_002046 | AS | ||

| Probe |

Genes, primers, and probe sequences of selected genes for confirmation studies. The length, product length, and orientation are given here.

Western blot

Whole cell lysates were prepared from 5–7 × 106 cells which were washed two times in PBS, scraped and harvested directly in 2000 μl SDS-sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 8.7% glycerol; 2% w/v SDS; 5% v/v 2-β mercaptoethanol; 0.09% w/v bromophenol blue). Viscosity was reduced by drawing the suspension through a 21-G needle, cell debris were removed by centrifugation (15 000 g, 10 min), and the supernatant was stored at −80°C. Each extract (15 μl) was boiled and separated on an SDS 10% polyacrylamide gel (running buffer: 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3; 190 mM glycine, 0.1% w/v SDS) before electrotransfer onto Hybond-P membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The transfer was performed in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 190 mM glycine and 20% methanol, pH 8.3, for 1 h at 175 mA. The membranes were treated with 5% nonfat dry milk (Nestlé, Vevey, Switzerland) in TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies diluted (1 : 500–1 : 1000) in TBS with 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 for 2 h, 20°C. The blots were then incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1 : 1000) in TBS with 1% BSA and 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing (4 × 15 min in TBS with 0.05% Tween 20), binding of secondary antibodies was visualised by the ECL-detection system (Amersham) before they were digitally exposed with the KODAK Image Station 2000R (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) for 5 min. GAPDH levels were used to verify protein loading.

The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-human GAPDH (1 : 1000) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-human PRDX2 (1 : 1000) (Abcam), rabbit anti-human HPN (1 : 1000) (Cayman, Michigan, USA), rabbit anti-human SCG2 (1 : 500) (Abcam) and a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural examinations

For IHC investigations, cell pellet was conventionally fixed in 10% neutral formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections, about 4–5 micron thick, were employed for the IHC examinations, using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Lab., Burlingame, CA, USA), and/or Tyramide signal amplification technique (NEN LifeScience Products, Boston, MA, USA), as previously described (Qvigstad et al, 1999). Chromogranin A antiserum (1 : 500) was provided by Incstar (Stillwater, MN, USA), monoclonal mouse antisynaptophysin antiserum (1 : 20) by Dako (Glostrup, Denmark), anti rat neuron-specific enolase (1 : 500) by Polysciences (Warrington, PA, USA), and antineurofilament M (1 : 4000) by Fitzgerald (MA, USA).

For the electron microscopic (EM) investigations, the pellet was fixed in 2% neutral glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide, contrasted with 1% lead citrate and 4% uranyl acetate, and conventionally embedded in Epon. Finally, conventional ultra thin sections were cut and analysed by means of our transmission EMs (JEOL 100CX and Phillips SEI Tecnai 12).

Results

Confirmation of the NE character

To confirm the NE and non-NE character of the cell lines, respectively, IHC and EM investigations were performed in addition to conventional LM examination. The employed NE cell lines (NCI-H727, UMC-11, SK-N-AS, SK-N-FI, TT, BON) encompass NE features with the expression of CHGA and SYP as the confined NE marker. The four cell lines known to be of non-NE character (WiDr, A-172, A-427, SW480), showed no staining with CHGA and SYP (data not shown). In addition, the cells were examined for the expression of ENO2 (enolase 2/neuron-specific enolase), an NE marker thought to be less specific than the conventional NE markers CHGA and SYP. All the presumed NE cell lines showed positive immunoreactivity to enolase 2, and this was also the case for the non-NE cell lines A-427 and SW480 (data not shown). EM investigations demonstrated occurrence of typical NE secretion granules in all the NE tumour cells, but not in any of the non-NE tumour cells, thus confirming the predefined NE/non-NE characteristics of the cell lines used.

Genes differentially expressed in NE vs non-NE tumour cells

Having confirmed the NE and non-NE character of the cell lines, respectively, we performed transcript profiling by cDNA microarray analysis in an effort to identify new NE-specific genes, and by this, get more insight into the biology of NETs.

By using the convex decreasing density estimator for the proportion of true null hypotheses as presented in Langaas (2005), we expect 5.5% of the genes studied to be differentially expressed in NE vs non-NE cells. The 200 most significant genes (P-value 0.008/FDR 0.49) in the comparison of the NE vs non-NE tumour cell groups are sequence verified, and 153 genes are given as Supplementary Information in the gene expression omnibus (GEO) GSE4328.

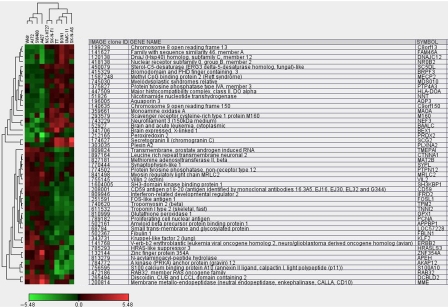

Based on information from the GO annotation database and literature search, these genes are displayed with the log ratio and biological processes in which they are likely to be involved. The up- and downregulated genes range from log2 5.87 to −2.92, respectively. The 70 most highly up- and downregulated genes, are shown in Table 2. A hierarchical cluster analysis of the 48 most significantly differentially expressed genes (P-value 0.0014/FDR 0.2823) are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2. Differentially expressed genes in NE vs non-NE tumour cells.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | UGCluster | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | |||

| SCG3 | Secretogranin III | Hs.232618 | 26.56 |

| SCG2 | Secretogranin II (chromogranin C) | Hs.516726 | 15.29 |

| DDC | Dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) | Hs.359698 | 9.65 |

| BAALC | Brain and acute leukaemia, cytoplasmic | Hs.533446 | 7.78 |

| NEF3 | Neurofilament 3 | Hs.458657 | 7.66 |

| C8orf13 | Chromosome 8 open reading frame 13 | Hs.124299 | 7.27 |

| BEX1 | Brain expressed, X-linked 1 | Hs.334370 | 6.76 |

| RAPGEF5 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 5 | Hs.174768 | 6.01 |

| PLXNA2 | Plexin A2 | Hs.497626 | 5.88 |

| Hypothetical LOC90024 | Hs.534513 | 5.30 | |

| MGC17299 | Hypothetical protein MGC17299 | Hs.104476 | 5.11 |

| PRDX2 | Peroxiredoxin 2 | Hs.432121 | 5.04 |

| M160 | Scavenger receptor cysteine-rich type 1 protein M160 | Hs.49636 | 5.01 |

| DNAJC12 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homologue, subfamily C, member 12 | Hs.260720 | 4.50 |

| MAOA | Monoamine oxidase A | Hs.183109 | 4.48 |

| FAM46A | Family with sequence similarity 46, member A | Hs.10784 | 4.29 |

| FNDC5 | Fibronectin type III domain containing 5 | Hs.524234 | 4.11 |

| CLDN4 | Claudin 4 | Hs.520942 | 3.96 |

| CACNA1H | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, α 1H subunit | Hs.459642 | 3.95 |

| ITGA10 | Integrin, α 10 | Hs.158237 | 3.88 |

| HLA-DOA | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DO α | Hs.351874 | 3.70 |

| CNTN1 | Contactin 1 | Hs.143434 | 3.65 |

| NR0B2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 0, group B, member 2 | Hs.427055 | 3.57 |

| TAGLN3 | Transgelin 3 | Hs.169330 | 3.45 |

| PEG10 | Paternally expressed 10 | Hs.147492 | 3.37 |

| EGLN3 | Egl nine homologue 3 (C. elegans) | Hs.135507 | 3.36 |

| MBP | Myelin basic protein | Hs.551713 | 3.36 |

| ABCC6 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 6 | Hs.13188 | 3.26 |

| SFMBT2 | Scm-like with four mbt domains 2 | Hs.407983 | 3.21 |

| C9orf150 | Chromosome 9 open reading frame 150 | Hs.445356 | 3.17 |

| CDNA FLJ37828 fis, clone BRSSN2006575 | Hs.123119 | 3.15 | |

| HIPK2 | Homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 | Hs.397465 | 3.10 |

| CDNA FLJ45289 fis, clone BRHIP3002363 | Hs.556782 | 3.08 | |

| C17orf28 | Chromosome 17 open reading frame 28 | Hs.11067 | 3.05 |

| C3orf14 | Chromosome 3 open reading frame 14 | Hs.47166 | 2.94 |

| LIMD1 | LIM domains containing 1 | Hs.193370 | 2.92 |

| HPN | Hepsin (transmembrane protease, serine 1) | Hs.182385 | 2.82 |

| MDS010 | x 010 protein | Hs.231750 | 2.77 |

| MS4A1 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member1 | Hs.438040 | 2.75 |

| NAPB | N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein, β | Hs.269471 | 2.69 |

| PBX1 | Pre-B-cell leukaemia transcription factor 1 | Hs.493096 | 2.63 |

| APG4A | APG4 autophagy 4 homologue A | Hs.8763 | 2.60 |

| ARHGAP26 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 26 | Hs.293593 | 2.56 |

| GAB2 | GRB2-associated binding protein 2 | Hs.429434 | 2.53 |

| AQP3 | Aquaporin 3 | Hs.234642 | 2.45 |

| MGC4645 | Hypothetical protein MGC4645 | Hs.395306 | 2.44 |

| PTP4A3 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 3 | Hs.43666 | 2.40 |

| TP53I11 | Tumour protein p53-inducible protein 11 | Hs.554791 | 2.36 |

| Clone IMAGE:121214 mRNA sequence | Hs.283883 | 2.36 | |

| C14orf132 | Chromosome 14 open reading frame 132 | Hs.6434 | 2.33 |

| SC5DL | Sterol-C5-desaturase | Hs.287749 | 2.29 |

| CENTB5 | Centaurin, β 5 | Hs.535257 | 2.15 |

| ARHGAP5 | Rho GTPase-activating protein5 | Hs.525287 | 2.13 |

| KIAA0924 | KIAA0924 protein | Hs.560561 | 2.10 |

| C6orf1 | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 1 | Hs.381300 | 2.10 |

| SGTB | Small glutamine-rich tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) | Hs.287971 | 2.05 |

| NNT | Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase | Hs.482043 | 2.05 |

| BRPF3 | Bromodomain and PHD finger containing, 3 | Hs.520096 | 1.99 |

| TBC1D16 | TBC1 domain family, member 16 | Hs.369819 | 1.98 |

| IRF2BP2 | Interferon regulatory factor 2-binding protein 2 | Hs.350268 | 1.94 |

| DKFZp434H2226 | LMBR1 domain containing 2 (DKFZp434H2226) | Hs.294103 | 1.93 |

| CALM1 | Calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) | Hs.282410 | 1.82 |

| C6orf209 | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 209 | Hs.271643 | 1.79 |

| ZCCHC3 | Zinc finger, CCHC domain containing 3 | Hs.28608 | 1.78 |

| IRS2 | Insulin receptor substrate 2 | Hs.442344 | 1.76 |

| RGS18 | Regulator of G-protein signalling 18 | Hs.440890 | 1.70 |

| SCFD1 | Sec1 family domain containing1 | Hs.369168 | 1.69 |

| TCEAL8 | Transcription elongation factor A (SII)-like 8 | Hs.389734 | 1.67 |

| SEC23B | Sec23 homologue B (S. cerevisiae) | Hs.369373 | 1.59 |

| MECP2 | Methyl CpG-binding protein 2 | Hs.200716 | 1.59 |

| Downregulated | |||

| MME | Membrane metallo-endopeptidase | Hs.307734 | 0.12 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (acute-phase response factor) | Hs.463059 | 0.13 |

| MEOX1 | Homeobox protein MOX-1 | Hs.438 | 0.14 |

| TMEPAI | Transmembrane, prostate androgen induced RNA | Hs.517155 | 0.15 |

| RAB32 | RAB32, member RAS oncogene family | Hs.287714 | 0.17 |

| KLF2 | Kruppel-like factor 2 (lung) | Hs.107740 | 0.17 |

| ZNF354A | Zinc finger protein 354A | Hs.484324 | 0.17 |

| LOC255104 | Hypothetical protein LOC255104 | Hs.466729 | 0.18 |

| S100A10 | S100 calcium-binding protein A10 (annexin II ligand, calpactin I, light polypeptide (p11)) | Hs.143873 | 0.18 |

| DCBLD2 | Discoidin, CUB and LCCL domain containing 2 | Hs.203691 | 0.18 |

| HSPC016 | Hypothetical protein HSPC016 | Hs.356440 | 0.20 |

| USP4 | Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 4 (proto-oncogene) | Hs.77500 | 0.21 |

| GSTP1 | Glutathione S-transferase pi | Hs.523836 | 0.22 |

| AKAP12 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein (gravin) 12 | Hs.371240 | 0.23 |

| MGC7036 | Hypothetical protein MGC7036 | Hs.488173 | 0.24 |

| ZF | HCF-binding transcription factor Zhangfei | Hs.535319 | 0.25 |

| AMOTL2 | Angiomotin like 2 | Hs.426312 | 0.25 |

| LMO2 | LIM domain only 2 | Hs.34560 | 0.25 |

| CETN2 | Centrin, EF-hand protein, 2 | Hs.82794 | 0.27 |

| RUNX1 | Runt-related transcription factor 1 (acute myeloid leukaemia 1; aml1 oncogene) | Hs.149261 | 0.27 |

| HRASLS3 | HRAS-like suppressor 3 | Hs.502775 | 0.28 |

| APEH | N-acylaminoacyl-peptide hydrolase | Hs.517969 | 0.28 |

| ERBB2 | V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukaemia viral oncogene homologue 2, neuro/glioblastoma derived oncogene homologue | Hs.446352 | 0.28 |

| YAP1 | Yes-associated protein 1, 65kDa | Hs.503692 | 0.31 |

| CD9 | CD9 antigen (p24) | Hs.114286 | 0.31 |

| TNNI2 | Troponin I, skeletal, fast | Hs.523403 | 0.32 |

| FBLN1 | Fibulin 1 | Hs.24601 | 0.32 |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium binding protein A8 (calgranulin A) | Hs.416073 | 0.33 |

| LOC91614 | Novel 58.3 KDA protein | Hs.280990 | 0.34 |

| CTSL | Cathepsin L | Hs.418123 | 0.34 |

| PRPS2 | Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 2 | Hs.104123 | 0.35 |

| TMSB10 | Thymosin, β 10 | Hs.446574 | 0.37 |

| TPM2 | tropomyosin 2 (β) | Hs.300772 | 0.37 |

| SH3KBP1 | SH3-domain kinase-binding protein 1 | Hs.444770 | 0.38 |

| FOSL1 | FOS-like antigen 1 | Hs.283565 | 0.39 |

| ODC1 | Ornithine decarboxylase 1 | Hs.467701 | 0.39 |

| MRLC2 | Myosin regulatory light chain MRLC2 | Hs.464472 | 0.39 |

| LOC57228 | Hypothetical protein from clone 643 | Hs.558523 | 0.39 |

| CD164 | CD164 antigen, sialomucin | Hs.520313 | 0.41 |

| CAMK1 | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I | Hs.434875 | 0.41 |

| RPA3 | Replication protein A3, 14kDa | Hs.487540 | 0.41 |

| VIL2 | Villin 2 (ezrin) | Hs.487027 | 0.42 |

| IFRD2 | Interferon-related developmental regulator 2 | Hs.315177 | 0.42 |

| NLGN2 | Neuroligin 2 | Hs.26229 | 0.43 |

| CD59 | CD59 antigen p18-20 | Hs.278573 | 0.43 |

| ZBTB4 | Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 4 | Hs.35096 | 0.45 |

| TXNRD1 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | Hs.337766 | 0.46 |

| MAT2B | Methionine adenosyltransferase II, β | Hs.54642 | 0.46 |

| BMP1 | Bone morphogenetic protein 1 | Hs.1274 | 0.46 |

| HRB2 | HIV-1 rev binding protein 2 | Hs.205558 | 0.47 |

| APPBP1 | Amyloid β precursor protein binding protein 1, 59kDa | Hs.460978 | 0.48 |

| CTNNA1 | Catenin (cadherin-associated protein), α 1, 102kDa | Hs.445981 | 0.49 |

| COMMD6 | COMM domain containing 6 | Hs.508266 | 0.51 |

| MAP4 | Microtubule-associated protein4 | Hs.517949 | 0.51 |

| PSMD12 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 12 | Hs.4295 | 0.51 |

| PLP2 | Proteolipid protein 2 (colonic epithelium-enriched) | Hs.77422 | 0.52 |

| GPX1 | Glutathione peroxidase 1 | Hs.76686 | 0.52 |

| SYPL | Synaptophysin-like protein | Hs.80919 | 0.54 |

| PICALM | Phosphatidylinositol-binding clathrin assembly protein | Hs.163893 | 0.56 |

| PTPN12 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 12 | Hs.61812 | 0.56 |

| PSMA5 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit,α type5 | Hs.485246 | 0.58 |

| ST13 | Suppression of tumorigenicity 13 (colon carcinoma) (Hsp70 interacting protein) | Hs.546303 | 0.58 |

| SR140 | U2-associated SR140 protein | Hs.529577 | 0.58 |

| PAWR | PRKC, apoptosis, WT1, regulator | Hs.406074 | 0.59 |

| EGR3 | Early growth response 3 | Hs.534313 | 0.60 |

| HNRPH1 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1 (H) | Hs.202166 | 0.60 |

| GLTSCR2 | Glioma tumour suppressor candidate region gene 2 | Hs.421907 | 0.61 |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | Hs.147433 | 0.61 |

| PSMB3 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, β type, 3 | Hs.82793 | 0.61 |

| EMR3 | Egf-like module containing, mucin-like, hormone receptor-like 3 | Hs.295626 | 0.62 |

Genes significantly (P<0.007) up- or downregulated in the neuroendocrine cell lines compared with the non-neuroendocrine cell lines. The first half of the table shows downregulated genes whereas the last part of the table shows the upregulated genes. The genes are all given with unigene cluster id's, official gene name and symbols in addition to their respective ratio (NE vs non-NE).

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering analysis. A hierarchical clustering algorithm was used to cluster experimental samples on the basis of similarities of gene expression. Relationships between the experimental samples are summarised as dendrograms, in which the pattern and length of the branches reflect the relatedness of the samples (NE vs non-NE). Data are presented in a matrix format: each row represents a cDNA clone (identified with UniGene gene symbol, name and IMAGE clone id) and each column an individual mRNA (average gene expression log ratio) sample of NE (BON, TT, SK-N-AS, SK-NFI, NCI-H727, UMC-11) and non-NE (WiDr, A-172, SW480, A-427) cells. The results presented represent the ratio of hybridisation of fluorescent cDNA probes prepared from each experimental mRNA sample to a reference mRNA sample. These ratios (log) are a measure of relative gene expression in each experimental sample and were depicted according to the colour scale shown at the bottom.

The three most highly overexpressed genes: SCG3 (26.6 fold), SCG2 (15.3 fold) and DDC (9.6 fold) (Table 2), have previously been shown to be linked to NE tumour biology, thus confirming the reliability of our study design. SCG3 and SCG2 are both members of the chromogranin–secretogranin family of NE secretory, acidic glycoproteins (Taupenot et al, 2003), and DDC has more recently been shown to be expressed in various NETs (Uccella et al, 2006). Furthermore, the high expression of MAOA in our study, support previous findings of high expression of monoaminoxidase A in various NETs (Örlefors et al, 2003).

NETs in general are relatively slow growing tumours with a less invasive character than many epithelial cancers. Several genes thought to play a role in the processes of invasion, tumour progression and metastasis (MME, STAT3, DCBLD2, S100A10, CD9, S100A8) were highly downregulated in the NE vs the non-NE tumour group (Table 2 and Supplementary Information). The three most highly downregulated genes in our study were MME (0.12 fold), STAT3 (0.13) and DCBLD2 (0.14 fold). Our results also point to differences in expression of several genes thought to be involved in the process of tumorigenesis (BEX1, TMEPAI, FOSL1, RAB32, ERBB2) (Table 2 and Supplementary Information). Well-differentiated NETs are in general relatively insensitive to various chemotheurapeutic drugs, and thus it is interesting to note variations between the two groups in the expression of genes known to be involved in the process of drug resistance (STAT3, PRXD2 ABCC6, GSTP1) (Table 2 and Supplementary Information). Nearly 50% of the upregulated, and 16% of the downregulated genes are in the GO database defined as having an unknown function (Supplementary Information).

Validation by real-time qRT–PCR

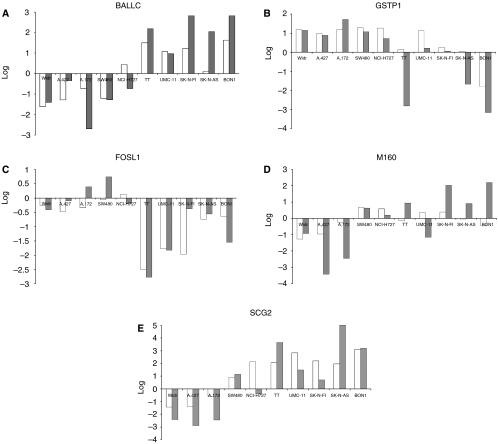

To validate the microarray results, we performed real-time quantitative RT–PCR analysis of five selected genes using the same RNA samples as those used in the microarray analysis. The selection of the genes (BAALC, SCG2, GSTP1, FOSL1, M160) were based upon a combination of P-value, differential expression, and biological function. In general, 70% of the genes found to be differentially expressed in the microarray study were confirmed by RT–PCR (Figure 2). This seems to be in accordance with previous studies using cDNA arrays (Kothapalli et al, 2002; Hofsli et al, 2005), and underlines the need to verify microarray data by additional methods.

Figure 2.

RT–PCR confirmation of microarray results. A selection of genes (A–E) was also analysed by semi quantitative real-time RT–PCR (grey), and compared to the respective ratios of the microarray analysis (white). The two methods correlated at 9/10 cell lines at best, and the lowest correlated at 6/10 cell lines. Y axis shows the log-transformed ratio of both the microarray and the RT–PCR, based on the fold change ratios and the delta–delta Ct calculation, respectively.

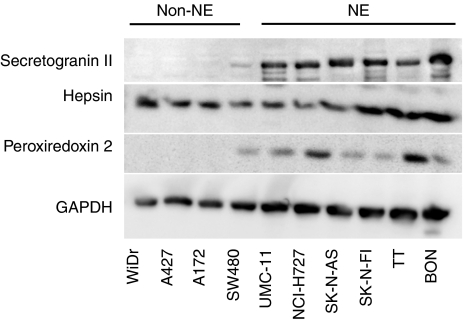

Protein expression analysis

To investigate whether the difference in gene expression level was followed by a similar expression pattern at the protein level, we first performed western blot analysis of cell lysates. The selection of gene products analysed (secretogranin II, peroxiredoxin 2, hepsin) was based upon a combination of the expression level found in the microarray analysis, biological relevance, and availability of antibodies. As seen in Figure 3, the protein expression of the NE marker secretogranin II, correlated well with the gene expression level of SCG2 found in the microarray analysis (15-fold upregulated)(Table 2), and in the real-time RT–PCR analysis (Figure 2). All the NE tumour cell lines express a high level of SCG2, whereas the expression level in the non-NE cell group is almost undetectable. Hepsin (2.8 fold upregulated in the microarray analysis) was found to be expressed in all cell lines and without any significant difference in NE vs non-NE cells (Figure 3). Thus, hepsin is ruled out as a possible new diagnostic marker of NET disease. On the contrary, the level of peroxiredoxin 2 expression (5 fold upregulated in the microarray analysis) was significantly different in the two groups (Figure 3). Peroxiredoxin 2 was clearly detectable in the NE cell line group, but almost undetectable in the non-NE cell group, thus pointing out peroxiredoxin 2 as an interesting new NE biomarker. The difference in secretogranin II and peroxiredoxin 2 expression was also confirmed by IHC analysis (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Western blot. Western blot analysis was performed on cell lines (NE and non-NE) with the antibodies against secretogranin II, hepsin, peroxiredoxin 2 and GAPDH. Cells were harvested and prepared as described in Materials and methods.

In addition to secretogranin II and peroxiredoxin 2, our study points to NEFM as another interesting candidate marker of NET disease. NEFM, which was upregulated by a factor of 7.7 in the microarray analysis (Table 2), was by IHC shown to be expressed only in the NE tumour cells group (data not shown).

Discussion

Although last year's genomic and proteomic research have uncovered some genes and gene products thought to have an important function in the context of NE tumour biology (Hofsli, 2006), still much is unknown concerning which factors that are important with regard to the causes and behaviours of NET diseases. The results of this study contribute to an increased insight into the biology of these tumours, by identifying genes that are differentially expressed in NE tumour cells as compared with non-NE tumour cells. We believe that some of these genes and gene products represent interesting candidates in the search for new prognostic, predictive and therapeutic markers. The study also point to genes that may play a role in the tumorigenesis of NETs.

The three most highly overexpressed genes in the NE vs the non-NE tumour cell group (SCG3, SCG2 and DDC) (Table 2), have all previously been described in the context of NE tumour biology, thus confirming the reliability of our study design. Although secretogranin II and one of its split product (Taupenot et al, 2003; Guillemot et al, 2006) have been shown to be expressed in various types of NETs, investigations of the expression of secretogranin III in NETs have so far not been reported. The enzyme dopa decarboxylase (DDC)(catecholamine biosynthesis) has more recently been shown to be expressed in various NETs, such as bronchial carcinoids and poorly differentiated NE carcinomas of the lung (Uccella et al, 2006). It has also been shown to be a marker of neuroblastoma in children (Bozzi et al, 2004), and of NE differentiation in prostate carcinoma (Wafa et al, 2007). Another gene known to be involved in catecholamine metabolism, MAOA (Toninello et al, 2006), was also identified as highly expressed in the NET group (Table 2), a finding that was confirmed by IHC analysis (not shown). This supports previous findings demonstrating a high expression of MAOA in gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) tumours (Örlefors et al, 2003). To conclude, we believe that SCG3, SCG2 and DDC could represent useful additional biomarkers in NET diseases, and that they perhaps should be implemented in the standard diagnostic panel of NE biomarkers. Furthermore, measurement of MAOA activity may, as recently shown in a baboon model, aid in understanding the pathophysiology of NETs (Murthy et al, 2007).

In addition to these above-mentioned potentially important NET biomarkers, our study points to NEFM, PRDX2, and CLDN4 as other interesting candidate markers of NET disease. The finding of an upregulation of the NEFM gene (a marker of neuronal differentiation) is in accordance to findings by Perez et al (1990), who found NEFM expression in a subset of pancreatic islet cell and rectal carcinoid tumours, although rarely in ileojejunal carcinoid tumours. Thus, the message brought from our study and that of Perez is, that neurofilament subtyping could well become a potential diagnostic tool with regard to NETs.

Also the antioxidant enzyme peroxiredoxin 2 (PRXD2) (antiapoptosis) was highly upregulated in the NE tumour cell group. PRXD2 was previously shown to be elevated in several human cancers, to confer resistance to chemo- and radiation therapy, and to promote tumour progression and metastasis (Lee et al, 2007). The tight junction protein claudin 4 (CLDN4) is also frequently overexpressed in several cancers, and is thought to represent a promising target for cancer detection, diagnosis, and therapy (Morin, 2005; Kominsky et al, 2007). A loss of claudin 4 expression at the invasive front in colorectal cancer correlates with cancer invasion and metastasis (Ueda et al, 2007), and thus the finding in our study of a rather high level of CLDN4 in the NE tumour group, may reflect NETs in general lower malignant phenotype. However, our results are in contrast to that of Moldvay et al (2007), who more recently have demonstrated that a majority of bronchial carcinoids express a lower level of CLDN4 than other histological types of primary bronchial cancers.

Several of the differentially expressed genes turned out to have unknown functions (Supplementary Information; GEO GSE4328). We focused on BAALC (brain and acute leukaemia, cytoplasmic), as a high mRNA transcript level of this gene has been found in tissues of neuroectodermal origin (Tanner et al, 2001), and has been shown to be an independent adverse prognostic factor in various acute leukaemias (Marcucci et al, 2005; Baldus et al, 2007). The high expression of BAALC found in the microarray analysis (Table 2), was confirmed by real-time PCR analysis (Figure 2).

Our results also point to differences in expression of several genes thought to be involved in the process of tumorigenesis (BEX1, TMEPAI, FOSL1, RAB32, ERBB2) (Table 2; Supplementary Information). One interesting find is the high expression of the novel BEX1 gene (brain expressed, X-linked 1) in the NE tumour cell group (Table 2). Previous studies have revealed a high expression of this gene in brain, but also in peripheral organs such as liver, pancreas, testis, and ovary (Yang et al, 2002a, 2002b; Alvarez et al, 2005). It has more recently been suggested that BEX1 may play a role as a tumour suppressor in malignant glioma (Foltz et al, 2006). A very low expression was observed for the TMEPAI gene (Table 2), which is involved in androgen receptor signaling, and is proposed to play a role in prostate tumorigenesis (Xu et al, 2003). TMEPAI has been shown to be overexpressed in various solid tumours, probably because of abnormal activation of the EGF pathway (Giannini et al, 2003). Also the oncogenic transcription factor FOSL1, was downregulated in the NE tumour cell group. FOSL1 is upregulated in several solid cancers, and is becoming a new target for cancer intervention (Young and Colburn 2006). The ras family member RAB32, has been proposed to represent a component of the oncogenic pathway of microsatellite instability-high gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (Shibata et al, 2006). In our study, RAB32 was highly downregulated in the NE vs the non-NE group. Also the ERBB2 gene expression level was significantly lower in the NE tumour cell group than in the non-NET group. The expression level of this member of the oncogenic EGF receptor family, has previously been reported as a variable in various NETs (cf. Hofsli, 2006). So far, there is no strong evidence that ERBB2 amplification/overexpression could play an important role in NET pathogenesis, or that it could be a potential target for treatment, as is the case in various epithelial cancers (Hsieh and Moasser 2007). To conclude, our study is the first to reveal the expression pattern of BEX1, TMEPAI, FOSL1, and RAB32 in NE tumour cells, and we believe that they represent interesting novel candidates in the context of NET tumorigenesis.

A hallmark of NETs in general, are that they are relatively slow growing and less invasive in character. Thus, its interesting to note that several genes thought to play a role in the processes of invasion, tumour progression and metastasis (MME, STAT3, DCBLD2, S100A10, CD9, S100A8) were highly downregulated in the NE vs the non-NE tumour group (Table 2). The most highly downregulated gene was MME. A loss or decrease in MME has been reported in a variety of malignancies, and reduced expression results in the accumulation of higher peptide concentrations that could mediate neoplastic progression (Sumitomo et al, 2005). Loss of this endopeptidase also leads to AKT1 (protein kinase B) activation, and contributes to the clinical progression of prostate cancer (Osman et al, 2006). STAT3 (the signal-transducer and activator –of transcription 3) is thought to play an important role in both tumorigenesis and tumour progression, and is often constitutively activated in tumour cells (Aggarwal et al, 2006). Thus, inhibitors of STAT3 activation have potential for both prevention and therapy of cancer (Huang, 2007). In lung cancer, DCBLD2 has been shown to be highly upregulated in the cell line NCI-H460-LNM35, in association with its acquisition of metastatic phenotype, and also upregulated in high frequency in metastatic lesions from lung cancers (Koshikawa et al, 2002). It is also shown that DCBLD2 may play a role in cell motility (Nagai et al, 2007), and thus it is suggested that this novel gene may become a target of therapy to inhibit metastasis of lung cancers.

The plasminogen receptor S100A10 is found overexpressed in many cancer cells, and seems to play an important role in cancer cell invasiveness and metastasis (Kwon et al, 2005). RNA interference-mediated downregulation of S100A10 gene expression in colorectal cancer cells, has been shown to result in a complete loss in plasminogen-dependent cellular invasiveness (Zhang et al, 2004). More recently it has been shown by IHC analysis that S100A10 expression in thyroid neoplasms contributes to the aggressive characteristic of anaplastic carcinoma (Ito et al, 2007). To conclude, the very low levels of various genes known to be involved in the processes of invasion, tumour progression and metastasis could perhaps reflect the in general more slow growing and less invasive character of NETs.

In addition to the already mentioned STAT3 and PRXD2, other genes that have been linked to the phenomenon of drug resistance, were identified as differentially expressed (ABCC6, GSTP1). Well-differentiated NETs are in general relatively insensitive to various chemotheurapeutic drugs. Thus, it is interesting to note that our study reveals a relatively high expression of ABCC6 (ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (CFTR/MRP), member 6), one member of the MRP subfamily involved in multi-drug resistance (Beck et al, 2005). Endocrine G-cells in the stomach has been shown to express high level of ABCC6 (Beck et al, 2005). However, our study is the first to report ABCC6 expression in NE tumour cells. The antiapoptosis gene GSTP1, was highly downregulated in the NET group (Table 2). In prostate cancer, the loss of expression of GSTP1 is the most common genetic alteration reported (Meiers et al, 2007). A comprehensive survey of GSTP1 expression in NETs has so far not been performed, but one study has been undertaken, showing that the expression of this drug-resistant protein is significantly lower in large cell NE carcinoma of the lung than in the other more common histological types of lung cancer (Okada et al, 2003).

In conclusion, the results of our study add new important lights into the understanding of NE tumour biology, by identifying genes differentially expressed in NE as compared with non-NE tumour cells. In addition to potential new diagnostic markers (SCG2, SCG3, DDC, MAOA, NEFM, CLDN4, PEROX2), genes critical in the processes of tumour invasion, progression and metastasis (MME, STAT3, DCBLD2, S100A10, CD9, S100A8), tumorigenesis (BEX1, TMEPAI, FOSL1, RAB32) and drug-resistance (ABCC6, GSTP1) were identified, as well as several genes with hitherto unknown functions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, The Norwegian Cancer Society, The Norwegian Research Council and the Cancer Fund at the St Olavs Hospital HF, Trondheim. We gratefully acknowledge the advice given by professor Ursula Falkmer, Oncology Unit, St Olavs Hospital HF, Trondheim, Norway, and professor Sture Falkmer, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim for advise and help with the characterisation of the cell lines used. Furthermore, we thank Kåre E Tvedt, PhD, Associate Professor of Morphology, and Head of the Electron Microscopy Unit of St Olavs University Hospital, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, for his excellent assistance in the ultra structural investigations. We also thank Ole Jonny Steffensen, Department of pathology, Ålesund Hospital, Ålesund, Norway, for help with the IHC analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary Material

References

- Aggarwal BB, Sethi G, Ahn KS, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Kunnumakkara AB, Sung B, Ichikawa H (2006) Targeting signal-transducer-and-activator-of-transcription-3 for prevention and therapy of cancer: modern target but ancient solution. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1091: 151–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez E, Zhou W, Witta SE, Freed CR (2005) Characterization of the Bex gene family in humans, mice, and rats. Gene 357: 18–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus CD, Martus P, Burmeister T, Schwartz S, Gokbuget N, Bloomfield CD, Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Hofmann WK (2007) Low ERG and BAALC expression identifies a new subgroup of adult acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia with a highly favorable outcome. J Clin Oncol 25: 3739–3745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck K, Hayashi K, Dang K, Hayashi M, Boyd CD (2005) Analysis of ABCC6 (MRP6) in normal human tissues. Histochem Cell Biol 123: 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzi F, Luksch R, Collini P, Gambirasio F, Barzano E, Polastri D, Podda M, Brando B, Fossati-Bellani F (2004) Molecular detection of dopamine decarboxylase expression by means of reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction in bone marrow and peripheral blood: utility as a tumor marker for neuroblastoma. Diagn Mol Pathol 13: 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, Sherlock G, Spellman P, Stoeckert C, Aach J, Ansorge W, Ball CA, Causton HC, Gaasterland T, Glenisson P, Holstege FC, Kim IF, Markowitz V, Matese JC, Parkinson H, Robinson A, Sarkans U, Schulze-Kremer S, Stewart J, Taylor R, Vilo J, Vingron M (2001) Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat Genet 29: 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella C, La Rosa S, Uccella S, Billo P, Cornaggia M (2000) Mixed endocrine-exocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Semin Diagn Pathol 17: 91–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLellis RA (2001) The neuroendocrine system and its tumors: an overview. Am J Clin Pathol 115(Suppl): S5–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers BM, Townsend Jr CM, Upp JR, Allen E, Hurlbut SC, Kim SW, Rajaraman S, Singh P, Reubi JC, Thompson JC (1991) Establishment and characterization of a human carcinoid in nude mice and effect of various agents on tumor growth. Gastroenterology 101: 303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkmer S (1993) Phylogeny and ontogeny of the neuroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 22: 731–752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz G, Ryu GY, Yoon JG, Nelson T, Fahey J, Frakes A, Lee H, Field L, Zander K, Sibenaller Z, Ryken TC, Vibhakar R, Hood L, Madan A (2006) Genome-wide analysis of epigenetic silencing identifies BEX1 and BEX2 as candidate tumor suppressor genes in malignant glioma. Cancer Res 66: 6665–6674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini G, Ambrosini MI, Di Marcotullio L, Cerignoli F, Zani M, MacKay AR, Screpanti I, Frati L, Gulino A (2003) EGF- and cell-cycle-regulated STAG1/PMEPA1/ERG1.2 belongs to a conserved gene family and is overexpressed and amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Mol Carcinog 38: 188–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot J, Barbier L, Thouennon E, Vallet-Erdtmann V, Montero-Hadjadje M, Lefebvre H, Klein M, Muresan M, Plouin PF, Seidah N, Vaudry H, Anouar Y, Yon L (2006) Expression and processing of the neuroendocrine protein secretogranin II in benign and malignant pheochromocytomas. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1073: 527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofsli E (2006) Genes involved in neuroendocrine tumour biology. Pituitary 9: 165–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofsli E, Thommesen L, Yadetie F, Langaas M, Kusnierczyk W, Falkmer U, Sandvik AK, Laegreid A (2005) Identification of novel growth factor-responsive genes in neuroendocrine gastrointestinal tumour cells. Br J Cancer 92: 1506–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh AC, Moasser MM (2007) Targeting HER proteins in cancer therapy and the role of the non-target HER3. Br J Cancer 97: 453–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S (2007) Regulation of metastases by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathway: clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res 13: 1362–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Arai K, Nozawa R, Yoshida H, Higashiyama T, Takamura Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, Kuma K, Miyauchi A (2007) S100A10 expression in thyroid neoplasms originating from the follicular epithelium: contribution to the aggressive characteristic of anaplastic carcinoma. Anticancer Res 27: 2679–2683 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominsky SL, Tyler B, Sosnowski J, Brady K, Doucet M, Nell D, Smedley III JG, McClane B, Brem H, Sukumar S (2007) Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin as a novel-targeted therapeutic for brain metastasis. Cancer Res 67: 7977–7982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshikawa K, Osada H, Kozaki K, Konishi H, Masuda A, Tatematsu Y, Mitsudomi T, Nakao A, Takahashi T (2002) Significant up-regulation of a novel gene, CLCP1, in a highly metastatic lung cancer subline as well as in lung cancers in vivo. Oncogene 21: 2822–2828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothapalli R, Yoder SJ, Mane S, Loughran Jr TP (2002) Microarray results: how accurate are they? BMC Bioinformatics 3: 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, MacLeod TJ, Zhang Y, Waisman DM (2005) S100A10, annexin A2, and annexin a2 heterotetramer as candidate plasminogen receptors. Front Biosci 10: 300–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langaas M (2005) Estimating the proportion of true null hypotheses, with application to DNA microarray data. J R Stat Soc 67: 555–572 [Google Scholar]

- Lee W, Choi KS, Riddell J, Ip C, Ghosh D, Park JH, Park YM (2007) Human peroxiredoxin 1 and 2 are not duplicate proteins: the unique presence of CYS83 in Prx1 underscores the structural and functional differences between Prx1 and Prx2. J Biol Chem 282: 22011–22022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci G, Mrozek K, Bloomfield CD (2005) Molecular heterogeneity and prognostic biomarkers in adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics. Curr Opin Hematol 12: 68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiers I, Shanks JH, Bostwick DG (2007) Glutathione S-transferase pi (GSTP1) hypermethylation in prostate cancer: review 2007. Pathology 39: 299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldvay J, Jackel M, Paska C, Soltesz I, Schaff Z, Kiss A (2007) Distinct claudin expression profile in histologic subtypes of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 57: 159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin PJ (2005) Claudin proteins in human cancer: promising new targets for diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Res 65: 9603–9606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy R, Erlandsson K, Kumar D, Van Heertum R, Mann J, Parsey R (2007) Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of 11C-harmine in baboons. Nucl Med Commun 28: 748–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai H, Sugito N, Matsubara H, Tatematsu Y, Hida T, Sekido Y, Nagino M, Nimura Y, Takahashi T, Osada H (2007) CLCP1 interacts with semaphorin 4B and regulates motility of lung cancer cells. Oncogene 26: 4025–4031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nørsett KG, Laegreid A, Midelfart H, Yadetie F, Erlandsen SE, Falkmer S, Grønbech JE, Waldum HL, Komorowski J, Sandvik AK (2004) Gene expression based classification of gastric carcinoma. Cancer Lett 210: 227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada D, Kawamoto M, Koizumi K, Tanaka S, Fukuda Y (2003) Immunohistochemical study of the expression of drug-resistant proteins in large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 51: 272–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Örlefors H, Sundin A, Fasth KJ, Berg K, Langstrom B, Eriksson B, Bergstrom M (2003) Demonstration of high monoaminoxidase-A levels in neuroendocrine gastroenteropancreatic tumors in vitro and in vivo-tumor visualization using positron emission tomography with 11C-harmine. Nucl Med Biol 30: 669–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman I, Dai J, Mikhail M, Navarro D, Taneja SS, Lee P, Christos P, Shen R, Nanus DM (2006) Loss of neutral endopeptidase and activation of protein kinase B (Akt) is associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer 107: 2628–2636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez MA, Saul SH, Trojanowski JQ (1990) Neurofilament and chromogranin expression in normal and neoplastic neuroendocrine cells of the human gastrointestinal tract and pancreas. Cancer 65: 1219–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qvigstad G, Falkmer S, Westre B, Waldum HL (1999) Clinical and histopathological tumour progression in ECL cell carcinoids (‘ECLomas’). APMIS 107: 1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team (2004) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. InR Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna: Austria, ISBN 3-900051-00-3 http://www.r-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Shibata D, Mori Y, Cai K, Zhang L, Yin J, Elahi A, Hamelin R, Wong YF, Lo WK, Chung TK, Sato F, Karpeh Jr MS, Meltzer SJ (2006) RAB32 hypermethylation and microsatellite instability in gastric and endometrial adenocarcinomas. Int J Cancer 119: 801–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK (2005) Limma: linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor, Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R & Huber W (eds), pp 397–420. Springer: New York [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK, Michaud J, Scott H (2005) The use of within-array replicate spots for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics 21: 2067–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørhaug S, Steinshamn S, Haaverstad R, Nordrum IS, Martinsen TC, Waldum HL (2007) Expression of neuroendocrine markers in non-small cell lung cancer. APMIS 115: 152–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson TJ (2006) Prognostic and predictive factors in endocrine tumours. Histopathology 48: 629–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD (2002) A direct approach to false discovery rates. J Royal Stat Soc 64: 479–498 [Google Scholar]

- Sumitomo M, Shen R, Nanus DM (2005) Involvement of neutral endopeptidase in neoplastic progression. Biochim Biophys Acta 1751: 52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner SM, Austin JL, Leone G, Rush LJ, Plass C, Heinonen K, Mrozek K, Sill H, Knuutila S, Kolitz JE, Archer KJ, Caligiuri MA, Bloomfield CD, de La Chapelle A (2001) BAALC, the human member of a novel mammalian neuroectoderm gene lineage, is implicated in hematopoiesis and acute leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13901–13906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupenot L, Harper KL, O'Connor DT (2003) The chromogranin-secretogranin family. N Engl J Med 348: 1134–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toninello A, Pietrangeli P, De Marchi U, Salvi M, Mondovi B (2006) Amine oxidases in apoptosis and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1765: 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccella S, Cerutti R, Vigetti D, Furlan D, Oldrini R, Carnevali I, Pelosi G, La Rosa S, Passi A, Capella C (2006) Histidine decarboxylase, DOPA decarboxylase, and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 expression in neuroendocrine tumors: immunohistochemical study and gene expression analysis. J Histochem Cytochem 54: 863–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda J, Semba S, Chiba H, Sawada N, Seo Y, Kasuga M, Yokozaki H (2007) Heterogeneous expression of claudin-4 in human colorectal cancer: decreased claudin-4 expression at the invasive front correlates cancer invasion and metastasis. Pathobiology 74: 32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilar E, Salazar R, Perez-Garcia J, Cortes J, Oberg K, Tabernero J (2007) Chemotherapy and role of the proliferation marker Ki-67 in digestive neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer 14: 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafa LA, Palmer J, Fazli L, Hurtado-Coll A, Bell RH, Nelson CC, Gleave ME, Cox ME, Rennie PS (2007) Comprehensive expression analysis of L-dopa decarboxylase and established neuroendocrine markers in neoadjuvant hormone-treated vs varying Gleason grade prostate tumors. Hum Pathol 38: 161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick MR (2000) Neuroendocrine neoplasia. Current concepts. Am J Clin Pathol 113: 331–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu LL, Shi Y, Petrovics G, Sun C, Makarem M, Zhang W, Sesterhenn IA, McLeod DG, Sun L, Moul JW, Srivastava S (2003) PMEPA1, an androgen-regulated NEDD4-binding protein, exhibits cell growth inhibitory function and decreased expression during prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res 63: 4299–4304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadetie F, Laegreid A, Bakke I, Kusnierczyk W, Komorowski J, Waldum HL, Sandvik AK (2003) Liver gene expression in rats in response to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha agonist ciprofibrate. Physiol Genomics 15: 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang QS, Xia F, Gu SH, Yuan HL, Chen JZ, Yang QS, Ying K, Xie Y, Mao YM (2002a) Cloning and expression pattern of a spermatogenesis-related gene, BEX1, mapped to chromosome Xq22. Biochem Genet 40: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin DM, Peng V, Ngai J, Speed TP (2002b) Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nuclei Acids Res 30: e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MR, Colburn NH (2006) Fra-1 a target for cancer prevention or intervention. Gene 379: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Fogg DK, Waisman DM (2004) RNA interference-mediated silencing of the S100A10 gene attenuates plasmin generation and invasiveness of Colo 222 colorectal cancer cells. J Biol Chem 279: 2053–2062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.