Abstract

Fragile X syndrome is the most common cause of inherited mental retardation and the second most common cause of mental impairment after trisomy 21. It occurs because of a failure to express the fragile X mental retardation protein. The most common molecular basis for the disease is the abnormal expansion of the number of CGG repeats in the fragile X mental retardation 1 gene (FMR1). Based on the number of repeats, it is possible to distinguish four types of alleles: normal (5 to 44 repeats), intermediate (45 to 54), premutation (55 to 200), and full mutation (>200). Today, the diagnosis of fragile X syndrome is performed through a combination of PCR to identify fewer than 100 repeats and of Southern blot analysis to identify longer alleles and the methylation status of the FMR1 promoter. We have developed a methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification assay to analyze male fragile X syndrome cases with long repeat tracts that are not amplifiable by PCR. This inexpensive, rapid and robust technique provides not only a clear distinction between male pre- and full-mutation FMR1 alleles, but also permits the identification of genomic deletions, a less frequent cause of fragile X syndrome.

The fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene is directly associated with three distinct conditions: fragile X syndrome (the most common X-linked mental retardation syndrome), fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome, and premature ovarian failure.1,2 FMR1 encodes the fragile X mental retardation protein, an RNA-binding protein that shuttles from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it associates with polyribosomes and suppresses translation of a selective group of mRNAs to which it binds.3,4 It has been shown that dendrites are subject to fragile X mental retardation protein translation regulation in response to synaptic activity.5 FMR1 is highly conserved across species and contains a CGG trinucleotide repeat sequence of variable length in the 5′-untranslated region of the gene.6 Normal individuals carry 5 to 44 CGG repeats that are usually stably transmitted to the offspring. However, the CGG repeats can become unstable and expand in some families for reasons as yet unknown. Based on the size of the expansion, it is possible to distinguish four types of alleles: normal (5 to 44 repeats), intermediate (45 to 54 repeats), premutation (55 to 200 repeats), and full-mutation (>200 repeats) alleles. Intermediate and premutation alleles are distinguished through repeat instability and family history.7

Both premutation and full-mutation alleles result in FMR1 deregulation: Excess transcription occurs in the premutation setting and is associated with both fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome and premature ovarian failure; translational suppression of FMR1 mRNA occurs in the full-mutation setting and is strongly linked to fragile X syndrome.8,9,10,11 Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome patients display cognitive decline and generalized brain atrophy presenting beyond the fifth decade of life, and approximately 24% of premutation females experience premature ovarian failure. The prevalence of fragile X syndrome is approximately 1 in 4000 males and in 1 in 8000 females; it presents at around 36 months of age as developmental delay and eventually leads to cognitive impairment and other manifestations of the syndrome, such as hyperactivity and anxiety.12 The disease manifests itself most severely in males: IQ values of affected males range between 20 and 70, whereas one-third of female full-mutation patients have an IQ in the mildly retarded range and a corresponding mild-retardation phenotype.2

Although premutation patients exhibit elevated FMR1 mRNA levels, it has been demonstrated that fragile X mental retardation protein expression levels are diminished11 because of reduced translational efficiency presumably caused by the expanded CGG repeat in the 5′-untranslated region of FMR1 mRNA.13 However, it is in the setting of a full mutation that an almost complete absence of fragile X mental retardation protein occurs, and this absence is generally caused by transcriptional silencing of FMR1 through promoter hypermethylation.14,15 It is noteworthy that FMR1 promoter hypermethylation is absent in premutation patients.

Experimental determination of expansions greater than ∼100 repeats is difficult to achieve reliably with standard PCR methodology because of the very high GC content of the target sequence.16,17 Today, diagnosis of cases not amplifiable by standard PCR is therefore normally performed using Southern blot analysis, a low-resolution, time-consuming technique that requires a large amount of patient genomic DNA. Attempts made through modifications of the PCR technique, such as the use of dimethyl sulfoxide, 7-deaza-dGTP, and combinations of polymerases,18,19,20,21,22,23 have produced highly variable results, whereas studies that have investigated the promoter hypermethylation of full-mutation patients, mainly through the methylation-specific PCR technique, have made use of bisulfite-treated DNA, an inefficient transformation that requires large amounts of DNA and frequently does not work with poorer quality or paraffin-derived material.

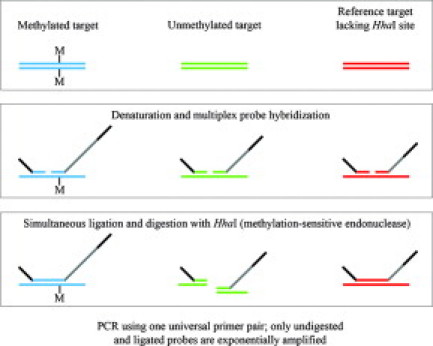

We have developed a novel assay using the methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification technique (MS-MLPA).24 MS-MLPA is based on the standard MLPA technique,25 in which up to 50 oligonucleotide probes are hybridized to a denatured DNA sample. However, each MS-MLPA probe is designed to span a recognition site for the methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease HhaI in its target-specific sequence. After a simultaneous ligation/digestion reaction of the probe/DNA complex using the Ligase-65 enzyme and HhaI, MLPA probes that are hybridized to unmethylated sites are digested and therefore not amplified (Figure 1). Comparison with an identical parallel reaction where the digestion step has been omitted reveals both relative copy number and methylation status of the analyzed sample. Here, we report our findings and demonstrate MS-MLPA to be an inexpensive, fast, and robust approach for the analysis of male fragile X syndrome cases that are not resolved by standard PCR.

Figure 1.

MS-MLPA principle: MS-MLPA probes hybridize in juxtaposition to completely denatured sample DNA. On completion of probe hybridization, ligation of the MS-MLPA probe oligonucleotides is combined with digestion of the probe/sample DNA hybrid complex using the methylation-sensitive restriction endonuclease HhaI. After the enzymatic digestion, probes juxtaposed to methylated regions will generate a signal in the subsequent PCR, whereas probes adjacent to unmethylated sites will be degraded and will generate no signal.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples

Anonymized DNA samples from fragile X patients (20 full-mutation males and four premutation males) and from four unaffected male controls were generously donated by Dr. Waltraud Friedl (Universitätsklinikum, Bonn, Germany), by Dr. Hans Gille (Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), and by Dr. Flora Tassone (University of California, Davis, CA). The fragile X status of each sample was independently confirmed through PCR/Southern blot analysis (Table 1). A commercially available mixture of the DNA of several male individuals, supplied by Promega (Leiden, The Netherlands), was also used as control DNA.

Table 1.

Patient Details and MS-MLPA Analysis Results

| Known fragile X status* | FMR1 D:U† | Mosaicism* (% full mutation alleles) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | |||

| 15 | F | 0.88 | N/A |

| 3421 | F | 0.77 | N/A |

| 4672 | F | 0.88 | N/A |

| 5575 | F | 0.64 | N/A |

| 21-02 | F | 0.85 | N/A |

| 24-05 | F | 0.80 | N/A |

| 46-05 | F | 0.93 | N/A |

| 80-05 | F | 0.80 | N/A |

| 88-05 | F | 0.83 | N/A |

| 111-04 | F | 0.96 | N/A |

| 118-05 | F | 0.87 | N/A |

| 128-02 | F | 0.90 | N/A |

| 139-05 | F | 0.96 | N/A |

| 146-05 | F | 0.89 | N/A |

| 200-05 | F | 0.71 | 18% |

| 237-04 | F | 0.68 | 15% |

| 300-03 | F | 0.83 | N/A |

| 343-04 | F | 0.85 | N/A |

| 403-04 | F | 0.65 | 46% |

| 525-05 | F | 0.72 | N/A |

| 13 | P | <0.05 | N/A |

| 10564 | P | <0.05 | N/A |

| 199-06 | P | <0.05 | N/A |

| 241-07 | P | <0.05 | N/A |

| Controls | |||

| Promega | N | <0.05 | N/A |

| 3 | N | <0.05 | N/A |

| C1 | N | <0.05 | N/A |

| C2 | N | <0.05 | N/A |

| C3 | N | <0.05 | N/A |

F, full mutation male; P, premutation male; N, unaffected control; N/A, not applicable.

As determined by Southern blot.

Each sample was repeated at least once; the range of FMR1 D:U ratios obtained for each sample differed by less than 10% without exception.

MS-MLPA Probe Design

The probe design was performed according to the guidelines described by Schouten et al,25 with the inclusion of an HhaI restriction site in the target recognition sequence of the methylation-specific probes. The developed fragile X mix contains 45 probes, divided as follows: 11 FMR1 probes, of which 5 are methylation specific; 14 FMR2 probes, of which 5 are methylation specific; 16 control probes, specific to different chromosome X sequences, 2 of which are methylation-specific and 14 of which are included for copy number quantification; 3 methylation-specific probes targeting unmethylated CpG islands elsewhere in the genome, included as digestion controls; and 1 chromosome Y-specific probe. Probe lengths and chromosomal locations can be found in Table 2, and information on probe sequences can be obtained from MRC-Holland (info@mlpa.com).

Table 2.

Description of Probes Used

| Chromosomal position |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (nucleotides) | MLPA probe | Control | FMR1 | FMR2 | HhaI sites |

| 64-70-76-82 | DQ-control fragments | ||||

| 88-92-96 | DD-control fragments | ||||

| 118 | Control probe NPK003-L0313 | Yq11 | |||

| 130 | Control probe 1690-L0423 | Xq11.2 | |||

| 136 | Control probe 2629-L3719 | Xq13.1 | |||

| 142 | FMR1 probe 2928-L3720 | Exon 16 | |||

| 148 | FMR2 probe 4036-L3198 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 154 | FMR2 probe 3734-L3194 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 160 | FMR1 probe 3722-L3182 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 166 | FMR1 probe 2927-L3721 | Exon 9 | |||

| 172 | Control probe 2901-L2295 | Xq26 | |||

| 178 | FMR2 probe 3740-L3200 | Exon 1 | |||

| 184 | Control probe 3644-L3057 | Xp22.3 | + | ||

| 190 | FMR1 probe 4037-L3722 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 196 | FMR1 probe 3727-L3187 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 202 | Control probe 2636-L2103 | Xq28.1 | |||

| 208 | FMR1 probe 3725-L3185 | + | |||

| 214 | FMR2 probe 4029-L2324 | Exon 20 | |||

| 220 | FMR1 probe 3728-L3188 | Exon 3 | |||

| 229 | Control probe 3047-L1030 | Xp21.2 | |||

| 238 | FMR2 probe 3516-L2322 | Exon 5 | |||

| 247 | FMR2 probe 3736-L3196 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 256 | FMR2 probe 3733-L3193 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 265 | Control probe 5875-L5275 | Xp22.3 | |||

| 274 | Control probe 5186-L4567 | Xp22.3 | |||

| 283 | FMR2 probe 0493-L0369 | Exon 3 | |||

| 292 | FMR1 probe 4031-L0833 | Exon 17 | |||

| 301 | FMR2 probe 3739-L3199 | Exon 4 | |||

| 310 | Control probe 5244-L4624 | Xq28.1 | |||

| 319 | Control probe 5251-L4631 | Xq28 | |||

| 328 | Control probe 2566-L2027 | Xp22.3 | |||

| 337 | FMR2 probe 2932-L2323 | Exon 11 | |||

| 346 | Methylation control probe 1709-L1276 | 15q26 | + | ||

| 355 | FMR2 probe 3741-L3201 | Exon 8 | |||

| 364 | FMR1 probe 3730-L3190 | Exon 7 | |||

| 373 | Control probe 2912-L2306 | Xp21.2 | |||

| 382 | FMR2 probe 3737-L3197 | Exon 1 | + | ||

| 391 | FMR1 probe 3726-L3186 | + | |||

| 400 | Control probe 3521-L2304 | Xq28.1 | + | ||

| 409 | FMR2 probe 3742-L3202 | Exon 10 | |||

| 418 | FMR1 probe 3731-L3191 | Exon 14 | |||

| 427 | Control probe 2923-L2317 | Xp22.4 | |||

| 436 | FMR2 probe 3743-L3203 | Exon 14 | |||

| 445 | Control probe 4138-L3495 | Xq28 | |||

| 454 | Methylation control probe 4046-L2172 | 3p24 | + | ||

| 463 | Methylation control probe 2260-L1747 | 3p22.1 | + | ||

| 472 | Control probe 2915-L2309 | Xq12 | |||

MS-MLPA Assay

The assay was performed largely as previously described24 and, unless otherwise specified, the reagents were provided by MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherland. Briefly, ∼100 ng of genomic DNA was denatured in a 5 μl Tris-EDTA buffer solution containing 10% glycerol and 20 mM NaOH for 10 minutes at 98°C. After the addition of SALSA MLPA buffer (1.5 μl) and MS-MLPA probes (1.5 μl) to the denatured sample, the mixture was heated for 1 minute at 95°C and for ∼16 hours at 60°C, allowing the probes to hybridize. After hybridization, a solution containing 3 μl of Ligase buffer A and 10 μl of H2O was added to the mixture at room temperature. The mixture was equally divided into two tubes, and while at 49°C, a mixture of 0.25 μl of Ligase-65, 5 U of HhaI (Promega), and 1.5 μl of Ligase buffer B diluted in H2O to 10 μl was added to one tube, whereas an equivalent mixture without HhaI was added to the second tube. Simultaneous ligation and digestion was then performed by incubation for 30 minutes at 49°C, followed by a 5 minute heat inactivation of the enzymes at 98°C. The ligation products were PCR amplified by the addition of 5 μl of each ligation mixture to a 20 μl PCR mixture containing PCR buffer, dNTPs, SALSA polymerase, and PCR primers (one unlabeled and one Cy5 labeled) at 60°C, followed by 35 cycles of amplification.

Fragment and Data Analysis

PCR products were analyzed using a Beckman-Coulter CEQ 8800 Genetic Analysis System (Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA), and the resulting data analysis was performed using the free Excel-based Coffalyser program, available at http://www.mlpa.com/coffalyser/. Each MS-MLPA reaction was performed at least in duplicate, and samples with incomplete digestion as identified by the digestion control probes were repeated.

Results

Visual inspection of the electropherograms depicted in Figure 2 clearly illustrates the difference in the methylation status of the FMR1 promoter between the three sample categories analyzed in this study. For both the Promega male control DNA and case 10564 (premutation patient), the peaks corresponding to all HhaI-containing probes are absent in the digested electropherograms (Figure 2, B and D) while remaining present in the undigested samples (Figure 2, A and C). This encompasses not only the FMR2 methylation-specific probes (Figure 2, curved arrows) and digestion control probes (Figure 2, arrowheads) but also the FMR1 methylation-specific probes (Figure 2, straight arrows), indicative of lack of methylation in all of these regions. The images for case 4672 (full-mutation patient), however, reveal the presence of FMR1 peaks in both undigested and digested samples (Figure 2, E and F), indicative of methylation in the FMR1 promoter region; conversely, the absence of FMR2 and digestion control peaks in the digested sample (Figure 2F) when compared with its undigested counterpart (Figure 2E) indicates that these regions remain unmethylated, as expected. Of note, FMR2 methylation-specific probes have been used in this study as internal controls for X chromosome methylation.

Figure 2.

Electropherograms depicting the differences in FMR1 and FMR2 peaks in each of the three male patient groups: Promega control (A and B), premutation patient (C and D), and full-mutation patient (E and F). All five FMR1 peaks are missing in both the Promega control and the premutation HhaI-digested samples (B and D) and present in the full-mutation HhaI-digested sample (F), indicative of FMR1 promoter hypermethylation only in the full-mutation patient; all five FMR2 peaks are missing from the HhaI-digested samples of all three groups (B, D, and F), indicative of lack of FMR2 promoter hypermethylation; all three control peaks showed complete digestion. Straight arrows, methylation-specific FMR1 probes; curved arrows, methylation-specific FMR2 probes; arrowheads, digestion control probes.

Determination of the methylation status of the FMR1 gene in all samples was achieved using the Coffalyser analysis software. This analysis tool calculated the normalized ratios of HhaI digested to undigested (D:U) peaks for each of the five FMR1 methylation-specific probes present in each sample. In an attempt to reduce the complexity of the analysis and to minimize the intersample variation in the pattern of FMR1 promoter hypermethylation, the average of the ratios of the five FMR1 methylation-specific probes was taken to be the sample FMR1 D:U.

As expected, the analysis showed all of the male unaffected individuals (N = 4, in addition to the Promega male control DNA) and the premutation males (N = 4) to have an FMR1 D:U ratio of <0.05, whereas the full-mutation males (N = 20) presented values ranging from 0.64 to 0.93 (average of 0.82), clearly demonstrating FMR1 promoter hypermethylation (Tables 1 and 3). Furthermore, three of the full-mutation males, determined by Southern blot analysis to be mosaics (Table 1), were correctly diagnosed by MS-MLPA as having full-mutation alleles. In an additional demonstration of the reliability of the technique in examining male mosaic samples, a dilution series of full-mutation patient 4672 demonstrated that MS-MLPA detected FMR1 promoter hypermethylation in all full-mutation DNA concentrations tested (100, 80, 60, 40, 20, 10, and 5%), attesting the sensitivity of the technique (Table 4).

Table 3.

Average Ratios Observed in Different Study Groups

| Sample type | No. of cases | Average FMR1 D:U (range) | Theoretical FMR1 D:U |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male unaffected controls | 5 | <0.05 | 0 |

| Male premutation cases | 4 | <0.05 | 0 |

| Male full mutation cases | 20 | 0.82 (0.64 to 0.93) | 1 |

Table 4.

Dilution Series of DNA from Patient 4672 (Full Mutation Patient)

| Percentage of 4672 DNA* | FMR1 D:U |

|---|---|

| 100 | 0.88 |

| 80 | 0.69 |

| 60 | 0.48 |

| 40 | 0.27 |

| 20 | 0.22 |

| 10 | 0.14 |

| 5 | 0.11 |

| 0 | <0.05 |

Dilution (when applicable) of 4672 DNA performed with Promega male control DNA.

Discussion

Conventional PCR-based techniques allow for the accurate detection of only up to ∼100 CGG repeats in the FMR1 gene. They provide a reliable method for distinguishing normal FMR1 individuals from those carrying intermediate and, in some cases, premutation alleles. When PCR techniques fail, Southern blot analysis is typically the method of choice for differentiating premutation from full-mutation individuals. However, Southern blot analysis requires large amounts of patient DNA and is time consuming. There is therefore a need for the development of a fast and reliable method that enables the distinction between premutation and full-mutation cases, acting as a complement to the standard PCR FMR1 mutation detection and thereby permitting the characterization of all samples within the fragile X syndrome context.

MS-MLPA has previously demonstrated its robustness and reproducibility in a number of previous studies.24,26,27,28 Here, we have used the technique to confirm the mutation status of several fragile X male patients and unaffected controls through analysis of FMR1 promoter methylation. This method relies on the crucial distinction between FMR1 premutation and full-mutation DNA: premutation alleles display no promoter hypermethylation, whereas in full-mutation patients, the promoter region is hypermethylated to varying degrees (Figure 2).12,29 In addition, unlike any other method currently used for fragile X diagnosis, MS-MLPA can reveal the presence of chromosomal aberrations, such as deletions or amplifications, within the investigated loci, because the probe mix used in this study contains several probes spanning the length of FMR1.

Fragile X is significantly more prevalent among males, and typically, the disease is more severe in this group because of the disruption of the only existing copy of FMR1. Our analysis revealed a very clear distinction between male premutation and full-mutation patients, indicative of the robustness of MS-MLPA for diagnosis of this fragile X group. The technique was also attempted on female patients but because of the complexity conferred by the presence an imprinted X chromosome, a small percentage of borderline cases could not be successfully analyzed.

As expected, all of the male unaffected individuals and the male premutation cases showed an FMR1 D:U ratio of <0.05, consistent with the fact that no FMR1 promoter hypermethylation was observed in the sole male X chromosome. By contrast, the 20 full-mutation male patients had an FMR1 D:U ratio average of 0.82, lower than the expected value of 1 but consistent with the mosaicism commonly observed in the FMR1 locus29 and clearly indicative of FMR1 promoter hypermethylation (Tables 1and 3; Figure 2). The three cases determined by Southern blot analysis as displaying mosaicism all presented lower than average FMR1 D:U ratios (Table 1).

A further test of the reliability of the technique in detecting a wide range of levels of full-mutation DNA, emulating various mosaicism settings, was successfully performed. In a dilution series of DNA from patient 4672 (full-mutation male), the presence of as little as 5% of full-mutation DNA sufficed to detect FMR1 promoter hypermethylation and thus the presence of full-mutation alleles (Table 4).

Noteworthy, one of the premutation cases (241-07) possessed a very high level of CGG repeats (close to 200), indicating the clear distinction in the methylation levels of the FMR1 promoter between premutation and full-mutation alleles, as detected by MS-MLPA.

In the majority of diagnostic laboratories, Southern blot analysis is still the technique of choice to elucidate the number of FMR1 CGG repeats in samples not resolved by conventional PCR. Because of the large amounts of DNA required and because the technique is labor intensive and time consuming, attempts have been made at replacing Southern blot analysis with modifications of the conventional PCR. Results have, however, been highly variable, largely because of the difficulty in amplifying such GC-rich regions. Accurate detection of the fragile X syndrome is crucial, not only because of its relatively high incidence (it is the most common inherited cause of mental retardation), but because of the phenotypical variation of disease presentation, making clinical diagnosis sometimes difficult. In addition, diagnosis of a serious condition such as fragile X syndrome based on a negative PCR result is highly undesirable. Here, we present an inexpensive, fast, and robust technique that provides a clear distinction between premutation and full-mutation FMR1 alleles in male patients, and we therefore conclude that MS-MLPA is a very useful complement to conventional PCR in correctly diagnosing fragile X syndrome in this patient group. Additionally, the methylation level of FMR1 may provide an indication as to the presence of FMR1 mRNA in full-mutation cases, making these patients the target of therapies aimed at increasing translational efficiency, rather than transcriptional activity, of FMR1.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Waltraud Friedl (Universitätsklinikum, Bonn, Germany), Dr. Hans Gille (Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and Dr. Flora Tassone (University of California, Davis, CA) for the kind donation of patient material.

References

- 1.Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. The fragile-X premutation: a maturing perspective. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:805–816. doi: 10.1086/386296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terracciano A, Chiurazzi P, Neri G. Fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:32–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laggerbauer B, Ostareck D, Keidel EM, Ostareck-Lederer A, Fischer U. Evidence that fragile X mental retardation protein is a negative regulator of translation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:329–338. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z, Zhang Y, Ku L, Wilkinson KD, Warren ST, Feng Y. The fragile X mental retardation protein inhibits translation via interacting with mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2276–2283. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.11.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bear MF, Huber KM, Warren ST. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang FP, Eussen BE, van Ommen G-JB, Blonden LAJ, Riggins GJ, Chastain JL, Kunst CB, Galjaard H, Caskey CT, Nelson DL, Oostraa BA, Warren ST. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;65:905–914. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90397-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolin SL, Brown WT, Glicksman A, Houck GE, Jr, Gargano AD, Sullivan A, Biancalana V, Brondum-Nielsen K, Hjalgrim H, Holinski-Feder E, Kooy F, Longshore J, Macpherson J, Mandel JL, Matthijs G, Rousseau F, Steinbach P, Vaisanen ML, von Koskull H, Sherman SL. Expansion of the fragile X CGG repeat in females with premutation or intermediate alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:454–464. doi: 10.1086/367713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Heinrichs W, Tassone F, Wilson R, Hills J, Grigsby J, Gage B, Hagerman PJ. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Grigsby J, Zhang L, Brunberg JA, Greco C, Des Portes V, Jardini T, Levine R, Berry-Kravis E, Brown WT, Schaeffer S, Kissel J, Tassone F, Hagerman PJ. Fragile X premutation tremor/ataxia syndrome: molecular, clinical, and neuroimaging correlates. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:869–878. doi: 10.1086/374321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Chamberlain WD, Hagerman PJ. Transcription of the FMR1 gene in individuals with fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97:195–203. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<195::AID-AJMG1037>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Taylor AK, Gane LW, Godfrey TE, Hagerman PJ. Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: a new mechanism of involvement in the fragile-X syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:6–15. doi: 10.1086/302720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garber K, Smith KT, Reines D, Warren ST. Transcription, translation and fragile X syndrome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Primerano B, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman P, Amaldi F, Bagni C. Reduced FMR1 mRNA translation efficiency in fragile X patients with premutations. RNA. 2002;8:1482–1488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pieretti M, Zhang FP, Fu YH, Warren ST, Oostra BA, Caskey CT, Nelson DL. Absence of expression of the FMR-1 gene in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;66:817–822. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90125-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verheij C, Bakker CE, de Graaff E, Keulemans J, Willemsen R, Verkerk AJ, Galjaard H, Reuser AJ, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra BA. Characterization and localization of the FMR-1 gene product associated with fragile X syndrome. Nature. 1993;363:722–724. doi: 10.1038/363722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saluto A, Brussino A, Tassone F, Arduino C, Cagnoli C, Pappi P, Hagerman P, Migone N, Brusco A. An enhanced polymerase chain reaction assay to detect pre- and full mutation alleles of the fragile X mental retardation 1 gene. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:605–612. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60594-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strom CM, Crossley B, Redman JB, Buller A, Quan F, Peng M, McGinnis M, Fenwick RG, Jr, Sun W. Molecular testing for Fragile X Syndrome: lessons learned from 119,232 tests performed in a clinical laboratory. Genet Med. 2007;9:46–51. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31802d833c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown WT, Nolin S, Houck G, Jr, Ding X, Glicksman A, Li SY, Stark-Houck S, Brophy P, Duncan C, Dobkin C, Jenkins E. Prenatal diagnosis and carrier screening for fragile X by PCR. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64:191–195. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960712)64:1<191::AID-AJMG34>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddad LA, Mingroni-Netto RC, Vianna-Morgante AM, Pena SD. A PCR-based test suitable for screening for fragile X syndrome among mentally retarded males. Hum Genet. 1996;97:808–812. doi: 10.1007/BF02346194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamdan H, Tynan JA, Fenwick RA, Leon JA. Automated detection of trinucleotide repeats in Fragile X Syndrome. Mol Diagn. 1997;2:259–269. doi: 10.1054/MODI00200259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hećimović S, Vlasic J, Barisic L, Markovic D, Culic V, Pavelic K. A simple and rapid analysis of triplet repeat diseases by expand long PCR. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2001;39:1259–1262. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2001.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houdayer C, Lemonnier A, Gerard M, Chauve C, Tredano M, de Villemeur TB, Aymard P, Bonnefont JP, Feldmann D. Improved fluorescent PCR-based assay for sizing CGG repeats at the FRAXA locus. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:397–402. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connell CD, Atha DH, Jakupciak JP, Amos JA, Richie K. Standardization of PCR amplification for fragile X trinucleotide repeat measurements. Clin Genet. 2002;61:13–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nygren AO, Ameziane N, Duarte HM, Vijzelaar RN, Waisfisz Q, Hess CJ, Schouten JP, Errami A. Methylation-specific MLPA (MS-MLPA): simultaneous detection of CpG methylation and copy number changes of up to 40 sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schouten JP, McElgunn CJ, Waaijer R, Zwijnenburg D, Diepvens F, Pals G. Relative quantification of 40 nucleic acid sequences by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dikow N, Nygren AO, Schouten JP, Hartmann C, Kramer N, Janssen B, Zschocke J. Quantification of the methylation status of the PWS/AS imprinted region: comparison of two approaches based on bisulfite sequencing and methylation-sensitive MLPA. Mol Cell Probes. 2007;21:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murthy SK, Nygren AO, El Shakankiry HM, Schouten JP, Al Khayat AI, Ridha A, Al Ali MT. Detection of a novel familial deletion of four genes between BP1 and BP2 of the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome critical region by oligo-array CGH in a child with neurological disorder and speech impairment. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;116:135–140. doi: 10.1159/000097433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Procter M, Chou LS, Tang W, Jama M, Mao R. Molecular diagnosis of Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes by methylation-specific melting analysis and methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1276–1283. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.067603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tassone F, Hagerman PJ. Expression of the FMR1 gene. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;100:124–128. doi: 10.1159/000072846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]