Abstract

A Polycomb-Group (PcG) complex, FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT SEED (FIS), represses endosperm development in Arabidopsis thaliana until fertilization occurs. The Hieracium genus contains apomictic species that form viable seeds asexually. To investigate FIS function during apomictic seed formation, FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT ENDOSPERM (FIE), encoding a WD-repeat member of the FIS complex, was isolated and downregulated in sexual and apomictic Hieracium species. General downregulation led to defects in leaf and seed development, consistent with a role in developmental transitions and cell fate. PcG-like activity of Hieracium FIE was also supported by its interaction in vitro with the Arabidopsis CURLY LEAF PcG protein. By contrast, specific downregulation of FIE in developing seeds of sexual Hieracium did not result in autonomous endosperm proliferation but led to seed abortion after cross-pollination. Furthermore, in apomictic Hieracium, specific FIE downregulation inhibited autonomous embryo and endosperm initiation, and most autonomous seeds displayed defective embryo and endosperm growth. Therefore, FIE is required for both apomictic and fertilization-induced seed initiation in Hieracium. Since Hieracium FIE failed to interact with FIS class proteins in vitro, its partner proteins might differ from those in the FIS complex of Arabidopsis. These differences in protein interaction were attributed to structural modifications predicted from comparisons of Arabidopsis and Hieracium FIE molecular models.

INTRODUCTION

Seed initiation in sexually reproducing flowering plants requires signals arising from a double fertilization event that occurs in the embryo sac found in the ovule of the flower (Weterings and Russell, 2004). The egg cell and the central cell of the multicellular embryo sac are the progenitors of the embryo and endosperm in the seed, respectively. One sperm cell fuses with the egg to generate the zygote and initiate embryo development, while the other fuses with the central cell to initiate endosperm development. The central cell contains two polar nuclei, and these nuclei either fuse prior to fertilization, as in Arabidopsis thaliana, or fuse together with the sperm nucleus during fertilization, as in maize (Zea mays; Olsen, 2004). Fertilization of the central cell in diploid plants therefore produces triploid endosperm containing a two maternal (2m) to one paternal (1p) genome ratio in contrast with the 1m:1p genome ratio observed in the embryo. In the absence of double fertilization, the egg and central cell in sexually reproducing plants remain in a quiescent state and degrade during senescence of the flower, suggesting that signaling processes are required to activate development of the fertilization products (Chaudhury et al., 2001).

Plants can also form seeds asexually by apomixis. In the case of the daisy-like apomict Hieracium, apomixis is a dominant trait and deviates from sexual reproduction at three key steps: meiosis is avoided prior to embryo sac formation (a process known as apomeiosis), and embryo and endosperm development is fertilization independent. The embryo maintains the genotype of the maternal parent, therefore showing that maternally derived information can completely drive the entire process of apomictic seed formation (Bicknell and Koltunow, 2004). Apomixis is not a novel pathway superimposed over sexual reproduction. Analysis of apomixis in Hieracium using reproductive marker genes has shown that once each of the key steps of apomixis are initiated, both the sexual and apomictic gene expression programs share common elements and regulators (Tucker et al., 2003). It has been suggested that apomixis results from a deregulation of the sexual program as a result of mutation, altered epigenetic regulation, or both (Koltunow and Grossniklaus, 2003).

Repressive chromatin remodeling complexes resembling those of the Polycomb group (PcG) of Drosophila melanogaster and animals control many aspects of plant growth and development (Reyes and Grossniklaus, 2003). One such complex in Arabidopsis, called FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT SEED (FIS), mediates the mitotic arrest of the central cell prior to fertilization (for review, see Berger et al., 2006). FIS complex genes encode the WD40 domain protein FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT ENDOSPERM (FIE; Ohad et al., 1999), the SUPPRESSOR OF VARIEGATION-ENHANCER OF ZESTE-TRITHORAX (SET) domain–containing protein MEDEA (MEA/FIS1) (Grossniklaus et al., 1998; Luo et al., 2000), the WD40 protein MULTICOPY SUPPRESSOR OF IRA1 (MSI1; Köhler et al., 2003), and the VEFS domain protein FIS2 (Luo et al., 2000). In vitro interaction studies have shown that FIE interacts with MEA and MSI1, and FIS2 interacts with MEA (Luo et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2006). Loss-of-function mutations in any of these FIS genes result in uncontrolled central cell proliferation and seed coat development in the absence of fertilization, leading to the formation of seed-like structures that eventually abort. However, seeds derived from the same loss-of-function mutants also abort after fertilization, showing defects in embryo and endosperm growth (Grossniklaus et al., 1998; Ohad et al., 1999; Luo et al., 2000). The FIS complex of Arabidopsis therefore appears to have two functions in seed development. The first is to repress endosperm development prior to fertilization and the second to promote normal embryo and endosperm development following fertilization.

It has been proposed that egg cell arrest prior to fertilization in Arabidopsis is controlled by MSI1 and other factors independent of the FIS pathway because mutations in MSI1 lead to autonomous divisions of the egg cell that trigger nonviable embryo formation (Guitton and Berger 2005; Berger et al., 2006). Association of the Arabidopsis homolog of the mammalian tumor suppressor RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED (RBR) protein with FIS and MSI1 function has also been speculated because it interacts in vitro with both MSI1 and FIE (Katz et al., 2004), and mutations in RBR lead to autonomous cell proliferation in the embryo sac (Ingouff et al., 2006). However, the identity of the proliferating cells is ambiguous. Unlike animal PcG complexes, the composition of plant PcG complexes is flexible, and they seem less stable during development, as their repressive action can be relieved by specific environmental and developmental stimuli, such as cold and fertilization (Reyes and Grossniklaus, 2003). In this respect, double fertilization is thought to initiate as yet unknown signal transduction cascades that disassemble repressive complexes in the egg and central cell of Arabidopsis to activate transcription of downstream seed development genes, thereby maintaining a requirement for a paternal contribution during seed formation.

Little is known about the composition and function of plant PcG complexes during seed development in species other than Arabidopsis. The Hieracium genus contains both sexual and apomictic species. In apomictic species, the egg and central cell lack the quiescent arrest observed in sexual plants, and fertilization is not required for seed development. Given that apomixis might be a deregulated sexual pathway, one hypothesis is that Hieracium homologs of putative repressive complexes may not be expressed or might be misregulated in apomicts facilitating autonomous seed initiation. To examine this possibility, two Hieracium FIS complex homologs, MSI1 and FIE, in addition to RBR were isolated from ovaries and found to be highly conserved between sexual and apomictic species. In vitro protein interactions were examined between the Hieracium proteins and Arabidopsis FIS class members. Hieracium FIE function was examined in transgenic sexual and apomictic plants by RNA interference (RNAi)-induced downregulation of the gene using constitutive and gametophyte-specific promoters. Our results indicate that FIE activity is required for embryo and endosperm proliferation and growth in sexual and apomictic Hieracium.

RESULTS

Isolation of FIE, MSI1, and RBR from Ovaries of Sexual and Apomictic Hieracium

Hieracium develops multiple florets on a floral head or capitulum. Each floret has one ovary containing a single ovule subtending all of the other floral organs (Figure 1A). Full-length cDNAs encoding putative FIE, MSI1, and RBR proteins were isolated from ovaries of sexual and apomictic Hieracium species (H. pilosella and H. piloselloides, respectively) containing mature gametophytes. Despite repeated attempts, a Hieracium FIS2 cDNA was not detected even though a cDNA for the homolog of Arabidopsis EMBRYONIC FLOWER2, a member of the FIS2 family, was found previously (Chaudhury et al., 2001). Isolation of MEA was not attempted in this study. The Hieracium FIE, MSI1, and RBR protein sequences are highly conserved between sexual and apomictic plants (>97.1%) and share significant conservation with homologous sequences from Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa), and maize (Table 1).

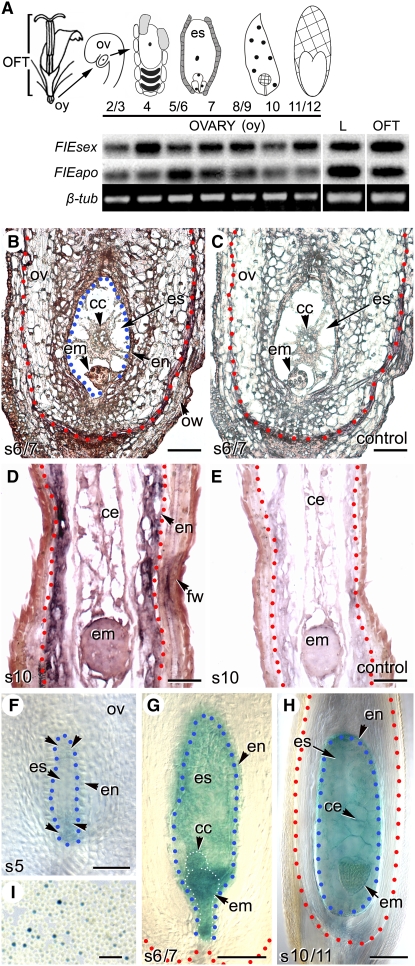

Figure 1.

Expression Analysis of FIEapo, FIEsex, and AtMEA:GUS in Hieracium.

(A) Schematic diagram showing a Hieracium floret with the ovary (oy) subtending the other floral tissues (OFT). RT-PCR analysis showing FIEsex and FIEapo expression in leaves (L) throughout development of the ovary and in other floral tissues. β-tubulin (β-tub) was used as an internal control, and three replicates were performed. Events occurring in the ovule (ov), embryo sac (es), and seeds at various stages of capitulum formation are schematically represented above the stage numbers (Koltunow et al., 1998).

(B) Analysis of the spatial distribution of FIEapo transcripts in early seeds of the apomict by in situ hybridization. FIEapo mRNA is detected throughout the seed, including the ovule (ov), at low levels (purple/red signal), and is found in the central cell (cc), early embryo (em), endothelium (en), and ovary wall (ow) of the embryo sac (es). Red dots indicate the border between the ovule and the ovary, and blue dots outline the embryo sac.

(C) Sense control for (B).

(D) FIEsex mRNA was generally distributed in sexual Hieracium seeds, including the embryo (em), cellular endosperm (ce), endothelium (en), and fruit wall (fw).

(E) Sense control for (D). Stages are indicated at the bottom left in (B) to (E). Bars = 50 μm in (B) to (E).

(F) to (I) At MEA:GUS expression in apomictic ([F] and [G]) and sexual (H) Hieracium plants is detected in female gametophytes and early seed structures and in pollen (I). The abbreviations are as described in (B) to (E). In (F), the unlabeled arrowheads indicate the location of four nuclei. Stages are indicated at the bottom left, and the blue dots in (F) to (H) indicate the border of the female gametophyte and the ovule. Bars = 30 μm in (F) to (H) and 100 μm in (I).

Table 1.

Comparison of Percentage of Amino Acid Identities between Sequences Isolated from Apomictic and Sexual Hieracium with Homologous Sequences from Arabidopsis, O. sativa, and Z. mays

| FIE

|

MSI1

|

RBR

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEX | At | Zm | SEX | At | Os | SEX | At | Zm | |

| APO | 99.7% | 73.7% | 74.2% | 99.7% | 88.4% | 84.3% | 97.1% | 66.4% | 57.8% |

| SEX | 73.5% | 74.9% | 88.6% | 84.3% | 66.1% | 57.5% | |||

| At | 67.0% | 85.0% | 58.0% | ||||||

APO, apomictic Hieracium; SEX, sexual Hieracium.

The Hieracium plants used in this study are polyploids with the sexual species being tetraploid and the apomict triploid. Genomic analysis of the isolated genes suggested that few copies were present in the genomes of sexual and apomictic plants, although multiple alleles were detected by PCR, consistent with the polyploid nature of the plants. However, RT-PCR analysis suggested that only one sequence encoding the Hieracium FIE WD-repeat protein was expressed in each plant. The FIE sequence from the apomict (FIEapo) differed from that of the sexual (FIEsex) species by 32 bp over the total length of 1110 bp, resulting in only one conservative amino acid substitution at position 159 (Glu in FIEapo to Gln in FIEsex; see Supplemental Figure 1A online). Both Hieracium FIE proteins share significant conservation with FIE from Arabidopsis (Table 1; see Supplemental Figure 1A online), with the majority of amino acid differences found outside of the seven predicted WD40 protein domains. FIE genomic sequences were isolated from sexual and apomictic Hieracium plants and compared with each expressed cDNA to determine the complexity of the gene family (see Supplemental Figure 1C and Supplemental Data Set 1 online). The genomes of the apomictic and sexual plants appear to contain at least four and two noncoding alleles, respectively, with in-frame stop codons. Only one pair of highly conserved alleles, FIEapo-1/FIEapo-2 and FIEsex-1/FIEsex-2, matched the expressed cDNA sequences in each plant (see Supplemental Figure 1C), which is consistent with the observation that plant PcG proteins are encoded by small gene families (Makarevich et al., 2006). Since sexual and apomictic Hieracium appear to express a single FIE sequence and FIE from Arabidopsis has been shown to interact in vitro with the MEA and MSI1 FIS complex members and also with RBR, we examined FIE function during seed initiation in sexual and apomictic Hieracium.

FIE Gene Expression Is Similar in Sexual and Apomictic Hieracium

FIE transcripts were detected by RT-PCR in leaves, other floral tissues, and ovaries throughout embryo sac and early seed development in sexual and apomictic Hieracium plants (Figure 1A). In situ hybridization was used to examine the spatial localization of FIE transcripts in Hieracium ovaries and in developing seeds. The patterns were very similar in sexual and apomictic plants. For example, during the early events of seed initiation in the apomict, FIE mRNA was present at very low levels in the central cell and early embryo and also in surrounding maternal tissues compared with sense controls (Figures 1B and 1C). Figures 1D and 1E show that at later stages in the sexual Hieracium plant, FIE mRNA was also found at low levels in developing globular embryos and cellular endosperm and in the ovary wall of the developing seed. This contrasts with the in situ localization pattern of FIE transcripts in Arabidopsis that are reported to be restricted to cells in the embryo sac and absent in maternal tissues of the developing Arabidopsis seed (Spillane et al., 2000). Arabidopsis FIE promoter-gene fusions have shown variable expression patterns dependent upon the construct (Yadegari et al., 2000), but expression of a genomic Arabidopsis FIE reporter fusion has not yet been reported. Hieracium FIE appears to have constitutive expression in ovaries of sexual and apomictic species. As there appears to be no difference in the level of FIE expression in sexual and apomictic Hieracium plants (Figure 1A), it is unlikely that the level of FIE expression is the cause of autonomous seed development in the apomict.

Hieracium FIE Plays Roles in Vegetative and Inflorescence Growth and Interacts with Arabidopsis CURLY LEAF in Vitro

To examine if FIE is required for plant growth in Hieracium, the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV35S) was used to downregulate FIE expression in apomictic plants via RNAi-mediated silencing using a construct termed 35S:hpHFIE. Previous work showed that the CaMV35S promoter is active in vegetative and inflorescence tissues and during certain, but not all, stages of ovary and embryo sac development in Hieracium (e.g., stages 2, 3, and 7 in Figure 1A; Koltunow et al., 2001). Two independent 35S:hpHFIE transgenic plants were recovered where Hieracium FIE expression was significantly downregulated in leaves (Table 2), and in these plants the inflorescence internodes displayed reduced elongation resulting in a stunted flowering plant stature relative to flowering controls (Figure 2A).

Table 2.

Analysis of Hieracium FIE Expression, Seed Set, and Germination in Sexual and Apomictic Hieracium Plants Transformed with RNAi Constructs to Downregulate FIE Constitutively (35S:hpHFIE) and in Gametophytes (AtMEA:hpHFIE)

| Transgene Copy Number | Hieracium FIE Level | Number of Black Fruit/Capitulum (%)

|

Number Viable Seedlings/Capitulum (%)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | Unpollinated | Cross-Pollinated | Unpollinated | Cross-Pollinated | ||

| 35S:hpHFIE | ||||||

| Control Apomict | 0 | 100b | 24.7 (75) [n = 20]c | 17.8 (54) | ||

| 5 | NDd | 20b | 18.1 (54) [n = 14] | 10.4 (31) | ||

| 7 | ND | 10b | 1.4 (4) [n = 25] | 1.0 (3) | ||

| AtMEA:hpHFIE | ||||||

| Control Sexual | 0 | 100e | 16.3 ± 6.4 (35) [n = 3] | 27.0 ± 6.4 (58) [n = 4] | 10.3 (22) | 23.0 (49) |

| 5 | 2 | 78e | 3.0 ± 4.1 (4) [n = 5] | 23.3 ± 5.9 (31) [n = 4] | 2.4 (3) | 14.5 (19) |

| 14 | 2 | 45e | 0.4 ± 0.9 (1) [n = 5] | 15.8 ± 2.6 (22) [n = 4] | 0.0 | 6.3 (9) |

| 18 | 2 | 64e | 1.2 ± 0.8 (2) [n = 5] | 5.3 ± 1.0 (10) [n = 4] | 1.0 (2) | 4.3 (8) |

| AtMEA:hpHFIE | ||||||

| Control Apomict | 0 | 100e | 23.6 ± 4.0 (73) [n = 5] | 18.0 (54) | ||

| 15.1 | 3 | 72e | 9.6 ± 2.8 (19) [n = 5] | 1.0 (2) | ||

| 17.0 | 4 | 48e | 19.4 ± 3.4 (36) [n = 5] | 2.8 (5) | ||

| 18.0 | 2 | 51e | 5.2 ± 2.4 (19) [n = 5] | 1.2 (2) | ||

| 19.0 | 3 | 64e | 8.6 ± 2.9 (17) [n = 5] | 0.2 (0.4) | ||

APO, apomictic Hieracium; SEX, sexual Hieracium.

All black fruit were plated for germination, and the number germinated was divided by the total number of capitula.

Percentage of expression in leaf relative to the wild type.

n = number of capitula examined.

ND, not determined.

Percentage of expression in ovules relative to the wild type. Hieracium FIE expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR using cDNA from ovules at stage 6 of capitulum development.

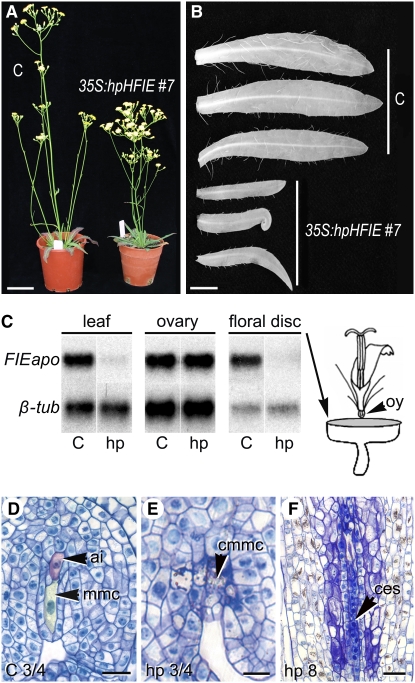

Figure 2.

Analysis of the General Downregulation of FIEapo in Apomictic Hieracium Using the 35S:hpHFIE RNAi Construct.

(A) Transgenic lines (right) are stunted, with shorter inflorescence internode lengths compared with untransformed apomictic Hieracium controls (C, left). Bar = 8 cm.

(B) Leaves of transgenic plants are generally shorter than untransformed control leaves of the same age and curl at the sides and tips. Bar = 1 cm.

(C) RT-PCR analysis of FIEapo transcripts in leaf, ovary (oy), and floral disc tissues from control (C) and 35S:hpHFIE (hp) plants relative to a β-tubulin (β-tub) internal control. Two replicates were performed.

(D) to (F) Cytological analysis of ovules using semithin sectioning. ai, aposporous initial (shaded in red); mmc, megaspore mother cell (shaded in yellow); cmmc, collapsed megaspore mother cell; ces, collapsed embryo sac. Bars = 20 μm.

(D) Apomictic control.

(E) Transgenic at same stage as (D).

(F) Collapsed embryo sac in transgenic plant. Stages are indicated at the bottom left.

Many of the leaves were smaller and often curled relative to those of the same age in untransformed control plants (Figure 2B). Curled leaf phenotypes are also observed in Arabidopsis when mutations occur in the plant PcG SET-domain gene CURLY LEAF (CLF) or when expression of its interacting partner Arabidopsis FIE (At FIE) is reduced in vegetative tissues (Goodrich et al., 1997; Katz et al., 2004). We therefore tested whether Hieracium FIE could interact in vitro with Arabidopsis CLF (At CLF) using yeast two-hybrid analysis. Positive in vitro interactions were observed between At CLF and FIE from both sexual and apomictic Hieracium, although colony growth was not as vigorous relative to that found in the At CLF and At FIE interaction (Figure 3A). These functional observations connect Hieracium FIE with known FIE PcG function in vegetative tissues of Arabidopsis and further suggest that the curled leaf phenotype in the transgenic Hieracium plants might relate to reduced levels of Hieracium FIE protein available for appropriate interaction with a putative Hieracium CLF protein in leaf tissues.

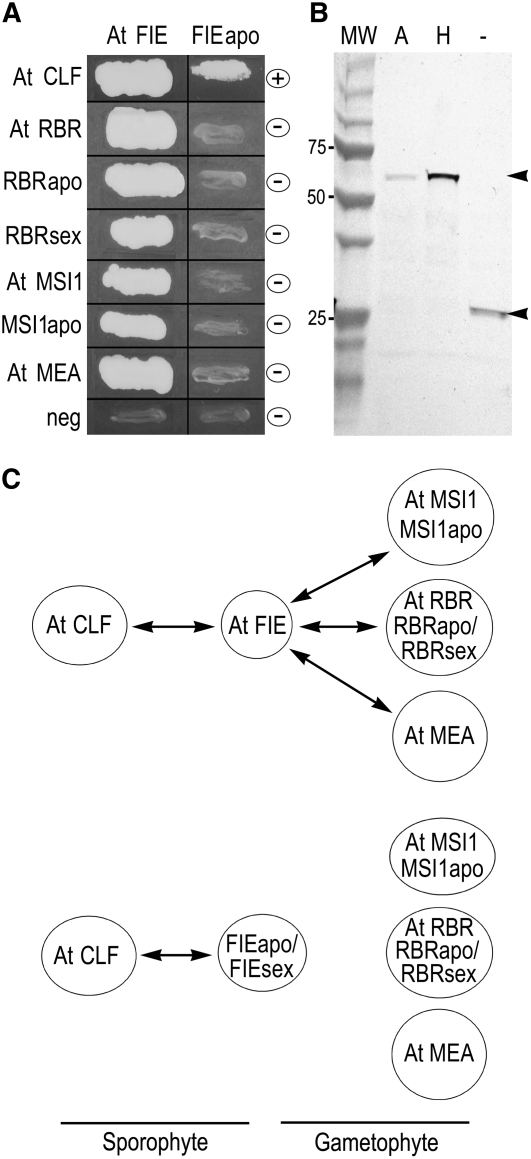

Figure 3.

At FIE and Hieracium FIE Interactions with PcG Proteins in Yeast Two-Hybrid Assays.

(A) FIE protein sequences from Arabidopsis (At FIE) and sexual and apomictic Hieracium (FIEsex and FIEapo) were used as bait and tested for interaction with other Hieracium and Arabidopsis FIS protein members. This panel shows interaction results for At FIE and FIEapo from the apomict, and growth indicates positive interaction (+), while no interaction (for FIEapo) is indicated with a minus symbol (−).

(B) Protein gel blot analysis confirming the presence of AtFIE (A; 67 kD) and FIEapo (H; 67 kD) protein in yeast protein extracts relative to the empty vector control (−; 25 kD).

(C) Schematic diagram summarizing the results of the yeast two-hybrid assays. Positive interactions are indicated by double-headed arrows.

Seed Number and Viability Is Reduced in Transgenic 35S:hpHFIE Plants

Seed initiation and germination were also reduced in the apomictic Hieracium plants transformed with 35S:hpHFIE relative to untransformed controls (Table 2). The apomict is self-incompatible (Bicknell and Koltunow, 2004), and autonomous initiation of either the embryo or the endosperm correlates with ovary enlargement and deposition of pigment in the differentiating fruit wall resulting in black fruit (BF) formation. Germination is used to test for seed viability as abortion is common during seed development in Hieracium species (Koltunow et al., 1998).

RT-PCR analysis of ovaries from the 35S:hpHFIE plants at embryo sac maturity (stage 6/7) indicated that Hieracium FIE levels were not significantly reduced relative to control plants (Figure 2C). This was not unexpected as we have previously found that the CaMV35S promoter is not active at this stage in Hieracium ovaries (Koltunow et al., 2001). FIE was, however, clearly downregulated in floral disc tissue subtending the ovary (Figure 2C). Cytological analysis of the most seed sterile plant (#7, Table 2) at early stages of ovule development where the CaMV35S promoter is active indicated that defects frequently occurred in the initiation of sexual and apomictic pathways, and at later stages, abortion of embryo sac and seed formation was evident (Figures 2D to 2F). The observed defects in seed formation were concluded to be caused by a combination of direct and indirect effects reflecting the reduction of FIE expression in a wide range of floral and vegetative tissues and suggest that FIE plays a role in seed development in Hieracium. Further analysis of this role required targeted downregulation of Hieracium FIE in the female gametophyte and developing seeds.

Specific Downregulation of FIE in Ovules of Sexual Hieracium Does Not Stimulate Central Cell Proliferation

We hypothesized that if FIE is part of a complex repressing central cell proliferation in sexual Hieracium, then reduced FIE expression in the embryo sac would compromise complex formation and result in an autonomous central cell proliferation phenotype similar to that found in Arabidopsis FIS complex mutants. As FIE is expressed in most Hieracium tissues, we targeted downregulation of FIE specifically to the embryo sac to test this hypothesis directly. A promoter fragment from the Arabidopsis MEA gene was used to direct the downregulation of Hieracium FIE by RNAi-mediated gene silencing using a hairpin construct designated AtMEA:hpHFIE. The selected MEA sequence directs linked β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity to developing embryo sacs during the mitotic events of embryo sac formation (Figure 1F) and to the egg, central cell, embryo, and endosperm of sexual and apomictic Hieracium (Figures 1G and 1H) until the late heart stage of embryogenesis, after which expression is no longer detected in the seed. The MEA sequence also directs expression to pollen grains (Figure 1I), but GUS activity is not detected in other parts of the Hieracium plant. This pattern contrasts with that observed in Arabidopsis using the same MEA sequence fused to GUS where expression is not observed in the egg, embryo, or pollen grains (Luo et al., 2000).

Three independent, hemizygous transgenic tetraploid sexual H. pilosella lines containing AtMEA:hpHFIE were characterized (Table 2). Ovules at embryo sac maturity were physically extracted from surrounding ovary tissue, and quantitative RT-PCR was used to examine the level of Hieracium FIE expression relative to that in ovules at the same stage extracted from control plants. In contrast with the inability of the 35S:hpHFIE construct to downregulate Hieracium FIE in ovaries at this stage (Figure 2C), these AtMEA:hpHFIE plants displayed significantly reduced FIE mRNA expression in ovules that ranged from 45 to 78% of that found in controls (Table 2, Figure 4A). This range is experimentally consistent with that likely to be expected for a downregulation of FIE in the embryo sac, given that the Hieracium embryo sac can occupy up to half of the volume of the ovule depending on the stage of development and that not all cells of the ovule express FIE to the same degree (Figure 1). Hieracium FIE was not downregulated in leaves of these transgenic plants, and they resembled untransformed control plants with respect to vegetative and floral growth and plant stature.

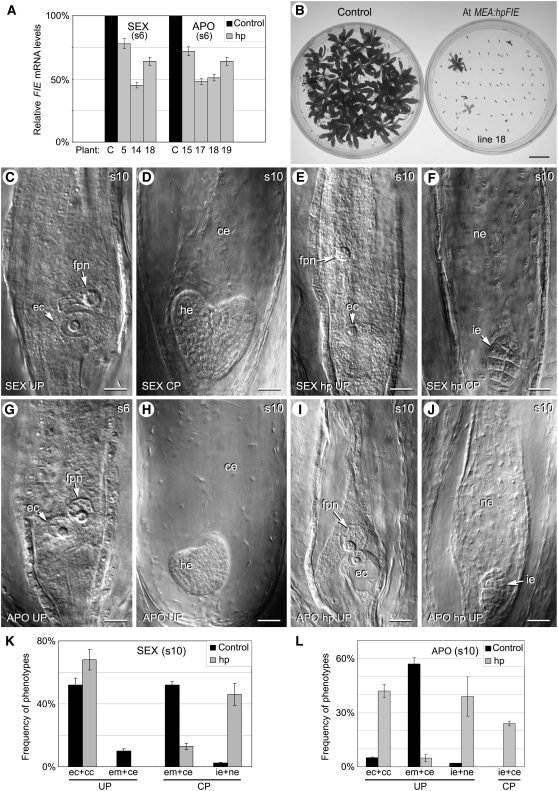

Figure 4.

Analysis of the Downregulation of FIE in Embryo Sacs of Sexual and Apomictic Hieracium Using the AtMEA:hpHFIE RNAi Construct.

(A) Hieracium FIE expression levels in ovules from AtMEA:hpHFIE transgenic lines of sexual (lines 5, 14, and 18) and apomictic (lines 15, 17, 18, and 19) plants relative to 100% FIE expression levels in control plants, as determined by quantitative RT-PCR analysis and three biological replicates. (FIE is expressed throughout the Hieracium ovule, but the downregulation construct is targeted to cells of the embryo sac.) Error bars indicate sd.

(B) A comparison of seed germination in cross-pollinated control sexual plants and seeds from transgenic line 18 containing the RNAi construct. Bar = 15 mm.

(C) to (F) Differential interference contrast images of cleared ovaries and seeds from unpollinated (C) or cross-pollinated (D) sexual Hieracium plants and unpollinated (E) or cross-pollinated (F) transgenic sexual Hieracium plants containing the RNAi hairpin (hp) construct.

(G) and (H) Cleared ovules and seeds of untransformed apomictic Hieracium.

(I) and (J) Apomictic Hieracium containing the RNAi construct. Numbers in top right of each panel represent stages of capitulum development. ce, cellular endosperm; ec, egg cell; fpn, fused polar nuclei; he, heart stage embryo; ie, irregular embryo; ne, nuclear endosperm. Bars = 50 μm in (C) to (J).

(K) Frequency of seed phenotypes observed in cleared ovules at stage 10 of capitulum development in three control sexual Hieracium plants compared with the three sexual lines containing the RNAi construct (hp) when unpollinated (UP) or when cross-pollinated (CP).

(L) Seed phenotypes in cleared ovaries of three untransformed apomictic Hieracium control plants compared collectively with the four transgenic lines containing AtMEA:hpHFIE. In (K) and (L), at least 100 ovaries were scored per plant at stage 10, and the bars in the graph represent the mean for plants analyzed per treatment with error bars showing the sd. Phenotype abbreviations: ec+cc, egg cell and fused central cell nucleus; em+ce, embryo with cellular endosperm; ie+ne, irregular embryo with nuclear endosperm; ie+ce, irregular embryo with cellular endosperm.

Sexual plants containing AtMEA:hpHFIE displayed reduced seed set and germination (Table 2, Figure 4B). Sexual Hieracium species are generally self-incompatible (Bicknell and Koltunow, 2004), and seed set is usually dependent upon cross-pollination. However, plants can be partially self-compatible under warm growth conditions, and this was evident by seed set in control plants that were not cross-pollinated (Table 2). Targeting the downregulation of Hieracium FIE to pollen and embryo sacs of transgenic sexual lines did not increase the percentage of BF in unpollinated plants as would be expected from the induction of autonomous seed development. Rather, fewer BF formed, indicating a decrease in self-fertilization due to reduced pollen and/or embryo sac viability (Table 2). The percentage of BF only increased following cross-pollination in both control and transgenic plants, indicating that fertilization was still required for seed initiation.

Seed germination per capitulum was reduced in both unpollinated and cross-pollinated transgenic plants (Table 2, Figure 4B). Cytological analysis indicated that the mitotic events of embryo sac formation were comparable in transgenic plants and in untransformed controls, suggesting that Hieracium FIE does not play a discernable role in this process. Alterations in embryo sac development were first identified at embryo sac maturity and during the early events of seed initiation in transgenic sexual plants. Cleared ovules of control plants at embryo sac maturity (Figure 4C) display mature eggs and adjacent fused polar nuclei that develop into embryos and nuclear then cellular endosperm, respectively, following fertilization (Figure 4D). In the transgenic Hieracium lines where FIE downregulation was targeted to the embryo sac, the fused central cell nucleus frequently failed to migrate close to the egg, which could influence the success of fertilization (Figure 4E). After both self- and cross-pollination, aborted seeds containing irregular globular embryos and nuclear endosperm were observed by clearing (Figure 4F).

Control and transgenic plants were scored at stage 10 of capitulum development, with or without cross-pollination, to compare the percentage of mature and arrested embryo sacs and the morphology of initiated and arrested seed structures. Figure 4K shows these comparative data where the scores for the three transgenic sexual plant lines have been pooled and averaged. In ovules of control sexual plants, 50% of the embryo sacs examined at stage 10 contained fused polar nuclei positioned close to the egg cell, and 10% had initiated seed formation as a result of partial self-compatibility. The remaining ovules were sterile, consistent with previous observations (Koltunow et al., 1998). Following cross-pollination, the frequency of seeds with globular or heart-stage embryos and cellular endosperm increased (Figure 4K). By contrast, in transgenic sexual plants containing AtMEA:hpHFIE, a greater number of arrested eggs and central cells (∼67%; Figure 4K) were observed in plants that were not cross-pollinated, and in approximately half of these, the fused central cell nucleus failed to migrate toward the egg cell (Figure 4E). In transgenic plants cross-pollinated with an untransformed plant, >40% of seeds contained small, irregular aborted embryos where the endosperm failed to cellularize even when seeds were observed at later stages (Figure 4K). Based on the germination data, the majority of these irregular embryos failed to develop further (Table 2). Viable seedlings derived from sexual transgenic lines did not contain the transgene, indicating segregation of the AtMEA:hpHFIE construct.

These data collectively show that central cell proliferation is not stimulated in sexual Hieracium when the downregulation of FIE expression is targeted to developing embryos sacs. Hieracium FIE activity in the embryo sac appears to be required for positioning of the central cell nucleus prior to fertilization and also for the early events of fertilization-induced embryo and endosperm development.

FIE Is Required for Fertilization-Independent Seed Initiation in Apomictic Hieracium

As FIE appears to be required for functional embryo and endosperm formation in sexual Hieracium, we also examined FIE function in apomictic Hieracium. Unlike sexual Hieracium, the egg and polar nuclei of the apomict do not enter into a quiescent state at embryo sac maturity. Embryo and endosperm initiate together, but in a stochastic manner among ovules, typically before the flower opens. We determined that fusion of polar nuclei was a prerequisite for autonomous endosperm initiation from cytological observations (Figure 4G) and flow cytometry of 178 individual seeds from the apomict, which showed that the residual endosperm located in the aleurone of the seed had double the relative ploidy of the embryo. Comparisons between fertilization-induced and autonomous endosperm development in Hieracium indicated that there are differences in the spatial patterning of the early nuclear endosperm divisions in the apomict relative to those in the sexual plant. Endosperm nuclei and associated cytoplasm clumped together in the apomict with irregular spacing between nuclei; however, this normalized with increasing nuclear divisions and at cellularization the endosperm of the apomict resembled that of the sexual plant (see Supplemental Figure 2 online).

Four independent apomictic Hieracium plants containing AtMEA:hpHFIE were generated with reduced FIE expression in ovules (Table 2, Figure 4A). These plants had normal vegetative and floral growth habit, but all showed significantly reduced capacity to develop autonomous seeds, and seed viability was low compared with untransformed control plants (Table 2). Cytological examination of the transgenic plants showed that the initiation of apomixis and the subsequent events of embryo sac formation occurred normally. In contrast with the rapid development of autonomous embryo and endosperm in control apomictic plants (Figure 4H), both autonomous embryo and endosperm formation were significantly inhibited in transgenic plants where Hieracium FIE was downregulated in ovules. Cytological events were scored at stage 10 for the four transgenic lines, and the pooled and averaged data are shown in Figure 4L. In 40% of the ovaries from transgenic lines examined at stage 10, embryo and endosperm had not initiated (Figures 4I and 4L), compared with only 5% in the control, untransformed apomict (Figure 4L). Another 40% of the examined ovaries from transgenic plants contained small irregular embryos and nuclear endosperm (Figure 4J), while seed formation proceeded normally in only ∼5% of ovaries. Pollination of the transgenic lines with either a sexual plant or an untransformed apomict plant increased endosperm cellularization, but most embryos arrested at an irregular globular stage (Figure 4L).

Therefore, somewhat surprisingly, the maintenance of normal levels of FIE expression in the ovule and embryo sac of apomictic Hieracium appears to be required for the successful initiation of fertilization-independent seed development. Hieracium FIE expression is also required for the subsequent events of embryo formation and endosperm cellularization in the apomict, which is also the case for sexual Hieracium and Arabidopsis.

Hieracium FIE Inhibits Central Cell Proliferation in the Arabidopsis fie-2 Mutant

Downregulation of FIE in Hieracium ovules indicated that this gene does not have an obvious role in repressing central cell proliferation in sexual plants but does have a positive role promoting seed initiation in sexual and apomictic plants. To test whether Hieracium FIE has roles distinct to Arabidopsis FIE, we examined if FIE from apomictic Hieracium (FIEapo) could complement the Arabidopsis fie-2 mutant. Homozygous fie-2 lines cannot be generated due to embryo lethality. Following fertilization in fie-2 heterozygous mutants, 50% of the ovules initiate embryo development but arrest at the mid-heart stage (Ohad et al., 1996). The same MEA promoter sequence used to target the downregulation of FIE in Hieracium embryo sacs (Luo et al., 2000) was used to drive the expression of a full-length FIEapo cDNA in transformed Arabidopsis. In contrast with Hieracium, the MEA sequence in Arabidopsis only enables linked gene expression in the central cell and nuclear endosperm domains. Therefore, in the case of complementation, expression of functional Hieracium FIEapo protein from a single copy of AtMEA:FIEapo in emasculated fie-2/+ lines was expected to halve the number of ovules exhibiting central cell proliferation, but it was not certain if it would rescue the embryo phenotype.

Pollen from the fie-2/+ mutant was crossed with wild-type controls and plants containing the AtMEA:FIEapo transgene. Two F2 lines containing the fie-2 mutation that were heterozygous for the AtMEA:FIEapo transgene were identified, emasculated, observed 3 d later for autonomous central cell development, and compared with emasculated fie-2/+ control lines without the transgene. In control lines, 30 flowers were emasculated, and an average of 21% (sd ± 4.8%) of the ovules analyzed contained proliferating central cells, reflecting previous reports for this allele at 3 d after emasculation (Ohad et al., 1996). In the complementation lines, an average of 11% (sd ± 2.4%) of ovules from 40 emasculated flowers showed autonomous proliferation of the central cell. This represents the expected 50% reduction in the number of ovules containing autonomous endosperm.

By contrast, FIEapo expression from the MEA promoter could not correspondingly restore embryo viability in self-pollinated complementation lines, and the expected 50% reduction in embryo lethality was not observed. In self-pollinated lines, the proportion of aborted seeds per silique was similar in both control (49.2% ± 1.4%) and complementation lines (49.7% ± 2.2%). This could possibly stem from a lack of AtMEA:FIEapo expression in the cells where it is required for embryo development. However, since expression conferred by MEA closely mimics the central cell and endosperm-specific expression of Arabidopsis FIE:FIE-GFP, which is sufficient to restore embryo viability in fie-1 (Kinoshita et al., 2001), it seems more likely to be due to functional differences between Hieracium FIE and At FIE.

Together, these data indicate that despite the apparent absence of a central cell repressive function for Hieracium FIE in sexual Hieracium, the introduction of HFIEapo into Arabidopsis fie-2 is able to restore the requirement for fertilization for central cell proliferation. This suggests that Hieracium may not require a FIS complex to maintain central cell arrest, and/or FIE might be differentially recruited to functional complexes in Arabidopsis and Hieracium.

Hieracium FIE Does Not Interact Directly with FIS Complex Proteins in Vitro

To further examine interaction properties of the Hieracium FIE proteins from sexual and apomictic plants, yeast two-hybrid assays were used to assess their potential to bind with other members of the FIS complex in vitro. At FIE interacted as previously reported with At MSI1, At RBR, and At MEA (Figure 3A). At FIE also interacted with RBR and MSI1 from apomictic and sexual Hieracium plants (Figure 3A). By contrast, Hieracium FIEapo and FIEsex failed to interact with any of the aforementioned Arabidopsis and Hieracium proteins (Figure 3A) even though FIE protein was confirmed to be present in the yeast extracts used in these experiments (Figure 3B). Figure 3C provides a summary of the yeast two-hybrid data with respect to the likely functional interactions in sporophytic and gametophytic tissues. The inability of FIEapo to interact with the other FIS complex members in vitro suggests that the reduction in central cell proliferation in the fie-2 mutant by AtMEA:FIEapo may not occur via direct interaction with the conventional set of Arabidopsis FIS class members. Since Hieracium FIE can interact with At CLF in vitro but not with At MEA, it is possible that another SET-domain protein facilitates the function of FIEapo in repressing fie-2 central cell proliferation.

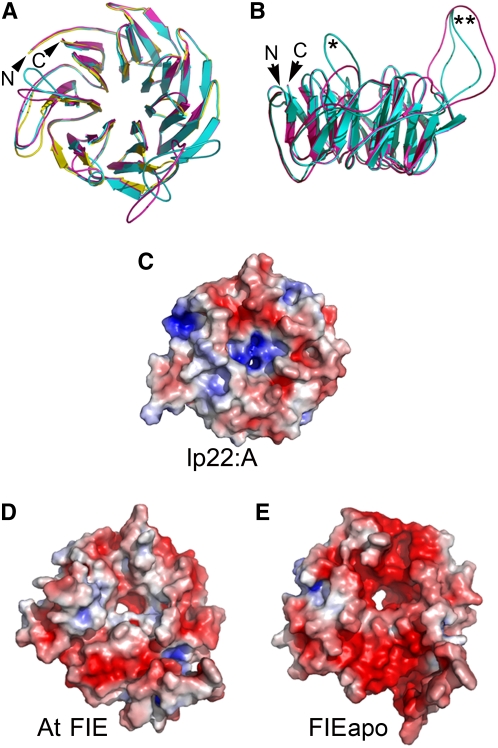

At FIE and Hieracium FIE Proteins Show Differences in Disposition of Surface Loops That May Alter Protein Interaction and Function

Structural models of the At FIE and Hieracium FIE proteins were constructed and compared to examine if there were differences in their tertiary structures that might influence protein–protein interactions. Molecular modeling was conducted with Hieracium FIEapo sequence because the single amino acid change in the FIEsex sequence was conservative with respect to protein structure and resulted from a change in the third (wobble) residue of the codon. The crystal structure of human β-trcp1-skp1-β-catenin protein (protein database accession code 1p22, chain A; or lp22:A) was used as the template for the molecular modeling of the At FIE and FIEapo proteins.

Figures 5A and 5B show front and side views, respectively, of the superimposed models of the At FIE, FIEapo, and 1p22:A proteins. All proteins contain a series of highly conserved β-sheets folded into a seven-bladed β-propeller structure. The major structural differences stem from the position of protein loop elements that connect each blade of the propeller and protrude from the propeller surface, providing interacting sites on the surface of the protein. Two conspicuous differences in loop disposition between the At FIE and FIEapo proteins were observed, and these are marked with asterisks in Figure 5B. They were due to repositioning of nucleophilic residues and also their replacement by uncharged polar residues in the two proteins. For example, in the loop marked by a double asterisk (Figure 5B), the motif beginning at amino acid 217-WTDDP in At FIE was replaced by WEGSP in FIEapo. A more pronounced series of substitutions was present in the motif LHLSSV beginning at position 301 in At FIE, which was substituted by FHYNAA in FIEapo (single asterisk in Figure 5B). The repositioning of nucleophilic residues is likely to lead to changes in the distribution of electrostatic potentials.

Figure 5.

Three-Dimensional Molecular Models of At FIE and Hieracium FIEapo Proteins.

(A) Superposition of the At FIE (cyan) or FIEapo (magenta) models on the template crystal structure of 1p22:A (yellow) over the Cα backbone positions showing a β-propeller fold with secondary structural elements. The root mean square deviation values were 0.76 and 0.64 Å for 286 and 283 amino acid residues superposed over the Cα carbon positions of 1p22:A and At FIE or FIEapo pairs, respectively. N and C indicate NH2 and COOH termini, respectively.

(B) The side view of the At FIE or FIEapo 3D models rotated ∼90° through the x axis with respect to the view in (A). Two different loop dispositions marked with asterisks are discussed in the text. N and C indicate NH2 and COOH termini, respectively.

(C) to (E) Charge distributions mapped onto molecular surfaces of the template human 1p22:A structure (C) and onto the molecular models of At FIE (D) or FIEapo (E). Red and blue patches indicate electropositive (contoured at +5 kT e−1) and electronegative (−5 kT e−1) regions, respectively, and white patches indicate electroneutral regions. The orientations of structures are identical to their orientations in (A).

Figures 5C to 5E show the calculated distributions of electrostatic potentials on the surfaces of the β propellers lp22:A, At FIE, and FIEapo, respectively. Compared with the template crystal 1p22 structure, the FIEapo and At FIE models display extensive acidic or positively charged regions on their surfaces, indicated in red, although the distributions of positively charged and neutral regions differ between the two models. The observed differences in the dispositions of protein loops and of electrostatic potentials on the surface of the At FIE and FIEapo models are the most likely features to influence protein interactions and might explain why the Hieracium FIEapo and FIEsex proteins do not interact with the other FIS class members in vitro.

DISCUSSION

General Comparison of Hieracium and Arabidopsis FIE Form and Function

Similar to its Arabidopsis counterpart, Hieracium FIE is expressed in multiple tissues and participates in different aspects of the plant life cycle (Figures 1 and 2). General downregulation of FIE in Hieracium confirmed that it has a role in the regulation of leaf morphology, inflorescence, and seed growth. Similarly, global reductions in FIE activity in Arabidopsis lead to reduced seed fertility and leaf and floral defects (Goodrich et al., 1997; Katz et al., 2004). Both Hieracium FIE and At FIE WD-repeat proteins lack recognizable DNA binding or catalytic domains and, similar to most of the identified WD-repeat proteins, are therefore likely to function as components in multiprotein complexes (Li and Roberts, 2001). Genetic, molecular, and biochemical analysis has shown that At FIE participates in a number of different PcG complexes during the life cycle of Arabidopsis, with different stimuli including cold and fertilization influencing repressive complex disassembly (Kinoshita et al., 2001; Reyes and Grossniklaus, 2003; Katz et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2006). The similar functions of Hieracium and Arabidopsis FIE during general development are likely to be due to a conserved mechanism of PcG-mediated repression of genes controlling the timing of developmental transitions and cell fate.

When Hieracium FIE and At FIE protein sequences are compared, significant sequence conservation is evident in the WD40 protein domains of both proteins with the majority of differences evident in the intervening regions outside the repeats (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). The structural models showed significant conservation between Hieracium FIE and At FIE with respect to the seven-bladed β-propeller structure, which makes up the core of the protein, and differences in the surface loops generated from the intervening regions that are predicted to alter the surface charge of the protein (Figure 5). Site-directed mutagenesis in the Drosophila PcG homolog of FIE, EXTRA SEX COMBS (ESC), has shown that the surface loops arising from amino acid sequences outside the WD repeats play critical roles in ESC protein function. It has been suggested that these regions might mediate physical interaction with ESC partner proteins (Ng et al., 1997). The proposed differences in protein structure between Hieracium FIE and At FIE might therefore explain why Hieracium FIE is able to interact with the SET domain–containing At CLF PcG protein in vitro but unable to interact with the other At FIS protein members in yeast two-hybrid assays.

The lack of Hieracium FIE interaction in vitro with At MEA (also a SET domain–containing protein) is not surprising given that At MEA originated from a recent genomic duplication event specific to the Brassicaceae lineage (Spillane et al., 2007). However, since the main biochemical role of WD proteins appears to be binding and arranging other proteins into functional complexes, it seems likely that the observed reduction in central cell proliferation in the fie-2 mutant by Hieracium FIEapo is due to the formation of a repressive complex and might be related to an ability of Hieracium FIE to bind other proteins in Arabidopsis that facilitate the rescue. SWINGER, another SET domain protein from Arabidopsis that shows higher homology to At CLF1 than to At MEA, is an attractive candidate because it is expressed in the central cell and exhibits partial functional overlap with MEA (Wang et al., 2006). Identification of the nature and identity of the proteins that partner Hieracium FIE and their targets during seed development in both Hieracium and Arabidopsis is required to further address this question.

Hieracium FIE Is Essential for Early Seed Initiation in Sexual and Apomictic Plants

It has been demonstrated that in the absence of fertilization in Arabidopsis the FIS complex acts to repress proliferation of the central cell, and it has been proposed that an alternative repressive complex inhibits the proliferation of the egg cell (Berger et al., 2006). A second role of the FIS complex is to promote normal embryo and endosperm development following fertilization (Grossniklaus et al., 1998; Ohad et al., 1999; Luo et al., 2000; Sørensen et al., 2001). However, in Arabidopsis, if egg cell–specific fertilization occurs and the polar nuclei are not fertilized, the endosperm proliferates autonomously, indicating that a positive signal from the fertilized egg can cue endosperm proliferation. The seeds initiated in this manner are nonviable (Nowack et al., 2006), but small viable Arabidopsis seeds can be formed when egg-specific fertilization occurs in a fis mutant background where, for example, either FIE, FIS2, or MEA function is defective (Nowack et al., 2007). These surprising data, together with the observed rescue of seed viability when fis mutants are pollinated with a hypomethylated plant (Luo et al., 2000; Vinkenoog et al., 2000), suggest that although the FIS genes might play a postfertilization role in Arabidopsis seed formation, they are not absolutely essential for embryo and endosperm growth when deviations from the normal double fertilization events occur. The signaling cascades occurring in the ovule upon fertilization in Arabidopsis, or any plant species, are not known, nor are all of the targets of fertilization products that activate seed development. It may be that gene targets and pathways initiated following fertilization with hypomethylated sperm cells or when signals are solely derived from a fertilized egg in Arabidopsis differ from those stimulated during double fertilization.

Hieracium FIE was our primary focus for functional analyses because At FIE interacts with several At FIS proteins during seed development (Luo et al., 2000; Köhler et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006). General downregulation of Hieracium FIE by 35S:hpHFIE confirmed that the gene is essential for multiple developmental processes during plant growth (Figure 2), similar to Arabidopsis FIE. However, specific downregulation of FIE in Hieracium embryo sacs via the AtMEA:hpHFIE construct alluded to differences between the Arabidopsis and Hieracium genes. Targeted downregulation of FIE in the embryo sacs of sexual Hieracium failed to stimulate autonomous central cell development despite a clear reduction in FIE mRNA levels (Figure 4). This could be due to Hieracium FIE playing an essential role in embryo sac development prior to the stage when autonomous endosperm initiates or due to Hieracium FIE having no function in the repression of central cell proliferation. The former seems unlikely, since only subtle defects were observed in embryo sac morphology at maturity and the gametophytic structures were still receptive to fertilization (Figure 4). It seems more likely that the repressive role of FIE in the central cell may be one of the few FIE functions not conserved between Arabidopsis and Hieracium. The analysis of FIE in Hieracium indicates that it is required early for successful embryo and endosperm formation in both sexual and apomictic plants. Pollination of FIE downregulated sexual Hieracium plants was required to activate seed initiation, yet significant seed abortion occurred by the early globular stage and endosperm failed to cellularize in most seeds. Surprisingly, autonomous embryo and endosperm formation was significantly inhibited in apomictic plants containing AtMEA:hpHFIE, and seed development arrested early with endosperm failing to cellularize. Interestingly, endosperm cellularization was restored in aborted seeds of the apomictic AtMEA:hpHFIE plants after cross-pollination. Endosperm cellularization does not occur during either fertilization-induced or autonomous central cell proliferation in Arabidopsis fie mutants, and embryo development in fertilized fie mutants progresses to the heart stage before embryo arrest (Ohad et al., 1996; Vinkenoog et al., 2000). FIE might therefore be involved in the transition from the syncytial to the cellular phase of endosperm development in Hieracium and Arabidopsis.

Collectively, these data suggest that FIE is likely to be a poor candidate for the synthesis of apomixis in crop plants as, depending on the crop, its downregulation might not lead to autonomous endosperm proliferation and/or may induce seed abortion. Analysis of FIS function in maize would be instructive, where FIE-like genes (Danilevskaya et al., 2003) and a SET domain homolog similar to MEA have been isolated and shown to be regulated by genomic imprinting (Haun et al., 2007).

Alternative Pathways Preventing Central Cell Proliferation and Activating Seed Initiation in Sexual and Apomictic Plants?

One major question arising from this study is that if FIE function in repressing central cell development is not conserved in Hieracium, what prevents the initiation of endosperm development in the absence of fertilization in sexual Hieracium species and allows the induction of autonomous endosperm development in apomictic species? It is possible that an alternative repressive mechanism acts in Hieracium to maintain the central cell in a quiescent state until fertilization, and this could be disrupted in apomictic species. Alternatively, no repressive complex may be present and positive signals from fertilization might stimulate proliferation of the central cell. In apomictic species, these signals could arise from autonomous development of the unfertilized, unreduced egg.

In apomictic Hieracium, the LOSS OF PARTHENOGENESIS locus (LOP) enables the initiation of autonomous embryo development (Catanach et al., 2006). LOP might function to stimulate a signal transduction cascade that activates autonomous embryogenesis that may in turn stimulate endosperm proliferation. Alternatively, LOP may coordinately activate both embryo and endosperm development. Both possibilities are consistent with the relatively coordinated timing of embryo and endosperm formation observed during autonomous seed development.

In pseudogamous apomicts, such as gamma grass (Tripsacum), bahia grass (Paspalum), and St. Lucia grass (Brachiaria), embryogenesis is also autonomous, but central cell proliferation is blocked and requires fertilization for activation. It is possible that adequate activating signals do not arise from the apomixis-stimulated proliferating egg cell in these species or that the activation signal cannot effectively disable a repressive central cell complex to allow endosperm formation and viable seed development. Further analysis of the partners of FIE in sexual and apomictic Hieracium species, together with functional analyses of FIS genes and complexes formed in pseudogamous apomicts, seem to be logical next steps toward testing these activation hypotheses and also for further examination of internal signaling between the egg and central cell in apomicts.

METHODS

Plant Material and General Procedures

A triploid accession of apomictic Hieracium piloselloides (D3; 3x = 2n = 27) and a tetraploid sexual biotype of Hieracium pilosella (4x = 2n = 36) were used for experiments. Cross-pollination of the sexual plant and transgenic derivatives was performed using either D3 or the tetraploid apomict Hieracium caespitosum (C4D; 4x = 2n = 36; Catanach et al., 2006). The sexual plant or C4D was used to cross-pollinate transgenic derivatives of D3. All plants were maintained in culture as stocks from individual characterized source plants, and the developmental stages of capitula for gametophyte and seed analysis are as described previously (Koltunow et al., 1998). Reproductive pathways of sexual and apomictic seeds were determined by ploidy analysis using flow cytometry of single seeds as described by Matzk et al. (2000). Plant transformation was performed as described by Bicknell and Borst (1994), and selected primary transgenic plants were vegetatively propagated for analysis. Seed initiation and viability were determined by examining the number of BF in typically three to five capitula and then counting the number of germinating seedlings on agar plates 15 d after plating on the media (Koltunow et al., 1998). Results were expressed as BF/capitulum and viability/capitulum. DNA and total RNA were isolated from tissues as described by Tucker et al. (2001).

Cytology

To clear ovules, tissue was fixed and treated to remove oxalate crystals as described by Koltunow et al. (1998), dehydrated to 100% ethanol, cleared in methylsalicylate (Tucker et al., 2003), and observed by Nomarski differential interference contrast under a Zeiss Axioskop microscope. Images were captured with a Spot II camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Tissue was fixed and embedded in Spurr's resin, sectioned to 2 μm, and stained in 0.1% toluidine blue in 0.02% sodium carbonate (Koltunow et al., 1998). In situ hybridization was performed as described by Okada et al. (2007).

FIE, MSI1, and RBR cDNA Isolation

Hieracium FIE, MSI1, and RBR were isolated using degenerate PCR oligonucleotides to amplify related sequences from cDNA made from ovaries collected from flowers in stage 6-10 capitula from apomictic and sexual Hieracium plants (Tucker et al., 2003). Full-length sequences were obtained by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (Invitrogen) followed by sequencing. Degenerate primers used to amplify FIE were FIEF433, 5′-GATGARGATAAGG-3′; FIER, 5′-656-CATYCCACARICKAAC-3′; FIEF459, 5′-ACACDSTRAGTTGGGC-3′; and FIER636, 5′-GATTSATYYTTGTTDGCAG-3′. MSI primers were MSI1F1, 5′-TGGAATAATAAYACTCCTTTYYTCTAYGA-3′; MSI1R1, 5′- GCNYTNGARTGGCCNTCNYTNAC-3′; MSI1F2, 5′- TADATRTTYTCNGCCATYTGCCA-3′; and MSI1R2, 5′-TCNGGNGGNCCRTCYTCNGCRTC-3′. The RBR primers were RBRF1, 5′-TTYTTYAARGARYTNCCNCARTT-3′; RBRR1, 5′-AGYTCRTTNGANGGGCTCTG-3′; RBRF2, 5′-GGNYTAGTNTCNRTHTTHHC-3′; and RBRR2, 5′-CKNARNGGAGANACRTANAC-3′.

RNAi Constructs for Downregulation of Hieracium FIE and RT-PCR Analysis

To generate 35S:hpHFIE, a 442-bp fragment of the FIEapo cDNA, spanning amino acids 140 to 288 in the FIE protein sequence, was amplified for cloning in sense and antisense orientation in pHANNIBAL (35S:pN6; Wesley et al., 2001). To generate AtMEA:hpHFIE, the 35S promoter was removed from 35S:hpHFIE using SacI and EcoRI, and the Arabidopsis thaliana MEA promoter fragment (Luo et al., 2000; Tucker et al., 2003) was inserted in its place. Both RNAi constructs were cloned into pBINPLUS and mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 for plant transformation. Hieracium FIE expression was analyzed in total RNA from various tissues by RT-PCR using 25 cycles of 94°C 30s, 55°C 30s, 72°C 30s, and β-tubulin as a reference (Tucker et al., 2003) or from total RNA extracted from ovules dissected from staged capitula using a SyberGreen mix (Thermo Scientific), Rotor Gene 3000 real time PCR machine (Corbett Research), and ubiquitin as an expression control. Primer sequences for Hieracium FIE were RTHFIEF3, 5′-CCGTGTCATTGATGCTGGCAAT-3′; and RTHFIER2, 5′-GCAGCTGCATTGTAGTGGAAATCA-3′; and for ubiquitin were ubQF, 5′-ACTCCACTTGGTCTTGCGTCT-3′; and ubQR, 5′AGTACGGCCGTCTTCAAGC-3′. Hieracium FIE levels in transgenic plants were compared with those in untransformed control plants where the levels were set at 100%. A minimum of three biological replicates was used to generate relative expression data.

Complementation Analysis

Arabidopsis plants were grown in 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiods under fluorescent lighting. The Ler fie mutant provided by A. Chaudhury (CSIRO) contains the same mutation as the fie-2 allele described by Ohad et al. (1999). A cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence PCR marker was used to identify heterozygous fie-2/+ plants that have lost a HinfI site caused by an A-to-G mutation at the border of intron 3. A complementation construct containing 2004 bp of the Arabidopsis MEA promoter (directly upstream from the ATG) fused to 1308 bp of Hieracium FIEapo cDNA (1110 bp of coding sequence and 194 bp of the 3′ untranslated region) was made in the pBINplus vector (van Engelen et al., 1995). Following mobilization to Agrobacterium strain LBA4404 and transformation of At Col-4 plants, four lines were obtained, and lines #1 and #2 were used in subsequent experiments. Heterozygous FIE/fie-2 (Ler) plants were crossed as males with Col-4 wild-type plants and AtMEA:HFIEapo Col-4 lines #1 and #2. Plants containing both the fie-2 mutation and the AtMEA:HFIEapo construct were selected on kanamycin and screened by cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence PCR analysis using standard PCR conditions and the primers fie-2Fwd (5′-TGTTCTATGTATCCTAGCAAATGCTTC-3′) and fie-2Rev (5′-TCCTTATTCAATTAAAACGTAACAGC-3′) followed by HinfI digestion. Flowers from F2 plants were emasculated by removing the sepals, petals, and anthers prior to anthesis. Siliques were collected 3 d postemasculation, fixed in formalin–acetic acid–alcohol stained using hemotoxylin, and scored for the presence of multinucleate central cells (Ohad et al., 1996).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assays

The Clontech yeast two-hybrid system was used. Full-length FIE cDNA was cloned in frame with the lexA DNA binding domain to create a fusion protein. RBR, MSI1, MEA, and CLF cDNA sequences from Arabidopsis were cloned in frame into the pB42AD vector to create fusion proteins with the activator domain. Constructs were tested for autoactivation as described by the manufacturer (Clontech). LexA fusion constructs were transformed into yeast strain EGY048 and selected with SD media without uracil and His. Positive yeast colonies were transformed with constructs containing the activator domain fusion proteins and selected in SD media without uracil, His, and Trp. Positive clones were then plated on SD media (gal/raf) without uracil, His, Trp, and Leu. Growth in selection media indicated positive interaction. Colonies were also plated onto X-gal assay plates (SD gal/raf media without uracil, His, and Trp) where interaction was indicated by the production of blue color. Both the LEU marker gene and β-d-galactosidase gene were under the control of the LexA operator. Cultures were grown on plates at 29°C for 4 to 5 d prior to scoring.

Protein Detection in Yeast

Yeast protein extracts were prepared from log-phase yeast cultures transformed with the appropriate vectors and grown under selection in SD media without uracil and His. Cells were harvested and resuspended in Y-PER (Pierce) with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After one freeze-thaw cycle (1 min in liquid N2 and 1 min at 37°C), extracts were centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000g. Supernatants were denatured in 2× loading buffer and separated in a 4 to 20% acrylamide gel (NuSep). Wet transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (NuSep). The dilutions of primary mouse anti-LexA antibody (Dual Systems) and secondary antimouse IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase were 1:2500 and 1:5000, respectively. The NBT-BCIP liquid substrate system (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect protein bands.

Molecular Modeling of FIE Proteins from Arabidopsis and Hieracium

Three-dimensional (3D) molecular models of Arabidopsis (At FIE) and Hieracium FIE proteins were constructed using the Modeler 9v1 program (Sali and Blundell, 1993; Sanchez and Sali, 1998). To identify the most suitable template for the Arabidopsis and Hieracium FIE proteins, searches were performed through the Structure Prediction Meta-Server (Ginalski et al., 2003), MetaPP server (Rost et al., 2004), SeqAlert (Bioinformatics and Biological Computing, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel), Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al., 2000), and 3D-PSSM Server (Kelley et al., 2000). The best 3D template for modeling the At FIE and Hieracium FIE sequences, based on amino acid sequence identity, was found to be human β-trcp1-skp1-β-catenin complex (chain A), accession number lp22:A retrieved from the PDB (Berman et al., 2000) and called hereafter 1p22:A. BioManager version 2.0 (http://www.angis.org.au/) at the Australian National Genomic Information Service (ANGIS) was used to align 1p22:A with target sequences At FIE and FIEapo. The secondary structure predictions of FIE proteins from Arabidopsis and Hieracium were performed with SAM T06 (Karplus et al., 1998) and with the 3D-PSSM Server (Kelley et al., 2000). The positions of secondary structure elements and hydrophobic clusters were manually examined with hydrophobic cluster analysis software (Callebaut et al., 1997). The positional sequence identity and similarity scores were calculated by the Bestfit program from the ANGIS BioManager version 2.0 (http://www.angis.org.au/) with the implemented gap penalty function and dynamic programming algorithm (Smith and Waterman, 1981). Only 293 amino acid residues of 1p22:A out of the total 435 amino acid residues were relevant for modeling, and these covered ∼90% of the Hieracium FIE and At FIE protein sequences. Structurally aligned 1p22:A and Arabidopsis or Hieracium FIE sequences were used as input parameters to build 3D models on a Linux Red Hat workstation, running a Fedora Linux Core 4 operating system. The final 3D molecular models of Arabidopsis and Hieracium FIE proteins were selected from 40 models that showed the lowest value of the Modeler objective function. The stereochemical quality and overall G-factors of the Arabidopsis or Hieracium FIE models were calculated with PROCHECK (Ramachandran et al., 1963; Laskowski et al., 1993). Z-score values for combined energy profiles were evaluated by Prosa2003 (Sippl, 1993); the plots were smoothed using a window size of 50 amino acid residues. Spatial superpositions of 1p22:A and At FIE structures and 1p22:A and FIEapo structures were performed in the DeepView molecular browser (Guex and Peitsch, 1997) using a fragment alternate fit routine; the root mean square deviation values were 0.76 and 0.64 Å for 286 and 283 amino acid residues, superposed in the Cα carbon positions, for 1p22:A/At FIE or 1p22:A/FIEapo structure combinations, respectively. The electrostatic potentials of the two models were calculated with the Poisson-Boltzmann equation using GRASPv1.3.6 (Nicolls et al., 1991) and mapped onto the molecular surfaces generated with a probe radius of 1.4 Å. The molecular graphics were generated with the PyMol (http://www.pymol.org) and GRASP (Nicolls et al., 1991) software packages.

Accession Numbers

The sequences isolated and described here have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: Hieracium FIEapo, EU439051; Hieracium FIEsex, EU439048; Hieracium MSI1apo, EU439050; Hieracium MSI1sex, EU439047; Hieracium RBRapo, EU439049; and Hieracium RBRsex, EU439053. Other sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: FIE, AAD23584; MSI1, NP200631; RBR, NP200631; CLF, P93831; MEA, NP_563658; Zea mays FIE1, AAT39462; Z. mays FIE2, AAT39467; Z. mays RBR3, AAZ99092; Oryza sativa MSI1, ABF97823.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Analysis of Hieracium FIE Genes.

Supplemental Figure 2. Endosperm Development in Sexual and Apomictic Hieracium.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Hieracium FIE Genomic Sequences Used to Generate the Alignments Presented in Supplemental Figure 1C.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Fritz Matzk for flow cytometry of single seeds analysis and Takashi Okada for critical and thoughtful comments on this manuscript. The research was funded by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, an Adelaide University Premier Scholarship to M.R.T., and a grant from CAPES Brazil to J.C.M.R.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Anna M.G. Koltunow (anna.koltunow@csiro.au).

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Berger, F., Grini, P.E., and Schnittger, A. (2006). Endosperm: An integrator of seed growth and development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9 664–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, H., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, N., Weissig, H., Shindylaov, I., and Bourne, P. (2000). The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell, R.A., and Borst, N.K. (1994). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Hieracium aurantiacum. Int. J. Plant Sci. 155 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell, R.A., and Koltunow, A.M. (2004). Understanding apomixis: Recent advances and remaining conundrums. Plant Cell 16 S228–S245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut, I., Labesse, G., Durand, P., Poupon, A., Canard, L., Chomilier, J., Henrissat, B., and Mornon, J.P. (1997). Deciphering protein sequence information through hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA): Current status and perspectives. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53 621–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanach, A.S., Erasmuson, S.K., Podivinsky, E., Jordan, B.R., and Bicknell, R. (2006). Deletion mapping of genetic regions associated with apomixis in Hieracium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 133 18650–18655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury, A.M., Koltunow, A., Payne, T., Luo, M., Tucker, M.R., Dennis, E.S., and Peacock, W.J. (2001). Control of early seed development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17 677–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya, O.N., Hermon, P., Hantke, S., Muszynski, M.G., Kollipara, K., and Ananiev, E.V. (2003). Duplicated fie genes in maize: Expression pattern and imprinting suggest distinct functions. Plant Cell 15 425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginalski, K., Elofsson, A., Fischer, D., and Rychlewsli, L. (2003). 3D-Jury: A simple approach to improve protein structure predictions. Bioinformatics 19 1015–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, J., Puangsomlee, P., Martin, M., Long, D., Meyerowitz, E.M., and Coupland, G. (1997). A polycomb-group gene regulates homeotic gene expression in Arabidopsis. Nature 386 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossniklaus, U., Vielle-Calzada, J.-P., Hoeppner, M.A., and Gagliano, W.B. (1998). Maternal control of embryogenesis by MEDEA, a Polycomb-group gene in Arabidopsis. Science 280 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. (1997). SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton, A.E., and Berger, F. (2005). Loss of function of MULTICOPY SUPPRESSOR of IRA1 produces nonviable parthenogenetic embryos in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 15 750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haun, W., Laoueillé-Duprat, S., O'Connell, M., Spillane, C., Grossniklaus, U., Phillips, A., Kaeppler, S., and Springer, N. (2007). Genomic imprinting, methylation and molecular evolution of maize Enhancer of zeste (Mez) homologs. Plant J. 49 325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingouff, M., Jullien, P., and Berger, F. (2006). The female gametophyte and the endosperm control cell proliferation and differentiation of the seed coat in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18 3491–3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus, K., Barrett, C., and Hughey, R. (1998). Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics 14 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, A., Oliva, M., Mosquna, A., Hakim, O., and Ohad, N. (2004). FIE and CURLY LEAF polycomb proteins interact in the regulation of homeobox gene expression during sporophyte development. Plant J. 37 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, L., MacCallum, R., and Sternberg, M.J. (2000). Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J. Mol. Biol. 299 499–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T., Harada, J.J., Goldberg, R.B., and Fischer, R.L. (2001). Polycomb repression of flowering during early plant development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 14156–14161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, C., Hennig, L., Bouveret, R., Gheyselinck, J., Grossniklaus, U., and Gruissem, W. (2003). Arabidopsis MSI1 is a component of the MEA/FIE Polycomb group complex and required for seed development. EMBO J. 22 4804–4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltunow, A., and Grossniklaus, U. (2003). Apomixis: A developmental perspective. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 547–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltunow, A.M., Johnson, S.D., and Bicknell, R.A. (1998). Sexual and apomictic development in Hieracium. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Koltunow, A.M., Johnson, S.D., Lynch, M., Yoshihara, T., and Costantino, P. (2001). Expression of rolB in apomictic Hieracium piloselloides Vill. causes ectopic meristems in planta and changes in ovule formation, where apomixis initiates at higher frequency. Planta 214 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, R., MacArthur, M., Moss, D., and Thornton, J. (1993). PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 26 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D., and Roberts, R. (2001). WD-repeat proteins: Structure characteristics, biological function, and their involvement in human diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58 2085–2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, M., Bilodeau, P., Dennis, E.S., Peacock, W.J., and Chaudhury, A. (2000). Expression and parent-of-origin effects for FIS2, MEA, and FIE in the endosperm and embryo of developing Arabidopsis seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 10637–10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarevich, G., Leroy, O., Akinci, U., Schubert, D., Clarenz, O., Goodrich, J., Grossniklaus, U., and Köhler, C. (2006). Different Polycomb group complexes regulate common target genes in Arabidopsis. EMBO Rep. 7 947–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzk, F., Meister, A., and Schubert, I. (2000). An efficient screen for reproductive pathways using mature seeds of monocots and dicots. Plant J. 21 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J., Li, R., Morgan, K., and Simon, J. (1997). Evolutionary conservation and predicted structure of the Drosophila extra sex combs repressor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 6663–6672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolls, A., Sharp, K., and Hönig, B. (1991). Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins 4 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack, M., Grini, P., Jakoby, M., Lafos, M., Koncz, C., and Schnittger, A. (2006). A positive signal from the fertilization of the egg cell sets off endosperm proliferation in angiosperm embryogenesis. Nat. Genet. 38 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack, M., Shirzadi, R., Dissmeyer, N., Dolf, A., Endl, E., Grini, P., and Schnittger, A. (2007). Bypassing genomic imprinting allows seed development. Nature 447 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohad, N., Margossian, L., Hsu, Y.C., Williams, C., Repetti, P., and Fischer, R.L. (1996). A mutation that allows endosperm development without fertilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 5319–5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohad, N., Yadegari, R., Margossian, L., Hannon, M., Michaeli, D., Harada, J.J., Goldberg, R.B., and Fischer, R.L. (1999). Mutations in FIE, a WD polycomb group gene, allow endosperm development without fertilization. Plant Cell 11 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada, T., Catanach, A.S., Johnson, S.D., Bicknell, R.A., and Koltunow, A.M. (2007). An Hieracium mutant, loss of apomeiosis1 (loa1) is defective in the initiation of apomixis. Sex. Plant Reprod. 20 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, O.A. (2004). Nuclear endosperm development in cereals and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 16 (suppl.): S214–S227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, G., Ramakrishnan, C., and Sasisekharan, V. (1963). Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J. Mol. Biol. 7 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, J.C., and Grossniklaus, U. (2003). Diverse functions of Polycomb group proteins in plant development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost, B., Yachdav, G., and Liu, J. (2004). The PredictProtein Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 W321–W326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali, A., and Blundell, T. (1993). Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234 779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, R., and Sali, A. (1998). Large-scale protein structure modeling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 13597–13602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl, M. (1993). Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins 17 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T., and Waterman, M. (1981). Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 147 195–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, M.B., Chaudhury, A.M., Robert, H., Bancharel, E., and Berger, F. (2001). Polycomb group genes control pattern formation in plant seed. Curr. Biol. 11 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, C., MacDougall, C., Stock, C., Kohler, C., Vielle-Calzada, J.P., Nunes, S.M., Grossniklaus, U., and Goodrich, J. (2000). Interaction of the Arabidopsis Polycomb group proteins FIE and MEA mediates their common phenotypes. Curr. Biol. 10 1535–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, C., Schmid, K., Laoueillé-Duprat, S., Pien, S., Escobar-Restrepo, J., Baroux, C., Gagliardini, V., Page, D., Wolfe, K., and Grossniklaus, U. (2007). Positive Darwinian selection at the imprinted MEDEA locus in plants. Nature 448 349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M.R., Araujo, A.C., Paech, N.A., Hecht, V., Schmidt, E.D., Rossell, J.B., De Vries, S.C., and Koltunow, A.M. (2003). Sexual and apomictic reproduction in Hieracium subgenus Pilosella are closely interrelated developmental pathways. Plant Cell 15 1524–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M.R., Paech, N.A., Willemse, M.T.M., and Koltunow, A.M.G. (2001). Dynamics of callose deposition and β-1,3-glucanase expression during reproductive events in sexual and apomictic Hieracium. Planta 212 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Engelen, F.A., Molthoff, J.W., Conner, A.J., Nap, J.-P., Pereira, A., and Stiekema, W.J. (1995). pBINPLUS: An improved plant transformation vector based on BIN19. Transgenic Res. 4 288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkenoog, R., Spielman, M., Adams, S., Fischer, R.L., Dickinson, H.G., and Scott, R.J. (2000). Hypomethylation promotes autonomous endosperm development and rescues post-fertilization lethality in fie mutants. Plant Cell 12 2271–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]