Abstract

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a very rare cause of acute coronary syndromes in young otherwise healthy patients with a striking predilection for the female gender. The pathological mechanism has not been fully clarified yet. However, several diseases and conditions have been associated with SCAD, such as atherosclerosis, connective tissue disorders and the peripartum episode. In this paper we present a review of the literature, discussing the possible mechanisms for SCAD, therapeutic options and prognosis. The review is illustrated with two SCAD patients who had a recurrence of a spontaneous dissection in another artery within a few days after the initial event. Because of the susceptibility to recurrent spontaneous dissections we propose at least one week of observation in hospital. Further, we will elaborate on the possible conservative and invasive treatment strategies in the acute phase of SCAD. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention remains the reperfusion strategy of choice; however, in small and medium-sized arteries with normalised flow conservative treatment is defendable. In addition, after the acute phase evaluation of possible underlying diseases is necessary, because it affects further treatment. (Neth Heart J 2008;16:344-9.)

Keywords: recurrence, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, connective tissue disorder, peripartum episode, atherosclerosis

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a very rare cause of acute coronary syndromes in young otherwise healthy patients with a striking predilection for the female gender. It was reported for the first time in 1931 at the autopsy of a 42-year-old woman.1 Since this first report there have been about 160 case reports, the majority of which were diagnosed postmortem. The clinical presentation of SCAD depends on the extent and severity of the dissection, and ranges from unstable angina to sudden cardiac death. Although the pathological mechanism is not fully clarified, several diseases and conditions have been associated with SCAD. This implicates that SCAD is a heterogeneous disorder in which more than one therapeutic regimen should be considered. In this paper, we present two cases of young women who presented with an acute coronary syndrome due to SCAD. Of interest, both patients had a recurrence of a spontaneous dissection in another artery within a few days after the initial event. We will present a review of the literature and elaborate on the pathogenesis, therapeutic options and prognosis.

Case1

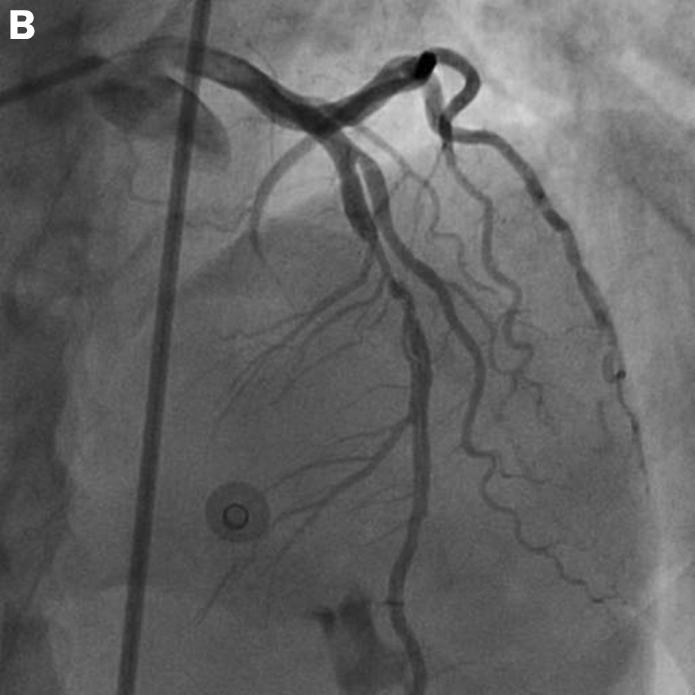

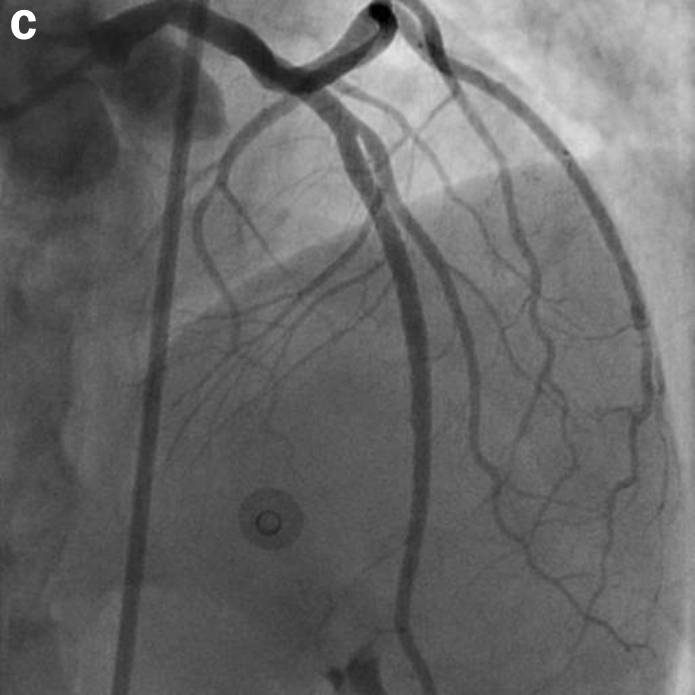

A 36-year-old otherwise healthy female patient was referred to our hospital with an acute inferolateral myocardial infarction in May 2006. Coronary angiog-raphy revealed an occlusive dissection of the distal segment of an obtuse marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery (RCX). The vessel was opened by balloon angioplasty. The other coronary arteries appeared normal on angiography. She was transferred to the referring hospital and treated with LMWHs, aspirin and clopidogrel. Six days later she developed an acute anterior wall infarction and was readmitted. At angiography the obtuse marginal branch was still open. However, there was an occlusion of the mid-LAD. After wire passage, a long spontaneous dissection could be visualised which was treated with drug-eluting stents (figure 1). The infarction was limited and the residual LV function good. Further analysis did not reveal an underlying connective tissue disorder or other systemic disease. Of note, she had delivered a baby four months before her first admission. She was discharged on aspirin, clopidogrel, diltiazem and a statin. After 17 months of follow-up there has been no recurrent myocardial infarction, angina pectoris or heart failure.

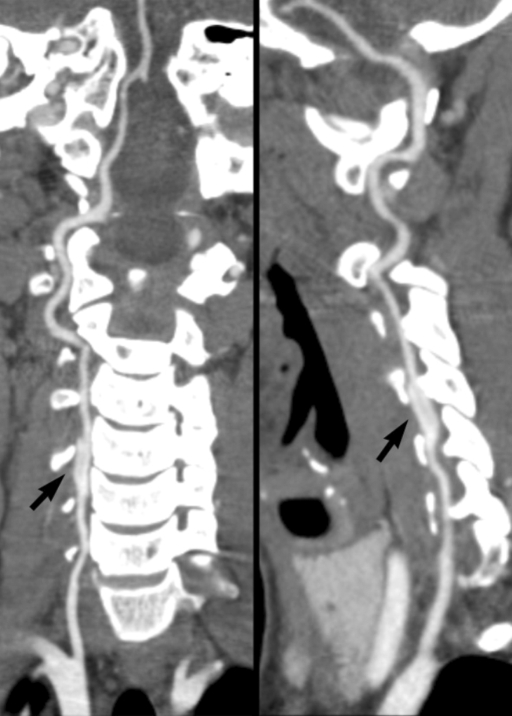

Figure 1.

Panel A shows the left coronary artery (LCA) at first admission with a lateral infarction (dissection MO1). The left anterior descending artery (LAD) has a normal appearance. Six days later the patient developed a dissection of the LAD (panel B), which was treated by stent implantation (panel C).

Case 2

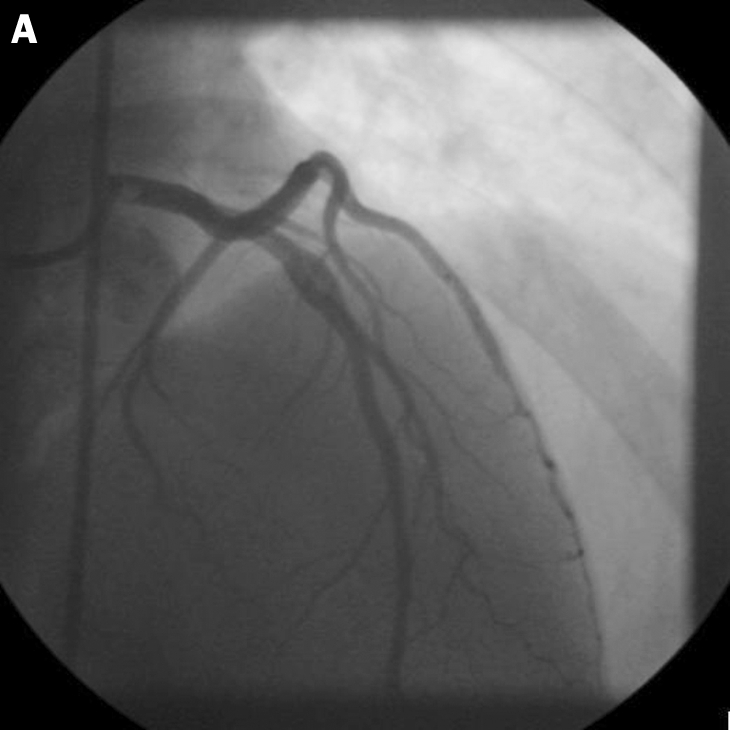

A 42-year-old female patient with a history of mild hypertension was admitted with an acute coronary syndrome in September 2006. Coronary angiography revealed mild atherosclerosis in the right coronary artery (RCA), a normal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and a limited dissection in the distal part of the first obtuse marginal branch. Since there was TIMI 3 flow and the vessel calibre was small, the lesion was treated conservatively. She was admitted to the CCU and put on a regimen of aspirin, clopidogrel and a statin. In addition, hypertension was treated aggressively with an ACE inhibitor, AT2 antagonist and a β-blocking agent. After three days she developed pain in her neck with dizziness. CT scan showed a dissection of the right vertebral artery (figure 2). Medication was continued and the patient recovered slowly with minor residual disturbances in coordination and balance. No secondary cause of hypertension was found. Because of a family history of hypermobility syndrome and some typical facial characteristics, Ehlers-Danlos type IV was suspected, but this disease was ruled out a few months later. Further recovery was uneventful and after 13 months of follow-up there have been no recurrent myocardial infarctions, angina pectoris or heart failure.

Figure 2.

Panel A shows an AP view of the vertebral artery. Panel B shows a lateral view of the vertebral artery. The arrows are pointing at the dissection line.

Discussion

SCAD is a very rare condition with an incidence of 0.1% for patients who are referred for coronary angiography.2 Since SCAD may lead to death in the preclinical phase and dissections of the coronary arteries are often difficult to recognise, many authors believe the incidence is underestimated.3 The mean age at presentation is 35 to 40 years and more than 70% of SCAD cases are women.4 Classically, the patients are divided into three groups: a peripartum, atherosclerotic and idiopathic group.4 This classification, however, does not cover all possible underlying conditions resulting in SCAD. Therefore, we have added an extra group for patients with an underlying condition other than pregnancy and atherosclerosis.

Peripartum episode

One third of all SCAD cases occur in the peripartum period,4,5 of which one third in late pregnancy and two thirds in the early puerperal period. The peak incidence is in the second week after delivery.6 The earliest reported case occurred within nine weeks of conception and the last three months postpartum. Only 30% of the patients in this group had known risk factors for coronary artery disease.6 The role of the peripartum period in the pathogenesis is still unclear. Changes in the levels of sex hormones are considered to play an important role. Especially high levels of oestrogens are thought to change the normal arterial wall architecture, resulting in susceptibility to spontaneous dissections. These changes include hypertrophia of the smooth muscle cells, loosening of the intercellular matrix due to an increase in acid mucopolysaccharides and decreased collagen production in the media.7-9 On top of these changes, elevated cardiac output, increased total blood volume and straining and shearing forces during labour may result in increased wall stress. Thus, both hormonal and haemodynamic changes in pregnancy are thought to predispose to intimal tears in the arterial wall and coronary artery dissections.

Atherosclerosis

There are several conditions other than pregnancy that have been associated with SCAD. In about 30% of SCAD patients an underlying cause other than pregnancy can be identified, most frequently an atherosclerotic plaque rupture.4 Several lines of evidence suggest that mild atherosclerosis is even more often the underlying cause than assumed previously.10-12 Celik et al. even reported that all their non-pregnant patients had a certain degree of atherosclerosis, as in our second case.13 With the help of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) studies, Hering et al. demonstrated that in 35 of 42 SCAD patients, underlying atherosclerotic disease was detectable.12 The pathophysiological mechanism appears to differ from the spontaneous dissection in pregnancy. An increased density of vasovasorum due to atherosclerotic plaque formation may cause bleeding and even rupture, which can lead to dissection of adventitia from media and may result in a rupture of the intima.14

Other causes and conditions

In the minority of cases, SCAD can be associated with connective tissue diseases such as Marfan's syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos type IV. In these connective tissue disorders a medial degeneration of the coronary arteries is thought to lead to weakness of the arterial wall and increased susceptibility to spontaneous dissections.15,16 An association between SCAD and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has also been reported.17,18 In this disease a general vasculitis is considered to be the pathological mechanism leading to chronic inflammation of the vessels and susceptibility to spontaneous dissections. In several other case reports an association is described between SCAD and a certain condition such as vigorous exercise,19 prolonged sneezing20 or cocaine abuse, in which coronary spasms are thought to cause dissections.21 Some authors also posed a relation with the use of oral contraceptives and the menstrual cycle.22

Idiopathic

In the majority of cases, an underlying condition which may lead to SCAD cannot be identified at all and is subsequently classified as idiopathic. Although there is a weak association with smoking and hypertension,23 the affected individuals do not usually have conventional risk factors for atherosclerosis at all and are young and healthy otherwise, mostly of the female gender.

Clinical features

SCAD is thought to be the consequence of an intramural haematoma of a coronary artery, resulting in a false lumen which compresses the true lumen, with subsequent myocardial ischaemia.3 The clinical presentation of SCAD depends on the extent and severity of the dissection, and ranges from unstable angina to sudden cardiac death. The pathological mechanism leading to this dissection depends on the underlying disease, if present. Patients with SCAD can present with a broad spectrum of symptoms from an acute coronary syndrome to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, heart failure or even sudden cardiac death. When a young woman without any risk factors presents to the hospital with one of these previously mentioned clinical features, the clinician should have a high grade of suspicion for SCAD and emergency angiography should be considered. Dissection of the left anterior descending artery is the most common location in women, whereas right coronary artery dissection is most common in men.3,4 Recognition of the dissection can be quite difficult and may require multiple angio-graphic views or IVUS to confirm the diagnosis.10,11,24 In case 1 we decided not to perform IVUS because on angiography the dissection line in the LAD was clearly visible and there was no doubt about the diagnosis. In case 2 an IVUS was not performed because the distal MO 1 branch was too small.

Treatment and diagnostic work-up

There is no specific guideline to treat a spontaneous coronary artery dissection. In case of presentation with an acute myocardial infarction with ongoing ischaemia, the first objective should be to restore normal coronary flow. Fibrin-specific thrombolytic drug therapy is discouraged because it may result in further propagation of the dissection due to progression of the intramural haematoma.25 Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains the reperfusion strategy of choice. If the vessel is open and the flow normalised at the time of angiography, it is defendable to treat the dissection conservatively. Good angiographic and clinical outcomes have been described with medical treatment only.2,26 With conservative measures, coronary artery dissections have even shown complete angiographic resolution after a year.2,19,20 Although many interventionalists feel uncomfortable with conservative medical treatment only, this approach still seems wise in small and medium-sized vessels with normal flow. However, when it is a large epicardial vessel, placement of a stent will often be the treatment of choice. In case of multivessel or left main involvement, several case reports also describe treatment with urgent surgical revascularisation.24 At the first presentation of case 1 with an inferolateral myocardial infarction, a distal MO1 branch was recanalised only with balloon angio-plasty, because of small vessel size. At her second presentation with an anterior wall myocardial infarction three days later, a long dissection in the LAD with TIMI0 flow was encountered. This vessel was treated with three long drug-eluting stents with an excellent result. In our second case there was already TIMI 3 flow in the dissected MO1 branch and therefore angioplasty was not performed. We decided to treat her medically, which still seems to be successful. Treatment with heparin/low-molecular-weight heparin is advised in the first days after the dissection.2,26 Furthermore, ACE inhibitors or AT2 antagonists are of particular interest, because the renin-angiotensin system has been shown to be involved in the regulation of matrix metallo-proteinases (MMPs). These MMPs can stimulate the degradation of collagen and elastin and impede the structure and integrity of the vessel wall. ACE inhibitors and AT2 antagonists may inhibit the expression of MMPs and stabilise the vessel wall.

The phase after the event should not only be used for the patient to recover from the infarction, but also to evaluate the possible cause of SCAD, because it affects the choice of therapy. Treatment should be tailored to the individual. Coronary angiography as well as IVUS will help to identify signs of coronary atherosclerosis. In case of atherosclerosis, aggressive measures should be taken to stabilise atherosclerotic plaques. These measures include aggressive lipid lowering by statins, β-blockade, antihypertensive therapy and antiplatelet therapy. However, when there are no signs of atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries, statins are not indicated, although β-blockers and platelet inhibitors do need to be continued after discharge. Whether to use aspirin or clopidogrel or both in conservatively treated patients remains debatable.2

Pregnancy testing should always be performed in premenopausal women. If an SCAD patient is indeed pregnant, statins and ACE inhibitors should not be given due to their teratogenic effects. A connective tissue disease should be suspected from a positive family history or abnormalities on physical examination. There is assumed to be an association between SCAD and two connective tissue disorders, namely Marfan's syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos type IV. Marfan's syndrome is an autosomal dominant inheritable disorder caused by a mutation in the FBN1 gene. However, 25% of Marfan cases do not inherit the FBN1 gene, but are due to new mutations. Although it has a variable pheno-typic expression, it may present with symptoms of the skeletal, cardiovascular and ocular system. Skeletal manifestations are a reduced upper to lower body segment ratio, arm span exceeding height and arachno-dactyly with hyperlaxity of the joints. Cardiovascular symptoms are aortic insufficiency, aortic aneurysms, mitral valve prolapse and insufficiency. Manifestations of the ocular system are ectopia lentis. If the diagnosis is suspected, genetic testing for a mutation in the FBN1 gene can be performed.27

The other connective tissue disorder is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. This syndrome combines a group of six forms of disorders that share hyperelasticity, fragility of the skin and hypermobility of the joints. Ehlers-Danlos type IV, also called the vascular type, is an autosomal dominant disorder characterised by spontaneous rupture of large and medium-sized arteries. In contrast to the other groups of Ehlers-Danlos, joints in the type IV group are only mildly hypermobile. However, there are some very characteristic facial features, including a thin delicate pinched nose, thin lips, hollow cheeks and prominent staring eyes because of absence of adipose tissue in this region. In addition, there is a thin translucent and easily bruising skin that is usually mildly elastic. If the diagnosis of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV is suspected, it can be confirmed by performing genetic testing and skin biopsies to analyse collagen obtained from cultured fibroblasts.28

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may also lead to spontaneous dissections due to two possible mechanisms: atherosclerosis and vasculitis. SLE is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause which can effect almost every organ. It should be suspected when there are non-specific symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, or anaemia. A complete blood count and differential, inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) should be measured. If these parameters are normal, a vasculitis caused by a chronic inflammatory disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus is unlikely.29 Thus, referral and further work-up, such as imaging, skin biopsies and genetic testing, is only indicated when there are typical findings for a connective tissue or systemic disorder.

Neither of our patients were pregnant at the time of presentation and they were not less than three months postpartum. Case 1 was four months post-partum. Because haemodynamic stress is no longer encountered four months after delivery and arterial wall changes have returned to normal,6,7 we doubt that this patient belongs to the peripartum group. In addition, there were no signs of connective tissue disorders, SLE or atherosclerosis. Therefore, we assigned her to the idiopathic group.

In our second case there was a suspicion on Ehlers-Danlos type IV because of a family history of the hyper-mobility syndrome with some typical facial characteristics. However, genetic and collagen analysis did not reveal Ehlers-Danlos type IV. Because of the presence of mild atherosclerosis on the angiogram and no other underlying conditions, we assigned her to the atherosclerotic group.

Prognosis

The overall mortality in reported cases of the peripartum group is 38%.6 Patients with atherosclerosis as an underlying disease are thought to have a better prognosis due to collateral circulation which may develop due to chronic atherosclerosis.13 Also men tend to have a better chance of survival compared with women, who have an even worse prognosis when they are not in the peri- or postpartum period.3,4 In general, it can be stated that the long-term prognosis of patients with SCAD is favourable if they survive the acute phase.2 Although survival rates and prognosis of patients who present with SCAD vary widely in the literature, data extracted from small series and case reports show survival rates between 70 and 90%.3,4 In a review comprising 152 cases over the last 50 years, Kamineni et al. reported that 50% of patients with SCAD developed a recurrent dissection within two months. We can confirm these findings because both our patients had a recurrent dissection either in a vertebral artery or a coronary artery within one week after the first event. This suggests an enhanced susceptibility to spontaneous dissections in the acute phase. The high chance of developing a recurrent dissection is indicative for a general vessel weakness. This hypothesis is confirmed by the observation that in more than 40% of pregnant SCAD patients, dissections could be demonstrated in more than one vessel.6 So it seems that there is a systemic susceptibility to dissections at a certain point in life, which is marked by the initial event. Therefore we recommend monitoring patients with SCAD for at least one week in the hospital.

Conclusion

SCAD is a rare, multifactorial and complex disease which occurs predominantly in young, otherwise healthy subjects. Its presentation may vary from unstable angina to sudden cardiac death. In the acute phase primary PCI remains the reperfusion strategy of choice; however, in small and medium-sized arteries with normalised TIMI flow conservative treatment is defendable. Further medical therapy should be tailored to the individual, depending on the underlying condition. Patients have a high risk of recurrent dissections in other arteries several weeks after the first event, suggesting a general weakness of the arteries. The prognosis appears to be good, if the patient survives the acute phase. At the moment, a study is ongoing (DISCOVERY: DISsections of the COronary arteries: Veneto and Emilia RegistRY) that will provide more insight into the pathogenesis.

References

- 1.Pretty HC. Dissecting aneurysm of coronary artery in a woman aged 42:rupture. BMJ 1931;1:667 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maeder M, Ammann P, Angehrn W, Rickli H. Idiopathic spontaneous coronary artery dissection: incidence, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Card 2005;101:363-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamineni R, Sadhu S, Alpert JS. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: report of two cases and a 50-year review of the literature. Cardiol Rev 2002;10:279-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Maio SJ Jr, Kinsella SH, Silverman ME. Clinical course and long-term prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol 1989;64:471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coco P, Thiene G, Penelli N. Ematoma aneurisma dissecante spon-taneo delle coronarie e morte improvisa. G Ital Cardiol 1990; 20:795-800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koul AK, Hollander G, Moskovits N, Frankel R, Herrera L, Shani J. Coronary artery dissection during pregnancy and the postpartum period: two cases and review of the literature. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2001;52:88-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asuncion CM, Hyun J. Dissecting intramural hematoma of the coronary artery in pregnancy and the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol 1972;40:202-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heefner WA. Dissecting hematoma of the coronary artery. A possible complication of oral contraceptive therapy. JAMA 1973; 223:550-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnet J, Aumailley M, Thomas D, Grosgogeat Y, Broustet JP, Bricaud H. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: case report 2and evidence for a defect in collagen metabolism. Eur Heart J 1986;7:904-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ichiba N, Shimada K, Hirose M, Kobayashi Y, Hirata K, Sakanoue Y. et al. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Plaque rupture causing spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a patient with acute myo-cardial infarction. Circulation 2000;101:1754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunetti ND, Pellegrino PL, Mavilio G, Cuculo A, Ziccardi L, Correale M, et al. Spontaneous coronary dissection complicating unstable coronary plaque in young women with acute coronary syndrome: case reports. Int J Cardiol 2007 ;115:105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hering D, Piper C, Hohmann C, Schultheiss HP, Horstkotte D. Prospective study of the incidence, pathogenesis and therapy of spontaneous, by coronary angiography diagnosed coronary artery dissection. Z Kardiol 1998;87:961-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celik SK, Sagcan A, Altintig A, Yuksel M, Akin M, Kultursay H. Primary spontaneous coronary artery dissections in atherosclerotic patients. Report of nine cases with review of the pertinent literature. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001 ;20:573-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung S, Mithani V, Watson RM. Healing of spontaneous coronary dissection in the context of glycoprotein IIB/IIIA inhibitor therapy: a case report. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2000;51:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judge DP, Dietz HC. Marfan's syndrome. Lancet 2005;366:1965-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adès LC, Waltham RD, Chiodo AA, Bateman JF. Myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery dissection in an adolescent with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV due to a type III collagen mutation. Br Heart J 1995;74:112-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldoboni AH, Hamza EA, Majdi K, Ngibzadhe M, Palasaidi S, Moayed DA. Spontaneous dissection of coronary artery treated by primary stenting as the first presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Invasive Cardiol 2002;14:694-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma AK, Farb A, Maniar P, Ajani AE, Castagna M, Virmani R, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosis. Hawaii Med J 2003;62:248-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi JW, Davidson CJ. Spontaneous multivessel coronary dissection in a long distance runner successfully treated with oral antiplatelet therapy a case report and review of the literature. J Invasive Cardiol 2002;14:675-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Da Gama MN, Lemos-Neto PA, Ramirez JA, Sposito AC, Horta PE, Perin MA, et al. Spontaneous healing of primary dissection of the coronary artery. J Invasive Cardiol 1999;11:21-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinhauer JR, Caulfield JB, Spontaneous coronary artery dissection associated with cocaine abuse: case report and brief review. Cardiovasc Pathol 2001;10:141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slight R, Behranwala AA, Nzewi O, Sivaprakasam R, Brackenbury E, Mankad P. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a report of two cases occurring during menstruation. N Z Med J 2003;116:U585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhawan R, Singh G, Fesniak H. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: the clinical spectrum. Angiology 2002;53:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auer J, Punzengruber C, Berent R, Weber T, Lamm G, Hartl P, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection involving the left main stem: assessment by intravascular ultrasound. Heart 2004;90:e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buys EM, Suttorp MJ, Morshuis WJ, Plokker HW. Extension of a spontaneous coronary artery dissection due to thrombolytic therapy. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1994;33:157-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarmento-Leite R, Machado PRM, Garcia SL. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: stent or wait for healing. Heart 2003: 89;164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De PaepeA, Devereux RB, Dietz HC, Hennekam RC, Pyeritz RE. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1996;62:417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, Byers PH. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med 2000;342:673-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von Feldt JM. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Recognizing its various presentations. Postgrad Med 1995;97:79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]