Abstract

Aims: The content of novel interventions is often not well specified. We provide a detailed account of the rationale for and redevelopment of an Internet resource for hazardous drinkers—Down Your Drink (DYD) (www.downyourdrink.org.uk). Development Work: An iterative process blended literature reviews of Internet interventions for health conditions and brief treatments for alcohol problems, feedback from users of the original site and from users panels, and completion of a series of developmental tasks. Intervention: The detailed structure and content of the new version of the website is presented. This permits an appreciation of the intended interaction between the user and the intervention, and emphasizes both the freedom of choice available to the user to access diverse material for personal benefit and the value of a clear organizational structure. Conclusions: Presentation of detailed information on the theoretical underpinning, content and structure of an intervention makes it easier to interpret the results of any evaluation and is likely to be of use to those developing other online interventions for alcohol or other health behaviours.

Introduction

It is widely recognized that hazardous drinking in the general population has a considerable impact on public health (Department of Health, 2004). Brief interventions reduce consumption; however, their impact has been limited by poor implementation (Kaner et al., 2007). It is important, therefore, to explore new ways to reach hazardous drinkers who might be able to benefit.

The Internet is being increasingly used to deliver behaviour change interventions to large numbers of people. They are convenient to use, acceptable to users and provide high-quality information and advice (Murray, 2008). There is a developing research literature on the effectiveness of Internet interventions, but it is often difficult to interpret the findings, either because the interventions are not adequately described or because the intervention stops being available once the research has been completed. Furthermore, the lack of adequate descriptions of sites and any theoretical rationale on which they are based make it hard to learn from previous work in the field and build on others’ expertise and experience when developing new interventions.

In recent years a number of Internet interventions have been developed for hazardous drinkers. A recent systematic review concluded that these web-based interventions are readily used, but there is little information about which elements of such programmes may be most useful (Bewick et al., 2008).

The Down Your Drink (DYD) randomized controlled trial (ISRCTN31070347) was designed as a two-arm online randomized controlled trial (Murray et al., 2007). The DYD site hosts a complex intervention made up of a number of components (Medical Research Council, 2000; Campbell et al., 2007). The original version of DYD was an Internet-based 6-week interactive programme based on cognitive behavioural techniques and the stages of change model (Linke et al., 2004). Users were required to log on weekly to read material and complete exercises. In revising the site a number of factors were to be kept in mind.

Firstly, there were strong indications that the original version of the intervention had been well liked and reached its target users. There was also some preliminary, although uncontrolled, evidence that the site might be effective in helping some heavy drinkers to reduce their consumption and alcohol-related harm (Linke et al., 2007). Indeed, this evidence provided the rationale for undertaking a controlled trial.

Secondly, some of the feedback received from users had been critical of elements of the site that prevented open access to the intervention. It was felt, in particular, that time locks were not appropriate for the Internet where the ability to navigate freely through health-related information is the norm. In revising the site the DYD team considered it important to reflect the ethos of the Internet in both functionality and the ‘feel’ of the site. Hence, the time locks were to be removed and the graphics and images extensively revised. This specific user feedback echoed recently published work determining user criteria for Internet interventions, which had specified easy navigation as essential (Kerr et al., 2006).

Thirdly, although there are potential advantages associated with the increasing availability of high-speed broadband and bandwidth, it was important not to disadvantage users with older equipment and keep in mind accessibility, short download times and ease of reading while developing innovations.

Development Work

The redevelopment of the DYD intervention involved an iterative process over a period of 12 months. The elements in this process included (i) literature reviews of (a) the development of Internet interventions for health conditions and (b) developments in brief treatments for alcohol problems; (ii) feedback from users of the original site; (iii) advice and input from alcohol treatment professionals and researchers; (iv) the formation of a multidisciplinary development team and (v) iterative feedback from user panels.

Literature Review

Internet interventions for behaviour change

Although there is growing consensus that Internet interventions can be effective both for health promotion (Wantland et al., 2004; Walters et al., 2006; Norman et al., 2007; Saperstein et al., 2007; Vandelanotte et al., 2007; van den Berg et al., 2007) and for improving self-care in long-term conditions (Nguyen et al., 2004a, 2004b; Kerr et al., 2006); there are relatively few data on how such interventions achieve their effects (Noar et al., 2007). The following features appear to be associated with effectiveness of interventions: an underpinning theoretical approach (Vandelanotte et al., 2007), provision of tailored or personalized information (Noar et al., 2007), and enhancing the user's self-efficacy (Lorig et al., 2006). A noted feature of Internet interventions is the high attrition rate (Eysenbach, 2005; Linke et al., 2007), and it appears as if repeated access to interventions, with on-going support, advice and input, may be more effective than single exposures (Vandelanotte et al., 2007). Interactivity is also associated with effectiveness (Vandelanotte et al., 2007). Computerized cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to be effective in the management of mental health problems (Kaltenthaler et al., 2002; Spek et al., 2007) as well as other conditions such as reducing the distress associated with tinnitus (Spek et al., 2007; Cuijpers et al., 2008).

Users have clear views about what they look for in Internet interventions. A qualitative study of users’ criteria for Internet interventions included strong views on language and tone, visual appearance, ease of navigation, range of interactive components available and demonstration of trustworthiness (Kerr et al., 2006).

Interventions for alcohol misuse

The rationale for basing the intervention on the stages of change model has recently been challenged (West, 2005). It was decided, therefore, to redesign the intervention to be congruent with current brief intervention and treatment principles for alcohol problems but to retain the stages of change model in the narrative as a heuristic device for users. The original DYD site was largely based on self-help material derived from cognitive behavioural psychology (Heather and Robertson, 1987). A specific element of this approach is the development of relapse prevention strategies that aim to reduce the likelihood of any lapses and help manage them effectively should they occur (Marlatt and Gordon, 1985).

Research into the effectiveness of alcohol treatment programmes continues to support CBT (Irvin et al., 1999). CBT has been shown to be as effective as Motivational Enhancement Therapy and Twelve-Step Facilitation (Project MATCH, 1997) and a review of clinical trials for alcohol use problems showed strong evidence for efficacy for a range of behavioural interventions (Miller and Wilbourne, 2002).

There is also good evidence for the effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing (MI) (Hettema et al., 2005, UKATT, 2005, Vasilaki et al., 2006). MI is a non-judgmental, non-confrontational approach that attempts to increase clients’ awareness of the consequences of their drinking (Miller and Rollnick, 1991, 2002). It emphasizes the autonomy of the user in the decision-making process. Self-assessment tools provide raw material for consideration. An important element of the motivational approach is the enabling, non-confrontational and reflective therapeutic attitude adopted by a practitioner. On a website, this can be reflected in the style of writing (tone of voice) in the text and the construction of interactive exercises that encourage reflection and individual choice.

User Feedback

A qualitative review of the written feedback obtained from a sample of 100 completers of the original DYD enabled the identification of key topics and themes that would be helpful in the development of the site. The main areas identified were the importance of supporting motivation for change, increasing self-efficacy and providing support for any changes that occur. Users greatly valued the self-help tools on the site such as the online drinking diary. They were also appreciative of the encouraging and non-judgemental writing style and ‘tone’.

This information was considered at an ‘away day’ by the site developers who had a broad range of expertise including psychology (S.L.), addictions research (J.M.), primary care and alcohol research (P.W.) and health research (Z.K.). The event was also attended by the website programmers, an Internet research consultant, an experienced picture editor and a researcher on Internet interventions for chronic health conditions. In addition, consultations were held with a graphic artist and a film maker with an interest in website development. This ‘away day’ helped to identify the development work required for the updated site.

Once the original site had been modified, user panels reviewed the changes and new features. The panels included a user representative and members of the general public who responded to a request to provide feedback on an Internet intervention for excessive drinking. A mock-up of the revised site (i.e. content without functionality) was shown in a series of focus groups that included a facilitated discussion. A preliminary functioning version was then developed and made available to users for home use. These users were asked to keep diaries of their site use and then discussed their thoughts on the site in a subsequent focus group. In addition an email address was made available and users were invited to submit responses, reactions and comments to one of the researchers (Z.K.).

The Intervention

A website (www.downyourdrink.org.uk) was constructed to host the DYD intervention and other components required for the trial. Following registration and the completion of the trial requirements, visitors were asked to provide their own user name and choose a password.

Welcome Page and Home Page

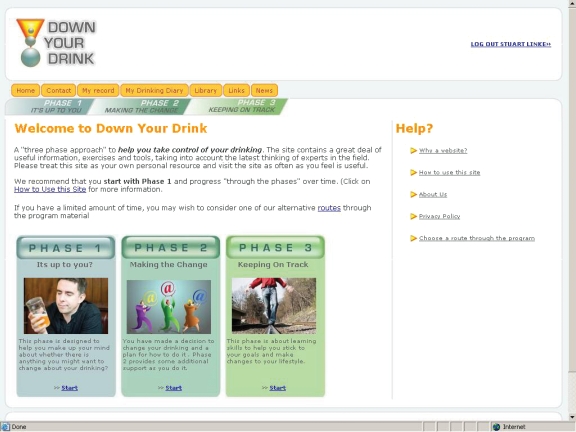

Users entering the intervention site for the first time do so via the home page (see Figure 1). This page also contains links to directions on how to use the programme and information about the creators of the site (about us) and the privacy policy.

Fig. 1.

Down Your Drink home page.

When users log in (using their username and password) on subsequent occasions they come directly to the welcome page and are presented with the options of going back to the last page they were on (bookmark), starting from the beginning of the three-phase programme (home page), choosing a ‘route’ through the programme (see below) or going straight to the ‘drinking diary’.

Phases

The DYD programme is based on brief intervention and psychological treatment principles. The programme offers three phases, each of which is divided into levels with different types of material and associated exercises and tasks. If followed in order they provide a natural progression through three stages: decision making, implementing change and relapse prevention. However, users are free to design their own route through the programme materials as they wish.

Phase 1 (‘It's up to You’)

Phase 1 applies principles based on MI to help people reach high-quality decisions about whether and how to change their drinking. MI places great importance on what people actually say in discussions about change, a feature which cannot be directly replicated in an Internet intervention. The approach, however, contains a number of principles that can be adapted for online use. We developed material that was organized into four levels for users to consider before implementing attempts at behaviour change.

Level 1 invites the user to consider whether this programme is the right one for them. The personal thinking drinking record is introduced (see below) with a few simple examples alongside some educational material about alcohol and alcohol-related problems. This is followed by exercises designed to help identify costs and benefits of current levels of drinking and to articulate personal values. Users are then guided to undertake an initial evaluation of their situation.

Level 2 focuses on assessing current levels of consumption and its effects. There is information on estimating standard units of alcohol, an automated alcohol unit calculator, blood alcohol concentration calculator, guidance on sensible drinking levels and a description of how to record drinking episodes in a drinking diary. This is followed by exercises to enable age- and gender-matched comparison with the general population. Material is also provided on binge drinking.

Level 3 focuses directly on the dilemmas faced when making a decision to alter drinking behaviour and the possible barriers to change. Users are encouraged to think carefully about, and record, their responses to the material and rate the importance of change and their confidence that they can achieve change. Following this exercise, the users are introduced to the role of setting personal targets with guidance about setting targets and planning in advance for resetting the target if there are difficulties.

Level 4 encourages users to take an overview of their situation prior to actually defining the change they wish to make. The programme then provides a description of the ‘stages of change’ model (Prochaska et al., 1992) and guidance on conducting behavioural experiments. The final material in phase 1 requires the user to set out a detailed plan for change, including a start date.

Phase 2 (‘Making the Change’)

Level 1 of phase 2 begins with a plan for support through the first few days of a planned change in drinking. The focus is on conducting a behavioural analysis to identifying factors that might put the plan at risk. There are exercises asking users to identify the people they usually drink with, the places where they commonly drink and the times of a day in which they often consume alcohol. This is followed by educational material about controlled drinking strategies. There are exercises on identifying specific sources of emotional and practical support and how and when to get medical or other professional help if required (for example if suffering from alcohol withdrawal effects). Users are encouraged to set a review date to consider how things went. Users are invited to reward themselves if things have gone to plan and to re-evaluate if not.

The purpose of level 2 is to help the individual identify and develop skills and capacities to enable them to stick to their plans and achieve their goals. A key tool to help with this is the drinking episode diary. The online drinking diary in the original version of DYD was consistently identified in the qualitative feedback as one of the most useful elements helping people to keep track of their consumption and control their drinking. The new drinking episode diary retained the monitoring function, but new elements were added to allow in-depth self-analysis of drinking behaviour (see below). The use of some other e-tools to support change is also discussed in this phase. These include the blood alcohol concentration calculator, the thinking drinking record and a sign-up service of daily emails (drinking tips). The educational material includes sections on assertiveness, self-control and stimulus-control strategies, self-efficacy, cognitive approaches, being determined and self-reinforcement.

Many of the sections of the educational material in this phase (and similarly in phase 3) have a common structure. There is an initial narrative component that gives the user information about the topic, followed by exercises to be completed. For example, in the section on self-efficacy the narrative section focuses on the different ways a sense of self-confidence can be developed. The exercises that follow support this by asking the user to name some achievable targets for themselves (which are recorded in ‘my record’—see below) and also to identify suitable role models.

Phase 3 (‘Keeping on Track’)

This phase is for those who have attempted to change their drinking and want support in maintaining change and avoiding relapse. It is based on the principles of relapse prevention (Marlatt and Gordon, 1985). A number of concepts are introduced at this stage including dependence, cravings and lapses. Early in level 1, users have the opportunity to rate the extent to which they currently feel in control of their drinking and to complete the 5-item Severity of Dependence Scale (Gossop et al., 1992). Users are invited to reflect on the progress made. A strong theme is that drinking more than planned on an occasion need not be a relapse and does not mean failure.

Level 2 of this phase builds on material presented in the previous phases. There is a detailed discussion on maintenance of change that serves as the rationale for the introduction of a wide range of topics including high risk situations, cravings, assertiveness, sleep problems, nutrition and relationships.

Drinking Episode Diary

The drinking episode diary enables the user to record how much and what they drink each day. A range of information can be collected including the day and time of drinking, the people they were drinking with, where they were drinking, how many units and calories (and weight watcher points) were consumed and costs, thoughts, feelings and actions associated with drinking. The diary includes a calculator integrated with a report writer that can produce descriptive summaries of these variables during recorded drinking episodes, over varying time periods (see Figure 2). These summaries can be entered manually or calculated automatically by entering the type, brand and size of drink.

Fig. 2.

Drinking episode diary.

A keyword search facility enables users to search through their responses to help identify drinking patterns. This may help to identify risky situations for drinking or times at which they were successfully able to exercise control. If the person has recorded thoughts and feelings associated with drinking, these can be displayed as well. For example, it is possible to search the database to see how much they drank with a particular person, in a particular place, what feelings were associated and what their most frequently consumed beverage was.

My Record

Throughout the three phases individuals are invited to undertake exercises, and this content is recorded in a private space on the website to which only they have access. These exercises are specifically designed to mirror components of face-to-face discussions about changing drinking and to elicit similar content. The record follows the phase and level structure and there are hot links to enable the user to navigate easily back to the main programme.

Contacts

The contacts page enables the user to control communication from the website to their email address. In addition to the usual ability to edit personal details and contact information, there are occasional newsletters about alcohol-related matters, an RSS news feed and daily emails. These daily emails are signed by ‘the DYD team’ and contain educational and informational ‘tips’ (with links back to the appropriate point in the programme). These emails can be turned on or off by the user at any point.

Routes

The DYD site is extensive and the routes facility was provided so that users could be guided to navigate the content in time-restricted situations and to simplify choice of material. These routes each present a selection of pages chosen from each of the phases. There are 1-h, 5-day and 4-week routes presented as options.

Discussion

The redeveloped DYD site differs from other web-based interventions for hazardous drinking in that it may be used either as a brief intervention or as a stand-alone treatment programme involving long term and frequent contact. It remains to be seen whether this is effective and if any particular element of the programme is of more help than others. A detailed analysis of the use of different components of the intervention will be possible as part of the DYD trial.

Internet interventions may be integrated with conventional health promotion information and face-to-face interventions. There may be particular scope for including Internet interventions as an option within a stepped care approach. The content and style of interventions may be adapted to populations that differ by such factors as age, gender, ethnicity, occupation and social class.

The development of multi-faceted Internet interventions is a lengthy and time-consuming task; however, such interventions should not be static and will need to be updated. Future Internet interventions will need to take account of developments in our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the effectiveness of interventions. Similarly, developments in computer science, psychology and the study of e-health interventions will enable a better understanding of how to create programmes that will promote, encourage and sustain change in health-related behaviour.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the National Prevention Research Initiative (grant G0501298), which includes the following funding partners: British Heart Foundation; Cancer Research UK; Department of Health; Diabetes UK; Economic and Social Research Council; Medical Research Council; Research and Development Office for the Northern Ireland Health and Social Services; Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Executive Health Department; and the Welsh Assembly Government (http://www.npri.org.uk). The Alcohol Education and Research Council provided additional funding to assist with developing the intervention site (grant DP06/02). No funder has had any role in the preparation of the manuscript or the decision to submit. We are grateful to Alcohol Concern for their collaboration with the trial. We thank Harvey Linke of Net Impact and Richard McGregor of Codeface Ltd for their work in developing the intervention, comparator and trial websites, Cicely Kerr who contributed the idea of ‘routes’, Jo Burns for project management and Orla Ward for administrative support.

References

- Bewick BM, Trusler K, Barkham M, et al. The effectiveness of web-based interventions designed to decrease alcohol consumption—a systematic review. Prev Med. 2008;47:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. Br Med J. 2007;334:455–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2008;31:169–77. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Cabinet Office, Prime Minister's Strategy Unit Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy for England. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Griffiths P, Powis B, et al. Severity of dependence and route of administration of heroin, cocaine and amphetamines. Brit J Addict. 1992;87:1527–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Robertson I. Let's Drink to Your Health: A Self-Help Guide to Sensible Drinking. Oxford: BPS Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, et al. Efficacy of relapse prevention: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:563–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenthaler E, Shackley P, Stevens K, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1–89. doi: 10.3310/hta6220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EFS, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr C, Murray E, Stevenson F, et al. Internet interventions for long-term conditions: patient and caregiver quality criteria. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8:e13. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.3.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke S, Brown A, Wallace P. Down your drink: a web-based intervention for people with excessive alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:29–32. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke S, Murray E, Butler C, et al. Internet-based interactive health intervention for the promotion of sensible drinking: patterns of use and potential impact on members of the general public. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, et al. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: a randomized trial. Med Care. 2006;44:964–71. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse Prevention. New York: Guildford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research Council . A Framework for Development and Evaluation of RCTs for Complex Interventions to Improve Health. London: MRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Wilbourne P. Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97:265–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviour. New York: Guildford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People For Change. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murray E. Internet-delivered treatments for long-term conditions: strategies, efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8:261–72. doi: 10.1586/14737167.8.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E, McCambridge J, Khadjesari Z, et al. The DYD-RCT protocol: an online randomised controlled trial of an interactive computer-based intervention compared with a standard information website to reduce alcohol consumption among hazardous drinkers. Biomed Cent (BMC) Public Health. 2007;7:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HQ, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Rankin SH, et al. Supporting cardiac recovery through eHealth technology. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19:200–8. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HQ, Carrieri-Kohlman V, Rankin SH, et al. Internet-based patient education and support interventions: a review of evaluation studies and directions for future research. Comput Biol Med. 2004;34:95–112. doi: 10.1016/S0010-4825(03)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:673–93. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Adams MA. A review of eHealth interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:336–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcohol treatments to client heterogeneity: post-treatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saperstein SL, Atkinson NL, Gold RS. The impact of Internet use for weight loss. Obesity Rev. 2007;8:459–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, et al. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2007;37:319–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Alcohol Treatment Trial Effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems: findings of the randomised UK alcohol treatment trial (UKATT) Brit Med J. 2005;331:541–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7516.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandelanotte C, Spathonis KM, Eakin EG, et al. Website-delivered physical activity interventions: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg MH, Schoones JW, Vliet, et al. Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e26. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.3.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaki EI, Hosier SH, Cox M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a meta-analytic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:328–35. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Wright JA, Shegog R. A review of computer and Internet-based interventions for smoking behavior. Addictive Behav. 2006;31:264–77. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, et al. The effectiveness of web-based vs. non-web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. Time for a change: putting the transtheoretical (stages of change) model to rest. Addiction. 2005;100:1036–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]