Abstract

OBJECTIVE—Despite a high incidence of nocturnal hypoglycemia documented by the use of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), there are no reports in the literature of nocturnal hypoglycemic seizures while a patient is wearing a CGM device.

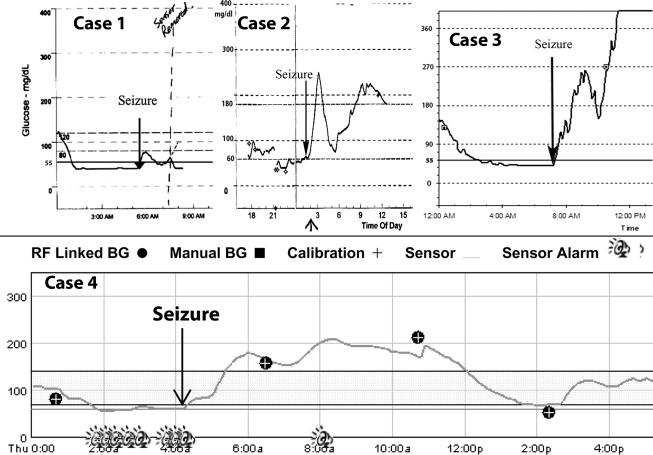

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—In this article, we describe four such cases and assess the duration of nocturnal hypoglycemia before the seizure.

RESULTS—In the cases where patients had a nocturnal hypoglycemic seizure while wearing a CGM device, sensor hypoglycemia (<60 mg/dl) was documented on the CGM record for 2.25–4 h before seizure activity.

CONCLUSIONS—Even with a subcutaneous glucose lag of 18 min when compared with blood glucose measurements, glucose sensors have time to provide clinically meaningful alarms. Current nocturnal hypoglycemic alarms need to be improved, however, since patients can sleep through the current alarm systems.

In the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), intensive diabetes management was associated with an increased frequency of severe hypoglycemic reactions, and more than half of these occurred at night (1). In children, 75% of hypoglycemic seizures occur at night (2). Among patients with type 1 diabetes, there is a 6% lifetime risk of “dead-in-bed” (3), which may in part be a result of severe nocturnal hypoglycemia. Nighttime is the most vulnerable period for hypoglycemia, since sleep blunts the counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia, even in nondiabetic children (4). In young children, there is also concern that severe hypoglycemic events can cause permanent neurologic sequela.

These concerns over nocturnal hypoglycemia are a major reason for people with type 1 diabetes welcoming the possibility of using real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with real-time hypoglycemic alarms. However, there are limitations to current real-time CGM systems. Subcutaneous CGM has a 5- to 18-min delay when compared with glucose levels measured directly from the blood, with greater delays occurring when blood glucose levels are rapidly changing (5,6). It is therefore critical to know how long hypoglycemia can be tolerated before a severe hypoglycemic event (seizure or coma) occurs. Moreover, algorithms could be designed that incorporate both the duration and severity of hypoglycemia and thus decrease the false detection rate.

We have found no published reports of a nocturnal hypoglycemic seizure while a subject was wearing a CGM sensor. We present four such case reports.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

To assess the duration of sensor hypoglycemia preceding a nocturnal hypoglycemic seizure, investigators from around the world were informally asked to submit cases for inclusion in this article. A total of four cases were found: three cases using retrospective CGM and one case using real-time CGM.

RESULTS

Case 1

A 16-year-old male was wearing an original MiniMed CGM system (CGMS) (a retrospective sensor without real-time data or alarms) while he was attending a diabetes camp. Nocturnal hypoglycemia with CGMS glucose values <40 mg/dl was present for 4 h before the seizure. He was diagnosed at age 6 years, his A1C was 7.4%, and he was treated with oral glucose gel.

Case 2

A 12-year-old female wore a MiniMed CGMS-Gold monitor (without real-time data or alarms). She was initially hypoglycemic at 10:00 p.m., and the seizure occurred at 2:00 a.m. During this time, all CGMS values were <60 mg/dl. She was diagnosed at age 8 years, her A1C was 9.0%, she was using Lantus basal insulin, this was her first seizure, and she was treated with glucagon.

Case 3

A 16-year-old girl with type 1 diabetes since age 1 year had unrecognized nocturnal hypoglycemia. Her glucose was <50 mg/dl at 3:00 a.m. and remained <50 mg/dl until 7:00 a.m. when she had a seizure. She was wearing the original CGMS, so there were no hypoglycemic alarms. She was diagnosed at age 1 year, she was using NPH insulin, her A1C was 8.8%, this was her first seizure, and she was treated with glucagon.

Case 4

This case subject was a 17-year-old wearing a MiniMed 722 Paradigm real-time continuous glucose monitor. Although the sensor alarmed for 2 h and 15 min before the seizure occurred, the alarm failed to wake her. She was wearing the pump, which is also the glucose sensor receiver on her pajamas, around her waist and was sleeping under a comforter. When her parents entered her room, they were unable to hear the pump/sensor alarm until they removed the comforter. She was diagnosed at age 7 years, she was using an insulin pump, her A1C was 6.1%, this was her first seizure, and she was treated with oral glucose gel.

CONCLUSIONS

Reviewing these case reports, we were impressed with the long duration of CGM-documented severe hypoglycemia of 2–4 h before a seizure occurred in each of these cases. Two of these records were obtained with the original CGMS, which was reported to have a high frequency of low glucose readings at night (7); however, in our cases, the validity of the CGMS readings was confirmed by the occurrence of hypoglycemic seizures in conjunction with the low nocturnal CGM readings.

To prevent serious events such as seizures, glucose sensors must both detect hypoglycemia and provide a sufficiently robust alarm to awaken the patient or some other member of the household. Schultes et al. (8) reported that people with diabetes have an impaired awakening response to hypoglycemia, and only 1 of 16 subjects with type 1 diabetes awoke to induced nocturnal hypoglycemia, whereas 10 of 16 healthy control subjects were awakened. We have previously videotaped the response of children to GlucoWatch alarms while they were sleeping (9). Although children only awoke to 29% of individual alarms, there were 11 episodes when they were <70 mg/dl, and in each case, they awoke to repeated alarms, indicating that sleeping patients can respond to alarms when they are hypoglycemic. Glucose sensors should have sufficiently robust alarm systems, particularly at night, to insure either the patient or a surrogate is awoken to intervene. Given the likelihood that prolonged or severe hypoglycemia is needed before there is a seizure, hypoglycemia detection algorithms that incorporate the duration of hypoglycemia could have lower false-positive alarm rates and thus be more clinically acceptable. This type of an alarm system may not be applicable during the daytime, where a rapid decrease in blood glucose can result in neurocognitive dysfunction, which can quickly impair performance of important daytime tasks (such as driving).

It is our conclusion that even with the time lag in interstitial glucose readings, there is sufficient time to awaken a patient to prevent a seizure, if they are awoken by the alarm. The alarm systems need to be more effective in awakening subjects. We suggest augmenting the alarm with a bedside device that would turn on a light and transmit the alarm to another location in the house, such as a parent's bedroom.

Figure 1.

Case 1: 15-year-old male wearing an original Minimed CGMS. Case 2: 12-year-old female wearing a Minimed CGMS-Gold monitor. Case 3: 16-year-old female wearing the original Minimed CGMS. Case 4: 17-year-old female wearing a MiniMed 722 Paradigm real-time continuous glucose monitor. Alarm “bell” along time axis at bottom of graph indicates alarming (vibratory and then audio). BG, blood glucose.

Published ahead of print at http://care.diabetesjournals.org on 11 August 2008.

B.B. serves on the Medical Advisory Board and has received research support from Medtronic Minimed. K.K. is a paid speaker/consultant of Medtronic. F.C. has received research funding support, travel support, and honoraria from Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Aventis, Medtronic, and Animas.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.Group DR: The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329:977–986, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis EA, Keating B, Byrne GC, Russell M, Jones TW: Hypoglycemia: incidence and clinical predictors in a large population-based sample of children and adolescents with IDDM. Diabetes Care 20:22–25, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sovik O, Thordarson H: Dead-in-bed syndrome in young diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 22(Suppl. 2):B40–B42, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones TW, Porter P, Sherwin RS, Davis EA, O'Leary P, Fraser F, Byrne G, Stick S, Tamborlane WV: Decreased epinephrine responses to hypoglycemia during sleep. N Engl J Med 338:1657–1662, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyne MS, Silver DM, Kaplan J, Saudek CD: Timing of changes in interstitial and venous blood glucose measured with a continuous subcutaneous glucose sensor. Diabetes 52:2790–2794, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen JK, Djurhuus CB, Gravholt CH, Carus AC, Granild-Jensen J, Orskov H, Christiansen JS: Continuous glucose monitoring in interstitial subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle reflects excursions in cerebral cortex. Diabetes 54:1635–1639, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGowan K, Thomas W, Moran A: Spurious reporting of nocturnal hypoglycemia by CGMS in patients with tightly controlled type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 25:1499–1503, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultes B, Jauch-Chara K, Gais S, Hallschmid M, Reiprich E, Kern W, Oltmanns KM, Peters A, Fehm HL, Born J: Defective awakening response to nocturnal hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. PLoS Med 4:e69, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckingham B, Block J, Burdick J, Kalajian A, Kollman C, Choy M, Wilson DM, Chase P: Response to nocturnal alarms using a real-time glucose sensor. Diabetes Technol Ther 7:440–447, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]