Abstract

Aims

Adiponectin is an adipokine with insulin-sensitizing, anti-atherogenic, anti-inflammatory and angiogenic properties. The aims of this study were to determine whether maternal plasma adiponectin concentrations differ between patients with severe preeclampsia and those with normal pregnancies, and to explore the relationship between plasma adiponectin and the results of Doppler velocimetry of the uterine arteries.

Methods

This case-control study included two groups: (1) patients with severe preeclampsia (n=50) and (2) patients with normal pregnancies (n=150). Pulsed-wave and color Doppler ultrasound examination of the uterine arteries were performed. Plasma adiponectin concentrations were determined by ELISA. Non-parametric statistics were used for analysis.

Results

(1) Patients with severe preeclampsia had a higher median plasma concentration of adiponectin than that of normal pregnant women. (2) The median plasma adiponectin concentration did not differ between women with severe preeclampsia who had a high impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries and those with normal impedance to blood flow. (3) Among patients with normal pregnancies, plasma adiponectin concentrations were negatively correlated with BMI in the first trimester and at sampling.

Conclusions

Women with severe preeclampsia have a higher median plasma concentration of adiponectin than that of normal pregnant women. This may reflect a compensatory feedback mechanism to the metabolically-altered, anti-angiogenic and pro-atherogenic state of severe preeclampsia.

Keywords: Adiponectin, Doppler, Obesity, Preeclampsia, Pregnancy, Uterine artery

INTRODUCTION

Adiponectin is a hormone produced abundantly by adipose tissue [35, 88]. A large body of evidence from experimental and epidemiological studies supports a role of adiponectin in the regulation of insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, inflammatory responses and angiogenesis. In contrast to other hormones produced by adipose tissue (collectively known as adipokines), adiponectin concentrations are negatively correlated with insulin resistance [99, 102], obesity [5, 74], dyslipidemia [53] and hypertension [68]. Low concentrations of adiponectin are also associated with gestational diabetes [14, 44, 71, 73, 97].

In addition to the insulin-sensitizing property of adiponectin, this adipokine has a protective effect against atherosclerosis. Adiponectin suppresses the macrophage-to-foam cell transformation [64] and inhibits the expression and the activity of the class A macrophage scavenger receptor [65]. Furthermore, atherosclerosis that develops in apolipoprotein-E knockout mice can be prevented in 30% of cases by treatment with a vector expressing human adiponectin [63]. Several reports have highlighted the anti-inflammatory properties of adiponectin, including the suppression of macrophage production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [98, 103] interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [95] and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Adiponectin can also exert its anti-inflammatory effects by preventing activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB [66]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that adiponectin stimulates angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro [67, 80].

Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal death. The maternal mortality rate associated with this complication is 1.5/100,000 live births [47]. Most maternal deaths are associated with complications of severe preeclampsia, such as cerebrovascular hemorrhage, renal or hepatic failure, and HELLP syndrome [47]. Thus, the understanding of severe preeclampsia is of major clinical importance. A growing body of evidence indicates that reduced uteroplacental blood flow in the mid-trimester and/or at the time of the onset of disease may play a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia [49, 75, 91]. Preeclampsia is also associated with insulin resistance [34, 85, 96], obesity [19, 82], hyperlipidemia [24, 45] and an exaggerated intravascular inflammatory response [8, 76, 78]. Moreover, patients with a history of preeclampsia are at increased risk for the development of several components of the metabolic syndrome later in life [23, 33, 83, 84]. Because low serum concentrations of adiponectin are strongly associated with these metabolic manifestations, it is tempting to hypothesize that adiponectin plays a role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, and specifically, in the metabolic derangements observed in this syndrome.

Both low [13, 16, 86] and high [27, 29, 37, 46, 59, 70] serum concentrations of adiponectin have been reported in preeclampsia. The results of a longitudinal study may explain these conflicting results. Patients destined to develop preeclampsia are characterized by first trimester low serum concentrations of adiponectin and high serum concentrations of this adipokine after diagnosis, during labor [15]. Similarly, there are limited data and inconsistent findings regarding the association between plasma adiponectin and the metabolic manifestations of preeclampsia, e.g. insulin resistance [15, 37], maternal weight and body mass index (BMI - a proxy of adipose tissue content) [13, 16, 59, 70, 86], and maternal mean blood pressure [16, 59, 61].

This study investigated the association between maternal plasma adiponectin concentrations and Doppler velocimetry of the uterine arteries in patients with severe preeclampsia. We chose to focus on patients with severe preeclampsia, because pathological alterations are more likely to be present in this subset of patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

A case-control study was conducted including patients with severe preeclampsia (n=50) and women with normal pregnancies (n=150). The inclusion criteria for normal pregnant women were: (1) singleton pregnancies; 92) no prior abnormal metabolic or medical conditions; (3) no obstetrical, maternal, or fetal complications during pregnancy and (4) delivery of a healthy neonate at term with a birthweight appropriate for gestational age (>10th and <90th percentile).

Definitions

Severe preeclampsia was defined as severe hypertension (diastolic blood pressure > 110 mmHg) plus mild proteinuria, or mild hypertension and severe proteinuria (a 24-h urine sample containing > 3.5 g of protein or a urine specimen with > 3+ protein by dipstick measurement on two occasions), or severe hypertension plus severe proteinuria [81]. Patients with an abnormal liver function test (aspartate aminotransferase >70 IU/L) plus thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/cm3) were also classified as having severe preeclampsia [2]. Normal pregnant women were matched by gestational age at enrollment with those of preeclampsia, in a proportion of 3:1.

Overweight women have a high risk of developing glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia and coronary heart disease [1, 72]. Thus, we subdivided our study groups using the first trimester BMI according to the definitions of the World Health Organization (Normal weight: BMI ≥18.5 to <25, and Overweight: BMI ≥25) [17].

Upon enrollment, pulsed-wave and color Doppler ultrasound examination of the uterine arteries was performed in 28 women with preeclampsia with a real-time scanner (ACUSON Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA) equipped with a 3.5 MHz or a 5 MHz curvilinear probe. Abnormal uterine artery Doppler velocimetry was defined in the presence of a mean pulsatility index from both the left and the right uterine arteries above the 95th percentile for gestational age and/or in the presence of bilateral diastolic notches in the Doppler waveforms of the uterine arteries [3].

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the collection of maternal blood samples. The utilization of samples for research purposes was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Many of these samples have been employed to study the biology of inflammation, hemostasis, angiogenesis regulation, and growth factor concentrations in non-pregnant women, normal pregnant women and those with pregnancy complications.

Sample collection and adiponectin immunoassay

Blood samples were collected during the third trimester into vials containing ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid, centrifuged at 1300 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma obtained was stored at −70°C until analysis. Plasma adiponectin concentrations were determined with the Human Adiponectin ELISA (LINCO Research Inc, St Charles, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The sensitivity of the assay was 0.91 ng/mL and the coefficients of intra- and inter-assay variation were 4.6% and 6.6%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated for every patient using the weight and height in the first trimester and at the time of sample collection according to the following formula: BMI= Weight (kg)/[Height (m)]2. Normality of the data distribution was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were presented as mean ±SD for those parameters which were normally distributed and parametric tests were used for analysis. The plasma adiponectin concentrations were not normally distributed. Thus, non-parametric tests were used for analysis. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare medians for continuous variables between two groups and the X2-test was used to test differences in proportions. The statistical software package SPSS 12 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Plasma adiponectin was detectable in all subjects. Table 1 displays the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups. No significant differences were observed in mean maternal age, first trimester BMI, and gestational age at sample collection between patients with severe preeclampsia and normal pregnant women. As expected, patients with severe preeclampsia delivered earlier than normal pregnant women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study groups.

| Control (n=150) | Preeclampsia | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (mean ± SD, years) | 20 ± 12 | 24 ± 9.9 | NS |

| First Trimester BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 3.7 | 24.9 ± 4.2 | NS |

| Nulliparity (%, n) | 36% (54/150) | 62% (31/50) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age at sample collection (mean ± SD, weeks) | 32 ± 3.6 | 32 ± 3.5 | NS |

| Gestational age at delivery (mean ± SD, weeks) | 39 ± 1.1 | 33 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or percentage (proportion)

BMI: Body Mass Index; SD: Standard Deviation; NS: Not significant

Adiponectin concentrations in patients with preeclampsia and normal pregnancies

Plasma adiponectin concentrations of normal pregnant women showed a significant negative correlation with the BMI at sample collection (Spearman’s rho = −0.27, P=0.001), and with first trimester BMI (Spearman’s rho = −0.25, P=0.001). This relationship was not observed in the group of patients with severe preeclampsia. Likewise, when the analysis included only over-weight patients, there was no correlation between plasma adiponectin and BMI.

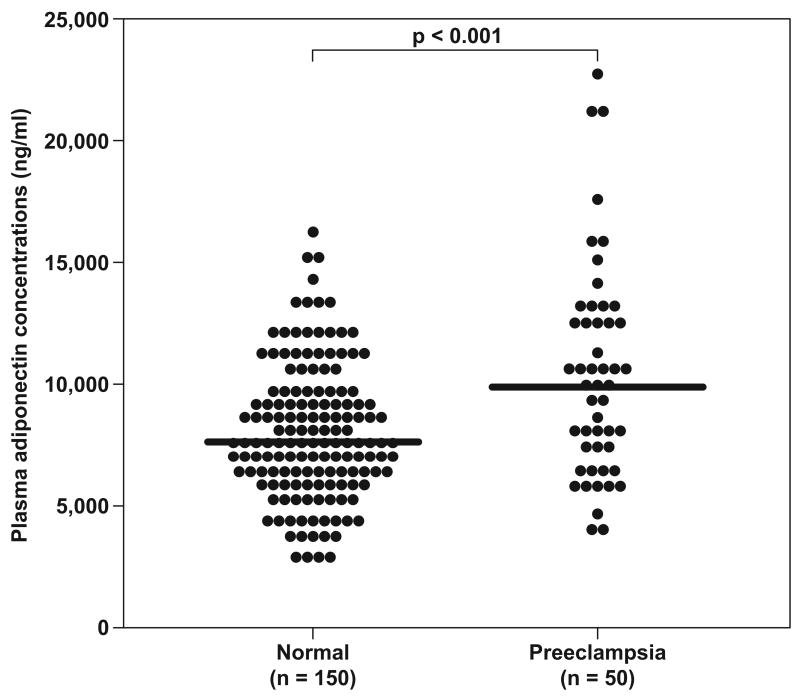

When all pregnant women were pooled together, those with severe preeclampsia had a higher median plasma concentration of adiponectin than that of normal pregnant women (median: 9,978 ng/mL, range: 3,989 – 23,220 vs. median: 7,629 ng/mL, range: 2,772 –16,340, respectively; P<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adiponectin concentrations in normal pregnant women and patients with preeclampsia. Plasma adiponectin concentrations of women with preeclampsia showed increased concentrations compared to normal pregnant women.

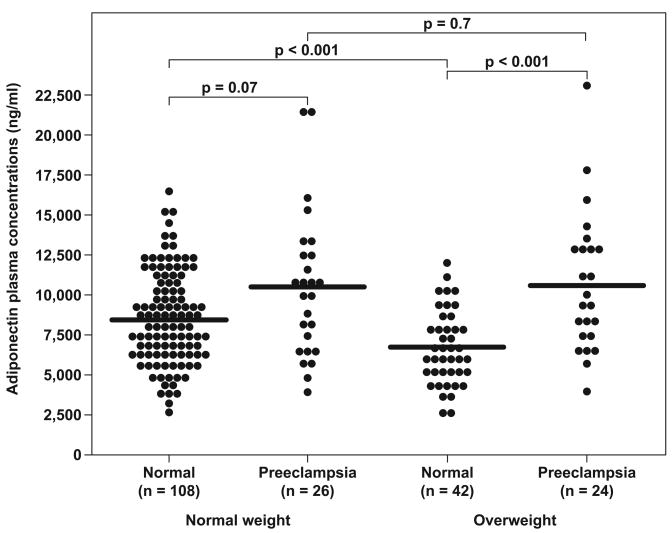

Among women with uncomplicated pregnancies, those who were overweight had a lower median adiponectin concentration than those of normal weight (median: 6,469 ng/mL, range: 2,820 – 11,570 vs. median: 8,480 ng/mL, range: 2,772 – 16,340, respectively; P<0.001) (Figure 2). In contrast, among patients with severe preeclampsia, overweight and normal weight women had similar median plasma adiponectin concentrations (median: 9,632 ng/mL, range: 3,989 – 23,220 vs. median: 10,315 ng/mL, range: 4,098 –21,560, respectively; P=0.7) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of adiponectin concentrations in normal and preeclamptic patients stratified by weight classification.

Among women with uncomplicated pregnancies, those who were overweight had a lower median adiponectin concentration than those of normal weight. In contrast, among patients with severe preeclampsia, overweight and normal weight women had similar median plasma adiponectin concentrations.

Adiponectin concentrations in normal weight and overweight patients

Among normal weight women, there was no significant difference in the median plasma adiponectin concentration between those with severe preeclampsia and those with a normal pregnancy (median: 10,315 ng/mL, range: 4,098 – 21,560 vs. median: 8,480 ng/mL, range: 2,772 – 16,340, respectively; P=0.07) (Figure 2). However, when the analysis was confined to overweight women, the median plasma adiponectin concentration was significantly higher in patients with severe preeclampsia than in patients with normal pregnancy (median: 9,632 ng/mL, range: 3,989 – 23,220 vs. median: 6,496 ng/mL, range: 2,820 – 11,570, respectively; P=0.001) (Figure 2).

Adiponectin and Doppler velocimetry studies in women with severe preeclampsia

Abnormal Doppler findings were detected in 22 of 28 patients with severe preeclampsia. There was no significant difference in the median maternal plasma adiponectin concentration between women with severe preeclampsia with high impedance to blood flow in the uterine arteries and those with normal impedance to blood flow.

DISCUSSION

Principal findings of the study

(1) When all women were pooled together, those with severe preeclampsia had a higher median plasma adiponectin concentration than that of women with uncomplicated pregnancies; (2) Among women with uncomplicated pregnancies, those who were overweight had a lower median adiponectin concentration than those who were of normal weight. In contrast, among patients with severe preeclampsia, overweight and normal weight women, had similar adiponectin concentrations; (3) Abnormal Doppler studies in the uterine arteries were not associated with alterations in median adiponectin concentrations in patients with severe preeclampsia.

The physiological role of adiponectin

Adiponectin is a member of a growing group of proteins secreted by adipose tissue termed adipokines. Discovered in 1995–1996 [31, 50, 58, 77], adiponectin is a plasma protein produced abundantly by adipose tissue and which circulates at very high concentrations [31, 58, 77]. In contrast to other adipokines (e.g. leptin, TNF-α, and IL-6) adiponectin plasma concentrations are paradoxically lower in obese subjects than in normal weight. Moreover, weight reduction in obese individuals is accompanied by an increase in plasma adiponectin concentrations [20, 101], suggesting that adipose tissue inhibits adiponectin production.

Several lines of evidence indicate that adiponectin is an important regulator of insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. Such evidence includes: (1) insulin resistance and plasma adiponectin concentrations are inversely correlated [30, 93]; (2) genetic variation in the adiponectin gene are associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes [26]; and (3) administration of recombinant adiponectin to both wild-type and insulin-resistant mice results in a significant decrease in plasma glucose concentrations [9, 22, 26]. The reduction in plasma glucose is independent of plasma insulin concentrations and has also been observed in mice with deficient insulin secretion, indicating that the effect of adiponectin is probably mediated by enhancing insulin function.

Adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects, such as inhibition of endothelial nuclear factor-κB signaling [66], phagocytic activity, and TNF-α production by macrophages [103]. Other studies have highlighted the anti-atherogenic properties of adiponectin [62, 64, 66], as well as the angiogenic effect of this hormone [67, 80].

Adiponectin and vascular dysfunction

Adiponectin has been consistently shown to have protective effects on the vasculature. The following experimental evidence supports a role of adiponectin in the prevention of atherosclerosis: (1) adiponectin, at physiological concentrations, inhibits TNF-α-induced monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells, which has been implicated in atherogenesis [64, 66]; (2) adiponectin reduces the expression of various adhesion molecules, including vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and E-selectin [64], which endothelial cells express in the early stages of atherosclerosis; (3) in vitro studies have demonstrated that human adiponectin inhibits macrophage-to-foam cell transformation, and macrophages exposed to adiponectin have a reduced intracellular cholesteryl ester content [62]; (4) adiponectin can suppress the proliferation of smooth muscle cells, alterations of which are important for the formation of atherogenic lesions [4]; (5) adiponectin accumulates in lesions of injured large vessels, but not in intact vascular walls [62]; and (6) an injury to arteries in adiponectin-knockout mice, but not to wild-type mice, results in severe neointimal thickening and increased proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [52]. Moreover, treatment with adiponectin may prevent this pathological condition [52]. Taken together, these findings indicate that adiponectin has a role, either direct or indirectly, in the regulation and integrity of the vascular system.

Adiponectin and Doppler studies

Few studies have addressed the relationships between plasma/serum adiponectin concentrations and Doppler studies of blood vessels. Serum adiponectin concentrations are positively correlated with coronary flow velocity reserve in healthy young men [39]. Coronary flow velocity reserve is a measure of coronary artery integrity and cardiac microvascular function, and it is defined as the ratio between coronary blood flow velocities before and during pharmacologically-induced vasodilatation [7, 18].

One study investigated the association between maternal plasma adiponectin concentrations and Doppler studies of the uterine arteries in 24 pregnant patients during the second trimester (18–21 weeks of gestation) [21]. Six patients had normal Doppler findings, whereas 18 patients had abnormal Doppler results, defined as bilateral notching and/or the mean PI of both arteries greater than the 90th percentile (mean PI >1.45) of the reference group. Mean plasma adiponectin concentrations were significantly higher in patients with abnormal Doppler findings than in those with normal findings. Eleven of the 18 patients with abnormal Doppler studies developed preeclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction later in the pregnancy. Of note, the mean plasma adiponectin concentration did not differ between patients with abnormal uterine blood flow who developed complications and those who did not [21].

Why is severe preeclampsia characterized by high plasma concentrations of adiponectin?

The findings of the present study indicate that the median plasma adiponectin concentration is higher in patients with severe preeclampsia than in normal pregnant women. Our findings are in agreement with some previous reports [27, 29, 37, 46, 59, 70], but contrast with other observations, in which serum adiponectin concentration is lower in patients with preeclampsia than in normal pregnant women [13, 16, 86]. Differences in study design and sample size may contribute to the discrepancies among studies. Our study includes the largest number of patients with severe preeclampsia in the third trimester and normal pregnant women reported thus far. Previous reports have included patients with both mild and severe preeclampsia [13, 16, 86] and only in one study were all patients studied in the third trimester [86].

Insulin resistance, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and an exaggerated inflammatory response are associated with low adiponectin concentrations in the non-pregnant state. Preeclampsia, a disease of pregnancy, is associated with these conditions with accompanying high serum concentrations of adiponectin. The mechanisms underlying the paradoxical increase in serum adiponectin in patients with preeclampsia have not been elucidated. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this finding in preeclampsia:

Impaired renal function in patients with severe preeclampsia

Because adiponectin is secreted into the urine [41], renal dysfunction may increase its serum concentrations. Indeed, patients with end-stage renal failure have higher serum concentrations of adiponectin than do normal subjects [41, 104]. However, there is no evidence to support this association in patients with preeclampsia. Moreover, although the subjects included in our study had proteinuria associated with preeclampsia, none had renal failure.

Overproduction and/or exaggerated secretion of adiponectin by adipocytes

Preeclampsia is associated with increased concentrations of adipocyte-derived metabolites such as free fatty acids [32, 57], TNF-α [28, 94], IL-6 [48, 87], leptin [55, 56] and others. Thus, high adiponectin concentrations in preeclampsia may be another manifestation of adipocyte activation.

Adiponectin resistance in patients with preeclampsia

It has been suggested that serum concentrations of adiponectin are increased as part of a compensatory mechanism for decreased expression of adiponectin receptors in muscles and adipose tissue [35, 36, 89]. Of note, insulin resistance, a well-known characteristic of preeclampsia, has been associated with decreased expression of adiponectin receptors [35]. However, there are no data to suggest that muscles or adipose tissue obtained from patients with preeclampsia have low expression of adiponectin receptors.

A counter-regulatory response aimed at moderating endothelial damage and metabolic alterations in preeclampsia

The insulin sensitizing, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherogenic and angiogenic properties of adiponectin have led to the conclusion that it has a protective effect. Preeclampsia is closely linked to various metabolic changes, altered inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction and, recently, to an anti-angiogenic state [10, 40, 43, 51, 54, 69, 90]. Thus, given the noticeable overlap between the physiological functions of adiponectin and the pathological alterations in preeclampsia, it is tempting to postulate that increased adiponectin concentrations in patients with preeclampsia may represent a compensatory mechanism. Teleologically, increased concentrations of adiponectin can be beneficial to the mother by preventing excessive fat accumulation [70, 100] and to the fetus since lipolysis can increase triglyceride and free fatty acid availability. Conversely, adiponectin can also decrease maternal glucose production by the inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis [12] and thus negatively affect the fetus through decreased glucose availability.

Why are abnormal Doppler findings not accompanied by alterations in maternal plasma adiponectin?

The finding that patients with severe preeclampsia and an abnormal uterine arteries Doppler velocimetry have comparable median maternal plasma concentrations of adiponectin with those with normal uterine artery Doppler is novel. Of note, in this study patients with abnormal Doppler velocimetry did not have a more severe clinical form of preeclampsia. The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure, proteinuria, platelets count and liver function test did not differ significantly between the two groups. We hypothesize that high concentrations of plasma adiponectin in patients with preeclampsia are a counter regulatory phenomena and, thus, a reflection of the severity of the disease.

Obesity, pregnancy and preeclampsia – is adiponectin the missing link?

The association between an overweight state, obesity and preeclampsia is well documented [6, 11, 81, 92]. A 2 to 4-fold higher incidence of preeclampsia is reported in obese pregnancies [42, 79]. A meta-analysis of maternal BMI and preeclampsia showed that the risk doubled with each 5–7 kg/m2 increase in BMI [60]. The underlying mechanisms for this relationship are still not completely understood, however, several mechanisms have been proposed: 1) excess adipose tissue can produce a hypoxic state by increasing the concentrations of glycosylated hemoglobin and decreasing the affinity for oxygen. This relative hypoxemia can cause abnormal placentation [38], 2) subclinical inflammation is one of the hallmarks of obesity, since an increase in body fat is associated with elevated cytokine levels and subclinical inflammation [25]. An exaggerated inflammatory response is one of the characteristics of preeclampsia, thus those patients with an inflammatory response in early pregnancy are prone to develop preeclampsia; 3) obese pregnant women have a 3 to 10-fold higher risk of preexisting hypertension or diabetes compared to those of normal weight [79], and both conditions are associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia.

This study indicates that in patients with severe preeclampsia, the median plasma adiponectin concentration did not differ between overweight and normal weight women. On the other hand, among women with normal pregnancy, an overweight state was associated with lower median plasma adiponectin concentrations. Thus, while patients who were overweight had the anticipated association with low plasma adiponectin concentrations, in normal pregnant women, this relationship was disrupted in severe preeclampsia. These finding suggests that adiponectin may have a role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia and that the alterations in its concentrations in pregnant women with severe preeclampsia are not just a reflection of metabolic changes. Otherwise, excess adipose tissue should have some effect on the concentrations of this hormone. Consistent with this hypothesis is that the median adiponectin concentrations are significantly higher in overweight patients with preeclampsia than in overweight women with normal pregnancy. This finding may indicate that plasma adiponectin regulation is altered in severe preeclampsia as compared with normal pregnancy.

In conclusion, the results reported herein demonstrate that women with severe preeclampsia have higher plasma concentrations of adiponectin than those with normal pregnancy. We propose that these changes in plasma adiponectin concentration may be part of the compensatory mechanisms of the adipose tissue to the metabolically-altered, anti-angiogenic, pro-atherogenic state of severe preeclampsia.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

Reference List

- 1.Abbasi F, Brown BW, Jr, Lamendola C, McLaughlin T, Reaven GM. Relationship between obesity, insulin resistance, and coronary heart disease risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:937–943. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACOG technical bulletin. Hypertension in pregnancy. Number 219--January 1996 (replaces no. 91, February 1986). Committee on Technical Bulletins of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1996;53:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albaiges G, Missfelder-Lobos H, Lees C, Parra M, Nicolaides KH. One-stage screening for pregnancy complications by color Doppler assessment of the uterine arteries at 23 weeks’ gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:559–564. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00946-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin acts as a platelet-derived growth factor-BB-binding protein and regulates growth factor-induced common postreceptor signal in vascular smooth muscle cell. Circulation. 2002;105:2893–2898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018622.84402.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:79–83. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeten JM, Bukusi EA, Lambe M. Pregnancy complications and outcomes among overweight and obese nulliparous women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:436–440. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgart D, Haude M, Liu F, Ge J, Goerge G, Erbel R. Current concepts of coronary flow reserve for clinical decision making during cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 1998;136:136–149. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benyo DF, Smarason A, Redman CW, Sims C, Conrad KP. Expression of inflammatory cytokines in placentas from women with preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2505–2512. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2001;7:947–953. doi: 10.1038/90992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Espinoza J, Bujold E, Mee KY, Goncalves LF, et al. Evidence supporting a role for blockade of the vascular endothelial growth factor system in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Young Investigator Award. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Kramer MS. Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:147–152. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Combs TP, Berg AH, Obici S, Scherer PE, Rossetti L. Endogenous glucose production is inhibited by the adipose-derived protein Acrp30. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1875–1881. doi: 10.1172/JCI14120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortelazzi D, Corbetta S, Ronzoni S, Pelle F, Marconi A, Cozzi V, et al. Maternal and foetal resistin and adiponectin concentrations in normal and complicated pregnancies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cseh K, Baranyi E, Melczer Z, Kaszas E, Palik E, Winkler G. Plasma adiponectin and pregnancy-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:274–275. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Anna R, Baviera G, Corrado F, Giordano D, De VA, Nicocia G, et al. Adiponectin and insulin resistance in early- and late-onset pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2006;113:1264–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Anna R, Baviera G, Corrado F, Giordano D, Di Benedetto A, Jasonni VM. Plasma adiponectin concentration in early pregnancy and subsequent risk of hypertensive disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:340–344. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000168441.79050.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diet. nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;916:i-149. backcover. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimitrow PP. Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography - noninvasive diagnostic window for coronary flow reserve assessment. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2003;1:4–4. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskenazi B, Fenster L, Sidney S. A multivariate analysis of risk factors for preeclampsia. JAMA. 1991;266:237–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Masella M, Marfella R, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1799–1804. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fasshauer M, Bluher M, Stumvoll M, Tonessen P, Faber R, Stepan H. Differential regulation of visfatin and adiponectin in pregnancies with normal and abnormal placental function. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:434–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fruebis J, Tsao TS, Javorschi S, Ebbets-Reed D, Erickson MR, Yen FT, et al. Proteolytic cleavage product of 30-kDa adipocyte complement-related protein increases fatty acid oxidation in muscle and causes weight loss in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2005–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041591798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girouard J, Giguere Y, Moutquin JM, Forest JC. Previous hypertensive disease of pregnancy is associated with alterations of markers of insulin resistance. Hypertension. 2007;49:1056–1062. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gratacos E, Casals E, Sanllehy C, Cararach V, Alonso PL, Fortuny A. Variation in lipid levels during pregnancy in women with different types of hypertension. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996;75:896–901. doi: 10.3109/00016349609055024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:461S–465S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hara K, Boutin P, Mori Y, Tobe K, Dina C, Yasuda K, et al. Genetic variation in the gene encoding adiponectin is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetes. 2002;51:536–540. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haugen F, Ranheim T, Harsem NK, Lips E, Staff AC, Drevon CA. Increased plasma levels of adipokines in preeclampsia: relationship to placenta and adipose tissue gene expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E326–E333. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00020.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayashi M, Ueda Y, Yamaguchi T, Sohma R, Shibazaki M, Ohkura T, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the placenta is not elevated in pre-eclamptic patients despite its elevation in peripheral blood. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;53:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendler I, Blackwell SC, Mehta SH, Whitty JE, Russell E, Sorokin Y, et al. The levels of leptin, adiponectin, and resistin in normal weight, overweight, and obese pregnant women with and without preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:979–983. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotta K, Funahashi T, Arita Y, Takahashi M, Matsuda M, Okamoto Y, et al. Plasma concentrations of a novel, adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in type 2 diabetic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1595–1599. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10697–10703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK, Evans RW, Hauth BA, Sims CJ, Roberts JM. Fasting serum triglycerides, free fatty acids, and malondialdehyde are increased in preeclampsia, are positively correlated, and decrease within 48 hours post partum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:975–982. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, Lie RT. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001;323:1213–1217. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joffe GM, Esterlitz JR, Levine RJ, Clemens JD, Ewell MG, Sibai BM, et al. The relationship between abnormal glucose tolerance and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in healthy nulliparous women. Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:439–451. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1784–1792. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kajantie E, Kaaja R, Ylikorkala O, Andersson S, Laivuori H. Adiponectin concentrations in maternal serum: elevated in preeclampsia but unrelated to insulin sensitivity. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King JC. Maternal obesity, metabolism, and pregnancy outcomes. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006;26:271–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiviniemi TO, Snapir A, Saraste M, Toikka JO, Raitakari OT, Ahotupa M, et al. Determinants of coronary flow velocity reserve in healthy young men. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H564–H569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00915.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koga K, Osuga Y, Yoshino O, Hirota Y, Ruimeng X, Hirata T, et al. Elevated serum soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sVEGFR-1) levels in women with preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2348–2351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshimura J, Fujita H, Narita T, Shimotomai T, Hosoba M, Yoshioka N, et al. Urinary adiponectin excretion is increased in patients with overt diabetic nephropathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumari AS. Pregnancy outcome in women with morbid obesity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;73:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu KF, Maynard SE, Sachs BP, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lopez-Bermejo A, Fernandez-Real JM, Garrido E, Rovira R, Brichs R, Genaro P, et al. Maternal soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor type 2 (sTNFR2) and adiponectin are both related to blood pressure during gestation and infant’s birthweight. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;61:544–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorentzen B, Drevon CA, Endresen MJ, Henriksen T. Fatty acid pattern of esterified and free fatty acids in sera of women with normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:530–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu D, Yang X, Wu Y, Wang H, Huang H, Dong M. Serum adiponectin, leptin and soluble leptin receptor in pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:533–538. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madazli R, Aydin S, Uludag S, Vildan O, Tolun N. Maternal plasma levels of cytokines in normal and preeclamptic pregnancies and their relationship with diastolic blood pressure and fibronectin levels. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:797–802. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madazli R, Somunkiran A, Calay Z, Ilvan S, Aksu MF. Histomorphology of the placenta and the placental bed of growth restricted foetuses and correlation with the Doppler velocimetries of the uterine and umbilical arteries. Placenta. 2003;24:510–516. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maeda K, Okubo K, Shimomura I, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Matsubara K. cDNA cloning and expression of a novel adipose specific collagen-like factor, apM1 (AdiPose Most abundant Gene transcript 1) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;221:286–289. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masuyama H, Nakatsukasa H, Takamoto N, Hiramatsu Y. Correlation between soluble endoglin, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor -1 and adipocytokines in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2672–2679. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsuda M, Shimomura I, Sata M, Arita Y, Nishida M, Maeda N, et al. Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis. The missing link of adipo-vascular axis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37487–37491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsushita K, Yatsuya H, Tamakoshi K, Wada K, Otsuka R, Takefuji S, et al. Comparison of circulating adiponectin and proinflammatory markers regarding their association with metabolic syndrome in Japanese men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:871–876. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000208363.85388.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCarthy JF, Misra DN, Roberts JM. Maternal plasma leptin is increased in preeclampsia and positively correlates with fetal cord concentration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:731–736. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mise H, Sagawa N, Matsumoto T, Yura S, Nanno H, Itoh H, et al. Augmented placental production of leptin in preeclampsia: possible involvement of placental hypoxia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3225–3229. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murai JT, Muzykanskiy E, Taylor RN. Maternal and fetal modulators of lipid metabolism correlate with the development of preeclampsia. Metabolism. 1997;46:963–967. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakano Y, Tobe T, Choi-Miura NH, Mazda T, Tomita M. Isolation and characterization of GBP28, a novel gelatin-binding protein purified from human plasma. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;120:803–812. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naruse K, Yamasaki M, Umekage H, Sado T, Sakamoto Y, Morikawa H. Peripheral blood concentrations of adiponectin, an adipocyte-specific plasma protein, in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;65:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Brien TE, Ray JG, Chan WS. Maternal body mass index and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic overview. Epidemiology. 2003;14:368–374. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200305000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Odden N, Henriksen T, Holter E, Grete SA, Tjade T, Morkrid L. Serum adiponectin concentration prior to clinical onset of preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2006;25:129–142. doi: 10.1080/10641950600745475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okamoto Y, Arita Y, Nishida M, Muraguchi M, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, et al. An adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, adheres to injured vascular walls. Horm Metab Res. 2000;32:47–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Nishida M, Arita Y, Kumada M, et al. Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2767–2770. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042707.50032.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, et al. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. 1999;100:2473–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.25.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Nishida M, Matsuyama A, Okamoto Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:1057–1063. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Okamoto Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, et al. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived plasma protein, inhibits endothelial NF-kappaB signaling through a cAMP-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2000;102:1296–1301. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ouchi N, Kobayashi H, Kihara S, Kumada M, Sato K, Inoue T, et al. Adiponectin stimulates angiogenesis by promoting cross-talk between AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt signaling in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1304–1309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310389200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ouchi N, Ohishi M, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Nakamura T, Nagaretani H, et al. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with impaired vasoreactivity. Hypertension. 2003;42:231–234. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000083488.67550.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park CW, Park JS, Shim SS, Jun JK, Yoon BH, Romero R. An elevated maternal plasma, but not amniotic fluid, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) at the time of mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis is a risk factor for preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:984–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramsay JE, Jamieson N, Greer IA, Sattar N. Paradoxical elevation in adiponectin concentrations in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2003;42:891–894. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000095981.92542.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ranheim T, Haugen F, Staff AC, Braekke K, Harsem NK, Drevon CA. Adiponectin is reduced in gestational diabetes mellitus in normal weight women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:341–347. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reaven G, Abbasi F, McLaughlin T. Obesity, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:207–223. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B. Reduced adiponectin concentration in women with gestational diabetes: a potential factor in progression to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:799–800. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryo M, Nakamura T, Kihara S, Kumada M, Shibazaki S, Takahashi M, et al. Adiponectin as a biomarker of the metabolic syndrome. Circ J. 2004;68:975–981. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sagol S, Ozkinay E, Oztekin K, Ozdemir N. The comparison of uterine artery Doppler velocimetry with the histopathology of the placental bed. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39:324–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1999.tb03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saito S, Umekage H, Sakamoto Y, Sakai M, Tanebe K, Sasaki Y, et al. Increased T-helper-1-type immunity and decreased T-helper-2-type immunity in patients with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;41:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1999.tb00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26746–26749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schiff E, Friedman SA, Baumann P, Sibai BM, Romero R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in pregnancies associated with preeclampsia or small-for-gestational-age newborns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW, et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287, 213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1175–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shibata R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Sato K, Funahashi T, Walsh K. Adiponectin stimulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia through stimulation of amp-activated protein kinase signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28670–28674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sibai BM, Ewell M, Levine RJ, Klebanoff MA, Esterlitz J, Catalano PM, et al. Risk factors associated with preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women. The Calcium for Preeclampsia Prevention (CPEP) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1003–1010. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sibai BM, Gordon T, Thom E, Caritis SN, Klebanoff M, McNellis D, et al. Risk factors for preeclampsia in healthy nulliparous women: a prospective multicenter study. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:642–648. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90586-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sibai BM, Sarinoglu C, Mercer BM. Eclampsia. VII. Pregnancy outcome after eclampsia and long-term prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1757–1761. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91566-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith GC, Pell JP, Walsh D. Pregnancy complications and maternal risk of ischaemic heart disease: a retrospective cohort study of 129, 290 births. Lancet. 2001;357:2002–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Solomon CG, Seely EW. Brief review: hypertension in pregnancy : a manifestation of the insulin resistance syndrome? Hypertension. 2001;37:232–239. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Suwaki N, Masuyama H, Nakatsukasa H, Masumoto A, Sumida Y, Takamoto N, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia and circulating angiogenic factors in overweight patients complicated with pre-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takacs P, Green KL, Nikaeo A, Kauma SW. Increased vascular endothelial cell production of interleukin-6 in severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:740–744. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trujillo ME, Scherer PE. Adiponectin--journey from an adipocyte secretory protein to biomarker of the metabolic syndrome. J Intern Med. 2005;257:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tsuchida A, Yamauchi T, Ito Y, Hada Y, Maki T, Takekawa S, et al. Insulin/Foxo1 pathway regulates expression levels of adiponectin receptors and adiponectin sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30817–30822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Voigt HJ, Becker V. Doppler flow measurements and histomorphology of the placental bed in uteroplacental insufficiency. J Perinat Med. 1992;20:139–147. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1992.20.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al. Obesity, obstetric complications and cesarean delivery rate--a population-based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1930–1935. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Williams MA, Farrand A, Mittendorf R, Sorensen TK, Zingheim RW, O’Reilly GC, et al. Maternal second trimester serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha-soluble receptor p55 (sTNFp55) and subsequent risk of preeclampsia. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:323–329. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wolf AM, Wolf D, Rumpold H, Enrich B, Tilg H. Adiponectin induces the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA in human leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wolf M, Sandler L, Munoz K, Hsu K, Ecker JL, Thadhani R. First trimester insulin resistance and subsequent preeclampsia: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1563–1568. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Worda C, Leipold H, Gruber C, Kautzky-Willer A, Knofler M, Bancher-Todesca D. Decreased plasma adiponectin concentrations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:2120–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wulster-Radcliffe MC, Ajuwon KM, Wang J, Christian JA, Spurlock ME. Adiponectin differentially regulates cytokines in porcine macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:924–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamamoto Y, Hirose H, Saito I, Nishikai K, Saruta T. Adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived protein, predicts future insulin resistance: two-year follow-up study in Japanese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:87–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2002;8:1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang WS, Lee WJ, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Matsuzawa Y, Chao CL, et al. Weight reduction increases plasma levels of an adipose-derived anti-inflammatory protein, adiponectin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3815–3819. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yatagai T, Nishida Y, Nagasaka S, Nakamura T, Tokuyama K, Shindo M, et al. Relationship between exercise training-induced increase in insulin sensitivity and adiponectinemia in healthy men. Endocr J. 2003;50:233–238. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.50.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yokota T, Oritani K, Takahashi I, Ishikawa J, Matsuyama A, Ouchi N, et al. Adiponectin, a new member of the family of soluble defense collagens, negatively regulates the growth of myelomonocytic progenitors and the functions of macrophages. Blood. 2000;96:1723–1732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Benedetto FA, Cutrupi S, Parlongo S, et al. Adiponectin, metabolic risk factors, and cardiovascular events among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:134–141. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V131134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]