Abstract

Perforation and dilation of the persistent hymen in an alpaca and a llama, detected by vaginal examination and endoscopy, was achieved by use of a sigmoidoscope and incremental dilation using cylindrical instruments to a maximum diameter of 38 mm. Outcome and subsequent fertility are dependent on length of time the obstruction has been present and secondary uterine disease.

Résumé

Infertilité associée à un hymen persistant chez un alpaca et un lama. Un hymen persistant a été détecté chez un alpaca et un lama par examen vaginal et endoscopie. Une perforation et une dilatation ont été respectivement réalisées par utilisation d’un sigmoïdoscope et par des instruments cylindriques d’un diamètre croissant allant jusqu’à un maximum de 38 mm. Le résultat et la fertilité subséquents sont dépendants de la durée de l’obstruction et de la maladie utérine secondaire.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Infertility associated with a persistent hymen in South American camelids has not been documented in the peer-reviewed literature. Persistent hymen in camelids has been described in textbooks, and treatment by digital perforation is recommended. However, complete case descriptions, uterine fluid cytology, ultrasonographic evaluation, outcomes, and discussion of potential novel therapies have not been reported. The aim of this report was to document the disease condition, instrument-assisted approach to perforation and dilation, and the variable outcome.

Case description

Case 1

A 3-year-old female alpaca was presented for evaluation of infertility and rectal prolapse. Eight months prior to referral, the alpaca had been receptive to a male and breeding was attempted, but the animal failed to become pregnant. At the time of ultrasound examination for pregnancy diagnosis, 5 mo before presentation, the referring veterinarian performed vaginoscopy and detected a membrane in the vagina that was completely obstructing the entrance to the vaginal vault. This membrane was perforated and dilated using digital pressure. Attempts at rebreeding continued, but the alpaca was not receptive to the male. Tenesmus developed 3 d prior to presentation and was associated with an intermittent grade 1 (out of 4) rectal prolapse (1).

Physical examination at presentation was unremarkable except for mild edema in the perineal region and a dilated anal sphincter. Hematology and serum chemistry data were within normal reference ranges except for a mild anemia [hematocrit 25.4%; reference interval (RI) 28–39%] and hyperfibrinogenemia (6 mmol/L; RI 1–4 mmol/L). Palpation per rectum revealed a large, firm mass ventral to the rectum that extended cranially out of reach from the pelvic canal. Transabdominal and transrectal ultrasonography identified this mass as being confluent with large hyperechoic (grade 1 out of 4) (2) fluid loops in the caudal abdomen (9–12 cm in diameter). The ultrasonographic appearance of these loops was consistent with a fluid-filled uterus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transabdominal ultrasonographic appearance of fluid-filled uterus (1) in the alpaca (case 1). Each hatched line of the left of the image represents 1 cm.

The alpaca was sedated with diazepam (Hospira, Lake Forest, Illinois, USA) 0.2 mg/kg IV and butorphanol tartrate (Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa, USA) 0.1 mg/kg IV for endoscopic examination of the reproductive and urinary tract. Initial attempts to visualize the vagina resulted in endoscope entry into the urethra and bladder, which were normal in appearance. The cervix could not be visualized. Instead, at 4 cm cranial to the vaginal opening, there was an imperforate wall of mucosal tissue that was of similar appearance to the adjacent tissue.

A diagnosis of a persistent hymen and mucometra was made. The alpaca was restrained in a standing position and perforation of the mucosal tissue was achieved using gentle manual pressure with a fiberoptic sigmoidoscope (19-mm external diameter, 15-cm length; Welch Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, New York, USA). Approximately 10 L of viscous opaque white liquid spontaneously drained from the vagina after patency was achieved (Figure 2). Cytological examination of the fluid revealed a high cellularity consisting of degenerate neutrophils with basophilic (proteinaceous) and granular debris. No bacteria were identified. Due to breach of aseptic fluid collection, culture was not performed. In consideration of the fluid cytology and likelihood of a complete congenitally originating nonperforate hymen, the fluid was most likely sterile. The mild anemia and hyperfibrinogenemia were most likely associated with chronic inflammation due to low-grade uterine disease and/or inflammation subsequent to tenesmus and rectal prolapse. Ceftiofur sodium (Pfizer, New York, New York, USA) 2.2 mg/kg SC, q12h and flunixin meglumine (Schering-Plough Animal Health, Union, New Jersey, USA) 1 mg/kg IM q24h were administered as prophylaxis for ascending infection. Oxytocin (IVX Animal Health, St. Joseph, Missouri, USA), 10 IU IM q6h was also administered to encourage evacuation of the uterus.

Figure 2.

Appearance of fluid drained from the uterus in the alpaca (case 1) after perforation of the hymen.

The following day, repeat ultrasonography revealed the persistence of fluid-filled uterine loops that were markedly reduced in size (< 80% of original measurement). The tenesmus ceased and normal posturing to urinate and defecate was noted. The alpaca was sedated, using the same protocol as on the previous day, and the persistent hymen was dilated by introducing well-lubricated sterile cylindrical instruments of increasing diameters. These were a 35-mL syringe casing (27-mm diameter), a cardboard mare speculum (33-mm diameter), and a glass mare speculum (38-mm diameter). Each instrument was inserted slowly without direct visualization of the hymen. Manual sensitivity of the operator and prior measurement of the depth of the hymen from the vaginal opening were used to guide passage of the instrument past the level of the persistent hymen. Each instrument was left in position past the site of obstruction for 30 s before introduction of the next instrument. The maximal dilation diameter of 38 mm was chosen based on available instrument size and judgment of the authors on an acceptable vaginal diameter. An additional 2 L of fluid was drained from the uterus. A 5 L volume of a sterile polyionic solution (Normosol, Lake Forrest, Illinois, USA) was used to lavage the uterus. Medications were continued as described previously. Repeat ultrasound the following day revealed minimal fluid within the uterus. Uterine lavage was repeated and the alpaca was discharged from hospital with ceftiofur sodium for 7 d and oxytocin for 5 d.

Recheck examination by the referring veterinarian 7 d after discharge revealed re-formation of a fibrinous membrane in the area of the hymen. Bacterial culture of a uterine swab revealed scant growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae and the alpaca was referred for re-evaluation. Physical examination at re-admission was unremarkable. Hematology and serum chemistry were within normal limits except for the persistence of the mild anemia (hematocrit 24.6%). Ultrasonography revealed a moderately dilated uterus filled with hyperechoic fluid (grade 1 out of 4). Endoscopy revealed that a non-perforate fibrinous membrane had re-formed in the region of the hymen. Repeat perforation and dilation of the membrane was performed as previously described. The endometrium appeared to be markedly hyperemic and irregular. Cytological features of a uterine fluid sample were similar to those of the prior visit and bacterial culture was negative. Antibiotic therapy was changed to florfenicol (Schering-Plough Animal Health), 20 mg/kg SC q24h, and flunixin meglumine (Schering-Plough Animal Health), 1 mg/kg IM q24h, was administered for 7 d. Uterine lavage was performed with a total of 5 L of isotonic saline q24h for 5 d and a 14F inflated foley catheter (4.62 mm diameter, 30 mL cuff volume) was placed in the vestibule where the remnant of the hymen was, just outside the cervix. During each daily uterine lavage, the fluid initially contained blood clots, but gradually it became clear with subsequent fluid boluses.

Endoscopy was performed on day 7 after re-admission. The hymen had fibrosed, leaving an opening of 10 mm in diameter. The uterine wall was less hyperemic, suggesting receding inflammation. A small amount of red-brown fluid was present in the uterine horns; bacterial culture of this fluid was negative. The uterus was lavaged with saline and 1 g of ceftiofur sodium dissolved in 20 mL of sterile water was deposited into the uterus post lavage.

Laser ablation of the persistent hymen, repeat endoscopy and uterine biopsy following resolution of uterine inflammation were discussed with the owners. Due to the possibility of cicatrix formation and subsequent dystocia secondary to further intervention, the owners elected to retire the animal from breeding. The alpaca was given to a new owner as a pet and has not been reported to have had any vaginal discharge or associated systemic abnormalities. No further diagnostic procedures have been performed since discharge from hospital.

Case 2

An 18-month-old llama was presented for reproductive evaluation. She had a history of being bred 3 times prior to examination, with the male apparently having difficulty positioning himself at each mating. This was described by the owners as the relatively more caudal position of the male over the female’s dorsum during intromission. As the mating attempt progressed, the female appeared to become progressively more uncomfortable and had a tendency to lie in lateral recumbency. Physical examination at presentation was unremarkable. Rectal examination revealed a fluid-filled viscus consistent with the uterus. Transabdominal and transrectal ultrasound (Figure 3) confirmed the presence of a fluid-filled (grade 1 out of 4) structure consistent in appearance with the uterus.

Figure 3.

Transrectal ultrasonographic appearance of fluid-filled uterus in the llama (case 2), with the bladder (1) and uterus (2) demonstrated. Each hatched line of the left of the image represents 1 cm.

An imperforate membrane was identified in the caudal aspect of the vestibule during endoscopy of the vagina (Figure 4) which prevented visualization of the cervix and vagina. A diagnosis of persistent hymen and mucometra was made. Rupture and manual dilation of the hymen remnants was performed using the technique described in case 1 and approximately 1 L of opaque white fluid was drained from the uterus. In the absence of clinical signs of infectious disease, cytology and culture were not performed. The llama was given prophylactic antimicrobials (ceftiofur sodium 4.4 mg/kg IM q12h, 7 d) and flunixin meglumine (0.5 mg/kg IM q12h, 3 d). Recheck ultrasound examination was recommended in 2 wk with attempts at re-breeding to be delayed for 4 mo to allow the endometrium to heal and to coincide with spring breeding.

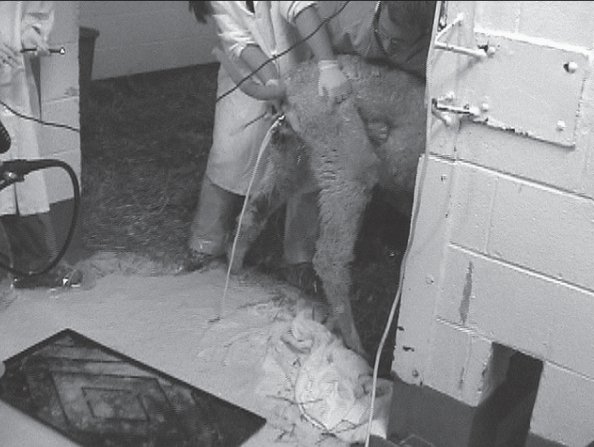

Figure 4.

Videoendoscopic appearance of the persistent hymen (1) in the llama (case 2).

Repeat examination after 2 wk was not performed, but examination prior to re-breeding 4 mo after treatment revealed no abnormalities. A single breeding was performed without incident after this examination. Three months later, a positive pregnancy diagnosis by ultrasound examination was made. Repeat ultrasound examination 1 and 3 mo after initial pregnancy diagnosis detected a live fetus, and the llama subsequently delivered a healthy cria without dystocia.

Discussion

The hymen is formed from the epithelial lining of the paramesonephric ducts and the urogenital sinus at the vestibulovaginal junction (3). Canalization of the hymen is usually complete at birth and leads to communication between the lumen of the caudal vagina and vestibule (3). Persistent or imperforate hymen has been described in camelids, but heredity has not been established (4). A common combination of congenital defects in alpacas and llamas of suspected polygenic recessive traits is wry face and choanal atresia (5). In these instances, suspected heredity is associated with increased occurrence in South American versus Old World camelids and increased incidence in related animals (5). In both these cases, the owners were not aware of any prior incidence of persistent hymen in related animals. Due to the perceived low incidence of persistent hymenal membranes and lack of history of affected relatives, heritability is most likely low.

The lack of communication between the vulva and vagina is a form of segmental aplasia that may co-exist with other congenital defects in South American camelids (6). In both these cases, no other abnormalities were identified, although necropsy examination was not performed. Congenital deformities of the reproductive tract of camelids are rare and in a prior case series of 6 alpacas, congenital vulva deformity was reported to be associated with a totally to subtotally imperforate vulva (7). Two of these 6 animals did develop secondary urometra, but surgical intervention to resolve the vulva deformity was immediate and long-term associations with infertility were not reported (7). In another report, labial fusion as a cause of urinary tract obstruction in an alpaca cria was not associated with urometra (8).

In cattle, the most common developmental aberration of the female reproductive tract is a variable degree of hymen persistence (9). The most commonly affected breed is the white shorthorn, considered due to a sex-linked recessive gene (9). Accumulation of secretions has been associated with complete hymen obstruction, which can be relieved by trocar and cannula (9). Surgical intervention to enable successful breeding is not advisable due to the probably hereditary origin (9). In other ruminant species and the horse, persistent hymen is reported, but heritability is unknown.

Surgical treatment of persistent hymen membrane and vestibulovaginal narrowing/obstruction has been reported in dogs (10–13), in which the sequelae include hydrocolpos, uterine fluid accumulation, and urinary incontinence. Hydrocolpos is a rare congenital disorder in dogs, in which obstruction of the vagina (colpos) causes accumulation of secreta from the uterus and vagina, resulting in distension of the vagina (13). Treatment has included manual dilation, T-shaped vaginoplasty, vaginectomy, and resection of the stenotic area (12,13). Manual dilation in dogs has had disappointing results with stricture formation a common sequela (12–14). In the alpaca described in case 1, repeated manual dilation was unsuccessful, in stark contrast to the success achieved in the llama of case 2. This difference may have been associated with the smaller size of the alpaca, differences in extent of persistent hymen membrane or species differences. Increased case numbers and treatments are required to evaluate potential factors that may influence outcome in South American camelids.

In dogs, vaginal resection and anastomosis of the caudal vagina and vestibule through an episiotomy or vaginectomy with concurrent hysterectomy appear to be the preferred surgical options (12,13). A caudal laparotomy approach to segmental resection and anastomosis of the vagina has also been reported in dogs (15). The use of vaginectomy and hysterectomy in alpacas and llamas may be limited to those owners who do not require their animals for reproductive performance post surgery.

Imperforate hymen membranes also occur in humans, in whom treatment with carbon dioxide laser under local anesthesia has been used (16,17). In these cases, recovery was unremarkable. Corrective surgery is also commonly performed using a central oval incision to perforate the hymenal membrane followed by introduction of a 16F Foley catheter and balloon insufflation (18). The catheter is left in place for 2 wk and estrogen cream (Premarin Vagina Cream; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) is applied to the hymenal structure for an additional 2 wk. This cream has a mixture of sodium estrone sulfate and sodium equilin sulfate at a concentration of 0.625 mg/g. There are also smaller amounts of concomitant components, such as sodium sulfate conjugates, 17 α-dihydroequilin, 17 α-estradiol, and 17 β-dihydroequilin. In a case series of 65 women, closure of the hymenal orifice occurred in only 2 women following this procedure, which was believed to be related to inappropriate administration of estrogen cream (18).

Tissue repair, integrity, and remodeling may be influenced by estrogen, which accelerates cutaneous wound healing processes by enhanced matrix deposition, rapid epithelialization, and damping of the inflammatory response (19). Estrogen also has a role in regulating macrophage inhibition factor (MIF), a proinflammatory cytokine, expression at days 3–7 after wounding (20). Estrogen is also known to influence the hormone relaxin, which mediates deposition of collagen (21). Thus, increased estrogen levels increase relaxin, which in turn decreases deposition of collagen and potentially decreases adhesions (22). Topical estrogen, therefore, has become the mainstay of treatment for humans with labial fusion and has great potential for animal applications (22).

The duration and volume of fluid accumulation in case 1 could have affected the endometrium via pressure atrophy. Uterine biopsy without complications has been described in llamas, and was valuable in identifying a wide range of uterine diseases (23). This would have been useful in both these cases to assess whether further restriction from breeding was required to resolve persistent inflammation or characterize endometrial disease and assist in determining the prognosis for reproductive soundness. Another author, however, has cautioned that uterine biopsy should only be performed if concurrent rectal manipulation is possible, due to the inherent risk of uterine perforation (24). In case 1, uterine biopsy was recommended but declined by the owners.

The purpose of this case report was to document the technique of instrument-assisted manual dilation of persistent hymen. Despite initial success, some cases of hymenal persistence in camelids may not resolve. The daily application of estrogen creams should be considered to improve success rates, but surgery or laser treatment may be required. There is currently not enough information available to suggest that hymen persistence is hereditary, but veterinarians and owners should be aware of this possibility, and the occurrence of concurrent congenital defects.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Dr. Tan wrote the manuscript, was the resident on cases, and revised the manuscript as per the reviewer comments.

Dr. Dascanio was the primary clinician on cases, and revised and edited the manuscript for Dr. Tan after initial write-up.

References

- 1.Schumacher J. Diseases of the rectum. In: Mair T, Divers TJ, Ducharme NG, editors. Manual of Equine Gastroenterology. London, NY: Saunders; 2001. pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinnon AO, Squires EL, Pickett BW. Equine Reproductive Ultrasonography. Fort Collins CO: Colorado State University, Animal Reproduction Laboratory; 1988. Uterine pathology; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts SJ. Veterinary Obstetrics and Genital Diseases. 3. New York: David & Charles; 1986. Female gential anatomy and embryology; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler ME. Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids: Llama, Alpaca, Vicuna, Guanaco. 2. Ames, IA: Iowa State Univ. Press; 1998. Surgery; pp. 108–147. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson LW. An overview of camelid congenital/genetic conditions. International camelid health conference for veterinarians. 2008:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bravo PW. The Reproductive Process of South American Camelids. Salt Lake City, UT: Seagull Printing; 2002. Abnormalities of reproduction in lamoids; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkins PA, Southwood LL, Bedenice D. Congenital vulvar deformity in 6 alpacas. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;229:263–265. doi: 10.2460/javma.229.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallowell GD, Potter TJ, Mills NJ. Labial fusion causing urinary tract obstruction in an alpaca cria. Vet Rec. 2007;161:862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkinson TJ. Infertility in the cow: Structural and functional abnormalities, management and non-specific infection. In: Noakes DE, Parkinson TJ, England GCW, editors. Arthur’s Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics. 8. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001. pp. 383–472. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somers S. Case of a persistent hymen. Vet Rec. 1991;128:288. doi: 10.1136/vr.128.12.288-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsumagari S, Takagi K, Takeishi M, et al. A case of a bitch with imperforate hymen and hydrocolpos. J Vet Med Sci. 2001;63:475–477. doi: 10.1292/jvms.63.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyles AE, Vaden S, Hardie EM, et al. Vestibulovaginal stenosis in dogs: 18 cases (1987–1995) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;209:1889–1893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viehoff FW, Sjollema BE. Hydrocolpos in dogs: Surgical treatment in two cases. J Small Anim Pract. 2003;44:404–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2003.tb00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holt PE, Sayle B. Congenital vestibulo-vaginal stenosis in the bitch. J Small Anim Pract. 1981;22:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1981.tb01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gee BR, Pharr JW, Furneaux RW. Segmental aplasia of the Müllerian duct system in a dog. Can Vet J. 1977;10:281–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman M, Gal D, Peretz BA. Management of imperforate hymen with the carbon dioxide laser. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:270–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu TJ, Lin MC. Acute urinary retention in two patients with imperforate hymen. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1993;27:543–544. doi: 10.3109/00365599309182293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acar A, Balci O, Karatayli R, et al. The treatment of 65 women with imperforate hymen by a central incision and application of Foley catheter. BJOG. 2007;114:1376–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pirila E, Parikka M, Ramamurthy NS, et al. Chemically modified tetracycline (CMT-8) and estrogen promote wound healing in ovariectomized rats: Effects on matrix metalloproteinase-2, membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase, and laminin-5 γ2-chain. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10:38–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2002.10605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashcroft GS, Mills SJ, Lei K, et al. Estrogen modulates cutaneous wound healing by downregulating macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1309–1318. doi: 10.1172/JCI16288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherwood OD. Relaxin’s physiological roles and other diverse actions. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:205–234. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schober J, Dulabon L, Martin-Alguacil N, et al. Significance of topical estrogens to labial fusion and vaginal introital integrity. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:337–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powers BE, Johnson LW, Linton LB, et al. Endometrial biopsy technique and uterine pathologic findings in llamas. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;197:1157–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purdy SR. Camelid medicine, surgery and reproduction for veterinarians. Ohio State University: Ohio State University; 2002. Female camelid breeding soundness examination; pp. 347–351. [Google Scholar]