Abstract

The objective of this study was to evaluate a commercial blood test (DG29) for pregnancy in cattle. Compared with ultrasound, the sensitivity of the assay for detecting pregnancy around day 30 post-insemination was 99.4% [95% confidence interval (CI): 96.1–100]. The specificity was 100% (95% CI: 84.7–100) in noninseminated cattle, and 66.7%; (95% CI: 49.7–80.4) in inseminated nonpregnant cattle. Positive and negative predictive values were 92.6% and 96.3%, respectively, in a sample of inseminated cattle in which 80% were pregnant.

Résumé

Évaluation du test DG29 pour la détection précoce de la gestation chez le bovin. L’objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer un test de gestation commercial (DG29) chez les bovins. En comparaison avec le diagnostic échographique, la sensibilité du test autour du jour 30 post-insémination est de 99,4 % (95 % IC: 96,1–100). La spécificité était de 100 % (95 % IC: 84,7–100) chez les animaux non-inséminés, et 66,7 % (95 % IC: 49,7–80,4) chez les bovins inséminés nongestants. Les valeurs prédictives positives et négatives étaient de 92,6 et 96,3 %, respectivement, dans un échantillon de bovins dont 80 % étaient gestants.

(Traduit par les auteurs)

The dairy and the beef industry both benefit from knowing the pregnancy status of the animals in a herd. The ability to identify open cows quickly and re-inseminate them as soon as possible, allows producers to increase their profitability (1). Therefore, the frequency and accuracy of pregnancy diagnosis methods have a direct impact on cattle management (2). Traditionally, producers have relied on veterinarians to palpate cows after 35 d of gestation or use ultrasound after day 28 (2,3). The accuracy of these conventional methods depends on the practitioner’s experience, the gestational stage, the age of the animal and its body condition score (4). While these techniques have served the producers well over the years, they all require that a veterinarian visit the farm.

Researchers and businesses have invested in the creation of alternative and/or complementary methods to traditional pregnancy diagnoses, targeting an increased availability and frequency of pregnancy testing. From those early endeavors, on-farm tests were developed, mostly based on detecting progesterone (P4) or an early conception factor (ECF) in milk or blood, methods that appeared promising at one time. However, P4 and ECF tests were less accurate than traditional rectal palpation (4,5). Other methods such as detection of specific placental proteins by laboratory analysis appeared promising as a complement to the conventional methods (6,7). To date, multiple placental proteins have been identified, with more than 20 cDNA segments encoding them (8). By using a pregnancy test between veterinary visits, producers may be able to know the pregnancy status of their animals and respond promptly if needed. The objective of this study was to evaluate the performance of the DG29 pregnancy test, based on the presence of a protein linked to pregnancy. The DG29 test is a laboratory enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) type test that measures the level of a specific protein in blood that is linked to pregnancy (confidential corporate information, Conception, 392 chemin du Fleuve, Beaumont, Québec).

Data were used that came from a study originally conducted by the Centre de Recherche en Biologie de la Reproduction (CRBR, Laval University) between September 2000 and December 2002. First-calf heifers were placed into 2 groups: noninseminated (18 heifers), and inseminated [by artificial insemination (AI) or embryo transfer (ET)]. Blood samples were taken at D7 (days 5 to 9), D14 (days 12 to 16), D21 (days 17 to 23), D30 (days 29 to 36), and D60 (days 44 to 66) post-insemination and ultrasonogrpahy was performed at the time of the D30 sampling. A total of 1517 blood samples were subjected to the DG29 test. Heifers observed to be nonpregnant (based on presence of signs of heat) prior to D30 were re-inseminated and sampling was discontinued. Because the original database included multiple occurrences of the same animal, heifers that were included repeatedly in the study were selected at random. Data were evaluated from 202 unique cattle that had been diagnosed as pregnant using ultrasound. Test results (DG29) at D30 post-insemination were used to estimate test sensitivity and specificity, relative to ultrasound pregnancy diagnosis at D30. Positive and negative predictive values were computed using cattle that were inseminated (conception rate 80.7%). This very high conception rate was elevated artificially as a result of the exclusion of animals that came into heat before D30; these animals were re-inseminated and therefore not sampled past D21.

In the DG29 test, a standard curve is used to measure the quantity of test target protein and results are expressed as seropositive or seronegative based on a 500 pg/mL cut-off. The manufacturer recommends that DG29 be used from 29 d after breeding and 100 d, or more, after calving to avoid false positives resulting from the high amount of the protein at calving. Inter-assay variability of the test was assessed by testing 10 samples (standards and controls) on different lots and different plates. Intra-assay variability was assessed by testing 6 samples (3 from nonpregnant animals and 3 from pregnant ones) 6 times on the same plate. Sensitivity (the probability that an animal classified as pregnant by ultrasound at D30 was classified as pregnant by the DG29 test) and specificity (the probability that an animal classified as nonpregnant by ultrasound at D30 was classified as nonpregnant by the DG29 test) were estimated for samples taken on or after 29 d post-insemination, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed (9). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean test target protein quantity at D7, D14, D21, D30, and D60 in pregnant cattle.

In this study, over 95% of the blood samples tested at D7 (196/198), D14 (197/201), and D21 (187/197) were seronegative according to DG29. Nine of the 10 samples seropositive to DG29 at D21 for the inseminated group were confirmed as being pregnant at D30 by DG29 and by ultrasound. The specificity in noninseminated cattle was 100% (18/18, 95% CI: 84.7–100).

The DG29 results at or after 29 d post-insemination are summarized in Table 1. Blood samples were taken on average at day 32 post-insemination (standard deviation (s) = 1.5; minimum = 29; maximum = 36). The specificity in nonpregnant animals was lower than that in noninseminated animals (26/39, 66.7%; 95% CI: 49.7–80.4). The sensitivity of the assay for cattle between days 29 and 36 post-insemination was 99.4% (162/163; 95% CI: 96.1–100). The only pregnant heifer examined using ultasound that was classified as nonpregnant by DG29, was seropositive at day 14, but seronegative at days 20, 29, and 59, and was recorded by the veterinarian as having had an embryonic mortality at day 60. Considering only inseminated cattle (conception rate of 80.7%), the positive and negative predictive values for DG29 were 92.6% and 96.3%, respectively.

Table 1.

Distribution of DG29 results between days 29 and 36 post-insemination for cattle that were pregnant or nonpregnant as determined by ultrasonographic examination at D30

| Number of cattle inseminated (artificial insemination or embryo transfer)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant by ultrasound | Nonpregnant by Ultrasound | |

| Pregnant by DG29 | 162 | 13 |

| Nonpregnant by DG29 | 0 | 27* |

| Total | 162 | 40 |

Based on DG29 results between days 29 and 36, one heifer that had been classified as pregnant at day 14, but nonpregnant at days 20, 29, and 59 and was recorded by the veterinarian as having had an embryonic mortality at day 60, was included in this group.

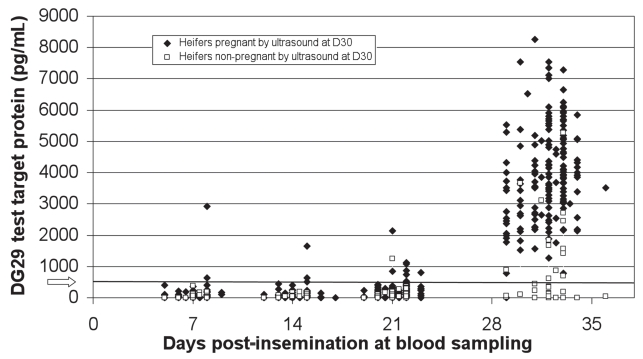

Figure 1 illustrates the DG29 test target protein levels at D7, D14, D21, and D30 in cattle that were determined to be pregnant or nonpregnant by ultrasound at D30. Mean test target protein level in noninseminated cattle was 15 pg/mL and was consistently less than 140 pg/mL. Mean test target protein levels at D7, D14, D21, D30, and D60 post-breeding in pregnant cattle were 67, 81, 179, 3904, and 5087 pg/mL, respectively. A significant difference in the quantity of pregnancy protein in the blood was identified by ANOVA between D21 and D30, and between D30 and D60 in pregnant animals (P < 0.0001). Mean test target protein levels at D7, D14, D21, and D30 post-breeding in nonpregnant inseminated cattle were 49, 39, 100, and 747 pg/mL, respectively; 13/39 animals classified as non-pregnant by ultrasound were classified as pregnant by DG29 at D30. All seropositive nonpregnant animals had less than 200 pg/mL of the target protein at D7 and D14 samplings.

Figure 1.

DG29 test target protein at D7, D14, D21, and D30 post-insemination for cattle determined to be pregnant (n = 163) or nonpregnant (n = 39) by ultrasound at D30.

In inter-plate assays, the coefficients of variation (CV) of the optical densities (ODs) had a median of 8% with a range of 5% to 15%. In intra-plate assays, the CV of the ODs for seropositive and seronegative samples varied from 2% to 3% and from 3 to 5%, respectively.

The results presented suggest that the protein detected by DG29 is present at a relatively early stage, but the test cannot be used before day 29 to detect nonpregnant animals. When the test is performed between day 29 and day 36 of gestation, the estimated sensitivity for detecting pregnancy is excellent (99.4%).

Animals classified as being pregnant according to their DG29 test result, but diagnosed as being nonpregnant at D30 by ultrasound, may have had false positive results due to: 1) protein residue detected by DG29 from embryo mortality; and/or 2) misclassification by ultrasound or by DG29 at D30. In cattle, carryover protein from a previous pregnancy may produce false seropositive results if the 100-days-from-calving delay is not observed. The fact that specificity was excellent in noninseminated animals suggests early embryonic death was the cause of less than perfect specificity in inseminated animals.

The negative predictive value of 96.3% was excellent, in this artificial context of a conception rate greater than 80%. Reported conception rates of 35% to 45% (10) caution interpretation of this negative predictive value. However, adding nonpregnant animals to Table 1 may decrease the positive predictive value but may only increase the negative predictive value of the test. Moreover, between 30 and 60 d post-insemination, there was a significant increase in test target protein in pregnant cattle, suggesting that the test sensitivity may increase with time between 30 and 60 days post-insemination.

The high efficiency of estrus detection observed in this study was likely due to the exclusive use of heifers in this trial, and to a highly controlled environment that included above average management, use of estrus synchronization, and free stall housing. There would be value in performing a new study in which nonpregnant animals were tested at D30 to estimate the specificity of the DG29 test in a situation in which estrus detection efficiency is lower than that of the present study; and reflective of a typical situation. External validity of this evaluation may also be enhanced in future by including cows in their 2nd or later pregnancy in such a study.

The DG29 may complement owners’ observations and the veterinarian’s services of rectal palpation and ultrasound. This tool might identify early embryo mortality that is not normally detectable by traditional pregnancy methods of diagnosis. cvj

References

- 1.De Vries A. Economic value of pregnancy in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2006;89:3876–3885. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filteau V, DesCôteaux L. Valeur prédictive de l’utilisation de l’appareil échographique pour le diagnostic précoce de la gestation chez la vache laitière. Med Vet Québec. 1999;28:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romano JE, Thompson JA, Forrest DW, Westhusin ME, Tomaszweski MA, Kraemer DC. Early pregnancy diagnosis by transrectal ultrasonography in dairy cattle. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1034–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2006.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youngquist RC. Pregnancy diagnosis. In: Youngquist RC, Threlfall WR, editors. Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology. 2. St-Louis: Saunders; 2007. pp. 294–303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrose DJ, Radke B, Pitney PA, Goonewardene LA. Evaluation of early conception factor lateral flow test to determine nonpregnancy in dairy cattle. Can Vet J. 2007;48:831–835. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasser RG, Ruder CA, Ivani KA, Butler JE, Hamilton WC. Detection of pregnancy by radioimmunoassay of a novel pregnancy-specific protein in serum of cows and a profile of serum concentrations during gestation. Biol Reprod. 1986;35:936–942. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.4.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zoli AP, Guilbault LA, Delahaut P, Ortiz WB, Beckers JF. Radioimmunoassay of a bovine pregnancy-associated glycoprotein in serum: Its application for pregnancy diagnosis. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:83–92. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green JA, Xie S, Quan X, et al. Pregnancy-associated bovine and ovine glycoproteins exhibit spatially and temporally distinct expression patterns during pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1624–1631. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryhn H. Veterinary Epidemiologic Research. Charlottetown: AVC Inc; 2003. Screening and diagnostic tests; pp. 85–120. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos JEP, Thatcher WW, Chebel RC, et al. The effect of embryonic death rates in cattle on the efficacy of estrus synchronisation programs. Ani Reprod Sci. 2004;82–83:515–535. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]