Dealing with veterinary oncology cases is often a great challenge for veterinarians. Not only does the wide range of presenting signs and cancer types require a veterinarian to be constantly vigilant, but also the high prevalence rates of some cancers mean that the battle against cancer in pets is seemingly constant. Vetnosis, an independent research and consulting firm, which specializes in animal health, recently published Oncology Insight, the first in-depth, international study of current and future prospects for the veterinary oncology sector in pets. As part of this study, Vetnosis surveyed 404 first opinion veterinarians (171 in the United States, 75 in the United Kingdom, 83 in France, and 75 in Germany). In addition, Vetnosis carried out in-depth interviews with 16 first opinion veterinarians and 15 veterinary oncology specialists about the daily challenges they face in diagnosing and treating pet cancers. This article highlights some of the interesting insights that were contributed.

Cancer prevalence

Whilst the prevalence rates for different types of cancer vary, it has been estimated that as many as 1 in 4 dogs and 1 in 6 cats will develop cancer at some time in their life (1). It has also been reported that almost 50% of dogs over the age of 10 y will die of cancer-related problems (1). There is no doubting the importance of oncology in companion animal practice in terms of case throughput. As pet health care becomes more and more developed, pets are living longer lives. As geriatric pets represent a growing proportion of the pet population, this is bound to have an impact on the volume of pet cancer cases.

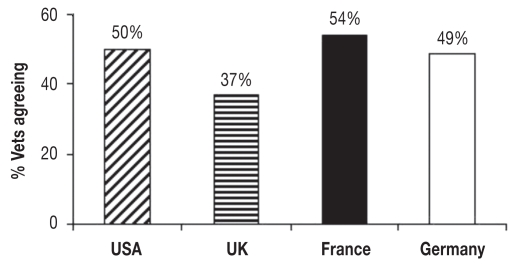

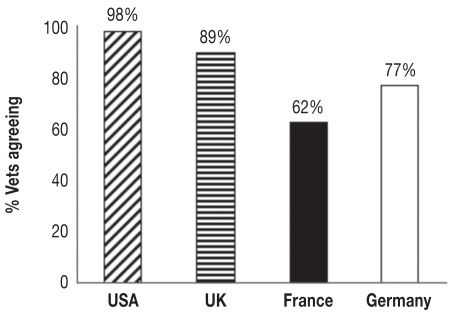

A significant number of the veterinarians involved in Oncology Insight reported that they are seeing cancers in pets more and more frequently. About 50% of veterinarians surveyed from the US, France, and Germany felt that this was the case, with a lower percentage of veterinarians in the UK agreeing with this assertion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Veterinarians who agreed with the statement “I am seeing cancer in dogs more and more frequently.” Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Cancer recognition and diagnosis

The recognition by owners of signs in their pet, which may reflect the presence of cancer, is one area that most challenges veterinarians dealing with oncology cases. Owners who do not recognize signs of illness in their pet, or do not realize the potential significance of such signs, often present their pet for diagnosis at a stage which is too late to allow for optimal case management.

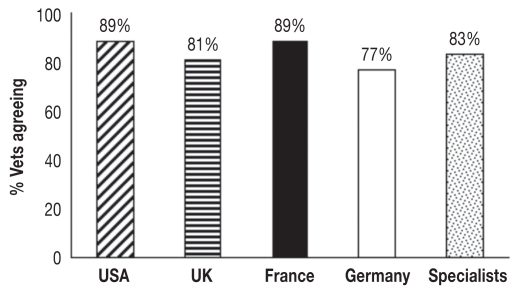

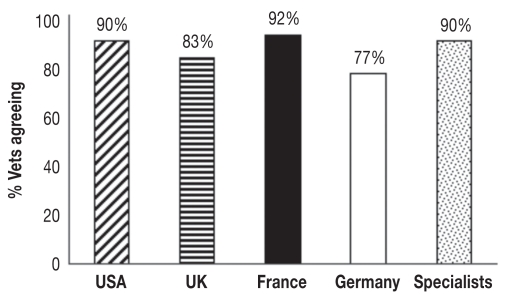

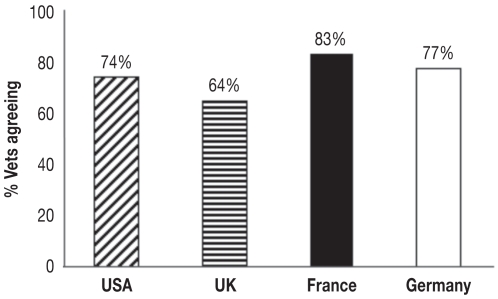

Most veterinarians surveyed for Oncology Insight indicated that the recognition of cancer at an advanced stage of disease often prevented optimal case management (Figures 2 and 3). This is unlikely to be of any great surprise to other veterinarians who carry out regular companion animal consultations; however, it does highlight an important area where investment of resources could potentially offer high welfare rewards. Education of pet owners on the typical signs of cancer, for which they should be vigilant, may encourage earlier case presentation. Once a case has been presented to the veterinarian, Oncology Insight uncovered that the situation starts to look much more positive. Most veterinarians surveyed indicated that they pursue a definitive (histopathological) diagnosis in the vast majority of canine and feline cancer cases that they see (Figure 4). This high percentage of veterinarians seeking a definitive diagnosis for cancer cases is likely to reflect advancements in the understanding of oncology through the development of veterinary oncology as a specialty, an increased focus on oncology within veterinary universities, and the increasing availability of high quality continuing education courses. This is bodes well for the continued growth of understanding and awareness of pet cancers.

Figure 2.

Veterinarians who agreed with the statement “The recognition of cancer at an advanced stage of disease progression reduces the potential for optimal disease management in a large proportion of dogs.” Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Figure 3.

Veterinarians who agreed with the statement “The recognition of cancer at an advanced stage of disease progression reduces the potential for optimal disease management in a large proportion of cats.” Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Figure 4.

Veterinarians who agreed with the statement “I pursue a definitive diagnosis in the vast majority of canine/feline cancer cases that I see (for example, histopathology)”. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Cancer case referral

Most of the veterinarians surveyed referred pet cancer cases to some degree (Figure 5). The referral culture is somewhat more developed in the US and UK, but as veterinary oncology grows as a specialty, the referral of cases within France and Germany is likely to increase.

Figure 5.

Veterinarians who indicated that they have referred cases to a veterinary oncologist. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

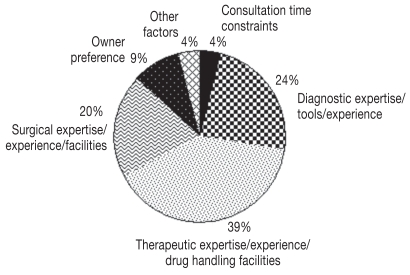

The factors that affect a veterinarian’s decision to refer a case are complex; however, therapeutic expertise, experience, or drug handling facilities proved to be the most important (Figure 6). Diagnostic experience, expertise or tools and surgical experience, expertise or facilities are also major factors which drive the referral of cancer cases to veterinary oncology specialists.

Figure 6.

Relative importance of different factors that may affect a veterinarian’s decision to refer a cancer case. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Cancer case management

Having overcome the hurdles of cancer recognition and diagnosis, the field of cancer management offers yet more challenges to the veterinarian. Many treatment modalities are available to treat cancers in pets, some of which require significant investment in expensive technology and robust precautions to ensure user safety. The very nature of cancer therapeutics, the need to kill living cells within the body, means that achieving optimal therapy without side effects can be very challenging. In veterinary medicine a balance has been reached, whereby the welfare of the patient is not compromised in order to achieve a more positive clinical outcome. The end result is that whilst therapy is often palliative, it is generally possible for pets to have a good quality of life throughout therapy and during any remission phase.

This is another area that was highlighted as critical for effective owner education. Many owners are affected by their own experience of cancer or that of a friend or family member. They may have had particularly bad experiences of some of the treatment side effects seen in human patients, where a cure is often sought even though the patient’s short-term quality of life may be significantly compromised. These preconceptions may have a negative effect on an owner’s willingness to pursue cancer therapies for their pet. Veterinarians highlighted the importance of discussing the differences between human cancer therapeutic strategies and those utilized in veterinary medicine. In addition to educating the owner, some specialists remarked on the importance of the language that is used when speaking with them. In particular the words “cancer” and “chemotherapy” may carry intensely negative connotations for many owners.

Therapeutic advances and chemotherapy drug usage

In recent years the management of cancers in pets has seen advancements which have generally been driven by developments in human oncology. Advancements in delivery of radiotherapy, chemotherapeutic protocols and drug delivery, immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy all offer great promise for the future of veterinary oncology. The arrival of the first conditionally licensed vaccine against malignant melanoma in dogs in the United States signified 2007 as an important year for the oncology therapy area (2).

Dogs provide good models for some human cancers, and are increasingly being studied in the development of novel human cancer therapeutics (3). Although some new technologies may not be transferable to veterinary species due to species specificity, it is likely that the study of canine and feline cancers will bring mutual benefit to human and veterinary patients in the future.

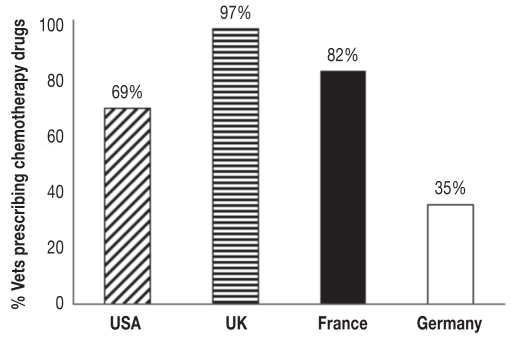

Despite these advancements, however, there are still no chemotherapeutic products with a veterinary license to treat cancers in pets. The use of human generic chemotherapeutic drugs to treat veterinary cancers is widespread, with many veterinarians indicating that they use these products within their clinic (Figure 7). Chemotherapeutic drug use was lower in Germany than in the US, the UK, and France.

Figure 7.

Veterinarians who indicated that they use chemotherapy drugs in their clinic. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

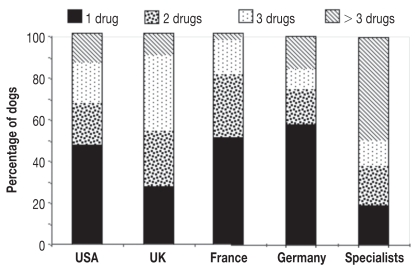

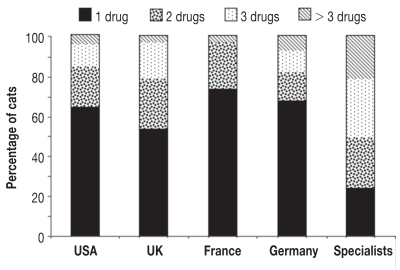

Amongst veterinary specialists, multi-drug chemotherapeutic protocols were commonly used in both dogs and cats (Figures 8 and 9). In general, first opinion veterinarians tended to use multi-drug protocols less commonly; however, significant numbers of first opinion veterinarians reported using protocols utilizing 2 or more drugs in dogs. First opinion veterinarians used multi-drug protocols less commonly in cats. Veterinary oncology specialists utilized multi-drug protocols at a similar frequency in cats and dogs.

Figure 8.

Percentage of canine oncology cases receiving protocols that contain 1, 2, 3 or >3 chemotherapeutic drugs. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Figure 9.

Percentage of feline oncology cases receiving protocols that contain 1, 2, 3, or >3 chemotherapeutic drugs. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

Veterinary satisfaction

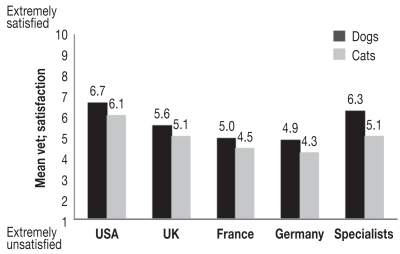

Veterinarians face the challenge of diagnosing and managing pet cancers largely without licensed veterinary therapeutics. Many veterinarians report that they are seeing cancers more and more frequently, and yet some indicated that they still do not have adequate access to cancer therapy referral facilities, such as radiotherapy units. Veterinarians indicated that they are not highly satisfied with cancer management options, and that their satisfaction is lower with feline cancer management options than with canine cancer management options (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Veterinarian satisfaction with cancer management options. Source: Oncology Insight. Vetnosis, February, 2008.

It is clear that pet cancers are going to remain a significant problem facing pets, their owners, and veterinarians; however, huge advancements have been made in the understanding of pet cancers and their treatment. First opinion veterinarians are offering more and more to their clients in terms of cancer management options as well as education and support. Despite this, there are still significant areas of need within veterinary oncology that should be met. It is hoped that the findings of Oncology Insight will aid the animal health industry in focusing on the advancement of pet cancer management in the future.

Acknowledgments

Vetnosis thanks all of the first opinion veterinarians and veterinary oncology specialists who kindly contributed to Oncology Insight. Any veterinarians who would like to participate in future Vetnosis studies may contact the author. e-mail: camilla.kidd@vetnosis.com.

References

- 1.European Society of Veterinary Oncology. [Last accessed October 2, 2008];Information for Pet Owners. [page on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.esvonc.org/PetownerbrnbspnbspInformation/tabid/54/Default.aspx.

- 2. [Last accessed October 2, 2008];USDA Grants Conditional Approval for First Therapeutic Vaccine to Treat Dog Cancer. Posted 26/03/2007. [page on Internet] Available from: http://www.emaxhealth.com/117/10535.html.

- 3.Porrello A, Cardelli P, Spugnini EP. Oncology of companion animals as a model for humans. An overview of tumor histotypes. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2006;25:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]