Abstract

Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) is a heterodimeric, nitric oxide (NO)-sensing hemoprotein composed of two subunits, α1 and β1. NO binds to the heme cofactor in the β1 subunit, forming a 5-coordinate NO complex that activates the enzyme several hundred-fold. In this report the heme domain has been localized to the N-terminal 194 residues of the β1 subunit. This fragment represents the smallest construct of the β1 subunit that retains the ligand binding characteristics of the native enzyme, namely tight affinity for NO and no observable binding of O2. A functional heme domain from the rat β2 subunit has been localized to the first 217 amino acids β2(1-217). These proteins are ∼40% identical to the rat β1 heme domain, form 5-coordinate, low-spin NO complexes and 6-coordinate, low-spin CO complexes. Like sGC these constructs have a weak Fe-His stretch (208 and 207 cm−1 for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively). β2(1-217) forms a CO complex that is very similar to sGCand has a high ν(CO) stretching frequency at 1994 cm−1. The autoxidation rate of β1(1-194) was 0.073 per minute, while the β2(1-217) was substantially more stable in the ferrous form with an autoxidation rate of 0.003 per minute at 37 °C. This report has identified and characterized the minimum functional ligand binding heme domain derived from sGC providing key details towards a comprehensive characterization.

Soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC1) is a well-characterized NO-sensor, containing a heme-bound, N-terminal domain that binds NO, regulating a C-terminal guanylate cyclase. sGC catalyzes the conversion of GTP to cGMP, and it is a heterodimer, composed of α1 and β1 subunits. The ferrous heme is ligated to the β1 subunit via H105 (1), and when NO is bound, the activity of the enzyme is 300-fold elevated over basal activity (2). sGC has evolved to selectively bind NO and not O2. It does not form a stable, isolable complex with O2, permitting NO to bind selectively to the Fe+2 heme in an aerobic environment. This selectivity is essential for sGC to trap nM concentrations of NO in the presence of a high competing concentration of O2.

sGC has been characterized in animals ranging from Drosophila to humans and, until recently, there had been no reports of any other NO sensors except for sGC. Notably, no heme-containing NO sensors had been found in prokaryotes, which could be exposed to both exogenous and endogenous NO (3). However, a PSI-BLAST search using β1 (1-194) as the query sequence led to multiple hits in prokaryotic genomes (4, 5). Two representative proteins were characterized—a 181 amino acid protein from V. cholerae (VCA0720) and the heme domain from the T. tengcongenesis Tar4 protein (TtTar4H) (6). VCA0720 is encoded in a histidine kinase containing-operon, while TtTar4H is fused to a methyl-accepting chemotaxis domain. These proteins share spectroscopic properties, sequence homology and key conserved residues with the sGC heme domain and, therefore, were placed in the same family. Surprisingly, however, these proteins exhibited very different ligand-binding properties. For example, our spectroscopic data indicated that the predicted heme domain from Vibrio cholerae had ligand binding characteristics essentially identical to sGC, while TtTar4H was able to form a stable ferrous-oxy complex similar to the O2-sensor AxPDEA1 (6). Our results suggested that these sGC-like heme domains have evolved specific ligand binding properties that allow them to function as sensors for NO or O2 and, therefore, we have named it the H-NOX (Heme-Nitric oxide/OXygen binding) domain.

Previously, we had localized the heme-binding region of sGC to residues 1-385 of the β-subunit (1, 7). β1(1-385) includes a predicted coil-coil region and is isolated as a homodimer although the associated spectral properties are essentially the same as those in the native enzyme. In an effort to determine the minimum sequence needed to retain the unique ligand binding properties of the heme in sGC, we truncated and characterized several new constructs. In this report we show that the N-terminal 194 residues of the β1 subunit retains the unique ligand binding properties of the full-length enzyme and appears to be the smallest functional β1 fragment. To further probe the selectivity of ligand binding in the sGC H-NOX domain, we have characterized this 194 amino acid β1 fragment representing the smallest sGC heme domain and the heme domain from the rat β2 subunit.

The β2 subunit is 43% identical to rat β1(1-194) (Figure 1) and was cloned from rat and kidney cDNA libraries (8-10). Its primary localization appears to be the kidney and liver (8). Unlike the β1 subunit, it contains an isoprenylation motif at its C-terminus which could lead to membrane localization (8). The functional relationship between the β1 and β2 subunits is not presently well characterized. Because of their sequence similarity, it has been hypothesized that both subunits function to sense NO, but this has not been definitively demonstrated. Two recent reports have described NO-stimulated β2 cyclase activity in over-expressed cells, although the stimulation was much weaker compared to α1/β1 heterodimeric sGC (10, 11). Thus, it appears that this subunit is a catalytically active NO-sensing homodimer, although no studies have been performed on purified protein. In this report we show that β2(1-217) is able to form a 5-coordinate NO complex and is unable to form a stable Fe+2−O2 complex as has been observed for native sGC and the β1 subunit.

Figure 1.

Alignment of rat β1(1-194) with rat β2(1-217) and the Thermoanaerobacter tengcogensis H-NOX domain. The alignment was generated using DNASTAR's Megalign program and the Clustal W algorithm. Conserved residues that are identical to the consensus sequence are shaded in black. Conserved residues discussed in the text are marked with an asterisk (His105, the heme ligand, and Tyr135, Ser137 and Arg139 using the rat β1 numbering).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of expression plasmids

PCR (PfuTurbo, Stratagene) was used to amplify β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) from β1(1-385) and the full-length rat β2 clone (containing the additional N-terminal 60 amino acids) (10), respectively. The upstream primers were 5'-ggaattccatatgtacggttttgtgaaccatgcc-3' and 5'-ggaattccatatgtatggattcatcaacacctgc-3' and the downstream primers were 5'- atagtttagcggccgctcaatcttcataaaaatcctcttcttttg-3' and 5'-atagtttagcggccgctcaaaggagtgttccctggagagcctc-3' for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively. Primers were obtained from Qiagen except for the upstream primer for β2(1-217), which was obtained from GibcoBRL. Amplified PCR products were cloned into pET-20b (Novagen) and sequenced (UC Berkeley sequencing core and Elim Biopharmaceuticals, Inc).

Protein expression

Expressions were performed as described previously (1) with the following modifications. Plasmids were transformed into Tuner DE3 plysS cells (Novagen). Cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.5-0.6 and cooled to 27 °C. IPTG (Promega) was added to 10 μM and aminolevulinic acid to 1 mM. Cultures were grown overnight for 14-18 h and then harvested.

Protein purification

β1(1-194) was purified in the following manner: Frozen cell pellets from 3 L of culture were thawed quickly at 37 °C and resuspended in 120 mL of Buffer A (50 mM DEA pH 8.5, 20 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM Pefabloc (Pentapharm) and 5% glycerol). Resuspended cells were lysed with sonication and, subsequently, with an Emulsiflex-C5 high pressure homogenizer at 20,000 psi (Avestin, Inc). Lysed cells were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 40 min. The supernatant was collected and reduced with ∼500-fold excess dithionite, which was based on a final yield of 20 mg of pure protein (dithionite was used throughout the prep to keep the protein reduced because it oxidized over several hours and sometimes aggregated when oxidized. To minimize unwanted side effects of dithionite in aerobic conditions, we purged all of the chromatography buffers with nitrogen gas before use). The supernatant was applied to a 50 mL (2.5 × 11 cm) Toyopearl SuperQ 650 M (Tosohaas) anion exchange column at 2.5 mL/min. The column was washed with 2 column volumes of Buffer A at 2.5 mL/min and eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl from 20 to 750 mM in a total volume of 340 mL at 3.5 mL/min. Fractions were selected on the basis of the intensity of the red/brown color. The eluate (50 mL) was concentrated to 4 mL using 15 mL 10K MWCO spin concentrators (Millipore) and reduced with ∼100-fold excess dithionite. The concentrated proteins were applied to a pre-packed Superdex S75 HiLoad 26/60 gel filtration column (Pharmacia) that had been equilibrated with TEA pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5mM DTT and 5% glycerol. The flow rate was 1.5 mL/min. Fractions containing β1(1-194) were pooled, reduced with ∼100-fold excess dithionite and applied to a POROS HQ 7.9 mL (1 × 10 cm, 10 μm) anion exchange column (Applied Biosystems) that had been equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM TEA pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT and 5% glycerol). The column was washed with 3 column volumes of buffer B at 10 mL/min and developed with a linear gradient of NaCl from 50 to 500 mM in a total volume of 140 mL at the same flow rate. β1(1-194) containing fractions were pooled and stored at −70 °C. β2(1-217) was purified as described above except for the following modifications: Dithionite was not added before each chromatographic step as it did not readily oxidize and aggregate. Buffer A contained 50 mM DEA pH 8.5 and 25 mM NaCl, and the flow rate for loading in the first anion exchange step was 1.5 mL/min.. The supernatant was applied to a 100 mL (2.5 × 21 cm) Toyopearl DEAE 650M anion exchange column (Tosohaas) and washed with 3 column volumes of Buffer A. The column was developed with a linear NaCl gradient from 20 to 500 mM (800 mL) and the flow rate for loading, washing, and eluting was 1.2 mL/min. The high-resolution, anion exchange step included 5 mM DTT.

UV/vis spectroscopy

All spectra were recorded in an anaerobic cuvette on a Cary 3E spectrophotometer equipped with a Neslab RTE-100 temperature controller set at 10 °C. Spectra were recorded from proteins in a solution of 50 mM TEA pH 7.5 and 50 mM NaCl (Buffer C). Heme concentration was ∼7 μM. Protein samples were placed into the anaerobic cuvette in an anaerobic glove bag (Coy). Fe+2-unligated protein samples were prepared in the following manner: Purified protein was made anaerobic in an O2-scavenged gas train with 10 cycles of alternate evacuation and purging with purified argon and brought into an anaerobic glove bag. Because β1(1-194) was susceptible to oxidation, it was first reduced anaerobically using dithionite (∼100 equivalents). The dithionite was then removed using a PD10 desalting column that had been equilibrated with Buffer C. For consistency, β2(1-217) was prepared in the same manner. The CO complexes were generated by adding Fe+2-unligated protein to a sealed Reacti-Vial (Pierce) that contained CO (Airgas). NO complexes were generated by preparing an anaerobic solution of Diethylamine NONOate (Caymen) in Buffer C (∼10 mM) in a sealed Reacti-Vial. The head-space (1 mL) was then removed using a gas-tight syringe and delivered to a Fe+2-unligated protein sample contained in a sealed Reacti-Vial.

Extinction coefficient determination

An anaerobic, Fe+2-unligated, UV/vis spectrum was recorded for each protein sample. These samples, along with the Mb standard, were prepared anaerobically as described above with the following modification: bound-O2 was removed by ferricyanide oxidation (∼100 equivalents). The ferricyanide was then removed using a PD10 desalting column that had been equilibrated with Buffer C and then the protein was reduced using dithionite (∼100 equivalents). The dithionite was then removed in the same manner. For consistency, β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) were prepared in the same way. The heme concentration was then determined for each sample by HPLC (12) and used to determine the Fe+2-unligated extinction coefficient. This extinction coefficient was then used to determine the heme concentration and extinction coefficients for the CO and NO complexes from previously recorded UV/vis spectra. HPLC was used to determine the heme concentration using a protein C4 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Vydac) and a Hewlett Packard Series II 1090 HPLC with a diode array detector. Each sample (25 μL) was applied to the C4 column that had been equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The column was developed with a linear gradient of 0-75% acetonitrile over 15 min followed by a linear gradient of 75-95% acetonitrile over 5 min. The flow rate was 1 mL/min.

Homology modeling

Homology models of β1(1-194) and β2 (1-217) were generated using MODELLER following the methods described in (13).

Resonance Raman spectroscopy

Spectra of all samples were collected using 413.1 nm laser excitation except for the NO complexes, which were excited at 406.7 nm. A microspinning sample cell was used to minimize photo-induced degradation. Raman scattering was detected with a cooled, back-illuminated CCD (LN/CCD-1100/PB, Roper Scientific) controlled by a ST-133 controller coupled to a subtractive dispersion, double spectrograph (14). Raman spectra were corrected for wavelength dependence of the spectrometer efficiency by using a white lamp and calibrated with cyclohexane. The reported frequencies are accurate to ± 2 cm−1 and the resolution of the spectra is 8 cm−1. All Raman spectra were obtained by subtracting the buffer background and baseline correction. The laser power at the sample was 3 mW, except for the CO complexes where a power of 0.2 mW was used to avoid photolysis. Typical data acquisition times were 30 min.

All protein samples were placed into the Raman cell in an anaerobic glove bag. The heme concentration was 14 and 19 μM for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively. Protein samples for Raman spectroscopy were prepared as described above for UV/vis spectroscopy with the following modifications: 13CO (99% containing ∼10% 18O2, Cambridge Isotopes) was prepared in a similar manner to the 12CO complexes. 15NO complexes were made in the following manner: A 1 mL solution of 0.5 M K15NO2 (Cambridge Isotopes) and a 1 mL solution of 1M KI/H2SO4 were made anaerobic on an O2-scavenged gas train and delivered into the anaerobic glove bag. The potassium nitrite solution (100 μL) was delivered to the KI solution using a gas-tight syringe. 15NO-containing head-space (∼1 mL) was then delivered to a protein sample contained in a sealed Reacti-Vial.

Oxidation rates

Rat β1(1-194) and rat β2(1-217) (550 and 220 μM, respectively) were brought into an anaerobic chamber (Coy) and reduced at room temperature with sodium dithionite (20 mM final). Both proteins were then desalted using a PD-10 column and eluted in 50 mM triethanolamine, 50 mM NaCl. Each protein was then added to an anaerobic cuvette and removed from the chamber. Prior to acquiring the first spectra, each sample was diluted 5-fold with 50 mM triethanolamine, 50 mM NaCl that had been fully equilibrated with room air and the cuvette was then left open to atmospheric oxygen. Immediately (<10 second dead time) after dilution with the aerobic buffer, spectra were acquired (β1: 1 scan/minute for 100 minutes, β2: 1 scan/min for 60 minutes, 1 scan/10 minutes for 17 hours) at 37 °C. Rate constants based on double difference plots (β1: Δ404 – Δ434; β2: Δ390 – Δ432) were then calculated and fit to single exponentials of the form f(x) = A*(1-e(−k*x)).

RESULTS

Cloning, expression and purification

N-terminal sGC β1 heme-binding region fragments were generated by sub-cloning specific constructs into the E. coli expression vector pET-20b. The shortest region that was sub-cloned, had heme-bound and expressed well was β1(1-194). For example, β1(1-189) was cloned, expressed and purified and relative to the longer constructs it was poorly expressed and unstable. Therefore β1(1-194) was the specific construct that was chosen for further study.

For the β2 H-NOX domain, we initially attempted the expression of the full-length β2-subunit (10) and it was cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET-20b. After expression and purification the results clearly showed that a soluble heme-bound protein was made but appeared to be truncated, as demonstrated by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Mass spectral analysis yielded a heme-bound, N-terminal, 217 amino acid fragment confirming that the protein was indeed truncated (data not shown). It appears that an endogenous E. coli protease cleaved this fragment from the full-length protein. The 5651 bp of the rat β2-subunit coding for residues 1-217 was then cloned into pET-20b and further characterized.

β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) were expressed in E. coli and purified as described in materials and methods. These proteins were estimated to be > 95% pure on the basis of Coomassie staining of samples resolved by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Yields were ∼5 and 13 mg/L of cell culture for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively. β2(1-217) was isolated in the Fe+2-unligated state (Soret maximum ∼ 431 nm). Dithionite was needed to keep β1(1-194) reduced throughout the purification, because it was found to oxidize readily (see Materials and Methods). UV/vis and resonance Raman spectroscopy were then used to characterize the heme environment and ligand binding characteristics of both proteins.

UV/vis absorption spectroscopy

UV/vis spectra are shown in Figure 2 and the data with extinction coefficients summarized in Table 1 and compared to sGC (2) and hemoglobin (15). Details of the individual complexes are discussed where relevant below.

Figure 2.

Electronic absorption spectra of β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) showing the Soret maximum and α/β region. Reduced, unligated (—); CO complex (- - -); and NO complex (………). Heme concentration was ∼7 μM.

Table 1.

| protein | Soret | β | α | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe2+unligated | ||||

| sGC | 431 (111) | 555 (14) | (2) | |

| β1(1-194) | 431 (166) | 558 (17.7) | * | |

| β2(1-217) | 433 (155) | 557 (17.1) | * | |

| Hb | 430 (133) | 555 (12.5) | (15) | |

| CO-bound | ||||

| sGC | 423 (145) | 541 (14) | 567 (14) | (2) |

| β1(1-194) | 423 (235) | 541 (18.7) | 571 (17.6) | * |

| β2(1-217) | 424 (248) | 541 (18.1) | 570 (17.2) | * |

| Hb | 419 (191) | 540 (13.4) | 569 (13.4) | (15) |

| NO-bound | ||||

| sGC | 398 (79) | 537 (12) | 572 (12) | (2) |

| β1(1-194) | 400 (108) | 537 (16.5) | 570 (16.7) | * |

| β2(1-217) | 399 (121) | 543 (16.8) | 574 (18.1) | * |

| Hb | 418 (130) | 545 (12.6) | 575 (13.0) | (15) |

nm

mM−1 cm−1

this work

also a shoulder at 400 nm

Fe+2-unligated and CO complexes

These two β-subunit constructs have spectra that are similar to one another and to full-length sGC. The spectra of theFe+2-unligated hemes in both β-subunit constructs exhibit Soret bands at ∼431 nm and a single broad α/β band at ∼560 nm. Addition of CO to the anaerobically-reduced proteins resulted in CO complexes with sharp Soret bands at ∼424 nm, increases in the extinction coefficient and observable α/β bands. The shape and absorption maxima of the Soret and α/β bands for both the Fe+2-unligated and CO complexes are very similar to full-length sGC (2), suggesting that the reduced proteins are 5-coordinate, high-spin and the CO complexes are 6-coordinate, low-spin.

NO complexes

The NO complexes of β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) are similar to those of full-length sGC, exhibiting broadened Soret bands at ∼399 nm, decreases in the extinction coefficient and observable α/β bands. These spectra are identical to previously characterized 5-coordinate, NO complexes (2).

Resonance Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra are shown in Figures 3 and 4 (β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively) and the data summarized in Tables 2, 3 and 4 (Fe+2-unligated, CO adducts and NO adducts, respectively) along with comparisons to sGC (16, 17), Mb (18-23), Acetobacter xylinum PDEA1H (the heme domain of AxPDEA1) (24), rat sGC β1(1-385) (25), FixLN (the heme domain of FixL) (26), Alcaligenes xylosoxidans cyt c' (27, 28), HemAT-Bs (29), and CooA (30). Specific complexes are described below.

Figure 3.

β1(1-194) resonance Raman spectra. Fe+2-unligated in the low (a) and high frequency region (h); 14NO and 15NO complexes and their difference spectra in the low (b, c and d) and high frequency regions (i, j and k), respectively; 12CO and 13CO complexes and their difference spectra in the low (e, f and g) and high frequency regions (l and m), respectively. Heme concentration was 14 μM. The Raman intensity was normalized to the ν4 mode. The asterisks indicate subtraction artifacts.

Figure 4.

β2(1-217) resonance Raman spectra. Fe+2-unligated in the low (a) and high frequency region (h); 14NO and 15NO complexes and their difference spectra in the low (b, c and d) and high frequency regions (i, j and k), respectively; 12CO and 13CO complexes and their difference spectra in the low (e, f and g) and high frequency regions (l and m), respectively. Heme concentration was 19 μM. The Raman intensity was normalized to the ν4 mode. The asterisks indicate subtraction artifacts.

Table 2.

Heme Skeletal Vibrations and Vibrational Modesa: Fe+2-unligated proteins

| protein | csb | ν10 | ν2 | ν3 | ν4 | Fe-His | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sGC | 5 | 1606 | 1562 | 1471 | 1358 | 204 | (16, 17) |

| β1(1-385) | 5 | 1607 | 1563 | 1474 | 1358 | 206 | (25) |

| β1(1-194) | 5 | 1608 | 1568 | 1476 | 1359 | 208 | * |

| β2(1-217) | 5 | 1609 | 1567 | 1477 | 1359 | 207 | * |

| TtTar4H | 5 | 1600 | 1575 | 1471 | 1354 | 218 | (6) |

| Mb | 5 | 1607 | 1563 | 1471 | 1357 | 220 | (18) |

| HemAT-Bs | 5 | nrc | 1558 | 1469 | 1352 | 225 | (29) |

| AxPDEA1H | 5 | 1607 | 1557 | 1469 | 1354 | 212 | (24) |

| Axcyt c' | 5 | 1603 | 1577 | 1469 | 1351 | 231 | (27) |

cm−1

coordination state

this work

not reported

Table 3.

Heme Skeletal Vibrations and Vibrational Modesa: CO complexes

| protein | csb | ν10 | ν2 | ν3 | ν4 | ν(Fe-CO) | ν(C-O) | δc | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sGC | 6 | 1629 | 1583 | 1500 | 1371 | 472¶/487 | 1987 | 562 | (16, 17) |

| β1(1-385) | 6 | ndd | 1582 | 1496 | 1373 | 478¶/494 | 1987 | 564 | (25) |

| β1(1-194) | 6 | 1631 | 1586 | 1502 | 1375 | 477/496 | 1968 | 574 | * |

| β2(1-217) | 6 | 1629 | 1586 | 1493 | 1372 | 476 | 1994 | 559 | * |

| TtTar4H | 6 | 1620 | 1580 | 1496 | 1369 | 490 | 1989 | 567 | (6) |

| Mb | 6 | 1637 | 1587 | 1498 | 1372 | 512 | 1944 | 577 | (21) |

| HemAT-Bs | 6 | nre | 1578 | 1495 | 1368 | 494 | 1964 | nr | (29) |

| AxPDEA1H | 6 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 493 | 1973 | 581 | (24) |

| Axcyt c' | 6 | nof | 1596 | nr | 1368 | 491 | 1966 | 572 | (27) |

cm−1

coordination state

Fe-C-O bending mode

represents the dominant frequency

not determined

this work

not reported

not observed

Table 4.

Heme Skeletal Vibrations and Vibrational Modesa: NO complexes

| protein | csb | ν10 | ν2 | ν3 | ν4 | ν(Fe-NO) | ν(N-O) | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sGC | 5 | 1646 | 1584 | 1509 | 1375 | 525 | 1677 | (16, 17) |

| β1(1-194) | 5 | 1647 | 1586 | 1510 | 1376 | 526 | 1677 | * |

| β1(1-385) | 5 | 1646 | 1585 | 1509 | 1376 | 526 | 1676 | (25) |

| β2(1-217) | 5 | 1646 | 1586 | 1510 | 1376 | 527 | 1676 | * |

| TtTar4H | 6 | 1625 | 1580 | 1496 | 1370 | 553 | 1655 | (6) |

| Mb | 6 | 1638 | 1584 | 1501 | 1375 | 554 | 1624 | (19, 20) |

| Axcyt c' | 5 | 1641 | 1592 | 1506 | 1373 | 526 | 1661 | (27) |

| Axcyt c' | 6 | 1638 | 1596 | 1504 | nrd | 579 | 1624 | (28) |

| FixLN (20 °C) | 6 | 1632 | nr | 1498 | nr | 558 | noe | (26) |

| FixLN (20 °C) | 5 | 1646 | nr | 1509 | nr | 525 | 1676 | (26) |

| AxPDEA1H | 6 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 560 | 1637 | (24) |

| Mb(H64V) | 6 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 557 | 1640 | (22) |

| Mb(H93G) | 5 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 535 | 1670 | (22) |

| Mb(H64V/H93G) | 5 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 534 | 1684 | (22) |

| CooA | 5 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 523 | 1672 | (30) |

| Mb H93Y | 5 | nr | nr | nr | nr | 524 | 1672 | (23) |

cm−1

coordination state

this work

not reported

not observed

Fe+2-unligated complexes

In the high frequency region the heme skeletal marker bands are observed. These include ν4, which is sensitive to the oxidation state of the heme, and ν3 and ν2, which are sensitive to the spin and coordination state of the heme iron (31). The heme-skeletal markers are similar to the corresponding bands in histidine-ligated, 5-coordinate, high-spin, Fe+2 heme proteins like sGC. In the low frequency spectrum, bands at 208 and 207 cm−1 are observed for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively. These bands are assigned to the ν(Fe-His) stretching mode, on the basis of previous observations that in most histidine-ligated, Fe+2-heme complexes, this stretching frequency is usually between 200 and 250 cm−1 (32), and that in the NO and CO adducts this band was absent. We conclude that, when reduced, these proteins contain a 5-coordinate, high-spin heme.

CO complexes

The heme skeletal markers in the high frequency region are similar to the corresponding bands from histidine-ligated, 6-coordinate, low-spin, Fe+2 heme proteins like sGC. In the low-frequency spectrum, isotope-sensitive bands are observed at 477 and 496 cm−1 for β1(1-194) and 476 cm−1 for β2(1-217). These bands are assigned to the ν(Fe-CO) stretching mode on the basis of their isotopic shift and their similarity to the ν(Fe-CO) frequency for full-length sGC (472/487 cm−1) and other 6-coordinate, low-spin heme proteins (Table 2). The two ν(Fe-CO) frequencies in full-length sGC are likely due to different Fe-CO conformations (25) and this may also account for the two ν(Fe-CO) frequencies in β1(1-194). In the high-frequency spectrum, isotope-sensitive bands are observed at 1968 and 1994 cm−1 for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively. These bands are assigned to the ν(CO) stretching mode on the basis of their isotopic shift and their similarity to the ν(CO) frequencies of sGC (1987 cm−1) and of HemAT-Bs (1964 cm−1) (Table 2). Like sGC, β2(1-217) has a high ν(CO) stretching frequency. Therefore, β2(1-217) forms a CO complex that is the most similar to sGC. These complexes are 6-coordinate, low-spin and are notable for their high ν(CO) stretching frequency. CO-β1(1-194) is also 6-coordinate, low-spin like sGC, but its ν(CO) frequency is closer to that of proteins with lower values, like HemAT-Bs (1964 cm−1).

NO complexes

For β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), the high frequency spectra exhibit heme-skeletal marker bands that are similar to the corresponding bands in 5-coordinate NO-sGC. In the low-frequency spectra, isotope-sensitive bands are observed at 526 and 527 cm−1 for β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), respectively. These bands are assigned to the ν(Fe-NO) stretching mode based on their isotopic shift and similarity to the ν(Fe-NO) frequency in sGC (525 cm−1). Isotope-sensitive bands are also observed in the high frequency spectra (1676 and 1677 cm−1 for β2(1-217) and β1(1-194), respectively). Based on their isotopic shift and similarity to the ν(NO) frequency in sGC (1677 cm−1), these bands are assigned to the ν(NO) stretching mode. These data indicate that the NO complexes of β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) are 5-coordinate and similar to sGC.

Oxidation rates

Rat β1(1-194) was found to oxidize very quickly compared to full-length sGC which is very stable to oxidation (Figure 5). When averaged over three experiments the autoxidation rate of β1(1-194) was 0.073 per minute. Rat β2(1-217) was substantially more stable in the ferrous form with an autoxidation rate of 0.003 per minute at 37 °C. It should be noted that while β1 appears to cleanly convert from a 5-coordinate, high-spin Fe(II) complex (Soret λmax at 431 nm) to a 5-coordinate, high-spin Fe(III) complex (Soret maximum at 390 nm), the β2 oxidation is more complex. The high-spin, ferrous unligated (Soret λmax at 432 nm) protein appears to oxidize to a mixture of high and low spin ferric complexes (Soret λmax at 393 and 415, respectively). To support this conclusion, after oxidation with potassium (Fe(CN)6)3− the protein first forms a high spin complex (Soret λmax at 393 nm) which then converts to a mixture of high and low spin complexes (broad Soret λmax at 415 nm) (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Autoxidation rates of β1(1-194) and β2(1-217). Shown in panel A are difference spectra associated with the autoxidation of β1(1-194) and panel B shows a plot of the Δ434 – Δ404 versus time and a fit (grey line) to the data from which a rate constant was derived. Panel C shows the difference spectra for the autoxidation of β2(1-217) and panel D shows a plot of Δ432 - Δ390 versus time and a fit to those data (grey line).

DISCUSSION

The essential feature of sGC is the use of a ferrous heme with histidyl ligation to trap low concentrations of NO in the presence of a much higher O2 concentration. The heme in sGC shows no measurable affinity for O2, hence there is no competition for NO against a severe concentration gradient. The molecular basis for this remarkable ligand discrimination against O2 has not been clear until recent findings that sGC-like heme domains are present in prokaryotes. Characterization of these proteins has provided a molecular basis for this ligand discrimination (5, 6, 33). Since some members of the family form a stable complex with O2, we have named the family H-NOX (Heme-Nitric oxide/Oxygen) to more fully describe the family in terms of its ligand binding properties.

Prior to the discovery of the H-NOX family the strategy to characterize the sGC heme was focused on truncations of the β1-subunit in an effort to identify a stable heme domain fragment. These studies had identified a 385 amino acid fragment of the β1 subunit that retained the unique ligand binding properties of native sGC (1, 7). However, all attempts to crystallize this fragment failed and we surmised that this failure was due to the tendency of this protein to form an unnatural homodimer. Based on this, constructs were designed to determine the minimum size of the β1 fragment that retained the native ligand binding properties. Several constructs were generated and characterized; the smallest a 194 amino acid fragment. Any construct smaller than this (1-189 for example) could not be isolated with a full equivalent of heme and gave low yields upon purification, suggesting that ∼190 amino acids is the minimum fragment for a stable heme domain.

β1(1-194) was examined further as reported here, but perhaps more importantly, this fragment served as a query sequence for genome searching that led us to the H-NOX family. In two recent papers we have described two of these H-NOXs. The first protein was a 181 amino acid protein from V. cholerae (VCA0720), and the other was a 188 amino acid heme domain fragment from the T. tengcongensis Tar4 protein (TtTar4H) (6). The heme domain from V. cholerae has ligand binding properties like that of sGC, namely the ferrous protein does not form an O2 complex but does form stable complexes with NO and CO. The T. tengcongensis heme domain on the other hand forms a very stable ferrous O2 complex and like the globins will also form a CO and a NO complex. We have also determined the crystal structure of the heme domain from T. tengcongensis which, as mentioned above, provided a molecular explanation for the discrimination against O2 in the sGC-like proteins (5, 33). In fact, based on the structure of the T. tengcongensis H-NOX, we have recently converted β1(1-385) into a protein that now forms a stable Fe(II)–O2 complex (33).

Although the β1(1-194) construct is the smallest fragment that was stable enough to characterize, it is clear that it is not as stable as sGC. The rate of oxidation to Fe(III) is very slow in sGC and as shown in Figure 5, occurs much more quickly in β1(1-194). The Fe(II) unliganded, Fe(II)–NO, and Fe(II)–CO complexes are all identical to sGC, however, once the Fe(II) unliganded complex is exposed to air, oxidation occurs. A Fe(II)–O2 complex is not observed during oxidation and the molecular steps involved in the oxidation are unknown. β2(1-217) on the other is much more stable (Figure 5) and more comparable to sGC and the previously characterized β1(1-385) in this respect. β2(1-217) is 43% identical to the β1 subunit and shares the key spectroscopic properties of sGC. Specifically, the Fe+2-unligated forms of these proteins are 5-coordinate, high-spin and the CO complexes are 6-coordinate, low-spin.

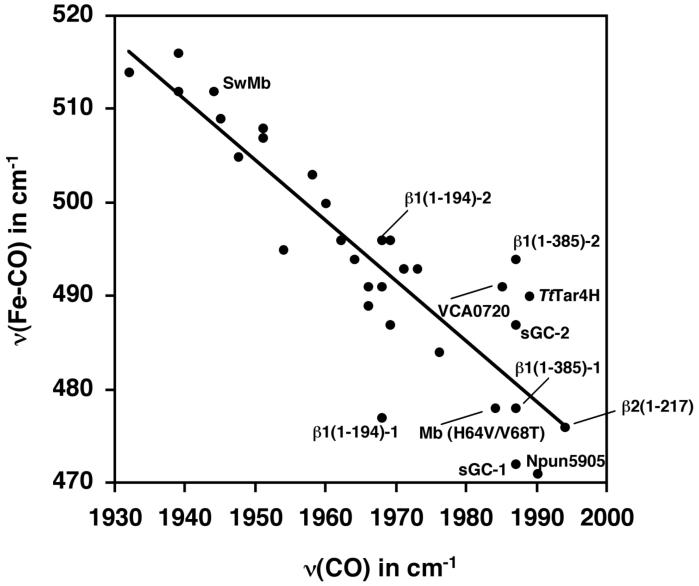

Moreover, like sGC, both β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) form a CO complex with unusually high ν(CO) and low ν(Fe-CO) stretching frequencies. sGC has one of the highest reported ν(CO) stretching frequencies, and, based on this observation, it was previously suggested that the distal pocket of sGC has significant negative polarity (34). This is based on the observation that the ν(CO) and ν(Fe-CO) frequencies are inversely correlated and are sensitive to distal pocket polarity (35, 36). Negative polarity in the distal pocket can inhibit Fe dπ→ CO π* back-bonding, weakening the Fe-CO bond order and strengthening the C-O bond order. However, a homology model of β1(1-194) and β2(1-217) based on the structure of the TtTar4H H-NOX shows no significant region of negative polarity that is close to the bound ligand. Figure 6 shows this model when viewed from below the heme and looking up into the distal pocket. Tyr140 is clearly visible in the T. tengcongensis H-NOX distal site but there is no H-bonding donor or residue that would provide negative polarity in either model of β1(1-194) or β2(1-217) suggesting that the negative polarity hypothesis may not be correct. A ν(Fe-CO)/ν(CO) correlation, which was generated from model porphyrin and hemoprotein frequencies, is shown in Figure 7. The closest ν(CO) and ν(Fe-CO) frequencies to sGC are from a Mb mutant (H64V/V68T) which increases negative polarity in the distal pocket (37). The high ν(C-O) and low ν(Fe-CO) stretching frequencies observed in β1(1-194) and β2(1-217), while consistent with distal pockets containing negative polarity, would seem to be dependent on other factors.

Figure 6.

Homology models of the distal pockets. Homology models of the β1 and β2 were generated using MODELLER following the methods described in (13). The view in the model is from below the heme and looking up into the distal pocket. H-bonding donors or residues that would provide negative polarity are shown in light grey. Tyr140 in the TtTar4H distal site is clearly visible, however, there is none visible in either model of β1(1-194) or β2(1-217).

Figure 7.

ν(Fe-CO)/ν(CO) correlation for 6-coordinate CO adducts of model porphyrins and hemoproteins. Values for the metalloporphyrins and hemoproteins were obtained from: Kerr et al., Table 2, complexes 1-15 (38); Table 3 in this work; CooA (39, 40); EcDosH (24); BjFixL (24); Heme oxygenase (41, 42); Sperm whale (Sw) Mb (21); Mb (H64V/V68T) (37). For sGC, β1(1-385) and β1(1-194), the numeric suffix refers to the CO conformation with the low and high ν(Fe-CO) frequency (1 and 2, respectively).

β1(1-194) has higher ν(Fe-CO) and lower ν(CO) frequencies compared to sGC. For example, the ν(CO) frequency is observed at 1968 cm−1 compared to 1987 cm−1 for sGC. Moreover, a broad band with two peaks of roughly equal intensity at 477 and 496 cm−1 were observed for the ν(Fe-CO) stretching frequencies. Two frequencies were also observed for sGC and for the previously characterized heme-binding region β1(1-385) (25): An intense band at 472 cm−1 and a very weak shoulder at 487 cm−1 for sGC and an intense band at 478 cm−1 and a weaker one at 494 cm−1 for β1(1-385). Although the two bands observed in sGC and β1(1-385) have been attributed to different CO conformations, no definitive results have emerged to support this hypothesis.

β2(1-217) is very similar to the heme domain of sGC in that it is unable to form a stable Fe+2-O2 complex but does form a 5-coordinate complex with NO. If we assume that the ligand binding characteristics of β2(1-217) is representative of the full-length subunit, an assumption that is consistent with reduced β1(1-194) being spectrally similar to full-length sGC, then it is likely that the β2-subunit also senses NO. These results are consistent with two reports that show NO-sensitive guanylate cyclase activity in β2-expressing cells. The first showed NO-stimulated activity in rat β2-expressing SF9 cell lysates (10) and the second in rat β2-expressing COS 7 cell lysates (11). Although the enzyme was not purified, the conclusion was that homodimeric β2 was the active protein. This would be the first example of a sGC that contained two heme cofactors per dimer and raises interesting questions regarding heme occupancy and regulation.

In summary, this report has identified and characterized the minimum functional ligand binding heme domain derived from sGC. This 194 amino acid N-terminal fragment was then used to identify prokaryotic homologs of predicted hemoprotein sensor domains that probably function as NO sensors in some organisms and O2 sensors in others. In addition, the ligand binding properties of a heme domain derived from the β2-subunit are reported. These results and others on this broadening family of proteins are providing key details towards a comprehensive characterization.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Chinmay Majmudar for help with the initial characterization of β1(1-194) and Dr. Elizabeth Boon for critical input.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by LDRD fund of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Abbreviations: CO, carbon monoxide; sGC, soluble guanylate cyclase; NO, nitric oxide; TtTar4H, N-terminal 188 amino acids of Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis Tar4 (heme domain); MCP, methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein; AxPDEA1H, Acetobacter xylinum phosphodiesterase A1 heme domain; Mb, myoglobin; H-NOX domain, Heme-Nitric oxide/OXygen binding domain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhao Y, Marletta MA. Localization of the heme binding region of soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15959–15964. doi: 10.1021/bi971825x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone JR, Marletta MA. Soluble Guanylate Cyclase from Bovine Lung: Activation with Nitric Oxide and Carbon Monoxide and Spectral Characterization of the Ferrous and Ferric States. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5636–5640. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watmough NJ, Butland G, Cheesman MR, Moir JW, Richardson DJ, Spiro S. Nitric oxide in bacteria: synthesis and consumption. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1411:456–474. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iyer LM, Anantharaman V, Aravind L. Ancient conserved domains shared by animal soluble guanylyl cyclases and bacterial signaling proteins. BMC Genomics. 2003;6:490–497. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pellicena P, Karow DS, Boon EM, Marletta MA, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of an oxygen binding H-NOX domain related to soluble guanylate cyclases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:12854–12859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405188101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karow DS, Pan D, Pellicena P, Presley A, Mathies RA, Marletta MA. Spectroscopic characterization of the sGC-like heme domains from Vibrio cholerae and Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10203–10211. doi: 10.1021/bi049374l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, Schelvis JP, Babcock GT, Marletta MA. Identification of histidine 105 in the beta1 subunit of soluble guanylate cyclase as the heme proximal ligand. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4502–4509. doi: 10.1021/bi972686m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuen PST, Potter LR, Garbers DL. A new form of guanylyl cyclase is preferentially expressed in rat kidney. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10872–10878. doi: 10.1021/bi00501a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrends S, Vehse K. The β2 subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase contains a human- specific frameshift and is expressed in gastric carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;271:64–69. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koglin M, Vehse K, Budaeus L, Scholz H, Behrends S. Nitric oxide activates the β2 subunit of soluble guanylyl cyclase in the absence of a second subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:30737–30743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibb BJ, Wykes V, Garthwaite J. Properties of NO-activated guanylyl cyclases expressed in cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;139:1032–1040. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brandish PE, Buechler W, Marletta MA. Regeneration of the ferrous heme of soluble guanylate cyclase from the nitric oxide complex: acceleration by thiols and oxyhemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16898–16907. doi: 10.1021/bi9814989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiser A, Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:461–91. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan D, Ganim JE, Kim JE, Verhoeven MA, Lugtenburg J, Mathies RA. Time-resolved resonance Raman analysis of chromophore structural changes in the formation and decay of rhodopsin's BSI intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4857–4864. doi: 10.1021/ja012666e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Iorio EE. Preparation of derivatives of ferrous and ferric hemoglobin. In: Antonini E, Rossi-Bernardi L, Chiancone E, editors. Hemoglobins. Academic Press; New York: 1981. pp. 57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deinum G, Stone JR, Babcock GT, Marletta MA. Binding of nitric oxide and carbon monoxide to soluble guanylate cyclase as observed with resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1540–1547. doi: 10.1021/bi952440m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomita T, Ogura T, Tsuyama S, Imai Y, Kitigawa T. Effects of GTP on bound nitric oxide of soluble guanylate cyclase probed by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10155–10160. doi: 10.1021/bi9710131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi S, Spiro TG, Langry KC, Smith KM, Budd DL, La Mar GN. Structural correlations and vinyl influences in resonance Raman spectra of protoheme comlexes and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4345–4351. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsubaki M, Yu NT. Resonance Raman investigation of nitric oxide bonding in nitrosylhemoglobin A and -myoglobin: detection of bound N-O stretching and Fe-NO stretching vibrations from the hexacoordinated NO-heme complex. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1140–1144. doi: 10.1021/bi00535a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu S, Kincaid JR. Resonance Raman spectra of the nitric oxide adducts of ferrous cytochrome P450cam in the presence of various substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9760–9766. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsubaki M, Srivastava RB, Yu NT. Resonance Raman investigation of carbon monoxide bonding in (carbon monoxy)hemoglobin and -myoglobin: detection of Fe-CO stretching and Fe-C-O bending vibrations and influence of the quaternary structure change. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1132–1140. doi: 10.1021/bi00535a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas MR, Brown D, Franzen S, Boxer SG. FTIR and resonance Raman studies of nitric oxide binding to H93G cavity mutants of myoglobin. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15047–15056. doi: 10.1021/bi011440l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogel KM, Hu S, Spiro TG, Dierks EA, Yu AE, Burstyn JN. Variable forms of soluble guanylyl cyclase: protein-ligand interactions and the issue of activation by carbon monoxide. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:804–813. doi: 10.1007/s007750050354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomita T, Gonzalez G, Chang AL, Ikeda-Saito M, Gilles-Gonzalez MA. A comparative resonance Raman analysis of heme-binding PAS domains: heme iron coordination structures of the BjFixL, AxPDEA1, EcDos, and MtDos proteins. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4819–4826. doi: 10.1021/bi0158831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schelvis JP, Zhao Y, Marletta MA, Babcock GT. Resonance raman characterization of the heme domain of soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16289–16297. doi: 10.1021/bi981547h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukat-Rodgers GS, Rodgers KR. Characterization of ferrous FixL-nitric oxide adducts by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4178–4187. doi: 10.1021/bi9628230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrew CR, Green EL, Lawson DM, Eady RR. Resonance Raman studies of cytochrome c' support the binding of NO and CO to opposite sides of the heme: implications for ligand discrimination in heme-based sensors. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4115–4122. doi: 10.1021/bi0023652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrew CR, George SJ, Lawson DM, Eady RR. Six- to five-coordinate heme-nitrosyl conversion in cytochrome c' and its relevance to guanylate cyclase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2353–2360. doi: 10.1021/bi011419k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aono S, Kato T, Matsuki M, Nakajima H, Ohta T, Uchida T, Kitagawa T. Resonance Raman and ligand binding studies of the oxygen-sensing signal transducer protein HemAT from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13528–13538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds MF, Parks RB, Burstyn JN, Shelver D, Thorsteinsson MV, Kerby RL, Roberts GP, Vogel KM, Spiro TG. Electronic absorption, EPR, and resonance Raman spectroscopy of CooA, a CO-sensing transcription activator from R. rubrum, reveals a five-coordinate NO-heme. Biochemistry. 2000;39:388–396. doi: 10.1021/bi991378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiro TG, Li X-Y. Resonance Raman spectroscopy of metalloporphyrins. In: Spiro TG, editor. Biological Applications of Raman Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1988. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitagawa T. Heme protein structure and the iron-histidine stretching mode. In: Spiro TG, editor. Biological Applications of Raman Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1988. pp. 97–131. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boon EM, Huang SH, Marletta MA. A molecular basis for NO selectivity in soluble guanylate cyclase. Nature Chemical Biology. 2005;1:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nchembio704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Deinum G, Gardner MT, Marletta MA, Babcock GT. Distal pocket polarity in the unusual ligand binding site of soluble guanylate cyclase: implications for control of ●NO binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8769–8770. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cameron AD, Smerdon SJ, Wilkinson AJ, Habash J, Helliwell JR, Li T, Olson JS. Distal pocket polarity in ligand binding to myoglobin: deoxy and carbonmonoxy forms of a threonine68(E11) mutant investigated by X-ray crystallography and infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13061–13070. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li T, Quillin ML, Phillips GN, Jr., Olson JS. Structural determinants of the stretching frequency of CO bound to myoglobin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1433–1446. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biram D, Garratt CJ, Hester RE. In: Spectroscopy of Biological Molecules. Hester RE, Girling RB, editors. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge, UK: 1991. pp. 433–434. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu N, Kerr EA. Vibrational Modes of Coordinated CO, CN−, O2, and NO. In: Spiro TG, editor. Biological Applications of Raman Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1988. pp. 39–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchida T, Ishikawa H, Takahashi S, Ishimori K, Morishima I, Ohkubo K, Nakajima H, Aono S. Heme environmental structure of CooA is modulated by the target DNA binding. Evidence from resonance Raman spectroscopy and CO rebinding kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19988–19992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.19988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uchida T, Ishikawa H, Ishimori K, Morishima I, Nakajima H, Aono S, Mizutani Y, Kitagawa T. Identification of histidine 77 as the axial heme ligand of carbonmonoxy CooA by picosecond time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12747–12752. doi: 10.1021/bi0011476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi S, Ishikawa K, Takeuchi N, Ikeda-Saito M, Yoshida T, Rousseau DL. Oxygen-bound heme-heme oxygenase complex: Evidence for a highly bent structure of the coordinated oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:6002–6006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi S, Wang J, Rousseau DL, Ishikawa K, Yoshida T, Takeuchi N, Ikeda-Saito M. Heme-heme oxygenase complex: structure and properties of the catalytic site from resonance Raman scattering. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5531–5538. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]