Abstract

On the first day of development a circadian clock becomes functional in the zebrafish embryo. How this oscillator is set in motion remains unclear. We demonstrate that zygotic period1 transcription begins independent of light exposure. Pooled embryos maintained in darkness and under constant temperature show elevated non-oscillating levels of period1 expression. Consequently, there is no maternal effect or developmental event that sets the phase of the circadian clock. Analysis of period1 transcription, at the cellular level in the absence of environmental stimuli, reveals oscillations in cells that are asynchronous within the embryo. Demonstrating an autonomous onset to rhythmic period1 expression. Transcription of clock1 and bmal1 is rhythmic in the adult, but constant during development in light-entrained embryos. Transient expression of dominant-negative ΔCLOCK blocks period1 transcription, thus showing that endogenous CLOCK is essential for the transcriptional regulation of period1 in the embryo. We demonstrate a default mechanism in the embryo that initiates the autonomous onset of the circadian clock. This embryonic clock is differentially regulated from that in the adult, the transition coinciding with the appearance of several clock output processes.

Keywords: bmal, circadian clock, clock, ontogeny, period

Introduction

Circadian clocks have been demonstrated to exist in a wide variety of species. A model has been established where a transcription–translation auto-regulatory feedback loop forms the core of the circadian clock mechanism. The heterodimer, composed of CLOCK (CLK) and brain muscle ARNT-like (BMAL), binds to enhancers upstream of the period (per) and cryptochrome (cry) genes to initiate their transcription. The repressors PER and CRY interact with the CLK:BMAL heterodimer and thereby downregulate their own expression (Wager-Smith and Kay, 2000; Reppert and Weaver, 2001). On account of the plasticity of the circadian clock and redundancy of its components, a mutation resulting in the deficiency of a single gene does not always have a severe impact on the circadian phenotype (DeBruyne et al, 2006). Several arrhythmic clock (clk) mutants have been shown to exhibit mutations that cause the protein to function in a dominant-negative manner. In a mouse and Drosophila clk mutant, a deletion is located within the conserved Q-rich transactivation domain required for transcriptional activity, while domains necessary for binding the per promoter (bHLH) and dimerisation (PAS) are functional (Antoch et al, 1997; King et al, 1997; Allada et al, 1998; Darlington et al, 1998; Gekakis et al, 1998). Although the core circadian clock mechanism is highly conserved, several variations are present among different species (Young and Kay, 2001). One example of this is the regulation of clk transcription, which has been shown to oscillate in Drosophila and zebrafish but not in mouse (Sun et al, 1997; Bae et al, 1998; Whitmore et al, 1998; Shearman et al, 1999). In mouse CLK and BMAL complex formation is followed by its phosphorylation, which is an important factor in regulating the transcriptional activity of the heterodimer (Kondratov et al, 2003). Post-transcriptional modifications of clock proteins also play a role in the generation of circadian rhythms in other species (Kloss et al, 1998; Liu et al, 2000; Price and Kalderon, 2002). Peripheral clocks in Drosophila and zebrafish are directly entrained by light, indicating a high degree of cell autonomy (Plautz et al, 1997; Whitmore et al, 2000). Cellular circadian oscillations have been shown in mouse, rat and fish cell lines, demonstrating that peripheral oscillators are self-sustained, as they do not require the existence of a central pacemaker (Nagoshi et al, 2004; Welsh et al, 2004; Carr and Whitmore, 2005).

Studies of circadian output have provided evidence for the existence of a functional circadian clock during the early stages of zebrafish development (Kazimi and Cahill, 1999; Ziv et al, 2005; Vuilleumier et al, 2006). To understand how circadian clock onset is established, we studied the regulation of core molecular clock components under various conditions. We observed a light-independent initiation of zygotic per1 transcription on the first day of development. We demonstrate that in the absence of environmental stimuli a rhythm of per1 transcription is present in each cell of the embryo and that these oscillations are asynchronous. Light or temperature exposure is required to synchronise these cellular clocks in the developing embryo. Importantly, we demonstrate that during the first 3 days of development, clk1 and bmal1 transcription is not rhythmic in contrast to later stages. However, direct manipulations show that CLK is already functional on the first day of development. Thus suggesting key regulation of the circadian clock at the post-transcriptional level during zebrafish development. The onset of rhythmic clk1 and per1 transcription coincides with the appearance of several circadian clock output processes, such as rhythmic locomotor activity (Hurd and Cahill, 2002), and the circadian timing of DNA replication (Dekens et al, 2003).

Results and discussion

A fixed process on the first day of development

Zebrafish breed at dawn, and consequently development initiates at light onset. The embryo develops rapidly when reared at 28°C, after 1 day an embryo has most anatomical structures and several days later it is fully developed into a free-swimming larva. We analysed the expression profile of per1 during the first days of development using an RNase protection assay to gain insight into circadian clock onset. Under constant temperature and an alternating 12-h light–dark (LD) cycle, we observed a rhythm of per1 transcription during development (Figure 1A). per1 expression peaks at ZT3 (zeitgeber time) and reaches its trough at ZT15, with a 10:1 ratio in the expression level during day 2 (Figure 1D). When embryos are maintained under constant temperature and darkness (DD), per1 transcription initiates at the end of day 1 but does not appear to be rhythmic over subsequent cycles (Figure 1B and D). In addition, per1 is expressed at an intermediate level when compared with embryos on an LD cycle. Previous studies have demonstrated that a clock-driven rhythm of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (aanat) transcription and melatonin release is not detected when embryos are reared in DD (Kazimi and Cahill, 1999; Ziv et al, 2005; Vuilleumier et al, 2006). These observations together indicate that there is no maternal effect or developmental event that sets or maintains clock phase.

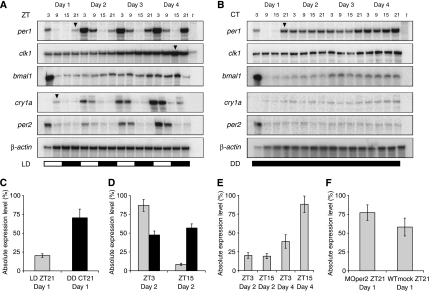

Figure 1.

Light is not required for the onset of zygotic per1 transcription. (A) RNase protection assay showing per1, clk1, bmal1, cry1a and per2 transcription pattern during the first days of development in pooled embryos raised under a 12:12 h LD cycle. The bar indicates light (white) and dark (black) intervals. tRNA serves as a negative control, and β-actin RNA detection as a loading control. Arrowheads indicate key changes in expression level. (B) RNase protection assay of pooled embryos raised in DD showing a constant level of per1, clk1, bmal1, cry1a and per2 transcription. (C) Comparison of per1 RNA levels at ZT21 on day 1 in embryos exposed to light for the first 12 h of development (LD), and those reared in constant darkness (DD) (P<0.0001, n=10). (D) per1 RNA levels at peak (ZT3) and trough (ZT15) time points on day2 in embryos exposed to an LD cycle (grey bars) (P<0.0001, n=10), and in DD (black bars) (P<0.05, n=10). (E) Comparison of clk1 RNA levels at ZT3 and ZT15 on days 2 and 4 in embryos exposed to an LD cycle (LD) (day 2: P>0.1, n=10 and day 4: P<0.0001, n=10). (F) Knockdown of part of the light input pathway. The effect of per2 morpholino on the level of per1 RNA at ZT21 on day 1 in embryos exposed to light for the first 12 h of development (P<0.005, n=10).

On the first day of development, the same fixed pattern of per1 transcription is observed in both embryos maintained under DD and those reared in an LD cycle (Figure 1A and B). Maternal per1 RNA degrades shortly after the mid-blastula transition when zygotic gene transcription starts, and is therefore present during the first 4 h post-fertilisation (h.p.f.). Zygotic per1 transcription reaches its maximum level at about 21 h.p.f. in DD, but the transcript can already be detected 6 h earlier at very low levels. The quantity of per1 RNA at 21 h.p.f. is four-fold higher in embryos maintained under DD compared with those reared in an LD cycle (P<0.0001; Figure 1C). Thus, the principal difference between the two conditions is the effect of light on the level of per1 expression at the end of the first day.

Previous studies have shown that zebrafish per1 is regulated through the binding of CLK and BMAL to E-box elements in the promoter region of this gene, a very similar mechanism to that reported for rhythmic period expression in mouse (Vallone et al, 2004). In addition, in zebrafish light inhibits CLK:BMAL function in part through the transcriptional activation of cry1a. The binding of the CRY1a protein to CLK and also BMAL prevents the formation of an active transcriptional complex, leading to the light-dependent repression of per1 (Figure 5B and C; Tamai et al, 2007). This process is thought to be one route by which the core clock mechanism is entrained to LD cycles in this system. We show here that cry1a transcription is increased on the first day of development as a result of light exposure, and has a more robust light-regulated rhythm throughout the subsequent days of development (Figure 1A). Therefore, we suggest that in the embryo, as in zebrafish cell lines, early light induction of cry1a leads to the repression of per1, and has a function in the entrainment of the embryonic clock. In addition, short light pulses applied on the first day of development acutely increase the level of per2 transcription (Tamai et al, 2004). In Figure 1, we show that per2 is rhythmic in embryos raised on an LD cycle when compared with minimal expression levels detected in DD. per2 transient knockdown on the first day of development has been demonstrated to affect the circadian clock-dependent process of aanat transcription (Ziv and Gothilf, 2006). Using the same morpholino-modified anti-sense oligonucleotide per2 ‘knockdown' protocol, in embryos exposed until 12 h.p.f. to light, we observe an increase in the per1 RNA level at 21 h.p.f. (P<0.005; Figure 1F). We demonstrate that the ‘knockdown' of per2 in light-treated embryos can partially block the light-induced suppression of per1, confirming that the light input pathway is functional within the first 12 h of development. However, the level of per1 RNA in these ‘knockdown' embryos does not reach the same level seen in DD. This observation most likely reflects the existence of multiple light input pathways to the core clock. Nevertheless, the key molecular difference between embryos raised in the dark and those on an LD cycle is the strong light induction of both cry1a and per2, two proteins that have been implicated in zebrafish clock entrainment.

Light-independent entrainment of per1 transcription

To determine whether the observed embryonic per1 transcriptional rhythm represents true circadian clock entrainment and not a light-driven response, embryos were subjected to light during the first 12 h of development followed by DD over the consecutive days. A rhythm of per1 RNA expression is observed on the days following this light exposure. Such light-dependent synchronisation could only occur if an oscillator is present, and thus reflects the presence of a functional circadian clock within the first 12 h of development (Figure 2A and B).

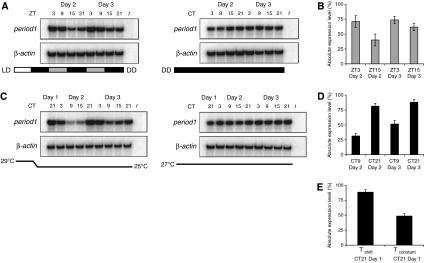

Figure 2.

Light-independent entrainment of the circadian clock on the first day of development. (A) per1 RNA levels on days 2 and 3 in pooled embryos after exposure to light until 12 h.p.f. followed by DD, and the corresponding DD control. Grey partitions of the bar indicate the timing of the subjective light period. (B) Comparison of per1 RNA levels at peak (ZT3) and trough (ZT15) time points on days 2 and 3 in embryos exposed to light for the first 12 h of development only (P<0.0005 on day 2, n=10). (C) per1 RNA levels on days 2 and 3 in pooled embryos after exposure to a temperature shift on day 1 (first 12 h.p.f. at 29°C) followed by constant temperature (25°C), and the corresponding constant temperature control (27°C, DD). (D) Comparison of per1 RNA levels at peak (CT21) and trough (CT9) time points on days 2 and 3 in pooled embryos after exposure to a temperature shift on day 1 followed by constant temperature (P<0.0001 on day 2, n=10) demonstrates that light is not required for inducing or synchronising oscillations in the embryo. (E) Comparison of per1 RNA level at ZT21 on day 1 in embryos exposed to a temperature shift and those maintained at constant temperature (P<0.0001, n=10).

The circadian clock can be entrained by several environmental stimuli including temperature (Lahiri et al, 2005). To determine whether light is specifically required for circadian clock function on the first day of development, we reared embryos in DD while exposing them to a change in temperature. Embryos were submerged in a 29°C water bath for the first 12 h of development and subsequently cooled to 25°C, whereas control embryos were exposed to a constant temperature of 27°C. Embryos exposed to a temperature shift show a significant increase in per1 expression at 21 h.p.f. when compared with those maintained at constant temperature; thus, a shift in temperature does influence the expression level of a core circadian clock gene as early as the first day of development (P<0.0001; Figure 2E). We then exposed embryos for the first 12 h to 29°C followed by a constant temperature of 25°C for several days to determine whether per1 RNA oscillations occur after the first day. Rhythmic expression of per1 RNA persists over days 2 and 3 following the temperature shift, demonstrating that exposure to light is not a prerequisite for early circadian clock function (P<0.0001; Figure 2C and D). Temperature cycles establish a different phase relationship with the timing of per1 expression in zebrafish when compared with light entrainment (Lahiri et al, 2005), and consequently we observed the trough and peak of expression at CT9 and CT21, respectively. The rhythm during the 2 days following the temperature shift dampened less than that induced by a single 12-h light treatment (Figure 2A and C), demonstrating that temperature can function as a strong zeitgeber at this early stage of development.

Asynchronous cellular oscillators in constant darkness

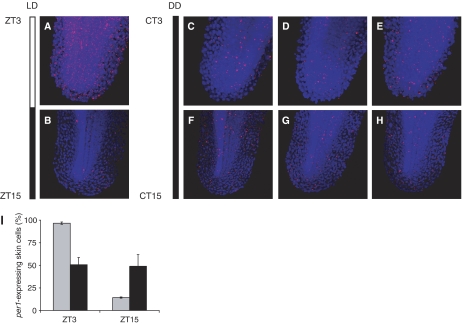

Pooled embryos not exposed to environmental stimuli show a constant level of per1 transcription. This phenomenon could be explained either by arrhythmic (non-synchronised) oscillations at the cellular level or constitutive per1 transcription, reflecting a non-functional clock. An indication that suggests the existence of ‘out-of-phase' oscillators is the intermediate level of per1 RNA present in embryos raised in DD. We performed a non-invasive experiment with cellular resolution to obtain insight into the default setting of the clock mechanism in embryos. We compared per1 transcription at peak (ZT3) and trough (ZT15) levels on the second day of development in embryos exposed to either an LD cycle or DD using whole mount fluorescent in situ hybridisation. By assessing the presence or absence of per1 RNA in single cells, one can draw a reliable conclusion, as to the state of the circadian clock within the organism. When analysing embryos exposed to an LD cycle, we observe per1 RNA expression in every cell at ZT3, this is in contrast to embryos at ZT15 where per1 expression is scarce throughout the embryo (Figure 3A and B, respectively). When embryos are raised in DD, an intermediate number of cells express per1 RNA at both time points (CT3 and CT15; Figure 3C–E and F–H). Individual siblings fixed at the same time point express a variable number and randomly distributed per1 transcript clusters (Figure 3I). This result supports the existence of asynchronous oscillations in DD, as in the case of constitutive per1 expression one would expect all cells to express intermediate levels of per1 RNA. Locomotor activity in zebrafish larvae is also arrhythmic in constant darkness, which could be explained by non-synchronous cellular oscillators (Hurd and Cahill, 2002). These data led us to propose that asynchronous oscillations are the default state in the absence of environmental stimuli. As the embryo already produces out-of-phase oscillations between individual cells in the dark, a light or temperature cue functions only as a signal to reset these clocks, causing overall synchronised oscillations within the embryo.

Figure 3.

The embryo generates asynchronous per1 RNA oscillations when raised in DD. (A) per1 transcript clusters (red) present in single cells (nuclei in blue), visualised by fluorescent in situ hybridisation, showing abundant per1 expression at ZT3 on day 2, and (B) sparse per1 expression at ZT15 on day 2 in an embryo exposed to an LD cycle. (C–E) per1 transcript clusters at CT3 on day 2 in tail tips of three sibling embryos reared in DD. (F–H) per1 transcript clusters in tail tips of three sibling embryos at CT15 on day 2 raised in DD. Both CT time points show a variable number and random distribution of high-level per1 RNA-expressing cells, demonstrating an autonomous and asynchronous onset of circadian oscillations in the cells of the zebrafish embryo. (I) Percentage of per1-transcribing skin cells at peak and trough time points under DD and LD conditions.

Differential regulation of clk1 and bmal1 between the embryo and adult

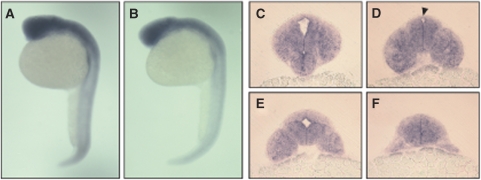

The transcription factor CLK has been demonstrated to have a pivotal function in the regulation of per in several species. In the adult zebrafish, clk1 transcription oscillates in all organs and cells studied to date (Whitmore et al, 1998). In contrast to per1, rhythmic transcription of clk1 starts several days after fertilisation in embryos exposed to an LD cycle (Figure 1A and E). clk1 RNA is constitutively expressed during the first days of development, with no significant difference being observed in expression level during day 2 in embryos on an LD cycle (Figure 1A and E). In addition, no oscillation in transcript levels was detected until day 4 under LD conditions of the partner of clk1, bmal1 (Figure 1A). Yet in cells and tissues, bmal1 transcription shows robust oscillations (Cermakian et al, 2000). Taken together, the clk1 and bmal1 expression patterns strongly suggest differential regulation of the core circadian clock mechanism during zebrafish development. Although the negative regulatory elements of the clock mechanism (per and cry genes) are already oscillating on the first day of development, oscillations in the positive acting transcriptional regulators (clk and bmal) take another 3 days to become established. Both per1 and clk1 transcripts are present and ubiquitously expressed during early stages of zebrafish development as demonstrated by in situ hybridisation (Figure 4A–F). A gradient is observed for both transcripts, with high levels of expression at the anterior, and low levels at the posterior region of the embryo.

Figure 4.

per1 and clk1 are expressed ubiquitously in the zebrafish embryo. (A) Whole mount in situ of per1, and (B) clk1 transcripts in embryos reared in an LD cycle and fixed at ZT3 on day 2 display a gradient of ubiquitous transcription with the highest level of expression at the anterior. Sections through the head (C–F) show no discrete region of the brain or retina at this stage, which due to a distinctive expression of per1 could be identified as the location of a centralised pacemaker (arrowhead indicates location of pineal gland).

Endogenous CLK autonomously initiates per1 transcription

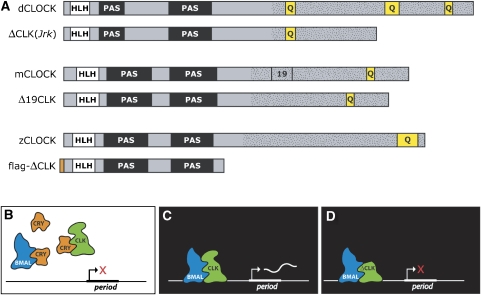

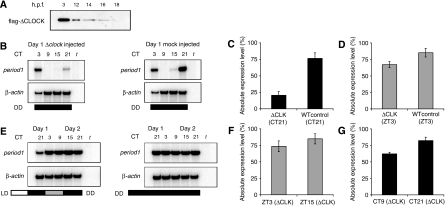

The fluorescent in situ result shows the presence of self-sustained circadian clocks in each cell of the embryo. Furthermore, transcriptional initiation of per1 at 15 h.p.f. also occurs independent of light exposure. Thus, a positive transcriptional activator, which can exert an effect on the per1 promoter during this time, must be present. We demonstrated that clk1 and bmal1 do not oscillate in an LD cycle throughout the first 3 days of development in contrast to later stages. This raises the major issue of whether the CLK:BMAL heterodimer is functional in the embryo. To determine whether endogenous CLK is required for the initiation and subsequent oscillations of per1 transcription, we established a transient ‘knockdown' approach. To overcome gene redundancy, we constructed a dominant-negative clk (Δclk) encoding a truncated protein consisting of the first 396 amino acids (Figure 5A and D). This design was based on mutations in previously isolated dominant-negative mutants where large deletions in the Q-rich transactivation domain have been reported to impair the circadian clock (King et al, 1997; Allada et al 1998, Gekakis et al 1998, Hayasaka et al 2002). A flag-tag sequence was introduced into the construct to confirm the expression of the protein. We microinjected Δclk RNA into zygotes and analysed samples taken during the first day on a western blot (Figure 6A). The earliest sample taken at 3 h.p.f. and a later sample at 12 h.p.f. show the presence of a large quantity of ΔCLK protein, by 18 h.p.f. ΔCLK has decreased to an undetectable level. We microinjected zygotes with Δclk RNA and transferred them immediately to DD to compare the level of per1 RNA at 21 h.p.f. with non-injected embryos. We did not observe a difference between mock-injected and non-injected embryos, thus mock injections were subsequently omitted. The level of per1 RNA at the end of the first day is high in embryos maintained under DD; however, when ΔCLK is expressed we observe a four-fold reduction of per1 RNA at 21 h.p.f. (P<0.0001; Figure 6B and C). This may be the maximum possible decrease in per1 RNA as the level is similar to that observed at 21 h.p.f. in embryos exposed to an LD cycle (Figure 1C). A minimal effect on per1 can still be observed at 27 h.p.f. (Figure 6D), this is several hours after detectable levels of ΔCLK are present on a western blot. The amount of ΔCLK expressed in the embryo is in vast excess of the endogenous CLK protein. Thus, the prolonged effect can be explained by the capacity of ΔCLK to efficiently block per1 transcription at much lower levels. The manipulation demonstrates that endogenous CLK protein is required for the transcriptional initiation of per1 on the first day of development.

Figure 5.

Design of a zebrafish dominant-negative CLK (ΔCLK). (A) Diagram of the Drosophila and mouse wild-type CLK proteins with corresponding dominant-negative mutations (white: helix-loop-helix domain; black: Per-Arnt-Sim domain; yellow: poly-Q box; dotted: Q-rich domain; orange: flag tag). A stop codon was introduced into the zebrafish clk1 cDNA to generate a truncated 396 amino-acid protein, containing the bHLH and PAS domains but lacking the glutamine-rich transactivation domain. This design is based on known dominant-negative CLK mutations in mouse and Drosophila, where a part of the glutamine-rich area is absent. The PAS and bHLH domains present allow binding of CLK to its partner BMAL, and of this heterodimer to the period promoter. The absence of part of the glutamine-rich area and/or glutamine box at the carboxyl-terminus abolishes the capacity of CLK to transactivate the period gene. (B) Wild-type condition. In the light (day) CRY1a is expressed, which binds to CLK and BMAL, thereby blocking period transcription. (C) In darkness (night), CLK and BMAL form a heterodimer, which binds to E-boxes in the promoter of the period gene, thereby activating its transcription. (D) The mutant dominant-negative CLK can form a heterodimer and dock onto E-boxes in the period promoter, thereby competing with wild-type CLK and blocking transcription.

Figure 6.

CLK is required for zygotic per1 transcription during development. (A) Western blot showing flag-ΔCLK expression on the first day of development in embryos microinjected with Δclk RNA (three times more protein was loaded for 14–18 h.p.f.). (B) Knockdown of the positive feedback loop. RNase protection assay showing per1 transcription levels during day 1 in pooled embryos microinjected with Δclk RNA and transferred directly to DD compared with mock-injected DD control embryos. (C) Comparison of per1 RNA level at CT21 on day 1 in embryos expressing ΔCLK and non-injected control embryos both maintained in DD (P<0.0001, n=10). This demonstrates the presence of functional CLK protein during the early stages of development. (D) Comparison of per1 RNA levels at ZT3 on day 2 in embryos expressing ΔCLK and non-injected control embryos both reared in an LD cycle (P<0.0001, n=10), demonstrating the reduced effect of ΔCLK protein at this stage. (E) RNase protection showing per1 transcription levels at the end of day 1 and during day 2 in embryos microinjected with Δclk RNA, exposed to light for the first 12 h only, and the corresponding control embryos maintained in DD. (F) Comparison of per1 RNA levels at ZT3 and ZT15 on day 2 in embryos transiently expressing ΔCLK on day 1 and exposed to light for the first 12 h only (P>0.05, n=10). (G) Comparison of per1 RNA levels at CT9 and CT21 on day 2 in embryos subjected on day 1 to a temperature shift while transiently expressing ΔCLK (P<0.0001, n=10). These data demonstrate that CLK, a core component of the positive feedback loop, is already functional on the first day of development, although rhythmic transcription starts several days later.

We have shown that exposure to light or a temperature shift on the first day of development alone results in per1 RNA oscillations on subsequent days. Thus, we examined whether the transient expression of ΔCLK in early embryos could abolish this effect. When zygotes are microinjected with Δclk RNA and exposed to light on the first day of development, a rhythm cannot be detected during the following day in DD (P>0.05; Figure 6E and F, compare with Figure 2B). Furthermore, expression of ΔCLK strongly dampened the per1 RNA rhythm observed on the day following a temperature shift (Figure 6G, compare with Figure 2D). Therefore, both light and temperature entraining signals exert an effect on the CLK transcription factor to synchronise the oscillator. Our results demonstrate that the CLK protein is essential for the onset of rhythmic per1 transcription, although oscillations in clk and bmal transcripts are not critical during the first days of development. Consequently, regulation of the CLK and BMAL proteins required for generating the per1 rhythm is most likely to occur at the post-transcriptional level, either through changes in protein degradation, phosphorylation or subcellular localisation. A precedent for this form of protein regulation has been reported for the mouse circadian system, where post-translational events are key to the generation of circadian rhythms (Kim et al, 2002; Kondratov et al, 2003). However, oscillations of CLK and BMAL are not always an absolute requirement for the generation of period rhythms (Zheng and Sehgal, 2008).

Ontogeny of a biological clock

The circadian clock starts autonomously within the first 12 h.p.f. The transcripts for numerous clock genes are maternally deposited in the embryo, including clk1, bmal1, per1, per2, but not cry1a. The levels of RNA decline rapidly between 3 and 9 h.p.f. for all of these genes, except for clk and bmal. Clearly, differential regulation of maternal RNAs is taking place in the context of clock molecules. Transcript levels for clk and bmal are elevated and constant until the fourth day of development in embryos subjected to LD cycles. We propose that these transcripts become active in the early night when cry is not expressed, leading to the increase in per1 RNA level at the end of the first day of development. This marks the autonomous onset of the first true embryonic clock cycle. However, when embryos do not experience an environmental entraining signal these oscillating clocks remain out of phase. The key difference between embryos raised on an LD cycle versus constant darkness is the light-dependent increase in cry1a and per2 levels, which act to synchronise these early embryonic clocks.

As the pineal becomes functional at 20–24 h.p.f., and the retina at the end of the third day of development (Wilson and Easter, 1991; Easter and Nicola, 1996; Gothilf et al, 1999), a functional circadian clock is present in the embryo far before differentiation of specialised light-receptive structures is completed. As the peripheral clock is established first, peripheral circadian clock oscillations must be ‘passed on' during differentiation to any developing central pacemaker cells. Rhythmic clk1 and bmal1 transcription first occurs on the fourth day of development. This transition may coincide with the development of the entire circadian system, and the phase during which the retina becomes functional (Easter and Nicola, 1996) followed by the retinal innervation of the putative zebrafish equivalent of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Burrill and Easter, 1994). This timing also corresponds to the gradual increase in the capacity of light to entrain circadian clock-regulated rhythmic locomotor activity (Hurd and Cahill, 2002). Furthermore, at this stage clock-gated rhythms in DNA replication are first established (Dekens et al, 2003). We demonstrated that clk1 transcription is not rhythmic until the fourth day of development, whereas endogenous CLK is crucial for circadian clock function at an early stage. Thus, the regulation of the zebrafish embryonic circadian clock is different from that in the adult. It is an interesting possibility that clock-dependent output processes might not be strongly regulated until the clk and bmal genes establish a high amplitude level of transcriptional oscillation. The study of the molecular regulation of core clock components during development gives important insight into the ontogeny of circadian rhythms, and how output processes as divergent as behaviour and cell division are coupled during development to the circadian clock.

Materials and methods

Animal maintenance

Zebrafish were raised following standard protocols (Mullins et al, 1994). Embryos were transferred to tissue culture flasks and submerged in thermostatically controlled water baths to maintain a constant temperature of 28°C. Embryos were illuminated with an Osram white fluorescent light source (180 μW/cm2).

RNase protection assay

RNA was extracted from embryos according to the manufacturer's protocol using TRIzol Reagent (Gibco BRL). The RNase protection assay was based on standard protocols (Gilman, 1993). For each sample, 8 μg total RNA was hybridised overnight at 55°C with [α-32P]UTP-labelled (Amersham) probe. For β-actin protections, 3 μg total RNA was hybridised and the quantity of label and probe were adjusted. Absolute expression levels were quantified by exposing radiographs to a phosphor screen (Bio-Rad) and scanned with the Pharos FX phosphor scanner. The density of the bands was determined using Quantity One software. The density measured in counts was normalised by setting the highest expression level to 100%. All data displayed in charts were calculated using a sample size of 10. The standard error of mean was used to indicate the confidence interval (95%, α=0.05). The significance of the difference observed between two treatments within one experiment was determined with the Student's t-test.

Transient ‘knockdown' protocols

The zebrafish CLK1 was truncated, thereby removing the carboxyl-terminal part containing the glutamine-rich area and poly-glutamine box (Figure 5A). The 1.2-kb clk1 fragment (HindIII/XhoI) and a flag sequence were cloned into the pCLNCX vector (Retromax) resulting in a frame shift, thereby introducing a stop codon. This truncated flag-Δclk1 sequence with stop codon was subcloned into pCS2+. Synthesis of capped mRNA was performed with the SP6 mMessage mMachine components from Ambion using linearised plasmid. The transcript was purified and 500 pg Δclk mRNA was microinjected into each zygote. This dose did not result in abnormal morphology or a decrease in survival rate. Transient knockdown of per2 was accomplished by microinjecting zygotes with a morpholino-modified anti-sense oligonucleotide (Gene Tools) (Nasevicius and Ekker, 2000) designed to match the per2 initiation of translation region (per2(AUG)MO: 5′-GGTCTTCAGACATCGGACTTGGGTT-3′) as previously described (Ziv and Gothilf, 2006).

Immunochemistry

Protein was extracted from embryos by shearing and low-speed centrifugation steps in 0.3 mM phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride (PMSF in Ringers; Roche), the supernatant was removed after each step, and the pellet was dissolved in cracking buffer with 1% β-mercaptoethanol and heated for 5 min at 95°C. Expression of ΔCLK protein was determined by western blot analysis and performed according to the manufacturer's manual (Bio-Rad). The flag-tagged ΔCLK was labelled with the primary rabbit α-flag (Sigma; F7425) and secondary goat α-rabbit peroxidase-coupled antibody (Cell Signaling Technology; 7074). Detection was performed using ECL (Amersham) and the blot was exposed to Kodak X-ray film for several hours.

In situ hybridisation

In situ hybridisation was performed with a 1.7-kb anti-sense per1 RNA fragment (SpeI/SphI) according to standard protocols (Schulte-Merker et al, 1992). Transcription and labelling for probe synthesis was executed using the Riboprobe Combination System from Promega, and digoxigenin-11-UTP (DIG) from Roche. After proteinase K treatment, the embryos were bleached with 5% peroxide (Sigma) in PBS-Tween under a bright light source. Embryos were hybridised at 63°C and thereafter labelled with sheep α-DIG alkaline phosphatase-coupled antibody (Roche) in 2% blocking reagent (Roche) and 10% goat serum (Sigma). Sections were cut after embedding stained embryos in Technovit 3040 (Heraeus Kulzer). Fluorescent in situ hybridisation was based on the standard in situ protocol with the following modifications: embryos were labelled with mouse IgG α-DIG peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Jackson Laboratories) in 25% lamb serum and PBST. For detection, the tyramide substrate (Cy3) was used from Perkin Elmer (NEL741) and nuclei were visualised with DAPI (Sigma).

Acknowledgments

We thank Amanda Carr and Daria Gavriouchkina for helpful discussions and critical reading of this paper. We are grateful to Mary Rahman, Linda Ariza-McNaughton and Chris Thrasivoulou for expert technical help. We thank Kathy Tamai, Silvia Castro, Gaia Gestri and Masatake Kai for technical advice. We thank Nicholas Foulkes for generously providing the β-actin protection and period1 in situ probes. This project was supported with funding from the Wellcome Trust.

References

- Allada R, White NE, So WV, Hall JC, Rosbash M (1998) A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian clock disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless. Cell 93: 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoch MP, Song E-J, Chang A-M, Vitatema MH, Zhao Y, Wilsbacher LD, Sangoram AM, King DP, Pinto LH, Takahashi JS (1997) Functional identification of the mouse circadian clock gene by transgenic BAC rescue. Cell 89: 655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae K, Lee C, Sidote D, Chuang KY, Edery I (1998) Circadian regulation of a Drosophila homolog of the mammalian Clock gene: PER and TIM function as positive regulators. Mol Cell Biol 18: 6142–6151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrill JD, Easter SS (1994) Development of the retinofugal projections in the embryonic and larval zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio). J Comp Neurol 346: 583–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A-J, Whitmore D (2005) Imaging of single light-responsive clock cells reveals fluctuating free-running periods. Nat Cell Biol 7: 319–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermakian N, Whitmore D, Foulkes NS, Sassone-Corsi P (2000) Asynchronous oscillations of two zebrafish CLOCK partners reveal differential clock control and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 4339–4344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington TK, Wager-Smith K, Ceriani MF, Staknis D, Gekakis N, Steeves TDL, Weitz CJ, Takahashi JS, Kay SA (1998) Closing the circadian loop: CLOCK-induced transcription of its own inhibitors per and tim. Science 280: 1599–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruyne JP, Noton E, Lambert CM, Maywood ES, Weaver DR, Reppert SM (2006) A clock shock: mouse CLOCK is not required for circadian oscillator function. Neuron 50: 465–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekens MPS, Santoriello C, Vallone D, Grassi G, Whitmore D, Foulkes NS (2003) Light regulates the cell cycle in zebrafish. Curr Biol 13: 2051–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easter SS, Nicola GN (1996) The development of vision in the zebrafish (Danio rerio). Dev Biol 180: 646–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gekakis N, Staknis D, Nguyen HB, Davis FC, Wilsbacher LD, King DP, Takahashi JS, Weitz CJ (1998) Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science 280: 1564–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman M (1993) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, pp 4.7.1–4.7.8. New York: John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- Gothilf Y, Coon SL, Toyama R, Namboodiri MA, Klein DC (1999) Zebrafish serotonin N-acetyltransferase: marker for pineal photoreceptor development and circadian-clock function. Endocrinology 140: 4895–4903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayasaka N, LaRue SI, Green CB (2002) In vivo disruption of Xenopus CLOCK in the retinal photoreceptor cells abolishes circadian melatonin rhythmicity without affecting its production levels. J Neurosci 22: 1600–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd MW, Cahill GM (2002) Entraining signals initiate behavioral circadian rhythmicity in larval zebrafish. J Biol Rhythms 17: 307–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazimi N, Cahill GM (1999) Development of a circadian melatonin rhythm in embryonic zebrafish. Dev Brain Res 117: 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Bae K, Ng FS, Glossop NRJ, Hardin PE, Edery I (2002) Drosophila CLOCK protein is under posttranscriptional control and influences light-induced activity. Neuron 34: 69–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DP, Zhao Y, Sangoram AM, Wilsbacher LD, Tanaka M, Antoch MP, Steeves TDL, Vitaterna MH, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, Turek FW, Takahashi JS (1997) Positional cloning of the mouse circadian Clock gene. Cell 89: 641–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloss B, Price JL, Saez L, Blau J, Rothenfluh A, Wesley CS, Young MW (1998) The Drosophila clock gene double-time encodes a protein closely related to human casein kinase I ɛ. Cell 94: 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondratov RV, Chernov MV, Kondratova AA, Gorbacheva VY, Gudkov AV, Antoch MP (2003) BMAL1-dependent circadian oscillation of nuclear CLOCK: posttranslational events induced by dimerization of transcriptional activators of the mammalian clock system. Genes Dev 17: 1921–1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri K, Vallone D, Gondi SB, Santoriello C, Dickmeis T, Foulkes NS (2005) Temperature regulates transcription in the zebrafish circadian clock. PloS Biol 3: 2005–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Loros J, Dunlap JC (2000) Phosphorylation of the Neurospora clock protein FREQUENCY determines its degradation rate and strongly influences the period length of the circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 234–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Haffter P, Nüsslein-Volhard C (1994) Large-scale mutagenesis in the zebrafish: in search of genes controlling development in a vertebrate. Curr Biol 4: 189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi E, Saini C, Bauer C, Laroche T, Naef F, Schibler U (2004) Circadian gene expression in individual fibroblasts: cell-autonomous and self-sustained oscillators pass time to daughter cells. Cell 119: 693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasevicius A, Ekker SC (2000) Effective targeted gene ‘knockdown' in zebrafish. Nat Genet 26: 216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plautz JD, Kaneko M, Hall JC, Kay SA (1997) Independent photoreceptive circadian clocks throughout Drosophila. Science 278: 1632–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MA, Kalderon D (2002) Proteolysis of the Hedgehog signalling effector Cubitus interruptus requires phosphorylation by Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 and Casein Kinase 1. Cell 108: 823–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reppert SM, Weaver DR (2001) Molecular analysis of mammalian circadian rhythms. Annu Rev Physiol 63: 647–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S, Ho RK, Herrmann BG, Nüsslein-Volhard C (1992) The protein product of the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T gene is expressed in nuclei of the germ ring and the notochord of the early embryo. Development 116: 1021–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman LP, Zylka MJ, Reppert SM, Weaver DR (1999) Expression of basic helix-loop-helix/PAS genes in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 89: 387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun ZS, Albrecht U, Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Eichele G, Lee CC (1997) RIGUI, a putative mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila period gene. Cell 90: 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai TK, Vardhanabhuti V, Foulkes NS, Whitmore D (2004) Early embryonic light detection improves survival. Curr Biol 14: R104–R105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai TK, Young LC, Whitmore D (2007) Light signaling to the zebrafish circadian clock by cryptochrome 1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 14712–14717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallone D, Gondi SB, Whitmore D, Foulkes NS (2004) E-box function in a period gene repressed by light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 4106–4111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier R, Besseau L, Boeuf G, Piparelli A, Gothilf Y, Gehring WG, Klein DC, Falcon J (2006) Starting the zebrafish pineal circadian clock with a single photic transition. Endocrinology 147: 2273–2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager-Smith K, Kay SA (2000) Circadian rhythm genetics: from flies to mice to humans. Nat Genet 26: 23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DK, Yoo S-H, Liu AC, Takahashi JS, Kay SA (2004) Bioluminescence imaging of individual fibroblasts reveals persistent, independently phased circadian rhythms of clock gene expression. Curr Biol 14: 2289–2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore D, Foulkes NS, Sassone-Corsi P (2000) Light acts directly on organs and cells in culture to set the vertebrate circadian clock. Nature 404: 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore D, Foulkes NS, Strahle U, Sassone-Corsi P (1998) Zebrafish Clock rhythmic expression reveals independent peripheral circadian oscillators. Nat Neurosci 1: 701–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SW, Easter SS (1991) Stereotyped pathway selection by growth cones of early epiphysial neurons in the embryonic zebrafish. Development 112: 723–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MW, Kay SA (2001) Time zones: A comparative genetics of circadian clocks. Nat Rev Genet 2: 702–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Sehgal A (2008) Probing the relative importance of molecular oscillations in the circadian clock. Genetics 178: 1147–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv L, Gothilf Y (2006) Circadian time-keeping during early stages of development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4146–4151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv L, Levkovitz S, Toyama R, Falcon J, Gothilf Y (2005) Functional development of the zebrafish pineal gland: light-induced expression of period2 is required for onset of the circadian clock. J Neuroendocrinol 17: 314–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]