Abstract

Background and objectives: An ideal and effective screening tool should perform equally across ethnic groups. The objective of this study was to determine whether the widely advocated creatinine-based estimated GFR (eGFR) threshold of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 identifies the typical metabolic abnormalities related to chronic kidney disease equally well in minority and nonminority adults.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: This objective was addressed using data for 8918 minority and nonminority adult participants in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 through 2006, which used stratified, multistage, probability sampling methods to assemble a nationwide probability sample of the noninstitutionalized population of the United States. Metabolic abnormalities including BP, potassium, hemoglobin, bicarbonate, uric acid, calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone were defined by fifth or 95th percentile values.

Results: Among participants with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, black individuals were more likely than white individuals to have low hemoglobin (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 3.76; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.94 to 7.28), elevated uric acid (aOR 2.15; 95% CI 1.26 to 3.68), and elevated parathyroid hormone (aOR 3.93; 95% CI 2.33 to 6.66).

Conclusions: Metabolic consequences of reduced eGFR are more common in black individuals and seem to be present at levels well above 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; thus, black individuals should be screened for the metabolic complications of chronic kidney at higher GFR levels.

Creatinine-based estimates of GFR (eGFR) are widely used to define chronic kidney disease (CKD), because they are believed to offer the combination of acceptable accuracy, convenience, and low cost (1–3). Current guidelines recommend that physicians begin screening for the metabolic disturbances of CKD once the creatinine-based eGFR reaches 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Recent data, however, suggest that a strategy of using this single eGFR threshold, 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, may disadvantage minority populations. Using the US Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III; 1988 through 1994) database, we found that a case definition of CKD with a single eGFR value of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 seemed to disadvantage minority populations, because metabolic abnormalities such as high BP, anemia, and elevated phosphorus and uric acid were already considerably more prevalent at higher eGFR values in black than in white participants (4). We believe that confirmation of these findings in a more recent, nationally representative population is of public health relevance, not least because of the changes in the demographic profile that have occurred since the conclusion of NHANES III (5). In addition, unlike more recent iterations of NHANES, parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels were not measured in NHANES III, preventing assessment of a classic metabolic complication of CKD. The objective of this study, therefore, was to determine whether a creatinine-based eGFR threshold of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, as calculated by the re-expressed Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study formula and the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) formula, identifies metabolic abnormalities equally well in minority and nonminority adult NHANES participants studied between 2003 and 2006 (n = 8918).

Materials and Methods

Design

NHANES 2003 through 2004 and NHANES 2005 through 2006 used stratified, multistage, probability sampling methods to assemble a nationwide probability sample of the noninstitutionalized population of the United States (6). Calibration factors can affect creatinine-based estimates of glomerular filtration, and NHANES 2003 through 2004 and 2005 through 2006 data have been directly calibrated with reference standards (3). All participants aged ≥20 yr were eligible for determination of hematologic and biochemical profiles at mobile examination centers.

Measurements and Definitions

As recommended by NHANES, the following formula was used to adjust the NHANES serum creatinine values in 2005 through 2006 to ensure comparability with standard creatinine: Standard creatinine (mg/dl) = −0.016 + 0.978 × (NHANES 2005 through 2006 uncalibrated serum creatinine [mg/dl]). No adjustment was needed for creatinine levels measured in 2003 through 2004 (7–9). eGFR levels were derived from the re-expressed MDRD Study formula, namely, 175 × (serum creatinine value)−1.154× age−0.203× 0.742 (if female) × 1.21 (if black) (10). An additional equation was used for black participants, the specific equation developed at the baseline evaluation for AASK, relating clearance of I125-iothalamate to serum creatinine, gender, and age: eGFR = 329 × creatinine − 1.096 × age − 0.294 × 0.736 (if female) (11). Because body mass index was higher for black individuals, we also used eGFR estimates, unadjusted for body surface area (BSA), by multiplying each patient's eGFR by BSA and dividing by 1.73 m2.

Metabolic abnormalities were defined by the fifth or 95th percentile of their respective distributions in the overall population. The specific threshold values were systolic BP ≥157.5 mmHg, diastolic BP ≥89.7 mmHg, potassium ≥4.5 mmol/L, hemoglobin ≤12.1 g/L, bicarbonate ≤20.5 mmol/L, uric acid ≥7.7 mg/dl, calcium ≤8.9 mg/dl, phosphorus ≥4.7 mg/dl, and PTH ≥81.5 pg/ml. PTH level was measured by the ECL/Origen electrochemiluminescent method, with a coefficient of variation <5% at all times (6). Self-reported diabetes was defined as an affirmative answer to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Self-reported hypertension was defined as an affirmative answer to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have hypertension, also called high BP?”

Statistical Analysis

χ2 analysis and ANOVA were used for unadjusted comparisons of baseline variables between ethnic groups. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to explore multivariate associations when abnormal values of metabolic and BP variables were considered as binary (yes/no) variables. National estimates of each parameter were adjusted for the sampling weights implicit in complex survey designs, using SUDAAN software (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) for complex sample surveys. SAS 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for data assembly. All data are presented as means ± SE unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Of the study population, 72.9% were white, 11.0% were black, 11.4% were Hispanic, and 4.7% were of other races (Table 1). Mean eGFR values were 82.9 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for white individuals, 97.4 for black individuals, 100.6 for Hispanic individuals, and 92.5 for other races (P < 0.0001). Proportions with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were 9.5% of white individuals, 5.4% of black individuals, 2.8% of Hispanic individuals, and 5.0% of other races (P < 0.0001). Body mass index was significantly higher for black individuals. Unadjusting the MDRD GFR estimate for BSA gave the same trend in proportions with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, white > black > Hispanic individuals. Compared with estimates that adjusted for BSA, the largest decrement in the proportion with eGFR <60 was for white individuals. The proportions for urinary albumin-creatinine ratio >30 mg/g were 8.0% of white individuals, 12.1% of black individuals, 10.9% of Hispanic individuals, and 13.3% of other races (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Population characteristics, compared by race/ethnicity (n = 8918)a

| Characteristic | Racial/Ethnic Groups

|

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | White | Black | Hispanic | Other | ||

| Race (%) | 100 | 72.9 (2.2) | 11.0 (1.3) | 11.4 (1.3) | 4.7 (0.4) | |

| GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 87.0 (0.6) | 82.9 (0.6) | 97.4 (0.9) | 100.6 (1.0) | 92.5 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (%) | 8.1 (0.5) | 9.5 (0.6) | 5.4 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) | 5.0 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| GFR (ml/min) | 96.0 (0.7) | 92.4 (0.7) | 110.4 (1.1) | 105.5 (1.1) | 94.8 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| <60 ml/min (%) | 6.5 (0.5) | 7.5 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 (<0.1) | 0.9 (<0.1) | 1.0 (<0.1) | 0.8 (<0.1) | 0.9 (<0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Urinary ACR (mg/g) | 28.7 (2.3) | 23.1 (2.1) | 58.6 (11.9) | 31.4 (5.0) | 39.0 (9.0) | 0.0067 |

| ≥30 (%) | 9.0 (0.4) | 8.0 (0.4) | 12.1 (1.0) | 10.9 (0.8) | 13.3 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Age (yr) | 46.6 (0.4) | 48.3 (0.5) | 43.8 (0.5) | 39.6 (0.5) | 43.5 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Female (%) | 51.7 (0.5) | 51.4 (0.6) | 55.1 (1.0) | 49.5 (1.0) | 53.6 (2.9) | 0.0053 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 (0.1) | 28.2 (0.2) | 30.4 (0.2) | 28.6 (0.2) | 26.2 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Born outside United States (%) | 15.1 (1.5) | 5.4 (0.9) | 8.9 (2.2) | 66.2 (3.1) | 56.7 (4.4) | <0.0001 |

| Self-reported diabetes (%) | 7.7 (0.4) | 7.0 (0.5) | 11.0 (0.6) | 8.9 (1.0) | 8.0 (1.3) | 0.0005 |

| Self reported hypertension (%) | 29.9 (0.9) | 31.2 (1.1) | 35.3 (1.1) | 17.9 (1.5) | 25.0 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Serum iron (mg/dl) | 86.7 (0.7) | 88.3 (0.7) | 75.0 (0.6) | 86.9 (1.1) | 88.7 (2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Red blood cell folate (mg/dl) | 292.7 (2.8) | 308.6 (3.7) | 230.2 (2.6) | 264.1 (4.9) | 264.3 (7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/ml) | 538.1 (8.9) | 513.0 (8.9) | 596.4 (30.9) | 647.2 (39.6) | 527.4 (18.0) | 0.0086 |

Column percentages are reported throughout. Numbers in parentheses represent SE. ANOVA and χ2 analysis, respectively, were used for between-group comparisons of continuous and categorical variables. ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; BMI, body mass index.

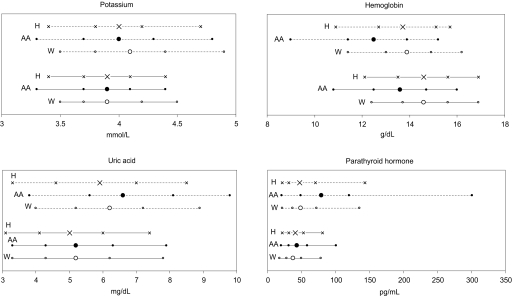

Table 2 compares mean levels of the clinical variables under scrutiny by race/ethnicity. For the overall population, differences between racial/ethnic groups were present for all variables except phosphorus; among individuals with eGFR <60 ml/min per .73 m2, differences were present for systolic BP, potassium, hemoglobin, uric acid, and PTH. Distribution of four CKD complications (abnormal potassium, hemoglobin, uric acid, and PTH levels) in white, Hispanic, and black individuals with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and in the overall population appear in Figure 1. Because of the need to incorporate sampling weights into the statistical computation, these data cannot be presented as classic distribution curves. These graphs demonstrate a higher likelihood of these complications among black individuals.

Table 2.

BP and laboratory variablesa

| Variable | Racial/Ethnic Groups

|

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | White | Black | Hispanic | Other | ||

| Overall population | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | <0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 122.9 (0.4) | 123.1 (0.4) | 126.3 (0.7) | 119.7 (0.7) | 121.3 (1.0) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 98.2, 157.5 | 98.0, 157.4 | 100.1, 165.1 | 97.6, 150.0 | 96.3, 160.4 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 0.0015 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 70.5 (0.2) | 70.5 (0.3) | 71.5 (0.5) | 69.3 (0.4) | 71.5 (0.8) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 51.4, 89.7 | 51.4, 89.5 | 51.4, 93.5 | 50.7, 89.4 | 52.8, 88.6 | |

| potassium (mmol/L) | <0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 4.0 (<0.1) | 4.0 (<0.1) | 3.9 (<0.1) | 3.9 (<0.1) | 3.9 (<0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 3.4, 4.5 | 3.5, 4.5 | 3.3, 4.4 | 3.4, 4.4 | 3.3, 4.4 | |

| hemoglobin (mg/dl) | <0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 14.5 (<0.1) | 14.6 (<0.1) | 13.6 (<0.1) | 14.6 (<0.1) | 14.3 (<0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 12.1, 16.8 | 12.4, 16.9 | 10.8, 16.0 | 12.1, 16.9 | 11.8, 16.4 | |

| bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 0.0002 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 24.8 (0.1) | 24.8 (0.1) | 24.9 (0.1) | 24.4 (0.1) | 24.9 (0.2) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 20.5, 27.7 | 20.6, 27.7 | 20.7, 27.9 | 20.2, 27.3 | 20.9, 27.9 | |

| uric acid (mg/dl) | <0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 5.4 (<0.1) | 5.4 (<0.1) | 5.4 (<0.1) | 5.1 (<0.1) | 5.5 (<0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 3.3, 7.7 | 3.3, 7.8 | 3.3, 7.9 | 3.1, 7.4 | 3.5, 7.7 | |

| calcium (mg/dl) | 0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 9.5 (<0.1) | 9.5 (<0.1) | 9.5 (<0.1) | 9.5 (<0.1) | 9.5 (<0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 8.9, 10.0 | 8.9, 10.0 | 8.9, 10.1 | 8.9, 10.0 | 8.8, 10.0 | |

| phosphorus (mg/dl) | 0.2639 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 3.8 (<0.1) | 3.8 (<0.1) | 3.8 (<0.1) | 3.8 (<0.1) | 3.8 (<0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 2.9, 4.7 | 2.9, 4.7 | 2.9, 4.7 | 2.9, 4.7 | 2.9, 4.7 | |

| PTH (pg/ml) | <0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 43.9 (0.5) | 42.5 (0.5) | 51.5 (1.3) | 45.3 (0.5) | 44.6 (1.6) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 18.4, 81.5 | 17.9, 78.3 | 19.9, 100.7 | 21.4, 80.9 | 20.6, 83.6 | |

| eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.0300 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 136.8 (1.1) | 135.9 (1.2) | 144.5 (2.8) | 137.1 (5.0) | 144.3 (5.2) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 101.7, 179.5 | 101.5, 177.0 | 102.0, 194.7 | 91.6, 186.6 | 111.3, - | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 0.2500 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 65.9 (0.6) | 65.7 (0.7) | 68.5 (2.2) | 69.6 (2.5) | 67.5 (2.0) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 39.3, 89.3 | 39.2, 88.9 | 15.1, 95.0 | 45.5, 87.2 | 52.2, 84.4 | |

| potassium (mmol/L) | 0.0092 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 4.2 (<0.1) | 4.2 (<0.1) | 4.0 (<0.1) | 4.1 (0.1) | 4.3 (0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 3.4, 4.9 | 3.5, 4.9 | 3.3, 4.8 | 3.4, 4.7 | 3.7, 4.9 | |

| hemoglobin (mg/dl) | <0.0001 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 13.8 (0.1) | 13.9 (0.1) | 12.6 (0.2) | 13.9 (0.2) | 13.5 (0.3) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 11.2, 16.2 | 11.4, 16.2 | 9.0, 15.2 | 10.9, 15.7 | 10.4, 16.2 | |

| bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 0.6700 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 24.9 (0.1) | 24.9 (0.1) | 24.8 (0.3) | 24.4 (0.4) | 25.2 (0.4) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 20.3, 28.5 | 20.3, 28.5 | 19.8, 28.8 | 20.1, 29.4 | 21.0, 27.9 | |

| uric acid (mg/dl) | 0.0200 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 6.4 (0.1) | 6.3 (0.1) | 6.9 (0.2) | 6.2 (0.3) | 6.4 (0.2) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 4.0, 9.0 | 4.0, 8.9 | 3.8, 9.8 | 3.3, 8.5 | 4.7, 8.5 | |

| calcium (mg/dl) | 0.1600 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 9.5 (<0.1) | 9.5 (<0.1) | 9.5 (0.1) | 9.8 (0.1) | 9.4 (0.1) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 8.9, 10.2 | 8.9, 10.2 | 8.6, 10.1 | 8.8, 10.8 | 8.7. 10.1 | |

| phosphorus (mg/dl) | 0.8500 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 3.9 (< 0.1) | 3.9 (<0.1) | 3.8 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.2) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 2.9, 4.8 | 2.9, 4.8 | 2.9, 5.0 | 2.9, 4.8 | – | |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 0.0097 | |||||

| mean (SE) | 65.7 (2.3) | 61.7 (2.1) | 117.9 (2.1) | 64.2 (7.4) | 54.6 (7.3) | |

| 5th, 95th percentile | 21.4, 146.2 | 21.5, 135.5 | 20.6, 301.5 | 21.5, 143.0 | 18.1, 123.4 | |

ANOVA was used for comparisons between groups. DBP, diastolic BP; eGFR, estimated GFR; SBP, systolic BP.

Figure 1.

Fifth, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentile values for potassium, hemoglobin, uric acid, and parathyroid hormone (PTH) in participants with estimated GFR (eGFR) <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (dashed lines, top) and in the overall population (solid lines, bottom). ○, white; •, black; ×, Hispanic. Larger symbols denote 50th percentiles. AA, African American; H, Hispanic; W, white.

Table 3 shows odds ratio (OR) for metabolic abnormalities associated with different racial/ethnic categories in the overall cohort and for patients with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. With covariate adjustment, black participants were more likely than white participants to have abnormal systolic BP, diastolic BP, hemoglobin, uric acid, and PTH levels and less likely to have high potassium levels. The analysis that was restricted to participants with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 showed that black participants were more likely to have abnormal hemoglobin, uric acid, and PTH levels.

Table 3.

Adjusted OR associated with race/ethnicity for BP and laboratory variables ≤5th or ≥95th percentilesa

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | Hispanic | Other | |

| Overall population (n = 8918) | |||

| SBP ≥157.7 mmHg | 1.73 (1.25 to 2.40) | 1.58 (1.07 to 2.34) | 1.94 (1.30 to 2.90) |

| P | 0.0020 | 0.0200 | 0.0020 |

| DBP≥89.7 mmHg | 1.52 (1.06 to 2.18) | 0.98 (0.68 to 1.41) | 0.83 (0.45 to 1.52) |

| P | 0.0200 | 0.9100 | 0.5300 |

| potassium ≥4.5 mmol/L | 0.72 (0.53 to 0.96) | 0.75 (0.51 to 1.10) | 0.80 (0.49 to 1.32) |

| P | 0.0200 | 0.1300 | 0.3600 |

| hemoglobin ≤12.1 g/dl | 5.16 (3.69 to 7.22) | 1.32 (0.82 to 2.13) | 1.68 (0.99 to 2.83) |

| P | < 0.0001 | 0.2300 | 0.0500 |

| bicarbonate ≤20.5 mmol/L | 0.62 (0.31 to 1.25) | 1.24 (0.61 to 2.49) | 0.90 (0.41 to 1.98) |

| P | 0.1700 | 0.5300 | 0.7900 |

| uric acid ≥7.7 mg/dl | 1.44 (1.12 to 1.84) | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.39) | 1.53 (0.87 to 2.68) |

| P | 0.0050 | 0.5700 | 0.1300 |

| calcium ≤8.9 mg/dl | 0.96 (0.68 to 1.37) | 1.22 (0.83 to 1.81) | 1.62 (0.99 to 2.67) |

| P | 0.8300 | 0.2900 | 0.0500 |

| phosphorus ≥4.7 mg/dl | 0.85 (0.65 to 1.12) | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.21) | 0.82 (0.42 to 1.59) |

| P | 0.2400 | 0.2600 | 0.5400 |

| PTH ≥81.5 pg/ml | 2.67 (1.82 to 3.92) | 1.63 (1.10 to 2.41) | 1.56 (0.84 to 2.87) |

| P | <0.0001 | 0.0100 | 0.1500 |

| eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n = 720) | |||

| SBP ≥157.7 mmHg | 1.59 (0.75 to 3.38) | 2.80 (1.07 to 7.34) | 2.86 (1.01 to 8.05) |

| P | 0.2100 | 0.0300 | 0.0400 |

| DBP ≥89.7 mmHg | 1.70 (0.67 to 4.34) | 0.45 (0.10 to 2.03) | 1.66 (0.28 to 9.73) |

| P | 0.2500 | 0.2800 | 0.5600 |

| potassium ≥4.5 mmol/L | 0.75 (0.41 to 1.39) | 1.05 (0.40 to 2.75) | 1.68 (0.48 to 5.88) |

| P | 0.3500 | 0.9200 | 0.4000 |

| hemoglobin ≤12.1 g/dl | 3.76 (1.94 to 7.28) | 0.95 (0.50 to 1.80) | 0.34 (0.05 to 2.19) |

| P | 0.0003 | 0.8700 | 0.2400 |

| bicarbonate ≤20.5 mmol/L | 1.51 (0.40 to 5.70) | 1.08 (0.20 to 5.78) | 1.08 (0.17 to 6.76) |

| P | 0.5300 | 0.9200 | 0.9300 |

| uric acid ≥7.7 mg/dl | 2.15 (1.26 to 3.68) | 1.09 (0.41 to 2.91) | 1.38 (0.44 to 4.28) |

| P | 0.0070 | 0.8500 | 0.5700 |

| calcium ≤8.9 mg/dl | 1.46 (0.48 to 4.48) | 0.87 (0.26 to 2.93) | 4.00 (1.16 to 13.88) |

| P | 0.4900 | 0.8100 | 0.0200 |

| phosphorus ≥4.7 mg/dl | 0.82 (0.38 to 1.81) | 0.56 (0.19 to 1.64) | 1.38 (0.40 to 4.79) |

| P | 0.6100 | 0.2800 | 0.5900 |

| PTH ≥81.5 pg/ml | 3.93 (2.33 to 6.66) | 1.22 (0.60 to 2.49) | 1.14 (0.36 to 3.65) |

| P | <0.0001 | 0.5700 | 0.8200 |

OR, odds ratio. White individuals are the reference category throughout. Race/ethnicity, age, gender, body mass index, born outside the United States, self-reported diabetes, self-reported hypertension, serum iron, and red blood cell folate were included as adjustment variables in all models.

Among black participants, correlation-regression analysis showed that GFR estimates were higher with the AASK equation than with the MDRD equation:

|

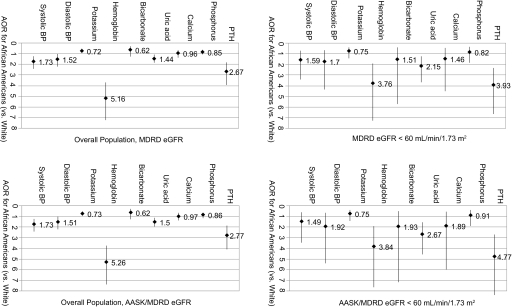

Whether the MDRD formula was used exclusively to adjust OR for metabolic abnormalities or the AASK formula was used for black participants, findings were similar with both strategies (Figure 2). Using either strategy without adjustment for BSA also yielded similar results (data not shown).

Figure 2.

In the top two panels, GFR was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study formula for both white and black participants. In the bottom two panels, GFR was estimated using the MDRD Study formula for white participants and the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) formula for black participants. White individuals are the reference category throughout. Race/ethnicity, age, gender, body mass index, born outside the United States, self-reported diabetes, self-reported hypertension, serum iron, and red blood cell folate were included as adjustment variables in all models; eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was used in analysis of the overall population. Variable values: Systolic BP ≥157.7 mmHg, diastolic BP ≥89.7 mmHg, potassium ≥4.5 mmol/L, hemoglobin ≤12.1 g/dl, bicarbonate ≤20.5 mmol/L, uric acid ≥7.7 mg/d L, calcium ≤8.9 mg/dl, phosphorus ≥4.7 mg/dl, PTH ≥81.5 pg/ml.

Discussion

In this nationally representative US sample, black individuals were more likely than white individuals to have CKD-associated metabolic abnormalities, both in the overall population and among participants with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. We found that black individuals had a lower prevalence of eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, mirroring recent findings from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study (12). The latter community-based study of adults aged ≥45 yr was designed to identify risk factors that contribute to excess mortality from stroke. Overall, the prevalence of eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was lower among black than white individuals, although black participants were more likely to have eGFR 10 to 19 ml/min per 1.73 m2. More recent findings indicate that risk for death is higher for black individuals with CKD than for white individuals with CKD (13). Individuals of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity now form the largest single minority population in the United States, and there is little reason to suspect that they should have intrinsically lower risk for kidney disease (5). One study suggested that rates of treated ESRD seem to be rising faster among Hispanic than non-Hispanic white individuals, for reasons yet to be clarified (14). In that study, Peralta et al., using data from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, demonstrated that Hispanic ethnicity was associated with a 93% excess risk for ESRD. Although the twin observations of a lower burden of earlier stage kidney disease and a higher burden of later stage kidney disease are perplexing, they suggest that race and ethnicity may be important considerations for screening for the presence and complications of CKD.

This study confirms findings seen in US adults almost 15 yr ago and adds hyperparathyroidism to the list of metabolic abnormalities showing racial disparity when a single eGFR threshold is used as a threshold for screening. The findings for PTH were notable, particularly because previous studies have suggested that secondary hyperparathyroidism should not be highly prevalent at eGFR values of >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (3).

A more recent analysis of this issue comes from Levin et al. (2), who studied an outpatient cohort that came mainly from primary care practices. The average eGFR in the cohort was 47 ± 17.7 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and PTH began to increase at an eGFR level of approximately 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Of interest, high PTH level was present in 12% of participants with eGFR >80 ml/min per 1.73 m2, compared with 56% of those with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. This study suggests that the eGFR threshold for stimulating PTH measurement may be higher than the firmly held level of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Regarding racial/ethnic differences in PTH, black individuals may possibly have intrinsically higher PTH levels than white individuals, irrespective of GFR. Several studies have shown that black individuals may have higher PTH levels and also larger parathyroid glands than white individuals, and similar findings have been reported among patients with ESRD (15–22). These findings cannot be entirely explained by differences in calcium intake and vitamin D status, and the possibility that skeletal resistance to PTH may be partly responsible has been suggested (23–25). Nevertheless, at least two lines of evidence suggest that hypovitaminosis D is common among black individuals and may be responsible for their higher PTH levels (26,27). Using NHANES III data, Martins et al. (27) demonstrated that 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels were lower in women and racial and ethnic minorities and in participants with diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. It is interesting that low levels of vitamin D were associated with hypertension, diabetes, and high triglyceride levels. The association between PTH and race was also reported by De Boer et al. (28), who studied 218 individuals with mean GFR estimates of 34 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and found that the mean adjusted PTH level was indeed higher in black individuals. Finally, it is tempting to speculate that the discrepancy between our study and older studies partly reflects sample size differences, referral population effects, and variability in the methods used to measure eGFR and PTH.

Unlike many other variables, we found lower potassium levels in black individuals, when adjustment was made for eGFR and other covariates. In this regard, it has been suggested that black individuals may be relatively potassium deficient compared with white individuals. For example, urinary potassium excretion seems to be lower, whether on random diets or those with fixed potassium contents (29–34). Another recent study showed lower 24-h urinary potassium excretion rates for black than white women (35). This finding has now been extended to men as well (36). Among participants in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) study, urinary potassium excretion was lower in black individuals, a phenomenon that persisted despite low potassium diet, suggesting that factors other than dietary intake are responsible. Given the reciprocal relationship between potassium deficiency and sodium retention, it has been suggested that variation in potassium handling may contribute to the higher than expected prevalence of hypertension among black individuals (37). The observation that black individuals were more likely to have a lower hemoglobin level is consistent with previous studies (38–41). Most recently, this racial difference in anemia prevalence has been linked to excess mortality in elderly black individuals (42).

Whether associations between serum creatinine and true GFR values differ in community-dwelling adults of different races and ethnicities and similar age and gender distribution (as they surely differ in black and Asian patients with CKD) cannot be determined from this analysis. Similarly, it is not possible to determine whether complications associated with declining eGFR develop at different eGFR levels or whether the higher prevalence of CKD-associated complications in minority groups with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 reflects a greater prevalence of these complications in general. This may be the case for PTH but not for others, irrespective of eGFR level. The data presented here would tend to support the latter hypothesis. For example, in this study, compared with white participants, black participants had higher adjusted OR for low hemoglobin levels, regardless of whether eGFR levels were <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, whether GFR was estimated using the MDRD Study formula or the AASK formula, or whether eGFR was unadjusted for BSA.

This study is limited by its cross-sectional nature. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether black individuals develop metabolic abnormalities at higher eGFR levels than white individuals or to determine whether our findings can be explained by a higher population burden of these abnormalities. In addition, we did not use gold-standard methods to estimate GFR; this being said, the estimate is commonly used in clinical practice and forms the basis of most sets of clinical practice guidelines. Despite its limitations, we believe that the study has useful features that may help inform clinical practice and public health policy design. The sampling strategy facilitates quantification of the burden and the complications of CKD in a nationally representative US sample. Our use of a 6-yr cycle of NHANES participants, with significantly increased numbers of participants in subgroups, strengthens these findings.

Conclusions

Overall, the study suggests that detection strategies for metabolic abnormalities based on a single “one size fits all” threshold eGFR value may delay identifying these complications in black individuals.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The data reported here were analyzed by the United States Renal Data System using public-use NHANES files. This study was performed as a deliverable under contract HHSN267200715002C (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

We thank United States Renal Data System colleagues Shane Nygaard and Beth Forrest for manuscript preparation and regulatory assistance and Nan Booth, MSW, MPH, for manuscript editing.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Clase CM, Kiberd BA, Garg AX: Relationship between glomerular filtration rate and the prevalence of metabolic abnormalities: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Nephron Clin Pract 105: c178–c184, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL: Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: Results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 71: 31–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, Hogg RJ, Perrone RD, Lau J, Eknoyan G: National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 139: 137–147, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley RN, Wang C, Ishani A, Collins AJ: NHANES III: Influence of race on GFR thresholds and detection of metabolic abnormalities. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2575–2582, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Census Bureau: United States Census 2000 Demographic profiles: 100-percent and sample data. Available at: http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/2002/demoprofiles.html. Accessed June 24, 2008

- 6.National Center for Health Statistics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. Accessed June 24, 2008

- 7.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004: Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies, 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/l40_c.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2008

- 8.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies, 2008. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_05_06/biopro_d.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2008

- 9.Coresh J, Astor BC, McQuillan G, Kusek J, Greene T, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Calibration and random variation of the serum creatinine assay as critical elements of using equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 920–929, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS: Assessing kidney function: Measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med 354: 2473–2483, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis J, Greene T, Appel L, Contreras G, Douglas J, Lash J, Toto R, Van Lente F, Wang X, Wright JT Jr: A comparison of iothalamate-GFR and serum creatinine-based outcomes: Acceleration in the rate of GFR decline in the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 3175–3183, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClellan W, Warnock DG, McClure L, Campbell RC, Newsome BB, Howard V, Cushman M, Howard G: Racial differences in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among participants in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Cohort Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1710–1715, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrotra R, Kermah D, Fried L, Adler S, Norris K: Racial differences in mortality among those with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1403–1410, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Fan D, Ordonez J, Lash JP, Chertow GM, Go AS: Risks for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular events, and death in Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2892–2899, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aloia JF, Vaswani A, Yeh JK, Flaster E: Risk for osteoporosis in black women. Calcif Tissue Int 59: 415–423, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell NH, Greene A, Epstein S, Oexmann MJ, Shaw S, Shary J: Evidence for alteration of the vitamin D-endocrine system in blacks. J Clin Invest 76: 470–473, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Finneran S, Rasmussen HM: Calcium absorption responses to calcitriol in black and white premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80: 3068–3072, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dufour DR, Wilkerson SY: Factors related to parathyroid weight in normal persons. Arch Pathol Lab Med 107: 167–172, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joffe BI, Seftel HC, Goldberg RC, Bersohn I, Hackeng WH: Metabolic bone disease in the elderly: Biochemical studies in three different racial groups living in South Africa. S Afr Med J 49: 965–966, 1975 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry HM III, Miller DK, Morley JE, Horowitz M, Kaiser FE, Perry HM Jr, Jensen J, Bentley J, Boyd S, Kraenzle D: A preliminary report of vitamin D and calcium metabolism in older African Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 41: 612–616, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perry HM III, Horowitz M, Morley JE, Fleming S, Jensen J, Caccione P, Miller DK, Kaiser FE, Sundarum M: Aging and bone metabolism in African American and Caucasian women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 1108–1117, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawaya BP, Butros R, Naqvi S, Geng Z, Mawad H, Friedler R, Fanti P, Monier-Faugere MC, Malluche HH: Differences in bone turnover and intact PTH levels between African American and Caucasian patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 64: 737–742, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris SS, Soteriades E, Coolidge JA, Mudgal S, Dawson-Hughes B: Vitamin D insufficiency and hyperparathyroidism in a low income, multiracial, elderly population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 4125–4130, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleerekoper M, Nelson DA, Peterson EL, Flynn MJ, Pawluszka AS, Jacobsen G, Wilson P: Reference data for bone mass, calciotropic hormones, and biochemical markers of bone remodeling in older (55–75) postmenopausal white and black women. J Bone Miner Res 9: 1267–1276, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bikle DD, Ettinger B, Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Tolan K: Differences in calcium metabolism between black and white men and women. Miner Electrolyte Metab 25: 178–184, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanoff LB, Parikh SJ, Spitalnik A, Benkinger B, Sebring NG, Slaughter P, McHugh T, Remaley AT, Yanovski JA: The prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and secondary hyperparathyroidism in obese Black Americans. Clin Endocrinol 64: 523–529, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins D, Wolf M, Pan D, Zadshir A, Tareen N, Thadhani R, Felsenfeld A, Levine B, Mehrotra R, Norris K: Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the United States: Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med 167: 1159–1165, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Boer IH, Gorodetskaya I, Young B, Hsu CY, Chertow GM: The severity of secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic renal insufficiency is GFR-dependent, race-dependent, and associated with cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2762–2769, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berenson GS, Voors AW, Dalferes ER Jr, Webber LS, Shuler SE: Creatinine clearance, electrolytes, and plasma renin activity related to the blood pressure of white and black children: The Bogalusa Heart Study. J Lab Clin Med 93: 535–548, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voors AW, Dalferes ER Jr, Frank GC, Aristimuno GG, Berenson GS: Relation between ingested potassium and sodium balance in young blacks and whites. Am J Clin Nutr 37: 583–594, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorof JM, Forman A, Cole N, Jemerin JM, Morris RC: Potassium intake and cardiovascular reactivity in children with risk factors for essential hypertension. J Pediatr 131: 87–94, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lasker N, Hopp L, Grossman S, Bamforth R, Aviv A: Race and sex differences in erythrocyte Na+, K+, and Na+-K+-adenosine triphosphatase. J Clin Invest 75: 1813–1820, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luft FC, Rankin LI, Bloch R, Weyman AE, Willis LR, Murray RH, Grim CE, Weinberger MH: Cardiovascular and humoral responses to extremes of sodium intake in normal black and white men. Circulation 60: 697–706, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallen IW, Rosa RM, Esparaz DY, Young JB, Robertson GL, Batlle D, Epstein FH, Landsberg L: On the mechanism of the effects of potassium restriction on blood pressure and renal sodium retention. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 19–27, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor EN, Curhan GC: Differences in 24-hour urine composition between black and white women. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 654–659, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turban S, Miller ER, Ange B, Appel LJ: Racial differences in urinary potassium excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1396–1402, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suh A, DeJesus E, Rosner K, Lerma E, Yu W, Young JB, Rosa RM: Racial differences in potassium disposal. Kidney Int 66: 1076–1081, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owen GM, Lubin AH, Garry PJ: Hemoglobin levels according to age, race, and transferrin saturation in preschool children of comparable socioeconomic status. J Pediatr 82: 850–851, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry GS, Byers T, Yip R, Margen S: Iron nutrition does not account for the hemoglobin differences between blacks and whites. J Nutr 122: 1417–1424, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan WH, Habicht JP: The non-iron-deficiency-related difference in hemoglobin concentration distribution between blacks and whites and between men and women. Am J Epidemiol 134: 1410–1416, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson-Spear MA, Yip R: Hemoglobin difference between black and white women with comparable iron status: Justification for race-specific anemia criteria. Am J Clin Nutr 60: 117–121, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denny SD, Kuchibhatla MN, Cohen HJ: Impact of anemia on mortality, cognition, and function in community-dwelling elderly. Am J Med 119: 327–334, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]