Abstract

Background and objectives: Despite emerging evidence that preemptive transplantation is the best treatment modality for patients reaching end-stage renal disease (ESRD), it is underutilized. Nephrologists’ views on preemptive transplantation are explored herein.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A web-based survey elicited barriers to preemptive transplantation as perceived by nephrologists as well as demographic and practice variables associated with a favorable attitude toward preemptive transplantation.

Results: Four hundred seventy-six of 5,901 eligible nephrologists responded (8% participation rate). Seventy-one percent of respondents agreed that preemptive transplantation is the best treatment modality for eligible chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients reaching ESRD, 69% reported that late referrals did not allow enough time for patients to be evaluated for preemptive transplantation, and 50% stated that there was too much delay between a patient's referral and the time the patient was seen at the transplant center. Nephrologists agreed to a lesser extent that they should be held accountable for CKD patients’ education (26%) and preemptive transplant referrals (23%). The most important patient factors considered when deciding not to discuss preemptive transplant were poor health status (70%), lack of compliance (69%), other medical problems (51%), being too old (40%), lack of prescription coverage (37%), and lack of health insurance to cover the costs of the procedure (36%).

Conclusions: Surveyed nephrologists consider preemptive transplantation as the optimal treatment modality for eligible patients. Late referral, patient health and insurance status, and delayed transplant center evaluation are perceived as major barriers to preemptive transplantation.

Approximately 11% of the adult population of the United States has chronic kidney disease (CKD) (1). This condition is generally progressive in nature and is a precursor to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Total Medicare ESRD costs for calendar year 2005 approached $21 billion, of which $6.96 billion was in-patient and $7.15 billion was out-patient. Physician/supplier costs accounted for another $4.1 billion. The rest was accounted for by skilled nursing, home health, and hospice (2).

The benefits of preemptive transplantation over transplantation after dialysis are emerging. Early studies reported comparable graft and patient survival for preemptive transplant patients and patients transplanted after dialysis (3,4). More recent studies show that preemptive transplantation is associated with better patient and graft survival (5–15). Additional advantages have been documented, such as avoidance of complications with dialysis access infections, reduced severity of sequelae of chronic kidney disease, increased ability to maintain employment, and decreased overall costs (16–18).

Despite the benefits of preemptive transplantation, this procedure is not widely adopted. In 2005, 2.3% of incident ESRD patients underwent preemptive transplantation, whereas the remaining patients started dialysis treatment (2). The progression from advanced CKD to dialysis, rather than to preemptive transplantation, can be attributed to a number of system and physician barriers such as late nephrology referral, UNOS requirements that creatinine clearance be <20 ml/min before a patient may be placed on the deceased donor kidney transplantation wait list, time to complete the medical evaluation for transplantation, or lack of timely availability of a kidney, whether from a deceased or live kidney donor (8,17–21). Uncertainty regarding the optimal level of impaired kidney function at which the transplant should be performed and the possibility that preemptive transplant patients’ adherence to immunosuppressive medications might be reduced compared with those who experience the hardships of dialysis therapy before transplantation also concern nephrologists (10).

Patient barriers might affect the adoption of preemptive transplantation. The majority of preemptive transplant patients receive their kidney from a live donor (10). Patients might encounter psychologic and attitudinal barriers when seeking a donor, similar to those experienced by patients on dialysis. Patients may be reluctant to ask relatives for a kidney and express concerns about the long-term consequences of donating a kidney (22–26). Patients with CKD who feel relatively well and are not burdened with dialysis may have less sense of urgency to pursue transplantation than those who are already established on dialysis (27).

Nephrologists are the primary source of information about modalities for kidney replacement therapy and refer potential kidney recipients to transplant centers (19). Thus, nephrologists are in a unique position to describe system and patients’ barriers that might affect the adoption of preemptive transplantation. The purpose of this study was to explore nephrologists’ views on preemptive transplantation, identify barriers to preemptive transplantation as perceived by nephrologists, and explore demographic and practice factors associated with nephrologists’ attitudes toward preemptive transplantation.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey of nephrologists practicing in the United States was implemented via the Internet. The sampling frame was the membership list of nephrologists for the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and the American Society of Nephrology (ASN). Duplicates were removed from the NKF listing so that nephrologists would be contacted only once. Nephrologists practicing abroad and those without a clinical practice were excluded to yield 5,911 U.S. nephrologists.

The investigators developed a questionnaire to assess attitudes. Items were generated based on information collected through a review of the published literature, a focus group interview with 10 nephrologists, and individual meetings and phone conversations with three nephrologists. A draft of the questionnaire was then pilot-tested for content and format. Participants included the nephrologists who participated to the individual or group interviews, four graduate students and two faculty members from the University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) with expertise in survey design, and two health educators working with ESRD patients. The questionnaire was revised according to the feedback received and was subsequently formatted for administration via the Internet. The Internet survey was sent to 30 nephrologists selected at random from the NKF membership list and six NKF Board members in addition to the UMB graduate students and faculty members who participated in the first pilot study. A form was included at the end of the pilot survey to inquire whether the invitation was persuasive, the formatting was user-friendly, and the questions were easy to understand. Based on the feedback received, two items were modified, one item was removed, and one item was added. The final questionnaire includes 24 attitudinal items along with items eliciting demographic and practice characteristics of the clinician.

The NKF and ASN e-mailed the Internet survey web link to eligible nephrologists. Follow-up of nonrespondents was implemented 10 days after initiation of the survey. To optimize participation, the Internet survey included an invitation from NKF or ASN emphasizing the importance of participating and the benefits to respondents and their patients (28). Nephrologists were informed that the confidentiality of data would be protected and that only aggregate results would be disseminated.

A descriptive analysis including frequencies for nominal variables and measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (SD) for ordinal or interval variables was performed. Fisher's exact test assessed nonrandom associations between attitudes toward preemptive transplantation and nephrologists or practice variables. Multivariate logistic regressions explored the association between nephrologists’ attitude toward preemptive transplantation (measured with the statement “compared with other treatment options, preemptive transplantation is the therapy of choice for eligible CKD patients reaching ESRD”) and demographic and practice characteristics.

Nephrologists were categorized into two groups, those physicians who agreed or tended to agree that preemptive transplantation was the best option for eligible patients (n = 423, 95%) and those who disagreed or tended to disagree with this statement (n = 24, 5%). The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.1. This study was exempted by the UMB Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of the 5,911 nephrologists contacted, one person could not be reached (undeliverable e-mail), one person was out of the office until after the closure of the survey, and eight persons replied that they did not have patient care responsibilities or that the survey was not relevant to them. Therefore, the total sampling frame included 5,901 nephrologists. A total of 476 responses were received—a response rate of 8%. Thirteen respondents who stated that they did not have any CKD patients were excluded from the analysis. Also excluded were two nephrologists who answered only the first question and one nephrologist who provided only sociodemographic information. As a result, the present report is based on the analysis of data obtained from 460 nephrologists.

The respondents’ mean age was 50 ± 10 yr. Characteristics of participants include 76% male, 94% board-certified, 87% exclusively adult practice, 66% urban areas, and 71% >10 yr of experience. Their primary job function was predominantly hospital- or private-practice-based (45% each). Half of the respondents had up to 100 CKD patients, and a third followed between 101 and 300 CKD patients. Participants reported following transplant patients but to a lesser extent than CKD patients. Forty-three percent stated that they needed two encounters to motivate patients to go to a transplant center for a preemptive transplant evaluation. Additional sociodemographic and practice characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating nephrologists

| Variable (n, %) unless otherwise specified | na | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| Mean ± SD | 50 ± 10 | |

| Range | 45 | |

| Gender (n = 419) | ||

| Male | 320 | 76 |

| Female | 99 | 24 |

| Board-certified nephrologists (n = 427) | ||

| Yes | 401 | 94 |

| No | 26 | 6 |

| Primary job function (n = 426) | ||

| Hospital-based nephrologist | 190 | 45 |

| Private practice nephrologist | 192 | 45 |

| Other | 44 | 10 |

| Location of practice (n = 424) | ||

| Urban area | 278 | 66 |

| Suburban area | 112 | 26 |

| Rural area | 34 | 8 |

| Years of experience (n = 425) | ||

| Up to 10 yr | 123 | 29 |

| More than 10 yr | 302 | 71 |

| CKD patients (n = 424) | ||

| 1-100 | 214 | 50 |

| 101-300 | 134 | 32 |

| >300 | 76 | 18 |

| Pediatric CKD patients (n = 417) | ||

| None | 363 | 87 |

| Up to 40% | 23 | 6 |

| More than 40% | 31 | 7 |

| Transplant patients (n = 426) | ||

| Less than 10 | 131 | 31 |

| 10-50 | 180 | 42 |

| >50 | 115 | 27 |

| African-American patients (n = 405) | ||

| Up to 55% | 327 | 81 |

| More than 55% | 78 | 19 |

| Number of encounters needed before patients contact a transplant center (n = 422) | ||

| 1 | 67 | 16 |

| 2 | 183 | 43 |

| 3 | 129 | 31 |

| 4 or more | 43 | 10 |

Total n per category not equal to 460 because of missing data.

Nephrologists’ General Views about Preemptive Transplantation

Surveyed nephrologists overwhelmingly agreed (71%) that preemptive transplantation is the best treatment modality for eligible patients who reach ESRD (Table 2). More than half of respondents agreed that patient care would improve with better communication between nephrologists and transplant surgeons before and after transplant surgery (respectively, 52% and 54%). They agreed to a lesser extent that nephrologists should be held accountable for CKD patients’ education (26%) and preemptive transplant referrals (23%). Finally, only 19% agreed that preemptive transplantation would increase the demand for deceased kidney donors.

Table 2.

Nephrologists’ general views on preemptive transplantation

| Agree

|

Tend to Agree

|

Tend to Disagree

|

Disagree

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Attitudes toward preemptive transplantationa | ||||||||

| Compared to other treatment options, preemptive transplantation is the therapy of choice for eligible CKD patients reaching ESRD | 319 | 71 | 104 | 23 | 14 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

| More formal communication between nephrologists and transplant surgeons post-transplant will improve patient care | 246 | 54 | 164 | 36 | 32 | 7 | 14 | 3 |

| More formal communication between nephrologists and transplant surgeons prior to transplant will improve patient care | 235 | 52 | 172 | 38 | 33 | 7 | 16 | 4 |

| Nephrologists should be held accountable for the proportion of CKD patients educated about preemptive transplantation | 118 | 26 | 177 | 40 | 86 | 19 | 65 | 15 |

| Nephrologists should be held accountable for the proportion of preemptive transplantation referrals | 105 | 23 | 156 | 35 | 110 | 25 | 76 | 17 |

| Promoting preemptive transplantation will increase the demand for deceased kidney donors | 84 | 19 | 118 | 27 | 151 | 34 | 92 | 21 |

| Financial impact on practicea | ||||||||

| Dialysis centers lose a source of revenue after referring patients for preemptive transplantation | 109 | 25 | 173 | 39 | 76 | 17 | 85 | 19 |

| The current reimbursement of nephrologists for post-transplant care negatively impacts rates of referral for preemptive transplantation | 69 | 16 | 108 | 25 | 152 | 35 | 108 | 25 |

| Nephrologists lose a source of revenue when they recommend preemptive transplantation | 60 | 13 | 143 | 32 | 120 | 27 | 122 | 27 |

| The current reimbursement for dialysis negatively impacts rates of referral for preemptive transplantation | 58 | 13 | 128 | 29 | 131 | 30 | 122 | 28 |

| Needs/issuesa | ||||||||

| There is a need for developing practice recommendations providing nephrologists with criteria for preemptive transplantation referrals | 210 | 47 | 191 | 42 | 38 | 8 | 11 | 2 |

| Nephrologists need additional information about the benefits of preemptive transplantation | 149 | 33 | 160 | 36 | 103 | 23 | 37 | 8 |

| Usually, patients eligible for preemptive transplantation are referred too late to a transplant center | 145 | 32 | 224 | 49 | 71 | 15 | 19 | 4 |

| Nephrologists need additional post-transplant care training with regard to immunosuppressant drug therapy | 143 | 32 | 200 | 45 | 86 | 19 | 20 | 4 |

| Nephrologists need additional post-transplant care training with regard to diabetes or infectious diseases management | 134 | 30 | 196 | 43 | 101 | 22 | 20 | 4 |

Total n per item not equal to 460 because of missing data.

The association of sociodemographic and practice characteristics was modeled on nephrologists’ view that preemptive transplantation was the best option for eligible CKD patients as shown in Table 3. Nephrologists who had been in practice for >10 yr were 59% less likely to have a positive attitude compared with those who had been practicing for 10 yr or less (odds ratio: 0.417; 95% confidence interval 0.239–0.726). In contrast, those who reported needing only one encounter to motivate their patients to have a transplant evaluation were 69% more likely to have a positive attitude compared with those needing more encounters (odds ratio: 1.686; 95% confidence interval: 1.064–2.673).

Table 3.

Odds of nephrologists considering preemptive transplantation as the best treatment modality for eligible CKD patientsa

| Characteristics (reference group) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Male (female) | 0.574 | 0.318, 1.034 |

| Board-certified nephrologists (not board-certified) | 1.027 | 0.409, 2.582 |

| Experience > 10 yr (experience ≤ 10 yr) | 0.417b | 0.239, 0.726 |

| Hospital practice (private practice) | 0.859 | 0.533, 1.384 |

| Practice in rural area (urban/suburban) | 1.288 | 0.526, 3.154 |

| Number of CKD patients >50 (≤50) | 1.158 | 0.651, 2.060 |

| Number of transplant patients >50 (≤50) | 1.705 | 0.996, 2.919 |

| Follows pediatric patients (no pediatric patients) | 1.197 | 0.543, 2.636 |

| Needs one encounter to motivate patient to pursue preemptive transplantation (needs more than one encounter) | 1.686b | 1.064, 2.673 |

CI, confidence interval.

P < 0.05.

With regard to the financial impact of preemptive transplantation on dialysis facilities or on nephrologists, 25% of respondents agreed that dialysis centers lose a source of revenue after referring patients for preemptive transplantation, and 13% agreed that recommending preemptive transplantation is detrimental to nephrologists from a financial perspective.

Almost half (47%) of surveyed nephrologists agreed that there was a need for developing preemptive transplantation practice recommendations, and an additional 42% tended to agree. They also agreed that there was a need for more information on the benefits of preemptive transplantation, along with additional training on immunosuppressive drug therapy and post-transplant management of diabetes and infectious diseases (33%, 32%, and 30%, respectively). Finally, the majority (81%) of respondents agreed or tended to agree that patients eligible for a preemptive transplant are usually referred too late to a transplant center.

Nephrologists’ Views about Preemptive Transplantation in Their Own Practice

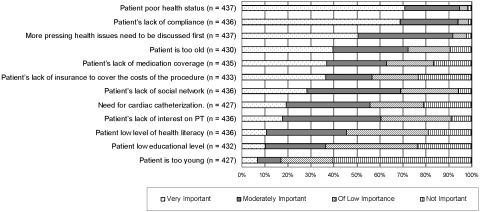

When asked about the importance of a number of factors that contribute to a delayed discussion about preemptive transplantation with their CKD patients, >70% of nephrologists reported poor health status as a very important factor. This was followed by lack of compliance (69%), other medical problems (51%), being too old (40%), lack of prescription coverage (37%), and lack of health insurance to cover the costs of the procedure (36%). Additional factors listed in Figure 1 were deemed less important by the nephrologists.

Figure 1.

Factors contributing to delayed discussion about preemptive kidney transplant.

The reasons most frequently reported by nephrologists for patients to delay transplantation were being uncomfortable talking with family or friends about donating a kidney (56%), having concerns about the consequences of a kidney removal on their donor health (54%), and needing time to adjust to the idea that their best treatment option is a preemptive transplant (54%). The cost of the transplant procedure for the patients or their donors, cost of immunosuppressive drugs, still feeling healthy, and not wanting their family or friends to know about the severity of their condition were raised to a lesser extent (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient and system barriers to preemptive transplantation

| Most of the Time

|

Half of the Time

|

Once in a While

|

Never

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Patients’ reasons for delaying the procedurea | ||||||||

| Worry about the consequences of a kidney removal on their donor health | 84 | 18 | 165 | 36 | 160 | 35 | 47 | 10 |

| Not sure how the costs of the transplant procedure will be covered | 77 | 17 | 143 | 31 | 172 | 38 | 64 | 14 |

| Not comfortable talking with family/friends about donating a kidney | 73 | 16 | 182 | 40 | 150 | 33 | 53 | 12 |

| Still feel healthy | 69 | 15 | 117 | 25 | 195 | 42 | 78 | 17 |

| Need time to adjust to the idea that their best treatment option is preemptive transplantation | 64 | 14 | 184 | 40 | 138 | 30 | 71 | 16 |

| Concerned about the financial costs of the procedure for their donor | 55 | 12 | 115 | 25 | 184 | 40 | 103 | 23 |

| Worry they might not be able to pay for their immunosuppressant drugs after the kidney transplant | 54 | 12 | 114 | 25 | 184 | 40 | 103 | 23 |

| Do not want their family/friends to know about the severity of their condition | 13 | 3 | 48 | 11 | 175 | 38 | 219 | 48 |

| CKD patients’ access to information about preemptive transplantationa | ||||||||

| If available, I would give my patients a CD or a videotape describing pros and cons of preemptive transplantation | 324 | 74 | 92 | 21 | 13 | 3 | 7 | 2 |

| When presenting different alternatives to my patients, it is easier to recommend preemptive transplantation than dialysis therapy | 158 | 36 | 143 | 33 | 115 | 26 | 22 | 5 |

| It is difficult to get my patients to attend educational programs/classes to learn about their treatment options | 94 | 22 | 192 | 44 | 123 | 28 | 27 | 6 |

| Lack of time prevents me from discussing in detail preemptive transplantation with my patients | 28 | 6 | 90 | 20 | 148 | 34 | 174 | 40 |

| Referrals issuesa | ||||||||

| CKD patients are referred in such an advanced state that there is not enough time to plan for preemptive transplantation | 85 | 20 | 213 | 49 | 138 | 32 | 5 | 1 |

| There is too much delay between the time I refer a patient for preemptive transplantation and the time this patient is seen at the transplant center | 81 | 18 | 145 | 33 | 145 | 33 | 65 | 15 |

| When I recommend preemptive transplantation to my patients they immediately contact a transplant center to pursue this option | 73 | 17 | 168 | 39 | 154 | 35 | 39 | 9 |

Total n per item not equal to 460 because of missing data.

Sixty-nine percent of the nephrologists stated that, more often than not, CKD patients were referred to them at an advanced stage. Fifty-six percent of the nephrologists also said that, once they recommend preemptive transplantation, half or most of the time their patients immediately contacted a transplant center to pursue this option. Unfortunately, just over half (51%) of the nephrologists also reported that excessive delay between a patient's referral and the time the patient was seen at the transplant center was an additional barrier to preemptive transplantation.

Most nephrologists (74%) stated that they would be willing to share educational materials on the risks and benefits associated with preemptive transplantation. Approximately two-thirds of the nephrologists reported that most of the time or approximately half of the time it was difficult to have their CKD patients attend educational programs to learn about their treatment options. On the other hand, 74% of nephrologists stated that time constraints rarely or never affected their ability to discuss preemptive transplantation with their patients. This response was further validated by the fact that all but 11 respondents declared that they personally initiated discussion about preemptive transplantation with their patients. Approximately two-thirds of respondents indicated that most of the time or about half of the time it was easier for them to recommend preemptive transplantation over dialysis.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore nephrologists’ views on preemptive transplantation. Overwhelmingly, surveyed nephrologists reported a favorable attitude toward preemptive transplantation, acknowledging that preemptive transplantation is the best treatment modality for eligible CKD patients. The number of years of practice and the number of encounters needed before a patient is evaluated were negatively associated with having a favorable attitude toward preemptive transplantation. The results are consistent with a survey that demonstrated that primary care physicians with >10 yr of practice were less likely to recognize CKD than their less experienced colleagues (29). It is likely that nephrologists in practice for several years have received limited information on preemptive transplantation during their medical training. Continuing medical education programs might help these nephrologists appreciate the benefits of preemptive transplantation.

Most participants initiated the discussion with their patients about the possibility of having a preemptive transplantation and stated that preemptive transplantation was usually easier to recommend than dialysis. The findings are relevant to a previous study indicating that nephrologists play a very important role at motivating patients to pursue preemptive transplantation (19). Surveyed nephrologists were less inclined to agree that they should be held accountable for the number of patients referred for preemptive transplantation. Other factors might influence whether a patient will be evaluated for a transplant, among them patients’ motivation to pursue a preemptive transplant. According to participants, the reasons most frequently raised by patients to delay preemptive transplantation were their reluctance to talk with family or friends about donating a kidney, their concerns about the health consequences of a kidney removal on their donor, and their concerns about financial costs related to transplantation and kidney removal. These barriers are similar to the barriers reported by hemodialysis patients when considering live donor kidney transplantation (22,26).

Needing time to adjust to the idea of preemptive transplantation and still feeling healthy, although not as widely reported, might need further attention. Because early referral to a transplant center is likely to increase the chance of a patient's receiving a preemptive transplant, it is crucial to shorten the time needed by patients to adjust to the idea of preemptive transplantation. This might be a challenging task given the silent nature of CKD. Patients might not experience any serious symptoms until they reach an advanced stage, and consequently they might not grasp the severity of their condition. Several educational strategies could be used to address this issue: present CKD patients with material depicting the deterioration of kidney function over time and showing them where they are; involve CKD patients in the monitoring of kidney function; or enlist the support of patients who received a preemptive transplant. A discussion of mortality data with CKD patients is also warranted, although nephrologists might be reluctant to tackle this sensitive topic (30). Additionally, because the majority of preemptive transplants are with kidneys from living donors, family members and/or potential donors must be informed about preemptive transplantation.

Unbalanced information about treatment options can also play a role in delaying access to preemptive transplantation. Two-thirds of respondents stated that commercial educational programs for CKD patients do not cover preemptive transplantation as extensively as other ESRD treatment modalities. This finding suggests that CKD patients might not be appropriately informed about their options.

The majority of surveyed nephrologists stated that late referrals did not allow enough time for their patients to be evaluated for a transplant before initiation of dialysis. The detrimental effects of late nephrology referral are well documented (19,31–35). There also is some evidence that primary care physicians are less likely than nephrologists to provide optimal care to CKD patients (29,36). There clearly is a need for enhanced coordination of care between primary care physicians and nephrologists. In addition, general practitioners need training on how to identify CKD patients and guidance about the optimal timing of referral to nephrologists.

Most respondents reported undue delay between a patient's referral and his or her evaluation for a transplant. To address this issue, transplants centers might consider prioritizing the evaluation of patients not yet on dialysis, especially if a living donor is available.

Surveyed nephrologists also acknowledged the need for practice guidelines to help assess patient selection and timing of referral to a transplant center. This finding is consistent with the fact that the optimal timing of referral to the transplant center and preemptive transplant surgery remain imprecisely defined in the literature. Approximately half of the respondents also agreed that improving communication between nephrologists and transplant center staff before and after the transplant would benefit patients. It is likely that such collaboration would facilitate transition of care of CKD and transplant patients (37). Transplant centers need to evaluate patients in a timely manner. They also can play an instrumental role in providing information about preemptive transplantation to CKD patients and their families.

This study has several limitations. First, because of the low response rate, the findings can not be generalized. Still, the response rate is similar to the response rate obtained in many physician Internet surveys (38–42). The fact that prenotification emails were not sent to eligible nephrologists might partially explain the low participation rate (28). There is also the possibility for selection bias, as nephrologists with an interest in preemptive transplantation may have been more likely to participate in this study. Second, the structured format of the questionnaire did not allow for a complete investigation of patients’ barriers. A qualitative study with CKD patients and their families might have captured other barriers or a different perspective. Third, the conflicting reports on the financial impact of preemptive transplantation on dialysis facilities and on nephrologists suggest that responses might have suffered from social desirability bias. This bias is minimized by the respondents’ awareness of the anonymous nature of the survey. Finally, this study reveals the favorable attitudes of nephrologists toward preemptive transplantation. Still, attitudes may not reflect actual practice to refer patients for preemptive transplant evaluation.

Further research should examine attitudes of nephrologists with high levels of referrals for preemptive transplant versus those with low preemptive referral rates. There also is a need to more precisely characterize the views of other stakeholders such as CKD patients along with preemptive transplant patients and their donors. It also would be worthwhile surveying primary care physicians and other specialty physicians to better understand how to optimize their referral practices to nephrologists. Finally, although the financial impact of preemptive transplantation on nephrologists’ practice did not seem to be a major issue, nephrologists acknowledged the potential financial disincentive of preemptive transplantation on dialysis centers. These conflicting positions warrant further exploration.

The proposed studies will inform the development of multifaceted interventions targeting patients and their physicians. These interventions should start as early as possible in the continuum of CKD care. Interventions educating general practitioners about appropriate timing of CKD patients’ referral to nephrologists should be developed. Other programs should address the information needs of nephrologists with regard to the benefits of preemptive transplantation, appropriate referral practices, and post-transplant care. Early educational interventions about preemptive transplantation targeting CKD patients and their families should be implemented. These programs also should facilitate discussions on kidney donation between patients and their families. Such strategies have proven successful at increasing ESRD patients’ access to LDKT (43,44). Interventions examining the impact of financial disincentives on access to preemptive transplantation should be considered. Currently, nephrologists receive higher reimbursements for dialysis care than for post-transplant care. The effect of a change in reimbursement from dialysis-based to office-based should be explored.

Conclusions

Most surveyed nephrologists considered preemptive transplantation as the optimal treatment modality for eligible CKD patients. Efforts should be made to further enhance the role of nephrologists in facilitating CKD patients’ access to preemptive transplantation. Higher rates of preemptive transplantation should decrease health consequences of dialysis, enhance the ability to maintain employment, and improve transplantation outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Kidney Foundation. The authors would like to thank the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology for deploying the survey to their members. The authors also would like to thank the nephrologists who participated in group and individual interviews as well as those who participated in the survey. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. LiAna Tschen, who collected background information for this article during her work as a pharmacy student.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 1–12, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Renal Data System: USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2007

- 3.Katz SM, Kerman RH, Golden D, Grevel J, Camel S, Lewis RM, Van Buren CT, Kahan BD: Preemptive transplantation—an analysis of benefits and hazards in 85 cases. Transplantation 51: 351–355, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmoud A, Said MH, Dawahra M, Hadj-Aissa A, Schell M, Faraj G, Long D, Parchoux B, Martin X, Cochat P: Outcome of preemptive renal transplantation and pretransplantation dialysis in children. Pediatr Nephrol 11: 537–541, 1997. (erratum appears in Pediatr Nephrol 11(6): 777, 1997) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B: Waiting time on dialysis as the strongest modifiable risk factor for renal transplant outcomes: A paired donor kidney analysis. Transplantation 74: 1377–1381, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier-Kriesche HU, Port FK, Ojo AO, Rudich SM, Hanson JA, Cibrik DM, Leichtman AB, Kaplan B: Effect of waiting time on renal transplant outcome. Kidney Int 58: 1311–1317, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roake JA, Cahill AP, Gray CM, Gray DW, Morris PJ: Preemptive cadaveric renal transplantation—clinical outcome. Transplantation 62: 1411–1416, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI: Dialysis prior to living donor kidney transplantation and rates of acute rejection. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 172–177, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI: Effect of the use or nonuse of long-term dialysis on the subsequent survival of renal transplants from living donors. N Engl J Med 344: 726–731, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Matas AJ, Ellison MD, Gill JS, Kausz AT: Preemptive kidney transplantation: The advantage and the advantaged. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1358–1364, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papalois VE, Moss A, Gillingham KJ, Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, Humar A: Pre-emptive transplants for patients with renal failure: An argument against waiting until dialysis. Transplantation 70: 625–631, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asderakis A, Augustine T, Dyer P, Short C, Campbell B, Parrott NR, Johnson RW: Pre-emptive kidney transplantation: The attractive alternative. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 1799–1803, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vats AN, Donaldson L, Fine RN, Chavers BM: Pretransplant dialysis status and outcome of renal transplantation in North American children: A NAPRTCS Study. North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. Transplantation 69: 1414–1419, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker BN, Rush SH, Dykstra DM, Becker YT, Port FK: Preemptive transplantation for patients with diabetes-related kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 166: 44–48, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matas AJ, Payne WD, Sutherland DE, Humar A, Gruessner RW, Kandaswamy R, Dunn DL, Gillingham KJ, Najarian JS: 2,500 living donor kidney transplants: A single-center experience. Ann Surg 234: 149–164, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada H, Seki T, Nonomura K, Chikaraishi T, Takeuchi I, Morita K, Usuki T, Watarai Y, Togashi M, Hirano T, Koyanagi T: Pre-emptive renal transplantation in children. Int J Urol 8: 205–211, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mange KC, Weir MR: Preemptive renal transplantation: Why not? Am J Transplant 3: 1336–1340, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiel G: Living kidney donor transplantation—new dimensions. Transpl Int 11(Suppl 1): S50–S56, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng FL, Mange KC: A comparison of persons who present for preemptive and nonpreemptive kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1050–1057, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levin A: Consequences of late referral on patient outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15(Suppl 3): 8–13, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weng FL, Joffe MM, Feldman HI, Mange KC: Rates of completion of the medical evaluation for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 734–745, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pradel FG, Limcangco MR, Mullins CD, Bartlett ST: Patients’ attitudes about living donor transplantation and living donor nephrectomy. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 849–858, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pradel FG, Mullins CD, Bartlett ST: Exploring donors’ and recipients’ attitudes about living donor kidney transplantation. Prog Transplant 13: 203–210, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray LR, Conrad NE, Bayley EW: Perceptions of kidney transplant by persons with end stage renal disease. ANNA J 26: 479–483, 1999. (erratum appears in ANNA J 26(6): 638, 1999) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burroughs TE, Waterman AD, Hong BA: One organ donation, three perspectives: Experiences of donors, recipients, and third parties with living kidney donation. Prog Transplant 13: 142–150, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC: Living donation decision making: Recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant 16: 17–23, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon EJ: Patients’ decisions for treatment of end-stage renal disease and their implications for access to transplantation. Soc Sci Med 53: 971–987, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillman DA: Mail and Internet Surveys: The Taylored Design Method, 2nd Ed., Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2006

- 29.Boulware LE, Troll MU, Jaar BG, Myers DI, Powe NR: Identification and referral of patients with progressive CKD: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 192–204, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon EJ, Sehgal AR: Patient-nephrologist discussions about kidney transplantation as a treatment option. Adv Ren Replace Ther 7: 177–183, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinchen KS, Sadler J, Fink N, Brookmeyer R, Klag MJ, Levey AS, Powe NR: The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med 137: 479–486, 2002. (see comment) (see summary for patients in Ann Intern Med 137(6): I24, 2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avorn J, Winkelmayer WC, Bohn RL, Levin R, Glynn RJ, Levy E, Owen W Jr.: Delayed nephrologist referral and inadequate vascular access in patients with advanced chronic kidney failure. J Clin Epidemiol 55: 711–716, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roderick P, Jones C, Drey N, Blakeley S, Webster P, Goddard J, Garland S, Bourton L, Mason J, Tomson C: Late referral for end-stage renal disease: A region-wide survey in the south west of England. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1252–1259, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jungers P, Massy ZA, Nguyen-Khoa T, Choukroun G, Robino C, Fakhouri F, Touam M, Nguyen AT, Grunfeld JP: Longer duration of predialysis nephrological care is associated with improved long-term survival of dialysis patients (see comment). Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 2357–2364, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Ayanian JZ: Late referral to a nephrologist reduces access to renal transplantation (see comment). Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1043–1049, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orlando LA, Owen WF, Matchar DB: Relationship between nephrologist care and progression of chronic kidney disease. N C Med J 68: 9–16, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howard AD: Long-term posttransplantation care: The expanding role of community nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 47: S111–S124, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braithwaite D, Emery J, De Lusignan S, Sutton S: Using the Internet to conduct surveys of health professionals: A valid alternative? (see comment). Fam Pract 20: 545–551, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HL, Benson DA, Stern SD, Gerber GS: Practice trends in the management of prostate disease by family practice physicians and general internists: An internet-based survey. Urology 59: 266–271, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HL, Gerber GS, Patel RV, Hollowell CMP, Bales GT: Practice patterns in the treatment of female urinary incontinence: A postal and internet survey. Urology 57: 45–48, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim HL, Hollowell CMP, Patel RV, Bales GT, Clayman RV, Gerber GS: Use of new technology in endourology and laparoscopy by american urologists: Internet and postal survey. Urology 56: 760–765, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hollowell CMP, Patel RV, Bales GT, Gerber GS: Internet and postal survey of endourologic practice patterns among American urologists. J Urol 163: 1779–1782, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Lin JK, Kaplan B, Howard RJ: Increasing live donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial of a home-based educational intervention. Am J Transplant 7: 394–401, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schweitzer EJ, Yoon S, Hart J, Anderson L, Barnes R, Evans D, Hartman K, Jaekels J, Johnson LB, Kuo PC, Hoehn-Saric E, Klassen DK, Weir MR, Bartlett ST: Increased living donor volunteer rates with a formal recipient family education program. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 739–745, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]