Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) in Japanese patients with Müllerian carcinoma having a therapeutic history of platinum-based chemotherapy.

Methods

Patients who were diagnosed with Müllerian carcinoma (epithelial ovarian carcinoma, primary carcinoma of fallopian tube and peritoneal carcinoma) by histological examination and had received the initial platinum-based chemotherapy were included in the study. The study drug was administered to the patients at 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks.

Results

Seventy-four patients were enrolled in the study. All patients had received platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line regimen and more than 90% of patients had also received taxanes. The overall response rate was 21.9% (95% confidence interval, 13.1–33.1%) and 38.4% of patients had stable disease. The median time to progression was 166 days. The major non-haematological toxicities were hand-foot syndrome (Grade 3; 16.2%) and stomatitis (Grade 3; 8.1%). Myelosuppression such as leukopenia (Grade 3; 52.7%, Grade 4; 6.8%), neutropenia (Grade 3; 31.1%, Grade 4; 36.5%) and decreased haemoglobin (Grade 3; 14.9%, Grade 4; 2.7%) were the most common haematological toxicities.

Conclusion

We confirmed that a 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks regimen of PLD was active in Japanese patients with Müllerian carcinoma having a therapeutic history of platinum-based chemotherapy and toxicity was manageable by dose modification of PLD or supportive care.

Key words: pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, Müllerian carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, hand-foot syndrome, chemo-gynaecology, chemo-phase I-II-III, gynaecology

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 8000 cases of ovarian cancer are newly diagnosed in Japan and more than 4000 women die of this disease (1). From an embryologic perspective, epithelial ovarian carcinoma, primary carcinoma of fallopian tube and peritoneal carcinoma are generally recognized as a similar disease group, which is known as Müllerian carcinoma. In patients with primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube and peritoneal carcinoma, the experience with chemotherapeutic agents is largely limited to case reports and small studies due to the rarity of disease type (2,3). However, the overall experience closely parallels that of ovarian cancer, so treatment of primary carcinoma of the fallopian tube and peritoneal carcinoma is conducted according to that of ovarian cancer (2,3).

Advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is a highly chemosensitive solid tumour with response rates to first-line chemotherapy of ∼80%. The majority of patients, however, eventually relapse and treatment with second-line agents becomes necessary. Furthermore, patients with recurrent ovarian cancer ultimately die of chemoresistant disease. Therefore, it is very important to recognize recurrent ovarian cancer therapy as palliative therapy and therapeutic agents are required to show efficacy as well as favourable toxicity profile. However, there are not many drugs approved in Japan for ovarian carcinoma, or recommended by the Japanese clinical practice guideline for as second-line treatment except platinum, taxane and irinotecan.

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) is a formulation of doxorubicin hydrochloride encapsulated in long circulating STEALTH® liposomes and formulated for intravenous administration. STEALTH® liposomes have liquid membranes coated with polyethylene glycol, which attracts water and renders resistance to mononuclear phagocytosis (4). The liposome's small diameter (∼100 nm) and their persistence in the circulation allow their penetration into altered and often compromised, leaky tumour vasculature with entry into the interstitial space in malignant tissues (5). Therefore, pegylated liposomes are suitable for prolonged delivery of doxorubicin and have a prolonged circulation time (6,7). At these tumour sites, the accumulating liposomes gradually break down, releasing doxorubicin to the surrounding tumour cells (8,9). PLD has been designed to enhance the efficacy and to reduce the toxicities of doxorubicin such as myelosuppression, alopecia and cardiotoxicity by altering the plasma pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of the drug.

Based on the data from the Phases II and III clinical trials in Europe and the USA, it is evident that PLD possesses promising activity and a favourable toxicity profile in the second-line treatment of ovarian cancer (10–15). Currently, PLD is provided as one of the standard treatment options in recurrent ovarian cancer treatment guidelines (16–18).

The result of the Phase I clinical trial in Japan was reported (19). In that study, recommended PLD dose was evaluated in 15 Japanese patients with solid tumours and resulted in 50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks. In addition, one partial response (PR) and one normalization of CA125 were observed among six ovarian cancer patients enrolled in that study, and further trials with Japanese ovarian cancer patients were encouraged.

Based on the result from a Phase I clinical trial in Japan, we conducted the Phase II clinical trial of PLD in patients with recurrent or relapsed Müllerian carcinoma (epithelial ovarian carcinoma, primary carcinoma of fallopian tube, peritoneal carcinoma) having a therapeutic history of platinum-based chemotherapy.

We conducted a multicentre, non-randomized, open-label study to evaluate efficacy and safety of a PLD 50 mg/m2 every 4-week regimen in Japanese patients with Müllerian carcinoma who had previously been treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

PATIENT AND METHODS

Study Design

This study was a multicentre non-randomized, open-label trial to evaluate efficacy and safety of PLD in Japanese patients with Müllerian carcinoma previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was the best overall response (response rate) and secondary endpoints included adverse events and adverse drug reactions (incidence, severity, seriousness and causality), time to response and duration of response. The final evaluation of the antitumour effect was performed by the independent radiological review committee. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each site. This study was conducted based on ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with Good Clinical Practice.

Patients

This study included patients who met all the following inclusion criteria: (i) having histological confirmation of Müllerian carcinoma (epithelial ovarian carcinoma, primary fallopian tube carcinoma and peritoneal carcinoma); (ii) receiving first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and who would receive PLD as a second-line therapy if time to progression was within 12 months from the date of final administration of platinum therapy, excluding patients whose best response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy was progressive disease (PD), or who received PLD as a third-line therapy; (iii) receiving 1 or 2 regimens with prior chemotherapy; (iv) having measurable lesions that conformed to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) criteria; (v) ECOG performance status (PS) grade of 0–2; (vi) adequate functions of principal organs, defined by white blood cell (WBC) counts 3.0 × 103–12.0 × 103/mm3, neutrophil counts not less than 1.5 × 103/mm3, haemoglobin not less than 9.0 g/dl, platelet count not less than 10.0 × 104/mm3, serum AST, ALT and AP not more than 2.5 times the institutional upper limit of normal, total bilirubin not more than the institutional upper limit of normal, serum creatinine not more than 1.5 times the institutional upper limit of normal, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) not less than 50%, electrocardiography (ECG) normal or minor change without symptoms that required any therapeutic intervention, and no evidence of cardiac disorder or Class I in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification; (vii) no colony stimulating factor (CSF) agent or blood transfusion received within 2 weeks before the date of blood tests for screening; (viii) no previous treatment with hormonal agents, oral antimetabolic or immunotherapeutic agents for at least 2 weeks, with nitrosourea or mitomycin C at least 6 weeks, or with surgical therapy, radiation therapy or other chemotherapy for 4 weeks or more; (ix) abilities to stay in hospital for 4 consecutive weeks from the initial administration of PLD; (x) survival expectancy 3 months or longer; (xi) 20–79 of age years at enrolment in the trial; and (xii) received an explanation of this trial from the physicians with written informed consent forms and other relevant information and freely provided informed consent before the trial.

Patients who met any of the following exclusion criteria were excluded from the trial: (i) requiring drainage of pericardial fluid; (ii) having experienced myocardial infarction or angina attack within 90 days before the start of trial; (iii) receiving prior therapy with anthracycline (total anthracycline dose of more than 250 mg/m2 as doxorubicin); and (iv) having known hypersensitivity to doxorubicin or any component of PLD.

Medication

PLD was intravenously administered to each subject at a dose of 50 mg/m2 as doxorubicin hydrochloride on Day 1 of each cycle, followed by a treatment-free interval of 28 days including Day 1. This was repeated for at least two cycles if the subject did not meet the withdrawal criteria. PLD was administered at a rate of 1.0 mg/min from the start of infusion to completion, using an infusion pump in consideration of risks of development of infusion-related reactions. PLD was used by diluting with 250 ml of 5% glucose injection for a dose of less than 90 mg as doxorubicin hydrochloride or with 500 ml for a dose of 90 mg or more as doxorubicin hydrochloride.

After administration, PLD would be discontinued in subjects who met any of the following withdrawal criteria: (i) desiring to discontinue the study treatment or withdrawing consent; (ii) having LVEF decreased to less than 45% after administration of PLD or decreased by 20% or more than baseline; (iii) having no possibility for a subsequent cycle to be started within 6 weeks from the planned injection date because of adverse reactions or after 8 weeks for hand-foot syndrome (HFS) or stomatitis; (iv) having bilirubin increased to 3.0 mg/dl or more; (v) requiring a repeated reduction in the dose; (vi) the anticipated total dose of anthracycline antibiotics including PLD would exceed 500 mg/m2 as doxorubicin hydrochloride (including doses from prior chemotherapy and pre/postoperative treatment); (vii) being judged by the physician to have difficulties continuing the trial due to serious (or significant) adverse events; (viii) being assessed to have difficulty continuing the trial due to concurrent illnesses (e.g. complications); (ix) having obvious progression of the underlying disease or development of new lesions (PD); (x) having any of the exclusion criteria which was discovered after enrolment; and (xi) being judged as unfavourable to continue the trial by the physician.

Prior to administration of the study drug in the next cycle, all the subjects were confirmed to meet all the following criteria: (i) HFS or stomatitis ≤Grade 1; (ii) neutrophil counts ≥1.5 × 103/mm3; (iii) WBC counts ≥3.0 × 103/mm3; (iv) platelet counts ≥7.5 × 104/mm3; (v) bilirubin ≤1.5 mg/dl; and (vi) other adverse drug reactions ≤ Grade 2 (excluding fatigue, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia and lymphopenia). If any of these criteria was not met, the scheduled administration of the study drug for the next cycle would be delayed for 2 weeks at the maximum. If any of the above criteria was still not met after a 2-week delay from the scheduled initial date of each cycle, the trial for the subjects would be discontinued. In case Grade 2 HFS or stomatitis was observed at 6 weeks from the initial date of each cycle, the scheduled administration of the test drug for the next cycle would be delayed for 2 weeks. As a result, when the subjects met all the above criteria, the next cycle would be started. Even if the subjects met all the criteria, the scheduled initial date could be delayed for a maximum of 2 weeks at the investigator's discretion.

As the subjects met any of the following dose reduction criteria, the previous dose would be reduced by 25% (37.5 mg/m2) for the next cycle: (i) HFS or stomatitis ≥ Grade 3; (ii) neutrophil count <500/mm3 or WBC count <1000/mm3 that was maintained for at least 7 days; (iii) neutrophil counts <1000/mm3 with 38.0°C or higher fever; (iv) platelet reduction <2.5 × 104/mm3; (v) other adverse drug reactions ≥ Grade 3 (excluding fatigue, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, lymphopenia and other adverse events associated with infusion-related reactions); and (vi) the physician judged that the dose should be decreased. Dose reduction was permitted only once, and it was prohibited to increase the dose after the dose was reduced. If a further dose reduction was required after the dose was reduced, the trial for the subject would be discontinued.

Administration of CSF was admitted when patients met any of the following criteria: (i) neutrophil counts <1000/mm3 with fever (≥38°C); (ii) neutrophil counts <500/mm3; (iii) experience of either (i) or (ii) in the prior cycle and neutrophil counts <1000/mm3 in the following cycle.

Evaluation of Response and Safety

Tumour response evaluation was performed according to the RECIST guidelines. Confirmed duration of stable disease (SD) was defined as the duration of 8 consecutive weeks or longer after the start of administration.

Severity of adverse events was assessed according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 3.0.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

Among the subjects enrolled in this trial, those who received platinum-based chemotherapy as the first-line chemotherapy and experienced disease progression between 6 and 12 months after the completion of the platinum regimen were classified as the platinum-sensitive group, and those who had progression during the first-line chemotherapy, received platinum-based chemotherapy as the first-line chemotherapy and experienced progression less than 6 months after the completion of the platinum regimen, or who would receive PLD as a third-line therapy were classified as the platinum-resistant group. A sample size to produce the expected response rate of 30 and 15% for the platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant groups, respectively, with the threshold response rate of 5%, a significance level of 5% and power of 80% was determined to be 80 patients in total (20 and 60 patients for the platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant groups, respectively).

For the response evaluation, statistical analysis was performed based on the evaluation for the full analysis set (FAS) by the independent radiological review committee. The primary endpoint was the response rate, the proportion of patients with complete response (CR) or PR in the response analysis set, and the point estimate and two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The secondary endpoints included the duration of overall response, time to response and time to progression, and the progression-free survival was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and descriptive statistics (median, minimum and maximum) were calculated. The safety of PLD was evaluated for all the subjects treated with PLD. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS System for Windows release 8.02.

RESULT

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Seventy-four patients were enrolled into the trial between January and December 2005, and 73 patients (11 for the platinum-sensitive group and 62 for the platinum-resistant group), excluding one patient who was confirmed to be ineligible after enrolment, were eligible for the trial, and defined as the FAS. All 74 patients who received PLD were defined as the safety analysis set. Although the targeted number of patients for the platinum-sensitive group was 20, only 11 patients were enrolled. That was because the study was closed at the end of 2005 when the patient enrolment in the platinum-resistant group reached the target number due to slow enrolment.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | Total (n = 74) | Platinum sensitive (n = 11) | Platinum resistant (n = 63) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Median (range) | 57.0 (32–76) | 55.0 (40–72) | 58.0 (32–76) |

| Primary cancer (%) | |||

| Epithelial ovarian carcinoma | 62 (83.8) | 11 (100.0) | 51 (81.0) |

| Peritoneal carcinoma | 12 (16.2) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (19.0) |

| Tumour histology (%) | |||

| Serous | 49 (66.2) | 6 (54.5) | 43 (68.3) |

| Endometrioid | 8 (10.8) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (7.9) |

| Clear cell | 8 (10.8) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (11.1) |

| Mucinous | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| Other | 8 (10.8) | 1 (9.1) | 7 (11.1) |

| Initial FIGO stage (%) | |||

| I | 7 (9.5) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (9.5) |

| II | 1 (1.4) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| III | 50 (67.6) | 6 (54.5) | 44 (69.8) |

| IV | 16 (21.6) | 3 (27.3) | 13 (20.6) |

| Previous chemotherapy (%) | |||

| 1 regimen | 23 (31.1) | 11 (100.0) | 12 (19.0) |

| 2 regimen | 50 (67.6) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (79.4) |

| 3 regimen | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) |

| Previous chemotherapy with antracycline (%) | |||

| Yes | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| No | 71 (95.9) | 11 (100.0) | 60 (95.2) |

| Platinum-free interval (days) | |||

| Median (range) | 263 (28–2792) | 315 (216–441) | 235 (28–2792) |

| CA-125 at baseline (U/ml) | |||

| Median (range) | 243.6 (5.8–7809.8) | 192.1 (22.2–808.0) | 261.0 (5.8–7809.8) |

FIGO, Federation Internationale de Gynecologie et d'Obstetrique.

The median of patients' age was 57.0 years (range, 32–76). Among 74 patients enrolled, 62 had epithelial ovarian carcinoma and 12 had peritoneal carcinoma. Histological, 49 patients had serous carcinoma, eight had endometrioid carcinoma, eight had clear cell carcinoma, one had mucinous carcinoma and eight had other types of carcinoma. All 74 patients had received first-line chemotherapy including platinum regimen, 70 (94.6%) had also received taxanes as the first-line chemotherapy, and only three had received anthracycline in the prior chemotherapy. A total of 334 cycles of PLD was administered to 74 patients, and the median number of cycles administered was 4.0 (range, 1–10 cycles). Administration of PLD was completed or discontinued in all 74 patients before statistical analysis. The dose of PLD was reduced to 37.5 mg/m2 in 26 of 74 patients (35.1%). The scheduled administration of PLD was delayed in 49 of 74 patients (66.2%) and in 154 of 334 cycles (46.1%).

Response

The antitumour effect (best overall response) and response rate are shown in Table 2. The best overall response in 73 patients of FAS was CR in two patients, PR in 14, SD in 28, PD in 27 and not evaluable (NE) in two patients. The response rate was 21.9% (16 of 73) (95% CI: 13.1–33.1%). The response rate (two-sided 95% CI) by patient group was 27.3% (3 of 11) (95% CI: 6.0–61.0%) in the platinum-sensitive group and 21.0% (13 of 62) (95% CI: 11.7–33.2%) in the platinum-resistant group. The proportion of patients with CR, PR or SD was 60.3% (44 of 73) in FAS, and 54.5% (6 of 11) in the platinum-sensitive group and 61.3% (38 of 62) in the platinum-resistant group.

Table 2.

Response rate

| Total | Platinum sensitive | Platinum resistant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 73 | 11 | 62 |

| Best overall response: n (%) | |||

| CR | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.2) |

| PR | 14 (19.2) | 3 (27.3) | 11 (17.7) |

| SD | 28 (38.4) | 3 (27.3) | 25 (40.3) |

| PD | 27 (37.0) | 4 (36.4) | 23 (37.1) |

| NE | 2 (2.7) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (1.6) |

| Response rate | |||

| n (%) (95% CI) | 16 (21.9) (13.1–33.1) | 3 (27.3) (6.0–61.0) | 13 (21.0) (11.7–33.2) |

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progression disease; NE, not evaluable; 95% CI, confidence interval.

The results from subgroup analysis sets by platinum-free interval were as follows. In a subgroup analysis set where patients received PLD as a second-line therapy, the response rate by platinum-free intervals was 8.3% (1 of 12) and 27.3% (3 of 11) in patients with the platinum-free interval of within 6 months and of 6–12 months, respectively. In another subgroup analysis set where patients received PLD as a third-line therapy, the response rate was 7.1% (1 of 14), 15.4% (2 of 13) and 36.8% (7 of 19) in patients with the platinum-free interval of within 6 months, of 6–12 months and more than 12 months, respectively.

The response rate by histological type was 29.2% (14 of 48) and 25.0% (2 of 8) in patients with serous carcinoma and with endometrioid carcinoma, respectively. In patients with clear cell carcinoma, SD was observed in two of eight patients, and the time to progression in the two patients was 350+ and 87+ days, respectively. In patients with mucinous carcinoma, SD was observed in one of one patient and the time to progression was 135+ days.

The median and range of the duration of response, time to response and time to progression are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Time to response, duration of response and time to progression

| Total | Platinum sensitive | Platinum resistant | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 73 | 11 | 62 |

| Time to response (day) | |||

| Patient (%)a | 16 (21.9) | 3 (27.3) | 13 (21.0) |

| Median (range) | 54.0 (20–162) | 56.0 (54–59) | 52.0 (20–162) |

| Duration of response (day) | |||

| Patient (%)a | 16 (21.9) | 3 (27.3) | 13 (21.0) |

| Median (range) | 149.0 (56–309) | − (92–159) | 149.0 (56–309) |

| Withdrawal (%) | 11 (68.8) | 2 (66.7) | 9 (69.2) |

| Time to progression (day) | |||

| Patient (%)b | 71 (97.3) | 10 (90.9) | 61 (98.4) |

| Median (range) | 166.0 (14–358) | 159.0 (16–217) | 168.0 (14–358) |

| Withdrawal (%) | 30 (42.3) | 4 (40.0) | 26 (42.6) |

aResponder only. bExcluded two patients due to unable calculation for time to progression.

The median time to response (CR or PR) was 54.0 days. The median time to response was 56.0 days in the platinum-sensitive group and 52.0 days in the platinum-resistant group.

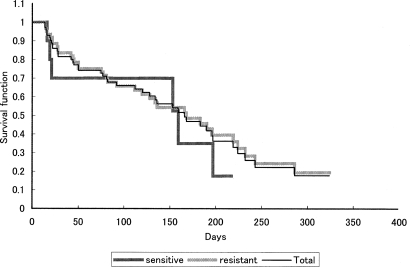

The median duration of overall response was 149.0 days. The median duration of overall response in the platinum-resistant group was 149.0 days, however, that in the platinum-sensitive group could not be calculated. The Kaplan–Meier curve for time to progression is shown in Fig. 1. The median time to progression was 166.0 days: 159.0 days in the platinum-sensitive group and 168.0 days in the platinum-resistant group. The median survival could not be calculated.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to progression.

Safety

Adverse drug reactions were reported from all 74 patients treated with PLD. The major adverse drug reactions observed in the study are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Grades 3 and 4 adverse drug reactions

| Adverse Reaction (MedDRA/J Ver9.0) | Number of patients (n = 74) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (%) | Grade 2 (%) | Grade 3 (%) | Grade 4 (%) | |

| Neutropenia | 8 (10.8) | 11 (14.9) | 23 (31.1) | 27 (36.5) |

| Lymphocytopenia | 15 (20.3) | 16 (21.6) | 29 (39.2) | 6 (8.1) |

| Leukopenia | 5 (6.8) | 20 (27.0) | 39 (52.7) | 5 (6.8) |

| Haemoglobin decreased | 23 (31.1) | 27 (36.5) | 11 (14.9) | 2 (2.7) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 27 (36.5) | 13 (17.6) | 4 (5.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Hand-foot syndrome | 20 (27.0) | 26 (35.1) | 12 (16.2) | 0 (0) |

| Stomatitis | 29 (39.2) | 22 (29.7) | 6 (8.1) | 0 (0) |

| Erythropenia | 42 (56.8) | 11 (14.9) | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea | 37 (50.0) | 6 (8.1) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| ALT (GPT) increased | 16 (21.6) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| Blood potassium decreased | 10 (13.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| Rash | 17 (23.0) | 19 (25.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Fatigue | 28 (37.8) | 5 (6.8) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 11 (14.9) | 5 (6.8) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| γ-GTP increased | 13 (17.6) | 4 (5.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhoea | 12 (16.2) | 4 (5.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| AST (GOT) increased | 18 (24.3) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Blood sodium decreased | 15 (20.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Small intestinal obstruction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Herpes zoster | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Glucose tolerance impaired | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

The most common Grade 3 or 4 adverse reactions were due to haematological toxicity: neutropenia in 50 patients (67.6%), leukopenia in 44 (52.7%), lymphopenia in 35 (47.3%), decreased haemoglobin in 13 (17.6%), thrombocytopenia in five (6.8%) and erythropenia in three patients (4.1%). The median time to nadir for neutrophils, WBCs, haemoglobin and platelets from the start of administration in the first cycle was 21.0 days, 21.0, 15.0 and 22.0 days, respectively. The median time to recovery to the level at which the administration of PLD in the next cycle was permitted was 7.0–8.0 days for any haematological event.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse drug reactions due to non-haematological toxicity included: HFS in 12 patients (16.2%), stomatitis in six (8.1%), febrile neutropenia, nausea, ALT (GPT) increased and blood potassium decreased in two each (2.7%) and deep venous thrombosis rash, herpes zoster, infection, upper respiratory tract infection, impaired glucose tolerance, diarrhoea, small intestinal obstruction, vomiting, fatigue, AST (GOT) increased, decreased blood sodium and increased γ-GTP in one each (1.4%). Only deep venous thrombosis was Grade 4. The median time to occurrence of HFS, rash and stomatitis from the start of administration was 34.0 days (2.0 cycles), 33.0 days (2.0 cycles) and 16.0 days (1.0 cycle), respectively. The median time to the Grade 2, 3 or 4 adverse reactions (Grade 3 or 4 for rash), which required delay of next administration, was 64.5 (3.0 cycles), 84.0 (3.0 cycles) and 43.0 (2.0 cycles), respectively and the median duration for those reactions was 15.0, 8.0 and 8.0 days, respectively.

Infusion-related reactions were seen in 14 patients (18.9%) only during the first cycle. Serious reactions were not seen. Of these patients, one patient had Grade 2 events and other patients had Grade 1 events. Symptoms associated with infusion-related reactions included hot flushes, facial flushing and hot feeling. These symptoms were restored on the day of occurrence or the following day. PLD was discontinued in one patient who had nausea, low back pain, chest tightness and facial flushing as Grade 2 infusion-related reactions. These symptoms were rapidly restored by supportive care with drip infusion of physiological saline. Although slowdown in the PLD infusion rate was required in two patients, the other 11 patients completed the infusion without any intervention. Among 14 patients with infusion-related reactions, 11 patients received the next cycle without recurrence of infusion-related reactions.

Cardiac toxicity was seen in 17 of 74 patients (23.0%), all of which were Grade 1. Increase in the incidence of cardiac toxicity associated with accumulation of PLD was not observed. Alopecia was seen in 18 patients (24.3%), which was Grade 1 in all of them.

There was no death due to adverse events reported during the trial period. Fourteen serious adverse reactions were seen in 11 patients (14.9%): two events each of nausea, HFS, small intestinal obstruction and stomatitis; and one event each of neutropenia, leukopenia, vomiting, pneumonitis, deep venous thrombosis and anorexia.

PLD was discontinued due to adverse reactions in 16 (21.6%). Common adverse reactions that required the discontinuation of PLD included: decreased haemoglobin in six patients (8.1%), leukopenia in four (5.4%) and HFS and neutropenia in three each (4.1%). The PLD dose was reduced in 24 patients (32.4%) due to adverse drug reactions such as HFS in 10 patients (13.5%), decreased haemoglobin and stomatitis in five each (6.8%) and neutropenia in three patients (4.1%). Administration of PLD was delayed in 49 patients (66.2%) in 111 cycles of 334 cycles due to adverse reactions mainly including leukopenia in 68 cycles (20.4%), neutropenia in 56 cycles (16.8%), HFS in 40 cycles (12.0%) and stomatitis in eight cycles (2.4%).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the efficacy and safety of PLD in Japanese patients with Müllerian carcinoma (epithelial ovarian carcinoma, primary fallopian tube carcinoma and peritoneal carcinoma) previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy.

Currently, platinum and taxane therapies are used for the standard first-line chemotherapy for treatment of ovarian carcinoma, though the results of Phase III clinical trials conducted in the US and Europe demonstrated the effectiveness of PLD, gemcitabine and topotecan in patients resistant to these drugs (13,14,20). However, these drugs have not been approved and the results from prospective studies of their use in patients with ovarian carcinoma previously treated with platinum and taxane therapy have not been reported in Japan. Our study was intended to provide the outcome in patients who had recurrent Müllerian carcinoma after the standard first-line chemotherapy (90% of patients in our study had received first-line chemotherapy with platinum and taxane).

In this trial, the response rate was 21.9% (95% CI: 13.1–33.1%) for all patients in FAS. The response rate in the platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant groups was 27.3% (95% CI: 6.0–61.0%) and 21.0% (95% CI: 11.7–33.2%), respectively. Better response was obtained in patients with longer platinum-free interval when PLD was administered as second- or third-line chemotherapy. Clinical studies conducted in the US and Europe showed that the response rate of PLD was 28.4% in the platinum-sensitive group and 6.5–18.3% in the platinum-resistant group (11,12,13). These response rates were similar to those obtained in our trial.

Common adverse reactions reported in this study were haematological toxicities (leukopenia, neutropenia and decreased haemoglobin), HFS and stomatitis.

The median time to nadir for WBC, neutrophils and haemoglobin after the start of administration of PLD was 15–22 days, and the median time to recovery to baseline after reaching the nadir was 7–8 days. Repeated cycles did not lead to worsening the events. Most patients could receive PLD continually by concomitant use of G-CSF and dose modification, such as dose reduction and delay of next administration.

In the previous Phase III study (13), HFS and stomatitis occurred in 49% (Grade 3 or higher: 23%) and 40% (Grade 3 or higher: 8%) of patients, respectively. Although these toxicities were seen in 78.3 and 77.0% of patients in our study, only 16.2 and 8.1% of patients experienced Grade 3 or higher toxicities, respectively. Most patients could continually receive PLD treatment by dose modification of PLD and supportive care, and the patients discontinued due to toxicities were few.

Infusion-related reaction that is known as toxicity specific to PLD was seen in 14 patients (18.9%) during the first cycle, all of which were resolved on the day of the occurrence or the following day. The second cycle was administered in 11 of 14 patients with infusion-related reactions. No recurrence of infusion-related reactions was seen in all 11 patients. It is important to use PLD with close attention to the condition of patients at the first administration of PLD. Infusion-related reaction is related to the initial infusion rate of PLD. It has been reported that decreasing the infusion rate reduces the risk of the infusion-related reaction (21).

It has been reported that cardiac toxicity, which is a significant problem with the use of conventional doxorubicin, associated with PLD is mild (22). Also in this trial, all cardiac toxicities observed were Grade 1, and had no effect on continuation of the trial. Furthermore, no patients experienced Grade 2 or higher alopecia, and Grade 3 or higher gastrointestinal toxicities were rarely seen in our trial. These toxicities are frequently induced by treatment of conventional doxorubicin.

These results suggest that toxicity of PLD is manageable by dose modification of PLD and supportive care.

Most patients with ovarian carcinoma exhibited response to first-line chemotherapy, however, the incidence of recurrence is high and prognosis is poor. It might be important to recognize that the chemotherapy would be palliative treatment for treatment of recurrent ovarian carcinoma. PLD has a safety profile that is different from that of platinum and taxanes, which are used for the standard first-line chemotherapy. PLD has a low risk of enhancing cumulative toxicities (haematological toxicity or neurotoxicity) associated with first-line chemotherapy. PLD is expected to have a beneficial effect against disease progression as the proportion of patients with CR, PR or SD and time to progression were 60.3% and 166 days (median). Furthermore, PLD might make it easy to provide long-term outpatient chemotherapy since PLD would reduce a patient burden by dosing once every 4 weeks.

In conclusion, this trial demonstrated that PLD (50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks) was expected to have antitumour effect in Japanese patients with Müllerian carcinoma previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and that toxicities associated with PLD are manageable by dose modification and supportive care. In the USA and Europe, combination chemotherapy with PLD and platinum has recently been investigated in the platinum-sensitive group where PLD is considered to be more effective (23,24,25). It is desirable to investigate the optimal regimen of the combination therapy in Japan.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend special thanks to Dr N. Saijo (National Cancer Center Hospital East, Chiba), Dr S. Isonishi (Jikei University School of Medicine, Tokyo), Dr H. Katabuchi (Kumamoto University, Kumamoto), Dr T. Koyama (Kyoto University, Kyoto), Dr K. Miyagawa (National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo), Dr H. Watanabe (National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo), Dr K Hasegawa (Inamino Hospital, Hyogo), Dr Y. Matsumura (National Cancer Center Research Institute East, Chiba), Dr T. Tamura (National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo) and Dr Y. Ohashi (University of Tokyo, Tokyo) for careful review of the protocol and the clinical data in this study.

References

- 1.Udagawa Y, Yaegashi Y. Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology. 2nd edn. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd; 2007. Ovarian Cancer Treatment Guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markman M, Zaino RJ, Fleming PA, Gemignani ML. Carcinoma of the Fallopian Tube. In: Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC, Barakat R, Markman M, Randall M, editors. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. 4th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 1035–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlan BY, Markman MA, Eifel PJ. Ovarian Cancer, Peritoneal Carcinoma, and Fallopian Tube Carcinoma. In: Devita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles & Practice of Oncology. 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1364–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. Liposomes containing synthetic lipid derivatives of poly (ethylene glycol) show prolonged circulation half-lives in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1066:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain RK. Vascular and interstitial barriers to delivery of therapeutic agents in tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990;9:253–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00046364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodle MC. Surface-modified liposomes: assessment and characterization for increased stability and prolonged blood circulation. Chem Phys Lipids. 1993;64:249–62. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(93)90069-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needham D, McIntosh TJ, Lasic DD. Repulsive interactions and mechanical stability of polymer-grafted lipid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1108:40–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SK, Martin FJ, Jay G, Vogel J, Papahadjopoulos D, Friend DS. Extravasation and transcytosis of liposomes in Kaposi's sarcoma-like dermal lesions of transgenic mice bearing the HIV tat gene. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:10–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang SK, Lee KD, Hong K, Friend DS, Papahadjopoulos D. Microscopic localization of sterically stabilized liposomes in colon carcinoma-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5135–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muggia FM, Hainsworth JD, Jeffers S, Miller P, Groshen S, Tan M, et al. Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin in refractory ovarian cancer: antitumor activity and toxicity modification by liposomal encapsulation. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:987–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon AN, Granai CO, Rose PG, Hainsworth J, Lopez A, Weissman C, et al. Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin in platinum- and paclitaxel-refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3093–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston SRD, Gore ME. Caelyx: phase II studies ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(Suppl. 9):S8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, Parkin DE, Gore ME, Lacave AJ. Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3312–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon AN, Tonda M, Sun S, Rackoff W. Long-term survival advantage for women treated with pegylated loposomal doxorubicin compared with topotecan in a phase 3 randomized study of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Byrne KJ, Bliss P, Graham JD, Gerber J, Vasey PA, Khanna S, et al. A phase III study of Doxil/Caelyx versus paclitaxel in platinum-treated, taxane-naive relapsed ovarian cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:203a. [Abstract 808] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™. Ovarian Cancer V.1.2008. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/ovarian.pdf .

- 17.National Cancer Institute. Ovarian Epithelial Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) Health Professional Version Recurrent or Persistent Ovarian Epithelial Cancer. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/ovarianepithelial/HealthProfessional/page7 .

- 18.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Ovarian cancer (advanced) - paclitaxel, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride and topotecan for second-line or subsequent treatment of advanced ovarian cancer. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA91 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujisaka Y, Horiike A, Shimizu T, Yamamoto N, Yamada Y'Tamura T. Phase 1 Clinical Study of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin (JNS002) in Japanese Patients with Solid Tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:768–74. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mutch DG, Orlando M, Goss T, Teneriello MG, Gordon AN, McMeekin SD, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Gemcitabine Compared With Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin in Patients With Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2811–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanan-Khan A, Szebeni J, Savay S, Liebes L, Rafique NM, Alving CR, et al. Complement activation following first exposure to pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil®): possible role in hypersensitivity reactions. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1430–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien MER, Wigler N, Inbar M, Rosso R, Grischke E, Santoro A, et al. Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYXTM/Doxil®) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:440–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrero JM, Weber B, Geay JF, Lepille D, Orfeuvre H, Combe M, et al. Second-line chemotherapy with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin is highly effective in patients with advanced ovarian cancer in late relapse: a GINECO phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:263–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.du Bois A, Pfisterer J, Burchardi N, Loibl S, Huober J, Wimberger P, et al. Combination therapy with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin in gynecologic malignancies: A prospective phase II study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and Kommission Uterus (AGO-K-Ut) Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:518–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberts DS, Liu PY, Wilczynski SP, Clouser MC, Lopez AM, Michelin DP, et al. Randomized trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) plus carboplatin versus carboplatin in platinum-sensitive (PS) patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian or peritoneal carcinoma after failure of initial platinum-based chemotherapy (Southwest Oncology Group Protocol S0200) Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108:90–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]