Abstract

Twelve xanthone constituents of the botanical dietary supplement, mangosteen (the pericarp of Garcinia mangostina) were screened using a non-cellular, enzyme-based microsomal aromatase inhibition assay. Of these compounds, garcinone D (3), garcinone E (5)α-mangostin (8), and γ-mangostin (9) exhibited dose-dependent inhibitory activity. In a follow-up cell-based assay using SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells that express high levels of aromatase, the most potent of these four xanthones was γ-mangostin (9). Because xanthones may be consumed in substantial amounts from commercially available mangosteen products, the consequences of frequent intake of mangosteen botanical dietary supplements requires further investigation to determine their possible role in breast cancer chemoprevention.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer afflicting females worldwide, with over one million incident cases in the year 2000, and close to 400,000 deaths. 1 In the United States, it was estimated that in 2007 over 178,000 women would be newly diagnosed with breast cancer with over 40,000 deaths occurring from the disease. 2 Estrogens and the estrogen receptors (ERs) are widely recognized to play an important role in the development and progression of hormone-dependent breast cancer, making estrogens and ERs widely studied molecular targets.3, 4 Estrogens have various effects throughout the body including positive effects on the brain, bone, heart, liver, and vagina, with negative effects such as increased risk of breast and uterine cancers with prolonged estrogen exposure.5,6

One method to decrease estrogen production involves aromatase inhibition, with clinically available agents exhibiting almost complete estrogen ablation in postmenopausal women. Aromatase (estrogen synthase) is responsible for catalyzing the biosynthesis of estrogens from androgens and is a cytotochrome P450 enzyme complex that is encoded by the aromatase gene CYP19 for which the expression is regulated by tissue-specific promoters, implying that aromatase expression is regulated differently in various tissues. 4,7,8 Inhibition of the aromatase enzyme has been shown to reduce estrogen production throughout the body to nearly undetectable levels and is proving to have significant affect on the development and progression of hormone-responsive breast cancers. As such, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) can be utilized as either cancer chemotherapeutic agents or for cancer chemoprevention.9,10

Although synthetic AIs show a better side effect profile when compared to tamoxifen, serious side effects still occur, generally related to estrogen deprivation. Synthetic AIs such as anastrozole (Arimidex®), letrozole (Femara®), and exemestane (Aromasin®) may cause decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis,11 increases in cardiovascular events and alterations in patient lipid profiles,12 and can also affect cognition, decreasing the protective effects of estrogens on memory loss with aging.13 Some of the side effects of synthetic AIs can be partially alleviated using available therapies, including osteoporosis and cholesterol medicines.11,14

With the clinical success of several synthetic AIs for the treatment of postmenopausal breast cancer, researchers have been investigating the potential of natural products as AIs.15–17 Plants that have been used traditionally for nutritional or medicinal purposes (for example, botanical dietary supplements and ethnobotanically utilized species) may provide constituents having AI activity but with reduced side effects, possibly resulting from other compounds within the matrix that alleviate some of the side effects of estrogen deprivation (e.g., phytoestrogens).18,19 As such, natural product AIs may be important for the translation of AIs from their current clinical uses as chemotherapy agents to future clinical uses in breast cancer chemoprevention. New natural product AIs may be clinically useful for treating postmenopausal breast cancer and may also act as chemopreventive agents for preventing secondary recurrence of breast cancer. Phase I clinical trials have recently begun on the botanical dietary supplement IH636 grape seed extract for the prevention of breast cancer in postmenopausal women who are at increased risk of developing breast cancer.17,20

As part of a screening program to identify natural product AIs, the methanol- and chloroform-soluble extracts of the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana L. (Clusiaceae) (mangosteen) were tested for their ability to inhibit aromatase in a non-cellular, radiometric microsomal aromatase assay. Also tested for their ability to inhibit aromatase in this microsomal assay were 12 xanthones previously isolated from G. mangostana.17 Following evidence of activity in this preliminary assay, these two extracts and four of the xanthones were evaluated in a follow-up cell-based aromatase inhibition assay. The results obtained will be discussed herein.

Results and Discussion

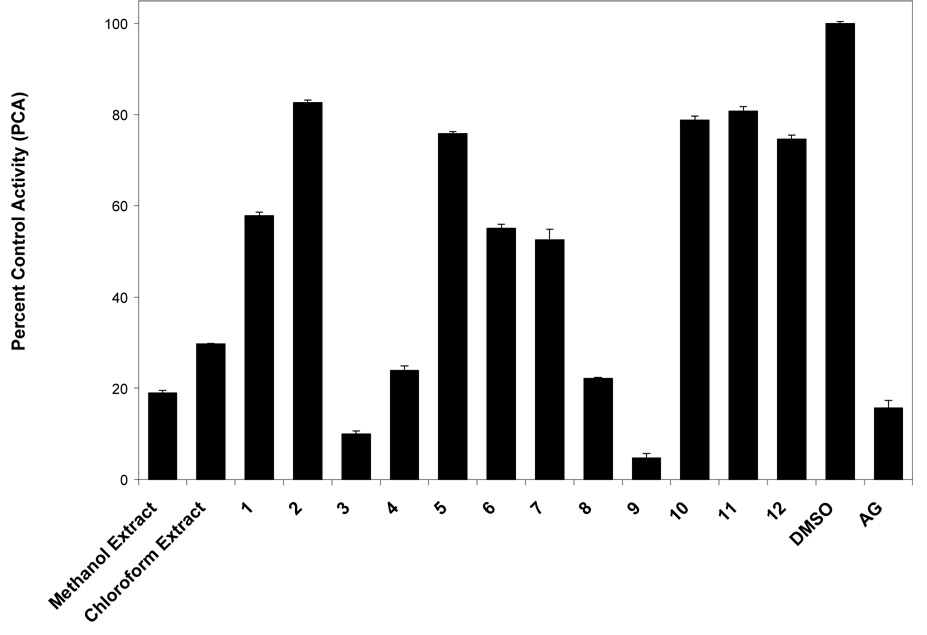

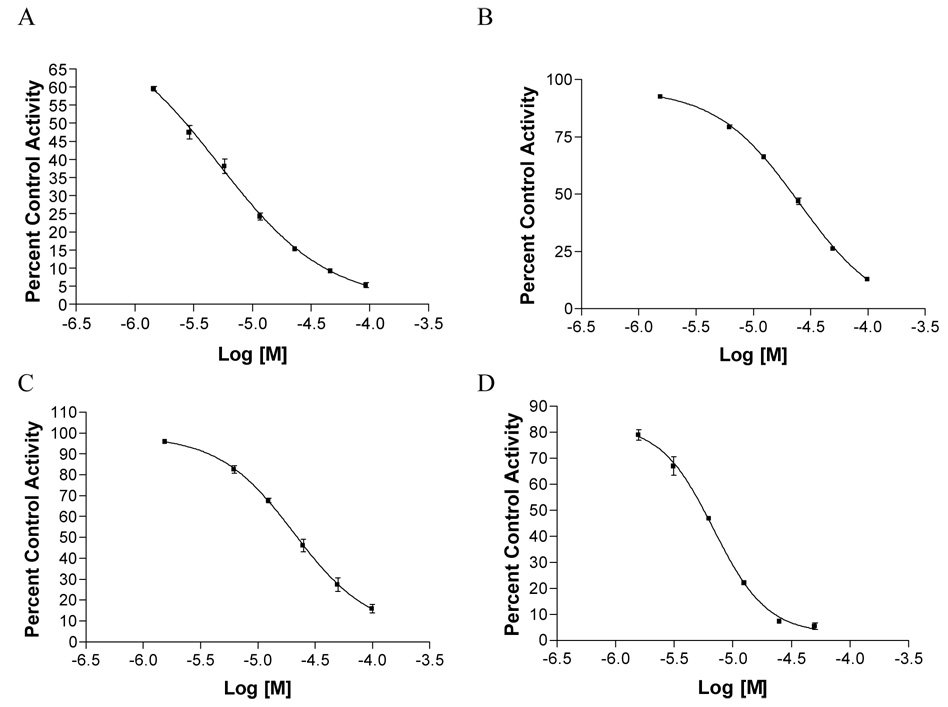

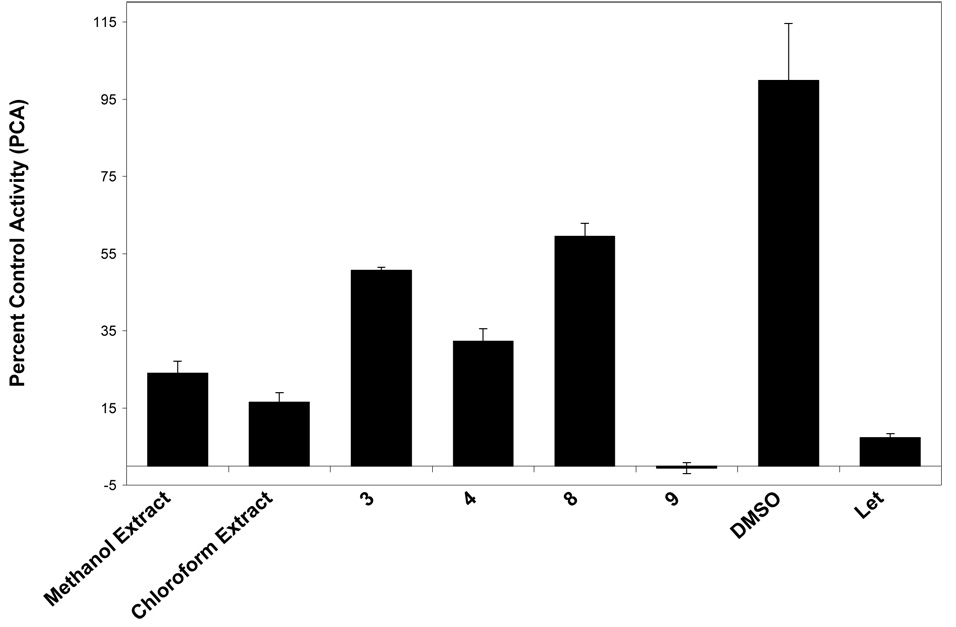

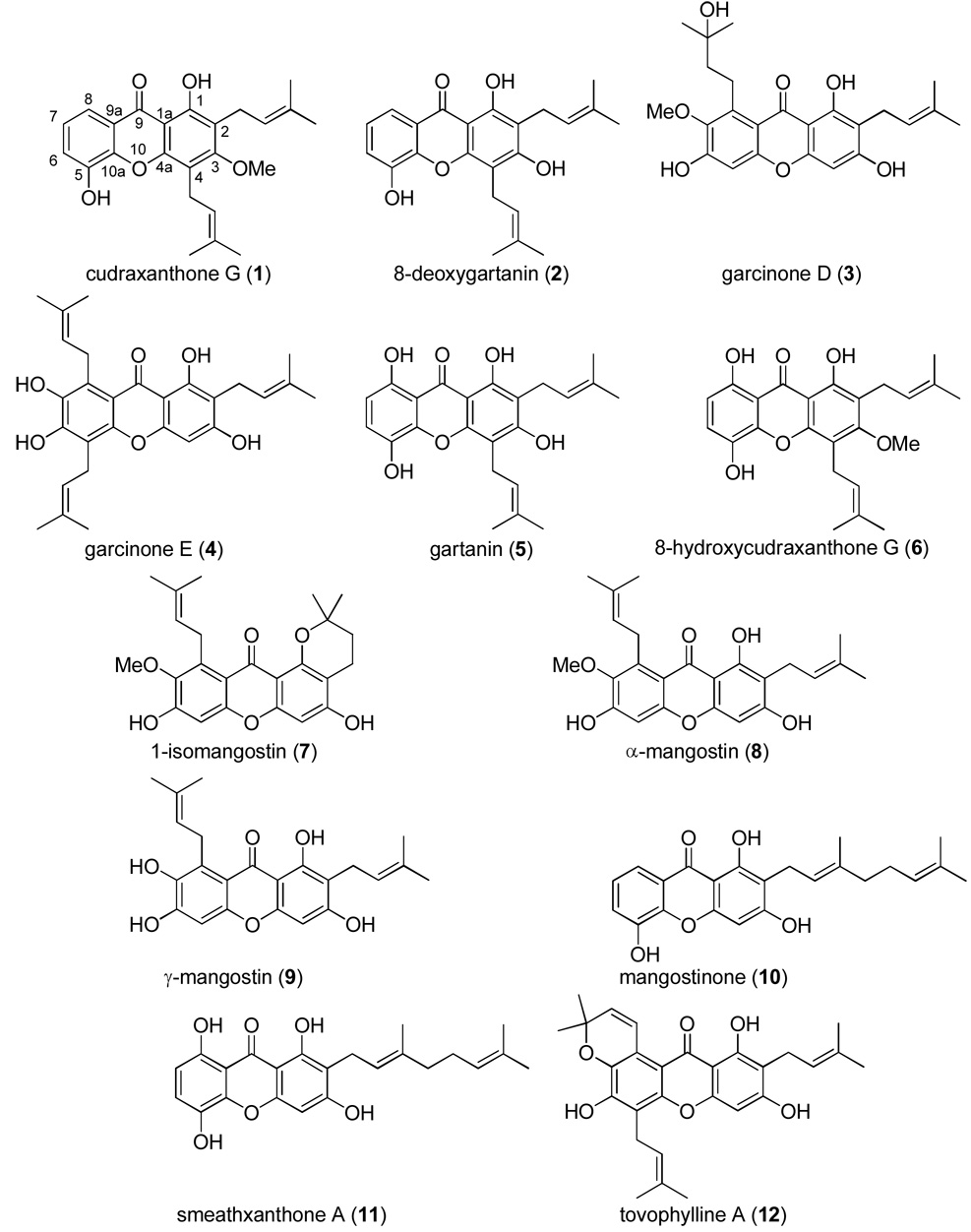

During the present study, the methanol and chloroform-soluble extracts of G. mangostana were both found to be strongly inhibitory against aromatase in the microsomal assay (Table 1, Figure 1). A small library of 12 pure xanthones (1–12), isolated from G. mangostana,21 were tested for aromatase inhibition in microsomes. Compounds were arbitrarily designated as strongly active if their percent control activity (PCA) was 0 – 10, moderately active if their PCA was >10 – 30, weakly active if their PCA was 30 – 50, and inactive if their PCA was greater than 50. Active compounds were then subjected to IC50 testing to determine if they acted in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2). Two xanthones, γ-mangostin (9, 4.7 PCA, IC50 6.9 µM) and garcinone D (3, 10.0 PCA, IC50 5.2 µM), were found to be strongly active in microsomes (Table 1, Figure 1) Figure 2. Two other xanthones, α-mangostin (8, 22.2 PCA, IC50 20.7 µM) and garcinone E (4, 23.9 PCA, IC50 25.1 µM), were found to be moderately active in this microsomal assay. All other xanthones tested (1, 2, 5–7, and 10–12) were inactive.

Table 1.

Percent Control Activity (PCA) Values for Non-cellular, Enzyme-based and SK-BR-3 Cell-based Aromatase Bioassays and IC50 Values for the Non-cellular, Enzyme-based Bioassay for Xanthones 1–12.

| non-cellular bioassay | cell-based bioassay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | IC50 | PCA | cytotoxicity | |||||

| sample | (20 µg/mL) | SEM | (µM) | SEM | (% survival) | SEM | ||

| MeOH extracta | 18.9 | 0.76 | 24.1a | 3.06 | 65.7 | 1.23 | ||

| CHCl3 extracta | 29.8 | 1.97 | 16.5a | 2.39 | 58.5 | 1.18 | ||

| 1 | 57.8 | 0.47 | ||||||

| 2 | 82.6 | 0.61 | ||||||

| 3 | 10.0 | 0.87 | 5.2 | 50.7b | 0.78 | 89.4 | 1.32 | |

| 4 | 23.9 | 0.50 | 25.1 | 32.3b | 3.23 | 52.3 | 0.73 | |

| 5 | 75.9 | 2.84 | ||||||

| 6 | 55.1 | 0.87 | ||||||

| 7 | 52.6 | 1.06 | ||||||

| 8 | 22.2 | 0.93 | 20.7 | 59.4b | 3.49 | 18.4 | 0.70 | |

| 9 | 4.7 | 1.20 | 6.9 | −0.5b | 1.45 | 30.5 | 0.54 | |

| 10 | 78.8 | 1.07 | ||||||

| 11 | 80.8 | 1.01 | ||||||

| 12 | 74.7 | 1.62 | ||||||

| DMSOc | 100.0 | 0.44 | 100.0 | 14.71 | 100.0 | 1.19 | ||

| AGc | 15.7c | 0.55 | ||||||

| Letd | 7.4d | 1.05 | ||||||

Methanol and chloroform extracts of mangosteen (G. mangostana). Extracts were tested at 20 µg/mL in both non-cellular and cell-based assays.

Compounds 3, 4, 8, and 9 were tested at 50 µM in the cell-based assay.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), blank/negative control for both noncellular and cell-based bioassay.

Aminoglutethimide (AG, 50 µM), positive control for non-cellular bioassay.

Letrozole (Let, 10 nM), positive control for cell-based bioassay.

Figure 1.

Percent control activity (PCA) of extracts (at 20 µg/mL) and compounds (at 20 µg/mL) from mangosteen (G. mangostana) tested in a noncellular, enzyme-based, microsomal aromatase bioassay (DMSO = dimethylsulfoxide, blank/negative control; AG = aminoglutethimide, positive control, 50 µM).

Figure 2.

IC50 curves for active compounds from mangosteen: (A) garcinone D (3, IC50 = 5.16 µM), (B) garcinone E (4, IC50 = 25.14 µM), (C) α-mangostin (8, IC50 = 20.66 µM), and (D) γ-mangostin (9, IC50 = 6.88 µM).

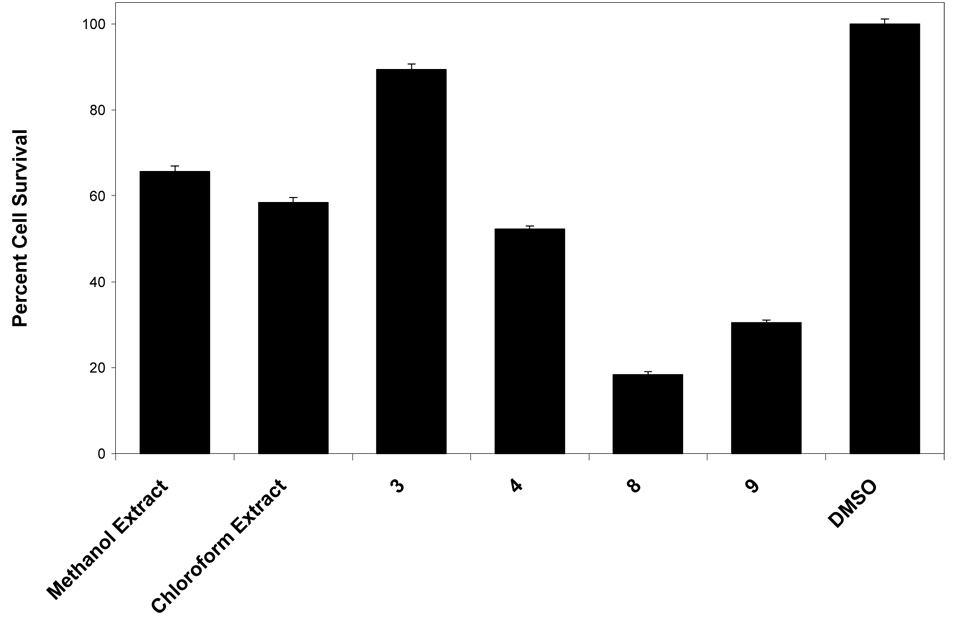

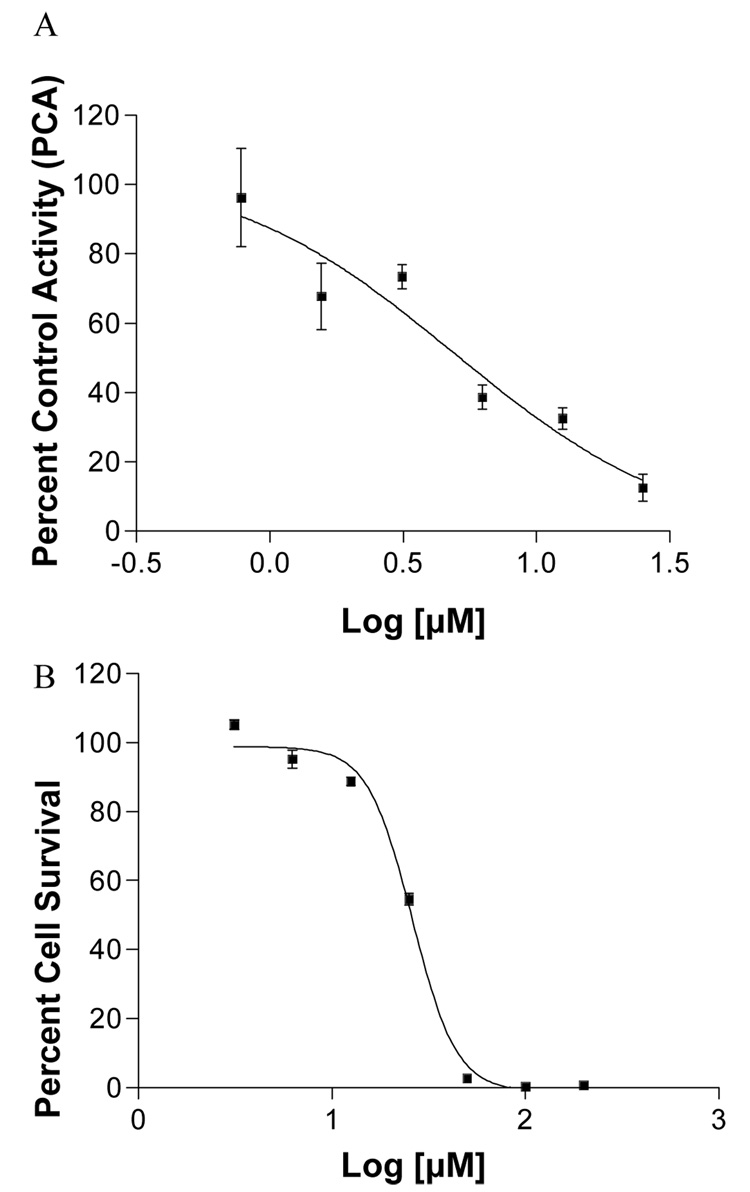

To determine if the G. mangostana MeOH and CHCl3 extracts and compounds 3, 4, 8, and 9 inhibited aromatase in a more biologically relevant, cell-based assay, these samples were then tested at 50 µM in a secondary cell-based assay, using SK-BR-3 human breast cancer cells that overexpress the aromatase enzyme. Inhibitory activity was evident for both of the two mangosteen extracts, with γ-mangostin (9) being the only one of the four compounds found to strongly inhibit aromatase in cells (−0.5 PCA), garcinone E (4) being moderately inhibitory (32.3 PCA), and garcinone D (3) and α-mangostin less so (> 50 PCA) (Table 1). However, γ-mangostin (9) was also found to be fairly cytotoxic in SK-BR-3 cells (Figure 4), complicating the determination if the aromatase inhibition was due to actual activity or the result of low cell survival. Therefore, γ-mangostin (9) was further subjected to IC50 testing in both the SK-BR-3 cell-based aromatase assay and SK-BR-3 cell-based cytotoxicity assay (Figure 5). The IC50 of γ-mangostin (9) in the cell-based AI assay was determined to be 4.97 ± 1.9 µM, while the IC50 in the cell-based cytotoxicity assay was found to be 25.99 ± 1.0 µM. Using the concept of a chemopreventive index (CI), which provides an indication of the therapeutic index and can be computed using the equation CI = cytotoxicity IC50/aromatase inhibition IC50,22 the CI for γ-mangostin (9) was calculated as 5.2, thus indicating over five times stronger inhibition of aromatase than cytotoxicity. As such, γ-mangostin (9) and the botanical dietary supplement mangosteen show considerable activity as aromatase inhibitors. Further molecular and in vivo studies should be performed to advance their development in this regard.

Figure 4.

Percent cell survival of extracts and compounds from mangosteen (G. mangostana) tested in a SK-BR-3 cell-based cytotoxicity bioassay (DMSO = dimethylsulfoxide, blank/negative control).

Figure 5.

IC50 curves for γ-mangostin (9) in (A) SK-BR-3 aromatase bioassay (IC50 = 4.97 µM), and (B) SK-BR-3 cytotoxicity bioassay (IC50 = 25.99 µM).

Xanthones 3, 4, 8, and 9 are among the most potent natural products known to date in the microsomal AI assay. Apart from being based on a xanthone nucleus, these four compounds have several structural features in common. Of the 12 xanthones tested, 3, 4, 8, and 9 are the only substances to bear hydroxy groups at C-1, C-3, and C-6, a prenyl group at C-2, and a 5 carbon substituent at C-8. Furthermore, in the cell-based AI assay, hydroxylation at C-7 (compounds 9 and 4) was shown to elicit more aromatase inhibition than C-7 methoxylation (compounds 3 and 8) (Table 1), with methoxylation leading to higher cytotoxicity than hydroxylation. Xanthones have only recently been tested for their ability to inhibit aromatase, with several synthetic xanthones exhibiting activity in the nanomolar range,23,24 but xanthones have not yet undergone extensive evaluation using additional in vitro, in vivo, or preclinical models. Further comparisons of the structure-activity relationship with both natural and synthetic xanthones should help to identify potential lead candidates for future development.

Xanthones are well known for their numerous and varied pharmacological effects, including having antioxidant, antimicrobial, central nervous system (CNS) depressant or stimulant, antihypertensive, antidiabetic, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and/or immunomodulation properties.23 Xanthones used during the present study were isolated from Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen), a slow-growing tropical tree with edible fruits.21 Mangosteen is commonly refered to as the “queen of fruits,” prized for its delicious fruits and has been utilized in Southeast Asian traditional medicine for stomach ailments (pain, diarrhea, dysentery, ulcers), as well as to treat infections and wounds.25,26

Owing to their activity as potent antioxidants,21,27–29 some mangosteen-based botanical products are standardized to contain high levels of xanthones such as α- and γ-mangostin. Mangosteen products have recently become one of the top-selling botanical dietary supplements in the U.S., and in 2005 represented the sixth-ranked single-herb dietary supplement with sales of over 120 million dollars, a substantial increase over the previous year.30 The results from the present study, including the testing of both mangosteen extracts and compounds, indicate that certain xanthones from mangosteen fruits act as potent aromatase inhibitors in both noncellular and cell-based AI assays, especially γ-mangostin (9). Approximately two-thirds of post-menopausal women with breast cancer have the estrogen-dependent (hormone-dependent) form of this disease, in which estrogen is required for the growth of tumors.31 Because of their relatively high yield of xanthones such as α- and γ-mangostin (8 and 9) in the pericarp of G.mangostana,e.g.,21 mangosteen botanical dietary supplements may be acting as aromatase inhibitors, and might thus have a potential role in cancer chemoprevention for postmenopausal women with hormone-dependent breast cancer. However, before a definitive role of the mangosteen xanthones in this regard can be ascertained, additional work will need to be performed, including evaluation of the in vitro aromatase inhibitory xanthone constituents in an appropriate in vivo model.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

Methanol and chloroform-soluble extracts of Garcinia mangostana L. (Clusiaceae) (mangosteen) were prepared and individual xanthones were isolated as described in a previous publication.21 Radiolabeled [1β-3H]androst-4-ene-3,17-dione, scintillation cocktail 3a70B, SK-BR-3 human breast cancer cells were obtained as described previously.31 Radioactivity was counted on an LS6800 liquid scintillation counter (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Noncellular, Enzyme-based Aromatase Bioassay

This was carried out as described in earlier publications.32–34 Human placental microsomes were obtained from human term placentas that were processed at 4 °C immediately after delivery from the OSU Medical Center [OSU Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol number 2002H0105, last approved in December 2006]. Extracts and compounds were originally screened at 20 µg/mL in DMSO using a noncellular microsomal radiometric aromatase assay. Samples [extracts or compounds, DMSO as negative control, or 50 µM (±)-aminoglutethimide (AG) as positive control] were tested in triplicate. Each reaction mixture included sample, 100 nM [1β-3H]androst-4-ene-3,17-dione (400,000 – 450,000 dpm), 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 5% propylene glycol, and an NADPH regenerating system (containing 2.85 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 1.8 mM NADP+, and 1.5 units glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase). Microsomal aromatase (50 µg) was added to initiate the reactions, which were then incubated in a shaking water bath at 37 °C, and quenched after 15 min using 2 mL CHCl3. An aliquot of the aqueous layer was then added to 3a70B scintillation cocktail for quantitation of the formation of 3H2O. Percent control activity (PCA) and IC50 values were determined as previously indicated.32–34

Cell-based Aromatase Bioassay

Extracts and compounds found to be active using the noncellular, enzyme-based radiometric aromatase inhibition assay were further tested at various concentrations in SK-BR-3 human breast cancer cells that overexpress aromatase, using previously described methodology.34–36 Cells were treated with samples or 0.1% DMSO (negative control) or 10 nM letrozole (positive control) [in triplicate]. Results are initially determined as picomoles of 3H2O formed per hour incubation per million live cells (pmol/h/106 cells), with PCA calculated by comparison with negative control, DMSO.

Cell Viability Analysis

The effect of extracts and compounds on SK-BR-3 cell viability was assessed using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium (MTT) bromide assay in six replicates, as previously described.37 Results are expressed as percent cell survival as compared to the negative control, DMSO.

Figure 3.

Percent control activity (PCA) of extracts (at 20 µg/mL) and compounds (at 50 µM) from mangosteen (G. mangostana) tested in a SK-BR-3 cell-based aromatase bioassay (DMSO = dimethylsulfoxide, blank/negative control; Let = letrozole, positive control, 10 nM)).

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for financial support through a University Fellowship and a Dean’s Scholar Award from the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Chicago, awarded to M.J.B. Other support was provided by NIH grant R01 CA73698 (P.I., R.W.B.), The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (OSUCCC) Breast Cancer Research Fund (to R.W.B.) and the OSUCCC Cancer Chemoprevention Program (to A.D.K.).

References and Notes

- 1.Parkin DM. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:533–543. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborne CK, Schiff R, Fuqua SAW, Shou J. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:4338s–4342s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brueggemeier RW, Richards JA, Petrel TA. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;86:501–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuller LH, Matthews KA, Meilahn EN. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;74:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfaff DW, Vasudevan N, Kia HK, Zhu Y-S, Chan J, Garey J, Morgan M, Ogawa S. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000;74:365–373. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamat A, Hinshelwood MM, Murry BA, Mendelson CR. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;13:122–128. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulun SE, Sebastian S, Takayama K, Suzuki T, Sasano H, Shozu M. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;86:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brueggemeier RW. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2006;7:1919–1930. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.14.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendall A, Dowsett M. Endocr. Rel. Cancer. 2006;13:827–837. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gnant M. Cancer Invest. 2006;24:328–330. doi: 10.1080/07357900600633759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Geller M, Col N. Clin. Breast Cancer. Vol. 6. 2006. pp. S58–S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yue X, Lu M, Lancaster T, Cao P, Honda S, Staufenbiel M, Harada N, Zhong Z, Shen Y, Li R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:19198–19203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505203102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esteva FJ, Hortobagyi GN. Breast. 2006;15:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanderson JT, Hordijk J, Denison MS, Springsteel MF, Nantz MH, van den Berg M. Toxicol. Sci. 2004;82:70–79. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grube BJ, Eng ET, Kao YC, Kwon A, Chen S. J. Nutr. 2001;131:3288–3293. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.12.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eng ET, Ye J, Williams D, Phung S, Moore RE, Young MK, Gruntmanis U, Braunstein G, Chen S. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8516–8522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edmunds KM, Holloway AC, Crankshaw DJ, Agarwal SK, Foster WG. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 2005;45:709–720. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2005055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basly JP, Lavier MC. Planta Med. 2005;71:287–294. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kijima I, Phung S, Hur G, Kwok SL, Chen S. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5960–5967. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung H-A, Su B-N, Keller WJ, Mehta RG, Kinghorn AD. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:2077–2082. doi: 10.1021/jf052649z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pezzuto JM, Kosmeder II JW, Park E-J, Lee SK, Cuendet M, Gills J, Bhat K, Grubjesic S, Park H-S, Mata-Greenwood E, Tan Y, Yu R, Lantvit DD, Kinghorn AD. Characterization of natural product chemopreventive agents. In: Kelloff GJ, Hawk ET, Sigman CC, editors. Cancer Chemoprevention, Volume 2: Strategies for Cancer Chemoprevention. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinto MM, Sousa ME, Nascimento MS. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005;12:2517–2538. doi: 10.2174/092986705774370691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Recanatini M, Bisi A, Cavalli A, Belluti F, Gobbi S, Rampa A, Valenti P, Palzer M, Palusczak A, Hartmann RW. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:672–680. doi: 10.1021/jm000955s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto K, Akao Y, Kobayashi E, Ohguchi K, Ito T, Tanaka T, Iinuma M, Nozawa Y. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:1124–1127. doi: 10.1021/np020546u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moongkarndi P, Kosem N, Kaslungka S, Luanratana O, Pongpan N, Neungton N. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshikawa M, Harada E, Miki A, Tsukamoto K, Liang SQ, Yamahara J, Murakami N. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1994;114:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu LM, Zhao MM, Yang B, Zhao QZ, Jiang YM. Food Chem. 2007;104:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin Y-W, Jung H-A, Chai H, Keller WJ, Kinghorn AD. Phytochemistry. 2007. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anonymous. Nutrition Business Journal. San Diego, CA: Penton Media, Inc; 2005. NBJ's Supplement Buisiness Report 2006, an Analysis of Markets, Trends, Competition and Strategy in the U.S. Dietary Supplement Industry; pp. 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brueggemeier RW, Diaz-Cruz ES, Li PK, Sugimoto Y, Lin YC, Shapiro CL. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;95:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellis JT, Jr, Vickery LE. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:4413–4420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Reilly JM, Li N, Duax WL, Brueggemeier RW. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:2842–2850. doi: 10.1021/jm00015a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balunas MJ, Su B, Landini S, Brueggemeier RW, Kinghorn AD. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:700–703. doi: 10.1021/np050513p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natarajan N, Shambaugh GE, 3rd, Elseth KM, Haines GK, Radosevich JA. Biotechniques. 1994;17:166–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards JA, Brueggemeier RW. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:2810–2816. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su B, Landini S, Davis DD, Brueggemeier RW. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:1635–1644. doi: 10.1021/jm061133j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]