Abstract

The simple and efficient asymmetric synthesis of 3°-carbamines 7 from N-TMS enamines (3) and either enantiomeric form of B-allyl-10-(phenyl)-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decane (1) is reported. The high reactivity (<1 h, −78 °C) and enantioselectivity (60– 98% ee) of these substrates can be attributed to the fact that the complexation of 3 with 1 facilitates its isomerization to the corresponding syn-N-TMS ketimine complex from which allylation can occur. In addition to providing the homoallylic amines 7 with predictable stereochemistry, the procedure also permits the efficient recovery of the chiral boron moiety (50–65%) as air-stable crystalline pseudoephedrine complexes 8 which are directly converted back to 1 with allylmagnesium bromide in ether (98%).

The synthesis of non-racemic 3°-carbamines from the asymmetric allylation of achiral ketimines represents an important synthetic challenge. These amines can be prepared through the asymmetric addition of Grignard and organolithium reagents to unsymmetrical chiral N-sulfinyl ketimines.1 The asymmetric allylsilylation of ketone-derived N-benzoylhydrazones was also demonstrated to provide these non-racemic 3°-carbamines after the SmI2-mediated reduction of the resulting homopropargylic hydrazines.2 While no analogous asymmetric allylboration process is known for achiral ketimines or related compounds, new allylboranes and processes have been recently reported for the asymmetric allylboration of ketones.3 Among these, the B-allyl-10-phenyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.2]decanes (9-BBDs) (1) contain a nearly ideal chiral pocket for the highly enantioselective allylation of methyl ketones.3a In the present study, we wish to report the asymmetric allylboration of N-TMS ketimines 2 generated in situ from the reaction of N-TMS enamines 3 with 1. The new process can be viewed as occurring through an initial complex 4 followed by isomerization to 5, allylation giving 6 which provides the desired 3°-carbamines 7 after a pseudoephedrine (PE) workup (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

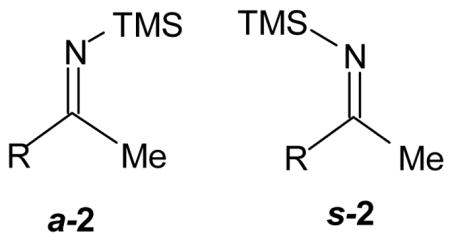

Clearly, 3 is not an obvious choice as a substrate for the allylboration process. In fact, our plan was to follow an earlier protocol which was successful for the allylboration of N-H aldimines derived from the borane-mediated methanolysis of their N-TMS precursors.4 Since the allylboration of the aldimines with the BBD systems does not occur until the N-TMS derivatives are converted to their N-H counterparts,4e we anticipated that similar behavior, namely that 1 would smoothly allylate the N-H ketimines derived from 2 in a predictable manner (c.f., 9, 10).5 Mixtures of the anti-N-TMS ketimines (a-2) and 3 were prepared through the Rochow protocol6 from nitriles and LiMe followed by TMSCl (75–95%). These mixtures are thermally unstable and heating usually increases the amount of 3 and also gives rise to minor amounts of the syn-ketimine s-2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

N-TMS ketimines and enamines from nitriles

| R | series | a-2:3a | s-2:a-2:3b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ph | a | 94:6 | 16:22:62 |

| 2-MeOC6H4 | b | 70:30 | 4:4:92 |

| 4-MeOC6H4 | c | 40:60 | 5:48:47 |

| t-Bu | d | 80:20 | - |

| c-Hx | e | 60:40 | - |

| 4-BrC6H4 | f | 45:55 | 15:35:50 |

| 4-MeC6H4 | g | 74:26 | 5:36:59 |

| 3-Py | h | 60:40 | 4:9:87 |

| 4-Me2NC6H4 | i | 81:19 | - |

| 4-ClC6H4 | j | 60:40 | 10:26:64 |

| 2-thienyl | k | 87:13 | 0:70:30 |

The a-2:3 ratios were estimated from the 13C NMR analysis of the peak areas for the TMS signals. Other characteristic signals for these tautomers were also observed in each case.

The a-2:3 mixtures were heated at reflux temperature (24–72 h) and the ratios of s-2, a-2 and 3 were estimated as above (see SI).

Treatment of a-2a:3a (90:10) with a 1:1 mixture of 1 and MeOH at −78 °C results in the clean formation of the desired N-boryl homoallylic amine (11B NMR δ 51). An oxidative work-up provided 7aR in 80% yield and 52% ee. The R configuration of 7aR is consistent with the allylboration of PhCOMe with 1 (i.e., R, 96% ee).3a The lesser ee for a-2a:3a vs PhCOMe parallels a similar pattern observed in the allylboration of N-H aldimines vs aldehydes with B-allyl-10-TMS-9-BBD.4e Our models for the key pre-transition states for these two processes are illustrated above (c.f., 9 and 10).

Seeking a more selective reaction protocol, we prepared (±)-BEt-10-Ph-9-BBD (11) as a non-reacting model for 1. Its complexation with PhMeC=NH (4 equiv) was examined by 11B NMR revealing that 11 (δ83) was completely converted to its imine complex (δ 1). Unexpectedly, we also noted that 11 is partially complexed (11B NMR δ −1, ~5%) with the excess 90:10 a-2a:3a mixture at −78 °C even before the addition of MeOH. Moreover, using 4 equiv of the 16:22:62 s-2:a-2:3 mixture increases the complexation with 11 to ~90%.

This suggested that a-2:3 mixtures may undergo allylboration with 1 even without converting the N-TMS to the corresponding N-H ketimine. The allylboration process was examined with (−)-1R at −78 °C employing a 94:6 a-2a:3a mixture (2 equiv) with the finding that the addition was complete in 16 h. Significantly, the homoallylic amine 7a was formed in 92% ee and with the opposite S absolute configuration from that obtained from PhMeC=NH! Moreover, under these same conditions, the 16:22:62 s-2:a-2:3 mixture (2 equiv) also gave 7aS, again in 92% ee, with the reaction being complete in <1 h. This reactivity is consistent with the general process illustrated in Scheme 1 wherein 3 initially forming a complex with 1 which rapidly isomerizes to the reacting 5 complex which leads to 6 and ultimately to 7. Clearly, 5 could also form directly from s-2, but even in cases where this isomer is not present, rapid allylboration occurs provided ample 3 is present to react with 1 as illustrated in Scheme 1. Moreover, to gain additional support for our view of the process, the anti aldimine PhHC=NTMS (2 equiv) was found to partially complex 1 (~20% at −78 °C), but not its 10-TMS counterpart. However this aldimine, despite its being less substituted than a-2a, does not undergo allylboration with either 1 or its 10-TMS counterpart even after one week at 25 °C. These aldimines simply do not have access to their syn isomers because the enamine-based process is not an option for them.

We carried out the allylboration of the 2/3 mixtures (≥2 equiv of 2/3) for 1 h at −78 °C with 1 to ultimately produce 8 (48–65%) and the desired 3°-carbamine 7 (50–82%) in high ee (60–98%) (Table 2). The complex 8 is easily recycled back to 1 (98%) with allylmagnesium bromide in ether.

Table 2.

Asymmetric allylboration of N-TMS ketimines with 1

As can be noted from these results, higher ee’s for 7 are generally observed for aryl derivatives with electron-donating groups in the aromatic ring. Sterically biased examples (e.g., 3d) also provide excellent substrates for this process. For the 4-BrC6H4 (f) series, we also prepared the mixture of N-triethylsilyl (TES) ketimine and its enamine (81:19). This also underwent allylboration with (+)-1S (1 h, −78 °C) to give 7fR (60%) in somewhat lower ee (50%) than was observed with 3f (70% ee).

Simple MM calculations8 suggest that 3 strongly prefers (a series, ~5 kcal/mol) to complex (−)-1R trans to the 10-Ph group (i.e., 4). Tautomerism leads either to 5 or its rotomer 12.

We view the larger TES vs TMS group as increasing the relative amount of the minor 7fS enantiomer through this “upside-down” isomer which avoids TMS-Ph repulsions. Moreover, through the addition of EtMgBr to PhCN followed by TMSCl, we prepared the N-TMS propiophenone enamines 3l as an 83:17 Z/E mixture free of either ketimine tautomer. This mixture reacts rapidly with (+)-1S (1 h, −78 °C) to give 7lR (67%) in 65% ee.9 Thus, with the larger Et vs Me inward group, repulsions between the BBD ring and this group apparently also increase the amount of 7 originating from this “upside-down” pathway thereby lowering the product ee.

Clearly the carbamines 7 are rare with only 7a being known in non-racemic form.1a,2 With their ready availability through the present methodology, we chose to further demonstrate their utility through their conversion to the corresponding β3,3-amino acids and β-amino aldehydes.1a Thus, acetylation of 7b gives 13b (80%) whose ozonolysis (CH2Cl2, −78 °C) affords 14b (90%) and 15b (57%) with oxidative (H2O2) and reductive (Me2S) work-ups, respectively.

The asymmetric allylboration of ketimines with the BBD reagent 1 has been accomplished in a unique manner utilizing their N-TMS enamines 3 to access the requisite syn-ketimine-allylborane complexes 5. The reagents 1 are readily prepared in either enantiomeric form and are easily recycled providing the 3°-carbamines 7 in high ee (60–98%). With the N-TMS substitution being readily hydrolyzed during work-up, this new method has the advantage of producing the free 3°-carbamines 7 for subsequent conversions.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, analytical data and selected spectra for 1–3, 7–8, 13f, 14f, 15g and derivatives and X-ray data for (+)-8R. (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

The support of the NSF (CHE-0517194), NIH (S06GM8102) and the U. S. Dept. Ed. GAANN Program (P200A030197-04) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Ms. Eduvigis Gonzalez and Dr. Peter Baron for the X-ray structure of (+)-8R.

References

- 1.(a) Hua DH, Wu SW, Chem JS, Iguchi S. J Org Chem. 1991;56:4. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cogan DA, Ellman JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:268. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ellman JA, Owens TD, Tang TP. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:984. doi: 10.1021/ar020066u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger R, Duff K, Leighton JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5686. doi: 10.1021/ja0486418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Canales E, Prasad KG, Soderquist JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11572. doi: 10.1021/ja053865r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu TR, Shen L, Chong JM. Org Lett. 2004;6:2701. doi: 10.1021/ol0490882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wada R, Oisaki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8910. doi: 10.1021/ja047200l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chen GM, Ramachandran PV, Brown HC. Angew Chem Int Engl. 1999;38:825. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990315)38:6<825::AID-ANIE825>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramachandran PV, Burghardt TE. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:4387–4395. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ramachandran PV, Burghardt TE, Ram Reddy MV. J Org Chem. 2005;70:2329. doi: 10.1021/jo048144+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ramachandran PV, Burghardt TE, Bland-Berry L. J Org Chem. 2005;70:7911. doi: 10.1021/jo0508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hernandez E, Canales E, Gonzalez E, Soderquist JA. Pure Appl Chem. 2006;7:1389. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen GM, Brown HC. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4217. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan LH, Rochow EG. J Organometal Chem. 1967;9:231. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexakis A, Frutos JC, Mutti S, Mangeney P. J Org Chem. 1994;59:3326–3334. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Performed using the Spartan ’04 MM program.

- 9.With a 100% excess of E/Z-3l, the less sterically encumbered E-31–1 complex is evidently formed and proceeds to product faster than with Z-31. Unreacted 31 is observed as exclusively the Z isomer.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, analytical data and selected spectra for 1–3, 7–8, 13f, 14f, 15g and derivatives and X-ray data for (+)-8R. (PDF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.