Abstract

Objective:

Persons with ALS differ from those with other terminal illnesses in that they commonly retain capacity for decision making close to death. The role patients would opt to have their families play in decision making at the end of life may therefore be unique. This study compared the preferences of patients with ALS for involving family in health care decisions at the end of life with the actual involvement reported by the family after death.

Methods:

A descriptive correlational design with 16 patient–family member dyads was used. Quantitative findings were enriched with in-depth interviews of a subset of five family members following the patient's death.

Results:

Eighty-seven percent of patients had issued an advance directive. Patients who would opt to make health care decisions independently (i.e., according to the patient's preferences alone) were most likely to have their families report that decisions were made in the style that the patient preferred. Those who preferred shared decision making with family or decision making that relied upon the family were more likely to have their families report that decisions were made in a style that was more independent than preferred. When interviewed in depth, some family members described shared decision making although they had reported on the survey that the patient made independent decisions.

Significance of results:

The structure of advance directives may suggest to families that independent decision making is the ideal, causing them to avoid or underreport shared decision making. Fear of family recriminations may also cause family members to avoid or underreport shared decision making. Findings from this study might be used to guide clinicians in their discussions of treatments and health care decision making with persons with ALS and their families.

Keywords: Decision making, End of life, Family, Ethics

INTRODUCTION

Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) differ from those with other terminal illnesses in that they commonly retain their capacity for decision making close to death (Ganzini et al., 2002). The purpose of this study was to compare the preferences of patients with ALS for family involvement in health care decisions with the actual family involvement in decisions made just before death (decision making concordance). In-depth interviews with a subset of family members provided context for the family experience of decision making. Some studies of decision making by patients with ALS have focused on choices regarding life-sustaining treatment such as long-term mechanical ventilation or feeding tube insertion (Moss et al., 1996; Albert et al., 1999). We found no other study of persons with ALS that compared their preferences for family decision involvement with the actual involvement near death. Findings from this study might be used to guide clinicians in their discussions of treatments and health care decision making with persons with ALS and their family members.

METHODS

Sample

Although part of a larger study that included patients with other conditions (Nolan et al., 2005), the present study reports only on patients enrolled within 8 weeks of being diagnosed with ALS who were being treated at a specialized practice at a major U.S. teaching hospital. The patients were interviewed every 3 months until death or 2 years had elapsed.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board. At the time of enrollment, patients identified a family member who might participate in health care decisions with them and gave investigators permission to contact the family member if the patient became too ill to speak for himself or died. At the start of each interview, we screened and excluded patient subjects for altered mental status using The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (Pfeiffer, 1975; Erkinjuntti, Sulkava, Wikstrom, & Autio, 1987) and The Confusion Assessment Method (Inouye et al., 1990). We then asked patients to think of the most important decision that they had recently made or were about to make regarding their health care. Using a modified version of the Control Preferences Scale, originally developed and validated by Degner and Sloan (1992) and described by Nolan et al. (2005), we asked subjects to indicate how they preferred to make this decision with their family. Subjects used the scale, which is made of illustrated cards, to indicate whether they preferred to make this decision independently, through shared decision making, or through decision making that is reliant on the family.

After the death of the patient, we sent a sympathy card to family members who had consented to participate. Two weeks after this, we contacted the family member to set up an appointment for a phone interview. We then interviewed the family member at the agreed upon time using the Family Member Decision Making Survey. This 30-item survey contains multiple-choice and short-answer questions about the most important health care decision made near death, the involvement of the patient, family, and physician in the decision, use of advance directives, and location at death. The item that asked about family involvement at the end of life was based upon the adapted version of the patient–family dimension of the Decision Control Preferences Scale of Degner and Sloan (1992). Asking the family to think of the most important health care decision made near death, we read the scale choices and asked the family to indicate whether the patient had made this decision independently, through shared decision making with family, or through decision making that was reliant on the family.

In the present study we compared data from the patient's final interview (0 to 3 months before death) with data from family interviews after death. Patients reported the role they would opt for the family to play in decision making. After death, family members reported the actual family involvement in health care decisions near death. Next, we selected family members to be interviewed in depth about the decision-making process. Using criterion sampling (Sandelowski, 2000) to obtain varying views of family decision involvement, we purposively selected both those for whom there had been concordance and those for whom there had been discordance in the patient's preferred and actual involvement of family in health care decisions at the end of life. Family members interviewed were not informed regarding the status of their reported decision making as concordant or discordant with that of the patient.

In-depth qualitative interviews began with broad questions about how the patient had died. Then family members were asked about the types of health care decisions made near death, how they were made, and the extent to which they felt confident in participating in different aspects of health care decisions for the patient's care. These questions were developed based on Bandura's Self-Efficacy Theory (Pajares, 2002). This theory holds that an individual's self-efficacy or confidence that he/she can master a behavior (in this case participating in patient decision making at the end of life) is influenced by three main factors: previous performance of the desired behavior, vicarious experience of observing others perform the desired behavior, and positive feedback from others that one can successfully perform the behavior. In this case, family members were asked whether they had had any previous experience in decision making with or for another family member at the time of death, whether they had observed another person making decisions with or for a family member, or whether they had received positive feedback from anyone about their ability to participate in these types of decisions. Finally, family members were asked the extent to which they were satisfied with the decision-making experience. All interviews were audiotaped with the subject's permission. The tapes were then transcribed by a professional transcriptionist. The investigator who interviewed the subjects reviewed the transcripts for accuracy and corrected any transcription errors.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized data regarding patient and family characteristics and the types of health care decisions made. A bar chart was created to demonstrate patient preferences for family involvement and actual family involvement in health care decisions. Cohen's kappa was used to measure the agreement between these two ratings. Qualitative interview data were analyzed using content analysis. The investigator who conducted the interviews and another investigator reviewed the transcripts sequentially, first separately and then together. These investigators identified subject categories within the transcripts and then themes across the transcripts. They stopped the interviews once thematic saturation was achieved. In the third phase of analysis, a framework was developed regarding the relationships of the themes and categories to one another with input from the other investigators.

RESULTS

A summary of the demographic characteristics of the patients and their relationship to the family member is provided in Table 1. Table 2 lists the types of important health care decisions that the patients reported being made at their final interview. The types of health care decisions that the family members reported being made immediately prior to the death of the patient are also provided along with examples of the decision types. No patient subject was excluded for altered mental status.

Table 1.

Family and patient characteristics (N = 16)

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Patient sex | |

| Male | 50% (8) |

| Female | 50% (8) |

| Patient race | |

| White | 94% (15) |

| Black | 6% (1) |

| Family member | |

| relationship to patient | |

| Spouse | 63% (10) |

| Child | 31% (5) |

| Nonfamily | 6% (1) |

| Patient insurance | |

| Private | 75% (12) |

| Uninsured | 13% (2) |

| Medicare | 6% (1) |

| Missing | 6% (1) |

| Artificial nutrition in use |

|

| Yes | 37% (6) |

| No | 63% (10) |

| Living will | |

| Yes | 87% (14) |

| No | 13% (2) |

| Health care | |

| power of attorney | |

| Yes | 81% (13) |

| No | 19% (3) |

| Patient location at death | |

| Hospice/home hospice | 81% (13) |

| Hospital | 13% (2) |

| Nursing home | 6% (1) |

| Long-term ventilation in use |

|

| Yes | 0% (0) |

| BIPAP in use | |

| Yes | 56% (9) |

| No | 44% (7) |

| Forced expiratory volume (FEV) | Range 16–94, M = 51.69 (SD = 22.55) |

| Patient age | Range 41–83, M = 65 years (SD = 11.56) |

Table 2.

Types of decisions reported by patients before death and families near death (N = 16)

| Decision type | Patients % (n) | Family % (n) | Examples of topics within decisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where or from whom to seek care | 37% (6) | 0 | Choosing a neurologist and an ALS center, whether to go to assisted living facility |

| Treatment of symptoms/illness | 19% (3) | 13% (2) | Whether to undergo endoscopy/other screenings |

| Life-sustaining treatments | 19% (3) | 31% (5) | Whether to begin ventilator support |

| Feeding/eating | 19% (3) | 13% (2) | Whether to have a PEG/feeding tube, whether to change eating habits |

| No decision made | 6% (1) | 6% (1) | |

| Palliative care/hospice | 0 | 25% (4) | Whether to begin home hospice |

| Funeral planning | 0 | 13% (2) | Wanted to plan funeral |

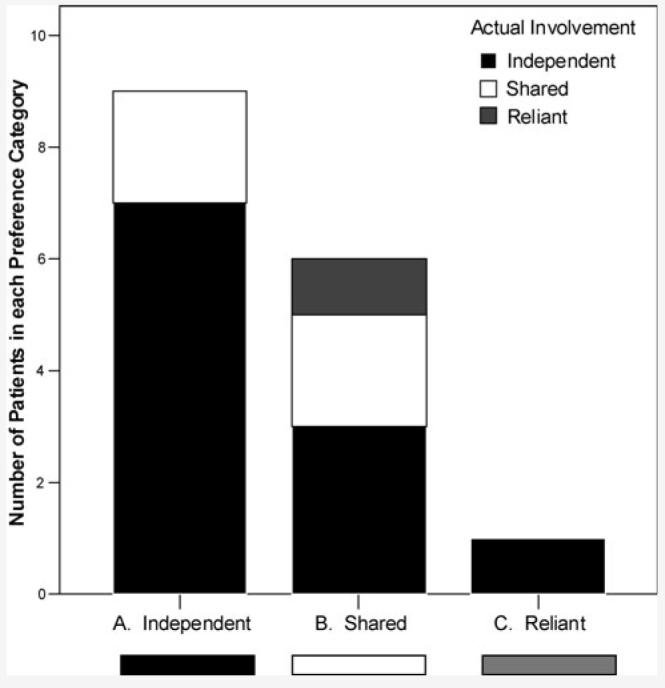

Figure 1. depicts the style of family involvement for which the patients opted and the actual family involvement as reported by family members. The height of the bars represents the number of patients opting for each of the roles for family involvement displayed along the x axis (independent of family, shared with family, or reliant on family). The shading within the bars represents the actual involvement of family in health care decision making near death as reported by family after the patient's death. The match between preferred and actual family involvement was not significant at kappa = .152 ( p = .46). As can be seen, the actual involvement of the family was concordant with the patients' preferences in 7/9 (78%) of cases if the patient preferred an independent style, 3/6 (50%) if the patient preferred shared decision making, and 0/1 (0%) if the patient preferred to rely on the family's judgment.

Fig. 1.

Preferred family decision involvement and actual involvement. A: Of the nine who preferred independent decision making, seven achieved it. B: Of the six who preferred shared decision making, two achieved it. C: The one who preferred to rely on family decision making did not achieve this.

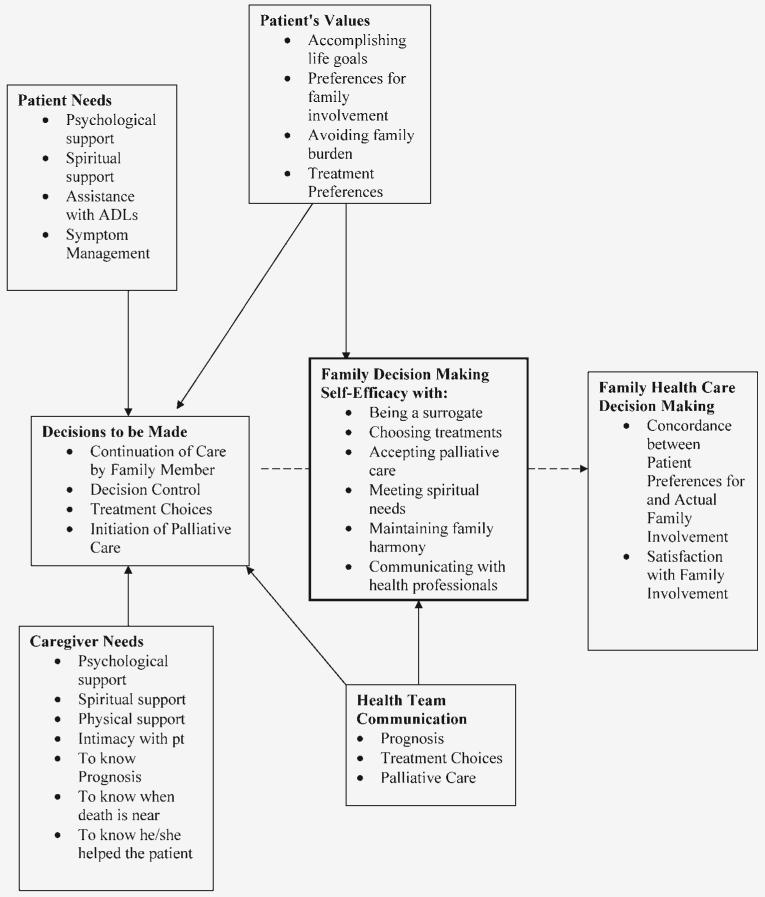

Table 3 summarizes the concordance of patient preferred decision control and actual control reported by family in the qualitative subsample. The in-depth qualitative interviews with these individuals revealed seven factors involved in family health care decision making at the end of life. These are summarized below. The relationship among the factors is depicted in the framework in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Concordance of patient preferred decision control and actual control reported by family in qualitative subsample (n = 5)

| Concordance | Family member |

Preferred | Actual |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, independent | husband | independent | independent |

| Yes, independent | wife | independent | independent |

| No, pt. more reliant | daughter | shared | reliant |

| No, pt. more independent | male significant other | reliant | independent |

| Yes, shared | wife | shared | shared |

Fig. 2.

Framework of family end-of-life health care decision making.

Patient Needs

These were patient requirements for care that the family member identified as influencing what patient care decisions needed to be made. They included the need for psychological support, spiritual support, assistance with activities of daily living, and assistance with managing symptoms. Common symptoms reported as troublesome were muscle weakness, shortness of breath, and lack of appetite. Three family members described being very concerned about the patient's lack of appetite. Two worried that it indicated that the patient was giving up or trying to end life by declining to eat. The third worried that he was starving his wife to death by not trying hard enough to find food that she wanted to eat.

Caregiver Needs

These were family member requirements that family members indicated influenced what patient care decisions needed to be made. In every case in this study, the family member we interviewed was the primary caregiver. They expressed the need for psychological support, spiritual support, physical support, intimacy with the patient, knowing the prognosis, knowing when death is near, and knowing that he/she helped the patient. An example of how a caregiver's need influenced the decision to be made about patient care involved a device needed to lift and move the patient. Two family members mentioned the assistive device, the Hoyer lift. One woman reported that she could not have cared for her mother at home without this. Another woman reported that the lift was dropped off at her house by the equipment delivery man but that no one showed her how to use this to care for her husband so, initially this equipment was another source of stress rather than a method of decreasing the stress of caregiving. The need to feel helpful to the patient was a commonly expressed need. One man asked the home care nurse if he could change the dressings on his wife's pressure sores because he liked knowing that he was helping her in this way. He was grateful that the home health nurse showed him how to do this and recounted that the nurse praised and encouraged him in his caregiving efforts.

Decisions to Be Made

These were critical decisions that needed to be made about the patient's care. These decisions included the continuation or cessation of care by the family caregiver, the extent to which the patient would be involved in health care decision making, the treatment choices available, and the initiation of palliative care. For example, one man recounted that his wife asked to be moved from their home to the hospital in the last days of her life although he wanted her to remain at home. She convinced him that caring for her had become too much for him. Another patient had issued an advance directive stating that he wanted no artificial treatments. His wife reported however, that he changed his mind about accepting a feeding tube in the hopes that it would provide him with more energy up to the end of his life.

Patient Values

These were the deeply held beliefs or values held by the patient. The patient values discussed by family members were the sense of accomplishing life's goals, the desired involvement of family in decisions, and the desire to avoid burdening the family. This concern was particularly strong. For example, one man explained that his wife feared that she would die just before Christmas and made her husband promise that he would not tell their grandchildren until after Christmas to avoid saddening them during the holiday. The same man reported that when his wife became concerned that he would become depressed and suicidal, she contacted her pastor and the home health nurse who intervened immediately to support the husband.

Health Team Communication

These were the verbal and nonverbal messages that family members described that they received from members of the health care team. Family members described receiving information about the patient's prognosis, treatment choices, and the recommendations regarding palliative care. They experienced these messages both positively and negatively. For example, one man commented that he pressed his wife's physician to tell him whether she was dying but thought that the physician was unable to say this to him. Another man thought that a home health nurse had been too abrupt in revealing the patient's terminal condition by pressing the patient for her preference on whether she preferred to die at home or in the hospital. The same man praised one of the nurses in the ALS clinic for “treating us like persons, not patients.”

Family Decision Making Self-Efficacy

This is the extent to which family members felt confident in making decisions with or for the patient. This included the family members' confidence that they could help the patient to make decisions that were best for him/her. This also included their confidence in making decisions about how the patient would receive food and fluid, treatment for pain, and resuscitation. How confident the family member felt in helping the patient to make decisions about palliative care, meeting spiritual needs, maintaining family harmony, and talking with doctors, nurses, and others about health needs of the patient were other important aspects of this concept. For example, the husband of one patient had lost his first wife to cancer. He explained that the experience of his first wife's death helped him to be more straightforward in asking his wife's physicians about her prognosis and treatments. He also was satisfied that he had encouraged his stepsons' visits to his second wife at the end of life because he had experienced with his first wife that death can come unexpectedly soon.

Family Health Care Decision Making

This is the final outcome of the process of family health care decision making. It included the concordance between the desired and actual family involvement in health care decision making and the family member's satisfaction with the level of involvement achieved. Patients indicated the extent to which they wished to involve their family in their decision making without difficulty. In the interviews after the death of the patient, family members were able to describe how decisions were made and often commented that this is the way they had always made decisions or that this is the way the patient had wanted to make these decisions. For example, the wife of one patient explained that he had written out his wishes about tube feedings and hospice because he did not want her to have to make these decisions. Only one woman expressed a great deal of dissatisfaction with decision making as well as many other aspects of her husband's illness and death. Although she reported that her husband made independent decisions, which was his preference, she said that sometimes she had to become “the boss” and place limits on his demands for her time and energy in caring for him. The same woman also reported emotionally that she simply did not have enough help from family or the health professionals caring for her husband.

DISCUSSION

The most significant finding of this study is that patients who preferred an independent style of decision making were most likely to achieve this whereas only two of the seven who desired either shared decision making or would defer to family achieved this. Our qualitative data might help to explain why patients who preferred shared or decision making that relied upon family were less likely to achieve this wish than those who preferred independent decision making. These data suggest the possibility that family members were so distressed that it was easier for them to defer to the patient than to participate in decision making. In-depth interviews revealed that family members variously felt deep distress, exhaustion, and depression regarding health care decision making and other aspects of caregiving at the end of their family member's life. This is consistent with a study of ALS caregivers by Krivickas et al. (1997) in which nearly half of the caregivers whose family member was receiving home care reported feeling physically and psychologically unwell.

Another possible reason for patients not achieving their desire for shared decision making or decision making that is reliant on a family member is related to advance directives. In this study most patients (87%) had issued an advance directive. Advance directives privilege an independent decision making style based upon respect for autonomy. Family members may have erroneously concluded that the independent decision making model on which these documents are based is the only acceptable decision making model. Therefore, they may have avoided shared decision making with the patient when asked to do so by the patient. Alternately, they may have shared decision making with the patient and reported to us that they did not, reflecting a social acceptability bias.

Another possibility is that family members did not wish to be associated with a decision that was not supported by other family members. One woman had expressed her fear of being seen as killing her husband by his other family members if her caregiving was judged to be inadequate. In a study by Martin and Turnbull (2001), 15% of the caregivers felt blamed by in-laws for contributing to the death of the person with ALS. A final possible explanation for family members' reporting that decisions had been made independently by the patient despite the patient's previously stated preference for shared decision making is that family members may have so closely identified with the patient that a shared decision was reported by the family as an independent patient decision. In this study and in another study of family members after the death of the patient (McSkimming et al., 1999), family members often used the term “our illness” and the term “patients” to refer to themselves and the patient.

Another important finding of this study was the multiple factors that family members described as part of the decision making experience. European Guidelines for the care of patients with ALS and their relatives recommend that clinicians include the patient and family in addressing several of these factors, such as symptom management, treatment choices, and the initiation of palliative care (Andersen et al., 2005). However, other factors mentioned by the family members in this study were not addressed. For example, the family members' need to know when death is near, the need to know that they have helped the patient, and the need for spiritual support in dealing with these end-of-life decisions. The guidelines do not suggest that clinicians determine the extent to which patients want their family members to be involved in their health care decisions. The omission of this may be a problem for patients seeking to involve their family in decision making and for family members who may need support to fulfill this role.

CONCLUSION

Several limitations restrict the generalizability of our findings. First, all patients were being treated in a teaching hospital, nearly all were white, the majority were cared for by spouses, and the majority of patients died in a hospice institution or were receiving hospice care at home. So, this sample may not be representative of the larger community of patients with ALS and their family members. Also, the sample of this study was small. However, the use of qualitative interviews in addition to our quantitative data allowed us to explore the family experience of decision making in depth in a multimethod manner that has not been previously reported in the literature on the care of patients with ALS.

These findings suggest several implications for practice. Clinicians who care for patients with ALS should discuss with them the extent to which they wish to involve their families in decisions at the end of life. If the patient desires a shared decision making style with family, clinicians can encourage patients to discuss this desire with their family or can facilitate this discussion during appointments in which the patient involves family. If a family member fears being blamed for providing inadequate care by other family members, this can be discussed to see if the patient would like to discuss his wishes with other family members as a way of avoiding this conflict.

Further study is needed to explore the reasons associated with the lack of patient and family concordance in family participation in decision making at the end of life. A study with a larger sample may allow for the analysis of the impact of demographic and treatment variables on this outcome. We conducted a preliminary exploration of the family member's sense of self-efficacy in participating in decision making with their family member with ALS. Whether family self-efficacy can be influenced by health team communication and the family member's understanding of the patient's values should be studied further. Exploration is also needed regarding whether family self-efficacy serves to moderate the relationship between the decisions to be made about the patient's care and the outcomes of these decisions. Finally, additional study is needed to determine the strength of the relationship of the other factors identified by family members in this study as part of their decision making experience and the outcomes of decision making. Because many patients in this study who desired shared family decision making did not achieve it, interventions might be developed to facilitate discussions by patients and families regarding the patient's desire for shared decision making and the family's response to this wish. Such interventions should be tested for their impact on decision making concordance between patients and their families and family satisfaction with the decision making at the end of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Jennifer Horner and Richard Kimball for their assistance with data collection. We also gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Institute for Nursing Research at the National Institutes of Health (1 R01 NR005224-01A1), the ALS Research Center of Johns Hopkins University, and the Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation through a grant administrated by Partnership for Caring.

REFERENCES

- Albert SM, Murphy PL, Del Bene ML, et al. A prospective study of treatment preferences and actual treatment choices in ALS. Neurology. 1999;53:278–283. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner LF, Sloan JA. Decision making during serious illness: What role do patients really want to play? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:941–950. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PM, Borasio GD, Dengler R, et al. EFNS task force on management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Guidelines for diagnosing and clinical care of patients and relatives. European Journal of Neurology. 2005;12:921–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkinjuntti T, Sulkava R, Wikstrom J, et al. Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire as a screening test for dementia and delirium among the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1987;35:412–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzini L, Johnston WS, Silveira MJ. The final month of life in patients with ALS. Neurology. 2002;59:428–431. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113:941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivickas LS, Shockley L, Mitsumoto H. Home care of patients with amyotrophic laternal scierosis (ALS) Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1997;152(Suppl 1):S82–S89. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Turnbull J. Lasting impact in families after death in ALS. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders. 2001;2:181–187. doi: 10.1080/14660820152882188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSkimming S, Hodges M, Super A, et al. The experience of life-threatening illness: Patients and their loved ones perspectives. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 1999;2:173–184. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss AH, Oppenheimer EA, Casey P, et al. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis receiving long-term mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1996;110:249–255. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MT, Hughes M, Narandra DP, Sood JR, Terry PB, Astrow AB, et al. When patients lack capacity: The roles that patients with terminal diagnoses would choose for their physicians and loved ones in making medical decisions. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;30:342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajares F. Overview of social cognitive theory of self-efficacy. 2002 Available at www.emory.edu/EDUCATION/mfp/eff.html. Retrieved Feb. 25, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer E. A Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1975;23:433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-methods studies. Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:246–255. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200006)23:3<246::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]