Abstract

HexaPEGylated Hb, a non-hypertensive Hb, exhibits high O2-affinity which makes it difficult to deliver desired levels of oxygen to tissue. PEGylation of very low O2-affinity Hbs is now contemplated as the strategy to generate PEGylated Hbs with intermediate levels of O2-affinity. Towards this goal, a doubly modified Hb with very low O2-affinity has been generated. The amino terminal of β-chain of HbA is modified by 2-hydroxy, 3-phospho propylation first to generate a low oxygen affinity Hb, HPPr-HbA. The oxygen affinity of this Hb is insensitive to DPG and IHP. Molecular modeling studies indicated potential interactions between the covalently linked phosphate group and Lys-82 of the trans β-chain. To further modulate the oxygen affinity of Hb, the αα-fumaryl crossbridge has been introduced into HPPr-HbA in the mid central cavity. The doubly modified HbA (αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA) exhibits an O2-affinity lower than that of either of the singly modified Hbs, with a partial additivity of the two modifications. The geminate recombination and the visible resonance Raman spectra of the photoproduct of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA also reflect a degree of additive influence of each of these modifications. The two modifications induced a synergistic influence on the chemical reactivity of Cys-93(β). It is suggested that the doubly modified Hb has accessed the low affinity T-state that is non-responsive to effectors. The doubly modified Hb is considered as a potential candidate for generating PEGylated Hbs with an O2-affinity comparable to that of erythrocytes for developing blood substitutes.

Developing low O2-affinity Hb has been the subject of considerable interest both in terms of understanding the structure-function correlation of Hb and for the development of Hb based oxygen carriers. Central cavity modifications such as crosslinking and affinity labeling of the effector binding domains of Hb has been the prominent approaches to reduce the O2-affinity of Hb (1-6). However, interest in such molecules subsides since most of these potential Hb based oxygen carriers turned out to be vasoactive (7-9). The vasoactivity was considered to be a consequence of the NO scavenging activity of acellular Hb (10-12). Design of mutant Hbs with reduced NO binding activity has been one of the approaches advanced to generate nonhypertensive Hb based oxygen carriers (11, 13-15).

An alternate approach to overcome the vasoactivity of Hb advocates the induction of unique molecular properties of plasma volume expanders such as colloid osmotic pressure and viscosity into Hb. Conjugation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to Hb appears to achieve this goal (16-19). Our recent observation that surface decoration of Hb with six copies of PEG-5000 chains nearly neutralizes the vasoactivity of Hb validates the concept that PEGylation of Hb can be used as a way of generating nonhypertensive Hb (19). Accordingly we have generated PEGylated Hb employing different chemistry, thiolation-mediated maleimide chemistry (19-20), reductive alkylation (21), acylation and thiocarbamoylation (22). All these modifications were directed to amino groups of Hb. The resultant PEGylated Hbs had an average of six copies of PEG chains conjugated at different sites of Hb. All these PEGylated Hbs had an increased O2-affinity, irrespective of the chemistry of modification and sites of PEG conjugation (19-21).

Though high O2-affinity of the PEGylated Hbs is considered as an advantageous factor in achieving the neutralization of the vasoactivity of Hb by reducing the amount of oxygen delivered on the arterial side of the microcirculatory system (18, 23-25), the O2-affinity of the present versions of PEGylated Hbs appears to be too high to deliver adequate levels of oxygen to tissues. Accordingly, we have been considering the use of low O2-affinity Hbs instead of using normal adult human Hb as substrates for the generation of PEGylated Hbs using the same protocols discussed above (19-22).

Our recent studies of hexaPEGylation of αα-fumaryl Hb have generated a PEGylated Hb (26) with an oxygen affinity (P50 ∼14 mm of Hg) lower than that of hexaPEGylated Hb (P50 ∼7 mm of Hg). HexaPEGylation of modified Hbs, with an oxygen affinity still lower than that of αα-fumaryl Hb, may be expected to facilitate the generation of very low oxygen affinity that is comparable to that of erythrocytes (P50 ∼28 mm of Hg). Preparation of doubly modified Hbs is an approach to generate very low oxygen affinity Hbs that could be used as substrates for PEGylation to generate low oxygen affinity PEGylated Hbs.

Introduction of negative charges at the amino terminal of β-chain induces low oxygen affinity to Hb (4, 27-28). While carboxymethylation (4) and galacturonic acid (27) modification introduce a carboxyl group at Val-1(β), pyridoxal phosphate modification (28) adds a phosphate group at the same site. The influence of pyridoxal phosphate in reducing the oxygen affinity of Hb seems to be higher than carboxymethylation or galacturonic acid modification at Val-1(β), presumably due to the presence of a phosphate group. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is similar to DPG in structure and site specific modification of Val-1(β) of Hb by this reagent will introduce two phosphate groups in the DPG binding site of Hb. This can induce low oxygen affinity to Hb similar to DPG. Therefore, in the present study, we have explored the use of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the presence of sodium cyanoborohydride to modify the α-amino group of Val-1(β). This reaction is carried out under oxy conditions as compared to the deoxy conditions used for the modification of Hb by pyridoxal phosphate (28).

The αα-fumaryl crossbridging in the mid central cavity of HbA is another structural modification that reduces the O2-affinity of HbA. The reagent, bis dibromosalicyl fumarate (DBBF), introduces a crosslink between the ε-amino groups of Lys-99(α) of the central cavity only in the deoxy conformation (5). Under oxy conditions, the same reagent introduces a crosslink between the ε-amino groups of Lys-82(β) residues of ββ-cleft and induces a high O2-affinity to HbA (3). The high conformational selectivity of the reaction of DBBF with HbA and the resulting distinct influence of the crosslinking on the O2-affinity has been interpreted as the consequence of freezing in the oxy or deoxy conformation of the protein through crosslinking (5, 29). These crosslinking reactions have been used to stabilize the 1 2 interface that is weakened by structural modifications of Hb (26, 30).

Introduction of more than one low O2-affinity inducing chemical modifications into Hb, generating a doubly modified Hb, is the approach that we have been considering to develop a very low O2-affinity Hb. These chemical modifications may act additively or synergistically to generate a very low O2-affinity Hb. Recently, we have engineered the αα-fumaryl crossbridge into Hb Presbyterian (Hb-P), a low O2-affinity mid central cavity mutant Hb (31). The αα-fumaryl Hb-P exhibited a very low O2-affinity. The two structural modifications, i.e. the Presbyterian mutation (Asn-108(β)→Lys), and αα-fumaryl crossbridging, exhibited a synergy in reducing the O2-affinity of the molecule. Since the two structural modifications in this case were in the mid central cavity, the proximity of the two structural perturbations might have facilitated the synergy of the two modifications of Hb structure.

In an attempt to generate a very low oxygen affinity Hb by chemical modifications, we have now introduced the mid central cavity low oxygen affinity inducing αα-fumaryl crossbridge into HPPr-HbA. Characterization of the doubly modified HbA and correlation of its oxygen binding properties, geminate rebinding, conformation of heme pocket in the R-state, and Cys-93(β) reactivity are presented in this study. These results are discussed in the light that R-state conformation of Hb represents a dynamic equilibrium between multiple R-state conformations. The linkage of the low O2-affinity inducing perturbation of the mid central cavity with that of ββ-cleft is only additive and is distinct from the linkage of two mid central cavity perturbations studied earlier (31). The possible application of these very low O2-affinity Hbs in the generation of non-hypertensive lower oxygen affinity PEGylated Hbs is also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of HPPr-HbA

Purified HbA (0.5 mM) was modified with 5 mM glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the presence of 10 mM NaCNBH3 in PBS, pH 7.4, at 37°C for 30 min. The product, HPPr-HbA, was purified on CM-52 cellulose (2.5 × 50 cm) using a gradient of 10 mM phosphate, pH 6.0 to 15 mM phosphate, pH 8.0. The peak corresponding to HPPr-HbA, as characterized by the isoelectric focusing of the peak, was further purified on the same column, using a shallower gradient.

Cross-linking of HPPr-HbA by DBBF

HPPr-HbA was modified with DBBF as described previously (5). Briefly, HPPr-HbA (1 mM) was incubated with 8 mM sodium tripolyphosphate overnight at 4°C to prevent the modification of DPG pocket residues by DBBF. This sample was deoxygenated at 37°C and incubated with 2 mM DBBF at the same temperature for 4 h. The reaction was stopped by adding 20 mM Gly-Gly.

Analysis of αα-fumaryl crosslinking of HPPr-HbA

This analysis was carried out by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (RPHPLC) using a Vydac C4 column (4.6 × 250 mm). The same amount of hemoglobin samples were loaded in 0.3% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) on C4 column equilibrated with 35% acetonitrile (ACN) containing 0.1% HFBA. The globin chains were eluted with a gradient of 35−45% ACN in the first 10 min and then 45−50% ACN in 90 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. HFBA (0.1%) was present in the solvents throughout the gradient.

Purification of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA

On introducing αα-fumaryl-crosslinking into HPPr-HbA, the derivative developed some met Hb. Therefore, the derivative was reduced with dithionite as described by Roy and Acharya (32). The oxy form of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was purified on Q-Sepharose High Performance (0.9 × 30 cm). The column was equilibrated with 50 mM Tris acetate, pH 8.0 and eluted with a linear gradient consisting of 200 ml each of buffer A (50 mM Tris acetate, pH 7.7) and buffer B (50 mM Tris acetate, pH 6.8 containing 25 mM NaCl).

Isoelectric focusing (IEF) of modified hemoglobins

Hemoglobin samples were analyzed on precast IEF agarose gels (PerkinElmer) containing resolve ampholytes pH 6−8. The gel was elctrofocused (Isolab) for 1h.

Mass spectrometry

The isolated globins of the modified Hbs were analyzed by ESI-MS on a 9.4 Tesla Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometer (Varian, Inc.). The tryptic peptides of the globin chains were analyzed by LC/ESI-MS (33) using a C8 or C18 column (Vydac 1 × 50 mm). A stepwise gradient using 5% ACN containing 0.1 % TFA as solvent A and 95% ACN containing 0.1 % TFA as solvent B was generated to separate the peptides.

O2-affinity measurements

The oxygen equilibrium measurements of modified Hbs were made at an Hb concentration of 0.5 mM, 37°C in 50 mM Bis-Tris/ 50 mM Tris acetate, pH 7.4, using Hem-O-Scan (AMINCO). The measurements were made in the absence and presence of allosteric effectors at the concentrations indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Oxygen affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA and its modulation by allosteric effectors

| Effector | HbA | HPPr-HbA | αα-fumaryl-HbA | αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 7.7(2.6) | 24.5(2.1) | 24.0(2.5) | 48.5(1.8) |

| 2.5 mM DPG | 19.5(2.1) | 26.0(1.8) | 45.0(2.0) | 49.0(1.7) |

| 2.5 mM IHP | 70.8(1.4) | 28.5(1.9) | 92.0(1.0) | 48.5(1.7) |

| 2.5 mM L35 | 63.0(1.3) | 78.0(1.4) | 48.5(1.9) | 77.0(1.1) |

| 1.0 M NaCl | 24.0(2.3) | 36.0(2.0) | 39.5(2.0) | 51.5(1.8) |

| 0.1 M NaCl | 13.0(2.4) | 30.0(2.0) | 29.5(2.1) | 50.0(1.6) |

Hill coefficient is given in parenthesis.

In the measurements with P50 higher than 60 mmHg, Hb samples were not 100% oxygenated.

These are some of the samples with IHP and L-35. In these cases cooperativity is also low.

Therefore, the oxygenation values of Hbs at the maximum pO2 (178 mmHg) were considered as 100% saturation in these experiments to determine the P50 values. These approximations under estimate the P50 values calculated.

Reactivity of Cys-93(β) of modified Hbs

The reactivity of Cys-93(β) of modified Hbs was determined by the reaction of Hb with 4,4’-dithiodipyridine (4-PDS) as described by Ampulski et al. (34). Typically, carbonmonoxy form of Hb (5 uM) was added to 50 uM 4-PDS in 50 mM Bis-Tris/Tris acetate, pH 7.4, at 30°C. The reaction kinetics was followed by monitoring the formation of the reaction product of 4-PDS, 4-thiopyridone, at 324 nm. The number of titrable thiol groups of Hb was determined from the initial concentration of Hb and the concentration of 4-thiopyridone formed at the end of the reaction.

Geminate Binding Studies

Geminate recombination of carbonmonoxide to 10μs photoproducts of carbonmonoxy forms of HbA and modified Hbs was determined as described by Khan et al (35). All the samples used for the kinetic measurements were at 0.5 mM in heme in 50 mM Bis-Tris acetate, pH 6.5, at 3.5°C.

Visible Resonance Raman Studies

Visible RR spectra were generated for the 8 ns photoproducts of the CO derivatives of HbA and modified Hbs at 0.5 mM in heme in 50 mM Bis-Tris acetate, pH 6.5, at 3.5°C (35).

Molecular Modeling

The high resolution crystal structure of hemoglobin, protein data bank code 4HHB (36) was chosen for initial model. The molecular model of αα-fumaryl cross-linked Hb was built as described by Chatterjee et al. (5). The fumaryl chain was modeled using the builder module of Insight II® computer graphics (Accelrys Software Inc). The dihedrals of the side chains of both Lys-99 (α) were modified without affecting the main chain configuration such that a covalent fumaryl linkage is feasible between the two side chains. The backbone was kept intact and the lysine side chains were extended to accommodate the fumaryl linkage (5). The modeling was done to have symmetric linkage with out Van der Waals overlap between the atoms of new group with the existing atoms of hemoglobin. The modified dihedral angles were also within reasonable limits.

The low resolution crystal structure protein data bank code 1B86 (37) was chosen for HPPr-HbA modeling. This deoxy structure contains the DPG. This would enable us to position the phosphates of HPPr group close to the DPG phosphate groups. The HPPr group linkage was modeled using both the builder module and biopolymer module. Efforts were made to bring the two phosphate groups close to the position of the phosphate groups of DPG bound within the ββ-cleft with no Van der Waals overlap. The dihedral angles were also within reasonable limits.

RESULTS

Preparation and Characterization of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA

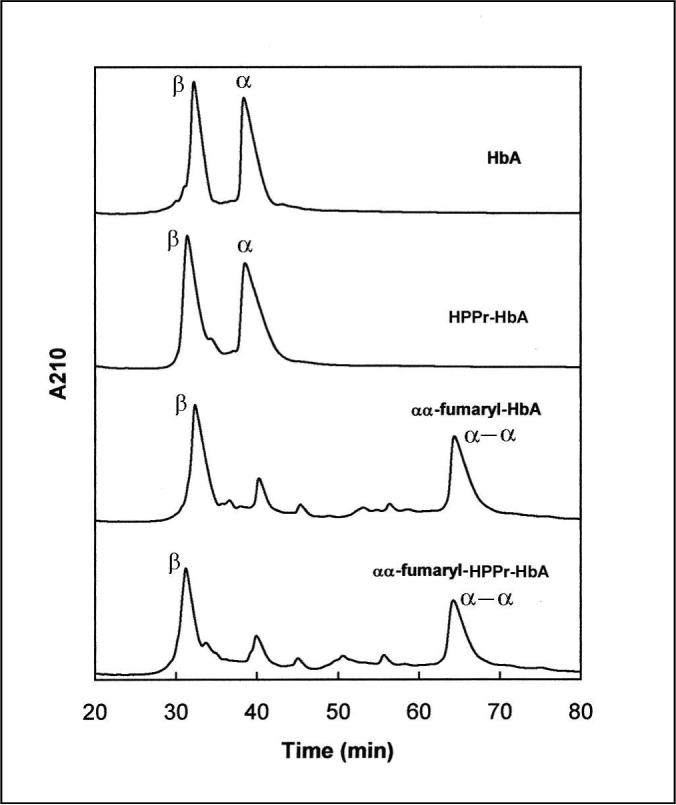

The reactivity of HPPr-HbA to undergo αα-fumaryl cross-linking with DBBF under the conditions used for HbA was established by globin chain analysis of the reaction products by RPHPLC. As can be seen in Figure 1, the RPHPLC profiles of the two reaction products are quite comparable and consist of uncross-linked β-globin and cross-linked α-globin as the two major products. These results indicated that the extent of cross-linking of HPPr-HbA by DBBF was comparable to that of HbA as reflected by the formation of αα-fumaryl globin (Fig. 1). The HPPr modification of Hb did not alter the reactivity of Lys-99(α) to form αα-fumaryl cross-linking.

Fig. 1.

RPHPLC of modified hemoglobins. The same amount of hemoglobin samples were loaded in 0.3% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) on Vydac C4 column (4.6 × 250 mm) equilibrated with 35% acetonitrile (ACN) containing 0.1% HFBA. The globin chains were eluted with a gradient of 35−45% ACN in the first 10 min and then 45−50% ACN in 90 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. HFBA (0.1%) was present in the solvents throughout the gradient.

αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was purified by chromatography on Q-Sepharose High Performance. There were two major peaks in the chromatogram, labeled as Peak-1 and Peak-2 (Fig. 2). The IEF analysis of the peaks is shown in Fig. 2 inset. Peak-1 is homogeneous (Inset in Fig. 2, Lane 4) whereas Peak-2 is heterogeneous containing products that are more acidic than the Peak-1 component (Lane 5). Presumably, these are the products modified by DBBF at multiple sites. The fainter bands, in Peak 1, corresponding to minor products accounted for less than 5%. Therefore, Peak 1 was selected for all the further studies without further purification.

Fig. 2.

Purification of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA on Q-sepharose High Performance (0.9 × 30 cm). The column was equilibrated with 50 mM Tris acetate, pH 8.0 and eluted with a linear gradient consisting of 200 ml each of buffer A (50 mM Tris acetate, pH 7.7) and buffer B (50 mM Tris acetate, pH 6.8 containing 25 mM NaCl). The arrows indicate the fractions pooled from the peaks 1 and 2. Inset: IEF of modified hemoglobins: Lane1, HbA; Lane 2, αα-fumaryl-HbA; Lane 3, HPPr-HbA; Lane 4 and 5, Peaks 1 and 2 from Q-sepharose chromatography of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA, respectively. The + and − signs indicate the positions of the anode and cathode during electrofocusing.

The IEF profile of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was compared with those of HbA, αα-fumaryl-HbA, and HPPr-HbA (Fig. 2, inset). As can be seen, HPPr-HbA (Lane 3) exhibited a lower isoelectric point than HbA (Lane 1). This is primarily due to the introduction of the negatively charged phosphate group at Val-1(β) and also due to the lowered pKa of the α-amino group of Val-1(β) as a result of its conversion into a secondary amine. In contrast, the isoelectric point of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA (Lane 4) is comparable to that of HPPr-HbA (Lane 3), despite the loss of the positive charges of two of its ε-amino groups due to the introduction of the αα-fumaryl crosslinking. This phenomenon is similar to that observed with the αα-fumaryl crosslinking of HbA (Lanes 1 and 2), a result consistent with the earlier reports (5).

The two globin chains of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA were analyzed by ESI mass spectrometry (Table 1). The mass of β-chain indicated that each β-chain is conjugated to only one HPPr moiety and no DBBF modification of the β-chain has taken place. On the other hand, the mass of the α-component established the crosslinking of two α-chains by only one fumaryl group and no signs of HPPr conjugation.

Table 1.

The mass of globin chains of Hbs determined by ESI mass spectrometry

| Molecular mass (Da) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-component | β-component | |||

| Sample | Calculated | Measured | Calculated | Measured |

| HbA | 15126.4 | 15129.0 | 15867.2 | 15866.0 |

| HPPr-HbA | 15126.4 | 15129.0 | 16021.3 | 16020.0 |

| αα-fumaryl-HbA | 30332.8 | 30330.0 | 15867.2 | 15868.0 |

| αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA | 30332.8 | 30330.0 | 16021.3 | 16020.0 |

To further characterize the sites of modification in the doubly modified Hb, the modified alpha and beta globins were digested with trypsin and the tryptic peptides were analyzed by LC/MS. The masses of all the peptides of the modified β-globin matched with that of the control β-globin, except for one peptide that corresponded to the residues 1 to 8 of β-chain. The peptide 1−8 carried an excess mass of 154 Da than the control peptide (Fig 3A). This mass corresponds to the mass of HPPr moiety that has been conjugated to the β-globin. This establishes that G3P has modified the amino terminal of β-chain, site specifically in the doubly modified Hb.

Fig. 3.

A) Mass spectrum of the G3P modified peptide of β-globin from αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. The mass of this peptide corresponds to HPPr conjugated to the peptide comprising residues 1−8 of β-globin.

B) Mass spectrum of the fumaryl cross-linked peptide of the crosslinked α-globin from αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. The mass of this peptide corresponds to two copies of peptide spanning the residues 93−127 of β-globin cross-linked by a fumaryl group. The absence of cleavage at Lys-99(α) by trypsin is apparently a consequence of the covalent attachment of the ε-amino group of this residue to fumaryl moiety.

A comparison of the masses of the tryptic peptides of the modified α-globin with that of the control revealed the appearance of a new peptide carrying a mass of 7612.056 Da (Fig 3B). This mass matched with the contiguous segment 93−127 of α-globin cross-linked by a fumaryl group. Thus, αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA carries an HPPr moiety at the amino terminal of β-chain and a fumaryl crosslink at Lys-99 of the α-chains.

Functional studies of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA

The O2-affinity of HbA was lowered nearly to the same degree by both of the modifications studied. The O2-affinity of HPPr-HbA and αα-fumaryl-HbA were about three times lower than that of HbA. The O2-affinity of the doubly modified HbA, αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA, was about six fold lower than that of HbA (Table 2). Thus, αα-fumaryl crosslinking reduced the O2-affinity of HbA 3-fold and that of HPPr-HbA only 2-fold. Therefore, the influence of HPPr modification and of αα-fumaryl crosslinking of HbA on its O2-affinity appears to be partially additive. The lowering of the O2-affinity was accompanied by a small reduction in the Hill coefficient.

Modulation of the O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA by Allosteric Effectors

The O2-affinity of the Hb derivatives has been studied in the presence of 0.1 M and 1.0 M NaCl. The derivatives with single modification, HPPr-HbA as well as αα-fumaryl-HbA have retained some sensitivity to the presence of chloride, nearly to the same extent (Table 2). On the other hand, the O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was insensitive to the presence of chloride, reflecting the additivity of chloride mediated reduction in the O2-affinity of the two modifications. It may also be noted that the O2-affinity of both HPPr-HbA and αα-fumaryl-HbA in the absence of chloride was comparable to that of HbA in the presence of 1.0 M chloride. The O2-affinity of the two modified Hbs could be reduced further by 1.0 M chloride. The electrostatic modification of either of ββ-cleft or of the mid central cavity increases the propensity of Hb to access lower O2-affinity conformation in the presence of chloride. The insensitivity of the doubly modified Hb to chloride suggests that the modulation of the O2-affinity by the positive charge density of the central cavity has been completely neutralized by the presence of the two modifications.

The O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was not influenced by the presence of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (DPG) (Table 2). The O2-affinity of HPPr-HbA was also insensitive to the presence of DPG. HPPr modification of Hb makes the molecule insensitive to the presence of DPG. The intrinsic O2-affinity of HPPr-HbA was lower than that of HbA in the presence of DPG. Similarly, the intrinsic O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was lower than the DPG modulated O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HbA. The covalent attachment of phosphate group at the DPG pocket seems to stabilize the T-structure of tetramer better than the physiological modulator, DPG.

Although inositol hexaphosphate (IHP) is a stronger modulator of the O2-affinity of HbA, like DPG, it had negligible effect on the O2-affinity of HPPr-HbA and αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. In contrast, IHP reduced the O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HbA to a level greater than that observed with HbA. Thus, HPPr modification essentially desensitizes the influence of IHP to modulate the O2-affinity of HbA as well as of αα-fumaryl-HbA.

The effect of the allosteric effector 2-[4-(3,5-dichlorophenylureido)phenoxy]-2-methylpropionic acid (L35) that binds at the αα-end of the central cavity (38) is quite opposite to that of DPG and IHP that bind at the ββ-cleft. L35 reduced the O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA to a level lower than that of HbA (Table 2). The intrinsic P50 of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was comparable to that of HPPr-HbA in the presence of L35. The O2-affinity reducing potential of HPPr modification and that of L35 appears to act additively on HbA and on αα-fumaryl-HbA. This additivity is consistent with the report that the O2-affinity reducing potential of DPG and/or IHP and that of L-35 are additive (38). On the other hand, αα-fumaryl crosslinking of HbA reduced the propensity of L35 to lower the O2-affinity of HbA. The HPPr modification of αα-fumaryl-HbA overcomes the inhibitory activity of αα-fumaryl crossbridging on the L35 mediated reduction in the O2-affinity of HbA.

Geminate recombination studies

The geminate recombination of CO to photodissociated products of modified Hbs was determined to understand the structure of the initial population of the derivatives in R state (39-44). The geminate yield of HPPr-HbA and αα-fumaryl-HbA was about 12 and 8% lower than of HbA (Table 3). The geminate yield of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was 20% lower than that of HbA, indicating that the two modifications made an additive impact on the structure of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. The geminate yield of HPPr-HbA was insensitive to IHP and lowered by L35. In contrast, the geminate yield of αα-fumaryl-HbA responded to IHP but was not influenced by L35. HPPr modification of αα-fumaryl-HbA neutralized the inhibitory influence of αα-crosslinking on L35 modulation, as was seen with the O2-affinity.

Table 3.

Percentage of geminate yield of modified Hbs

| Hb | No effectors | +IHP | +L35 | +IHP+L35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA | 65 | 45 | 60 | 40 |

| HPPr-HbA | 57 | 57 | 52 | 52 |

| αα-fumaryl-HbA | 60 | 53 | 60 | 53 |

| αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA | 52 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

Hb concentration was 0.5 mM in heme.

IHP was added in 6 folds excess over tetramer concentration.

L35 was added in 4 folds excess over tetramer concentration.

Visible resonance Raman spectroscopy

Table 4 shows the influence of the chemical modification on the Fe-His stretching frequency of Hb, ν(Fe-His). It is clear that the correlation between the reduction in the frequency of ν(Fe-His) and that in GY is not operative across the board with respect to all the listed derivatives of Hb. Most notably the decrease in frequency was less for the HPPr modification than it was for the αα-fumaryl modification and yet the GY was lower for the former. The absence of an absolute one to one correspondence between the two parameters is likely to arise from either one or two factors. The frequency of ν(Fe-His) has been correlated with the contribution to the kinetic barrier at the heme due to proximal strain (39-40, 45-46). Proximal effects are claimed to be a bigger factor for the α subunits whereas distal effects are supposed to dominate the rebinding for the β subunits (47). Different modifications may impact the α and β subunits differently or have disparate effects on factors contributing to the GY, e.g. conformational mobility that facilitates ligand escape. Alternatively, as noted above, the relaxation of structure subsequent to photodissociation can influence the GY, whereas the given Raman frequency is reflective of the unrelaxed or minimally relaxed conformation. Differences in the GY could arise from differences in the conformational relaxation rates subsequent to photodissociation.

Table 4.

Iron-proximal histidine stretching frequency of modified Hbs

| Hb | No effectors | +IHP | +L35 | +IHP+L35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA | 230.0 | 228.0 | 228.5 | 225.0 |

| HPPr-HbA | 229.0 | 229.0 | 227.0 | 228.0 |

| αα-fumaryl-HbA | 227.0 | 225.5 | 226.0 | 224.0 |

| αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA | 226.0 | 226.0 | 225.3 | 226.0 |

All the values were given in wavenumber.

Hb concentration was 0.5 mM in heme.

IHP was added in 6 folds excess over tetramer concentration.

L35 was added in 4 folds excess over tetramer concentration.

Correlation between the O2-affinity of modified/mutant Hbs and the reactivity of their Cys-93(β) in the oxy conformation to form mixed disulfide with dithiodipyridine

Alterations in the O2-affinity of Hb has been suggested to correlate with changes in the reactivity of Cys-93(β) (48-53). In order to determine whether deoxy like conformational features of the modified Hbs are translated to the reactivity of Cys-93(β), thiol-disulfide exchange reaction of modified Hbs has been studied. The number of titrable thiol groups of the derivatives is listed in Table 5. The kinetics of the reaction of Cys-93(β) of these Hbs in their carbonmonoxy form with 4-PDS is shown in Fig 4. The rate of modification of Cys-93(β) of α-fumaryl-HbA was considerably lower compared to that of HbA. On the other hand, the HPPr modification of HbA did not influence the reactivity Cys-93(β) significantly. However, the reactivity of Cys-93(β) of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA was even lower than that of αα-fumaryl-HbA. Thus both the modifications together induced a synergistic influence on the reactivity of Cys-93(β).

Table 5.

Number of titrable thiol groups of modified Hbs

| Hb | Titrable thiol groups |

|---|---|

| HbA | 2.1 |

| HPPr-HbA | 2.2 |

| αα-fumaryl-HbA | 2.2 |

| αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA | 1.9 |

Fig. 4.

Kinetics of the reaction of modified hemoglobins with 4-PDS. Carbonmonoxy form of Hb (5 uM) was reacted with 50 uM 4-PDS in 50 mM Bis-Tris/Tris acetate, pH 7.4, at 30°C. The reaction kinetics was followed by monitoring the formation of the reaction product of 4-PDS, 4-thiopyridone, at 324 nm. • HbA, o HPPr-HbA, and ▲ αα-fumaryl-HbA, Δ αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA.

Molecular Models of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA

Fig 5A depicts the molecular model of doubly modified Hb. In the figure, the central cavity of the doubly modified Hb is viewed from the ββ-end of the central cavity to provide a comprehension of the positioning of the two central cavity modifications engineered into Hb to generate very low oxygen affinity molecule. In the model the α-chains are shown in red ribbons, and the β-chains in blue ribbons. The hemes are depicted in green color. The αα-fumaryl crossbridge is shown in magenta and the HPPr groups within the ββ-cleft are shown in cyan with the phosphate groups in red. The molecular models of singly modified Hbs have also been generated (data not shown), and these models have established that the presence of one modification has very limited influence on the structural changes induced into Hb by the other.

Fig 5.

Molecular model of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. (A) The model shows the location of the two covalent modifications in the central cavity viewed from the ββ-end of the central cavity. The α-chains are shown in red, the β-chains in blue and heme in green. Val-1(β) side chains are shown in orange and the HPPr groups are in cyan with their phosphates in red. Lys-99(α) side chains are in magenta and the fumaryl group is in green.

(B) Exploded view of the DPG binding pocket of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. The α-chains are shown in red and the β-chains in blue. The fumaryl crosslink is not shown for clarity. The positively charged centers of DPG pocket are shown in yellow with the side chains projecting out of the peptide back bone, except that Val-1(β) is shown in purple for clarity. The carbon chain of HPPr moiety is in cyan and its phosphate is in red. DPG is shown in the background in magenta to provide a feeling for the location of the phosphates of the covalently linked HPPr moiety relative to the phosphates of DPG. Internuclear distances from the closest negative charge centers of the phosphates to the positively charged centers of the DPG residues is provided.

The exploded view of the ββ-cleft of doubly modified Hb is shown in Fig 5B. The fumaryl crosslink is not shown for clarity. The model has incorporated the DPG in background in magenta to depict the location of the phosphate groups of DPG within positive charge dense DPG binding pocket of the molecule. The carbon chain of HPPr moiety is shown in cyan with the phosphate group being depicted in red. Val-1(β) is shown in purple. The phosphate group of HPPr covalently linked to the amino group of Val-1(β) occupies a position within the ββ-cleft that is very close to the position occupied by phosphate of DPG that is bound at the ββ cleft. The location of the peptide backbone of six positively charged residues of the DPG binding pocket that interact with DPG [His-2(β), Lys-82(β) and His-143(β)] are identified in the ribbon diagram by yellow and the side chains of these residues are also depicted. Internuclear distances between the negatively charged centers of phosphate and the positively charged centers of the protein in the DPG pocket of Hb that have been implicated to interact with the phosphate groups of DPG have been measured. The closest distances measured are shown in the figure (Fig 5B) and also summarized in Table 6. It is interesting to note that the negatively charged centers of phosphate of HPPr moiety linked to Val-1(β) could interact not only with the positive charge centers of cisdimers, bust also with those of the trans dimers. Therefore, the HPPr moieties covalently linked to Val-1(β) may be expected to function as the pseudo crosslinks to stabilize the interdimeric interactions of the molecule. Thus, the doubly modified Hb is an intramolecular crosslinked Hb, with a covalent cross-link between the α-chains and a psuedo crosslink between the β-chains.

Table 6.

Internuclear distances with in the ββ-cleft of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA

| Residues of Beta1 chain | Internuclear distance (Å) | |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate 1 | Phosphate 2 | |

| H2 | 4.2 (5.7) | 9.8 (7.6) |

| K82 | 5.0 (2.9) | 4.3 (4.2) |

| H143 | 7.4 (7.5) | 6.2 (6.5) |

Only the closest distance between the negatively charged centers of the phosphate of HPPr group and the positively charged groups of the DPG binding pocket (ββ-cleft) are given.

Internuclear distances for the opposite beta chain (beta2 chain) are given in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

The modification of HbA with G3P generated a low oxygen affinity Hb (HPPr-HbA) that is insensitive to DPG and IHP. The modulation of the oxygen affinity of Hb by the covalently attached HPPr group is comparable to that of pyridoxal phosphate in α2(βPLP)2 (28) and to a higher level than that by carboxymethyl group (4) or galacturonic acid (27) conjugated at Val-1(β). Thus, introduction of a phosphate group at this site seems to stabilize the low oxygen affinity conformation better than a carboxyl group. However, addition of a phosphate at Val-1(β) does not seem to be enough to exhibit such impact on the oxygen affinity of Hb. Affinity labeling of Val-1(β) with glucose-6-phosphate does not reduce the oxygen affinity of Hb (54) to the extent that is seen with G3P or pyridoxal phosphate. The structural features of these added groups seem to make major contribution towards this effect. In α2(βPLP)2 the two phosphates of the PLP groups take positions very close to the positions of the phosphates of DPG in deoxy Hb (55). Thus these phosphates can mimic the influence of DPG in stabilizing the deoxy state of Hb. G3P with similarities in structure with DPG, seems to exhibit similar impact on the oxygen affinity of Hb.

In order to understand the interactions of HPPr group with DPG binding site, we have carried out molecular modeling studies of deoxy HPPr-HbA (Fig 5). These studies indicated that the negative charges of the phosphate of the HPPr group can interact with the positive charge of Lys-82 of the cis as well as the trans β-chain of the modified Hbs (Table 6). In addition, interactions between His-2 of the cis β-chain and His-143 of the trans β-chain may also be possible. These interaction are comparable to the ones reported for pyridoxal phosphate modified Hb (54). Although, such interactions are likely to exist in carboxymethylated Hb and galacturonic acid modified Hb (27), phosphate mediated interactions in HPPr-HbA and α2(βPLP)2 seem to be more intense. These interactions that operate across the ββ-cleft stabilizing a deoxy-like state conformation are considered to serve as the ‘pseudo crosslinks’ within the DPG pocket (55-56).

HPPr-HbA reacts with DBBF under deoxy conditions in much the same way as the unmodified HbA in terms of the reactivity of Lys-99(α) to form cross-bridge. Thus, the electrostatic modification of Val-1(β) of ββ-cleft does not seem to perturb the orientation or reactivity of the ε-amino groups of Lys-99(α) in the deoxy state. Besides, αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA exhibited an isoelectric point comparable to that of HPPr-HbA. The loss of positive charge resulting from the αα-fumaryl-crosslinking is not apparent from the isoelectric focusing pattern. This behavior is consistent with the earlier observation that the isoelectric focusing pattern of αα-fumaryl-HbA under oxy conditions is nearly identical to the isoelectric focusing pattern of HbA (5). This compensation in the charge of HbA has been suggested to be a result of an increased pKa of a neighboring residue, Glu-101(α). This phenomenon seems to be conserved in the doubly modified derivative, αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. This behavior is distinct as compared to that seen on the generation of αα-fumaryl-Hb-P (31). The electrostatic modifications in αα-fumaryl-Hb-P are both from the mid central cavity whereas αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA has one modification in the mid central cavity and the other in the ββ-cleft.

Combining the electrostatic modification of Val-1(β) with αα-fumaryl crosslinking results in a partial additive influence in terms of reducing the O2-affinity of HbA. From the mutant hemoglobin analysis, it has been hypothesized that the number of positive charges in the central cavity determines the O2-affinity of the molecule (58). It is suggested that the stability of the T-structure is inversely proportional to the overall positive charge in the central cavity. Accordingly, lowered O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA is consistent with the hypothesis that the reduction of the positive charge in the central cavity of Hb generates a more stable T-structure.

αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA lacks sensitivity towards the allosteric effectors, chloride, DPG and IHP. The molecular modeling studies of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA indicated that the fumaryl crosslink can be introduced into the mid central cavity of HPPr-HbA with out altering the positions of the HPPr groups at Val-1(β) (Fig 6). Therefore, the electrostatic interactions between phosphates of the HPPr group and positive charges of DPG residues that are possible in HPPr-HbA can also operate in αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA. The presence of αα-fumaryl crossbridge in the mid central cavity coupled with the ‘pseudo crosslink’ in the ββ-cleft can therefore be expected to drastically reduce the plasticity of the molecule in these two domains of the central cavity. It may be noted that HbA carboxymethylated at all its four α-amino groups is also insensitive to the presence of these effectors (4). Thus desensitization of Hb to the presence of chloride, DPG and IHP can be achieved by either electrostatic modification of the αα-end and the ββ-cleft of the central cavity, or by combining the electrostatic modification of the ββ-cleft with the αα-fumaryl crosslinking in the mid central cavity of HbA.

αα-fumaryl-HbA exhibited reduced sensitivity to L35 as compared to HbA. This is expected as L35 binds at the αα-end with its distal end projecting into the cavity closer to Lys-99 of α-chain (38). Similarly, αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA also exhibited reduced sensitivity to L35. However, although the extent of modulation of the O2-affinity of αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA by L35 was less than that of HbA, the O2-affinity of this derivative in the presence of L35 was lower than that of HbA and was comparable to that of HPPr-HbA in the presence of the same effector. The electrostatic modification of the ββ-cleft of αα-fumaryl-HbA compensates for the structural consequences of the presence of the cross-bridge in the mid-central cavity that reduces the modulation of the O2-affinity of HbA by L35.

Geminate recombination of CO is highly responsive to the conformational properties of HbA (39-44). The geminate binding of CO to photodissociated COHb occurs within a few hundred nanoseconds. Therefore, the geminate yield indicates the ligand binding affinity of the foremost structure of Hb in R to T transition. Apparently, this initial structure is expected to have the highest geminate yield since other structures in R to T transition attain lower ligand affinity conformation. The present geminate binding studies of modified Hbs indicated that HPPr modification reduces the ligand binding affinity of the initial population of photodissociated HbA more than αα-fumaryl-crosslinking. However, the P50 values of HPPr-HbA and αα-fumaryl-HbA were comparable. This may implicate that the subsequent structures in R to T transition of αα-fumaryl-HbA exhibit a larger variation in ligand binding affinity as compared to those of HPPr-HbA. In αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA, both modifications exerted combined influence on geminate binding as well as on overall O2-affinity. The influence of IHP was less on geminate yield and more on P50 of αα-fumaryl-HbA as compared to that of HbA. Low ligand affinity structures of αα-fumaryl-HbA seem to respond more to IHP than the initial population. Similarly, the effect of L35 was less on geminate yield of HPPr-HbA and more on its P50 than of HbA, indicating the enhanced influence of L35 on intermediate structures of HPPr-HbA in R to T transition.

The frequency of ν(Fe-His) indicates the conformation of Hb at the heme surroundings (39-46). This frequency is highest for fully liganded R structure and lowest for unliganded T structure. Modified hemoglobins with low O2-affinity have been shown to have reduced ν(Fe-His) frequency in the liganded state. Since the frequency of ν(Fe-His) reflects the structure of liganded R state and geminate yield determines the structure of the initial population for recombination, the comparison of these two parameters of modified Hb may indicate the ease with which one molecule undergoes changes in the tertiary structure at the heme after photodissociation. αα-fumaryl-HbA and HPPr-HbA exhibited reduced frequency than HbA, indicating conformational changes at the heme. Interestingly, αα-crosslinking reduced the frequency more than HPPr modification, whereas the later modification reduced the geminate binding more than the former. This may be interpreted that HPPr modification did not alter the R state structure of HbA in the heme environment as much as αα-crosslinking. However, HPPr-HbA undergoes structural changes at the heme more rapidly than αα-fumaryl-HbA, upon photodissociation.

The change in the reactivity of Cys-93(α) in oxy state can be considered as an indicator of a change at the α1β2 interface in a given mutant or chemically modified Hb (48-53). The electrostatic modification at the ββ-cleft had no influence on the reactivity of Cys-93(β), even though its O2-affinity was lower than that of HbA. On the other hand, the αα-fumaryl crossbridge that lowers the O2-affinity of HbA also lowered the reactivity of Cys-93(β). The doubly modified Hb, αα-fumaryl-HPPr-HbA, exhibited a Cys-93(β) reactivity even lower than that of αα-fumaryl-HbA, a synergistic influence of the two modifications.

The fumarate mediated cross-linking of Lys-99(α) of hemoglobin reduces the O2-affinity of the tetramer without apparent alterations in its deoxy conformation (5). The reduction in O2-affinity is primarily due to the reduction in KR (59). Accordingly, the R-structure of αα-fumaryl-HbA has been predicted to be different as compared to that of HbA. The environment of Cys-93(β) of αα-fumaryl-HbA appears to be perturbed from the one in the R-structure of HbA, reducing the reactivity of its thiol group. The reduced reactivity of Cys-93(β) on deoxygenation of HbA has been attributed to the conformational changes as well as to the salt bridge formed between His-146(β) and Asp-94(β) (49). Des-His-146(β) HbA exhibited an increased reactivity of Cys-93(β) in oxy conformation, indicating that His-146(β) influences the reactivity of Cys-93(β) even in oxy structure. The FT-IR studies of oxy and met hemoglobins suggested a correlation between the reactivity of Cys-93(β) and the probability of this residue being external to the F-H pocket (60). An interaction between Cys-93(β) and Tyr-145(β) that can influence the reactivity of Cys-93(β) has also been suggested. The αα-fumaryl cross-linking of HbA has altered one or more of these interactions resulting in a reduction in the reactivity of Cys-93(β) in the oxy conformation.

The results of the present study along with the earlier results of αα-fumaryl-Hb-P, and the tetra carboxymethylated Hb demonstrated that electrostatic modification of the ββ-end, αα-end and mid central cavity that lower the O2-affinity can be combined in pairs to generate species of Hb that exhibit O2-affinity lower than that with either of the modifications. An interesting aspect of the two very low O2-affinity forms of Hb generated by combining the two chemical perturbations of central cavity of Hb, namely αα-fumaryl-Hb-P and αα-fumaryl-HPPr-Hb is that the O2-affinity of both species are insensitive to the presence of allosteric effecors. Presumably, these represent the conformational state of Hb wherein the protein has accessed the very low affinity T-state. In contrast, PEGylation of Hb particularly hexaPEGylation of Hb with PEG-5000 induces a degree of rigidity to the oxy conformational state of Hb which is apparently a high O2-affinity R-state, again non responsive to allosteric effectors. If the very low O2-affinity Hbs are subjected to hexaPEGylation protocol that we have used to generate the current versions of non-hypertensive Hbs, it is conceivable that PEGylated Hbs with very low oxygen affinity are generated.

HexaPEGylation of αα-fumaryl cross-linked Hb generated a product that has an O2-affinity comparable to that of unmodified Hb (26). The presence of αα-fumaryl cross-link in the PEGylated-Hb has compensated partially the high oxygen affinity inducing propensity of PEGylation reaction. The oxygen affinity of the PEGylated αα-fumaryl Hb is intermediate to that of PEGylated Hb and αα-fumaryl Hb. The G3P modification in HPPr-αα-fumaryl-HbA is expected to further neutralize the influence of PEGylation to generate a PEGylated Hb with an oxygen affinity intermediate to that of PEGylated αα-fumaryl Hb and HPPr-αα-fumaryl-HbA. Availability of a series of PEGylated Hbs with varying oxygen affinities can facilitate the production of non-hypertensive PEGylated Hbs as blood substitutes for customized clinical applications.

Abbreviations

- ACN

acetonitrile

- DBBF

bis dibromosalicyl fumarate

- DPG

2,3-diphosphoglycerate

- GY

geminate yield

- Hb-P

Hb-Presbyterian

- HFBA

heptafluorobutyric acid

- HPPr

2-hydroxy 3-phospho propyl

- IEF

Isoelectric focusing

- IHP

inositol hexaphosphate

- L35

2-[4-(3,5-dichlorophenylureido)phenoxy]-2-methylpropionic acid

- 4-PDS

4,4’-dithiodipyridine

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- RPHPLC

reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid (9951021T) from the American Heart Association Heritage Affiliate and grants from the National Institute of Health (HL58247 and HL71064) and the US Army (PR023085).

REFERENCES

- 1.Walder JA, Walder RY, Arnone A. Development of antisickling compounds that chemically modify hemoglobin S specifically within the 2,3-diphosphoglycerate binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 1980;141:195–216. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benesch R, Benesch RE. Preparation and properties of hemoglobin modified with derivatives of pyridoxal. Methods Enzymol. 1981;76:147–159. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)76123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee R, Walder RY, Arnone A, Walder JA. Mechanism for the increase in solubility of deoxyhemoglobin S due to cross-linking the beta chains between lysine-82 beta 1 and lysine-82 beta 2. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5901–5909. doi: 10.1021/bi00266a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiDonato A, Fantl WJ, Acharya AS, Manning JM. Selective carboxymethylation of the alpha-amino groups of hemoglobin. Effect on functional properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:11890–11895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee R, Welty EV, Walder RY, Pruitt SL, Rogers PH, Arnone A, Walder JA. Isolation and characterization of a new hemoglobin derivative cross-linked between the alpha chains (lysine 99 alpha 1----lysine 99 alpha 2) J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:9929–9937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fantl WJ, Manning LR, Ueno H, Di Donato A, Manning JM. Properties of carboxymethylated cross-linked hemoglobin A. Biochemistry. 1987;26:5755–5761. doi: 10.1021/bi00392a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hess JR, Macdonald VW, Brinkley WW. Systemic and pulmonary hypertension after resuscitation with cell-free hemoglobin. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;74:1769–1778. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saxena R, Wijnhoud AD, Carton H. Controlled safety study of a hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier, DCLHb, in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:993–996. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberthal W, Fuhro R, Alam H, Rhee P, Szebeni J, Hechtman HB, Favuzza J, Veech RL, Valeri CR. Comparison of the effects of a 50% exchange-transfusion with albumin, hetastarch, and modified hemoglobin solutions. Shock. 2002;17:61–69. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200201000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim HW, Greenburg AG. Ferrrous hemoglobin scavenging of endothelium derived nitric oxide is a principal mechanism for hemoglobin mediated vasoactivities in isolated rat thoracic aorta. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 1997;25:121–133. doi: 10.3109/10731199709118904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doherty DH, Doyle MP, Curry SR, Vali RJ, Fattor TJ, Olson JS, Lemon DD. Rate of reaction with nitric oxide determines the hypertensive effect of cell-free hemoglobin. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:672–676. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HW, Greenburg AG. Mechanisms for vasoconstriction and decreased blood flow following intravenous administration of cell-free native hemoglobin solutions. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2005;566:397–401. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26206-7_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eich RF, Li T, Lemon DD, Doherty DH, Curry SR, Aitken JF, Mathews AJ, Johnson KA, Smith RD, Phillips GN, Jr., Olson JS, Lemon DD. Mechanism of NO-induced oxidation of myoglobin and hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6976–6983. doi: 10.1021/bi960442g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson JS, Eich RF, Smith LP, Warren JJ, Knowles BC. Protein engineering strategies for designing more stable hemoglobin-based blood substitutes. Artif Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 1997;25:227–241. doi: 10.3109/10731199709118912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dou Y, Maillett DH, Eich RF, Olson JS. Myoglobin as a model system for designing heme protein based blood substitutes. Biophys. Chem. 2002;98:127–148. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conover CD, Malatesta P, Lejeune L, Chang CL, Shorr RG. The effects of hemodilution with polyethylene glycol bovine hemoglobin (PEG-Hb) in a conscious porcine model. J. Investig. Med. 1996;44:238–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conover CD, Lejeune L, Shum K, Gilbert C, Shorr RG. Physiological effect of polyethylene glycol conjugation on stroma-free bovine hemoglobin in the conscious dog after partial exchange transfusion. Artif. Organs. 1997;21:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1997.tb00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandegriff KD, Malavalli A, Wooldridge J, Lohman J, Winslow RM. MP4, a new nonvasoactive PEG-Hb conjugate. Transfusion. 2003;43:509–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acharya SA, Friedman JM, Manjula BN, Intaglietta M, Tsai AG, Winslow RM, Malavalli A, Vandegriff K, Smith PK. Enhanced molecular volume of conservatively pegylated Hb: (SP-PEG5K)6-HbA is non-hypertensive. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 2005;33:239–255. doi: 10.1081/bio-200066365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manjula BN, Tsai AG, Intaglietta M, Tsai CH, Ho C, Smith PK, Perumalsamy K, Kanika ND, Friedman JM, Acharya SA. Conjugation of multiple copies of polyethylene glycol to hemoglobin facilitated through thiolation: influence on hemoglobin structure and function. Protein J. 2005;24:133–146. doi: 10.1007/s10930-005-7837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu T, Prabhakaran M, Acharya SA, Manjula BN. Influence of the chemistry of conjugation of poly(ethylene glycol) to Hb on the oxygen-binding and solution properties of the PEG-Hb conjugate. Biochem. J. 2005;392:555–564. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acharya SA, Smith PK, Manjula BN. Pegylated non-hypertensive hemoglobins, methods of preparing same, and uses thereof. US patent US2005159339. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winslow RM, Gonzales A, Gonzales ML, Magde M, McCarthy M, Rohlfs RJ, Vandegriff KD. Vascular resistance and the efficacy of red cell substitutes in a rat hemorrhage model. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998;85:993–1003. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai AG, Vandegriff KD, Intaglietta M, Winslow RM. Targeted O2 delivery by low-P50 hemoglobin: a new basis for O2 therapeutics. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:1411–1419. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00307.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai AG, Cabrales P, Intaglietta M. Oxygen-carrying blood substitutes: a microvascular perspective. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2004;4:1147–1157. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.7.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu T, Manjula BN, Li D, Brenowitz M, Acharya SA. Influence of intramolecular cross-links on the molecular, structural and functional properties of PEGylated hemoglobin. Biochem. J. 2007;402:143–151. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya AS, Bobelis DJ, White SP. Electrostatic modification at the amino termini of hemoglobin A. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:2796–2804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benesch RE, Yung S, Suzuki T, Bauer C, Benesch R. Pyridoxal compounds as specific reagents for the alpha and beta N-termini of hemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:2595–2599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.9.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez EJ, Abad-Zapatero C, Olsen KW. Crystal structure of Lysbeta(1)82-Lysbeta(2)82 crosslinked hemoglobin: a possible allosteric intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;296:1245–1256. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwiatkowski LD, Hui HL, Wierzba A, Noble RW, Walder RY, Peterson ES, Sligar SG, Sanders KE. Preparation and kinetic characterization of a series of betaW37 variants of human hemoglobin A: evidence for high-affinity T quaternary structures. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4325–4335. doi: 10.1021/bi970866q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manjula BN, Malavalli A, Prabhakaran M, Friedman JM, Acharya AS. Activation of the low oxygen affinity-inducing potential of the Asn108(beta)-->Lys mutation of Hb-Presbyterian on intramolecular alpha alpha-fumaryl cross-bridging. Protein Eng. 2001;14:359–366. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.5.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy RP, Acharya AS. Semisynthesis of hemoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1994;231:194–215. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)31014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu Z, Friso G, Miranda JJ, Patel MJ, Lo-Tseng T, Moore EG, Burlingame AL. Structural characterization of human hemoglobin crosslinked by bis(3,5-dibromosalicyl) fumarate using mass spectrometric techniques. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2568–2577. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ampulski RS, Ayers VE, Morell SA. Determination of the reactive sulfhydryl groups in heme proteins with 4,4'-dipyridinedisulfide. Anal. Biochem. 1969;32:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan I, Dantsker D, Samuni U, Friedman AJ, Bonaventura C, Manjula B, Acharya SA, Friedman JM. Beta 93 modified hemoglobin: kinetic and conformational consequences. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7581–7592. doi: 10.1021/bi010051o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fermi G, Perutz MF, Shaanan B, Fourme R. The crystal structure of human deoxyhaemoglobin at 1.74 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;175:159–174. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richard V, Dodson GG, Mauguen Y. Human deoxyhaemoglobin-2,3-diphosphoglycerate complex low-salt structure at 2.5 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;233:270–274. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lalezari I, Lalezari P, Poyart C, Marden M, Kister J, Bohn B, Fermi G, Perutz MF. New effectors of human hemoglobin: structure and function. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1515–1523. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman JM. Structure, dynamics, and reactivity in hemoglobin. Science. 1985;228:1273–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.4001941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedman JM, Scott TW, Fisanick GJ, Simon SR, Findsen EW, Ondrias MR, MacDonald VW. Localized control of ligand binding in hemoglobin: effect of tertiary structure on picosecond geminate recombination. Science. 1985;229:187–190. doi: 10.1126/science.4012316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marden MC, Hazard ES, Kimble C, Gibson QH. Geminate ligand recombination as a probe of the R, T equilibrium in hemoglobin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987;169:611–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray LP, Hofrichter J, Henry ER, Ikeda-Saito M, Kitagishi K, Yonetani T, Eaton WA. The effect of quaternary structure on the kinetics of conformational changes and nanosecond geminate rebinding of carbon monoxide to hemoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:2151–2155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedman JM. Time-resolved resonance Raman spectroscopy as probe of structure, dynamics, and reactivity in hemoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1994;232:205–231. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)32049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J, Juszczak LJ, Peterson ES, Shannon C, Yang M, Huang S, Vidugiris GV, Friedman JM. The conformational and dynamic basis for ligand binding reactivity in hemoglobin Ypsilanti (beta 99 asp-->Tyr): origin of the quaternary enhancement effect. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4514–4525. doi: 10.1021/bi982724h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedman JM, Scott TW, Stepnoski RA, Ikeda-Saito M, Yonetani T. The iron-proximal histidine linkage and protein control of oxygen binding in hemoglobin. A transient Raman study. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:10564–10572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson ES, Friedman JM. A possible allosteric communication pathway identified through a resonance Raman study of four beta37 mutants of human hemoglobin A. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4346–4357. doi: 10.1021/bi9708693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathews AJ, Rohlfs RJ, Olson JS, Tame J, Renaud JP, Nagai K. The effects of E7 and E11 mutations on the kinetics of ligand binding to R state human hemoglobin. J. Biol Chem. 1989;264:16573–16583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imai K, Hamilton HB, Miyaji T, Shibata S. Physicochemical studies of the relation between structure and function in hemoglobin Hiroshima (HC3 , histidine leads to aspartate) Biochemistry. 1972;11:114–121. doi: 10.1021/bi00751a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kilmartin JV, Hewitt JA, Wootton JF. Alteration of functional properties associated with the change in quaternary structure in unliganded haemoglobin. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;93:203–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taketa F, Antholine WE, Mauk AG, Libnoch JA. Nitrosylhemoglobin Wood: effects of inositol hexaphosphate on thiol reactivity and electron paramagnetic resonance spectrum. Biochemistry. 1975;14:3229–3233. doi: 10.1021/bi00685a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imai K, Tsuneshige A, Harano T, Harano K. Structure-function relationships in hemoglobin Kariya, Lys-40(C5) alpha----Glu, with high oxygen affinity. Functional role of the salt bridge between Lys-40 alpha and the beta chain COOH terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:11174–11180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonaventura C, Tesh S, Faulkner KM, Kraiter D, Crumbliss AL. Conformational fluctuations in deoxy hemoglobin revealed as a major contributor to anionic modulation of function through studies of the oxygenation and oxidation of hemoglobins A0 and Deer Lodge beta2(NA2)His --> Arg. Biochemistry. 1998;37:496–506. doi: 10.1021/bi971574s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mawjood AH, Miyazaki G, Kaneko R, Wada Y, Imai K. Site-directed mutagenesis in hemoglobin: test of functional homology of the F9 amino acid residues of hemoglobin alpha and beta chains. Protein Eng. 2000;13:113–120. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haney DN, Bunn HF. Glycosylation of hemoglobin in vitro: affinity labeling of hemoglobin by glucose-6-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3534–3538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arnone A, Benesch RE, Benesch R. Structure of human deoxyhemoglobin specifically modified with pyridoxal compounds. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;115:627–642. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fronticelli C, Bucci E, Razynska A, Sznajder J, Urbaitis B, Gryczynski Z. Bovine hemoglobin pseudo-crosslinked with mono(3,5-dibromosalicyl)-fumarate. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;193:331–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Razynska A, Matheson-Urbaitis B, Fronticelli C, Collins JH, Bucci E. Stabilization of the tetrameric structure of human and bovine hemoglobins by pseudocrosslinking with muconic acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;326:119–125. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perutz MF, Shih D. T-b., Williamson D. The chloride effect in human haemoglobin. A new kind of allosteric mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;239:555–560. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vandegriff KD, Medina F, Marini MA, Winslow RM. Equilibrium oxygen binding to human hemoglobin cross-linked between the alpha chains by bis(3,5-dibromosalicyl) fumarate. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:17824–17833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moh PP, Fiamingo FG, Alben JO. Conformational sensitivity of beta-93 cysteine SH to ligation of hemoglobin observed by FT-IR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1987;26:6243–6249. doi: 10.1021/bi00393a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]