Abstract

The conductive polymer polypyrrole was blended with alginate to investigate its potential in tissue engineering applications. This study showed that increasing the polypyrrole content altered the macroscopic structural morphology of the polymer blend scaffold, but did not alter the overall conductivity of the polymer blend, which was 10−2 S/cm2. Culturing of human umbilical vein endothelial cells on the polymer blend scaffolds showed that addition of polypyrrole mediated cell attachment to the polymer scaffold. However, cell proliferation was dependent on the polypyrrole content, with 0.025% v/v polypyrrole giving the best results. Using an ischemia-reperfusion rat myocardial infarction model, local injection of 0.025% polypyrrole in alginate polymer blend into the infarct zone yielded significantly higher levels of arteriogenesis at 5 weeks post-treatment when compared with the saline control group and the alginate only treatment group. In addition, this alginate-polypyrrole polymer blend significantly enhanced infiltration of myofibroblasts into the infarct area when compared with the control group. The results of this study highlight the potential clinical benefit of using this alginate-polypyrrole polymer blend as an injectable scaffold to repair ischemic myocardium after myocardial infarction.

Keywords: alginate, cardiac tissue engineering, polymer blend, polypyrrole

Introduction

In spite of advances in the treatment of myocardial infarction (MI), the loss of nonregenerative cardiomyocytes, negative remodeling of the left ventricle (LV), and the deterioration of myocardial function continue to be a major cause of congestive heart failure[1, 2]. Matrix biopolymers (e.g. fibrin glue, collagen) have shown much promise in the treatment of MI, by showing marked improvement in remodeling by providing a structural support to the aneurismal thinning of the LV wall[3–6].

In addition, there has been a growing interest of late in utilizing conducting polymers for tissue engineering applications. Conducting polymers offer certain advantages over non-conductive biopolymers in that their physical characteristics and conductive properties can be manipulated either chemically or electrochemically. Our lab’s interest in conducting polymers stems from the assumption that many (cardiac) cell functions—cell attachment, proliferation, and migration—may be modulated by electrical stimulation[7]. The most widely studied conducting polymer has been polypyrrole (PPy), which has been investigated for its potential as bio-probes[8, 9], in stimulating nerve regeneration[10, 11], and as artificial muscles[12].

PPy is a polycationic electrically conductive polymer that can be easily synthesized electrochemically or chemically into thin films, thick films, or colloidal microparticles. Previous studies have shown that various cell types, e.g. neurons[10, 11] and endothelial cells[13], can proliferate and differentiate on PPy films in vitro. In vivo studies have shown that PPy are not cytotoxic[14] in various animals—e.g. rats, rabbits, guinea pigs—and has shown promising results in regenerating damaged nerve tissue[11].

However, PPy, particularly as thin films, can be at times quite brittle and difficult to mechanically manipulate and process. To overcome this limitation, other labs have looked into blending PPy with other more pliable materials[15–17]. One such material can be the biopolymer alginate. Alginate is a naturally occurring biopolymer isolated from seaweed and has been used as a synthetic extracellular matrix in cell encapsulation[18, 19], cell transplantation[20], and tissue engineering[21]. Alginate is composed of blocks of (1–4) beta-D-mannuronic acid monomers (M) and blocks of alpha-L-guluronic acid monomers (G). The amount of each monomer and the sequential distribution of the monomer blocks along a polymer chain vary depending on the source of the alginate. Divalent cations such as Ca2+ bind blocks of G monomers along adjacent polymer chains, creating ionic interchain salt bridges which result in gelation of the aqueous alginate solutions[22, 23].

An added advantage to using alginate is that it is an injectable biopolymer. Injectable biopolymers provide a less invasive and potentially more effective tissue-engineering approach for myocardial reconstruction when compared to external scaffold patches, which require surgically invasive procedures to incorporate them onto the epicardial surface. Furthermore, injectable biopolymers are able to deform with the dynamically loaded myocardial environment and to align their matrix with the injured region[6].

Here, we show that by blending PPy with alginate we can enhance cell attachment and proliferation on the polymer blend scaffold. Furthermore, injection of the LVM-PPy polymer blend into infarcted rat hearts resulted in enhanced arteriogenesis, i.e. increased arteriole density within the infarct scar, compared to the control group, as well as the LVM only treatment group.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Polypyrrole (5% w/v solution) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LVM-Alginate was obtained from Novamatrix (Sandvika, Norway). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and cell culture media and supplements were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland); disposable tissue culture supplies were purchased from Fisher (Pittsburg, PA). Sterile 0.9% saline solution was purchased from Cardinal Health (Dublin, OH).

2.2 Analyzing the LVM-PPy scaffolds

A 2% w/v LVM-alginate solution was prepared in 0.9% saline solution. To that mixture various amounts of the polypyrrole (PPy) solution was added. The alginate containing PPy (LVM-PPy) solutions were then vortexed and sonicated for several hours to assure that we obtained a homogeneous mixture. Morphological assessment of the various polymer blends were done by first mixing equivolumes of the polymer solution with 102 mM CaCl2. Once gelation had occurred the hydrogels were then flash frozen in O.C.T. freezing medium (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and later sectioned into 10 µm slices. The sections were observed under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E800) under 10X and 20X magnifications.

Conductivity of the polymer blends was determined using a four-point probe. Discs of the polymer blends were either incubated in the cell media for 1 day or for 7 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. The media was changed every 2–3 days.

2.3 Cell viability and proliferation

In 6-well plates, the bottom of each well was coated with the polymer solution. The hydrogels were formed by addition of an equivolume of 102 mM CaCl2 solution. Afterwards, HUVECs along with cell media were added on top of the polymer scaffolds. The cells were then allowed to grow for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. Cell viability was determined with a LIVE/DEAD assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cells were visualized with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE300). Cell proliferation was assessed using a MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) tetrazolium/formazan assay (Promega, Madison, WI)[24, 25]. The absorbance measurements (at 490 nm) were then normalized to the absorbance measurements on day 7 for cells grown in the absence of a polymer scaffold, i.e. only on tissue-culture treated plates.

2.4 Acute myocardial infarction model

All surgical procedures were approved by the Committee for Animal Research of the University of California San Francisco (San Francisco, CA). The ischemia–reperfusion model used in this study has been extensively tested in our lab[3, 4, 26]. Female Sprague-Dawley rats (225–250 g) were anesthetized with ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The chest was opened by a median sternotomy, and a single stitch of 7-0 Ticron suture (United States Surgical division of Tyco Healthcare, Norwalk, CT) was introduced around the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery and tightened to occlude for 25 min before reperfusing the vessel. The chest was then closed and the animal was allowed to recover for 1 week. This acute infarct model has previously been shown to create infarct sizes of approximately 30% of the LV with reperfusion[27–29].

2.5 Biopolymer injection

One week after myocardial infarction, rats were randomized into alginate only (LVM only), LVM-PPy (0.025% PPy in 2% LVM), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) control groups (n = 6/group). The animals were anesthetized and the abdomen was opened. The LV apex was exposed via a subdiaphragmatic incision, leaving the chest wall and sternum intact. For each treatment group, a total volume of 100 µL was injected into the infarcted LV region of each heart, using a 1 mL duploject syringe system and a 27- gauge needle. The diaphragm was sutured closed after suction of the chest cavity and the abdomen was subsequently closed. Five weeks after injections, the rats were euthanized with a sodium pentobarbital overdose (200 mg/kg).

2.6 Histology, immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence

Immediately after the animals were sacrificed, the hearts were excised and fresh-frozen in O.C.T. freezing medium, and later sectioned into 10-µm slices. Representative slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome stain. Morphometric analysis of infarct size were quantified according to published methods[30].

Inflammation was assessed by immunohistochemical staining with mouse monoclonal anti-macrophage/monocyte (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). The staining assay was performed with a Mouse on Rat HRP-Polymer Kit (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) and with an animal research kit (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA).

Arteriogenesis in the infarct was examined by immunofluorescence staining with mouse monoclonal anti-α-smooth muscle actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to detect arterioles and myofibroblasts.[31] Arterioles were visualized via fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. Arterioles in the infarct were identified as staining positive for α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and as having a visible lumen with a diameter between 10 and 100 µm.[3, 32] Arteriole density was calculated as the average number of arterioles in the total infarct area, out of five representative slides per sample. As a negative control, we omitted the primary antibody.

2.7 Statistics

All data are expressed as mean +/− standard deviation. Student’s t-test and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for parameter estimation and hypothesis testing, with p < 0.05 being considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

This study involved 18 animals, each group consisting of 6 animals for the 1 week post-injection studies. 5 rats died either immediately after the myocardial infarct (MI) or just prior to the injections, while 2 rats died immediately during the polymer injections (presumably due to injections into the LV lumen instead of the LV wall). After successful surgical injections, however, there was 100% survival in all groups.

3.1 Polymer blend morphology and conductivity

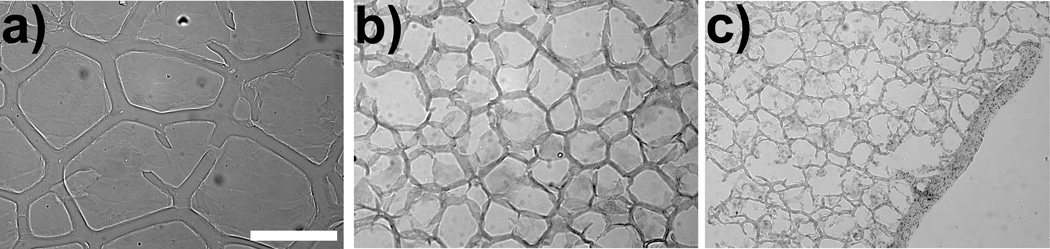

A qualitative assessment of the macroscopic structural morphology of the alginate-polypyrrole polymer blend hydrogels were undertaken by freezing the hydrogels in OCT and then sectioning them into 10 µm slices. The slices were then observed under light microscopy. As seen in Fig. 1, addition of PPy to the alginate appears to alter the biopolymer’s macroscopic structural morphology. Polymer hydrogels containing higher concentrations of PPy seemed to exhibit less elasticity and reduced mechanical integrity, becoming more brittle and falling apart more easily than their LVM only counterparts. Alginate-polypyrrole polymer blends containing beyond 0.2% v/v PPy were too difficult to handle and maintain, and, thus, we were unable to obtain consistent and reliable in vitro results with polymer blends containing higher concentrations of PPy.

Figure 1.

Alginate scaffolds containing 0% (a), 0.05% (b), and 0.2 % (c) PPy. Magnification is at 10×. The bar represents 250 µm.

Since changes in conductivity may affect cell proliferation and viability, conductivity measurements of the various polymer blends were performed with a four-point probe. Discs of the polymer blends were made trying to make them as thin as possible. The bulk conductivity of the different polymer blends, which ranged from 0.025% v/v PPy to 0.2% v/v PPy, were found to be all around 10−2 S/cm2. There were no apparent differences in the conductivity of polymer blends that have been incubated in the cell media for 1 day versus 7 days.

3.2 In vitro cell viability, attachment, and proliferation

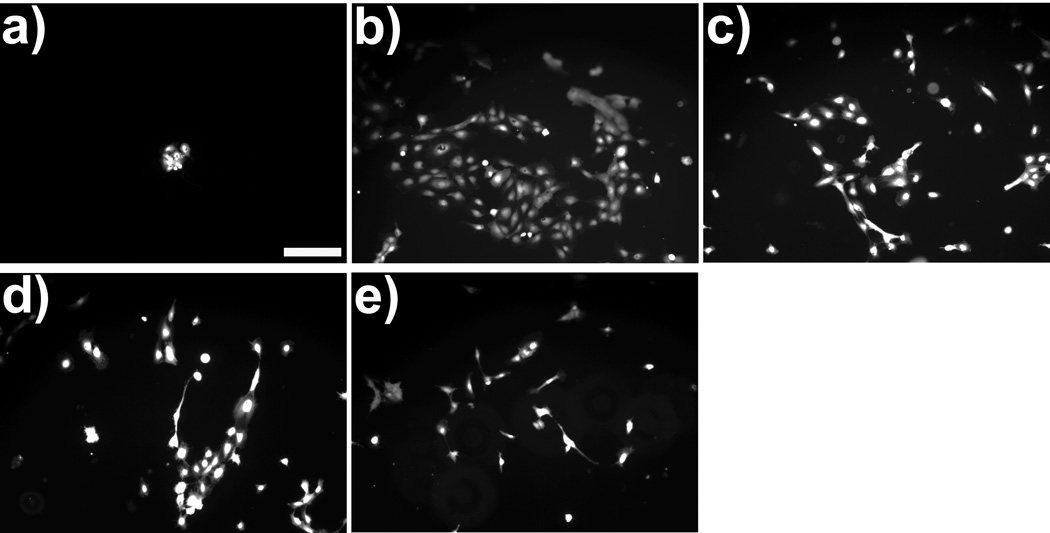

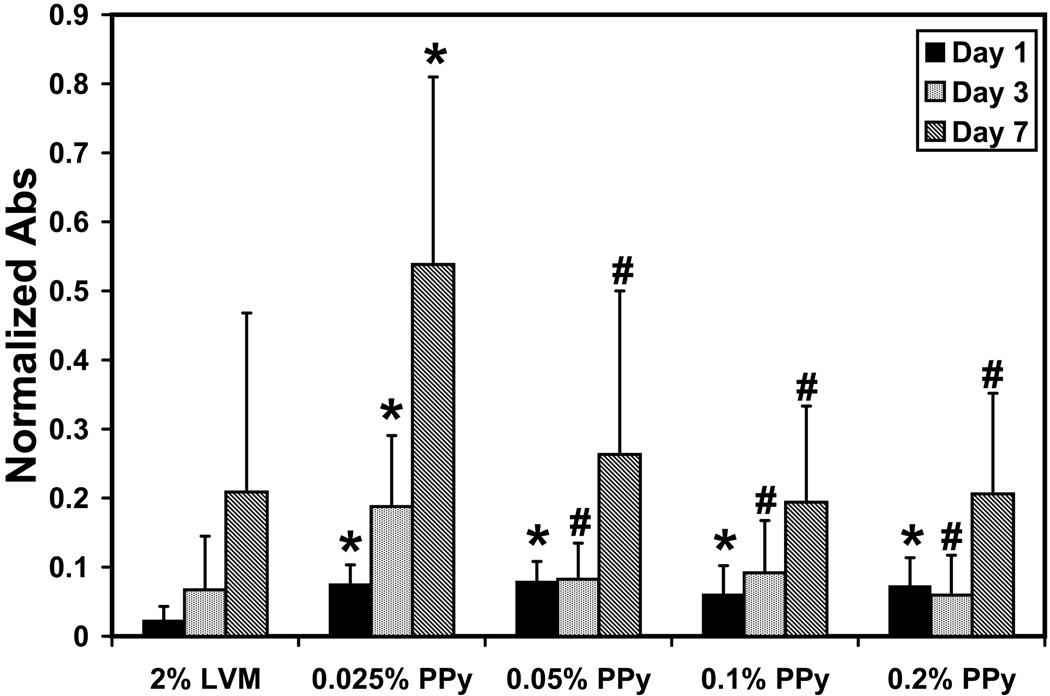

To assess the ability of the alginate-polypyrrole polymer blends to promote cell survival, attachment, and proliferation, on a two dimensional in vitro model, HUVECs were cultured on the various LVM-PPy polymer blends for up to 7 days. Morphologically, the cells were spread out, indicating adherence to the polymer scaffold (Fig. 2). Use of the LIVE/DEAD assay confirmed that all the adherent cells were viable. Hence, the alginate-polypyrrole polymer blends appeared to have no cytotoxic effect. Furthermore, it would seem that the inclusion of PPy mediated or enhanced cell attachment to the polymer scaffold; this is particularly evident on day 1. Proliferation studies (Fig. 3) confirmed this observation, showing that the alginate-polypyrrole polymer blends exhibited statistically higher cell populations for day 1 relative to the LVM only scaffolds. However, only the combination of 0.025% v/v PPy in 2% LVM provided statistically better cell growth when compared to the LVM only scaffold, as well as the other LVM-PPy blends, after day 1.

Figure 2.

Morphology of HUVECs after 1 day incubation on: (a) LVM only; (b) 0.025% PPy; (c) 0.05% PPy; (d) 0.1% PPy; and (e) 0.2% PPy. The cells were stained with a LIVE/DEAD assay. The observed fluorescence due to the presence of calcein in the cells indicated that these adherent cells were viable. Magnification is at 10×. The bar represents 200 µm.

Figure 3.

Proliferation assay of HUVECs. The absorbance (at λ=490 nm) measurements have been normalized to those of day 7 for cells grown in the absence of any polymer scaffold. Statistically significant differences are indicated by (*) when compared to LVM only and by (#) when compared to 0.025% PPy in 2% LVM.

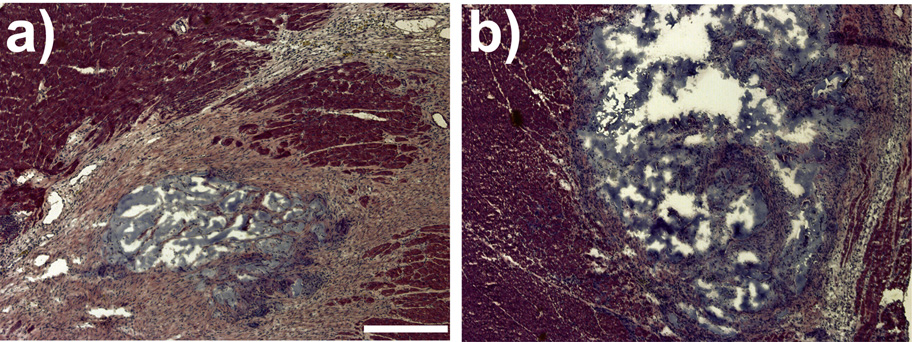

3.3 Histological assessment

H&E stained sections (Fig. 4) of the hearts 5 weeks post-injections revealed a continued presence of the polymers within the infarct area. Masson’s trichrome staining confirmed that the infarct scar was highly populated by dense collagen. The infarct size was determined from both H&E stained slides and Masson’s trichrome stained slides. The mean infarct size was not significantly different between the LVM only and the LVM-PPy (0.025% PPy in 2% LVM) treatment groups.

Figure 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin stains of heart sections from rats treated with LVM only (a) or LVM-PPy (b). Magnification is at 4X. The bar represents 400 µm.

To determine inflammation we stained representative slides for the presence of monocytes and macrophages. There was no significant inflammation associated with the LVM only or the LVM-PPy treatment groups. There was no obvious difference between the biopolymer treatment groups and the PBS control groups.

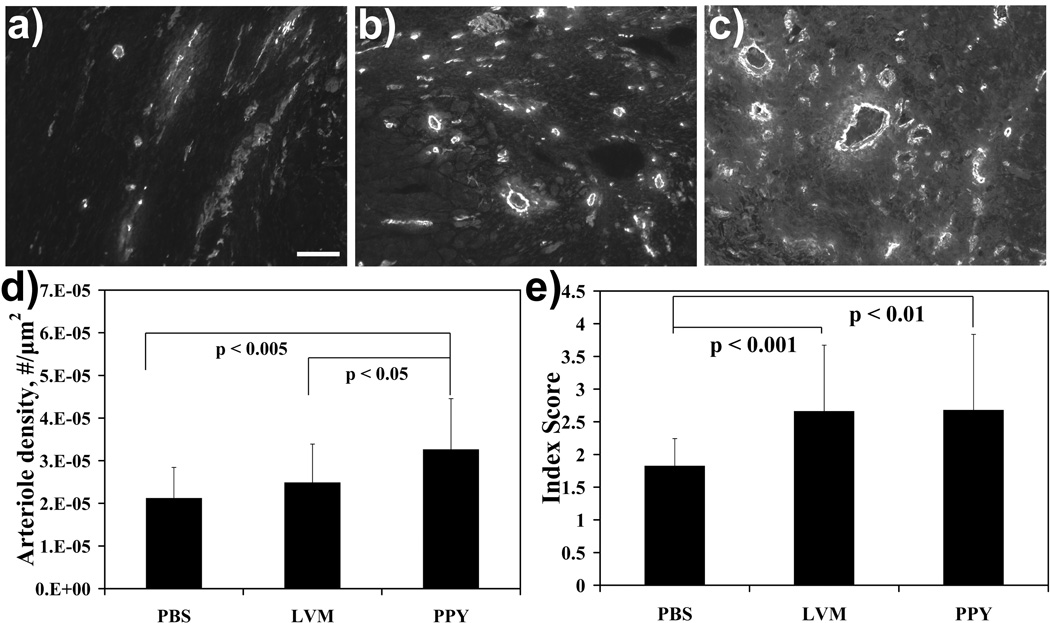

3.4 In vivo Arteriogenesis

Arteriole density, one indicator of angiogenesis, was assessed (Fig. 5). In this case, the mean arteriole density in the PBS control group was 21 +/− 7 arterioles/mm2, which was significantly lower (p < 0.005) from that of the LVM-PPy treatment group (33 +/− 12 arterioles/mm2). The LVM only treatment group (25 +/− 9 arterioles/mm2) showed a trend toward higher arteriole density. In addition, the arteriole density for the LVM-PPy treatment group was statistically significantly higher relative to the LVM only treatment group.

Figure 5.

Increased arteriogenesis and myofibroblast infiltration in the infarct region. Arteriole staining was performed in the infarct area for PBS (a), LVM only (b), and LVM-PPy (c) treatment groups. Magnification is at 10X. The bar represents 100 µm. (d) Graph shows means + SD for arteriole density. The degree of myofibroblast infiltration was graded semiquantitatively on a scale from 1 to 5 (e).

We also investigated whether there was a link between biopolymer treatment and myofibroblast population in the infarct region. The level of myofibroblast infiltration was ranked on a scale from 1 to 5 based on percent occupied area in the infarct, where a score of 1 indicated very little or no infiltration and a score of 5 represented at least 50% occupation in the infarct. We defined myofibroblasts as cells that had light cytoplasmic staining and a tendency to aggregate into large clusters and that lacked organization and a visible lumen. Mean myofibroblast scores indicated a statistically significant increase in the population of myofibroblasts between the biopolymer treatment groups and the PBS control group (Fig. 5e). There was no difference in myofibroblast population between the two biopolymer treatment groups.

4. Discussion

The mechanism by which inclusion of PPy can induce a stronger arteriogenic effect is as yet unclear and may be mediated the (electro)chemical property of the PPy or of the LVM-PPy blend. PPy is a polycationic conducting polymer. This particular feature of the polymer may act to attract cells to the infarct region. Studies with neurites have shown that these cells, when grown on PPy films, tend to align themselves to and grow in the direction of the electric field. These cells have also shown enhanced proliferation and differentiation in the presence of an electrical stimulus[10, 11]. Other in vitro studies looking at the effect of electrical stimulation in cultures involving myoblasts showed similar results.[7, 33] The heart contracts and relaxes via conduction of electrical impulses through the cardiac tissue. Conduction is markedly reduced or even lost in the infarct region. The presence of the PPy may act to help restore some conduction through the MI, thereby facilitating growth, and perhaps differentiation, of the cells responsible for arteriole formation. Current studies, in vitro and in vivo, are underway that more specifically investigate and utilize the electroactive properties of PPy, as well as other cationic polymers,—both insulating and conducting—on cell behavior (e.g. growth, migration) and on angiogenesis.

The differences in the observed macroscopic structural morphology suggest that the alginate monomers may be interacting with the PPy. In alginate, the polymer is formed by connecting the G residues via Ca2+ salt bridges. The PPy we are using is doped with organic acids, indicating that the each pyrrole unit has an induced positive charge which can be counter-balanced by either the organic acids or any other negatively charged molecule. As a result, the PPy may also be competing with the Ca2+ for the G residues, thereby altering or interfering with the formation of the salt bridges between the G residues. In other words, the G residues may be able to form weak salt bridges with the PPy.

The in vitro results showed that not only is PPy not detrimental to cell growth and survival but suggested that the presence of the PPy might help to promote cell attachment to the alginate scaffold. Normally, cells have a difficult time adhering to the alginate as they lack any integrin-binding sites for the biopolymer. However, that is not to say that the cells have integrin-binding sites for the PPy, but rather the slight positive charge of the conducting polymer is most likely acting to electrostatically attract the slightly negatively charged cell membrane, thereby bringing the cells close to the scaffold surface and keeping them there long enough to establish attachment sites.

Interestingly, after day 1, we only observed better cell growth relative LVM only for the 0.025% v/v PPy in 2% LVM polymer blend. This result implies that other properties of the polymer scaffold, such as the mechanical stiffness, can influence cell growth. We have seen that higher PPy concentrations act to change the structural morphology of the biopolymer, suggesting that, at least, the mechanical properties of the scaffolds have been altered with the addition of PPy. Previous studies have shown that the mechanical stiffness of the b0069opolymer can affect the proliferation, morphology, and even differentiation of various cell types [21, 34–38]. For many cases, a decrease in the mechanical stiffness had a detrimental effect on cell growth and resulted in fewer spread out cells[34, 38]. In our case, the higher PPy concentrations resulted in less stiff and more fragile matrices. This loss in mechanical integrity may be contributing to the observed loss of enhanced cell growth after day 1.

Myofibroblasts in the infarct region indicate the dynamic remodeling environment characterized by the continual flux of cellular and extracellular matrix components in that region. Myofibroblasts are contractile cells, expressing α-smooth muscle actin, that help to restore the structural integrity in the infarct by turning over fibrillar collagen[39–43]. Their contractile property may contribute to the reduction of the infarct scar[44–46]. Our results indicate that myofibroblast infiltration was significantly higher in the biopolymer treatment groups than in the control group, suggesting that LVM and LVM-PPy both provided an equally suitable matrix environment for cellular influx.

5. Conclusions

This report demonstrates the potential use of conducting polymers to enhance myocardial repair following an ischemic injury. There was a significant increase in arteriogenesis in the LVM-PPy polymer blend compared to either the control group or the LVM treatment group. These in vivo results are consistent with the in vitro studies demonstrating increased attachment and proliferation of the HUVEC cells on the LVM-PPy polymer blend.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Vivek Subramanian of the University of California, Berkeley, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, for the use of his four-point probe set-up, and his students Qintao Zhang and Shong Yin for training on its use. This work was partially funded by Symphony Medical, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anversa P, Li P, Zhang X, Olivetti G, Capasso JM. Ischaemic myocardial injury and ventricular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27(2):145–157. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann DL. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: A combinatorial approach. Circulation. 1999;100:999–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christman KL, Vardanian AJ, Fang Q, Sievers RE, Fok HH, Lee RJ. Injectable fibrin scaffold improves cell transplant survival, reduces infarct expansion, and induces neovasculature formation in ischemic myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christman KL, Fok HH, Sievers RE, Fang Q, Lee RJ. Fibrin glue alone and skeletal myoblasts in a fibrin scaffold preserve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:403–409. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang NF, Yu J, Sievers R, Li S, Lee RJ. Injectable Biopolymers Enhance Angiogenesis after Myocardial Infarction. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1860–1866. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kofidis T, De Bruin JL, Hoyt G, Lebl DR, Tanaka M, Yamane T, Chang CP, Robbins RC. Injectable bioartificial myocardial tissue for large-scale intramural cell transfer and functional recovery of injured heart muscle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedrotty DM, Koh J, Davis BH, Taylor DA, Wolf P, Niklason LE. Engineering skeletal myoblasts: roles of three-dimensional culture and electrical stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(4):H1620–H1626. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00610.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui X, Wiler J, Dzaman M, Altschuler RA, Martin DC. In vivo studies of polypyrrole/peptide coated neural probes. Biomaterials. 2003;24(5):777. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubio Retama J, Lopez Cabarcos E, Mecerreyes D, Lopez-Ruiz B. Design of an amperometric biosensor using polypyrrole-microgel composites containing glucose oxidase. Biosens Bioelectron. 2004;20(6):1111. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotwal A, Schmidt CE. Electrical stimulation alters protein adsorption and nerve cell interactions with electrically conducting biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2001;22(10):1055. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt CE, Shastri VR, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth using an electrically conducting polymer. PNAS. 1997;94(17):8948–8953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.8948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madden JD, Cush RA, Kanigan TS, Hunter IW. Fast contracting polypyrrole actuators. Synth Met. 2000;113(1–2):185. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner B, Georgevich A, Hodgson AG, Liu L, Wallace GG. Polypyrrole-heparin composites as stimulus-responsive substrates for endothelial cell growth. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;44(2):121–129. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199902)44:2<121::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Gu X, Yuan C, Chen S, Zhang P, Zhang T, et al. Evaluation of biocompatibility of polypyrrole in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2004;68A(3):411–422. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abraham D, Jyotsna TS, Subramanyam SV. Polymerization of pyrrole and processing of the resulting polypyrrole as blends with plasticised PVC. J Appl Polym Sci. 2001;81(6):1544–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Toparre L, Fernandez J. Conducting polymer blends: polythiophene and polypyrrole blends with polystyrene and poly (bisphenol A carbonate) Macromolecules. 1990;23(4):1053–1059. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang HL, Fernandez JE. Blends of polypyrrole and poly(vinyl alcohol) Macromolecules. 1993;26(13):3336–3339. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green DW, Leveque I, Walsh D, Howard D, Yang X, Partridge K, et al. Biomineralized Polysaccharide Capsules for Encapsulation, Organization, and Delivery of Human Cell Types and Growth Factors. Advanced Functional Materials. 2005;15(6):917–923. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson NE, Stabler CL, Simpson CP, Sambanis A, Constantinidis I. The role of the CaCl2-guluronic acid interaction on alginate encapsulated βTC3 cells. Biomaterials. 2004;25(13):2603. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill E, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Tissue Engineering Special Feature: Regulating activation of transplanted cells controls tissue regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(8):2494–2499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alsberg E, Anderson KW, Albeiruti A, Franceschi RT, Mooney DJ. Cell-interactive alginate hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. J Dent Res. 2001;80(11):2025–2029. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800111501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowley JA, Madlambayan G, Mooney DJ. Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials. 1999;20(1):45. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinsen A, Skjåk-Bræk G, Smidsrød O. Alginate as immobilization material. I. correlation between chemical and physical properties of alginate gel beads. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1989;33(1):79–89. doi: 10.1002/bit.260330111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berridge MV, Tan AS. Characterization of the cellular reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT): Subcellular localization, substrate dependence, and involvement of mitochondrial electron transport in MTT reduction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;303:474–482. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cory AH, Owen TC, Barltrop JA, Cory JG. Use of an aqueous soluble tetrazolium/formazan assay for cell growth assays in culture. Cancer Commun. 1991;3:207–212. doi: 10.3727/095535491820873191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sievers RE, Schmiedl U, Wolfe CL, Moseley ME, Parmley WW, Brasch RC, Lipton MJ. A model of acute regional myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in the rat. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10:172–181. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfe CL, Moseley ME, Wikstrom MG, Sievers RE, Wendland MF, Dupon JW, Finkbeiner WE, Lipton MJ, Parmley WW, Brasch RC. Assessment of myocardial salvage after ischemia and reperfusion using magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Circulation. 1989;80:969–982. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu B, Sun Y, Sievers RE, Browne AE, Lee RJ, Chatterjee K, Parmley WW. Effects of different durations of pretreatment with losartan on myocardial infarct size, endothelial function, and vascular endothelial growth factor. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2001;2(2):129–133. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2001.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu B, Sun Y, Sievers RE, Browne AE, Pulukurthy S, Sudhir K, Lee RJ, Chou TM, Chatterjee K, Parmley WW. Comparative effects of pretreatment with captopril and losartan on cardiovascular protection in a rat model of ischemia reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:787–795. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00592-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takagawa J, Zhang Y, Wong ML, Sievers RE, Kapasi NK, Wang Y, et al. Myocardial infarct size measurement in the mouse chronic infarction model: comparison of area- and length-based approaches. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(6):2104–2111. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00033.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virag JI, Murry CE. Myofibroblast and Endothelial Cell Proliferation during Murine Myocardial Infarct Repair. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(6):2433–2440. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63598-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellar RS, Landeen LK, Shepherd BR, Naughton GK, Ratcliffe A, Williams SK. Scaffold based three-dimensional human fibroblast culture provides a structural matrix that supports angiogenesis in infarcted heart tissue. Circulation. 2001;104:2063–2068. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bach AD, Beier JP, Stark GB. Expression of Trisk 51, agrin and nicotinic-acetycholine receptor epsilon-subunit during muscle development in a novel three-dimensional muscle-neuronal co-culture system. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(2):263–274. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0757-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Genes NG, Rowley JA, Mooney DJ, Bonassar LJ. Effect of substrate mechanics on chondrocyte adhesion to modified alginate surfaces. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;422(2):161. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kong HJ, Alsberg E, Kaigler D, Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Controlling Degradation of Hydrogels via the Size of Crosslinked Junctions. Advanced Materials. 2004;16(21):1917–1921. doi: 10.1002/adma.200400014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowley JA, Mooney DJ. Alginate type and RGD density control myoblast phenotype. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60(2):217–223. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingber DE, Folkman J. Mechanochemical switching between growth and differentiation during fibroblast growth factor-stimulated angiogenesis in vitro: role of extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1989;109(1):317–330. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H-B, Dembo M, Wang Y-L. Substrate flexibility regulates growth and apoptosis of normal but not transformed cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279(5):C1345–C1350. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darby I, Skalli O, Gabbiani G. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is transiently expressed by myofibroblasts during experimental wound healing. Lab Invest. 1990;63(1):21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabbiani G, Hirschel BJ, Ryan GB, Statkov PR, Majno G. Granulation tissue as a contractile organ: A study of structure and function. J Exp Med. 1972;135(4):719–734. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.4.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Y, Kiani MF, Postlethwaite AE, Weber KT. Infarct scar as living tissue. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97(5):343–347. doi: 10.1007/s00395-002-0365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, Weber KT. Infarct scar: a dynamic tissue. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46(2):250. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willems IE, Havenith MG, De Mey JG, Daemen MJ. The alpha-smooth muscle actin-positive cells in healing human myocardial scars. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(4):868–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agbulut O, Menot ML, Li Z, Marotte F, Paulin D, Hagege AA, Chomienne C, Samuel JL, Menasche P. Temporal patterns of bone marrow cell differentiation following transplantation in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:451–459. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jugdutt BI. Remodeling of the Myocardium and Potential Targets in the Collagen Degradation and Synthesis Pathways. Current Drug Targets -Cardiovascular & Haematological Disorders. 2003;3:1. doi: 10.2174/1568006033337276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jugdutt BI. Ventricular Remodeling After Infarction and the Extracellular Collagen Matrix: When Is Enough Enough? Circulation. 2003;108(11):1395–1403. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085658.98621.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]