Abstract

Five pathologic variants of FSGS were recently defined (“Columbia classification”), but the stability of these phenotypes in renal allografts remains unknown. We hypothesized that if the variants represent distinct diseases, then the pattern of recurrent FSGS in renal allografts will mimic the original disease in the native kidney. This multicenter study included 21 cases of recurrent FSGS from 19 patients who had both native and transplant biopsy samples available for analysis. These results support the Columbia classification, because 81% recurred in the same pattern as the original disease, but three variants manifested plasticity from native to allograft kidneys or in the pattern of recurrence (four FSGS, not otherwise specified [NOS] to collapsing variant, two collapsing variant to FSGS NOS, and one cellular variant to FSGS NOS). No transitions between the cellular and the collapsing variants were observed, supporting the view that these are separate entities. Three categories of recurrence were observed: Type I, recurrence of the same variant of FSGS; type II, recurrence of the same FSGS variant, preceded by a minimal change–like lesion; and type III, recurrence of a different FSGS variant in the allograft. Thus, potential evolution of the pathologic phenotype should be considered in pathologic interpretation and clinical trials.

Primary FSGS is a common cause of ESRD in adults and children. Patients with FSGS present with proteinuria, usually in the nephrotic range, and approximately 30 to 50% of all patients with FSGS progress to ESRD.1,2 FSGS is a disease with many different forms, in terms of clinical features, outcome, and morphology.3 On the basis of glomerular morphology, D'Agati et al.4 proposed a classification of FSGS variants termed the Columbia classification that distinguishes five variants of FSGS: (1) the tip lesion variant, a lesion located near the origin of the proximal convoluted tubule; (2) the cellular variant, characterized by endocapillary hypercellularity; (3) the collapsing variant, showing collapse of the glomerular tuft concomitant with epithelial cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia; (4) the perihilar variant, a lesion predominantly located at the vascular pole; and (5) FSGS not otherwise specified (NOS).

Clinical features and prognosis differ for these FSGS variants.5 For example, patients with a tip lesion generally present with severe nephrotic syndrome but are steroid sensitive and have the highest rate of complete remission and renal survival.5 In contrast, patients with a collapsing variant are usually steroid resistant and have the worst prognosis with rapid progression to renal insufficiency.5 It is expected that the FSGS classification will lead to more appropriate treatment of the variants of FSGS.

A large proportion of patients with FSGS develop ESRD, and some of them receive a renal transplant.1 After kidney transplantation, approximately 30% of these patients develop recurrent FSGS.6 Swaminathan et al.7 showed in a group of 29 patients that the clinical features and morphology of collapsing FSGS in renal allografts were identical to the primary collapsing FSGS. Similar investigations have not yet been performed for the other variants of FSGS. We wished to test the hypothesis that the subclasses of FSGS are indeed separate etiologic and pathogenetic entities. In this study, we investigated whether the same subclass of FSGS consistently recurred in renal transplants. In addition, the transplanted and native kidneys provided an opportunity to observe the evolution of morphologic features over time.

RESULTS

Patients

The demographics of the 19 patients are shown in Table 1. All patients except patients 6 and 13 were white. Patient 6 was Asian, and patient 13 was Middle East Arab. The patients, 14 male and five female, had a median age of 35 yr (range 2 to 59) at the time of FSGS diagnosis. All patients had nephrotic-range proteinuria (>3.5 g/24 h) during the initial phase of the disease. Seventeen patients developed recurrent FSGS in their first allografts. Of these 17, two also developed recurrent disease in a second renal allograft. One patient developed a recurrence in his second allograft after having rejection with necrosis in his first allograft. One patient showed a minimal change–like lesion (MC) with nephrotic-range proteinuria 5 d after transplantation. The median age at time of first recurrence was 38 yr (range 3 to 61). All patients with recurrence were treated supportively with standard posttransplantation immunosuppression and care except for two patients with a recurrence shortly after transplantation (patients 5 and 11), who were treated with courses of plasma exchange.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Characteristics | Total (Range) |

|---|---|

| No. of patients (female/male) | 19 (5/14) |

| Age at original diagnosis (yr; median [range]) | 35 (2 to 59) |

| Time on dialysis before first transplant (mo; median [range]) | 22 (5.7 to 79) |

| Age at first transplant (yr; median [range]) | 38 (3 to 60) |

| Age of transplant biopsy (yr; median [range]) | 38 (3 to 61) |

| Time to first post-transplant biopsy (d; median [range]) | 108 (2 to 4015) |

Histologic Variants in the Native Kidney

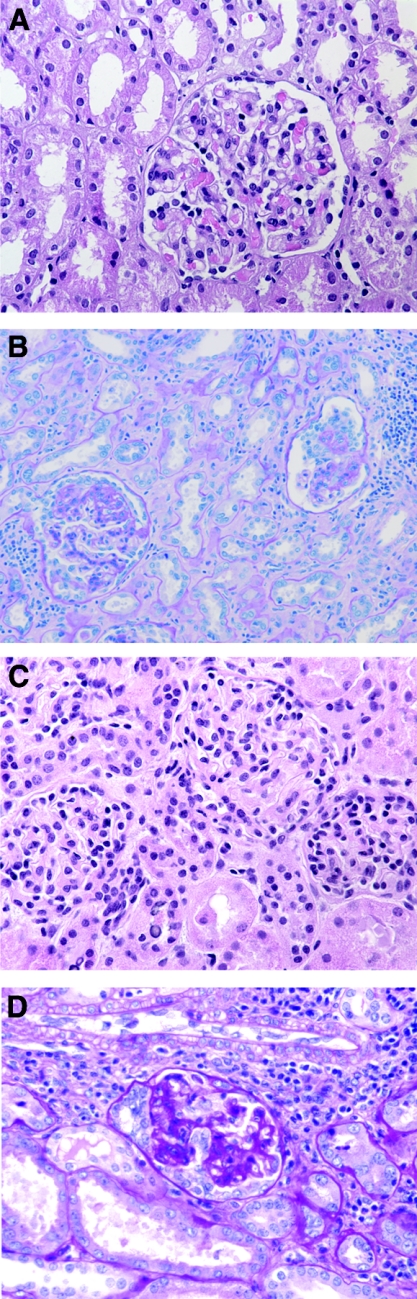

Twenty-six samples from 19 patients were available (Table 2). Sixteen patients had a single sample taken from the native kidney. Of these 16 patients, FSGS NOS was present in eight; five had the collapsing variant, two the cellular variant, and one the tip lesion variant without segmental sclerosing lesions. Three patients had multiple biopsies of their native kidneys. Patient 8 had an MC in the first biopsy, whereas the second biopsy showed FSGS NOS, and this patient had an allograft recurrence of the collapsing FSGS variety. Patient 11 had an MC, FSGS NOS, and collapsing FSGS in his first, second, and third biopsies, respectively. Figure 1 depicts minimal change–like lesions and collapsing variant in patient 11. Patient 17 had cellular FSGS in his first biopsy and FSGS NOS in a follow-up biopsy, indicating that subclass evolution can occur in native kidneys to or from the FSGS NOS category. For the purpose of this study, the subclass of the last sample obtained was considered the defining subclass of the patient's original disease.

Table 2.

Clinical and histologic characteristics of specimens from each patienta

| Patient | Gender | Native Kidney

|

Transplant

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | Indication(s) | Proteinuriab | Variant | No. of glomeruli | IF | EM | Age at biopsy (yr) | Time to biopsy (d) | Indication(s) | Proteinuriab | Variant | No. of glomeruli | IF | EM | ||

| 1 | M | 19 | P/Cr | 7.2 | Collapsing | 14 | IgM, C3, C1q | NA | 23 | 120 | Np, Cr | NA | Collapsing | 17 | NA | NA |

| 425 | Cr | 8.9 | Collapsing | 10 | IgM | FP | ||||||||||

| 26c | 3c | Crc | 2c | MCc | 42c | NAc | FPc | |||||||||

| 2 | M | 52 | P | NA | Cellular | 8 | NA | NA | 61 | 45 | Cr | 3.3 | Cellular | 17 | IgM, IgA | NA |

| 3 | M | 35 | Np | 24 | Cellular | >25 | IgA, IgM | NA | 38 | 30 | Cr | 10 | Cellular | 6 | No | FP |

| 39 | 150 | Np/Cr | 17 | Cellular | Ne | NA | NA | |||||||||

| 4 | F | 27 | Ne | NA | NOS | A | NA | NA | 18 | 150 | Np | NA | NOS | 7 | IgG, IgA, IgM | NA |

| 23c | 1460c | Crc | 2c | NOSc | >25c | Noc | NAc | |||||||||

| 5 | F | 24 | Np | 8.7 | NOS | 20 | IgM | NA | 31 | 10 | Cr/P | 9 | NOS | 17 | NA | FP |

| 6 | M | 36 | P | NA | NOS | 8 | IgM, C3 | NA | 45 | 2555 | P | 2.3 | NOS | 5 | No | NA |

| 7 | M | 13 | Np | NA | Collapsing | 30 | IgM, IgG, C3, C1q | NA | 20 | 548 | Np, Cr | 6 | NOS | 5 | IgM | NA |

| 8 | F | 2 | NA | 10.4 | MC | 15 | Neg | NA | 16 | 4015 | Cr | NA | Collapsing | 13 | Neg | NA |

| 2 | NA | 2.8 | NOS | 6 | NA | NA | ||||||||||

| 3 | NA | 3.24 | NOS | Ne | NA | NA | ||||||||||

| 9e | M | 45 | NA | NA | Tip lesion | 30 | NA | NA | 57 | 5 | Np, Cr | 6 | MC | 10 | Neg | FP |

| 10 | F | 39 | Ne | 3+ | NOS | Ne | IgM, C3 | NA | 40 | 393 | P, Cr | 4.5 | NOS | >25 | IgM, C3 | FP |

| 42 | 1043 | Cr | 3+ | NOS | 17 | IgM, C3 | FP | |||||||||

| 11 | M | 6 | Np | 3+ | MC | 12 | IgM | FP | 7 | 2 | P, R | 6.1 | MC | >25 | IgM, C3 | FP |

| 6 | Np | 6.4 | NOS | >25 | NA | FP | 8 | 389 | Np | 11.8 | Collapsing | Ne | IgM, C3 | FP | ||

| 7 | Np | 13.7 | Collapsing | Ne | IgM, C3 | FP | ||||||||||

| 7 | Np | 8.4 | Collapsing | Ne | IgM, C3 | NA | ||||||||||

| 12 | M | 49 | Ne | 2.3 | Collapsing | Ne | IgM, C3 | FP | 49 | 4 | P | 10.0 | MC | 13 | IgM, C3 | FP |

| 49 | 7 | R | 4.7 | Collapsing | 3 | IgM, C3 | FP | |||||||||

| 49 | 63 | P, R | 20.0 | Collapsing | 8 | NA | NA | |||||||||

| 51 | 645 | Np, Ne | 10.3 | Collapsing | Ne | NA | NA | |||||||||

| 13 | M | 37 | P | NA | Collapsing | 9 | IgM, C3 | FP | 40 | 206 | Cr | 14.4 | Collapsing | 7 | IgM, C3 | FP |

| 14 | F | 54 | P | 9.2 | NOS | 9 | IgM, C3 | FP | 56 | 237 | P, Cr, R | 10.3 | Collapsing | 5 | IgM, C3 | FP |

| 58 | 824 | R | 15.7 | NOS | 4 | NA | FP | |||||||||

| 15 | M | 25 | NA | NA | Collapsing | Ne | NA | NA | 25 | 16 | NA | 1+ | Rejection | 7 | NA | NA |

| 25 | 255 | NA | 3+ | Necrosisd | Ne | NA | NA | |||||||||

| 25c | 53c | NAc | NAc | MCc | 8c | NAc | FPc | |||||||||

| 26c | 347c | NAc | 4+c | NOSc | 12c | NAc | NAc | |||||||||

| 16 | M | 45 | NA | NA | NOS | Ne | C3 | NA | 55 | 354 | R | 3.8 | NOS | 5 | IgM, C3 | FP |

| 57 | 851 | P, R | 3.8 | NOS | 4 | NA | FP | |||||||||

| 17 | M | 3 | P | 3.2 | Cellular | >25 | NA | NA | 15 | 7 | P, Cr | 17.9 | MC | 12 | NA | FP |

| 15 | Ne | 10.8 | NOS | Ne | IgM, C3 | FP | 19 | 1183 | Cr | 13.9 | NOS | 15 | IgM, C3 | FP | ||

| 15 | Ne | 10.8 | NOS | Ne | IgM, C3 | FP | ||||||||||

| 18 | M | 3 | NA | Y | NOS | >25 | C3 | NA | 3 | 24 | NA | 2+ | MC | >25 | NA | FP |

| 7 | 1470 | NA | 1.0 | NOS | 2 | NA | NA | |||||||||

| 19 | M | 59 | Ne | 2+ | NOS | Ne | IgM, C3 | NA | 59 | 108 | P | 5.0 | Collapsing | 2 | IgM, C3 | FP |

C1q: segmental C1q; C3, segmental C3; Cr, elevated creatinine; EM, electron microscopy; F, female; FP, foot process effacement; IF, immunofluorescence; IgA, segmental IgA; IgG, segmental IgG; IgM, segmental IgM; M, male; NA, data not available; Ne, nephrectomy; Neg, no immune deposition in IF; Np, nephrotic syndrome; P, proteinuria; R, r/o rejection.

Proteinuria measured in g/24 h or on a scale from 0 to 4+.

Second transplant.

Nephrectomy showed severe necrosis.

First two grafts were lost as a result of primary nonfunction.

Figure 1.

Representative histologic pictures of renal biopsies of patient 11. Both in native and transplant kidney, minimal change–like lesions are present in the first biopsy, followed by development of collapsing FSGS at a later time point. (A) Minimal change–like lesion in native kidney. (B) Collapsing FSGS in nephrectomy of native kidney. (C) Minimal change–like lesion a few days after renal transplantation. (D) Collapsing FSGS in renal allograft nephrectomy.

Histologic Variants of Recurrent FSGS

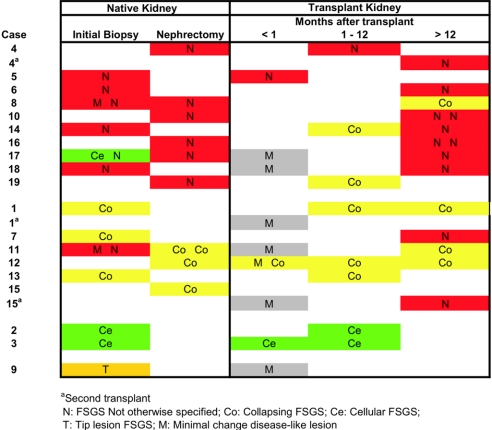

Eight (80%) of 10 patients with FSGS NOS in their native kidneys also had FSGS NOS in at least one renal biopsy specimen from their allografts. Three of these eight patients had a different variant of FSGS before the biopsy that showed FSGS NOS. One patient had biopsy-proven collapsing FSGS in the first year after transplantation and FSGS NOS 1.5 yr later. Two patients had an MC within 3 wk of transplantation and >3 yr later had FSGS NOS. Neither patient had an intervening biopsy between the biopsy that showed an MC in the allograft and those showing FSGS NOS. Patient 8 had a collapsing variant 108 d after transplantation. Patient 19 also had collapsing FSGS in his renal transplant biopsy at a very late stage.

Of 6 patients with collapsing FSGS in the native kidney, four showed a recurrence of collapsing FSGS in at least one renal transplant biopsy. Of these four patients, two presented with an MC 2 d (patient 11; Figure 1, C and D) and 4 d after transplantation; a biopsy taken only 3 d later showed collapsing FSGS in one of these two patients (patient 12). Another patient had a recurrence of collapsing FSGS in his first renal transplant, resulting in graft loss. This patient had a second graft and developed nephrotic syndrome 3 d after transplantation; at this point, a biopsy showed an MC. Two of the 6 patients with collapsing FSGS in their native kidneys developed FSGS NOS in their renal allografts. Interestingly, one patient with recurrent collapsing FSGS had multiple biopsies of his renal allograft that showed collapsing FSGS at 7, 63, and 645 d after transplantation.

Two patients with the cellular variant of FSGS in their native kidneys also had the cellular variant of FSGS in their allografts. The patient with the tip lesion variant in the native kidney had an MC in his renal transplant biopsy 5 d after transplantation.

We identified three distinct patterns of recurring FSGS (Table 3): Type I, recurrence of the same variant of FSGS (n = 11); type II, recurrence of the same variant of FSGS after an intermediate stage with an MC (n = 4); and type III, recurrence of a different FSGS variant in the allograft than in the native kidney (n = 4). Types I and II are regarded as recurrences with fidelity and represent 17 (81%) of 21 of the allografts in the series. Type III cases (19%) were further divided into early (<1 yr) and late (>1 yr) recurrences with disparate variants, because late FSGS can have other causes, such as calcineurin inhibitor toxicity. Two patterns of FSGS in allografts could not be classified into one of the three types of recurring FSGS. The second allograft of patient 1 and the allograft of patient 9 showed MC. Follow-up of both allografts was <1 mo (type IV).

Table 3.

Recurrence classification

| Types of Recurrence | n | Patient |

|---|---|---|

| I. Fidelity to native disease | ||

| type X FSGS → type X FSGS | 11 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 4a, 5, 6, 10, 13, 14d, 16 |

| II. Fidelity to native disease after MC intermediateb | ||

| type X FSGS → MC → type X FSGS | 4 | 11, 12, 17, 18 |

| III. Lack of fidelity to native diseasec | ||

| type X FSGS → type Y FSGS | ||

| early (<1 yr) | 2 | 15, 19 |

| late (>1 yr) | 2 | 7, 8 |

| IV. Less than 1 mo of follow-up | 2 | 1a, 9 |

Second transplant.

Two native kidneys had this sequence before transplantation (MC → FSGS; 8 and 11).

Three native kidneys also changed type before transplantation (9, 11, and 17).

Fidelity to native disease after collapsing intermediate.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated whether the histologic variant of FSGS in patients with recurrent FSGS in their allograft was similar to the variant in their native kidneys. We studied 19 patients with recurrent FSGS, and an interesting pattern of recurrence of FSGS emerged (Figure 2). Both the collapsing and cellular variants recurred in their native forms, and there was no exchange between these two types or evolution from one to the other. Only one patient with a tip lesion variant in the native biopsy developed an MC early after transplantation. Interestingly, other forms of FSGS also presented with an MC in the early renal transplant biopsies, followed by FSGS at later time points. FSGS NOS generally recurred as FSGS NOS; the exceptions were patients 8 and 19, who developed collapsing FSGS in their allografts after FSGS NOS in their native kidneys. Two patients with collapsing FSGS in their native kidneys developed FSGS NOS in their renal transplants but only at a later time point (approximately 1 yr after transplantation). Our results are compatible with those of Swaminathan et al.,7 who reported that the collapsing variant recurred as collapsing in two of two patients, and noncollapsing variants in eight of eight patients recurred as noncollapsing FSGS (not further subdivided).

Figure 2.

FSGS variants in patients’ native and transplant kidneys. For each patient, the FSGS variant and time to biopsy after transplantation are shown.

Several interesting observations were made in this study. First, we observed that cellular and collapsing forms of FSGS are not exchanged (i.e., they recur in their native forms in the renal transplant). This supports the hypothesis that these types of FSGS are indeed separate disease entities, most likely with their own pathogenetic backgrounds. The relationship between the cellular and the collapsing variants of FSGS is somewhat controversial,8,9 and some investigators do not distinguish between these subtypes.10 Indeed, the cellular variant requires previous exclusion of the collapsing variant, and these two forms may present together within the same renal biopsy sample. This could either be interpreted as a sign of comorbidity or that the two variants represent one end of a spectrum. In favor of the view that they are two separate entities, data from Stokes et al.8 showed that the collapsing variant has a higher rate of ESRD and a lower rate of remission. Our findings of FSGS in the renal transplants also support this view. More studies are needed to determine the clinical importance of distinguishing between cellular and collapsing variants in allografts.

Second, our data show that FSGS NOS represents a late phase of a number of variants of FSGS; however, the recurrence of FSGS NOS in the renal transplants in two patients within 10 and 150 d after transplantation, respectively, seems to indicate that FSGS NOS should also be regarded as an entity in itself. Especially for FSGS NOS, careful attention is required for exclusion of another primary disease associated with FSGS and FSGS secondary to chronic allograft nephropathy or calcineurin inhibitors.11 Howie et al.12 showed that FSGS NOS could occur in a later stage of patients with tip lesions. In our study, only one patient had the tip lesion variant of FSGS in the native kidney. We had only very short follow-up data for this patient, but a biopsy taken 5 d after transplantation showed an MC. This suggests that an MC can precede the tip lesion variant of FSGS. In the study by Howie et al.,12 the tip lesion variant of FSGS transformed to FSGS NOS in many subsequent biopsies, in both the native and the transplant kidneys; however, some patients with FSGS NOS in the native kidney showed the tip lesion variant in the renal transplant biopsy. The continuum of MC to tip lesion FSGS to FSGS NOS may explain why some patients with a tip lesion are better responders to steroids and others progress to ESRD. Others have expressed that the tip lesion may not be a specific form of FSGS but rather a response to persistent heavy proteinuria.13

Third, our data provide evidence for an MC as an early phase of FSGS variants other than the tip lesion variant. In two patients, collapsing FSGS and FSGS NOS development in the native kidney was preceded by a histologic diagnosis of an MC in earlier biopsy samples. In one of these patients and four others, an MC preceded the development of collapsing FSGS and FSGS NOS in the allograft as well. The hypothesis that an MC is an early phase of FSGS has been a source of debate.14,15 Our study provides evidence in favor of an MC as the early phase of FSGS.

This retrospective study has some drawbacks, particularly in terms of distinguishing an MC from FSGS. FSGS studies often have a problem with sampling errors because of the nature of the lesions. In the study by Chun et al.,1 for example, inclusion criteria included a minimum of five glomeruli per biopsy sample; however, others have suggested that >25 glomeruli should be present in a biopsy to detect a lesion that occurs in approximately 10% of all glomeruli in the kidney.16,17 Cases classified as collapsing glomerulopathy would not change their classification even if the sample size number were increased, but for FSGS NOS and MC, a relatively small sample size may be inadequate because the classification would change if only one glomerulus would show, for instance, a cellular or collapsing lesion. Determinations on the number of glomeruli needed for analysis depends on the frequency of the focal lesion. In addition, sampling of the corticomedullary junction has been shown to be most effective in demonstrating FSGS lesions. If this region is not sampled, then FSGS lesions may be missed; therefore, in this study, sampling error could be one source of error. All biopsies in which an MC was diagnosed had at least eight glomeruli per biopsy in this study. Another drawback is that the time points after transplantation were variable, because all biopsies were performed for clinical reasons. To study, for example, the development of an MC to FSGS in greater detail, it would be necessary to have biopsies at specific time points written into the study protocol. It is possible that the histologic variants in renal transplants could have been influenced by immunosuppressive therapy or by other transplantation-related changes, such as infection susceptibility. For instance, the presence of collapsing FSGS as a de novo disease in renal transplantation could be related to viral infections such as parvovirus infection18 or to calcineurin inhibitor toxicity.19 None of our patients with a collapsing variant in their renal allograft biopsies had known related infections. Of the patients with a collapsing FSGS in the renal transplant, three received calcineurin inhibitors, two did not, and two had uncertain data. Interestingly, the patient in whom a change in classification occurred (patient 19) was one of the patients who did not receive calcineurin inhibitors. Also, although our study did not knowingly include de novo FSGS, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the cases of FSGS that were manifested >1 yr after transplantation were actually de novo FSGS. This may have been the case for the two patients who were disparate in subclass. Finally, our study did not include patients with perihilar FSGS. The lack of this variant probably reflects its recurrence infrequency, because it is usually secondary to hypertension and other causes. Thus, we cannot draw any conclusion on this variant of FSGS. The small number of cases of the cellular and tip variant also limit conclusions on these subgroups.

In conclusion, we identified three distinct patterns of recurrent FSGS in renal transplants. Our findings substantially support the relevance and consistency of the Columbia subclassification for renal transplant biopsies, allowing for some evolution through an MC and transformation between NOS and other categories. Our findings point toward a patient-related pathogenetic mechanism in the development of the various subclasses of FSGS.

CONCISE METHODS

From the clinical and histologic databases from the Erasmus Medical Center (Rotterdam), Leiden University Medical Center (Leiden), Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston), University Medical Center Utrecht (Utrecht), and University Medical Center Groningen (Groningen), 19 patients who had received a diagnosis of recurrent FSGS and had biopsies or nephrectomies in both the native kidney and the allograft were identified. Twelve nephrectomy samples from 10 patients and 14 biopsy samples from 12 patients were available for the native kidneys. Four nephrectomy samples and 31 biopsy samples were available for the allografts. Adequate pathologic material was available from all included patients. The median number of glomeruli per biopsy was 11 (range 2 to >25). The diagnosis of primary FSGS was made when there was no pathologic evidence for a primary glomerular disease or systemic disease process that might produce secondary segmental glomerular sclerosis. FSGS was classified using hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Jones’ methenamine-silver staining according to the Columbia Criteria.4 Clinical data were obtained from standardized physician referral forms submitted with the biopsy specimens, the patients’ medical charts, and clinical databases.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chun MJ, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in nephrotic adults: Presentation, prognosis, and response to therapy of the histologic variants. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2169–2177, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valeri A, Barisoni L, Appel GB, Seigle R, D'Agati V: Idiopathic collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A clinicopathologic study. Kidney Int 50: 1734–1746, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Agati V: The many masks of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 46: 1223–1241, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Agati VD, Fogo AB, Bruijn JA, Jennette JC: Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 368–382, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas DB, Franceschini N, Hogan SL, Ten Holder S, Jennette CE, Falk RJ, Jennette JC: Clinical and pathologic characteristics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants. Kidney Int 69: 920–926, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colvin R.: Renal transplant pathology. In: Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney, 5th Ed., edited by Jennette JC, Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 2007, pp 1409–1540

- 7.Swaminathan S, Lager DJ, Qian X, Stegall MD, Larson TS, Griffin MD: Collapsing and non-collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in kidney transplants. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 2607–2614, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokes MB, Valeri AM, Markowitz GS, D'Agati VD: Cellular focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Clinical and pathologic features. Kidney Int 70: 1783–1792, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair R: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Cellular variant and beyond. Kidney Int 70: 1676–1678, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz MM, Evans J, Bain R, Korbet SM: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Prognostic implications of the cellular lesion. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1900–1907, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadasdy T, Allen C, Zand MS: Zonal distribution of glomerular collapse in renal allografts: Possible role of vascular changes. Hum Pathol 33: 437–441, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howie AJ, Pankhurst T, Sarioglu S, Turhan N, Adu D: Evolution of nephrotic-associated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and relation to the glomerular tip lesion. Kidney Int 67: 987–1001, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howie AJ: Changes at the glomerular tip: A feature of membranous nephropathy and other disorders associated with proteinuria. J Pathol 150: 13–20, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogo A, Hawkins EP, Berry PL, Glick AD, Chiang ML, MacDonell RC Jr, Ichikawa I: Glomerular hypertrophy in minimal change disease predicts subsequent progression to focal glomerular sclerosis. Kidney Int 38: 115–123, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyrier A: Mechanisms of disease: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 1: 44–54, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corwin HL, Schwartz MM, Lewis EJ: The importance of sample size in the interpretation of the renal biopsy. Am J Nephrol 8: 85–89, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madaio MP: Renal biopsy. Kidney Int 38: 529–543, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moudgil A, Nast CC, Bagga A, Wei L, Nurmamet A, Cohen AH, Jordan SC, Toyoda M: Association of parvovirus B19 infection with idiopathic collapsing glomerulopathy. Kidney Int 59: 2126–2133, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goes NB, Colvin RB: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 12–2007. A 56-year-old woman with renal failure after heart-lung transplantation. N Engl J Med 356: 1657–1665, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]