Abstract

C1q nephropathy is an uncommon glomerular disease with characteristic features on immunofluorescence microscopy. In this report, clinicopathologic correlations and outcomes are presented for 72 patients with C1q nephropathy. The study comprised 82 kidney biopsies from 28 children and 54 adults with male preponderance (68%). Immunofluorescence microscopy showed dominant or co-dominant staining for C1q in the mesangium and occasional glomerular capillary walls. Electron-dense deposits were observed in 48 of 53 cases. Light microscopy revealed no lesions (n = 27), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS; n = 11), proliferative glomerulonephritis (n = 20), or various other lesions (n = 14). Clinical presentations in the patients who had no lesions histology were normal urine examination (7%), asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria (22%), and nephrotic syndrome (minimal change-like lesion; 63%), which frequently relapsed. All patients with FSGS presented with nephrotic syndrome. Those with proliferative glomerulonephritis usually presented with chronic kidney disease (75%) or asymptomatic urine abnormalities (20%). Of the patients with sufficient follow-up data, complete remission of the nephrotic syndrome occurred in 77% of those with a minimal change–like lesion, progression to end-stage renal disease occurred in 33% of those with FSGS, and renal disease remained stable in 57% of those with proliferative glomerulonephritis. In conclusion, this study identified two predominant clinicopathologic subsets of C1q nephropathy: (1) Podocytopathy with a minimal change–like lesion or FSGS, which typically presents with nephrotic syndrome, and (2) a typical immune complex–mediated glomerular disease that varies from no glomerular lesions to diverse forms of glomerular proliferation, which typically presents as chronic kidney disease. Clinical presentation, histology, outcomes, and presumably pathogenesis of C1q nephropathy are heterogeneous.

C1q nephropathy was described by Jennette and Hipp1 in 1985, defined by conspicuous C1q in glomerular immune deposits in patients with no evidence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The exclusion criteria also include type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, which frequently has substantial C1q staining in the glomerular immune deposits.2 The prevalence of C1q nephropathy among patients who have undergone renal biopsy varies from 0.2 to 16.0% and seems to be higher in children.3,4

C1q nephropathy often manifests as steroid-resistant asymptomatic proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome.1,3–5 Light microscopic features are heterogeneous and comprise no glomerular lesions, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and proliferative glomerulonephritis.1,3,4,6 The pathologic features, clinical presentations, and outcomes are based on only a few small studies.3,4,6–9 Patients with nephrotic syndrome, particularly those with FSGS, showed a poor response to corticosteroid therapy, whereas patients presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities maintained normal renal function.3,4,8,9 Additional studies are needed to elucidate this heterogeneous glomerular disease.

RESULTS

We studied 72 patients with C1q nephropathy, representing a 1.9% prevalence among native kidney biopsies of children and adults from 1985 through 2005. The cohort included 17 boys and 11 girls (aged 2 to 17 yr; mean 10.4 ± 4.5) and 32 men and 12 women (aged 18 to 66 yr; mean 30.2 ± 11.8), thus a male preponderance of 68.1%. All patients were white. Demographic data, clinical presentations, and histology are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Histologic diagnosis in relation to clinical presentation at the first renal biopsy for 72 patients with C1q nephropathya

| Demographic and Clinical Features | Light Microscopy Findings

|

Pc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Lesions (n = 10) | No Lesions (with NS) (n = 17) | FSGS (with NS) (n = 11) | Proliferative GN (n = 20) | Otherb (n = 14) | ||

| Age range (yr) | 11 to 60 | 2 to 33 | 4 to 35 | 9 to 66 | 7 to 58 | |

| Mean age (yr; mean ± SD) | 26.3 ± 15.0 | 16.2 ± 10.0 | 17.9 ± 10.4 | 27.9 ± 14.4 | 22.5 ± 14.5 | 0.0020 |

| Children/adults | 4/6 | 8/9 | 6/5 | 4/16 | 6/8 | 0.0490 |

| Male/female | 7/3 | 8/10 | 7/4 | 18/2 | 9/5 | 0.0090 |

| Underlying infections (n [%])d | 2 (20.0) | 11 (64.7) | 3 (27.3) | 8 (40.0) | 3 (21.4) | 0.3060 |

| Urinalysis normal (n [%]) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (14.3) | 0.1570 |

| Hematuria (n [%]) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (58.8) | 6 (54.5) | 19 (95.0) | 9 (64.3) | 0.0020 |

| Non–nephrotic-range proteinuria (n [%]) | 6 (60.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (70.0) | 7 (50.0) | 0.0005 |

| NS or nephrotic-range proteinuria (n [%]) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) | 5 (25.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0.0005 |

| Renal insufficiency (n [%]) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (17.6) | 5 (45.5) | 15 (75.0) | 8 (57.1) | 0.0560 |

| Hypertension (n [%]) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (11.8) | 4 (36.4) | 11 (55.0) | 6 (42.9) | 0.0760 |

GN, glomerulonephritis; NS, nephrotic syndrome.

Tubulointerstitial nephritis (n = 6), Hantavirus nephropathy (n = 1), benign hypertensive nephrosclerosis (n = 2), thin basement membrane nephropathy (n = 3), autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (n = 1), and medullary cystic disease (n = 1).

For statistical analysis, the groups “no lesions (with NS)” and “FSGS (with NS)” were merged, as were “no lesions” and “proliferative GN.” The group “other” was not considered for statistical analysis.

Underlying infections: Pharyngitis or tonsillitis (n = 17), bronchopneumonia (n = 4), diarrhea (n = 2), erysipelas (n = 1), meningitis (n = 1), meningoencephalitis (n = 1), and encephalitis (n = 1).

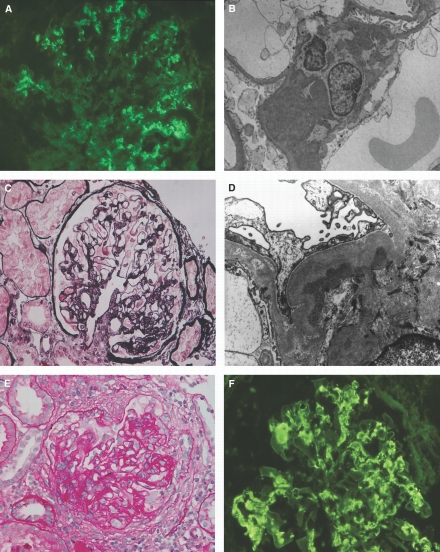

Light Microscopy and Clinical Presentation

According to light microscopy, C1q nephropathy cases were grouped as no lesions, FSGS, proliferative glomerulonephritis, and other (Table 1). The group of no lesions (Figure 1, A and B) included 17 individuals who presented with nephrotic syndrome (10 of 17 relapsing nephrotic syndrome), six with asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria, one with acute renal failure, one with chronic kidney disease, and two kidney donors (of 27 kidney donors examined by immunofluorescence microscopy) with normal urine examinations. In the histologic group of FSGS (Figure 1, C and D), occasionally associated with mild mesangial proliferation, all 11 patients presented with nephrotic syndrome (one of 11 relapsing nephrotic syndrome). Twenty patients with various clinical presentations, most frequently chronic kidney disease (75.0%), had proliferative glomerulonephritis with mesangial hypercellularity. Two of them had also segmental endocapillary hypercellularity, one segmental glomerular basement membrane duplication, five extracapillary crescents (Figure 1, E and F), and 11 segmental or global glomerular sclerosis. Two patients with focal proliferative glomerulonephritis had small vessel vasculitis and significant tubulointerstitial inflammation. Fourteen patients had other histologic diagnoses with various clinical presentations: Tubulointerstitial nephritis (n = 6), Hantavirus nephropathy (n = 1), hypertensive nephrosclerosis (n = 2), thin basement membrane nephropathy (n = 3), autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (n = 1), and medullary cystic disease (n = 1). A total of 27 (37.5%) patients had underlying infections, 18 contemporaneous at the time of renal presentation and nine recent, occurring 2 to 6 wk before the presentation of renal disease. There was no correlation between the frequency of underlying infection and the histologic groups of C1q nephropathy (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Pathologic findings in C1q nephropathy. (A and B) A 14-yr-old male patient presenting with asymptomatic hematuria and proteinuria. (A) Immunofluorescence shows global granular mesangial staining for C1q. (B) Electron micrograph displays dense deposits in the mesangium without cell proliferation. (C and D) A 27-yr-old female patient presenting with nephrotic syndrome. (C) A glomerulus displays segmental perihilar glomerular sclerosis, whereas most of the glomeruli (data not shown) were unremarkable (periodic acid silver methenamine/Azan). (D) On electron microscopy, dense deposits are seen in the widened mesangial matrix beneath the glomerular basement membrane. Note also extensive foot process effacement and segmental podocyte-free surface microvillous transformation. (E and F) A 29-yr-old male patient presenting with chronic kidney disease. (E) A glomerulus shows mesangial and endocapillary proliferation accompanied by extensive fibrocellular crescent (periodic acid Schiff). (F) Immunofluorescence shows conspicuous mesangial and segmental capillary wall C1q staining in “full house” pattern glomerular immune deposits. Magnifications: ×400 in A, C, E, and F; ×4400 in B; 10,000 in D.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Table 2 shows immunofluorescence microscopy findings in the initial biopsy or in the second in cases with negative C1q in the initial biopsy. Staining for C1q was dominant or co-dominant in all cases (Figure 1, A and F). A “full house” pattern with deposits of IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, and C3 was found in 22 (30.6%) patients, predominantly in those with proliferative glomerulonephritis (10 of 20 versus 11 of 52; P = 0.026). Granular or lumpy immune deposits were mesangial in 64 and, exclusively in cases with proliferative glomerulonephritis, mesangial and capillary wall in eight. Mesangial immune deposits were global in 51 cases and segmental in 21, present particularly in the perihilar region. Extraglomerular vascular immune deposits were observed in two cases (IgG and C3; IgG, IgM, and C3) with proliferative glomerulonephritis.

Table 2.

Immunofluorescence findings in 72 patients with C1q nephropathy

| Immune Reactants | Frequency (n [%]) | Intensity (Mean ± SD) | Intensity (Median) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | 48 (66.7) | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2 |

| IgM | 58 (80.6) | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 2 |

| IgA | 34 (47.2) | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1 |

| C1q | 72 (100.0) | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 3 |

| C3 | 60 (83.3) | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 2 |

| C4 | 25 (34.7) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1 |

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy findings are shown in Table 3. Amorphous electron-dense deposits were demonstrated in 48 (90.6%) of 53 cases and were mesangial in 34 (Figure 1, B and D) and mesangial and capillary wall in 14. Extensive (≥50%) or segmental (<50%) podocyte foot process effacement and cytoskeleton condensation occurred significantly more frequently in patients with nephrotic syndrome or nephrotic-range proteinuria than in those with non-nephrotic proteinuria: Foot process effacement in 26 of 28 versus five of 22 (P = 0.0005) and cytoskeleton condensation in 24 of 28 versus seven of 22 (P = 0.0005). In the nephrotic syndrome groups of no lesions and FSGS (n = 23), 13 patients had been receiving corticosteroids for 23 d to 10 mo at the time of renal biopsy, and they had a significantly less extensive foot process effacement (P = 0.055; Table 4). Podocyte foot process effacement in this group did not correlate with glomerular capillary wall deposits, which were sparse and segmental in four of 23 (P = 0.315). In contrast, in the proliferative glomerulonephritis group (n = 17), extensive or segmental foot process effacement was expressed only in patients with capillary wall immune deposits demonstrated by electron and/or immunofluorescence microscopy (nine of 12 versus zero of five; P = 0.005). Diffuse thinning of glomerular basement membrane (<200 nm) was observed in three patients. Six patients in various histologic groups had tubuloreticular cytoplasmic inclusions in glomerular and peritubular capillary endothelial cells.

Table 3.

Electron microscopy features in relation to histologic diagnosis in 53 patients with C1q nephropathya

| Electron Microscopy Features | Light Microscopy Findings (n [%])

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Lesions (n = 5) | No Lesions (with NS) (n = 16) | FSGS (with NS) (n = 7) | Proliferative GN (n = 17) | Other (n = 8) | |

| Mesangial deposits | 4 (80.0) | 14 (87.5) | 3 (42.9) | 6 (35.3) | 7 (87.5) |

| Mesangial-SED deposits | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mesangial-SED-SEP deposits | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mesangial-SEP deposits | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Podocyte foot process effacementb | |||||

| ≥50% | 0 (0.0) | 7 (43.7) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| <50% | 0 (0.0) | 7 (43.7) | 2 (28.6) | 7 (41.2) | 1 (14.3) |

| Podocyte cytoskeleton condensation | 0 (0.0) | 15 (93.8) | 6 (85.7) | 10 (58.8) | 0 (0.0) |

SED, subendothelial; SEP, subepithelial.

Determined by estimation based on examination of the ultrastructure of nonsclerotic glomerular capillaries.

Table 4.

Degree of podocyte foot process effacement in 23 C1q nephropathy patients with NS and no lesions or FSGS by light microscopya

| Parameter | Podocyte Foot Process Effacement (n [%])

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extensive (≥50%) (n = 12) | Segmental (<50%) (n = 9) | Absent (n = 2) | ||

| Mesangial ID | 11 (91.7) | 7 (77.8) | 1 | |

| Mesangial-capillary wall ID | 1 (8.3) | 2 (22.2) | 1 | 0.315 |

| No therapy at renal biopsy | 8 (66.7) | 2 (22.2) | 0 | |

| Therapy at renal biopsyb | 4 (33.3) | 7 (77.8) | 2 | 0.055 |

ID, immune deposits.

Thirteen patients had been receiving corticosteroids for 23 d to 10 mo at the time of renal biopsy.

Follow-up

Ten follow-up biopsies were available for nine patients (Table 5), performed 6 mo to 16 yr (mean 3.9 ± 2.1) after the initial biopsy. C1q was negative in the first biopsy and positive in the repeat biopsy for three patients with nephrotic syndrome, who initially received a diagnosis of minimal-change nephropathy, and for one with acute renal failure and tubulointerstitial nephritis. For one patient with nephrotic syndrome and minimal change–like C1q nephropathy, C1q was positive in the initial biopsy and became negative in the repeat biopsy.

Table 5.

Biopsy follow-up: Histologic and immunofluorescence findings in nine patients with C1q nephropathya

| Patient | Clinical Presentation | First Renal Biopsy

|

Second/Third Renal Biopsy

|

Follow-up (yr) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Microscopy | Immunofluorescence Microscopy | Light Microscopy | Immunofluorescence Microscopy | |||

| 1 | NS | No lesions | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3 | No lesions | IgG, IgM, C1q, C3 | 0.5 |

| 2 | NS | No lesions | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q | No lesions | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q | 0.5 |

| 3 | NS | No lesions | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3 | FSGS | IgM, C1q, C3 | 0.5 |

| 4 | NS | FSGS | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3, C4 | FSGS | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3, C4 | 1.0 |

| 5 | NS | No lesions | IgM, C1q, C3 | Mild mes prol | IgG, IgM, IgA, C3 | 1.0 |

| 6 | NS | No lesions | IgM, IgA, C3 | No lesions | IgM, IgA, C1q, C3 | 2.0 |

| 7 | NS | No lesions | IgM, C3 | Mild mes prol | IgG, IgM, IgA, C1q, C3, C4 | 16.0 |

| 8 | NS | No lesions | IgM, C3 | No lesions | IgG, IgM, C1q, C3 | 13.0 |

| 9 | ARF | Tu-int nephr | IgM, IgA, C3 | Tu-int nephr | IgM, IgA, C1q, C3 | 0.5 |

ARF, acute renal failure; Tu-int nephr, tubulointerstitial nephritis; Mild mes prol, mild mesangial proliferation.

Clinical follow-up was available for 53 patients, for 4 mo to 21 yr (mean 5.4 ± 5.1). Clinical outcomes in relation to histology are shown in Table 6. A kidney donor with no light microscopy lesions retained normal kidney function after 15 yr. Among five patients with asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria and no light microscopy lesions, one had complete remission, one had partial remission, and three had stable renal disease after 6 mo to 7.5 yr without treatment. All 13 patients with nephrotic syndrome and minimal change–like lesion and eight of nine with nephrotic syndrome and FSGS received corticosteroids (10 received sequential therapy with cyclophosphamide including one who also received cyclosporine, one cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil, and one azathioprine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil; one received sequential therapy with mycophenolate mofetil; and one with cyclosporine). The majority (76.9%) of the minimal change–like group but only one third (33.3%) of the FSGS group were in complete remission after 4 mo to 21 yr, and four patients had partial remission after 4 mo to 3 yr. One patient with FSGS had resistant nephrotic syndrome despite 3 yr of combined immunosuppressive therapy, and three (33.3%) had end-stage renal disease (ESRD) 2.5, 4.0, and 9.0 yr after biopsy. Among 14 patients with proliferative glomerulonephritis, only four received immunosuppressive therapy. Two were treated with cyclophosphamide and had complete remission after 1.5 and 4.0 yr. One patient received corticosteroids and had stable renal disease after 3.0 yr. One patient, treated with corticosteroids and azathioprine, had stable renal disease after 2.0 yr. Among 10 untreated patients, six had stable renal disease after 0.5 to 6.5 yr, two had progressive renal disease after 12.0 yr, and two had ESRD after 5.5 and 7.0 yr. In the group of C1q nephropathy associated with other histologic diagnoses (n = 11), only two patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis received corticosteroids; one had partial remission after 5.5 yr, and the other had progressive renal disease during the half-year follow-up. Among untreated patients, one with tubulointerstitial nephritis had progressive renal disease after 14 yr; two with cystic renal disease and one with tubulointerstitial nephritis had ESRD after 3.0 to 5.5 yr; and five with Hantavirus nephropathy, nephrosclerosis, and thin basement membrane nephropathy had partial remission or stable renal disease 2.0 to 14.0 yr after biopsy.

Table 6.

Clinical outcomes in relation to histologic diagnosis in 53 patients with C1q nephropathy

| Clinical Outcomes | Light Microscopy Findings

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Lesions (n = 6) | No Lesions (with NS) (n = 13) | FSGS (with NS) (n = 9) | Proliferative GN (n = 14) | Other (n = 11)a | |

| Follow-up (yr; range) | 0.5 to 15.0 | 0.3 to 21.0 | 1.0 to 9.0 | 0.5 to 12.0 | 0.5 to 14.0 |

| Follow-up (yr; mean ± SD) | 5.4 ± 6.0 | 7.1 ± 7.4 | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 4.9 ± 3.5 | 6.5 ± 4.7 |

| Normal/complete remission (n [%]) | 2 (33.3) | 10 (76.9) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Partial remission (n [%]) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Treatment resistant NS (n [%]) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stable renal disease (n [%]) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (36.4) |

| Progression of renal disease (n [%]) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (18.2) |

| ESRD (n [%]) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (27.2) |

Tubulointerstitial nephritis (n = 2), Hantavirus nephropathy (n = 1), benign hypertensive nephrosclerosis (n = 2), thin basement membrane nephropathy (n = 2), autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (n = 1), and medullary cystic disease (n = 1).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of C1q nephropathy differs in various articles, ranging from 0.2 to 2.5% in biopsies from children and adults,1,3,7 to 2.1 and 6% in pediatric biopsies,8,10 to 16.5% among renal biopsies of children with nephrotic syndrome and persistent proteinuria.4 We found a 1.9% prevalence in this study of consecutive kidney biopsies obtained from patients of all ages and 9.2% among pediatric renal biopsies in our previous study.6 We believe that the differences in prevalence result from the different indications for renal biopsy and the differences in the age of patients in various studies. Black patients constituted 82% in the series reported by Jennette and Falk and 74% in the series of Markowitz et al.3,7 The exclusive occurrence in white patients in our study corresponds to the racial composition of our referral population.

C1q nephropathy was originally described as a distinct clinicopathologic entity by Jennette and Hipp1 in 1985, usually causing steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in older children and young adults. The defining feature was intense dominant or co-dominant staining for C1q in patients without evidence of SLE. More recent modified criteria require ≥2+ (on a scale of 0 to 4+) immunostaining for C1q with a predominantly mesangial distribution, frequently accompanied by IgG and IgM, which may be less intense, equally intense, or more intense, in patients without evidence of SLE.7 In addition, type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, which frequently has intense C1q staining, is an exclusion criterion.1,2,7

Our cohort of 72 patients had dominant or co-dominant C1q associated with Ig and other complement components in glomerular deposits. In 30.6%, a “full house” pattern, which is often observed in lupus nephritis,11 was demonstrated significantly more frequently in patients with proliferative glomerulonephritis; however, none of our patients showed any feature of SLE at the time of biopsy or after a mean 5.4-yr follow-up, including six with endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions and two with extraglomerular small vessel vasculitis. Similarly to our results, Sharman et al.12 described nine patients who had C1q nephropathy and for whom a diagnosis of “seronegative lupus nephritis” had initially been considered. None of these patients developed SLE during a mean follow-up of 5.1 yr.

The majority of studies have reported electron-dense deposits in all renal biopsy samples of C1q nephropathy.1,3,8,12 In our study, deposits were demonstrated in 90.6% of cases. We believe that occasional segmental distribution of immune deposits in C1q nephropathy may be the reason that they are not sampled for electron microscopy in some biopsies.

The histologic patterns of C1q nephropathy range from no glomerular lesions to FSGS to proliferative glomerulonephritis. Minimal change–like lesion and FSGS with nephrotic syndrome predominated, comprising 38.9% of cases in our large series, similar to other reported studies.3,4,8 These patients were significantly younger than those who had no lesions or proliferative glomerulonephritis by light microscopy and presented with chronic kidney disease or asymptomatic urine abnormalities. Furthermore, our study demonstrated that podocytopathy, expressed as extensive or segmental podocyte foot process effacement and cytoskeleton condensation, was not associated with glomerular capillary wall immune deposits in patients with nephrotic syndrome, whereas in the group of proliferative glomerulonephritis, this lesion of podocytes was expressed only in patients with capillary wall immune deposits. This difference may be due to different pathogenic mechanisms in the two clinicopathologic subsets of C1q nephropathy. Markowitz et al.3 suggested that C1q nephropathy was within the spectrum of minimal-change nephropathy and FSGS. They assumed that C1q could bind to Ig that become trapped nonspecifically in the mesangium as a result of increased mesangial trafficking in the setting of glomerular proteinuria. We are more inclined to the opinion that glomerular deposits of immune reactants reflect immune complex deposition, which may influence the course and prognosis of podocytopathies manifesting as minimal change–like lesion or FSGS with C1q nephropathy; however, the pathogenesis of C1q nephropathy in relation to podocyte injury remains uncertain.13,14

One third of our patients had proliferative glomerulonephritis with or without glomerular sclerosis and extracapillary crescents. Their clinical presentation was chronic kidney disease or asymptomatic hematuria and/or proteinuria. Proliferative glomerulonephritis has been found with various frequencies in the reported C1q nephropathy series, as well as in a few case reports.1,4,7,8,12,15,16 This form of C1q nephropathy has characteristic features of immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis and may share similarities with IgA nephropathy.8 A patient can in fact fulfill the diagnostic criteria for both conditions. The diagnosis of C1q nephropathy requires ≥2+ immunofluorescence staining for C1q, and IgA nephropathy requires IgA to be dominant or co-dominant Ig.7,17 The overlapping of the two diagnoses can be avoided by requiring that IgA nephropathy have more staining for C3 than C1q.17 Furthermore, rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis with immunofluorescence features of C1q nephropathy was reported in a 3-yr-old boy who progressed to ESRD within 14 wk despite immunosuppressive treatment.5 Some authors have included membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in the category of C1q nephropathy, although Jennette and co-workers1,7,16,18 recommended that this form of glomerulonephritis be an exclusion criterion for C1q nephropathy.

Our study demonstrated that characteristic immunofluorescence appearance of C1q nephropathy can rarely be encountered in clinically healthy people. We found it in two kidney donors with normal urine examinations. Furthermore, immune deposits comprising C1q were found in our study in 19.4% of patients with clinically and histopathologically proven hypertensive nephrosclerosis, tubulointerstitial nephritis, Hantavirus nephropathy, cystic renal disease, and thin basement membrane nephropathy, probably as an unrelated concomitant condition. It is unclear whether the kidney donors and patients with incidentally detected C1q deposits have a mild form of C1q nephropathy or merely immune deposits of uncertain significance and pathogenesis. This is similar to IgA deposits occurring as an incidental finding in kidneys from healthy transplant donors.

Our biopsy follow-up study showed that patients with nephrotic syndrome and minimal change–like C1q nephropathy had the same histologic picture in repeat biopsies, except for one patient who developed FSGS. Glomerular immune deposits comprising C1q may diminish or even disappear in treated patients. Conversely, a patient with nephrotic syndrome and apparent minimal-change nephropathy without C1q deposits in an initial biopsy may be found to have C1q deposits consistent with C1q nephropathy in a repeat biopsy. These findings suggest that immune complex deposition is not a basic pathogenic mechanism in the C1q nephropathy subset with characteristics of podocytopathy but might influence the course of the disease. Similar to our results, Fukuma et al.9 demonstrated the disappearance of C1q deposits in repeat kidney biopsies in two of four treated children with minimal change–like C1q nephropathy. Nishida et al.16 reported persistence of immune deposits in a patient with C1q nephropathy, associated with mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, despite clinical and histologic improvement after 5 yr.

Our cohort of patients with C1q nephropathy and with clinicopathologic follow-up data is the largest yet reported. This cohort confirmed diverse clinical presentations and outcomes. All patients but one presenting with nephrotic syndrome received immunosuppressive treatment, and patients with minimal change–like lesion showed a significantly more favorable outcome than those with FSGS. In the FSGS group, one third progressed to ESRD during mean 2.9 yr of follow-up. This is comparable to the recently published study of 179 patients with different variants of idiopathic FSGS, reporting the overall cohort survival of 67% at 3 yr.19 Among our patients with proliferative glomerulonephritis, only 20% were treated with immunosuppressive drugs. There was no significant difference in outcome between treated and untreated patients, although two patients with ESRD at follow-up were among those who were not treated. The majority had stable renal disease after follow-up. Our results are in line with the reported studies, showing that the outcome of patients with C1q nephropathy and with nephrotic syndrome and FSGS was generally poor, whereas patients with no glomerular abnormalities and those not presenting with nephrotic syndrome preserved stable renal function despite the absence of treatment.3,4,8 Fukuma et al.9 in their study of C1q nephropathy found no significant differences in histologic findings and clinical outcomes among 18 children presenting with asymptomatic urinary abnormalities and 12 children presenting with nephrotic syndrome. The prognosis was good for most of them during follow-up of 3 to 15 yr. Only two patients with FSGS progressed to ESRD.

In conclusion, a diagnosis of C1q nephropathy is based on the immunohistologic finding of intense, mostly mesangial staining for C1q in patients without evidence of SLE or membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Histologic findings, clinical presentations, and, presumably, pathogenic events are heterogeneous. There are two main clinicopathologic subsets: One of podocytopathy with features of minimal change–like lesion or FSGS, presenting with nephrotic syndrome, frequently relapsing, and the other varying from no glomerular lesions to diverse forms of proliferative glomerulonephritis, with typical features of immune complex–mediated glomerular disease, presenting mostly with chronic kidney disease or asymptomatic urine abnormalities. Clinical outcomes are diverse. Patients with nephrotic syndrome and C1q nephropathy, particularly those with FSGS, often show a poor response to corticosteroid treatment. Patients with minimal change–like lesion or proliferative glomerulonephritis have a better prognosis with better preservation of renal function.

CONCISE METHODS

A review of native kidney biopsies (n = 4048) examined from 1985 through 2005 at the Institute of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana, identified C1q nephropathy in 77 (1.9%) biopsies obtained from 72 patients. C1q nephropathy was defined as ≥2+ (on a scale of 0 to 4+) dominant or co-dominant immunostaining for C1q, with a predominantly mesangial distribution, in patients without clinical or serologic evidence of SLE.1 A further exclusion criterion was type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

All biopsies were processed for light and immunofluorescence microscopy and 53 for electron microscopy according to standard techniques. For light microscopy, renal tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, periodic acid-Schiff, periodic acid silver methenamine/Azan, and van Gieson-Weigert stains. For immunofluorescence microscopy, kidney samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and cryostat sections were stained with FITC-labeled antisera to human IgA, IgG, IgM, κ and λ light chains, C3, C1q, C4, fibrin/fibrinogen, and albumin (Dakopatts, Copenhagen, Denmark). Tissue for electron microscopy was fixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide and embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Biopsy follow-up was available for nine patients, with 10 rebiopsies. For this study, all histopathology findings were reviewed by the senior pathologist (D.F.), who was blinded to the scores of other observers as well as to the scores of his initial examinations.

Medical records were reviewed retrospectively for the following findings at renal biopsy: Urinalysis; serum creatinine; albumin; cholesterol; C3, C4, and CH50; serum antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies; 24-h urinary protein excretion; BP; and serology for hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and HIV. All patients had negative ANA and anti-DNA antibodies, and all had normal serum complement. Data about HBV, HCV, and HIV serology were available for 57 of 72 patients. Two patients had positive anti–hepatitis B surface antibodies, and no patient had positive serology for HCV or HIV. In the medical history, other underlying conditions were pharyngitis or tonsillitis (n = 17), bronchopneumonia (n = 4), diarrhea (n = 2), erysipelas (n = 1), meningitis (n = 1), meningoencephalitis (n = 1), encephalitis (n = 1), rheumatic fever (n = 1), and autoimmune hepatitis (n = 1).

For adults, the following definitions were used: Hematuria, more than 5 red blood cells per high-power field; nephrotic-range proteinuria, urinary protein excretion >3.0 g/d; hypoalbuminemia, albumin <32 g/L; hyperlipidemia, serum cholesterol >5.7 mmol/L; nephrotic syndrome, nephrotic-range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and edema; renal insufficiency, estimated GFR from serum creatinine, gender, age, and race (MDRD4v equation) <90 ml/min; acute renal failure, abrupt decline in renal function over a period of days; chronic kidney disease, presence of persistent proteinuria and/or hematuria (>3 mo) and impaired renal function as defined by estimated GFR <90 ml/min; and hypertension, systolic BP >140 mmHg or diastolic BP >90 mmHg. The definitions used for children were as follows: Nephrotic range proteinuria, urinary protein excretion >40 mg/m2 per h; hypoalbuminemia, serum albumin <25 g/L; hyperlipidemia, lipids >95th percentile for patient age and gender; hypertension, systolic or diastolic BP >95th percentile on the basis of gender, age, and height percentile; and renal insufficiency, estimated GFR from serum creatinine, the child's height, and a constant, considering age and gender (Schwartz formula) <90 ml/min. For outcome analysis, complete remission was defined as stable renal function and proteinuria <0.25 g/d for adults and <4 mg/m2 per h for children. Partial remission was defined as reduction in proteinuria by at least 50% and stable renal function. Progression of renal disease was defined as elevation of serum creatinine by at least 20%.

Statistical Analyses

In statistical analysis, continuous variables were compared using the Student independent samples t test, and categorical variables were compared using Pearson χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Branka Grmek, Metka Janc, and Nataša ŠtokPfajfer as well as Žiga Kušar, BSc, for technical assistance. We also thank Prof. Dr. Tomaž Rott, MD, for cooperating in the histopathologic microscopy examinations of renal biopsies.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jennette JC, Hipp CG: C1q nephropathy: A distinct pathologic entity usually causing nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 6: 103–110, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennette JC, Hipp CG: Immunohistopathologic evaluation of C1q in 800 renal biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol 83: 415–420, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz GS, Schwimmer JA, Stokes MB, Nasr S, Seigle RL, Valeri AM, D'Agati VD: C1q nephropathy: A variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 64: 1232–1240, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iskandar SS, Browning MC, Lorentz WB: C1q nephropathy: A pediatric clinicopathologic study. Am J Kidney Dis 18: 459–465, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava T, Chadba V, Taboada EM, Alon US: C1q nephropathy presenting as rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol 14: 976–979, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kersnik Levart T, Kenda RB, Avguštin Čavić M, Ferluga D, Hvala A, Vizjak A: C1q nephropathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol 20: 1756–1761, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennette JC, Falk RJ: C1q nephropathy. In: Textbook of Nephrology, 4th Ed., edited by Massry SG, Glassock R, Philadelphia, Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins, 2000, pp 730–733

- 8.Lau KK, Gaber LW, Delos NM: C1q nephropathy: Features at presentation and outcome. Pediatr Nephrol 20: 744–749, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuma Y, Hisano S, Segawa Y, Niimi K, Tsuru N, Kaku Y, Hatae K, Kiyoshi Y, Mitsudome A, Iwasaki H: Clinicopathologic correlation of C1q nephropathy in children. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 412–418, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida M, Kawakatsu H, Okumura Y, Hamaoka K: C1q nephropathy with asymptomatic urine abnormalities. Pediatr Nephrol 20: 1669–1670, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones E, Magil A: Nonsystemic mesangiopathic glomerulonephritis with “full house” immunofluorescence. Am J Clin Pathol 78: 29–34, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharman A, Furness P, Feehally J: Distinguishing C1q nephropathy from lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1420–1426, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapell SB, Myrthil G, Fogo A: An adolescent with relapsing nephrotic syndrome: Minimal-change disease versus focal-segmental glomerulosclerosis versus C1q nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 966–970, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB: A proposed taxonomy for the podocytopathies: A reassessment of the primary nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 529–542, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imai H, Tadashi Y, Satoh K, Miura AB, Sugawara T, Nakamoto Y: Pan-nephritis (glomerulonephritis, arteriolitis, and tubulointerstitial nephritis) associated with predominant mesangial C1q deposition and hypocomplementemia: A variant type of C1q nephropathy? Am J Kidney Dis 27: 583–587, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishida M, Kawakatsu H, Komatsu H, Ishiwari K, Tamai M, Sawada T: Spontaneous improvement in a case of C1q nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 35: E22, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emancipator SN: Benign essential hematuria, IgA nephropathy, and Alport syndrome. In: Renal Biopsy Interpretation, edited by Silva FG, D'Agati VD, Nadasdy T, New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1996, pp 147–180

- 18.Davenport A, Maciver AG, Mackenzie JC: C1q nephropathy: Do C1q deposits have any prognostic significance in the nephrotic syndrome? Nephrol Dial Transplant 7: 391–396, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DB, Franceschini N, Hogan SL, ten Holder S, Jennette CE, Falk RJ, Jennette JC: Clinical and pathologic characteristics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants. Kidney Int 69: 920–926, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]