Abstract

The effects of thyroid hormone on renin secretion, renin content, and renin mRNA levels in juxtaglomerular (JG) cells harvested from rat kidneys were determined by radioimmunoassays and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Despite a lack of immediate effect, incubation with triiodothyronine dose dependently increased renin secretion during the first 6 h and elevated renin content and renin mRNA levels during the subsequent period. Simultaneous incubation with triiodothyronine and the calcium ionophore A-23187 abolished the increase in renin secretion and attenuated the increase in renin content but did not affect the increase in renin mRNA levels. During simultaneous incubation with triiodothyronine and the adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ-22536 or membrane-soluble guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP), the increases in renin secretion, content, and mRNA were similar to those observed in the presence of triiodothyronine alone, except for a cGMP-induced attenuation of the increase in renin secretion. These findings suggest that thyroid hormone stimulates renin secretion by JG cells through the calcium-dependent mechanism, whereas the stimulation of renin gene expression by thyroid hormone does not involve intracellular calcium or cyclic nucleotides.

Keywords: triiodothyronine; calcium; adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate; reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

CIRCULATING RENIN activates the renin-angiotensin system and thereby contributes to systemic hemodynamics (1) and cardiovascular hypertrophy (23). Juxtaglomerular (JG) cells are the primary sources of circulating renin in rats and humans, and in vivo renin synthesis and secretion are regulated by the chloride concentration in the macula densa, renal perfusion pressure, renal sympathetic nerve activity (8), other electrolytes (13), and various vasoactive agents (8). On the basis of the results of studies to date, cytosolic Ca2+, adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP), and guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) are not only definitive intracellular second messengers in the regulation of renin secretion (8) but also major regulatory factors in the control of renin gene expression (3-5). Intracellular Ca2+ and cGMP exert an inhibitory effect on renin secretion, and cAMP stimulates renin secretion (8). Increases in intracellular cAMP stimulate renin gene expression in mouse JG cells, and increases in intracellular Ca2+ inhibit it (4, 5). In addition, cAMP selectively increases the half-life (t‰) of renin mRNA in JG cells (3).

In vivo studies suggest that thyroid hormone may also influence renin synthesis and secretion by JG cells. Rats injected with l-thyroxine (6) and triiodothyronine (22) exhibit a hyperthyroid state accompanied by increased plasma renin activity. Increased sympathetic nerve activity has been thought to account for the increased plasma renin activity in hyperthyroidism (10); however, high sympathetic nerve activity is also observed in hypothyroidism (24). Nevertheless, thyroidectomy- (6) and methimazole-induced thyroid dysfunction (22) decreases plasma renin activity. Furthermore, our previous study demonstrated that fluctuations in plasma and renal renin levels in sympathetic-denervated rats coincided with changes in their serum thyroid hormone levels (20). These findings imply that the renin levels observed may be directly attributable to thyroid hormone without mediation by the sympathetic nervous system. However, the direct effects of thyroid hormone on JG cells have never been studied.

Most physiological effects of thyroid hormone are mediated by high-affinity nuclear receptors, although some extranuclear thyroid hormone actions have been identified (14). Studies have demonstrated that the nuclear actions of thyroid hormone can modulate intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ and cyclic nucleotides and/or their actions. Thyroid hormone influences the gene expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-adenosinetriphosphatase (ATPase) (2, 9, 27, 28) through its nuclear receptors and thus modulates intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. In addition, in a pituitary cell line transfected with the 5′-flanking DNA of the human renin gene, cAMP upregulates human renin gene expression (7), and thyroid hormone also modulates renin gene expression through influencing the levels of pituitary-specific factor-1 (Pit-1), which is supposed to be involved in cAMP regulation of renin gene expression (7, 31). Therefore, the effects of thyroid hormone on renin regulation by JG cells may depend on intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ and cyclic nucleotides.

We hypothesized that thyroid hormone stimulates renin secretion, renin content, and renin mRNA levels in JG cells and that intracellular concentrations of Ca2+, cAMP, and cGMP modulate the ability of thyroid hormone to influence renin secretion, content, and mRNA levels in JG cells. To test our hypothesis, in the present study we assessed the renin secretion rate (RSR), renin content, and renin mRNA levels by radioimmunoassay and a semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in primary cultured rat JG cells incubated with various concentrations of triiodothyronine for different periods. We also investigated the effects of the calcium ionophore A-23187, the adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ-22536, and the membrane-soluble derivative of cGMP, dibutyryl cGMP (DBcGMP), on triiodothyronine-stimulated renin secretion, content, and mRNA levels.

METHODS

Isolation and primary culture of rat JG cells

Rat JG cells were isolated according to the method described previously (12). Briefly, the kidneys of Sprague-Dawley rats (100−150 g body wt) were perfused in situ with 15 ml of buffer A (Hanks’ balanced salt solution supplemented with 1 g/l glucose, 12.11 g/l sucrose, 2.2 g/l NaHCO3, 2.6 mM l-glutamine, 0.84 g/l Na citrate, and 10 mg/l bovine serum albumin). The renal medulla was removed, and the cortex was minced into 1-mm3 pieces. The minced tissue was incubated, with gentle stirring, in buffer B (buffer A without Na citrate) supplemented with 0.25% trypsin and 0.1% collagenase-A from Clostridium histolyticum for 120 min in 5% CO2 at 37°C. The incubation mixture was then poured over a 22-μm nylon screen. Single cells that passed through the screen were collected, centrifuged at 50 g for 10 min, and washed twice in RPMI-1640 with 25 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES). To increase the percentage of viable JG cells, we centrifuged 11 × 107 cells through 35 ml of isotonic 25% (vol/vol) Percoll solution at 20,000 g for 20 min. Cells migrating to a density of 1.06 g/ml after centrifugation were used for primary culture.

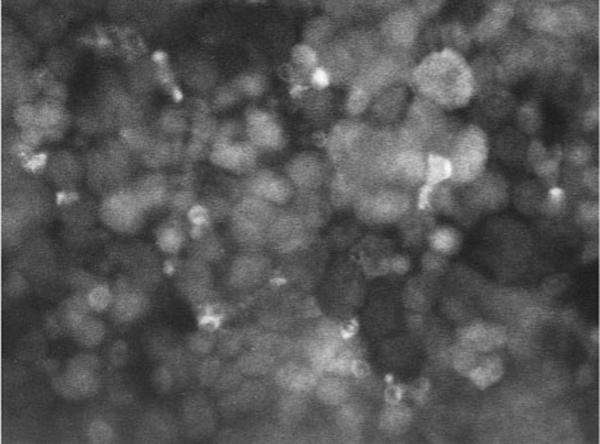

The cells were separated from Percoll by being washed twice with 60 ml of RPMI-1640 containing 25 mM HEPES. These cells were suspended at 106 cells/ml in culture medium consisting of RPMI-1640 with 25 mM HEPES, 0.3 g/l l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.66 U/l insulin from bovine serum, and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell number was determined using a Coulter counter (Miami, FL). The suspended cells were distributed in 1-ml aliquots into individual wells of 8-well chamber slides containing 1 ml of culture medium and incubated at 37°C. In some dishes, immunofluorescence staining for renin was performed after the experiment, as described by us previously (12). Briefly, the cells were washed twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in DPBS. After being rinsed in DPBS, fixed cells were incubated for 2 min in 96% ethanol at −20°C. This was followed by a 20-min incubation in 10% normal swine serum, 0.1% normal rabbit antibody, and 0.1% normal goat antibody in DPBS. After further rinsing in DPBS, the samples were incubated with rabbit antiserum against mouse renin diluted 1:400 in a solution of 10% normal swine serum, 0.1% normal rabbit antibody, and 0.1% normal goat antibody in DPBS at 4°C for 12 h. This rabbit anti-mouse serum had a 99% cross-reactivity against rat renin. Five-minute DPBS rinses were performed six times, followed by a 45-min incubation with immunofluorescence-F(ab′)2-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G. The samples were rinsed subsequently for 30 min and mounted on glycerol containing 10% DPBS and 10 mg of phenylenediamine (pH 7.4) for fluorescence microscopy. The specificity of the immune reaction was tested with routine procedures. The samples were examined under a photomicroscope, and, as shown in Fig 1, we confirmed that 89 ± 3% of the cells (n = 5 primary cultures) were positive for renin at 72 h after isolation. Trypan blue exclusion staining indicated a cell viability of 96 ± 1% in freshly isolated cells of eight cultures. At the beginning and end (36 h) of experiments, the cell viabilities of untreated cells averaged 92 ± 1 and 90 ± 1% (n = 5 cultures), respectively, and the viability of cells treated with 1,000 pM triiodothyronine averaged 91 ± 1 and 87 ± 2% (n = 5 cultures), respectively. There was no significant difference in the cell viability among these four groups. The cell viability slightly but significantly correlated with the incubation period (r = −0.477, n = 20, P = 0.032) but did not correlate with triiodothyronine concentration (r = −0.246, n = 20, P = 0.301).

Fig. 1.

Renin immunofluorescence in a representative primary culture of juxtaglomerular (JG) cells incubated for 72 h after isolation; magnification, ×400.

Application of triiodothyronine to JG cells

Thirty-six hours after primary culture, the culture medium was replaced with control culture medium or culture medium containing 1, 10, 100, or 1,000 pM of triiodothyronine. All triiodothyronine-containing culture mediums were prepared by diluting 1,000 pM triiodothyronine-containing culture medium with control culture medium, and the pH (7.2) of 1,000 pM triiodothyronine-containing culture medium was similar to that measured in the control culture medium. Because preliminary studies have shown that triiodothyronine has a t‰ of 36.3 h (n = 6 cultures) in culture medium, medium changes were performed every 12 h to ensure stable hormone concentrations.

Measurement of RSR

Spontaneous RSR was measured at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 h after the first exchange of culture medium. After the culture medium was withdrawn, the cells were washed twice with prewarmed buffer C (132 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM sodium acetate, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2). The culture dishes were filled with 2 ml of buffer C, and 30-μl samples of the cell-conditioned buffer were removed and centrifuged immediately before and 10, 20, and 30 min after replacement of the buffer. The supernatants were stored at −80°C until renin activity was assayed, and RSR was calculated from the linear increase in renin activity in the samples. Immediately after RSR measurement, the cells and residual buffer were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for assay of renin content or renin mRNA. The stored cells were divided into two assay groups, one for measurement of JG cell renin content and the other for renin mRNA analysis.

Measurement of the renin content of JG cells

Frozen cells were homogenized in 1 ml of buffer (pH 6.0) containing 2.6 mM EDTA, 1.6 mM dimercaprol, 3.4 mM 8-hydroxyquinoline sulfate, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 5 mM ammonium acetate with a polytron (Kinematica, Littau, Switzerland). The homogenates were centrifuged at 5,000 revolutions/min for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was removed. An aliquot of the supernatant was diluted 1:10 for the assay of renin activity. The renin content of the JG cells was calculated as renin activity of the supernatant obtained per million cells.

Assay of renin activity

Using a renin substrate composed of plasma from bilaterally nephrectomized male Sprague-Dawley rats, we incubated samples for 1 h at 37°C. The reaction was carried out in 0.2 M sodium malate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 5 mM PMSF, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% gentamycin. Renin activity was determined by the generation of angiotensin I (ANG I) from a plasma angiotensinogen substrate. The levels of ANG I were measured with a radioimmunoassay coated-bead kit from Dinabott Radioisotope Institute (Tokyo, Japan). In the present study, renin activity assay was performed to avoid the possible conversion of inactive prorenin to active renin, and all samples were frozen to avoid the cryoactivation of prorenin. Frozen samples were thawed rapidly to room temperature, and the homogenates of frozen cells were centrifuged at pH 6.0, at which pH cryoactivation of prorenin does not occur (29). The reaction of renin activity assay was also carried out at pH 6.0.

Renin mRNA analysis

Total RNA from frozen cells was extracted with the use of the Total RNA Separator Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Extracted RNA was suspended in ribonuclease-free water and quantified by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. In preliminary investigations, the integrity of the purified RNA was confirmed by identification of the 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA bands separated by electrophoresis of the RNA sample through a 1% (wt/vol) agarose-formaldehyde gel.

Total RNA from the cells was reverse transcribed using the GeneAmp RNA PCR Core Kit (PerkinElmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT), as described previously (20). Each sample contained 0.5 μg of total RNA, 100 nmol of MgCl2, 1,000 nmol of KCl, 200 nmol of tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris)·HCl (pH 8.3), 20 nmol of each dNTP (dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP), 20 units of ribonuclease inhibitor, 50 pmol of random hexamers, and 50 units of murine leukemia virus RT in a final volume of 20 μl. After incubation at 42°C for 15 min, the samples were heated for 5 min at 99°C to terminate the reaction and were then stored at 5°C until assayed.

The primers for renin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were identical to those used in our in vivo study (20). The sequences of the renin primers were 5′-TGCCACCTTGTTGTGTGAGG-3′ (sense), which corresponded to bases 851−870 (from exon 7) of the cloned full-length sequence, and 5′-ACCCGATGCGATTGTTATGCCG-3′ (antisense), which annealed to bases 1,203−1,224 (from exon 9). GAPDH was used as an internal standard, and the sequences of the GAPDH primers were 5′-TCCCTCAAGATTGTCAGCAA-3′ (sense), which corresponded to bases 492−511 of the cloned full-length sequence, and 5′-AGATCCACAACGGATACATT-3′ (antisense), which annealed to bases 780−799. The predicted sizes of the amplified renin and GAPDH cDNA products were 374 and 308 base pairs (bp), respectively. The sense primers in each reaction were radiolabeled with the use of [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and phage T4 polynucleotide kinase, according to the instructions in the Kination Kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan).

A 5-μl sample of RT mixture was used for amplification, and 25 nmol of MgCl2, 1,000 nmol of KCl, 200 nmol of Tris·HCl (pH 8.3), 3.75 pmol of each antisense primer, 3.75 pmol and 106 counts/min of each sense primer, and 0.625 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase were added to each sample according to the instructions in the GeneAmp RNA PCR Core Kit. To minimize nonspecific amplification, we used a “hot start” procedure in which PCR samples were placed in a thermocycler (PerkinElmer Cetus) prewarmed to 94°C. After 120 s, PCR was performed for 25 cycles using a 30-s denaturation step at 94°C, a 60-s annealing step at 62°C, and a 75-s extension step at 72°C. We added a 300-s extension step at 72°C. After completion of RT-PCR, DNA was electrophoresed through an 8% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. Gels were dried on filter paper, exposed to a BAS 2000 imaging plate (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan) for 1 min, and quantified with a BAS 2000 Laser Image Analyzer (Fuji Film). RT yielded two clear bands that had the predicted sizes of 374 bp for renin and 308 bp for GAPDH. These bands were not observed when the PCR procedure was performed without RT, and no other bands were noted. This indicated that the 374- and 308-bp bands originated in mRNA, not genomic DNA. Renin mRNA levels were assessed as renin-to-GAPDH ratios.

Contribution of A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP to triiodothyronine-modulated renin regulation by JG cells

Additional experiments were performed to investigate the contribution of Ca2+, cAMP, and cGMP to the thyroid hormone-induced changes in renin secretion, renin content, and renin mRNA levels. To increase the intracellular Ca2+ and cGMP levels, JG cells were incubated with the calcium ionophore A-23187 (1 μM) and the membrane-soluble derivative of cGMP, DBcGMP (100 μM). In addition, to decrease the intracellular cAMP level, JG cells were incubated with the adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ-22536 (100 μM). The effect of A-23187, DBcGMP, and SQ-22536 on RSR, renin content, and renin mRNA levels was determined in control cells and cells treated with triiodothyronine at the concentration and for the period that yielded the maximum response of renin secretion or renin content and mRNA. Medium changes were performed every 12 h. The stability of the bioactivity of A-23187, DBcGMP, and SQ-22536 during the 12-h incubation period was checked by the following procedure. JG cells were incubated in culture medium containing these agents for 12 h; then the medium was collected and applied to naive JG cells. The percent change in RSR caused by these agents in the 12-h-incubated mediums was measured and compared with the percent change in RSR induced by fresh medium containing these agents. A-23187 in the fresh medium and the 12-h-incubated medium decreased RSR by 65.6 ± 3.2 and 61.1 ± 4.1%, respectively (n = 3 cultures in both). Similarly, SQ-22536 in the fresh medium and the 12-h-incubated medium decreased RSR by 66.1 ± 3.6 and 61.5 ± 4.4% (n = 3 cultures in both), and DBcGMP in the fresh and 12-h-incubated mediums decreased RSR by 58.5 ± 5.3 and 50.6 ± 6.2% (n = 3 cultures in both). No significant differences were observed between the responses to the fresh and 12-h-incubated mediums.

Trypsin, bovine serum insulin, immunofluorescence-F(ab′)2-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G, triiodothyronine (3,5,3′-triiodo-l-thyronine), and DBcGMP were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Collagenase-A was obtained from Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany). RPMI-1640 with 25 mM HEPES was supplied by Whittaker Bioproducts (Walkersville, MD). Streptomycin and penicillin were purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). Fetal bovine serum was from Hyclone Laboratories (Logan, UT). A-23187 was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). SQ-22536 was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by the paired and unpaired t-test. Differences between treatments were assessed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Scheffeé's S-test and Dunnett's t-test for repeated measures in the dose- and time-dependent studies and by one-way ANOVA with Scheffeé's F-test in studies using A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP. Statistical significance is defined as P < 0.05, and the results are shown as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Effect of triiodothyronine on renin secretion by JG cells

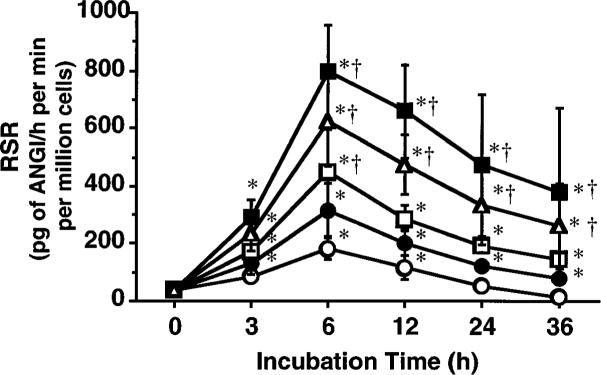

The RSR data at 0 h after incubation with triiodothyronine were not different from the data at 0 h in the absence of triiodothyronine (38 ± 12 pg of ANG I·h−1·min−1·million cells−1). As illustrated in Fig. 2, RSR in the untreated cells showed a slight but significant increase up to 6 h after the initiation of incubation and decreased thereafter. These changes in RSR were significantly enhanced by triiodothyronine in a dose-dependent manner. The maximum RSR averaged 798 ± 162 pg of ANG I·h−1·min−1·million cells−1 and occurred at approximately the 6-h incubation point with 100 pM of triiodothyronine. However, at all incubation periods, RSR in the cells treated with 1,000 pM was not significantly different from that observed in the cells treated with 100 pM.

Fig. 2.

Effects of 0 (○), 1 (•), 10 (□), 100 (■), and 1,000 pM (△) triiodothyronine on renin secretion rate (RSR) of primary cultures of JG cells prepared from rat kidneys. ANG I, angiotensin I. Each value was calculated from data obtained in 5 primary cultures. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 h value. †P < 0.05 vs. 0 pM value.

Effect of triiodothyronine on the renin content of JG cells

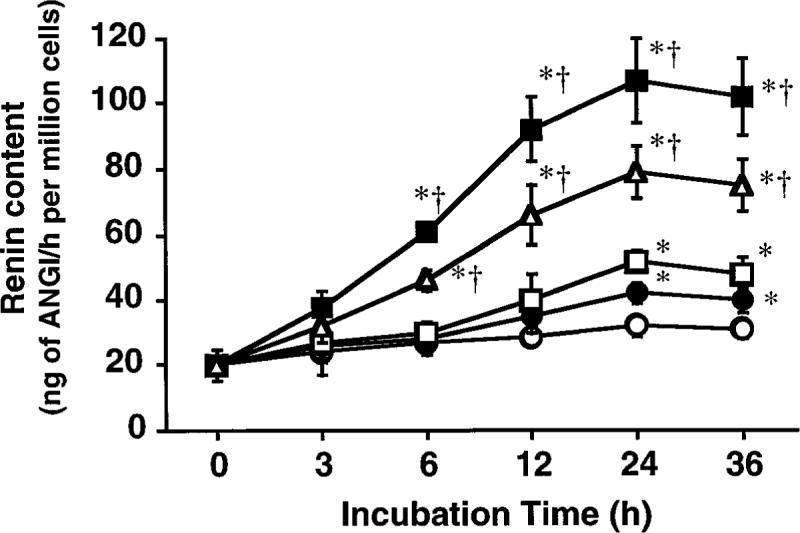

The renin content of JG cells was increased significantly by triiodothyronine treatment in a dose- and incubation period-dependent manner, as depicted in Fig. 3. The greatest increase in renin content of JG cells was observed after 24 h of incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine and averaged 107 ± 13 ng of ANG I·h−1·min−1·million cells−1. However, no significant difference in renin content was observed between 24 and 36 h at any concentration of triiodothyronine or between 100 and 1,000 pM at any incubation period.

Fig. 3.

Effects of 0 (○), 1 (•), 10 (□), 100 (■), and 1,000 pM (△) triiodothyronine on renin content of primary cultures of JG cells harvested from rat kidneys. Each value was calculated from data obtained in 5 primary cultures. * P < 0.05 vs. 0 h value. †P < 0.05 vs. 0 pM value.

Effect of triiodothyronine on renin mRNA in JG cells

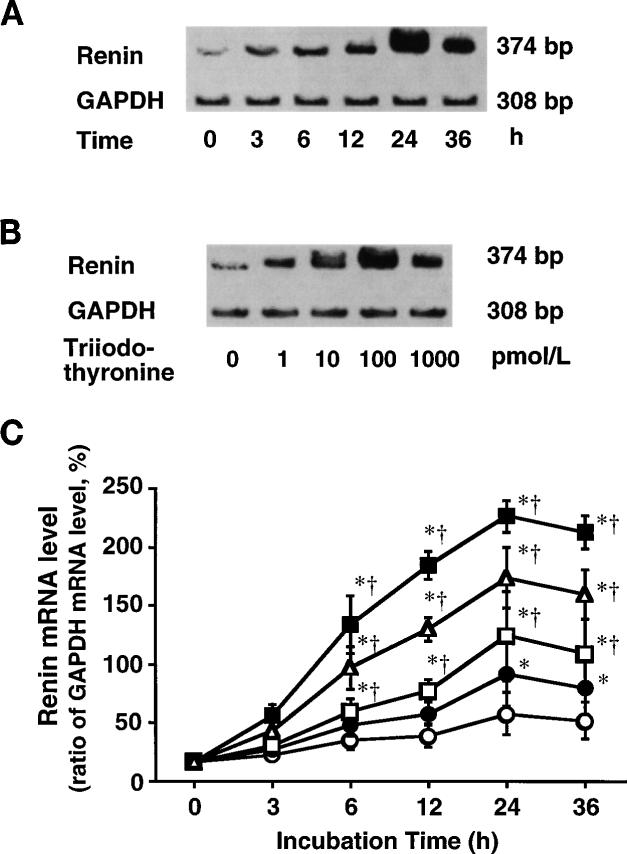

Although GAPDH mRNA levels were not influenced by triiodothyronine, triiodothyronine dose and time dependently increased renin mRNA levels, as demonstrated in Fig. 4, A and B. The greatest enhancement of renin mRNA expression occurred by 24 h of incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine [226 ± 14%; P < 0.05 compared with the other doses and incubation periods (Fig. 4C)]. However, at any concentration of triiodothyronine, renin mRNA levels at 36 h were not significantly different from those observed at 24 h. At any incubation period, renin mRNA levels at 1,000 pM did not significantly differ from those observed at 100 pM.

Fig. 4.

A: representative electrophoretogram showing incubation period-dependent effect of 100 pM triiodothyronine on renin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels of JG cells; bp, base pair. B: representative electrophoretogram showing concentration-dependent effect of 24-h incubation with triiodothyronine on renin and GAPDH mRNA levels of JG cells. C: effects of 0 (○),1(•), 10 (□), 100 (■), and 1,000 pM (△) triiodothyronine on renin mRNA level (ratio of GAPDH mRNA level, %) in primary cultures of JG cells harvested from rat kidneys. Each value was calculated from data obtained in 5 cultures. * P < 0.05 vs. 0 h value. †P < 0.05 vs. 0 pM value.

Effects of A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP on triiodothyronine stimulation of renin secretion

The experiments summarized in Table 1 were performed to investigate the contribution of intracellular Ca2+, cAMP, and cGMP to the triiodothyronine-induced stimulation of renin secretion at 6 h. A 6-h incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine significantly increased RSR by 341 ± 3%. The chronic increase in intracellular Ca2+ caused by 6-h treatment with the calcium ionophore A-23187 significantly reduced basal RSR, as shown in Table 1, and completely inhibited the increase in RSR in response to triiodothyronine. Chronic inhibition of cAMP synthesis with SQ-22536 significantly reduced the basal RSR compared with that measured in untreated cells (Table 1). Incubation with both 100 pM triiodothyronine and SQ-22536 significantly increased RSR by 336 ± 41%, and the increase did not differ from the triiodothyronine-induced increase observed in untreated cells. Addition of DBcGMP also significantly reduced the basal RSR (Table 1), and treatment with both 100 pM triiodothyronine and DBcGMP significantly increased RSR by 253 ± 2%. However, the increase was significantly less than the triiodothyronine-induced increase measured in untreated cells.

Table 1.

Effects of 100 pM T3 on RSR, renin content, and renin mRNA levels in untreated JG cells and cells treated with A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP

| Untreated | A-23187 (1 μM) |

SQ-22536 (100 μM) |

DBcGMP (100 μM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSR, pg of ANG I · h−1 · min−1 · million cells−1 | ||||

| In the absence of T3 | 178 ± 22 | 68 ± 4* | 62 ± 6* | 70 ± 2* |

| In the presence of T3 | 804 ± 82† | 68 ± 4 | 270 ± 4† | 248 ± 4† |

| Renin content, ng of ANG I · h−1 · million cells−1 | ||||

| In the absence of T3 | 35 ± 4 | 17 ± 1* | 15 ± 1* | 30 ± 1 |

| In the presence of T3 | 105 ± 10† | 47 ± 2† | 54 ± 3† | 91 ± 10† |

| Renin mRNA level, ratio of GAPDH mRNA level, % | ||||

| In the absence of T3 | 59 ± 13 | 24 ± 1* | 23 ± 1* | 58 ± 6 |

| In the presence of T3 | 229 ± 13† | 76 ± 7† | 71 ± 10† | 208 ± 20† |

Data are means ± SE of 5 primary cultures. RSR, T3, triiodothyronine; RSR, renin secretion rate; JG, juxtaglomerular; ANG I, angiotensin I; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. RSR samples were taken 6 h after treatment. Samples for renin content and renin mRNA level were collected 24 h after treatment.

P < 0.05 vs. untreated cells in the absence of T3.

P < 0.05 for the presence vs. absence of T3.

Incubation for 6 h with 100 pM triiodothyronine in untreated cells and cells treated with A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP brought about a slight but significant decrease in the viable cell count by 9 ± 2, 15 ± 5, 12 ± 3, and 11 ± 3%, respectively (n = 3 cultures in each group), compared with that measured in freshly isolated cells; however, the decreases were similar across the four treatment groups.

Effects of A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP on triiodothyronine-stimulated increases in renin content

The effect of a 24-h incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine combined with A-23187, SQ-22536, and DB-cGMP on the renin content of JG cells is shown in Table 1. After a 24-h incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine, the renin content in JG cells had increased significantly by 233 ± 7%. Incubation with A-23187 significantly reduced the basal renin content compared with that measured in untreated cells, as shown in Table 1, and incubation with both A-23187 and triiodothyronine significantly elevated the renin content by 175 ± 18%. However, the elevation was significantly less than the increase with triiodothyronine alone. The basal renin content of the SQ-22536-treated cells was significantly lower than the content of the untreated cells (Table 1). Renin content was significantly increased by 261 ± 34% when treated with both SQ-22536 and triiodothyronine. This increase was similar to the triiodothyronine-induced increase observed in untreated cells. The basal renin content of cells treated with DBcGMP was similar to the content of the untreated cells (Table 1). The renin content of cells incubated with both DBcGMP and triiodothyronine increased by 206 ± 25% but did not differ from the renin content of cells incubated with triiodothyronine alone.

The viable cell count of the untreated cells and cells treated with A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP decreased by 15 ± 3, 19 ± 5, 17 ± 4, and 17 ± 5%, respectively (n = 4 cultures in each group), after 24-h incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine, compared with the viable cell count measured in freshly isolated cells, but no differences in decrease among the four treatment groups were significant.

Effects of A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP on triiodothyronine stimulation of renin mRNA expression

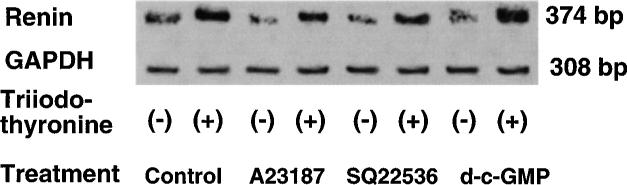

As demonstrated in Fig. 5, incubation with A-23187, SQ-22536, or DBcGMP did not affect the GAPDH mRNA levels of JG cells. The contributions of A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP to the effect of a 24-h incubation with 100 pM triiodothyronine on renin mRNA levels were investigated (Table 1). Incubation with triiodothyronine increased the renin mRNA levels of the untreated cells by 308 ± 64%. Incubation with A-23187 and SQ-22536 for 24 h significantly reduced the basal renin mRNA levels, as shown in Table 1. However, incubation with triiodothyronine still increased the renin mRNA levels of JG cells treated with A-23187 and SQ-22536 by 213 ± 38 and 205 ± 43%, respectively. These increases were similar to the increase observed in untreated cells. When JG cells treated with DBcGMP were incubated with triiodothyronine, their renin mRNA levels increased by 269 ± 64%. Treatment with DBcGMP did not alter basal renin mRNA levels (Table 1) or the increases in renin mRNA levels induced by triiodothyronine, compared with the levels measured in untreated cells.

Fig. 5.

Representative electrophoretogram showing effect of A-23187, SQ-22536, and DBcGMP on renin and GAPDH mRNA levels in JG cells incubated in absence and presence of 100 pM triiodothyronine for 24 h.

DISCUSSION

The circulating renin of rats and humans is primarily synthesized and secreted by JG cells. Although thyroid hormone is known to have numerous actions in vivo, it remains unclear how it influences renin synthesis and secretion by JG cells. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of thyroid hormone on renin secretion, renin content, and renin mRNA levels in JG cells. The results indicate that thyroid hormone has no effect on renin secretion immediately after its application, but that it dose dependently stimulates renin secretion within 6 h and increases expression of the renin gene and its product within 24 h. Although thyroid hormone may exert some acute extranuclear actions, most of the physiological effects of thyroid hormone are mediated by its nuclear receptors, which require a relatively longer time to be manifested (14). The time course of the observed effects of thyroid hormone on renin secretion, content, and mRNA levels strongly implied that the nuclear receptors are involved.

Studies have demonstrated that the nuclear receptors for thyroid hormone can also influence the gene expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (2, 9, 27, 28) and thus alter intracellular concentrations of Ca2+. Because cytosolic Ca2+ is an inhibitory signal for renin synthesis and secretion (8), thyroid hormone may stimulate renin synthesis and secretion through modulation of the gene expression of substances that influence intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. These findings led to further studies that were performed to investigate the contribution of cytosolic Ca2+ to the triiodothyronine-induced stimulation of renin secretion, renin content, and renin mRNA levels in JG cells. The intracellular Ca2+ concentration of cultured JG cells was increased by incubation with the calcium ionophore A-23187. Consistent with previous findings (4, 5, 8), RSR, renin content, and renin mRNA levels were significantly lower in A-23187-treated cells than in untreated cells (Table 1). Simultaneous incubation of triiodothyronine with A-23187 completely inhibited the stimulation of renin secretion caused by incubation with triiodothyronine alone. Therefore, the effect of triiodothyronine on renin secretion is not compatible with elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. In contrast, A-23187 attenuated the response of the renin content of JG cells to triiodothyronine and had no effect on the increase in renin mRNA levels of JG cells in response to triiodothyronine. Thus the intracellular Ca2+ concentration may play an important role in thyroid hormone-induced stimulation of renin secretion by JG cells and renin content of JG cells, even though renin gene expression in response to thyroid hormone is independent of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. However, the results of the present study do not provide any clues to the Ca2+-dependent intracellular mechanism responsible for the thyroid hormone-induced stimulation of renin secretion and renin content since A-23187 increases Ca2+ influx without involving receptor-mediated systems (26) and thus exerts a nonspecific increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations.

In addition to Ca2+, cytosolic cAMP and cGMP are major regulatory factors in the control of renin secretion by JG cells and have stimulatory and inhibitory effects, respectively, on renin secretion (8). cAMP also stimulates renin mRNA levels in JG cells (5). In a pituitary cell line transfected with the 5′-flanking DNA of the human renin gene, thyroid hormone modulates renin gene expression through decreasing Pit-1 levels, which are suggested to contribute to the cAMP-induced upregulation of the renin gene (7, 31). Therefore, the nuclear actions of thyroid hormone on renin regulation may depend on intracellular concentrations of cyclic nucleotides. We also examined the renin secretion, content, and mRNA responses of JG cells to triiodothyronine under conditions of altered intracellular concentrations of cAMP and cGMP. Inhibition of cAMP synthesis with SQ-22536 decreased RSR, renin content, and renin mRNA levels in JG cells (Table 1). Addition of cGMP decreased RSR but did not influence renin content or renin mRNA levels (Table 1). These results confirmed previous findings (4, 5, 8). Although SQ-22536 did not affect the response of RSR, renin content, and renin mRNA levels to triiodothyronine, addition of cGMP attenuated the stimulation of renin secretion in response to triiodothyronine without any effect on the renin content or renin mRNA level responses to triiodothyronine. It is therefore possible that cytosolic cGMP also contributes to the mechanism responsible for the thyroid hormone-induced stimulation of renin secretion by JG cells. However, studies demonstrate that cGMP inhibits phosphatidylinositol hydrolysis (11, 21, 25), Ca2+ influx from extracellular fluid (32), and/or Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores (15, 32). In the present study, administration of DBcGMP may modulate the intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and thereby attenuate the Ca2+-dependent effect of thyroid hormone on renin secretion.

There is a strong homology between the 5′-flanking DNA of the mouse submandibular gland renin gene and thyroid hormone-responsive elements that are recognized in the rat α-myosin heavy-chain gene and the human growth hormone gene (16). It is therefore conceivable that thyroid hormone may act directly on thyroid-hormone-responsive elements of the renin gene in rat JG cells and modulate the promoter activity of the renin gene. The results of this study suggest that thyroid hormone enhances renin gene expression without involving increases in cytosolic Ca2+ and cGMP or a decrease in cAMP in JG cells. However, as other investigators have indicated (7, 31), the mechanism responsible for thyroid hormone-induced renin gene expression seems to be highly complex, and further studies will be required for clarification.

Differences in time-dependent responses to triiodothyronine were observed among RSR, renin content, and renin mRNA levels. Triiodothyronine enhanced the maximum increase in RSR observed at 6 h after the start of incubation, when its effects on renin content and mRNA levels were just beginning. Therefore, secretion may stimulate the subsequent increase in renin content and mRNA levels. However, A-23187 completely inhibited the increase in renin secretion at6hof incubation with thyroid hormone, and yet thyroid hormone increased renin mRNA levels at 24 h in the presence of A-23187. This suggests that thyroid hormone stimulates renin mRNA expression independent of its effect on renin secretion.

The steps we took to avoid inactive prorenin conversion and cryoactivation of prorenin mean that the RSR and renin content results of this study originated from active renin. However, kidney is also a primary source of circulating inactive prorenin in rats (17). Therefore, thyroid hormone may modulate secretion and conversion of prorenin and thus influence renin secretion indirectly, although the effects of thyroid hormone on prorenin release and prorenin content were not determined in the present study.

The calcium ionophore, A-23187, completely inhibited the increase in RSR and did not influence the increase in renin mRNA levels in response to triiodothyronine, whereas the thyroid hormone-induced increase in renin content of JG cells was attenuated by A-23187. This unexpected finding may be due to Ca2+ modulation of prorenin processing. Studies suggest that excess Ca2+ decreases the activity of the KCl/H exchanger (30), which transports K and Cl out for H into JG cells (19) and thus leads to intracellular alkaline conditions. Because processing of prorenin to renin requires extremely acidic conditions (18), in the presence of A-23187 prorenin processing may be suppressed; thus thyroid hormone would fail to increase renin content of JG cells despite the increase in renin mRNA levels. Alternatively, A-23187 may inhibit dynamic prorenin synthesis at the level of the translation of renin mRNA, which was not determined in the present study, although we did determine the steady-state renin mRNA levels.

We previously demonstrated that plasma renin activity, renal renin content, and renal levels of renin mRNA depend on thyroid function in in vivo denervated rats (20). Taken together with the results of the present in vitro study, the increased plasma renin activity observed in hyperthyroidism may, in part, result from direct stimulation by thyroid hormone of renin secretion, content, and mRNA levels in JG cells.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated stimulation of renin secretion, content, and mRNA levels by thyroid hormone in JG cells. Triiodothyronine did not have an immediate effect on renin secretion, but addition of triiodothyronine dose and time dependently stimulated renin secretion, content, and mRNA levels in JG cells. The effect of triiodothyronine on renin secretion by JG cells was completely inhibited by A-23187 and attenuated by DBcGMP. Cytosolic Ca2+ and cGMP may contribute to the stimulatory response of renin secretion to triiodothyronine. A-23187 attenuated the effect of triiodothyronine on the renin content of JG cells, suggesting that cytosolic Ca2+ also participates in the triiodothyronine-induced increase in renin content. The effect of triiodothyronine on renin mRNA levels was unaffected by A-23187, SQ-22536, or DBcGMP. The nuclear receptor for thyroid hormone can stimulate the renin gene independently of the effects of cytosolic Ca2+ and cyclic nucleotides on gene expression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Edward W. Inscho, Ph.D., for helpful comments and discussion.

This work was supported in part by research grants from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation (Tokyo, Japan) and from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan (No. 09770500).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson PW, Do YS, Schambelan M, Horton R, Boger RS, Luther RR, Hsueh WA. Effects of renin inhibition in systemic hypertension. Am. J. Cardiol. 1990;66:1342–1347. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkman C, Ojamaa K, Klein I. Time course of the in vivo effects of thyroid hormone on cardiac gene expression. Endocrinology. 1992;130:2001–2006. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.4.1312435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M, Schnermann J, Smart AM, Brosius FC, Killen PD, Briggs JP. Cyclic AMP selectively increases renin mRNA stability in cultured juxtaglomerular granular cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:24138–24144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Della-Bruna R, Kurtz A, Corvol P, Pinet F. Renin mRNA quantification using polymerase chain reaction in cultured juxtaglomerular cells. Circ. Res. 1993;73:639–648. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Della-Bruna R, Pinet F, Corvol P, Kurtz A. Opposite regulation of renin gene expression by cyclic AMP and calcium in isolated mouse juxtaglomerular cells. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1266–1273. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dzau VJ, Herrmann HC. Hormonal control of angiotensinogen production. Life Sci. 1982;30:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert MT, Sun J, Yan Y, Oddoux C, Lazarus A, Tansey WP, Lavin TN, Catanzaro DF. Renin gene promoter activity in GC cells is regulated by cAMP and thyroid hormone through Pit-1-dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:28049–28054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hackenthal E, Paul M, Ganten D, Taugner R. Morphology, physiology, and molecular biology of renin secretion. Physiol. Rev. 1990;70:1067–1116. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartong R, Wang N, Kurokawa R, Lazar MA, Glass CK, Apriletti JW, Dillmann WH. Delineation of three different thyroid hormone-response elements in promoter of rat sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ATPase gene. Demonstration that retinoid X receptor binds 5′ to thyroid hormone receptor in response element 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:13021–13029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauger-Klevene JH, Brown H, Zavaleta J. Plasma renin activity in hyper- and hypothyroidism: effect of adrenergic blocking agents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1972;34:625–629. doi: 10.1210/jcem-34-4-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirata M, Kohse KP, Chang C, Tkebe T, Murad F. Mechanisms of cyclic GMP inhibition of inositol phosphate formation in rat aorta segments and cultured bovine aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1268–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichihara A, Suzuki H, Murakami M, Naitoh M, Matsumoto A, Saruta T. Interactions between angiotensin II and norepinephrine on renin release by juxtaglomerular cells. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 1995;133:569–577. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1330569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichihara A, Suzuki H, Saruta T. Effects of magnesium on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in human subjects. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1993;122:432–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jameson JL, DeGroot LJ. Mechanism of thyroid hormone action. In: DeGroot LJ, Besser M, Burger HG, Jameson JL, Loriaux DL, Marshall JC, Odell WD, Potts JT Jr., Rubenstein AH, editors. Endocrinology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1995. pp. 583–601. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannan MS, Prakash YS, Johnson DE, Sieck GC. Nitric oxide inhibits calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum of porcine tracheal smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L1–L7. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.1.L1. (Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 16)

- 16.Karen P, Morris BJ. Stimulation by thyroid hormone of renin mRNA in mouse submandibular gland. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:E290–E293. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.251.3.E290. (Endocrinol. Metab. 14)

- 17.Kim S, Hosoi M, Nakajima K, Yamamoto K. Immuno-logical evidence that kidney is primary source of circulating inactive prorenin in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:E526–E536. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.4.E526. (Endocrinol. Metab. 23)

- 18.King JA, Fray JCS. Hydrogen and potassium regulation of (pro)renin processing and secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:F1–F12. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.267.1.F1. (Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 36)

- 19.King JA, Lush DJ, Fray JCS. Regulation of renin processing and secretion: chemiosmotic control and novel secre-tory pathway. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:C305–C320. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.2.C305. (Cell Physiol. 34)

- 20.Kobori H, Ichihara A, Suzuki H, Miyashita Y, Hayashi M, Saruta T. Thyroid hormone stimulates renin synthesis in rats without involving the sympathetic nervous system. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:E227–E232. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.2.E227. (Endocrinol. Metab. 35)

- 21.Lang D, Lewis MJ. Endothelium-derived relaxing factor inhibits the formation of inositol trisphosphate by rabbit aorta. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1989;411:45–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchant C, Brown L, Sernia C. Renin-angiotensin system in thyroid dysfunction in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1993;22:449–455. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199309000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paul M, Ganten D. The molecular basis of cardiovascular hypertrophy: the role of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1992;19(Suppl 5):S51–S58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polikar R, Kennedy B, Ziegler M, O'Connor DT, Smith J, Nicod P. Plasma norepinephrine kinetics, dopa-mine-beta-hydroxylase, and chromogranin-A, in hypothyroid patients before and following replacement therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1990;70:277–281. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-1-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapaport R. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibition of contraction may be mediated through inhibition of phosphoinosi-tide hydrolysis in rat aorta. Circ. Res. 1986;18:407–410. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed PW, Lardy HA. A23187: a divalent cation ionophore. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:6970–6977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohrer D, Dillmann WH. Thyroid hormone markedly increases the mRNA coding for sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ATPase in the rat heart. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:6941–6944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohrer DK, Hartong R, Dillmann WH. Influence of thyroid hormone and retinoic acid on slow sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ATPase and myosin heavy chain gene expression in cardiac myocytes; delineation of cis-active DNA elements that confer responsiveness to thyroid hormone but not to retinoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:8638–8646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sealey JE. Plasma renin activity and plasma prorenin assays. Clin. Chem. 1991;37:1811–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sigmon DH, Fray JCS. Chemiosmotic control of renin release from isolated renin granules of rat kidneys. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 1991;436:237–256. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun J, Oddoux C, Lazarus A, Gilbert MT, Catanzaro DF. Promoter activity of human renin 5′-flanking DNA sequences is activated by the pituitary-specific transcription factor Pit-1. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1505–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan X-J, Bright RT, Aldinger AM, Rubin LJ. Nitric oxide inhibits serotonin-induced calcium release in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L44–L50. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.1.L44. (Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 16)